Abstract

In 1965, Daniel Patrick Moynihan warned that non-marital childbearing and marital dissolution were undermining the progress of African Americans. I argue that what Moynihan identified as a race-specific problem in the 1960s has now become a class-based phenomena as well. Using data from a new birth cohort study, I show that unmarried parents come from much more disadvantaged populations than married parents. I further argue that non-marital childbearing reproduces class and racial disparities through its association with partnership instability and multi-partnered fertility. These processes increase in maternal stress and mental health problems, reduce the quality of mothers’ parenting, reduce paternal investments, and ultimately lead to poor outcomes in children. Finally, by spreading fathers’ contributions across multiple households, partnership instability and multi-partnered fertility undermine the importance of individual fathers’ contributions of time and money which is likely to affect the future marriage expectations of both sons and daughters.

Keywords: Family structure, family instability, poverty, inequality, parenting, child wellbeing

Introduction

In his report on the Negro Family, Daniel Patrick Moynihan (1965) noted that non-marital childbearing was increasing among African Americans and that the root causes of the increase were slavery, urbanization and persistent male unemployment. He further argued that these forces had led to a self reinforcing ‘tangle of pathology,’ consisting of non-marital childbearing, high male unemployment, and welfare dependence, which was undermining the progress of African Americans and contributing to the perpetuation of poverty. In the final paragraph of the report, Moynihan stated hat:

The policy of the United States is to bring the Negro American to full and equal sharing in the responsibilities and rewards of citizenship. To this end, the programs of the Federal government bearing on this objective shall be designed to have the effect, directly or indirectly, of enhancing the stability and resources of the Negro American family. (Moynihan, 1965. p. 48)

Although initially praised by the Black leadership for focusing national attention on a serious problem, the ‘Moynihan Report’ soon become the target of harsh and widespread criticism from liberals (and eventually from the Black leadership) for using words like ‘pathology’ to describe the Black family and for attributing the disadvantages of African Americans to family structure rather than structural factors such as racial discrimination and poverty (Rainwater & Yancey 1967). In contrast, social conservatives praised the report and used it support a ‘culture of poverty’ argument which emphasized values and behaviors rather than poverty as the root cause of intergenerational poverty (Ryan 1976).

In the aftermath of the Moynihan controversy, liberal researchers avoided the topic of family structure, or they wrote only about the positive aspects of the Black family (Stack 1974), until the 1980s when William Julius Wilson reopened the debate. In his book on The Truly Disadvantaged, Wilson (1988) refocused attention on the instability of the African American family and its role in undermining the life chances of Black children. Like Moynihan, Wilson distinguished between a Black middle class which he saw as advancing in terms of socio-economic status and a Black lower class which he saw as losing ground. Unlike Moynihan, however, Wilson argued explicitly that best way to strengthen families was to increase men's employment and earnings.

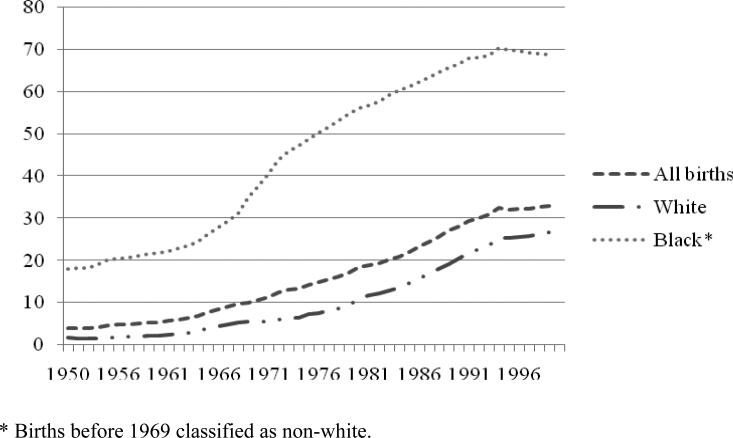

Since the publication of the Moynihan Report, the proportion of African American children born outside marriage has grown dramatically, from 24 percent in 1965 to 69 percent in 2000 (Figure 1). Non-marital childbearing has also increased among other racial and ethnic groups. The proportion of white children born to unmarried parents has grown from 6 percent in 1965 to 24 percent today, and the proportion of Hispanic children has grown from 37 percent in 1990 to 42 percent in 2000.1 And yet after four decades of discussion, the debate over the role of family structure in the reproduction of poverty continues, with the basic positions showing very little change. At one extreme are analysts who argue that non-marital childbearing is a consequence but not a cause of poverty (Coontz & Folbre 2002; at the other extreme are those who argue it is a cause but not a consequence (Murray 1984, Wilson 2002); and in between are those who, like Moynihan and William Julius Wilson, view it as both a cause and a consequence (Massey 2007, Western 2007).2

Figure 1.

Trends in Non-marital Childbearing: 1950-2000

Despite the importance of the topic and the intensity of the debate, empirical data pertaining to unmarried parents and their children has been limited until recently. Although we know something about the characteristics of the women who give birth outside marriage, we know much less about the fathers of these children. And although we know something about the role of economic factors in predicting non-marital childbearing, we have very little data on the role of values and social skills. And finally, although a large body of research exists on the consequences of father absence and single motherhood for parents and children, most of this research is based on divorced families which are likely to differ in important ways from families formed by unmarried parents (McLanahan & Sandefur 1994).

The Fragile Family Study

To learn more among unmarried parents and their children and to address some of the unanswered questions first raised during the debate over the Moynihan report, my colleagues and I began work (in 1998) on the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a longitudinal survey of about 5000 births, including over 3600 births to unmarried parents. The study design called for sampling new parents shortly after the birth of their child and for re-interviewing both mothers and fathers when the focal child was 1, 3 and 5 years old. Child outcomes were assessed at years 3 and 5. To maximize our chances of interviewing fathers as well as mothers, we started at the hospital and sampled new births. In cases where fathers could not be contacted at the hospital, we interviewed them by phone or in person as soon after the birth as possible. Births were sampled in 75 hospitals in 20 large cities throughout the US; when weighted, the data are representative of births in US cities with populations of 200,000 or more people. (Reichman et al. 2001). The study was designed to addresses the following questions:

What are the capabilities of unmarried parents when their child is born, especially fathers?

