Introduction

In an editorial entitled, “A Presidential Blue Print for Success and Change”, Frederick Greene, M.D., previous Chair of the Commission on Cancer of the American College of Surgeons stated, “All of us dedicated to cancer care will gain much insight from the Graham Center’s blue print.”1 I hope that some of you in the audience today will be able to utilize in your own institutions some of the successes that we have had in our Cancer Program at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center at Christiana Care. To put the Cancer Program in context, Table 1 illustrates the 2008 key metrics for the Christiana Care Health Systems. I would point out that there were 42,362 surgical procedures, 3239 analytic cancer cases, and there are 229 Christiana Care residents and fellows as part of the independent training programs at Christiana Care approved by the American College of Graduate Medical Education. This includes a general surgery residency program that graduates five chief residents each year.

Table 1.

Christiana Care Health Systems Key Metrics for the Year 2008

| Emergency department visits | 146,736 |

| Admissions | 55,049 |

| Surgical procecures | 42,362 |

| Births | 7,249 |

| Cancer cases | 3,239 |

| Medical/dental staff | 1,432 |

| Medical students – Jefferson | 420 |

| CCHS residents/fellows | 229 |

The components for a successful community cancer program are: 1) a core of high quality well-trained professionals; 2) resources; 3) collaboration with institutions of higher learning; and 4) collaboration with community organizations. Building an academic community cancer center requires the collaboration of several institutions. Figure 1 demonstrates those institutions we have been fortunate enough to develop programs with over the last several years. As illustrated in Figure 1, the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center has three types of practices. The overwhelming majority of physicians are in private practice, and a small percentage are employed by Christiana Care. There is the third type, which I have labeled as “hybrid”. This is a situation where a private practice may be in the position to recruit an additional member. The Cancer Center at the same time may need a Director of the Breast Center or a Director of Translational Cancer Research, as examples. Hence, in a combined recruitment, that individual can be given a stipend by the Cancer Center as a director of these programs. The other component in Figure 1 is the State cancer control program of which the Delaware Cancer Consortium was formed in 2001 and launched its first statewide program in 2002 for colorectal screening. Delaware does not have the physical presence of a medical school. The chartered medical school of the state is Jefferson Medical College. Research agreements between the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and the Kimmel Cancer Center at Thomas Jefferson University and the University of Delaware were completed as part of the building process for an academic community cancer center. Figure 1 also demonstrates those community organizations with which the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center has collaborative efforts.

Figure 1.

The components that drive the Helen F Graham Cancer Center toward becoming an academic community cancer center.

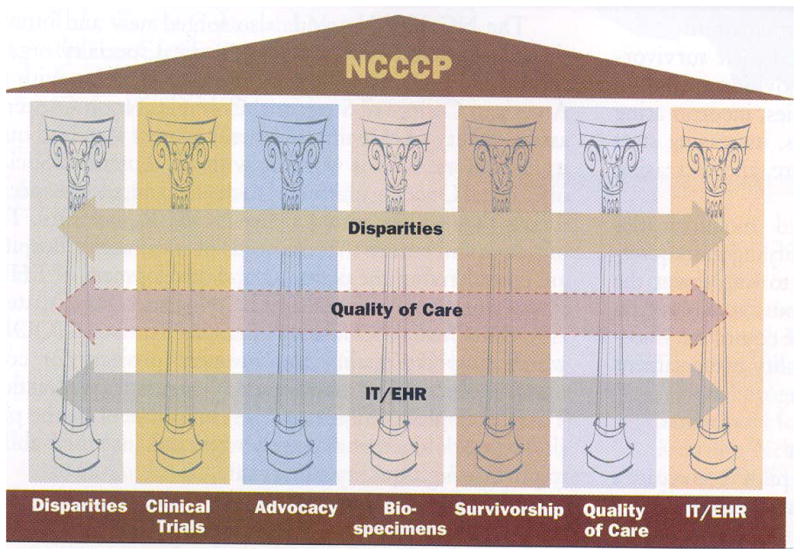

National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Center Program

Before I talk about the programs at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, I would like to spend some time on the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP). As Figure 2 demonstrates, this program has seven pillars that range from clinical trials to survivorship. These pillars are integrated with disparities, quality of care, information technology and electronic health records. The reasons for the establishment of the NCCCP are that 85% of cancer patients in the United States are diagnosed at hospitals in their communities where the remaining 15% are diagnosed at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) designated cancer centers, which are mainly in urban areas. Also, many patients are not treated at major cancer centers because of distance from home, personal or economic reasons.

