Abstract

Calcium concentration may be a useful feature for distinguishing benign from malignant lung nodules in computer-aided diagnosis. The calcium concentration can be estimated from the measured CT number of the nodule and a CT number vs calcium concentration calibration line that is derived from CT scans of two or more calcium reference standards. To account for CT number nonuniformity in the reconstruction field, such calibration lines may be obtained at multiple locations within lung regions in an anthropomorphic phantom. The authors performed a study to investigate the effects of patient body size, anatomic region, and calibration nodule size on the derived calibration lines at ten lung region positions using both single energy (SE) and dual energy (DE) CT techniques. Simulated spherical lung nodules of two concentrations (50 and 100 mg∕cc CaCO3) were employed. Nodules of three different diameters (4.8, 9.5, and 16 mm) were scanned in a simulated thorax section representing the middle of the chest with large lung regions. The 4.8 and 9.5 mm nodules were also scanned in a section representing the upper chest with smaller lung regions. Fat rings were added to the peripheries of the phantoms to simulate larger patients. Scans were acquired on a GE-VCT scanner at 80, 120, and 140 kVp and were repeated three times for each condition. The average absolute CT number separations between the calibration lines were computed. In addition, under- or overestimates were determined when the calibration lines for one condition (e.g., small patient) were used to estimate the CaCO3 concentrations of nodules for a different condition (e.g., large patient). The authors demonstrated that, in general, DE is a more accurate method for estimating the calcium contents of lung nodules. The DE calibration lines within the lung field were less affected by patient body size, calibration nodule size, and nodule position than the SE calibration lines. Under- or overestimates in CaCO3 concentrations of nodules were also in general smaller in quantity with DE than with SE. However, because the slopes of the calibration lines for DE were about one-half the slopes for SE, the relative improvement in the concentration estimates for DE as compared to SE was about one-half the relative improvement in the separation between the calibration lines. Results in the middle of the chest thorax section with large lungs were nearly completely consistent with the above generalization. On the other hand, results in the upper-chest thorax section with smaller lungs and greater amounts of muscle and bone were mixed. A repeat of the entire study in the upper thorax section yielded similar mixed results. Most of the inconsistencies occurred for the 4.8 mm nodules and may be attributed to errors caused by beam hardening, volume averaging, and insufficient sampling. Targeted, higher resolution reconstructions of the smaller nodules, application of high atomic number filters to the high energy x-ray beam for improved spectral separation, and other future developments in DECT may alleviate these problems and further substantiate the superior accuracy of DECT in quantifying the calcium concentrations of lung nodules.

Keywords: computed tomography, lung nodule, phantoms, dual energy, quantitative CT

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in both men and women in the United States.1 In fact, it is responsible for more deaths than the next three most common cancers (colon, breast, and prostate) combined. In 2008, in the United States, it was estimated that 161,840 people would die from lung cancer.1 For all patients who are diagnosed with lung cancer, the expected 5 year survival rate is only 15.5%, which is considerably worse than the rates for cancer of the colon (64.8%), breast (89%), and prostate (99.9%).2 It is important to note that if the lung cancer is localized when it is first detected, the survival rate is about three times greater (49.3%) than the overall survival rate for all patients diagnosed with lung cancer.2 Although this positive outcome may in part be due to lead time bias, wherein the appearance of longer survival is a result of earlier diagnosis, early detection is still a worthy goal.

The computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) Research Laboratory at the University of Michigan is developing algorithms to detect and characterize lung nodules in CT images. One feature of the lung nodules that we are trying to detect and characterize is the amount and spatial distribution of calcium. Benign pulmonary nodules often contain a significant amount of calcifications with central, diffuse, laminated, or popcornlike patterns.3 The presence of calcifications is a very good indicator that the nodules are benign; however, this presence is not a perfect discriminator. Calcifications can also be present in a small percentage (∼6%) of primary lung cancers.4 The amount of calcium in a nodule might be determined from the measured CT numbers of the volume elements (voxels) within the nodule in the CT images of the patient. The CT number of a voxel is related to the effective linear attenuation coefficient (μ) of the tissues within the voxel relative to the μ of water. Since calcium has a greater μ than the other constituents of nodules, voxels that contain calcium in general have greater CT numbers. In order for us to use the amount of calcium in the nodules as a feature in CAD, it is necessary to evaluate the accuracy of CT numbers obtained with modern multidetector CT scanners.