What is the nature of relationships in fragile families at birth? How do relationships change over time?

How do parents and children fare in fragile families?3

The answers to these questions are important for resolving the debate over the Moynihan Report. For example, the answer to the first question can tell us the extent to which non-marital childbearing is selective of people with different human capital and social skills, and whether these differences are large enough to account for differences in children's outcomes later on. If poverty and low education are the root causes of non-marital childbearing, as some people suggest, we would expect to find substantial differences in the human capital and social skills of married and unmarried parents at the time of their child's birth. If poverty is not a cause, we would expect differences to be small.

The answer to the second question can tell us something about whether families formed by unmarried parents are different from families formed by married parents in terms of parental values and commitment. In addition, by following parents over time, we can compare the stability of marital and non-marital relationships and identify the factors that predict stability. If non-marital unions are less stable than marital unions and if relationship stability is strongly associated with differences in human capital at birth, this finding would support the argument that poverty and economic insecurity cause family instability; alternatively, if instability is associated with differences in commitment and social-emotional skills, this finding would support the argument that the latter are contributing to family instability.

Finally, the answer to the third question can tell us something about whether a non-marital birth leads to differences in parental resources and ultimately to poor child outcomes. If parental resources and child outcomes are no different in married and unmarried-parent families, once socio-economic status at birth is taken into account, this finding would lend support to the argument that non-marital childbearing is a marker but not a cause of future poverty. Alternatively, if family structure is associated with poorer parenting, even after controlling for socio-economic status at birth, or if changes in family structure are associated with changes in parental resources, these findings would lend support to the argument that family structure is a mechanism in the reproduction of poverty. In the next section, I describe what we have learned about these questions during the first five years of the Fragile Families Study, and in the final section I discuss how the findings inform our understanding of the processes underlying intergenerational mobility.

What are unmarried parents’ capabilities, especially fathers?

As noted above, when we began our study in the late 1990s, quite a bit was known about the demographic characteristics of unwed mothers (age, education, parity), thanks to several national surveys that routinely collect information on women's marital and fertility histories. Much less was known about unmarried fathers, however. One reason for the lack of data on fathers was that these men are often omitted from national and local surveys either because they are not identified by standard survey techniques or because they do not report their paternity status (Rendall et al. 1999, Garfinkel et al. 1998). The so-called ‘missing fathers’ problem’ is especially serious among low income men. Thus a major objective of the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study was to obtain an accurate description of the capabilities of the men who father children outside marriage as well as the values and social skills of unmarred parents.

Table 1 presents data on the characteristics of new parents at the time of their child's birth.4 The table distinguishes between unmarried parents who are cohabiting and living apart because we expect these two types of unmarried couples to differ from one another. To date, we have not identified large racial or ethnic differences in our sample, and thus the information reported in the table is based on all parents. Where important differences exist, they will be noted in the text.

Table 1.

Capabilities of Parents at Birth: Socio-economic

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohab | Single | Married | Cohab | Single | |

| Age (mean) | 29.6 | 24.3 | 22.5 | 32.0 | 27.6 | 25.0 |

| Teen parent | 4.2 | 17.5 | 33.9 | 0 | 9.1 | 22.2 |

| Child with other partner | 13.6 | 39.5 | 32.8 | 16.4 | 38.5 | 38.9 |

| Race | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 50.9 | 22.5 | 14.9 | 51.1 | 16.9 | 8.8 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 11.6 | 29.4 | 49.9 | 13.0 | 34.4 | 59.2 |

| Hispanic | 27.0 | 44.0 | 31.6 | 27.7 | 46.8 | 26.7 |

| Other | 10.6 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 2.0 | 5.3 |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 18.0 | 41.5 | 48.0 | 21.5 | 40.7 | 44.3 |

| High school | 24.7 | 39.6 | 36.1 | 20.1 | 39.6 | 35.5 |

| Some college | 21.0 | 17.5 | 14.4 | 25.9 | 15.9 | 16.2 |

| College | 36.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 32.6 | 3.7 | 4.0 |

| Weeks worked (mean) | 46.2 | 42.2 | 42.7 | 47.5 | 45.1 | 40.7 |

| Earnings (mean) | 28,507 | 11,446 | 10,792 | 40,125 | 21,166 | 16,393 |

| Poverty status | 12.3 | 33.7 | 52.9 | 11.4 | 33.4 | 53.4 |

A brief comparison of the columns in Table 1 indicates that married and unmarried parents come from very different worlds. As compared with their married counterparts, unmarried parents are disproportionately African American and Hispanic; they are younger and more likely to be teen parents, and they are more likely to have children by other partners. Cohabiting parents are somewhat better off than non-cohabiting parents, but the gap with married parents is large for both groups. The high prevalence of “multi-partnered fertility” – defined as having children with different partners – is one of several important new findings to have emerged from the study. Whereas between 14 and 16 percent of married parents report having had a child with another partner, between 35 and 40 percent of unmarried parents report having done so (Carlson & Furstenberg 2006, 2007).

Perhaps the most striking difference between married and unmarried parents is the gap in education. Whereas a majority of married parents has attended at least some college, a large minority of unmarried parents has not even completed high school. And although both groups of parents report working a similar number of weeks in the past year, unmarried parents report much lower earnings and much higher poverty rates. The large marital status gap in human capital and earnings underscores the that fact that many unmarried parents are poor prior to having a child. To make sure that the differences we observe were not due to differences in the stage of the family life cycle, we redid the analyses for parents having a first birth. Limiting the sample in this way does not alter the disparities reported in Table1.

Table 2 presents data on the mental health and health behaviors of married, cohabiting and non-co-resident parents. We view these measures as good indicators of parents’ social-emotional skills and ability to form stable relationships.

Table 2.

