Abstract

Most glutamatergic neurons in the brain express one of two vesicular glutamate transporters, vGlut1 or vGlut2. Cortical glutamatergic neurons highly express vGlut1, whereas vGlut2 predominates in subcortical areas. In this study immunohistochemical detection of vGlut1 or vGlut2 was used in combination with tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) to characterize glutamatergic innervation of the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) of the rat. Immunofluorescence labeling of both vGlut1 and vGlut2 was punctate and homogenously distributed throughout the DRN. Puncta labeled for vGlut2 appeared more numerous then those labeled for vGlut1. Ultrastructural analysis revealed axon terminals containing vGlut1 and vGlut2 formed asymmetric-type synapses 80% and 95% of the time, respectively. Postsynaptic targets of vGlut1- and vGlut2-containing axons differed in morphology. vGlut1-labeled axon terminals synapsed predominantly on small-caliber (distal) dendrites (42%, 46/110) or dendritic spines (46%, 50/110). In contrast, vGlut2-containing axons synapsed on larger caliber (proximal) dendritic shafts (> 0.5 μm diameter; 48%, 78/161). A fraction of both vGlut1- or vGlut2-labeled axons synapsed onto TPH-containing dendrites (14% and 34%, respectively). These observations reveal that different populations of glutamate-containing axons innervate selective dendritic domains of serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons, suggesting they play different functional roles in modulating excitation within the DRN.

Keywords: afferents, serotonin, spine, synapses, ultrastructure

Introduction

The dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) is a primary source of forebrain serotonin (Steinbusch et al., 1981; Molliver, 1987). As such, it has been implicated in arousal, anxiety and appetitive behaviors (Jacobs & Azmitia, 1992). In addition, dysregulation of the DRN is thought to contribute to mood disorders, including depression (Stockmeier et al., 1997; Stockmeier, 1997; Arango et al., 2002). The DRN receives and integrates afferent innervation from brain areas spanning from the medulla through the cortex (Kalen et al., 1985; Jacobs & Azmitia, 1992; Peyron et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2003). These afferents utilize a range of neurotransmitters and neuropeptide signals. Glutamate, through activation of multiple glutamate receptors, provides an important excitatory drive on the DRN (Pan et al., 1989; Tao & Auerbach, 1996, 2003; Jolas & Aghajanian, 1997). Both cortical and subcortical structures are known to provide glutamatergic innervation of the DRN (Kalen et al., 1985; Lee et al., 2003).

Glutamate neurotransmission both in cortical areas and within the DRN has been implicated in depressive illness (Paul & Skolnick, 2003). Using animal models, glutamate receptor antagonists have been shown to have antidepressant-like activity (Trullas & Skolnick, 1990; Maj et al., 1992; Papp & Moryl, 1996; Yilmaz et al., 2002). In addition, rapid eye movement sleep suppression, which decreases depressive symptoms, is reported to increase pontine glutamate in humans (Murck et al., 2002). These observations suggest glutamatergic innervation of the DRN may have importance for the progression of depression.

Previously it was technically difficult to anatomically study the distribution of glutamatergic axons because of the inability to differentiate the metabolic pool of glutamate from the neurotransmitter pool (Ottersen & Storm-Mathisen, 1984). However, the identification of the transporters that fill synaptic vesicles with glutamate has provided a better tool to identify glutamate-containing axon terminals in the brain (Fremeau et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001; Takamori et al., 2001; Kaneko & Fujiyama, 2002; Varoqui et al., 2002). The majority of glutamatergic neurons in the brain express one of two vesicular glutamate transporters, vGlut1 or vGlut2 (Fremeau et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001). Ultrastructural studies have demonstrated the localization of these transporters in synaptic (small-clear) vesicles within axon terminals (Bellocchio et al., 2000; Varoqui et al., 2002).

Identification of vGlut1 and vGlut2 provides the additional advantage of distinguishing different populations of glutamate axons that probably arise from different anatomic areas. vGlut1 expression predominates in cortical structures including hippocampus and cerebellum, whereas vGlut2 is widely expressed in subcortical areas with minor expression in cortical neurons (Fremeau et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001; Kaneko & Fujiyama, 2002; Kaneko et al., 2002; Varoqui et al., 2002). It has been suggested that the different vGlut isoforms may reflect different functional properties of the axon terminals. For example, axon terminals containing vGlut2 are thought to have higher probability of vesicular release then those containing vGlut1 (Fremeau et al., 2001), and are expressed in synaptic pathways that depend on high-fidelity neurotransmission. In contrast, vGlut1 is present in glutamatergic axon terminals that are associated with activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Varoqui et al., 2002).

