Abstract

Context:

Decisions in the organization of safe and effective rural maternity care are complex, difficult, value laden and fraught with uncertainty, and must often be based on imperfect information. Decision analysis offers tools for addressing these complexities in order to help decision-makers determine the best use of resources and to appreciate the downstream effects of their decisions.

Objective:

To develop a maternity care decision-making tool for the British Columbia Northern Health Authority (NH) for use in low birth volume settings.

Design:

Based on interviews with community members, providers, recipients and decision-makers, and employing a formal decision analysis approach, we sought to clarify the influences affecting rural maternity care and develop a process to generate a set of value-focused objectives for use in designing and evaluating rural maternity care alternatives.

Setting:

Four low-volume communities with variable resources (with and without on-site births, with or without caesarean section capability) were chosen.

Participants: Physicians (20), nurses (18), midwives and maternity support service providers (4), local business leaders, economic development officials and elected officials (12), First Nations (women [pregnant and non-pregnant], chiefs and band members) (40), social workers (3), pregnant women (2) and NH decision-makers/administrators (17).

Results:

We developed a Decision Support Manual to assist with assessing community needs and values, context for decision-making, capacity of the health authority or healthcare providers, identification of key objectives for decision-making, developing alternatives for care, and a process for making trade-offs and balancing multiple objectives. The manual was deemed an effective tool for the purpose by the client, NH.

Conclusions:

Beyond assisting the decision-making process itself, the methodology provides a transparent communication tool to assist in making difficult decisions. While the manual was specifically intended to deal with rural maternity issues, the NH decision-makers feel the method can be easily adapted to assist decision-making in other contexts in medicine where there are conflicting objectives, values and opinions. Decisions on the location of new facilities or infrastructure, or enhancing or altering services such as surgical or palliative care, would be examples of complex decisions that might benefit from this methodology.

Abstract

Contexte:

Les décisions touchant l'organisation de soins de maternité sécuritaires et efficaces en milieu rural sont complexes, difficiles, empreintes de valeurs et marquées d'incertitudes; de plus, elles doivent souvent se fonder sur une information incomplète. L'analyse décisionnelle offre des outils pour faire face à cette complexité, afin d'aider les décideurs à déterminer le meilleur usage des ressources et à considérer les effets découlant de leurs décisions.

Objectif:

Mettre au point un outil d'appui à la prise de décisions pour les soins de maternité dans la Région sanitaire du nord de la Colombie-Britannique (British Columbia Northern Health Authority), pour les collectivités à faible volume de naissances.

Conception:

À l'aide d'entrevues avec des membres de la collectivité, des prestataires de soins, des bénéficiaires et des décideurs – ainsi qu'à l'aide d'une méthode d'analyse des décisions officielles – nous avons tenté de clarifier les influences qui entrent en jeu dans les soins de maternité en milieu rural et de mettre au point un processus visant à dégager des objectifs centrés sur les valeurs pour la conception et l'évaluation des choix qui s'offrent pour les soins de maternité en milieu rural.

Collectivités:

Nous avons choisi quatre collectivités à faible volume de naissances et dotées de ressources variables (avec ou sans naissances sur les lieux, avec ou sans capacité pour les césariennes).

Participants : Médecins (20), infirmières (18), sages-femmes et fournisseurs de services de soutien en maternité (4), entrepreneurs locaux, responsables du développement économique et élus (12), Autochtones (femmes [enceintes ou non], chefs et membres de bande) (40), travailleurs sociaux (3), femmes enceintes (2) et décideurs ou administrateurs de la Région sanitaire (17).

Résultats:

Nous avons mis au point un manuel d'appui aux décisions afin de permettre l'évaluation des besoins et des valeurs de la collectivité, définir le contexte de prise de décisions, évaluer la capacité de la région sanitaire ou des prestataires de services de santé, déterminer des objectifs clés pour la prise de décisions, mettre en place d'autres choix pour les services de soins et mettre au point un processus pour les compromis et pour équilibrer les multiples objectifs. Le manuel a été jugé un outil efficace pour les besoins du client, soit la Région sanitaire.