We previously reported the results of an initial investigation in which simulated spherical lung nodules of various sizes and two CaCO3 compositions were scanned within lung simulating regions of an anthropomorphic thorax section phantom using various single energy (SE) scanning protocols.5 The purpose of the present study is to extend our previous work to examine the effects of patient body size, anatomical region, nodule size, and nodule position on SE and dual energy (DE) CT (DECT) number vs calcium concentration calibration lines and on resultant estimates of the calcium concentrations of nodules. It is expected that larger body habitus should result in greater x-ray beam hardening and x-ray scatter, which if uncorrected would decrease the CT numbers of nodules and result in greater CT number and calibration line nonuniformity with position in the lung field. Furthermore, based on our previous study,5 it is expected that larger lung∕air regions may result in decreased CT numbers of nodules. The reason for including DECT in the present study is that it should be more immune to the above effects and result in more accurate CT numbers.

The application of DECT to quantifying the amount of calcium in solitary pulmonary nodules was first proposed by Cann et al.6 In addition to compensating for inaccuracies in the CT numbers of nodules arising from the x-ray beams traversing through the very nonuniform and discontinuous structural environment of the chest, Cann et al. claimed that their DE approach should reduce the probability of incorrectly characterizing as calcifications the high CT number regions in some nodules that are due to dense fibrous tissues. This was based on their experimental phantom study using solutions of K2HPO4 in water to simulate diffuse calcifications and glycerol to simulate high-density fibrous nodules. High concentration K2HPO4 solutions and glycerol both had similar high SE CT numbers, but the differences between the CT numbers at low and high energies (DECT) were much smaller for glycerol than for K2HPO4. Our own (unpublished) calculations, under idealized conditions, support the assertion of Cann et al. of a smaller DECT number difference for fibrous nodules and even indicates a change in the polarity of the DECT results for such nodules. Using the NIST XCOM x-ray attenuation computer program,7 we estimate that the difference between the CT numbers of collagen (the principal protein of fibrous connective tissue) at low and high energies (e.g., 56 and 74 keV for an 80 kVp∕140 kVp DE technique8) is small and negative [e.g., 283 HU (Hounsfield units) −301 HU=−18 HU], whereas the CT number difference is positive and larger for a diffuse calcification (e.g., 326 HU–214 HU=112 HU for 200 mg∕cc CaCO3). It is interesting to note that negative CT number differences were obtained for some malignant lung nodules in a clinical study discussed below.

The DE technique of Cann et al. estimated the mineral content of a solitary pulmonary nodule from the measured CT numbers of the nodule in images obtained at 80 and 120 kVp and from the CT numbers of water and calibration standards of known mineral content. The equation employed was

| (1) |

where M is the mineral content of solitary pulmonary nodule in mg∕cc, H is the CT number of the solitary pulmonary nodule, W is the CT number of a “water” nodule at a corresponding location in a chest simulating phantom, s is the slope of a calibration line determined from the CT numbers and known mineral compositions of the calibration phantom that is scanned simultaneously with the patient, 80 represents 80 kVp, and 120 represents 120 kVp. To our knowledge Cann et al. only applied their method in phantom studies and in a small clinical study of ten patients.9 Their initial results indicated that calcium within pulmonary nodules could be quantified with DECT. Two other research groups in the US subsequently utilized DECT in larger clinical studies. Both groups used the difference between the CT numbers of the nodules at 80 and 140 kVp,