Figure 2.

The activities of the National Cancer Institute Community Cancer Centers Program (NCCCP) which began in 2007. The NCCCP involves a network of 14 institutions representing a cross section of community hospitals and healthcare systems in the United States.

The goals of the NCCCP are as follows: 1) expanding clinical trials with an emphasis on minority recruitment; 2) establishing the multidisciplinary team approach to cancer care; 3) reducing cancer health care disparities; 4) developing quality of life best practice outcomes and survivorship programs; 5) developing a national database of electronic medical record by participating in the NCI Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid; and 6) collecting, storing, and sharing blood and tissue samples needed for translational cancer research.

I would like to briefly share with you the accomplishments over the last two years of the NCCCP. First, the Institutions have formed a network for clinical trials web-based tool to track patient demographics, protocol screening methods and enrollment details such as reasons for patients not participating in a clinical trial. Second, several institutions have adopted the Cancer Bioinformatics Grid Network. Third, a dashboard has been created with disparities metrics for each program’s focused area to track progress at the sites and to track pilot-wide disparities initiatives. Fourth, several Institutions have adopted the NCI best practices for biospecimen resources. Fifth, a genetic counseling and multidisciplinary care assessment matrix tool has been developed and a cost study of the project is also presently ongoing. The last accomplishment has been partnering of the NCCCP Institutions with NCI-designated cancer centers for early phase clinical trials and research projects.

It is my opinion that in the future, there will be three types of NCI designated cancer centers. We presently have two in view of the comprehensive cancer centers and the clinical cancer centers. I believe sometime in the future, NCI designated community cancer centers arising out of the NCCCP pilot will become a reality. This is a three year pilot which in June 2009 received a fourth year of funding.

Delaware Cancer Control Programs

As illustrated in Table 2, in 2009 it was projected there would be 4,690 new cancer cases in the state of Delaware. The overall population of Delaware is 870,653. You can see in Table 2 that lung, breast, prostate and colorectal cancer were the most common cancers diagnosed in the state. There are also a significant number of melanomas because of the beautiful beaches in the southern part of the state and subsequent unprotected sun exposure by individuals. It is important to note that Delaware continues to have the most rapid decline in cancer mortality in the United States (US), twice that of the US rate. In the past, Delaware was ranked number one in the Country for both cancer incidence and mortality. The American Cancer Society’s estimates for 2009 placed Delaware number eight in incidence and number eleven in cancer deaths.2

Table 2.

The Most Common New Cancer Cases in the State of Delaware for 2009

| Type of cancer | n |

|---|---|

| Lung | 800 |

| Breast | 600 |

| Prostate | 550 |

| Colorectal | 440 |

| Melanoma | 220 |

| Total | 4,690 |

Total population is 870,653.

In view of these results, what are the programs that have and will continue to play a role? First, we can review the state government programs. The Clean Indoor Air Act was passed in November 2002, and I will share results with you along with the recent results of the statewide Colorectal Screening Program. It is also important to note that an uninsured family of four in the state of Delaware making up to $120,000 per year can receive two years of cancer treatment. A human papilloma virus vaccine education program was started in 2007, but it is too early to discuss the impact of that program.

Together with state government programs, the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center has developed additional programs. I will discuss the Ruth Ann Minner High Risk Family Cancer Registry, the Delaware Christiana Community Clinical Oncology Program (CCOP) for NCI clinical trials, the multidisciplinary disease site centers, and the Center for Translational Cancer Research (CTCR) with further development of the Delaware Center for Cancer Biology. We have an extremely successful Cancer Outreach Program focused in the city of Wilmington, but there will not be time to discuss this project.

As far as the State cancer control programs, Figure 3 demonstrates the Delaware and National adult smoking trends. You can see that for the first time, the Delaware adult smoking rate is below the national average as illustrated in 2007. This is due to the Clean Indoor Air Act passed in November 2002 and also the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center Lung Cancer Prevention and Screening Institute, which has several smoking cessation programs. Another funded statewide program is the goal to screen all Delawareans 50 years of age and older for colorectal carcinoma. Figure 4 demonstrates the percent of adults who have ever had a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy by race. As noted in 2008, Delaware’s colorectal screening rate for Caucasians was 17% higher than the United States. For African-Americans, Delaware’s rate was 25% higher than the rest of the Country. As you can see in Figure 4 in the year 2008, the top two graphs demonstrate that the disparity in colorectal screening between Caucasians and African-Americans is now nonexistent.