In this study we examined the distribution of vGlut1 and vGlut2 to characterize glutamate innervation of the DRN using immunohistochemical methods with analysis at both the light microscopic and ultrastructural level. To determine the relationship specifically between glutamatergic axon terminals and serotonin neurons, immunolabeling for each vGlut individually was combined for that of tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH), the synthetic enzyme for serotonin.

Materials and methods

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia approved the experimental protocol used. Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (75 mg/kg) and were perfused transcardially through the ascending aorta with either 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PB, pH 7.6) for fluorescence microscopy or a combination of 2% paraformaldehyde and 3.75% acrolein in PB for electron microscopy. The brains were removed, cut into 3-mm blocks and left in the same fixative used for perfusion overnight. For light microscopy, brain blocks were equilibrated in 25% sucrose and sectioned frozen on a microtome. For electron microscopy, 50-micron-thick sections were cut using a vibratome, incubated with 1% sodium borohydride and then 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PB before immunohistochemical processing. In all cases, sections were processed free-floating.

Immunohistochemistry

Polyclonal antisera (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) raised against synthetic peptides from the rat vGlut1 or vGlut2 protein were used at a dilution of 1 : 2000. According to the manufacturer's specifications, preabsorption of these antisera with the immunogen peptide eliminates all immunostaining. In addition, immunolabeling using these antisera combined with immunolabeling for the same antigen with well-characterized antisera (Takamori et al., 2001) results in dual labeling of boutons in the spinal cord (Todd et al., 2003). vGlut1 and vGlut2 antisera were used in combination with a mouse monoclonal anti-TPH (clone WH-3; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) diluted 1 : 500.

For immunofluorescence detection, tissue sections were incubated with two primary antisera overnight at 4 °C, either vGlut1 and TPH or vGlut2 and TPH. After rinsing, labeling was visualized using Cy3 conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig in combination with Cy2 conjugated donkey anti-mouse secondary antisera. Secondary antisera had minimal cross-reactivity to other relevant species (Jackson Immuno-research). Sections were mounted, air-dried and coverslipped using an aqueous glycerol mounting media. Sections were examined using conventional immunofluorescence microscopy and digitally photographed.

For electron microscopy, sections were processed for dual labeling of either vGlut1 or vGlut2 and TPH. For this tissue sections were incubated with two primary antisera overnight at 4 ° with constant mild agitation. Tissue was then processed to visualize labeling of either vGlut1 or vGlut2 using the immunoperoxidase method. Sections were incubated with a donkey anti-guinea pig biotinylated secondary IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch) and then processed using the ABC Elite Kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at half the recommended concentration. Sections were incubated for 7 min with the chromagen 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (0.2 mg/mL). To label TPH using the immunogold-silver method (Chan et al., 1990), tissue was incubated in 0.5% BSA with gelatin followed by a 1-nm gold-conjugated secondary IgG (goat anti-mouse). After several rinses in 0.1 m Tris saline and 0.1 m sodium citrate pH 7.4, the gold particles were enhanced using a silver intensification kit (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA) for 8 min.

Sections were processed for electron microscopy after immunohistochemistry. For this the tissue was incubated in 2% osmium for 20 min and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol solutions, followed by propylene oxide. Tissue was embedded between two sheets of plastic using EMbed 812. Areas were selected for analysis from the DRN, primarily the medial portions. Thin sections (70 nm) of selected areas were stained using uranyl acetate and Reynold's lead citrate. Tissue was sampled from a minimum of two rostro-caudal levels from each rat. To establish the distribution of each vGlut with respect to TPH, tissue from four rats was examined and sampled from areas where both immunolabels were visible within 5 microns of each other. Twenty–40 labeled profiles were photographed from each rat. Additional profiles were examined but not photographed.

In descriptive quantitative analysis, axon terminals that could be distinguished to make contacts with other neural elements were analysed. Contacts included asymmetric and symmetric synapses as well as appositions. Asymmetric synapses were characterized by the close apposition of pre- and postsynaptic structures with a pronounced density on the postsynaptic membrane. Symmetric synapses were defined by the close apposition of membranes with equal electron density associated with both pre- and postsynaptic membranes with a minimal postsynaptic density. Appositions were close contacts between neural elements, but the morphology of the synapse could not be clearly defined. Dendritic spines were defined either by having a crescent or a mushroom cap-like shape or by the presence of endoplasmic reticulum indicative of a spine apparatus (Peters & Webster, 1991). Dendritic shafts had a rounded or ovoid shape and were divided into small caliber (< 0.5 microns measured at their longest dimension) or large caliber (> 0.5 micron diameter). To characterize the relationship between each transporter and TPH, the fraction of postsynaptic targets containing TPH labeling was determined. In addition, individual TPH-labeled dendrites were sampled, and the fraction of these that received contacts from transporter-labeled axons was determined.