to characterize the calcium content of the nodules. In 1995, Bhalla et al.10 evaluated 27 solitary pulmonary nodules of patients who “presented for CT-guided needle aspiration biopsy.” They found that the CT number difference of 16 of the nodules were negative, and of these, 13 (81%) were malignant and 3 (19%) were benign. The CT number difference of 11 of the nodules were positive indicating the presence of calcium, and of these 10 (91%) were benign and 1 (9%) was malignant. Overall the DECT method had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 93%. In 2000, Swensen et al.11 reported the results of utilizing a similar DECT method in a multicenter study. They evaluated 157 indeterminate lung nodules prospectively. All of the nodules were solid, relatively spherical, 5–40 mm in diameter, homogeneous, and without visible signs of calcifications or fat. They found that the median CT number differences were 2 HU for benign nodules and 3 HU for malignant, and these differences were not statistically significant. Therefore, they concluded that DECT analysis “with current CT technology does not appear to be helpful in the identification of benign lung nodules.” The contrary results of these two studies may be due to differences in the study populations and DECT methods. Swensen et al. only studied indeterminate solid spherical nodules that had no evidence of calcifications or fat, whereas it does not appear that Bhalla et al. used as strict selection criteria. In addition, Bhalla et al.10 determined the CT numbers of their nodules by averaging the values in regions of interest (ROIs) in three adjacent slices, whereas Swensen et al.11 used a single ROI “carefully constructed to approximate the transverse shape of the nodule.” While the latter may seem reasonable, in separate unpublished experimental studies of spherical lung nodules in anthropomorphic phantoms we found differences as large as 26% between the mean CT numbers in adjacent slices near the centers of the nodules. We concluded that it is difficult to manually select a single slice to represent the mean CT number of a nodule. Therefore for our single energy (SECT) and DECT studies we employ an automated segmentation method5 described briefly in Sec. 2C, below.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phantoms

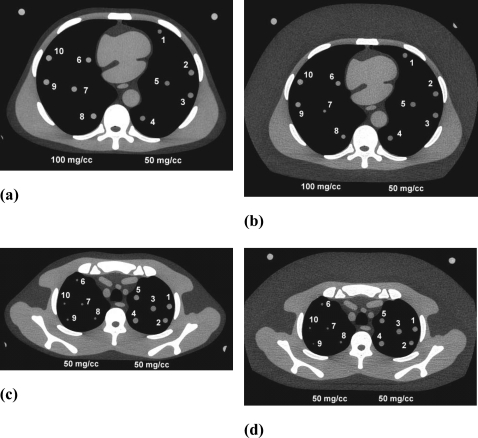

The same anthropomorphic thorax section phantom with foam lung regions that was used in our previous study5 was used in this investigation. As before, the phantom was bolused on both sides (in the z direction) with water equivalent sections of the same shape as the thorax section including open lung regions. Bolusing increased the effective thickness of the thorax section phantom from 2.3 to 8.1 cm which is useful for multidetector CT scans in which the total x-ray beam collimation can range from 1 to 4 cm. New for this study was the employment of fat and water equivalent plastic rings that could be added to the peripheries of the thorax phantom and the bolus sections to simulate large patients. Finally a completely different thorax section representing an upper section of the thorax with considerably smaller lung regions and greater muscle and bone portions was also studied. Custom-fitted bolus sections and additional fat equivalent and water equivalent rings were also applied to this smaller thorax section. For each phantom setup, petroleum jelly was spread on the faces of the adjacent thorax and bolus sections and the sections were squeezed together to eliminate air gaps with the vice system described in our previous publication.5 The simulated nodules employed in our previous study, i.e., 4.8, 9.5, 16 mm diameter spherical balls of CaCO3 in water equivalent plastic, were inserted into the lung regions. There were five 50 mg∕cc CaCO3 nodules of each size and five 100 mg∕cc CaCO3 nodules of each size, for a total of 30 nodules. All phantom sections and nodules were manufactured by Computerized Imaging Reference Systems, Inc. (CIRS Inc., Norfolk, VA). Representative examples of the CT images of the phantoms are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

CT images of some of the conditions studied showing the positions of the simulated lung nodules. (a) Middle thorax section, no fat ring, all 9.5 mm nodules, 50 mg∕cc on right, 100 mg∕cc on left. (b) Same as (a) but with fat ring. (c) Upper thorax section, no fat ring, all 50 mg∕cc, 4.8 mm nodules on left, 9.5 mm on right. (d) Same as (c) but with fat rings. Note that the nodules are not all perfectly centered in the z direction in a given slice. As a result, some may appear slightly larger or smaller than others of similar size [e.g., nodule 7 in (b) appears smaller].