Capabilities of Parents at Birth: Health

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohab | Single | Married | Cohab | Single | |

| Depression | 11.9 | 15.5 | 17.8 | 6.8 | 9.5 | 14.8 |

| Heavy drinking | 3.9 | 7.6 | 7.4 | 24.0 | 29.9 | 23.1 |

| Illegal drug use | 0.7 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 9.1 | 10.4 |

| Partner violence | - | - | - | 2.6 | 8.0 | 9.6 |

| Father incarcerated | - | - | - | 9.4 | 36.8 | 46.2 |

According to Table 2, unmarried parents – both cohabiting and non-co-resident – are more likely to suffer from depression than married parents and somewhat more likely to report more problems with alcohol (DeKlyen et al. 2006). Unmarried fathers are twice as likely as married fathers to have problems with drug use, three times as likely to be violent, and nearly seven times as likely to have been incarcerated in the past. Again, although cohabiting fathers look better than non-co-resident fathers on some indicators, the major gap is between married and unmarried fathers. Drug use and violence are likely to be under-reported in these data. However, there is no reason to expect that under-reporting differs by marital status which means that our estimates of the gap between married and unmarried parents is likely to be accurate. The high level of incarceration among unmarried fathers is particularly striking and underscores the fact that the changes in penal policy which occurred after 1980 have played an important role in the lives of these parents (Geller et al. 2006, Swisher & Waller forthcoming).

We found important race/ethnic differences in three domains: multi-partnered fertility, drug/alcohol problems, and fathers’ incarceration. In each domain, the marital status gap was smaller among Blacks than among whites and Hispanics, primarily because the behaviors were more common among married Blacks.

What is the nature of relationships in fragile families?

One of the most important questions in the ongoing debate over the role of non-marital childbearing in the reproduction of poverty is whether the relationship between unmarried parents is committed or casual. When we began our study, much of the existing research on unwed parents’ relationships was based on ethnographic studies which present a rather mixed picture (Waller 2002). Some researchers have reported that unmarried fathers are committed to their families but face serious barriers to forming a stable family because of limited resources (Sullivan 1989); others have argued that non-marital childbearing is the by-product of a ‘mating game’ in which young (uncommitted) men take advantage of young women's fantasies of marriage and motherhood to gain sexual favors (Anderson 1989); and still others describe a world composed of ‘good daddies and ‘bad daddies (Furstenberg et al.1992).

Thus, a major objective of the Fragile Families Study was to learn more about the nature of parental relationships at birth, including how parents viewed marriage, whether they expected to marry, and whether their relationships were of sufficient quality to sustain a long term commitment. We also sought to learn more about parents’ attitudes towards marriage and the extent to which gender conflict and mistrust were serious problems as some qualitative students have suggested. By following parents over time we hoped to gain information about the prevalence of stable relationships as well as the factors affecting stability. We also hoped to learn about new partnerships and new children and the extent to which these new unions represent a gain or a loss for children. Finally, we were interested in whether unmarried fathers were involved in the lives of their children. Research on divorced fathers had shown that father-involvement declines rather dramatically during the years following a divorce (Seltzer 1991) but whether this pattern extended to unmarried fathers was an open question. On the one hand, we might expect unmarried fathers to be more involved with their children than divorced fathers, given that many of these men are still romantically involved with the child's mother. On the other hand, we might expect them to be less involved given that the rights and obligations of unmarried fathers are less institutionalized (Nock 1998).

Relationships at birth

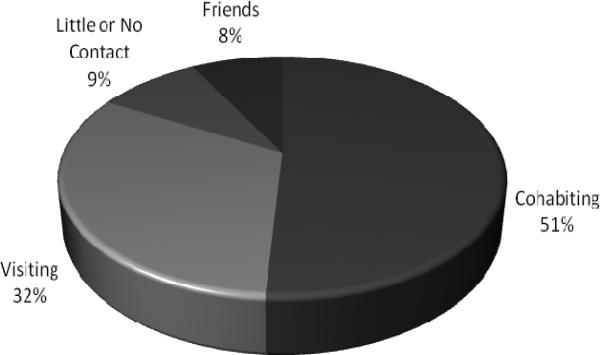

Figure 2 provides information on the nature of unmarried parents’ relationships at the time of the child's birth. As shown in the figure, over half of parents are cohabiting and another 32 percent are romantically involved. Less than 10 percent of mothers say they have ‘no contact’ with the father. Overall levels of romantic involvement are similar for whites, Blacks and Hispanics, although Blacks are less likely to be cohabiting at birth.

Figure 2.

Unmarried Parents Relationship Status at Birth

According to Table 3, most unmarried parents hold positive attitudes towards marriage, although not as positive as those of married parents (Waller & McLanahan 2005). Half of cohabiting mothers ‘strongly agree’ with the statement - it is better for children if their parents are married - and ninety percent say their chances of marriage are “fifty-fifty or better.” Non-cohabiting parents also hold positive views toward marriage although they rate their chances of marriage much lower.

Table 3.

Marriage Attitudes and Expectations at Birth

| All Mothers | White Mothers | Black Mothers | Hispanic Mothers | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | Cohab | Single | Married | Cohab | Single | Married | Cohab | Single | Married | Cohab | Single | ||||

| Pro-marriage attitudes | 72.6 | 49.3 | 49.3 | Pro-marriage attitudes | 67.7 | 40.3 | 27.19 | Pro-marriage attitudes | 81.2 | 58.9 | 53.9 | Pro-marriage attitudes | 74.4 | 49.1 | 52.7 |

| Approval of single mom | 57.6 | 80.7 | 85.4 | Approval of single mom | 46.8 | 75.2 | 74.7 | Approval of single mom | 72.5 | 83.2 | 89.1 | Approval of single mom | 74.6 | 80.5 | 88.2 |

| Gender distrust | 10.4 | 19.8 | 33.7 | Gender distrust | 3.3 | 11.1 | 20.1 | Gender distrust | 7.1 | 16.4 | 30.2 | Gender distrust | 25.7 | 28.3 | 45.9 |