Results

Immunofluorescence labeling for vGlut1 and vGlut2 consisted of discontinuous fine-grained dots covering the entire DRN and surrounding periaqueductal grey (Fig. 1). There was a slight increase in the density of labeling for both surrounded the aqueduct, otherwise distribution was uniform throughout the nucleus. vGlut2 immuno-labeling consistently appeared denser then vGlut1, and was only excluded from lucid areas that appeared to be cell soma. Visualizing dual-labeling immunofluorescence of each transporter with TPH, both vGlut1 and vGlut2 immunolabeling overlay TPH-containing cell bodies and processes (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of vGlut1 (A–C) and vGlut2 (D–F) immunofluorescence labeling in the DRN. (A) vGlut 1-immunolabeling consists of puncta that are homogenously distributed throughout the subregions of the DR. DM, dorsomedial portion of the DRN at the base of the aqueduct; IF, interfasicular; LW, lateral wing area. (B) Higher magnification of vGlut1-immunolabeling in the LWarea reveals discrete puncta. Asterisks indicate the location of TPH-labeled cell bodies. (C) Dual exposure with immunolabeling for TPH, asterisks mark the same cells as in (B). (D) Homogenous punctate labeling for vGlut2. (E) Higher magnification of vGlut2 in the LW. vGlut2-labeling appears denser then vGlut1 and lucid areas correspond to cell soma (asterisks and o). (F) Dual exposure with immunolabeling for TPH illustrates vGlut2 puncta surrounding TPH-labeled cell soma (asterisks) or probable unlabeled cell soma (o). Scale bars 120 μm (in A, for A and D); 100 μm (in C for B, C, E and F).

Ultrastructural analysis revealed vGlut1 immunolabeling was restricted to axon terminals (Figs 2–4). When a synaptic junction was visible, vGlut1-containing axon terminals usually formed asymmetric-type synapses (80%, 67/84), while the remainder appeared symmetric in morphology in single-section analysis (Fig. 3). However, when axons forming apparent symmetric-type synapses could be followed through serial sections, the synaptic contact appeared asymmetric (Fig. 4). The postsynaptic target of axon terminals containing vGlut1 was usually dendritic spines (44%, 48/110) or small-caliber (< 0.5 micron diameter) dendrites (35%, 39/110) that lacked labeling for TPH. Occasionally vGlut1 axons synapsed on spines connected to dendrites with immunolabeling for TPH or small-caliber TPH-labeled dendritic shafts (6%, 7/110). Only occasionally did vGlut1 axon terminals synapse on larger dendritic shafts that were unlabeled (6% 7/110) or contained TPH labeling (6%, 7/110). In some cases, vGlut1-containing axons were directly apposed to other non-TPH containing axon terminals without an intervening glial sheath (15%, 17/110) (Figs 3 and 4). However, when axo-axonic appositions were followed through serial sections frank synaptic contacts were not found (Fig. 4). Of 132 TPH-labeled dendrites sampled in close proximity to vGlut1-containing axons, 12 (8%) received direct contact from a vGlut1 axon.

Fig. 2.

(A) vGlut1-containing axons contacted small dendrites (< 0.5 microns in diameter) and spines, while vGlut2-containing axons predominantly contacted larger dendrites. Dendritic structures were either unlabeled (−TPH) or labeled (+TPH) for tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH). For vGlut1 n = 110, vGlut2 n = 138. (B) Both vGlut1 and vGlut2 contact TPH-containing dendrites at a similar rate when comparing by dendrite size. TPH-labeling may be less prevalent in smaller dendrites.

Fig. 4.

Serial-section analysis of contacts formed by vGlut1-containing axons. (A–D) Four serial sections through the same axon, which forms a synapse onto a dendritic spine (sp). A small labeled unmyelinated axon (a) is visible in each section. (A) A clear synaptic cleft is not visible although a slight density appears between the pre- and postsynaptic membranes (arrowhead). (B) The parallel close apposition of pre- and postsynaptic membranes (arrowheads) is indicative of a synaptic junction, which would be scored symmetric given the absence of any noticeable postsynaptic density. (C and D) A postsynaptic density is visible that appears more consistent with identification as an asymmetric-type synaptic contact (arrows). (E–G) Three serial sections through a vGlut1-labeled axon associated with other axons. (E) A vGlut1-labeled axon apposes without intervening glia (arrowheads) two axons, A1 and A2. A1 contains a low density of synaptic vesicles (v); A2 is adjacent to a tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH)-labeled dendrite (TPH). (F and G) The membranes remain closely apposed (arrowheads), but a frank synaptic contact is not discernable. (G is partially occluded by the grid bar). Scale, bars, 0.4 μm (in D for A–D, and in F for E–G).