CT scans

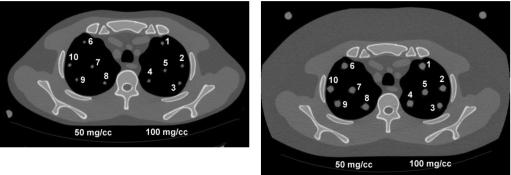

All CT scans were performed on a General Electric LightSpeed VCT scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) using the high resolution 120 kVp technique [400 mA, 0.8 s, 32×0.625 mm2 slices, 0.3 mm slice interval (0.625 mm interval for 9.5 mm nodules in the middle thorax), 0.531:1 pitch, large scan field of view, 36 cm display field of view] employed in our previous work.5 In addition, images were generated using the same high resolution parameters but at 80 and 140 kVp. Scans for each condition were repeated three times. In order to generate CT number vs CaCO3 concentration calibration lines at each lung nodule location for this study, images were acquired with both the 50 and 100 mg∕cc nodules of a particular size at the same locations in the lung regions of the thorax sections. Scans were performed with and without the added fat rings for both thorax sections. Preliminary analysis of the above scans yielded the unexpected outcome that the DECT results for the 4.8 mm diameter nodules in the upper thorax section were considerably worse than the SECT results. This was the opposite of the results in the middle thorax section. A review of the data did not show any obvious outliers and in order to verify that these results were true and not just a statistical anomaly, the scans in the upper thorax were repeated about 8 months later. Locations of the simulated lung nodules for these scans are illustrated in Fig. 2, below. The locations were chosen to be the same in the right lung of the upper thorax phantom as before with a mirror image in the left lung to include an anterior position 1 that is like 6, where the CT numbers in the initial study were found to be elevated.

Figure 2.

Examples of images acquired in second experiment using the upper thorax section showing numbered locations of simulated nodules. Left: Thorax section without fat ring with 4.8 mm diameter nodules. Right: Thorax section with fat ring with 9.5 mm diameter nodules.

The simulated nodules were positioned by hand within slits in lung simulating foam. Consequently, the centers of nodules were not necessarily coplanar in the z direction. Measurements made on all of the images in this study show that the mean maximum z offsets and range of maximum z offsets (in parenthesis) between the centers of the five individual nodules of each size in the lung fields were 2.0 mm (1.2–3.3), 3.0 mm (1.6–4.9), and 3.8 mm (2.9–4.7) for the 4.8, 9.5, and 16 mm nodules, respectively. The nodules were all scanned well within the 23 mm thick thorax sections which are cylindrically symmetric. Thus the nodule surroundings should be the same regardless of the z offset, and the offsets should have had no effect on the measured CT numbers of the individual nodules.

Analysis

Automated computation of mean CT numbers of nodules

Representative mean CT numbers were determined using the automated techniques described in our previous publication.5 In brief, a 3D active contour algorithm was employed to segment the nodules within 3D volumetric images which were interpolated to have isotropic voxels. For nearly all cases in the present study, the slice interval was 0.3 mm, which was smaller than both the slice thickness, 0.625 mm, and the pixel size in the axial slices, 0.703 mm, so that the pixel dimensions in the slices were interpolated to 0.3 mm by bilinear interpolation to achieve isotropic dimensions. The weighted centroid of each nodule was computed, and spherical VOIs that were 10% of the total volume of the segmented volume were centered at the centroid for the computation of the mean CT numbers. The 10% value was chosen empirically based on our experience that a VOI of this size was large enough to reduce noise fluctuation but was far enough from the nodule boundary to minimize partial volume effects. Also, as mentioned in our previous publication, the radius of such a 10% VOI is approximately equal to one-half the radius of the segmented nodule.5 The number of 0.3×0.3×0.3 mm3 voxels contained in the 10% volumes were about 240 for the 4.8 mm diameter nodules, 1770 for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules, and 7720 for the 16 mm diameter nodules.

Single energy CT calibration lines

Slopes and intercepts of the SECT calibration lines of CT number vs CaCO3 concentration for each nodule position were computed from the average CT numbers of the 50 and 100 mg∕cc CaCO3 nodules at those locations using the equations

| (2) |

| (3) |

where CT number is the average of the mean CT numbers for three identical scans each automatically determined within spherical VOIs of the specified 10% volume located at the centroid of the segmented nodule.

Dual energy CT

The DECT numbers were computed by taking the difference between the mean CT numbers of the nodules at 80 and 140 kVp.

Average absolute CT number difference

The effects of different conditions (e.g., different body size or different nodule size) on the calibration lines was determined by computing the average absolute CT number difference between the calibration lines for each condition. As an illustration, consider the comparison of the calibration lines determined with and without the additional fat rings. The general equation for computing the average absolute difference between the calibration lines is

| (4) |

where the comparison is determined over a user selected range of CaCO3 concentrations (x) going from “min” to “max,” y is the ordinate [CT number for SECT and (CT number at 80 kVp–CT number at 140 kVp) for DECT], m is the slope of the calibration line, b is the y intercept, and subscripts nfr and wfr represent no fat ring and with fat ring, respectively.