| Supportiveness (mean) | 2.72 | 2.71 | 2.41 | Supportiveness (mean) | 2.77 | 2.73 | 2.34 | Supportiveness (mean) | 2.71 | 2.71 | 2.44 | Supportiveness (mean) | 2.61 | 2.69 | 2.36 |

| Conflict (mean) | 1.31 | 1.40 | 1.47 | Conflict (mean) | 1.31 | 1.44 | 1.40 | Conflict (mean) | 1.37 | 1.49 | 1.52 | Conflict (mean) | 1.30 | 1.35 | 1.44 |

| Chances of marriage | Chances of marriage | Chances of marriage | Chances of marriage | ||||||||||||

| Almost certain | - | 51.6 | 13.7 | Almost certain | - | 72.9 | 49.8 | Almost certain | - | 45.5 | 15.0 | Almost certain | - | 40.9 | 11.8 |

| Good | - | 26.0 | 17.1 | Good | - | 17.1 | 17.9 | Good | - | 30.7 | 18.1 | Good | - | 28.9 | 13.6 |

| Fifty/fifty | - | 14.5 | 19.7 | Fifty/fifty | - | 7.9 | 8.3 | Fifty/fifty | - | 15.0 | 22.8 | Fifty/fifty | - | 19.3 | 18.6 |

| Not so good | - | 4.0 | 12.5 | Not so good | - | 1.4 | 5.7 | Not so good | - | 3.2 | 12.9 | Not so good | - | 6.5 | 12.6 |

| No chance | - | 3.9 | 37.1 | No chance | - | 0.8 | 18.3 | No chance | - | 5.6 | 31.3 | No chance | - | 4.4 | 43.4 |

Finally, most parents describe their relationships as being “very supportive” and “low conflict” (scales range from 1 to 3 with 3 being high), with cohabiting parents being closer to married parents than to non-co-resident parents. Unmarried fathers are slightly more positive and more optimistic about their relationships than mothers (not shown in table).

We found only two areas in which unmarried parents’ attitudes might be described as less than positive towards marriage: first, unmarried mothers are much more likely than married parents to strongly agree with the statement that “a single mother can raise a child alone” and second, unmarried mothers are much more likely to agree with the statement “Men cannot be trusted to be faithful.” Cohabiting parents are closer to married parents in their beliefs about single mothers and in between married and single parents in gender distrust. Black mothers are more positive about marriage than white mothers, and the gap between married and unmarried parents is also smaller. Black mothers are also less likely than white mothers to believe that their chances of marriage are good. These findings are consistent with the argument that the increase in single motherhood has feedback effects on marriage, not by undermining positive attitudes towards marriage but rather by altering expectations and making single motherhood a more acceptable alternative. Hispanic mothers are the most likely to report distrust.

Relationships at five years

Despite their high hopes for a future together, only a small proportion of unmarried parents (22 percent) ever follow through on their plans, and even fewer (16 percent) are still married by the time of the five year interview. Counting both cohabiting and married parents, about one third of unmarried parents are living together five years after the birth of their child. Most of these parents were cohabiting at birth although some were romantically involved and living apart and a few reported ‘no romantic relationship’ at birth.

White and Hispanic mothers are more likely than African American mothers to marry the fathers of their children. Indeed, union dissolution overall is higher among Blacks than among other groups, in part because fewer parents are cohabiting at birth and in part because breakup rates are higher among Black couples irrespective of status. Much of the post-birth marriage gap between Blacks and whites can be accounted for by a shortage of ‘marriageable men,’ defined as the ratio of employed men to all women in a city (Harknett & McLanahan 2004). Black mothers are almost as likely to marry as white mothers when marriage market conditions are similar.

To learn more about their motivations for marriage, we conducted in-depth interviews with a subgroup of parents who participated in the core survey. When asked why they were not married, parents often said that they were waiting until they had achieved a certain standard of living which they viewed as necessary for a successful marriage (Gibson-Davis et al 2005). One young Hispanic father in his twenties put it this way:

I want to be secure....I don't want to get married and be like we have no money or nothing...I want to get my little house in Long Island, you know, white-picket fence, and two-car garage, me hitting the garbage cans when I pull up in the driveway (p. 619).

Mothers also emphasized the importance of sexual fidelity as a condition for marriage. Both rationales are supported by the quantitative analyses. Fathers’ income increases the chances of marriage and mothers’ distrust reduces the chances (Carlson et al. 2004). Furthermore, fathers (but not mothers) who have had a child by another partner are less likely to marry post birth. The fact that fathers’ multi-partnered fertility is more likely to undermine union stability than mothers’ suggests that multi-partnered fertility creates tension between the parents by causing a drain on fathers’ resources (time and money) and by creating conflict between the couple. In the qualitative interviews mothers often express jealously over the time fathers spend with a child who lives in another household, including jealously about the time he spends with the child's mother. This source of conflict is referred to as the ‘baby mama drama’ (Monte 2007).

New partnerships

Many unmarried parents have formed new partnerships by the time their child is age 5. About half of mothers who have ended their relationships with the biological father have a new partner (about 30 percent of all mothers), and two thirds are living with a new partner. Whereas we might have expected mothers’ new partners to be of lower quality than the original biological fathers—previous research suggests that having a child outside marriage reduces a woman's chances of marriage (Bennett et al. 2005)—in fact these men are of higher quality (Bzostek et al. 2006). New partners are much more likely to have a high school degree, more likely to be employed, less likely to have problems with drugs or alcohol, less likely to engage in domestic violence, and less likely to have been incarcerated than original biological fathers. Some of this improvement is due to aging and greater maturity and some is due to mothers being more selective in choosing new partners.