Fig. 3.

vGlut1-immunolabeled axons (peroxidase-DAB) typically contacted small dendrites and dendritic spines. (A) vGlut1-labeled axon forms an asymmetric-type synapse (arrows) onto a dendritic spine (sp), and non-synaptically apposes another small structure (arrowheads). (B) A vGlut1-containing axon forms a long asymmetric-type synapse (arrows) onto an unlabeled dendritic spine (sp). (C) vGlut1-labeled axon forms asymmetric synaptic contacts (arrows) on a spine (sp) and non-synaptically apposes (arrowheads) a small unlabeled dendrite (uD), while a tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH)-labeled dendrite is visible in the field (TPH). (D) A less common case where a vGlut1 axon forms an asymmetric-type synapse (arrows) on a TPH-labeled dendritic shaft (TPH). The axon is also non-synaptically apposed (arrowheads) to an unlabeled axon (A). Another vGlut1-labeled axon is visible in the field (**). Scale bars, 0.4 μm (in D for A, B and D).

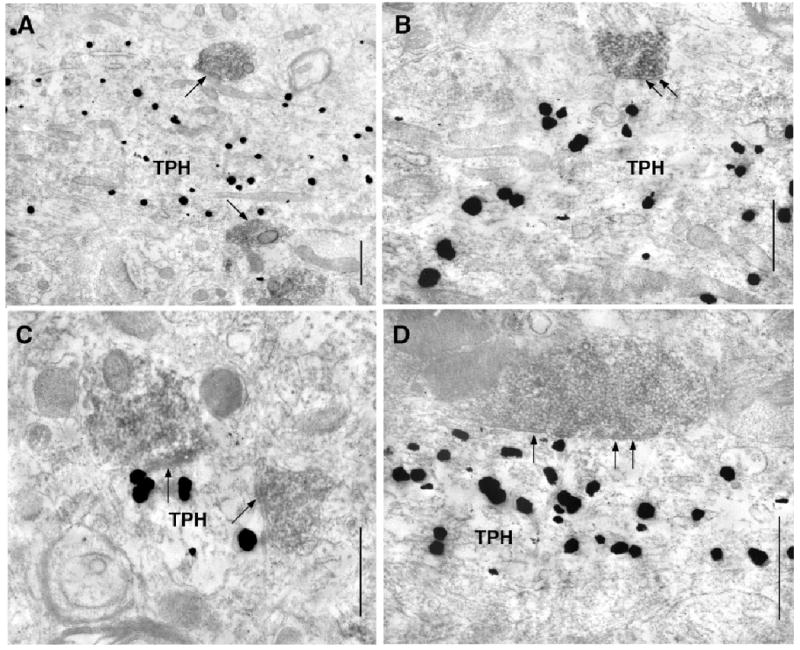

vGlut2 immunoreactivity was also restricted to presynaptic boutons (Figs 2 and 5). When a synaptic junction was visualized, vGlut2-labeled axons typically formed asymmetric-type synapses (95%, 131/138), although a few junctions appeared symmetric in morphology (5%, 7/138). The primary postsynaptic targets of vGlut2-labeled axons were unlabeled (23%, 37/163) or TPH labeled (25%, 41/163) dendritic shafts > 0.5 microns in diameter. Small-caliber dendrites contacted by vGlut2-containing axons usually lacked labeling for TPH (29%, 47/163), although a few contained TPH immunoreactivity (7%, 11/163). Dendritic spines contacted by vGlut2 axons were rarely labeled for TPH (15%, 24/163), although 1 (< 1%) contained TPH-labeling. Remaining postsynaptic targets were TPH-labeled cell soma (2). One hundred and twenty-five TPH-containing dendrites were sampled in close proximity to vGlut2 immunolabeling; of these 54 were visualized in contact with vGlut2-labeled axons (43%).

Fig. 5.