For this investigation, we chose to perform the computations over a concentration range of 0–200 mg∕cc CaCO3, where 200 corresponds to a concentration that is approximately twice that which produced the threshold CT number (on a GE 9800 CT scanner) of a reference standard for distinguishing benign from malignant pulmonary nodules in the original quantitative CT work of Zerhouni et al.12 Extrapolation of measurements made at 50 and 100 mg∕cc to 0 and 200 mg∕cc for the calibration lines is justified since for similar mineral standards, Cann et al.6 found that calibration lines are linear between 0 and 400 mg∕cc (K2HPO4 in water) and Im et al.13 found that calibration lines are linear between 0 and 310 mg∕cc [Ca(OH)2 in paraffin].

For our implementation, rather than utilize solutions to the integral equations, we computed the absolute displacements between the calibration lines from 0 to 200 mg∕cc in steps of 1 mg∕cc with a SAS routine (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC), summed those displacements, and divided the result by 200. A comparison of the values computed with this implementation and one using solutions to the above integral equations for five test cases showed that the values were identical.

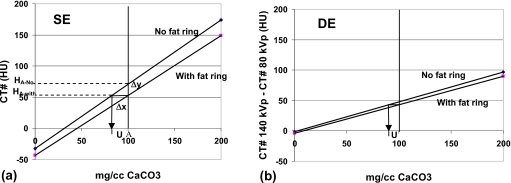

Average over- or underestimates in CaCO3 concentration

Average over- or underestimates in CaCO3 concentrations were calculated for cases in which calibration lines that were derived for one condition are applied to the CT numbers measured under another condition. For example, the calibration lines for “small” patients might be applied to the CT number measurements of pulmonary nodules in the “large” patients. Similarly, the calibration lines for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules might be applied to the 16 mm and∕or 4.5 mm diameter nodules, and those for nodules in the inner locations might be applied to those in the outer locations. The case in which the SECT calibration lines for the nodules in the small patient are applied to the SECT numbers of the nodules in the large patient is illustrated in Fig. 3a. The corresponding case for DECT is illustrated in Fig. 3b.

Figure 3.

(a) Calibration lines (top, without fat ring; bottom, with fat ring) for single energy estimates of CaCO3 concentration of pulmonary nodules showing underestimate (u) that would result if the calibration line for the small phantom (no fat rings) is used to calculate the CaCO3 concentrations of nodules in the large phantom (with fat rings) HA-no and HA-with are the CT numbers without and with the added fat rings for a nodule of concentration A. (b) Corresponding calibration lines and underestimate (u) are for dual energy.

The over- or underestimates in the CaCO3 concentrations for both the SE and DE cases illustrated in Fig. 3 were determined by dividing the vertical displacements between the “with” and “no” fat rings calibration lines by the slope of the “no fat ring” calibration line. This relationship can be derived as follows:

Let mno fat ring be the slope of the calibration line without fat ring and Δyi and Δxi be the change in CT numbers and change in concentrations for lesion i, respectively. From Fig. 3a,

| (5) |

Rearranging this equation,

| (6) |

and the average underestimate average

| (7) |

where Δymean is the average distance between the with and no fat rings calibration lines in the 0–200 mg∕cc concentration range (N=200), as in Eq. 4, above.

In most cases, the calibration lines with and without the fat rings do not intersect, and as calculated in Eq. 4. To convey representative under-∕overestimates and avoid potential ambiguities in which there are overestimates before the intersection of such calibration lines and underestimates beyond or vice versa, the under- or overestimates were computed using Eq. 6 with the Δy determined at a concentration of 100 mg∕cc CaCO3. This concentration was selected because it yields CT numbers on a GE scanner that are very similar to those of the reference nodules employed in the original reference phantom technique of Zerhouni et al. to distinguish benign from malignant lung nodules.5, 12 In that technique, one of the criteria employed to discriminate a benign (calcified) nodule was that it contains CT numbers greater than the CT number of the reference nodule in at least 10% of the nodule’s cross-sectional area.12