Conclusions:

Au-delà de l'appui à la prise de décisions, la méthodologie offre un outil de communication transparent qui facilite la prise de décisions difficiles. Bien que le manuel ait été conçu spécialement pour les enjeux liés à la maternité en milieu rural, les décideurs de la Région sanitaire estiment que la méthode peut facilement s'adapter à d'autres contextes où il y a des objectifs conflictuels ainsi que des enjeux liés aux valeurs et aux opinions. Les décisions liées à l'emplacement de nouvelles installations ou infrastructures, ou liées à l'amélioration de services tels que la chirurgie ou les soins palliatifs, constituent des exemples de décisions complexes qui peuvent tirer avantage de cette méthodologie.

This paper provides a background and summary of the work associated with the development of an evidence-based manual and toolkit to assist decision-makers in making optimal decisions for the provision of maternity care in low birth volume settings in rural northern British Columbia (Hearns et al. 2008). The full manual can be downloaded on request as a PDF file from the authors.

Across much of rural British Columbia, decision-makers are faced with very difficult choices when addressing issues of rural maternity care. In the province, between 1997 and 2005, roughly a quarter of facilities serving over 500 births per year were closed. Such healthcare decisions have profound impacts in rural areas, and improving and aiding in the quality of these decisions is therefore of great consequence and associated with high impact. When maternity services close, women and families must travel to receive care. As a result, they lose personal and family supports and often incur significant financial costs. First Nations communities lose important cultural and community context. Moreover, despite ultimately receiving competent care, when women travel large distances to deliver, the rate of premature births and neonatal asphyxia increases, as do other maternal and newborn complications (Samuels et al. 1991; Black and Fyfe 1984; Chamberlain and Barclay 2000; Frankenberg and Thomas 2001; Grzybowski et al. 1991; Nesbitt et al. 1997).

It is not clear why prematurity rates rise when women need to leave their communities to receive care, but we presume that it relates to increased stress and reduced family and other supports in the distant location where they eventually give birth. While outcomes for premature infants are improved by centralization of services, outcomes for babies of average size/weight are not (Reynolds and Klein 2000; Larimore and Davis 1995; Nesbitt et al. 1990). Although the effects of centralization in some settings may not have detrimental impacts on the health of women and their babies, we suggest that this change in the way in which maternity care is provided to small rural communities has wide-ranging effects for community sustainability. Ireland and colleagues (2007) have noted that centralization “has created particular difficulties, such as reduced patient choice, quality of care, safety and sustainability of maternity services, lack of trained staff, and professional development.”

One consequence of reducing maternity care includes reduced availability of physicians, nurses and other maternity support staff in the affected site and community, leading to further difficulties in recruitment and retention. The loss of medical facilities also affects economic capital, as businesses find it difficult to recruit employees, thereby reducing community economic viability (Klein et al. 2002). This relationship between healthcare and sustainable communities is seldom given adequate consideration when making decisions about maternity care services.