Figure 3.

The adult smoking rate for Delaware compared to the national rate, 1997–2007. The adult smoking rate in Delaware is falling twice as fast as the national rate.

Figure 4.

The percentage of adults by race in Delaware who have undergone screening for colorectal cancer, 2002–2008. Note that in 2008 there was no disparity between African Americans and Whites.

Helen F Graham Cancer Center Programs

Genetic Counseling and Gene Testing

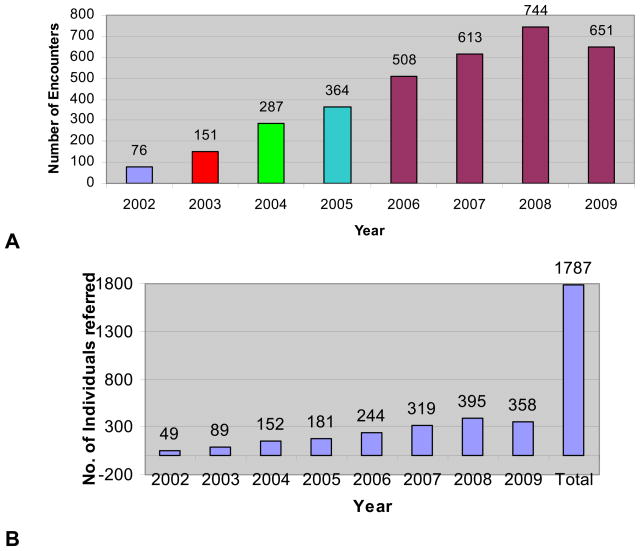

Prior to 2002, there was not one full-time adult genetic counselor in the state of Delaware. Since 2002, three full-time genetic counselors have been hired by the Cancer Center and have built a high-risk family cancer registry named after the former Governor, Ruth Ann Minner. This registry is the first and only program in the state with 1,539 families and 63,919 individuals. On a weekly basis, the genetic counselors visit the Tunnel Cancer Center at Beebe Hospital in the southern part of the state under the direction of James Spellman, M.D., the Commission on Cancer State Liaison for Delaware. This avoids the need for patients to travel to the northern part of the state to see the genetic counselors for evaluation. The genetic counseling program also started a primary care pilot in Kent County, in the middle of the state, in July of 2007 which continues to be successful. Figure 5 illustrates the total encounters and number of individuals referred to the genetic counselors has increased in each succeeding year since 2002, is due to a tremendous educational effort for both professionals and the public about the importance of family history in cancer care. The program results of individuals with gene alterations have resulted in 90%–95% of family members having an impact on their health care management. This has either been with the recommendation of prophylactic surgery, chemoprevention or increased surveillance. There is no question that the genetic counseling and gene testing program has contributed to the rapid decline in cancer mortality in the state of Delaware.

Figure 5.

The High Risk Family Cancer Registry established in 2002 demonstrating (A) the increase in total encounters by the genetic counselors (as of September 30, 2009) and (B) the number of individuals referred to the genetic counselors from 2002 to September 2009 (1,539 families; 63,919 individuals; as of September 30, 2009).

Clinical Trials

I would like to now turn our attention to the NCI Delaware Christiana Community Clinical Oncology Program. Because of the efforts of our physicians and our clinical research nurses, our NCI accrual to clinical trials increased from 14% in 2004 to 26% in 2008. Our accrual goal over the next three years is to reach 30%. The reasons for this high accrual are several. First, the established disease site multidisciplinary centers are staffed by clinical research nurses as part of the multidisciplinary team. These clinical research nurses know the details of the clinical trials just as well as the Principle Investigators. Second, we place a clinical research nurse in the physicians’ private offices only if they meet performance expectations. Third, we also have a monthly CCOP newsletter which we share with our satellites and a monthly CCOP meeting with trial review so that those trials that are not accruing over a certain period of time are brought to the “trial of the month” at Tumor Conferences to encourage physicians to talk to their patients about possible eligibility status. Lastly, we have an Annual CCOP Symposium where we give awards to the high accruing physicians. This includes surgeons who receive accrual credit if they refer a patient to a medical or radiation oncologist and that patient participates in a clinical trial.