Statistical analysis

Separate normal regression models were fitted to the CT numbers for each study. To assess whether the calibration lines differed due to patient∕phantom size (with or without fat rings), a regression model was fitted with the size of the nodule and nodule position as well as nominal nodule calcium content and phantom∕patient size, and their interaction nested within the nodule size and nodule location. Contrasts were estimated for each combination of nodule size and nodule location to test whether the estimated calibration line for nodules scanned in the large phantoms with the fat rings differed significantly from the calibration lines in the small phantoms without the fat rings. This approach is similar to fitting separate regression models to each combination of nodule size and nodule location, including calcium content, patient∕phantom size, and their interaction as predictors. The only difference is that in the former case we use all data to come up with a single estimate of the measurement error, while in the latter, only the data for a particular nodule size and nodule location would be used. Similarly to assess the effect of nodule size on the calibration line, a regression model was fitted with the predictor phantom size and nodule location as well as calcium content, nodule size, and calcium content∗nodule size nested within the phantom size and nodule location. In this model, the product of calcium content and nodule size allowed the effect of calcium content on CT number to be different for different nodule sizes. The SAS system (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. A 0.05 level of significance was used for all significance testing. No multiplicity adjustments were made.

RESULTS

Effect of phantom size

Mean SECT and DECT numbers and slopes and intercepts of the calibration lines for the nodules in the small (no fat ring) and large (with fat ring) thorax sections are listed in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 for each of the conditions in the original experiment and in Table 5 for the repeat experiment. The means in each case are the averages of the CT numbers for each nodule for the three CT scans that were performed under each condition.

Table 1.

Mean CT numbers (HU) and calibration line slopes and intercepts for the 4.8 mm diameter nodules scanned in the middle thorax section both with and without the fat ring. Locations of the individual nodules are shown in Figs. 1a, 1b. Average absolute separations (HU) between the calibration lines with and without the fat rings are listed as are the average underestimates that result when the calibration line for the small middle thorax is employed to estimate the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules in the large middle thorax section. (note that overestimates are negative). Ave. stands for the overall average and St. dev. represents standard deviation. p values are for average absolute separations.

| 4.8 mm nodules | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule position | Small middle thorax section | Large middle thorax section (with fat ring) | Ave. absolute separation (HU) | Ave. underestimate (mg∕cc) | p | ||||||

| CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | ||||

| SECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | −0.8 | 49.9 | 1.01 | −51.5 | −18.8 | 30.6 | 0.99 | −68.1 | 19.3 | 19.0 | <0.001 |

| 2 | −4.6 | 44.4 | 0.98 | −53.6 | −24.9 | 25.4 | 1.00 | −75.1 | 19.0 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| 3 | −10.6 | 46.4 | 1.14 | −67.6 | −24.2 | 29.0 | 1.06 | −77.5 | 17.4 | 15.3 | <0.001 |

| 4 | −1.7 | 45.1 | 0.94 | −48.5 | −11.0 | 28.3 | 0.79 | −50.4 | 16.8 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| 5 | −11.2 | 42.3 | 1.07 | −64.6 | −28.5 | 20.6 | 0.98 | −77.7 | 21.7 | 20.3 | <0.001 |

| Ave. | −5.8 | 45.6 | 1.03 | −57.2 | −21.5 | 26.8 | 0.97 | −69.8 | 18.9 | 18.4 | |

| St. dev. | 4.9 | 2.8 | 0.08 | 8.4 | 6.8 | 3.9 | 0.10 | 11.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| DECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 28.8 | 50.6 | 0.44 | 7.0 | 35.7 | 53.4 | 0.35 | 18.0 | 4.7 | −6.3 | 0.024 |

| 2 | 24.9 | 51.6 | 0.53 | −1.8 | 23.1 | 51.5 | 0.57 | −5.2 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.797 |

| 3 | 27.5 | 48.2 | 0.41 | 6.8 | 18.2 | 43.0 | 0.50 | −6.7 | 5.8 | 12.4 | 0.001 |

| 4 | 27.1 | 52.5 | 0.51 | 1.6 | 25.6 | 51.4 | 0.52 | −0.3 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.800 |

| 5 | 23.1 | 47.9 | 0.50 | −1.6 | 18.4 | 42.7 | 0.49 | −5.9 | 5.1 | 10.4 | 0.036 |

| Ave. | 26.3 | 50.2 | 0.48 | 2.4 | 24.2 | 48.4 | 0.48 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | |

| St. dev. | 2.2 | 2.0 | 0.05 | 4.3 | 7.2 | 5.1 | 0.08 | 10.4 | 2.2 | 7.7 | |

Table 2.