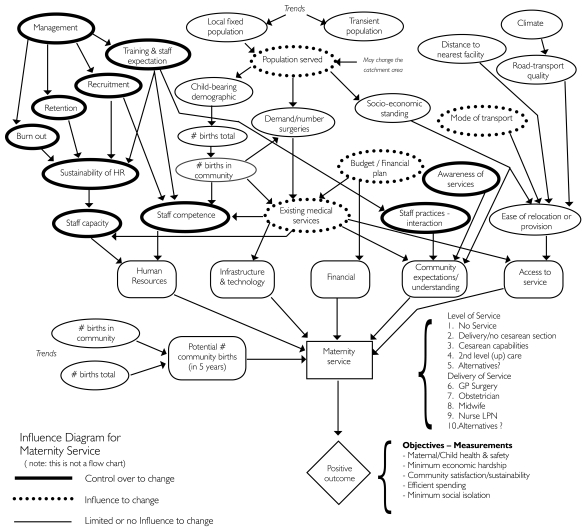

In balancing fiscal constraints and limited resources with community interests and maintaining health standards, the decision-maker may be faced with a large number of competing and often conflicting forces. Figure 1 shows an influence diagram of the issues affecting the choice of maternity services. The diagram was constructed from a series of interviews with decision-makers in four different northern rural communities in British Columbia and in the central offices of Northern Health (NH). It is not meant to be a comprehensive analysis of all potential situations, but rather a general snapshot of the complexity of major influences. While the decision-makers have no control over the climate or the socio-economic standing of the clients served, they may, however, have some influence over budgets or financial planning, and generally have a good deal of control over such factors as management of human resources and community awareness of services. It is in the areas of “greatest control” that the most effective actions are likely to be found.

FIGURE 1.

Issues affecting decision-making for rural maternity services

Usually, the decision-making process focuses on administration, fiscal and safety issues. Solutions often follow previously made decisions, with little debate or dialogue around options (Hammond et al. 1999). In bureaucracies, this approach is less time-consuming, simpler and safer. Involving local communities is often perceived to be time-consuming and awkward. In Alberta, during a survey of key decision-makers in rural health authorities, the respondents indicated that while the majority of them relied on utilization data and information, few looked to public input to help set priorities for service delivery. Yet, they overwhelmingly believed that more frequent dialogue with the public was required (Mitton and Donaldson 2002). In response to findings that local communities were not being adequately consulted, numerous commissions and reports in Canada in the late 1980s and early 1990s strongly advocated for increased citizen participation in healthcare1 (Charles and DeMaio 1993). Since then the major question is not whether, but rather, how best to engage local communities and the public in complex deliberations associated with healthcare issues (Abelson et al. 2003; Litva et al. 2002). In general, people have difficulty making complex decisions (McDaniels et al. 1999). This is particularly true with respect to health, where perceptions can greatly influence choice (Litva et al. 2002). Moreover, the method for public engagement must meet the local community's capacity to participate (Abelson 2001). This point is particularly important in rural British Columbia, where there are varying levels of socio-economic standing between and among communities.

We propose that through a structured process of identifying and evaluating alternatives, creative and defensible choices can be made in difficult decisional contexts that accommodate different capacities within communities. If these choices are done well, the stakeholders, communities and healthcare workers are more likely to be sympathetic, or at least understanding of decisions made. Moreover, the process helps ensure that creative alternatives are produced and evaluated in a transparent and unbiased manner. Good solutions have their foundation in effective and creative alternatives from which to choose. Most importantly, even a reduction in services does not mean that the decision-makers can avoid caring for populations in their area of responsibility, but it does mean that services will have to be organized differently.

The decision-support framework developed during this project was created in order to aid the regional health authority, Northern Health, in making optimal decisions about how to maintain low-volume maternity care services. Understanding that both time and resources are limited, these processes and guides are not meant to be onerous or complicated. Rather, they are intended to ensure that the interests of those affected by the decisions are adequately and efficiently taken into account, and that the final results of the process may be communicated in an effective manner. The methodology can be adapted to fit the needs of the decision-makers in terms of scope, timing and budget.

Methodology

NH serves a population of 300,000 people thinly distributed across a large geographic area encompassing two-thirds of British Columbia. Most communities are small and rural or remote, with significant First Nations populations. To reflect the diversity of situations, the communities of Quesnel, Vanderhoof, Fraser Lake, Fort St. James and surrounding First Nations were selected for assessment based on number of births, variety and level of services provided, socio-economic conditions and ethnic diversity. The case studies that provided the basis for the model that we present are subject to the main driving forces affecting many rural areas, such as declining populations and birth rates, weakening economies, difficulties in attracting and maintaining healthcare workers, pressure to centralize services and cultural diversity. The lower birth rates are also found in First Nations communities, but they continue to have the highest birth rates in the province.