The high prevalence of new partnerships underscores an important feature of fragile families —high partnership instability. We estimate that by the time of the child's third birthday, two thirds of unmarried mothers have experienced at least one partnership change, over a third have experienced at least two changes, and nearly 20 percent have experienced three or more changes. In contrast, only 13 percent of married mothers have experienced a partnership change by the time their child is three and only 6 percent will have experienced two or more changes (Osborne & McLanahan 2007). Interestingly, the difference in partnership stability between married and unmarried mothers is not due to the fact that married mothers have fewer partnerships overall. Indeed, married mothers report having had more partners than unmarried mothers at the time of their child's birth. What is different, however, is that married mothers have not had children with their prior partners whereas unmarried mothers have. Despite the fact that many mothers are able to improve their living conditions by partnering with a new man, the search process itself can be stressful for both the mother and the child. Thus the gains associated with improving the quality of mothers’ partners may be offset by the losses associated with greater instability.

Biological fathers’ commitment

Most unmarried fathers are highly involved at birth (see Table 4), with cohabiting fathers showing much higher levels of involvement than non-co-resident fathers. According to mothers’ reports, over ninety percent of cohabiting fathers provided financial support and other types of help during the pregnancy, and 95 percent visited the mother at the hospital. Most importantly, nearly 100 percent of these men told the mothers that they wanted to help raise the child, and nearly 100 percent of mothers said they wanted the father to be involved (Johnson 2001). The proportions are lower for non-co-resident fathers with over half providing some type of support during the pregnancy and much higher levels reporting that they wanted to be involved.

Table 4.

Unmarried Fathers’ Involvement at Birth

| Cohab | Single | |

|---|---|---|

| Gave money/bought things for child | 95.3 | 64.1 |

| Helped in another way | 97.7 | 56.1 |

| Visited baby's mother in the hospital | 96.5 | 54.9 |

| Child will take father's surname | 93.1 | 63.9 |

| Father's name is on birth certificate | 96.0 | 71.0 |

| Mother says father wants to be involved | 99.5 | 89.3 |

| Mother wants father to be involved | 99.5 | 87.6 |

Despite their best intentions, just a little over a third of fathers are living with their children five years later, and there is substantial variation in the involvement of non-resident fathers: a third have no contact and 43 percent have monthly contact with their child. Among the latter, the average number of days a father sees his child is 12 per month (Carlson et al. forthcoming). Not surprisingly, the quality of the parents’ relationship is a strong predictor of fathers’ involvement (Waller & Swisher 2006). When the mother trusts the father and the parents are able to communicate about the child's needs, the father is more likely to visit and engage in activities with the child. Although one might argue that causality is operating in the opposite direction—father-involvement is leading to better cooperation—analyses indicate that most of the effect is going from cooperation to involvement (Carlson et al, forthcoming). Other factors that predict father-involvement include whether a father has a child by another partner (MPF), whether he was born outside the US, and whether he was ever incarcerated, all of which reduce parental cooperation and father-involvement.

Just over half of non-resident fathers provide some kind of financial support to their child and just under half provide in-kind support (Nepomnyaschy & Garfinkel 2006). Informal support is somewhat more common than formal child support at year five, although the proportion of mothers receiving formal support increases over time. Interestingly, stronger child support enforcement does not appear to increase the amount of money the father contributes, at least not during the first five years after birth. Rather, strong enforcement simply replaces informal payments with formal payments. When a mother receives welfare, formal child support payments are taken by the state to offset welfare costs which means that the mother has less income overall.

How do parents and children fare?

Marriage is expected to increase parents’ resources (financial, health, and social), which, in turn, is expected to improve children's home environments and future life chances. In theory, marriage increases family income by creating economies of scale and by encouraging parents to work harder and more efficiently (specialization) (Becker 1981). Marriage increases parents’ mental health by promoting social integration and emotional support (Gove, Hughes, and Style 1983). Finally, marriage increases access to social support by increasing neighborhood quality and residential stability and by expanding family networks and reinforcing family commitments (Coleman 1988). Each of these resources is important for the quality of the child's home environment.

The theoretical arguments for the benefits of marriage are supported by a large body of empirical research, including research on parents’ economic and social resources as well as research on outcomes for children and young adults (Waite 1995). Most of this research, however, is based on samples of adults (parents) who were married at birth and subsequently divorced. Thus, many questions remain about whether the benefits of marriage and the costs of union dissolution are as great for children born to unmarried parents. More importantly perhaps, research on the benefits of marriage and the costs of divorce is frequently criticized for making causal inferences from evidence of correlations.

Part of our rationale for following a cohort of new parents and their children was to determine whether the correlations between family structure and child outcomes found in previous studies were due to the number of parents in the household, the marital status of the parents, and/or the stability of the household. Specifically, we wanted to know whether the benefits of marriage extended to children raised in stable cohabiting parent families and whether the benefits of stability extended to households headed by a single mother.

A second motivation was to address the issue of causality by collecting better data on the specific mechanisms that are expected to mediate (or account for) the association between family structure and child outcomes. By starting with the birth of the child and by collecting data on a wide range of parental and relationship characteristics at the time of the birth, we hoped to be able to rule out some of the alternative arguments for why divorce and marital instability might be correlated with poor outcomes in children. For example, many analysts argue that divorce is a proxy for high conflict between parents. Thus we measured this construct at birth so that we could include it in our analyses. We also measured prior relationship instability, alcohol and drug abuse, anti-social behavior and incarceration history.

Finally, by identifying and measuring the key theoretical pathways linking family structure with child outcomes, we sought to test specific hypotheses about the causal processes underlying the correlation between family structure and outcomes, including hypotheses about the effects of non-marital childbearing on family income, parental health, social support, and parenting quality. While observational data can never provide conclusive evidence of causal effects, a more detailed description of the mechanisms that link family structure with particular outcomes is better than a simple correlation.