Mean CT numbers (HU) and calibration line slopes and intercepts for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules scanned in the middle thorax section with and without fat rings. Average absolute separations (HU) between the calibration lines with and without the fat rings are listed as are the average underestimates that result when the calibration line for the small middle thorax is employed to estimate the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules in the large middle thorax section [positions: Figs. 1a, 1b].

| 9.5 mm nodules | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule position | Small middle thorax section | Large middle thorax section (with fat ring) | Ave. absolute separation (HU) | Ave. underestimate (mg∕cc) | p | ||||||

| CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | ||||

| SECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 22.6 | 75.1 | 1.05 | −29.9 | 10.3 | 59.5 | 0.98 | −38.9 | 15.7 | 14.9 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 25.1 | 76.7 | 1.03 | −26.6 | 7.2 | 57.5 | 1.01 | −43.0 | 19.2 | 18.6 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 20.4 | 72.7 | 1.05 | −31.9 | 8.2 | 53.7 | 0.91 | −37.3 | 19.0 | 18.2 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 13.5 | 65.6 | 1.04 | −38.6 | 1.3 | 49.2 | 0.96 | −46.7 | 16.4 | 15.7 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 15.2 | 65.2 | 1.00 | −34.8 | −3.7 | 42.9 | 0.93 | −50.3 | 22.2 | 22.2 | <0.001 |

| Ave. (1–5) | 19.3 | 71.1 | 1.03 | −32.4 | 4.7 | 52.6 | 0.96 | −43.2 | 18.5 | 17.9 | |

| St. dev. | 4.9 | 5.4 | 0.02 | 4.6 | 5.7 | 6.7 | 0.04 | 5.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 | |

| 6 | 20.2 | 71.9 | 1.03 | −31.5 | −2.1 | 47.6 | 1.00 | −51.9 | 24.3 | 23.5 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 14.3 | 65.6 | 1.03 | −37.0 | −5.7 | 43.9 | 0.99 | −55.4 | 21.7 | 21.1 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 17.0 | 69.7 | 1.05 | −35.7 | 3.5 | 51.1 | 0.95 | −44.1 | 18.6 | 17.7 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 18.4 | 72.1 | 1.07 | −35.3 | 3.3 | 51.3 | 0.96 | −44.8 | 20.8 | 19.4 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 22.9 | 78.4 | 1.11 | −32.6 | 10.8 | 58.3 | 0.95 | −36.6 | 20.1 | 18.1 | <0.001 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 18.6 | 71.6 | 1.06 | −34.4 | 1.9 | 50.4 | 0.97 | −46.6 | 21.1 | 20.0 | |

| St. dev. | 3.2 | 4.6 | 0.03 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 0.02 | 7.3 | 2.1 | 2.4 | |

| Ave. (1–10) | 19.0 | 71.3 | 1.05 | −33.4 | 3.3 | 51.5 | 0.96 | −44.9 | 19.8 | 18.9 | |

| St. dev. | 3.9 | 4.7 | 0.03 | 3.6 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 0.03 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 2.7 | |

| DECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 23.2 | 48.0 | 0.50 | −1.6 | 25.6 | 45.9 | 0.40 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 0.481 |

| 2 | 24.1 | 48.5 | 0.49 | −0.2 | 20.5 | 44.9 | 0.49 | −4.0 | 3.6 | 7.4 | 0.159 |

| 3 | 22.4 | 46.3 | 0.48 | −1.5 | 19.6 | 40.9 | 0.43 | −1.7 | 5.4 | 11.2 | 0.082 |

| 4 | 22.3 | 47.2 | 0.50 | −2.7 | 17.3 | 42.1 | 0.50 | −7.5 | 5.2 | 10.3 | 0.030 |

| 5 | 22.8 | 47.7 | 0.50 | −2.2 | 16.1 | 43.5 | 0.55 | −11.3 | 4.2 | 8.3 | 0.016 |

| Ave. (1–5) | 22.9 | 47.5 | 0.49 | −1.7 | 19.8 | 43.5 | 0.47 | −3.8 | 4.7 | 8.3 | |

| St. dev. | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 0.06 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 2.7 | |