Between autumn 2005 and winter 2007, established qualitative and decision-analysis techniques were applied to assess the four community case studies. The complexity of providing local maternity care was detailed through 51 interviews and 12 focus groups with key stakeholder groups: healthcare administrators, women, First Nations, community leaders, elected officials, business leaders, and physicians, nurses and other care providers (e.g., doulas, community health workers).2 Based on an analysis of the influences affecting decisions related to rural maternity care, the needs of administrators and decision-makers were clarified and became the framework for developing decision-making support tools. A process, founded on value-focused decision-analysis theory (Keeney 1992; Kirkwood 1997; Clemen and Reilly 2000), was developed to help identify key objectives and to generate and evaluate strategic alternatives. The process and guide were refined and field-tested in an additional community under stress, in parallel with a traditional process of decision-making. The result was that many of the recommendations emerging from the field test were incorporated into the report and the manual itself, from the traditional process.

The decision-making framework

The decision-making framework helps to identify and evaluate creative alternatives and to make defensible and easily communicated choices in complex situations. It aims to develop insight and understanding among decision-makers regarding how well their objectives can be achieved by different courses of action (or alternatives), the most likely core trade-offs and the relative risk associated with each. For example, some actions may be seen as “must-do,” with relatively little risk associated with their implementation. They may be inexpensive, easy to accomplish administratively and in a short period of time, and have a high impact on the objectives at hand. An example might be the creation and distribution of information pamphlets for building community awareness. Others may have greater associated risks, such as depending upon a regional community outreach program to educate your local community. Linking actions that depend upon the success of previous actions also compounds the risks associated with a particular strategy. These and other considerations are discussed in greater detail in the manual.

The process is specifically designed to engage various stakeholders including technical experts, community members, First Nations, caregivers and administrators, among others. The methodology assumes that the ultimate decision-making power rests in the hands of the decision-makers. It is not meant to be a drawn-out or complicated process, though the required time and resources will depend upon the context of the decision to be made.

The process has been modelled on value-focused decision analysis and is based on several fundamental principles. It is a value-based process that clarifies what matters to those principally affected by the decision. “What matters” is developed into evaluation criteria (objectives) as a means of choosing between various options for action. The process is informed through insight and understanding based on facts derived from interviews, expert judgments, research or statistics and other available perspectives. The process is collaborative and transparent, focused on mutual learning about objectives and alternatives, and what is important to various stakeholders. It is conducted through a structured and defined series of steps to ensure understanding at each stage and understanding of how decisions have ultimately been made. The structure guarantees that facts and values are used appropriately and in an easily communicated way. Finally, the process is adaptive and designed to be reviewed, modified and updated in an iterative fashion. Clearly, the location of a new facility does not lend itself to being “modified” by changing its location, but it can be modified through other means such as a change in its vocation or range of services provided.

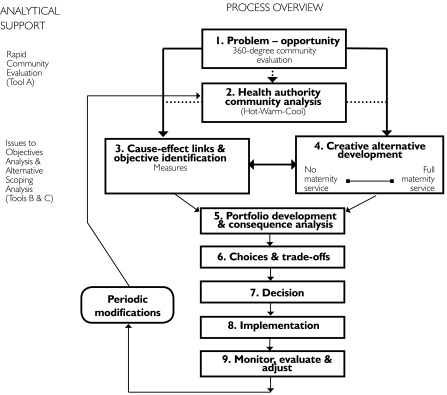

The basic steps of the process are laid out in Figure 2, which shows the decision tools that have been developed for various stages of the process.

FIGURE 2.