Direct contacts between vGlut2-labeled axons (immunoperoxidase) and tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH)-containing dendrites. (A and B) In single sections, two vGlut2-labeled axons contact (arrows) TPH-labeled dendrites (TPH). (B) Asymmetric synapses are clearly visible (arrows). (C and D) Examples of small (C) and large (D) vGlut2-labeled axons forming asymmetric synapses (arrows) on dendritic shafts containing immunogold labeling for TPH (TPH). Scale bars, 0.4 μm.

Discussion

This study demonstrates two populations of glutamatergic axon terminals in the DRN that have different anatomic relationships to serotonergic neurons. Axons containing vGlut1 innervated distal (small-caliber) dendrites and dendritic spines. In contrast, vGlut2-containing axons contacted dendritic shafts. These observations suggest these glutamatergic axons have divergent functional roles in modulating neural activity in the DR.

Methodological considerations

The antisera used to detect vGlut1 and vGlut2 result in highly selective immunolabeling of axon terminals consistent with the function of vGlut1 and vGlut2 in filling synaptic vesicles with glutamate (Bellocchio et al., 2000; Todd et al., 2003). The overall distribution of labeled axons is identical to previous studies using the same or different antisera directed against these transporters (Sakata-Haga et al., 2001; Kaneko & Fujiyama, 2002; Kaneko et al., 2002; Varoqui et al., 2002). TPH, the synthetic enzyme for serotonin, was used in preference to direct detection of serotonin, which is not feasible in acrolein-fixed tissue. The antisera used to detect TPH in this study does not immunolabel tyrosine hydroxylase-containing neurons in the DRN or locus coeruleus (unpublished observation), and resulted in a pattern of labeling consistent with previous descriptions of serotonin or TPH (Steinbusch, 1984). These lines of evidence suggest selective identification of vGlut1, vGlut2 and TPH proteins by the methods employed.

Several technical factors contribute to the potential for under-detection of both glutamate-containing axon terminals and serotonergic dendritic profiles. For example, glutamatergic axons not detected in this study may contain a different glutamate transporter, vGlut3, which is present in many neurons not traditionally thought of as glutamatergic (Fremeau et al., 2002; Gras et al., 2002). In addition, TPH may be more commonly sampled and more abundant in larger-caliber dendrites resulting in the under-detection of small dendrites and spines with detectable TPH labeling.

VGlut1- and vGlut2-containing axons synapsed on different types of dendritic profiles. VGlut1-containing axons favored dendritic spines and small-caliber axons, whereas vGlut2-containing axons typically synapsed on larger (> 0.5 μm diameter) dendrites. This organization is reminiscent of areas such as the hippocampus, where afferents from different regions selectively synapse on different portions of pyramidal cell dendrites, contributing to the laminar structure. In the simple instance when postsynaptic potentials decay passively from the dendritic tip, more proximal synaptic inputs have stronger influences on axon potential generation. However, selectively trafficking of ion channels as well as glutamate receptors to different zones of afferent innervation along the dendritic tree (Rubio & Wenthold, 1997) have the potential to impart more complex dendritic filtering properties.

vGlut1-containing axons often formed synapses on dendritic spines, specialized dendrite structures or compartments that are associated with synaptic plasticity (Bonhoeffer & Yuste, 2002; Gazzaley et al., 2002; Nikonenko et al., 2002). Spine density has been shown to increase with increased afferent activity (Kossel et al., 1997). This finding is consistent with speculation by others that vGlut1 may be associated with synaptic terminals that exhibit plasticity (Gazzaley et al., 2002).

Both vGlut1- and vGlut2-containing axons formed synaptic contacts on dendrites containing TPH labeling. In particular, there were numerous cases sampled of vGlut2-containing axons forming synapses on large TPH-containing dendrites. However, by analysing the frequency of axon contacts by size of the postsynaptic dendrite, there was no evidence that either vGlut1 or vGlut2 were selectively contacting TPH-containing dendrites. The abundance of vGlut2-containing axons coupled with the facility to detect TPH in large postsynaptic structures makes the innervation of TPH-labeled dendrites by vGlut2 axons striking. However, the most likely scenario is that vGlut1 and vGlut2 innervate both serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons.

Given the high expression of vGlut1 in cortical neurons in comparison to other brain areas (Fremeau et al., 2001; Hartig et al., 2003), vGlut1-containing axon terminals likely arise at least in part from the cortex. Several lines of evidence support the contention that cortical afferents to the DRN innervate non-serotonergic neurons. Anatomic studies have shown that afferents from the frontal cortex preferentially innervate γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-immunolabeled dendrites rather then those containing immunolabeling for TPH (Jankowski & Sesack, 2004). In addition, stimulation of the prefrontal cortex usually produces an inhibition of neurons recorded in the DRN that is not mediated by 5HT1A receptors, suggesting the activation of GABAergic inhibition (Hajos et al., 1998; Celada et al., 2001; Varga et al., 2001). Moreover, it has been shown that individual neurons in the DRN receive afferent innervation from both cortical and subcortical regions (the habenula) (Varga et al., 2003). Therefore axons containing vGlut1 and vGlut2 likely converge on common cell populations.