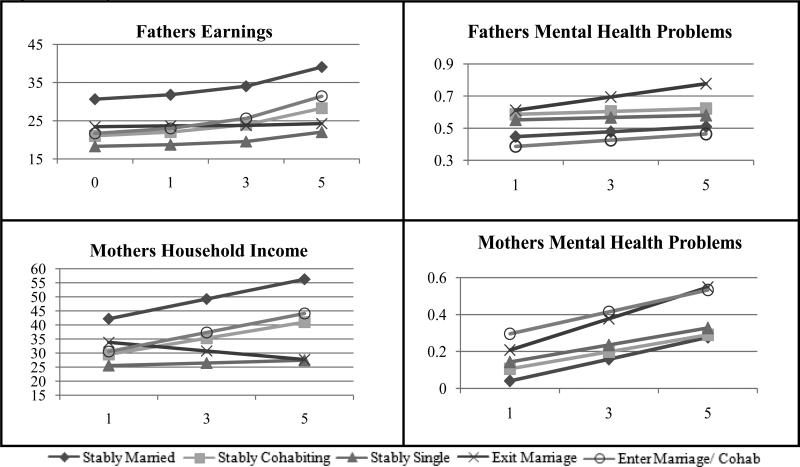

Fathers’ earnings and health trajectories

Figure 3 presents data on the trajectories of parents’ economic status and mental health during the first 5 years after the child's birth. Figure 3a provides data on fathers’ earnings; figure 3b provides data on fathers’ mental health; figure 3c provides data on mothers’ family income; and figure 3d provides data on mothers’ mental health. Parents are grouped according to their relationship status at birth and changes in relationships after birth. Thus we have couples in stable marriages, stable cohabiting relationships, relationships that break up and so on and so forth.

Figure 3.

Trajectories of Parents Income and Health

In examining the figures, two pieces of information are important: the starting point for each group (measured at birth) and the slope for each group. Both are adjusted for differences in fathers’ age, education, race/ethnicity and immigrant status. Looking first at the starting points in figure 3a, we see that fathers who are stably married report the highest earnings of all groups in the year prior to the birth.5 Below are married fathers who subsequently divorce, and last in line are unmarried fathers, followed by fathers who marry after the birth, fathers who are stably cohabiting and fathers who never cohabit (stably single). Note that all fathers experience earnings growth over time. However, fathers who divorce experience less of an increase than fathers who remain married which is consistent with previous research. Note also that fathers who marry after their child's birth experience a greater gain in earnings than unmarried fathers who remain single (Mincy, Garfinkel, McLanahan and Meadows 2008).

In separate analyses, we found that much of the relatively lower earnings growth of fathers who are stably single is due to the fact that these men have more mental health problems and are more likely to have been incarcerated than other fathers. When these factors are taken into account, the difference in earnings growth between those who marry and stably married fathers and stable single fathers cut in half. The lower earnings growth of single fathers is consistent with the argument that marriage increase fathers earnings. It is also consistent with the argument that women are less likely to marry men whom they view as having poor earnings trajectories.

The pattern for fathers’ mental health is somewhat different. Married fathers and fathers who subsequently marry report the fewest mental health problems at birth; fathers who subsequently divorce report the most mental health problems. Cohabiting and single fathers fall in between (Meadows 2007). All fathers experience increases in mental health problems over time, but there is no evidence of growing disparities. These results do not support the argument that marriage after birth helps close the gap in mental health between married and unmarried fathers.

Mothers’ economic status and health

As was true for fathers, married mothers are in much better economic condition than other mothers at the time their child is born. Single mothers who never marry report the lowest incomes. Most mothers experience improvements in economic status over time; divorced mothers are an exception. However, some groups of mothers experience smaller gains than others. Mothers who are stably single experience growing gaps with married mothers. Otherwise, unmarried mothers, including those who marry or move in with the father, experience income gains similar to those of stably married mothers.

Regarding mothers’ mental health, married mothers in stable unions report the fewest mental health problems at birth, whereas mothers who eventually divorce (or separate) report the most problems (Meadows et al. 2007). Mental health problems increase among all women after birth regardless of relationship status. In other analyses (not shown in the figure) we find that all partnership changes (entrances as well as exits) have short term negative effects on mothers’ mental health. The only exception is mothers who marry the fathers of their child before the child's first birthday; these mothers experience no short term increase in mental health problems.

Social support

Social support, defined as instrumental and emotional assistance from family or friends, is an important family resource, especially for new parents and single mothers (Cowan & Cowan 1992; Eggebeen & Hogan 1990). Social support serves as a form of insurance against poverty and economic hardship and is expected to improve the quality of the child's home environment by reducing parental stress. The Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study asked parents whether they knew someone who would loan them money, provide them with a place to live and/or provide childcare in case of an emergency. Using these measures, researchers find that unmarried mothers have less access to social support in the form of housing and cash assistance than married mothers. The disparity in support is due to several factors: first, access to support is higher in neighborhoods with higher median incomes (Turney & Harknett 2007), and unmarried parents are less likely than married parents to live in such neighborhoods. Second, access to support is positively associated with residential stability, and unmarried parents are less likely than married parents to have stable housing (Fragile Families Research Brief 2007). Indeed, unmarried parents are twice as likely as married parents to move during the five years following their child's birth and three times as likely to move three or more times.6 Finally, mothers who have children by different partners report having less access to support, especially financial support (Harknett & Knab 2007).

Parenting quality

Non-marital childbearing reduces the quality of parenting by contributing to partnership instability and multi-partnered fertility. Just as partnership changes reduce mothers’ income and increase mental health problems, we find that most types of instability (marriage to the biological father is an exception) increase maternal stress (Cooper et al. 2007). The negative effects of instability persist even after controlling for pre-disruption characteristics and parental resources. Importantly, the negative effects of partnership instability appear to be limited to mothers with a high school degree or less. Mothers with some college education do not report increases in maternal stress unless they experience multiple transitions.

Multi-partnered fertility also undermines the quantity and quality of parenting by reducing parents’ ability to get along and to cooperate in raising their child. Mothers report less support from the non-resident father and lower overall relationship quality when either parent has a child by another partner. Mothers also report less shared parenting and less cooperation in raising their child when the father has a child with another partner (Carlson and Furstenberg 2007).