Decision tools

Public policy decisions are often taken in a reactive atmosphere where the need for action may appear to outweigh the need to take a step back and clarify the complexity of the decision and its context (Clemen and Reilly 2000; Beierle and Cayford 2002). The need for clarity and the choice of organized methods for dealing with public perceptions can be difficult, particularly in the area of public health policy (Anand 2002). Consequently, when it is feasible to do so, it is generally simpler to do what has previously been done, often maintaining the status quo, without going through the route of determining whether it really is the best course of action in the specific context. Through the course of our research and interviews, it was evident that prompted by an undesirable situation, such as stress among nurses on a maternity ward, the desire for a quick solution overwhelmed other potentially more effective solutions. In such a situation, the option put forward may have been to increase the number of nurses on a maternity ward. This is what had been done before; it was simple (provided that nurses were available) and principally required money, as opposed to genuine institutional change. But a rapid decision may or may not address the underlying issue. Taking the issue as an opportunity to effect change, the real decisional context is how to improve maternity services, where hiring more nurses may be only one course of action. Other potential actions may include altering the practice of physicians, reducing dependence on certain interventions, developing greater community awareness of issues related to childbirth, hiring local community support staff for administrative tasks to free up nursing time, and better planning of schedules, among others. Long-term planning might reveal the need for increased cross-over nurses and training, among other possibilities. The combined effect of several alternatives, or a new strategy, may mitigate the need for simply “more nurses.”

Methods

1. Problem – opportunity

Approaching a problem provides an opportunity to review and assess the issue from a wider perspective. An appropriate understanding of the issues and values is key to providing a caregiving service that considers the views of all stakeholders. This is called a 360-degree community evaluation. It includes local communities, First Nations, caregivers and administrators, among others. The survey should involve interviews or focus groups or other appropriate means of soliciting input. It does not have to be a laborious process, but it is important to let those engaged understand how their information will be used.

2. Health authority community analysis

Information gained must be analyzed, and the decisional context reviewed to ensure that the appropriate discussions and deliberations are carried out. Areas of major concern should be identified. These could be either specific locations or areas of management, such as lack of infrastructure or relations with the community. Revisiting some key interviews may be necessary.

3. Cause–effect links and objective identification

It is very important that clear, concise objectives and evaluation criteria are developed that reflect the values that really matter. These include criteria that address economic, social, cultural and safety considerations that may be affected by the management alternatives under consideration. A cause–effects linkage tool helps define the actual objective versus a mere “issue” or “concern.”

4. Creative alternative development

This step involves developing a suite or range of alternatives to be considered for objective evaluation. It is important that they not be prejudged, as this is one of the keys to transparency and meaningful stakeholder input. Alternatives that clearly do not meet the objectives will likely be discarded in step 5.

5. Portfolio development and consequence analysis

This step involves technical analysis to address how the alternatives may achieve the identified goals. It may involve available information, estimates and judgments from technical experts and local holders of knowledge. In general, the findings are summarized in a consequence table tool to explicitly show relative effects of different actions. Suites of actions, termed portfolios, can be developed for evaluation against one another. In this way, actions with little impact will fall away, while those with greater impact will be expanded and further developed.

6. Choices and trade-offs

This step is the basis for balancing the different values incorporated in complex situations such as deciding about the delivery of maternity care services. Although win–win solutions are always sought, difficult choices will usually result in having to emphasize certain objectives and issues over others. While tools and consequence tables will help inform the discussion, they do not make the choices. What is desired is an acceptable balance, across the objectives, such that stakeholders can accept the decisions taken – even difficult ones. If time and resources permit, it is useful to include all key stakeholders in this process to ensure better buy-in of a final strategy.

7. Decision

The decision will ultimately be made by those responsible.

8. Implementation

It is important to consider implementation issues up front as part of the community survey. Ideally when this step is reached, the selected decision can be implemented – because such considerations as finance, political will and other factors have already been addressed in choosing the strategy. It is therefore important to address all these components early on as part of the initial objectives or evaluation criteria.