Most axons containing vGlut1 or vGlut2 formed Gray's type 2 or asymmetric synapses (Gray, 1969; Peters, 1991) characterized by a pronounced postsynaptic density. This would validate the correlation previously proposed between asymmetric synapses and glutamatergic neurotransmission (Uchizono, 1965; Cohen & Siekevitz, 1978). Occasionally synaptic junctions were judged as symmetric in single-section analysis; however, serial-section analysis suggests that these may be false-negative determinations of asymmetric synapses. Therefore the higher rate of symmetric synapses scored for vGlut1-containing axons may only reflect that the postsynaptic densities were smaller for these axons, compared with vGlut2. Thickening of the postsynaptic density can be produced by exposure to glutamate (Dosemeci et al., 2001) and is thought to be associated with recruitment of proteins to the postsynaptic density. The differing electron density of synapses formed by vGlut1- and vGlut-2-containing axons may correlate with different combinations or amounts of proteins at the postsynaptic density.

The finding that vGlut1- and vGlut2-containing axons synapse on distinct populations of dendritic structures suggests they may differentially impact excitation in the DRN. This parallels the observation that these transporters are expressed in different brain regions that are thought to play different functional roles. Areas that express vGlut1 and project to the DRN include the medial prefrontal cortex and, to a lesser extent, the insular cortex. The insular cortex preferentially innervates the lateral portions of the DRN (Reep & Winans, 1982), whereas the medial prefrontal cortex provides a more substantial and widely distributed innervation (Sesack et al., 1989; Vertes, 2004). Medial prefrontal cortex is associated in decision-making, goal-directed behavior and working memory (Goldman-Rakic, 1987, 1994; Petrides et al., 1995; Fuster, 2000), whereas the insular cortex is more often associated with sensation of visceral and emotional state (interoreception) (Saper, 1982; Craig, 2003).

Several areas that express vGlut2 are implicated in providing glutamatergic innervation of the DRN (Kalen et al., 1985; Lee et al., 2003). These include several hypothalamic nuclei associated with endocrine and feeding such as the lateral hypothalamic area, perifornical area and arcuate nucleus. In addition there are areas associated with cardiovascular control and sensation including the medial and lateral parabrachial and paragigantocellular nuclei (Kalen et al., 1985; Lee et al., 2003). In addition, DRN neurons receive glutamatergic innervation from adjacent glutamate neurons present in the DRN as well as the periaqueductal grey (Jolas & Aghajanian, 1997). Given the distinct expression pattern of vGlut1 and vGlut2, these areas are potential sources of these axons; however, confirmation would require additional dual-labeling tract tracing studies.

Conclusion

The present study describes the innervation of the DRN by axon terminals containing vGlut1 and vGlut2. These likely comprise the majority of traditionally glutamatergic afferents to the DRN and probably arise from cortical and subcortical areas, respectively. vGlut1-containing axons often synapsed on dendritic spines, a structure associated with synaptic plasticity. Postsynaptic targets of vGlut1-containing axons were usually small-caliber, suggesting input to distal dendrites of serotonin or non-serotonin-containing DRN neurons. In contrast, vGlut2-containing axons synapse on the dendritic shafts of serotonin neurons, likely providing a more direct afferent modulation of neurons in the DRN. Therefore, vGlut1 and vGlut2 define two different populations of glutamatergic afferents to the DRN.

Acknowledgments

Funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, USA (DA 00463, K.G.C.) the Groff Charitable Trust (K.G.C.) and the National Institute for Mental Health, USA (MH60773, S.G.B.).