Child wellbeing

Insofar as families formed outside marriage are quite diverse—ranging from stable co-habiting parent families to highly unstable families—distinguishing among these different types of households is likely to be important. Although we have only recently begun to examine how being born to unmarried parents affects child outcomes, the evidence garnered thus far suggests that both instability and material hardship have negative effects. Children who live with stably single mothers and children who live with mothers who experience multiple partnership changes show higher levels of aggression and anxiety/depression than children who live with stably married parents (Osborne & McLanahan 2007). In contrast, children who live with parents who are stably cohabiting do not differ from children raised by married parents. Half of the negative association between children's family context and behavior problems can be accounted for by the fact that single mothers and mothers in unstable partnerships report higher levels of maternal stress and are more likely to exhibit poor parenting.

Does non-marital childbearing contribute to the reproduction of poverty?

For non-marital childbearing to be a mechanism in the reproduction of poverty, it must be both a consequence and a cause of poverty. With respect to the first question, the findings from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study are consistent with the argument that unmarried mothers come from disadvantaged backgrounds and that low education reduces a mother's chances of forming a stable union after a non-marital birth. Although attitudes towards marriage and single motherhood also affect union stability, these differences do not negate the fact that factors associated with poverty play an important role in family formation.

With respect to the second condition, the evidence is also consistent with the argument than non-marital childbearing reduces children's life chances by lowering parental resources and the quality of parenting. Unmarried mothers experience less income growth, more mental health problems, and more maternal stress than married mothers. They also receive less help from the fathers of their children, and they have less access to much needed social support from family and friends. Each of these factors increases the risk of poor parenting.

Finally, these data highlight the importance of two causal mechanisms in the link between family structure and child outcomes: partnership instability and multi-partnered fertility. These conditions, which are inevitable consequences of a process in which women have children while they continue to search for a permanent partner, create considerable stress for mothers and children and reduce a mother's prospects of forming a stable union by contributing to jealousy and distrust between parents. Moreover, multi-partnered fertility increases the costs of children to fathers and thus reduces their willing to pay child support (Willis 2000). Finally, by spreading fathers’ contributions across multiple households, partnership instability and multi-partnered fertility undermine the importance of individual fathers’ contributions of time and money to the family economy which is likely to affect the future marriage expectations of both sons and daughters. In sum, the processes described above have important feedback effects on family formation, which retard upward mobility for children born to disadvantaged parents.

What is the solution?

In his report on the family, Moynihan argued that government policy should be directed towards enhancing the stability and resources of the African American family. Twenty years later, Wilson argued that government could strengthen the family by increasing employment opportunities and wages of low skilled men. For many years, neither message was heeded. Cash and in-kind benefits for poor families were highly income tested and thus not available to most two-parent families, creating large disincentives for marriage among low income parents. And the plight of poor unmarried fathers was virtually ignored except insofar as they were the target of child support enforcement. However, conditions changed in the early 1990s, beginning with the rapid expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit, which represented a substantial earnings subsidy for many two-parent families, and followed up by welfare reform legislation in 1996, which made it harder for a single woman to raise a child alone. Most recently, the federal government has begun funding programs designed to promote marriage by enhancing parents’ relationship skills and ability to manage disputes. While some portion of unmarried (and married) couples are likely to benefit from this new initiative, many will need additional help in order to form stable families, including mental health services, employment services, and help with reentry into their communities after incarceration (Garfinkel & McLanahan 2003).

Most importantly, none of these programs is likely to have a large effect as long as mothers continue to have children before they find a long term partner. Although wage subsidies and relationship counseling may ameliorate some of the problems associated with non-marital childbearing, they are likely to be limited in what they can accomplish. Thus, in order to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty, we will need to find a way to persuade young women from disadvantaged backgrounds that delaying fertility while they search for a suitable partner will have a payoff that is large enough to offset the loss of time spent as a mother or the possibility of forgoing motherhood entirely.

Acknowledgments

This paper was prepared for the conference on ‘The Moynihan Report Revisited: Lessons and Reflections after Four Decades,” sponsored by the American Academy of Political and Social Science, the Department of Sociology, Harvard University, and the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, Harvard University. The Fragile Families Study is supported by grants from NICHD and a consortium of private foundations. http://www.fragilefamilies.princeton.edu/

Biography

Sara McLanahan is the William S. Tod Professor of Sociology and Public Affairs at Princeton University. She directs the Bendheim-Thoman Center for Research on Child Wellbeing and is Editor-in-Chief of the Future of Children. Her research interests include family demography, inequality, and social policy. She has written 5 books, including Fathers Under Fire (1998), Growing Up with a Single Parent (1994), and Single Mothers and Their Children (1986), and over 100 scholarly articles.

Footnotes

Trends – National Center for Health Statistics (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr55/nvsr55_01.pdf, only goes as early as 1980)

What is new about the current debate is the argument that non-marital childbearing is not a problem but just an alternative family form (Stacey 1998, Coontz 1997). This position is based on the fact that non-marital childbearing is growing in all western industrialized countries and that in many countries (e.g. Sweden and France) a large proportion of non-marital births are to parents in stable cohabiting relationships (Chase-Lansdale et al. 2004).

A fourth question was “How do policies affect family formation and child wellbeing?”

Thanks to Kevin Bradway and Kate Bartkus for producing these numbers.

Sarah Meadows supplied the data for figure 1.

Rebecca Casciano provided these numbers.