On a monthly basis, we share with all of our physicians the accrual for treatment, cancer control, prevention, pharmaceutical and translational research trials so that they can see where their individual accrual status stands with their peers. A new program was started in January 2008 to help us reach this goal of 30% accrual rate. It involves clinical trial investigators earning their status. For a physician to maintain his or her clinical trials investigator status, they must meet certain criteria. 1) a minimum of four patients accrued per calendar year to NCI clinical trials; 2) they must attend one NCI Cooperative Group or CCOP research based meeting every other year; and 3) their medical records must undergo an audit in preparation for NCI Cooperative Group audits. Failure to meet these criteria means a loss of investigator status. Physicians can be reinstated, but they must wait one year, attend an NCI Cooperative Group meeting and pay a $500 fee.3 In 2008, this program resulted in five physicians accruing a total of 31 patients who previously, despite resources, had not accrued any patients on clinical trials over the previous 4 years.

Multidisciplinary Disease Site Centers

There are several key elements to the multidisciplinary care process. The first is a nurse navigator to coordinate scheduling and guide the patient through the complex maze of cancer care. The second is a needed centralized registration for one point of entry for the patient and to utilize information technology to communicate system wide. There also must be coordinated support care services, such as nutrition, social service, palliative care and pastoral care. The institution must also develop a model that can optimize professional and facility fee billing, especially in those institutions that depend on private practices. Lastly, all elements of the multidisciplinary care process must support an efficiently run system.

What is the buy-in for physicians to participate in multidisciplinary disease site centers? First, the patient’s treatment plan is established in a shorter time frame and face-to-face discussions with the three major disciplines of surgery, radiation and medical oncology along with support services, results in less biased decisions. As stated before, the multidisciplinary disease site centers also help increase accrual to clinical trials because the clinical research nurse is an important member of the multidisciplinary team. There is also better communication with the family by the three major disciplines since the family can meet with all disciplines in one visit. Once the multidisciplinary team members are organized, they can also build programs, such as the hepatoma screening program built by our Hepatobiliary Pancreatic Multidisciplinary Center.

There are four major elements for starting a multidisciplinary disease site center/clinic. The first, is a lead physician who can direct the center members and, in general, surgeons are the best qualified for this role. Second, physician members must buy into the vision of the cancer program. Third, a financial expert is needed to design and review a billing plan with hospital and legal counsel. Last, a leadership committee needs to be developed to design and review performance criteria and patient outcomes so that physicians maintain their high quality cancer care. Table 3 demonstrates the eleven performance expectations for physicians to participate in the multidisciplinary disease site centers.

Table 3.

The 11 Performance Expectations Required for Physicians to Participate in the Cancer Program

| Accrue patients to clinical trials yearly |

| Complete Institutional Review Board ethics training course. |

| 20 CME oncology credits every 2 years |

| Minimum 66% attendance at tumor conferences |

| Participate in professional cancer organizations |

| Complete specialty training in oncology and/or focused interest in 1 or 2 disease sites |

| Maintain a publication record or presentations at regional/national oncology conferences |

| Work with nurse navigators and support care services (ie, psychology, nutrition) as part of the multidisciplinary team |

| Monitor and improve clinical outcomes for patient cancer care |

| Teach oncology topics to trainees/paramedical personnel |

| Meet all criteria as an active staff member of the hospital |

TYP: set as list with no rules between rows.

It is important to note that the private practice physicians who participate in the multidisciplinary centers do their own billing. An example would be a patient who presents with a rectal cancer. If the multidisciplinary team decides that surgery would be performed first followed by chemoradiation, it is the surgeon who will bill the level 5 charge whereas the medical and radiation oncologist will be the two consultants.