Abbreviations

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- DRN

dorsal raphe nucleus

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- PB

phosphate buffer

- TPH

tryptophan hydroxylase

- vGlut1

vesicular glutamate transporter 1

- vGlut2

vesicular glutamate transporter 2

References

- Arango V, Underwood MD, Mann JJ. Serotonin brain circuits involved in major depression and suicide. Prog Brain Res. 2002;136:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellocchio EE, Reimer RJ, Fremeau RT, Jr, Edwards RH. Uptake of glutamate into synaptic vesicles by an inorganic phosphate transporter. Science. 2000;289:957–960. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhoeffer T, Yuste R. Spine motility. Phenomenology, mechanisms, and function. Neuron. 2002;35:1019–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celada P, Puig MV, Casanovas JM, Guillazo G, Artigas F. Control of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons by the medial prefrontal cortex: involvement of serotonin-1A, GABA (A), and glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9917–9929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09917.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Optimization of differential immunogold-silver and peroxidase labeling with maintenance of ultrastructure in brain sections before plastic embedding. J Neurosci Meth. 1990;33:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RS, Siekevitz P. Form of the postsynaptic density. A serial section study. J Cell Biol. 1978;78:36–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.78.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2003;13:500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(03)00090-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosemeci A, Tao-Cheng JH, Vinade L, Winters CA, Pozzo-Miller L, Reese TS. Glutamate-induced transient modification of the postsynaptic density. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10428–10432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181336998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Burman J, Qureshi T, Tran CH, Proctor J, Johnson J, Zhang H, Sulzer D, Copenhagen DR, Storm-Mathisen J, Reimer RJ, Chaudhry FA, Edwards RH. The identification of vesicular glutamate transporter 3 suggests novel modes of signaling by glutamate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14488–14493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222546799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:247–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM. Executive frontal functions. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:66–70. doi: 10.1007/s002210000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzaley A, Kay S, Benson DL. Dendritic spine plasticity in hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2002;111:853–862. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Development of cortical circuitry and cognitive function. Child Dev. 1987;58:601–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman-Rakic PS. Working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1994;6:348–357. doi: 10.1176/jnp.6.4.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras C, Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Pohl M, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. A third vesicular glutamate transporter expressed by cholinergic and serotoninergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5442–5451. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray EG. Electron microscopy of excitatory and inhibitory synapses: a brief review. Prog Brain Res. 1969;31:141–155. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63235-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajos M, Richards CD, Szekely AD, Sharp T. An electrophysiological and neuroanatomical study of the medial prefrontal cortical projection to the midbrain raphe nuclei in the rat. Neuroscience. 1998;87:95–108. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartig W, Riedel A, Grosche J, Edwards RH, Fremeau RT, Jr, Harkany T, Brauer K, Arendt T. Complementary distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters 1 and 2 in the nucleus accumbens of rat: relationship to calretinin-containing extrinsic innervation and calbindin-immunoreactive neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:1–10. doi: 10.1002/cne.10789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski MP, Sesack SR. Prefrontal cortical projections to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus: ultrastructural features and associations with serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:518–529. doi: 10.1002/cne.10976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolas T, Aghajanian GK. Opioids suppress spontaneous and NMDA-induced inhibitory postsynaptic currents in the dorsal raphe nucleus of the rat in vitro. Brain Res. 1997;755:229–245. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalen P, Karlson M, Wiklund L. Possible excitatory amino acid afferents to nucleus raphe dorsalis of the rat investigated with retrograde wheat germ agglutinin and D-[3H]aspartate tracing. Brain Res. 1985;360:285–297. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Fujiyama F. Complementary distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters in the central nervous system. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Fujiyama F, Hioki H. Immunohistochemical localization of candidates for vesicular glutamate transporters in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2002;444:39–62. doi: 10.1002/cne.10129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossel AH, Williams CV, Schweizer M, Kater SB. Afferent innervation influences the development of dendritic branches and spines via both activity-dependent and non-activity-dependent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1997;17:6314–6324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-16-06314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Kim MA, Valentino RJ, Waterhouse BD. Glutamatergic afferent projections to the dorsal raphe nucleus of the rat. Brain Res. 2003;963:57–71. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03841-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maj J, Rogoz Z, Skuza G, Sowinska H. Effects of MK-801 and antidepressant drugs in the forced swimming test in rats. Eur Neuropsycho-pharmacol. 1992;2:37–41. doi: 10.1016/0924-977x(92)90034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliver ME. Serotonergic neuronal systems: what their anatomic organization tells us about function. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1987;7:3S–23S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murck H, Struttmann T, Czisch M, Wetter T, Steiger A, Auer DP. Increase in amino acids in the pons after sleep deprivation: a pilot study using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuropsychobiology. 2002;45:120–123. doi: 10.1159/000054949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikonenko I, Jourdain P, Alberi S, Toni N, Muller D. Activity-induced changes of spine morphology. Hippocampus. 2002;12:585–591. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Glutamate- and GABA-containing neurons in the mouse and rat brain, as demonstrated with a new immunocytochemical technique. J Comp Neurol. 1984;229:374–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.902290308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan ZZ, Colmers WF, Williams JT. 5-HT-mediated synaptic potentials in the dorsal raphe nucleus: interactions with excitatory amino acid and GABA neurotransmission. J Neurophysiol. 1989;62:481–486. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.62.2.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M, Moryl E. Antidepressant-like effects of 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid and d-cycloserine in an animal model of depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;316:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul IA, Skolnick P. Glutamate and depression: clinical and preclinical studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:250–272. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters APS, Webster HD. The Fine Structure of the Nervous System. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Alivisatos B, Evans AC. Functional activation of the human ventrolateral frontal cortex during mnemonic retrieval of verbal information. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5803–5807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Petit JM, Rampon C, Jouvet M, Luppi PH. Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience. 1998;82:443–468. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reep RL, Winans SS. Efferent connections of dorsal and ventral agranular insular cortex in the hamster, Mesocricetus auratus. Neuroscience. 1982;7:2609–2635. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio ME, Wenthold RJ. Glutamate receptors are selectively targeted to postsynaptic sites in neurons. Neuron. 1997;18:939–950. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80333-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata-Haga H, Kanemoto M, Maruyama D, Hoshi K, Mogi K, Narita M, Okado N, Ikeda Y, Nogami H, Fukui Y, Kojima I, Takeda J, Hisano S. Differential localization and colocalization of two neuron-types of sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate cotransporters in rat forebrain. Brain Res. 2001;902:143–155. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB. Convergence of autonomic and limbic connections in the insular cortex of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1982;210:163–173. doi: 10.1002/cne.902100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Deutch AY, Roth RH, Bunney BS. Topographical organization of the efferent projections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tract-tracing study with Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. J Comp Neurol. 1989;290:213–242. doi: 10.1002/cne.902900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch HW, Nieuwenhuys R, Verhofstad A, Van der Kooy D. The nucleus raphe dorsalis of the rat and its projection upon the caudatoputamen. A combined cytoarchitectonic, immunohistochemical and retrograde transport study J Physiol (Paris) 1981;77:157–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbusch H. Serotonin-immunoreactive neurons and their projections in the CNS. In: Bjorklund A, Hokfelt T, Kuhar M, editors. Handbook of Chemical Neuroanatomy. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1984. pp. 68–121. [Google Scholar]