References

- Anderson E. Sex Codes and Family Life Among Poor Inner City Youths. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1989;501:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gary. S. A Treatise on the Family. 1st edition Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett Neil G., Bloom David E., Miller Cynthia K. The Influence of Nonmarital Childbearing on the Formation of First Marriages. Demography. 1995;32(1):47–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzostek Sharon, Carlson Marcia, McLanahan Sara. Does Mother Know Best?: A Comparison of Biological and Social Fathers After a Nonmarital Birth. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2006. Working Paper #2006-27-FF. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Furstenberg Frank F. The Prevalence and Correlates of Multipartnered Fertility Among Urban U.S. Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(3):718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia J., Furstenberg Frank F. The Consequences of Multi-Partnered Fertility for Parental Involvement and Relationships. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2007. Working Paper #2006-28-FF. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia, McLanahan Sara, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Co-Parenting And Nonresident Fathers’ Involvement With Young Children After A Nonmarital Birth. Demography. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0007. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson Marcia, McLanahan Sara, England Paula. Union formation in Fragile Families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237–261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale Lindsay P., Kiernan Kathleen, Friedman Ruth J., editors. Human Development Across Lives and Generations: The Potential for Change. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. Human Capital in the Production of Social Capital. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Coontz Stephanie. The Way We Really Are: Coming to Terms with America's Changing Families. Basic Books; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Coontz Stephanie, Folbre Nancy. Marriage, Poverty and Public Policy.. Discussion Paper from the Council on Contemporary Families (CCF); Prepared for the Fifth Annual CCF Conference; New York. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Carey, McLanahan Sara, Meadows Sarah, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Family Structure Transitions and Maternal Parenting Stress. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2007. Working Paper #2007-16-FF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When Partners Become Parents: The Big Life Change for Couples. Basic Books; New York: 1992. Republished by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Fall 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen Michelle, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne, McLanahan Sara, Knab Jean. The Mental Health of Married, Cohabiting, and Non–Coresident Parents With Infants. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(10):1836–1841. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ. Family Structure and intergenerational Exchanges. Research on Aging. 1992;14:427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Fragile Families Research Brief, #40 . The Frequency and Correlates of Mothers’ Residential Mobility. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Sherwood KE, Sullivan ML. Report on Parents’ Fair Share Demonstration. Manpower Development Research Corporation; New York: 1992. Daddies and Fathers: Men Who Do for their Children and Men Who Don't. pp. 34–56. prepared for. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel Irwin, McLanahan Sara, Hanson Thomas L. A Patchwork Portrait of Non-Resident Fathers. In: Garfinkel, McLanahan, Meyer, Seltzer, editors. Fathers Under Fire: The Revolution in Child Support Enforcement. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1998. pp. 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Geller Amanda, Garfinkel Irwin, Western Bruce. The Effects of Incarceration on Employment and Wages: An Analysis of the Fragile Families Survey. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2006. Working Paper #2006-01-FF. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis Christina, Edin Kathryn, McLanahan Sara. High Hopes, but Even Higher Expectations: The Retreat from Marriage Among Low-Income Couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(5):1301–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Gove Walter R., Hughes Michael, Style Carolyn Briggs. Does Marriage Have Positive Effects on the Psychological Well-Being of Individuals? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:122–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen, Knab Jean. More Kin, Less Support: Multipartnered Fertility and Kin Support among New Mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(1):237–253. [Google Scholar]

- Harknett Kristen, McLanahan Sara S. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Marriage after the Birth of a Child. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(6):790–811. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Waldo E. Paternal Involvement among Unwed Fathers. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(6):513–536. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S. Categorically Unequal: The American Stratification System. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara, Sandefur Gary. Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows Sarah. Family Structure and Fathers’ Well-Being: Trajectories of Physical and Mental Health. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2007. Working Paper #2007-19-FF. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows Sarah O., McLanahan Sara S., Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Parental Depression and Anxiety and Early Childhood Behavior Problems Across Family Types. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(5):1162–1177. [Google Scholar]

- Monte Lindsay. Blended But Not the Bradys: Navigating Unmarried Multiple Partner Fertility. In: England, Edin, editors. Unmarried Couples with Children. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2007. pp. 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan Daniel Patrick. The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. United States Department of Labor, Office of Policy Planning and Research; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Murray Charles. Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980. Basic Books; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Nepomnyaschy Lenna, Garfinkel Irwin. Child Support Enforcement and Fathers’ Contributions to Their Non-Marital Children. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2006. Working Paper # 2006-09-FF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock Steven L. The Consequences of Premarital Fatherhood. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:250–263. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne Cynthia, McLanahan Sara. Partnership Instability and Child Wellbeing. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(4):1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Rainwater Lee, Yancey William L. The Moynihan Report and the Politics of Controversy. The MIT Press; Boston: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman Nancy E., Teitler Julien O., Garfinkel Irwin, McLanahan Sara. Fragile Families: Sample and Design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(45):303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall MS, Clarke L, Peters HE, Ranjit N, Verropoulou G. Incomplete Reporting of Men's Fertility in the United States and Britain: A Research Note. Demography. 1999;36:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan William. Blaming the Victim. Vintage Books; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer JA. Relationships Between Fathers and Children Who Live Apart. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53(1):79–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey Judith. Brave New Families: Stories of Domestic Upheaval in Late-Twentieth-Century America. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stack Carol. All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community. Harper & Row; New York: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan ML. Absent Fathers in the Inner City. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1989;501:59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Swisher Raymond, Waller Maureen. Confining Fatherhood: Incarceration and Paternal Involvement among Unmarried White, African-American and Latino Fathers. Journal of Family Issues. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Turney Kristin, Harknett Kristen. Neighborhood Disadvantage, Residential Stability, and perceptions of Instrumental Support Among New Mothers. Center for Research on Child Wellbeing; Princeton, NJ: 2007. Working Paper #WP07-08-FF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. Does Marriage Matter? Demography. 1995;32(4):535–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller Maureen R. My Baby's Father: Unmarried Parents and Paternal Responsibility. Cornell University Press; Ithaca: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Waller Maureen R., Swisher Raymond. Fathers’ Risk Factors in Fragile Families: Implications for ‘Healthy’ Relationships and Father Involvement. Social Problems. 2006;53(3):392–420. [Google Scholar]

- Waller Maureen R., McLanahan Sara S. ‘His’ and ‘Her’ Marriage Expectations: Determinants and Consequences. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Western Bruce. Punishment and Inequality in America. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Willis Robert. The Economics of Fatherhood. American Economic Review. 2000;90(2):378–382. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson James Q. The Marriage Problem: How Our Culture Has Weakened Families. Harper Collins; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson William Julius. The Truly Disadvantaged. Harvard University Press; Boston: 1988. [Google Scholar]