9. Monitor, evaluate and adjust

Funds should be made available for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the activities chosen.

Conclusions

Decisions regarding the provision of services for rural maternity care are complex and often difficult. As with many healthcare decisions, they tend to be value laden and sensitive. For good decisions to be made, there is a need to undertake processes that address the underlying stakeholder interests in a transparent and defensible way. While a desire by many decision-makers to be more inclusive and transparent must be acknowledged, this desire is also frequently associated with decision-makers' concerns that the process will become too complex and onerous, thereby consuming time and more resources – and exposing the decision-makers to undue community influences. But by focusing on the objectives that matter, in terms of society and local communities as well as care providers and administrators, and through engaging all the key stakeholders, many problems can be avoided.

A structured process has the advantage of addressing complex issues in a systematic manner in order to arrive at defensible and easily communicated decisions. While this manual and toolkit have been designed for decision-making in the provision of rural maternity care, decision-makers in Northern Health feel that it can be adapted to a number of different healthcare situations or applications, especially when conflicting values and objectives are at play in the face of limited resources. This methodology has been applied to the location of emergency response facilities, and could be easily extended to decisions about the location or upgrading of new infrastructure (such as upgrading surgical units) or establishing cancer treatment facilities. The methodology also lends itself to decisions on enhancing existing services, similar to how it has been designed for maternity services. Enhancing palliative care and surgical services would also clearly benefit from such a methodology, particularly in light of the contentious community interaction usually associated with such decisions. Northern Health has already applied the manual or the principles therein to two communities under stress, and it is actively planning to apply the method to other low-volume situations in the North well beyond maternity care.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Vancouver and Michael Smith foundations.

Premier's Commission on Future Health Care for Albertans 1989; Nova Scotia Royal Commission on Health Care 1989; Ontario Health Review Panel 1987; Ontario Ministry of Health 1989; Premier's Council on Health Strategy 1991; Saskatchewan Commission on Directions in Health Care 1990; Saskatchewan Health 1992.

This included the following populations: physicians (20), nurses (18), midwives and other maternity support service providers (e.g., doulas, childbirth educators, breastfeeding counsellors and outreach workers – many in dual or multiple roles) (4), local business leaders and economic development officials, local elected officials (e.g., mayor, city and band councillors) (12), First Nations (women [pregnant and non-pregnant], chiefs and band members) (40), social workers (3), pregnant women and women who have given birth within the past 12 months (2) and 17 decision-makers from Northern Health.

Contributor Information

Glen Hearns, Senior Policy and Decision Analyst, Compass Resource Management, Vancouver, BC.

Michael C. Klein, Senior Scientist Emeritus, Child and Family Research Institute, Professor Emeritus, University of British Columbia, Principal Investigator, Maternity Care Research Group, Vancouver, BC.

William Trousdale, President, EcoPlan International, Associate, Simon Fraser Centre for Sustainable Community Development, Adjunct Professor, UBC School of Community and Regional Planning, Vancouver, BC.

Catherine Ulrich, President and CEO, Northern Health Authority, Prince George, BC.

David Butcher, Vice President Medicine, Northern Health Authority, Prince George, BC.

Christiana Miewald, Anthropologist, Research Associate and Adjunct Professor, Centre for Sustainable Community Development, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC.

Ronald Lindstrom, Consultant, Community Development, Vancouver, BC.

Sahba Eftekhary, Senior Specialist, Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Toronto, ON.

Jessica Rosinski, Department of Political Science, University of British Columbia, Senior Research Analyst, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Vancouver, BC.