- Stockmeier CA. Neurobiology of serotonin in depression and suicide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;836:220–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockmeier CA, Dilley GE, Shapiro LA, Overholser JC, Thompson PA, Meltzer HY. Serotonin receptors in suicide victims with major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1997;16:162–173. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00170-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Rhee JS, Rosenmund C, Jahn R. Identification of differentiation-associated brain-specific phosphate transporter as a second vesicular glutamate transporter (VGLUT2) J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0002.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Auerbach SB. Differential effect of NMDA on extracellular serotonin in rat midbrain raphe and forebrain sites. J Neurochem. 1996;66:1067–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66031067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Auerbach SB. Influence of inhibitory and excitatory inputs on serotonin efflux differs in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei. Brain Res. 2003;961:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03851-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd AJ, Hughes DI, Polgar E, Nagy GG, Mackie M, Ottersen OP, Maxwell DJ. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters VGLUT1 and VGLUT2 in neurochemically defined axonal populations in the rat spinal cord with emphasis on the dorsal horn. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:13–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trullas R, Skolnick P. Functional antagonists at the NMDA receptor complex exhibit antidepressant actions. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;185:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90204-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchizono K. Characteristics of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in the central nervous system of the cat. Nature. 1965;207:642–643. doi: 10.1038/207642a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga V, Kocsis B, Sharp T. Electrophysiological evidence for convergence of inputs from the medial prefrontal cortex and lateral habenula on single neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:280–286. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga V, Szekely AD, Csillag A, Sharp T, Hajos M. Evidence for a role of GABA interneurones in the cortical modulation of midbrain 5-hydroxytryptamine neurones. Neuroscience. 2001;106:783–792. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varoqui H, Schafer MK, Zhu H, Weihe E, Erickson JD. Identification of the differentiation-associated Na+/PI transporter as a novel vesicular glutamate transporter expressed in a distinct set of glutamatergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2002;22:142–155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vertes RP. Differential projections of the infralimbic and prelimbic cortex in the rat. Synapse. 2004;51:32–58. doi: 10.1002/syn.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A, Schulz D, Aksoy A, Canbeyli R. Prolonged effect of an anesthetic dose of ketamine on behavioral despair. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;71:341–344. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00693-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]