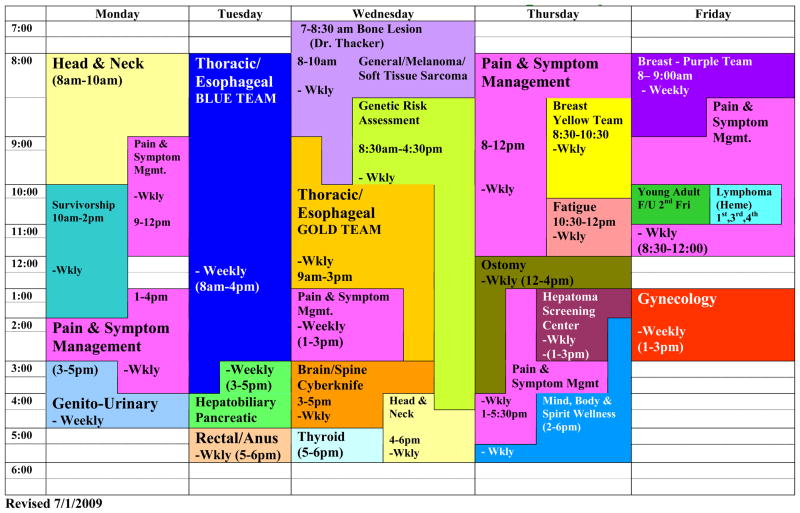

Initially, we started with three multidisciplinary centers. There was thoracic, head & neck, and a general oncology center to see other cancers. Figure 6 demonstrates the multidisciplinary disease site centers that we have today at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center. Aside from the disease site centers such as head & neck, thoracic, genitourinary, etc., there are also centers that deal with survivorship, pain & symptom management, and also an ostomy center. These centers have led to an increase in patient visits to the Cancer Center. In 2003, there were approximately 60,000 patient visits whereas in 2008, there were over 110,000 patient visits. Patient self-referrals have also increased from 44 patients in 2003 to 189 patients in 2008.

Figure 6.

The multidisciplinary disease site centers at the Helen F Graham Cancer Center. The centers are staffed by a surgeon, medical and radiation oncologist with the necessary support staff and physician subspecialties.

Program building also leads to the attraction of additional patients. This is best exemplified by 7,783 mammograms performed in 2001 whereas 16,658 mammograms were performed in 2008. Performance improvements of the multidisciplinary team have been illustrated by increasing stage III colon cancer patient referrals to medical oncology from 47% to 95%; reducing the average length of hospital stay by 0.67 days; reducing the waiting time for radiologic procedures from 2–3 weeks to 1 week, and in the case of CT scan from 1 week to 1 day; and lastly meeting the emotional, social, and spiritual needs of patients and their families.

The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer realizes that cancer conferences are an integral part of improving the care of cancer patients. We have been successful in establishing a statewide community cancer center videoconferencing program.4 As part of our tumor conferences, nurse navigators review the rate of compliance with tumor conference treatment recommendations. These recommendations are based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Center Network (NCCN) or the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines. In 2007, compliance with these recommendations was 92%, and in 2008 it was 85%. The data for 2009 is pending.

Translational Cancer Research

The last area I’d like to discuss concerns the question “Can a community cancer center be successful with a program of translational cancer research?” To establish a biomedical research initiative, there were two critical and growing building blocks in place in the state of Delaware. The first was the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, which opened in mid 2002, and the second was the Delaware Biotechnology Institute at the University of Delaware, which opened in 1999. The success of this biomedical research initiative has led to prevention, early detection, and treatment of major diseases where the initial focus has been on cancer. It has also resulted in cutting edge education and training for physicians, scientists, and students along with undergraduate and graduate internships. This includes a new undergraduate program of genetic counseling at the University of Delaware.

One of the goals of this biomedical research initiative was to create a medical school without walls, and the motto of the program was “failure is not an option”. Hence, Delaware’s medical and scientific community teamed up in 2003 to establish a nationally recognized biomedical research program in the state. This was the development of the Center for Translational Cancer Research (CTCR), which is now housed in the new pavilion of the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center expansion. The objectives of the CTCR were to create a center focused on coordinating clinical and basic science effort in translational cancer research within the state of Delaware utilizing managed core and research facilities at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute and the University of Delaware. Clinical partners would be those physicians at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center, and research and educational partnerships would be developed with the A.I. DuPont Hospital for Children/Nemours Research Institute in Delaware.

This effort has led to matching Helen F. Graham Cancer Center clinicians with scientists to foster better cancer care in the state. Examples of some of these NIH-funded projects are illustrated in Figure 7. The CTCR is also successful because of the development at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center of a Tissue Procurement Center, which has been funded from the NIH from 2003 to the present. The Tissue Procurement Center has over a thousand specimens inclusive of a database for patient demographics, disease and treatment status built on the NCI’s Cancer Bioinformatics Grid. The success of the CTCR and the Tissue Procurement Center led to funding for the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center to participate in the Cancer Genome Atlas Project in October 2008. The funding is $4.6 million over four years.