Oralia Gómez-Ramírez, Department of Anthropology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Andrea Procyk, School of Community and Regional Planning, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

References

- Abelson J. Understanding the Role of Contextual Influences on Local Health-Care Decision Making: Case Study from Ontario, Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53(6):777–93. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson J., Forest P., Eyles J., Smith P., Martin E., Gauvin F. Deliberations about Deliberative Methods: Issues in the Design and Evaluation of Public Participation Processes. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57(2):239–51. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P. Decision-Making When Science Is Ambiguous. Science. 2002;295(5561):1839. doi: 10.1126/science.1061744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierle T., Cayford J. Democracy in Practice: Public Participation in Environmental Decisions. Washington: DC: RFF Press.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Black D., Fyfe I. The Safety of Obstetric Services in Small Communities in Northern Ontario. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1984;130(5):571–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain M., Barclay K. Psychosocial Costs of Transferring Indigenous Women from Their Community for Birth. 2000;16(2):116–22. doi: 10.1054/midw.1999.0202. Midwifery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles M., DeMaio S. Lay Participation in Health Care Decision-Making: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1993;18(4):881–904. doi: 10.1215/03616878-18-4-881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemen R.T., Reilly T. Making Hard Decisions. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg E., Thomas D. Demography. Women's Health and Pregnancy Outcomes: Do Services Make a Difference? 2001;38(2):253–65. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzybowski S., Cadesky A., Hogg W. Rural Obstetrics: A 5-Year Prospective Study of the Outcomes of All Pregnancies in a Remote Northern Community. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1991;144:987–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J., Keeney R., Raiffa H. Smart Choices: A Practical Guide to Making Better Decisions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hearns G., Trousdale W., Klein M.C., Butcher D., Ulrich C., Miewald C., Eftekhary S. the Maternity Care Research Group. Informed Decision-Making: The Interaction between Sustainable Maternity Care Services and Community Sustainability – A Decision Support Manual. Vancouver: University of British Columbia and the Child and Family Research Institute and Northern Health.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland J., Bryers H., van Teijlingen E., Hundley V., Farmer J., Harris F., Tucker J., Kiger A., Caldow J. Competencies and Skills for Remote and Rural Maternity Care: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(2):105–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney R.L. Cambridgeg. MA: Harvard University Press.; 1992. Value-Focused Thinking: A Path to Creative Decision-Makin. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood C. Strategic Decision-Making: Multiobjective Decision Analysis with Spreadsheets. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury Press.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Klein M., Johnston S., Christilaw J., Carty E. Mothers, Babies and Communities: Centralizing Maternity Care Exposes Mothers and Babies to Complications and Endangers Community Sustainability. Canadian Family Physician. 2002;48:1177–79. (Eng) 1183–85 (Fr). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimore W., Davis A. Relation of Infant Mortality to the Availability of Maternity Care in Rural Florida. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 1995;8(5):392–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litva A., Coast J., Donovan J., Eyles J., Shepard M., Tacchi J., Abelson J., Morgan K. The Public Is Too Subjective: Public Involvement at Different Levels of Health Care Decision-Making. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;54(12):1825–37. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniels T., Gregory R., Fields D. Democratizing Risk Management: Successful Public Involvement in Local Water Management Decisions. Risk Analysis. 1999;19(3):497–510. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton C., Donaldson C. Setting Priorities in Canadian Regional Health Authorities: A Survey of Key Decision Makers. Health Policy. 2002;60(1):39–58. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt T.S., Connell F.A., Hart L.B., Rosenblatt R.A. Access to Obstetric Care in Rural Areas: Effect on Birth Outcomes. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80(7):814–18. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.7.814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt T.S., Larson E.H., Rosenblatt R.A., Hart L.G. Access to Maternity Care in Rural Washington: Its Effect on Neonatal Outcomes and Resource Use. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(1):85–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.L.M., Klein M. Recommendations for a Sustainable Model of Maternity and Newborn Care in Canada. In: Reynolds J.L., Klein M., editors. Proceedings of the Future of Maternity Care in Canada: Crisis or Opportunity? 2000. London, ON, November 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels S., Cunningham J.P., Choi C. The Impact of Hospital Closures on Travel Time to Hospitals. Inquiry. 1991;28(2):194–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]