Figure 7.

Some of the grant funded projects of the Center for Translational Cancer Research illustrating the collaboration between physicians at the Helen F Graham Cancer Center and scientists at the University of Delaware. [MUST DELETE UNLESS PHOTOS ARE BLINDED OR PERMISSIONS OBTAINED]

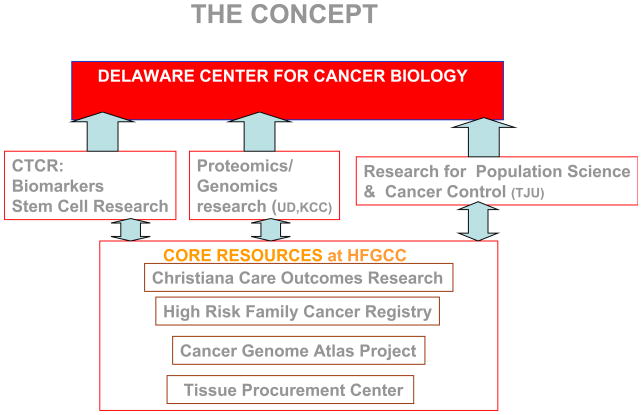

All of these efforts have led to a 124,000 square foot expansion of the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center which was dedicated in June 2009 and has doubled the space of the original Center. The expansion includes 6,000 square feet for the Center for Translational Cancer Research, which are the first ever wet labs on the campus of Christiana Care Health Systems. Figure 8 demonstrates that the vision has become a reality. In March of 2009, the Delaware Health Sciences Alliance was formed between Thomas Jefferson University, the University of Delaware, A.I. DuPont Children’s Hospital, and Christiana Care Health Systems. This vision will lead to the physical presence of the Delaware School of Medicine, which will be an extension of Jefferson Medical College and an expansion of the Center for Translational Cancer Research, which will be the Delaware Center for Cancer Biology. Figure 9 illustrates the concept for the Delaware Center for Cancer Biology inclusive of the biomarker and stem cell research programs of the CTCR and subsequently adding proteomics/genomics and research for population science and cancer control.

Figure 8.

The establishment of the Delaware Health Sciences Alliances involving Christiana Care Health Systems, Thomas Jefferson University, University of Delaware and AI duPont Childrens Hospital. This will establish the Delaware School of Medicine as an extension of Jefferson Medical College.

Figure 9.

The concept for the Delaware Center for Cancer Biology to be established from the infrastructure of the Center for Translational Cancer Research.

Summary

I believe that the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center program development along with statewide cancer control has transformed Delaware. Cancer mortality rates and the adult smoking rate in the state are dropping twice as fast as the national average. Cancer incidence is declining among African-Americans three times faster than among Caucasians. The Center for Translational Cancer Research and the Tissue Procurement Center have allowed clinicians at the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and scientists to work together and receive NIH grants. Importantly, NIH funding to Delaware grew six-fold from $5 million in 1995 to $30 million in 2008. The NCCCP has expanded the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center Outreach to underserved areas, increased minority recruitment to clinical trials and led to funding for the Cancer Genome Atlas Project.

The Helen F. Graham Cancer Center Outreach Program together with the state cancer control programs have resulted in Delaware being third in the United States for women who have received a mammogram in the last two years, third for women who have received a pap smear in the last three years, and first for individuals who have received a colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy in the last five years. The High Risk Family Cancer Registry, the multidisciplinary disease site centers, our Cancer Outreach Program, the NCI clinical trials, and Center for Translational Cancer Research are the strong foundation to build on for the Cancer Program in the next five years.

Conclusion

In conclusion, one can define program success in a community cancer center as follows: 1) gather a core of high quality individuals to buy into your vision and build programs; 2) keep the vision simple with five year strategic plan intervals; 3) work hard to get resources and utilize existing community organizations and resources; and 4) surround yourself with people who are smarter than you, but just don’t let them know that.

Footnotes

Disclosure information: Nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Green F. A presidential blue print for success and change. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2355–2356. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petrelli N, Grubbs S, Price K. Clinical trial investigator status: you need to earn it. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2440–2441. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickson-Witmer D, Petrelli N, Witmer D, et al. A statewide community cancer center videoconferencing program. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3058–3064. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]