| 6 | 22.6 | 46.5 | 0.48 | −1.4 | 19.5 | 42.1 | 0.45 | −3.1 | 4.4 | 9.1 | 0.142 |

| 7 | 22.6 | 46.7 | 0.48 | −1.6 | 15.8 | 44.0 | 0.56 | −12.3 | 4.5 | 5.7 | 0.028 |

| 8 | 22.9 | 46.0 | 0.46 | −0.2 | 21.2 | 38.5 | 0.35 | 3.9 | 8.3 | 16.2 | 0.018 |

| 9 | 23.9 | 47.7 | 0.47 | 0.2 | 21.4 | 43.5 | 0.44 | −0.6 | 4.1 | 8.7 | 0.202 |

| 10 | 24.5 | 48.7 | 0.48 | 0.3 | 23.0 | 45.2 | 0.44 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 0.372 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 23.3 | 47.1 | 0.48 | −0.5 | 20.2 | 42.7 | 0.45 | −2.3 | 5.0 | 9.4 | |

| St. dev. | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 0.08 | 6.1 | 1.9 | 4.0 | |

| Ave. (1–10) | 23.1 | 47.3 | 0.48 | −1.1 | 20.0 | 43.1 | 0.46 | −3.0 | 4.8 | 8.8 | |

| St. dev. | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.07 | 5.9 | 1.4 | 3.3 | |

Table 3.

Mean CT numbers (HU) and calibration line slopes and intercepts for the 16 mm diameter nodules scanned in the middle thorax section both with and without the fat ring. Average absolute separations (HU) between the calibration lines with and without the fat rings are listed as are the average underestimates that result when the calibration line for the small middle thorax is employed to estimate the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules in the large middle thorax section [positions: Figs. 1a, 1b].

| 16 mm nodules | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule position | Small middle thorax section | Large middle thorax section (with fat ring) | Ave. absolute separation (HU) | Ave. underestimate (mg∕cc) | p | ||||||

| CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | ||||

| SECT | |||||||||||

| 6 | 25.8 | 81.5 | 1.11 | −29.9 | 9.8 | 62.8 | 1.06 | −43.3 | 18.7 | 16.8 | <0.001 |

| 7 | 21.2 | 75.5 | 1.08 | −33.0 | 3.1 | 54.2 | 1.02 | −48.0 | 21.3 | 19.6 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 23.7 | 76.9 | 1.06 | −29.4 | 9.1 | 60.8 | 1.03 | −42.6 | 16.1 | 15.2 | <0.001 |

| 9 | 27.1 | 80.4 | 1.07 | −26.3 | 12.1 | 60.7 | 0.97 | −36.6 | 19.7 | 18.5 | <0.001 |

| 10 | 27.4 | 82.7 | 1.11 | −27.9 | 12.0 | 62.4 | 1.01 | −38.3 | 20.3 | 18.4 | <0.001 |

| Ave. | 25.1 | 79.4 | 1.09 | −29.3 | 9.2 | 60.2 | 1.02 | −41.8 | 19.2 | 17.7 | |

| St. dev. | 2.6 | 3.1 | 0.02 | 2.5 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.03 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 | |

| DECT | |||||||||||

| 6 | 21.6 | 45.9 | 0.49 | −2.7 | 17.9 | 41.2 | 0.47 | −5.5 | 4.7 | 9.7 | 0.083 |

| 7 | 19.9 | 44.0 | 0.48 | −4.1 | 15.1 | 37.4 | 0.45 | −7.2 | 6.6 | 13.7 | 0.011 |

| 8 | 20.7 | 44.8 | 0.48 | −3.3 | 18.0 | 40.2 | 0.45 | −4.3 | 4.5 | 9.4 | 0.146 |

| 9 | 21.9 | 45.5 | 0.47 | −1.6 | 18.7 | 40.1 | 0.43 | −2.6 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 0.069 |

| 10 | 21.7 | 45.3 | 0.47 | −1.8 | 16.9 | 40.6 | 0.47 | −6.9 | 4.7 | 9.9 | 0.045 |

| Ave. | 21.2 | 45.1 | 0.48 | −2.7 | 17.3 | 39.9 | 0.45 | −5.3 | 5.2 | 10.8 | |

| St. dev. | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.01 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.02 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 1.8 | |

Table 4.

Mean CT numbers and calibration line slopes and intercepts for the 4.8 and 9.5 mm diameter nodules scanned in the upper thorax section both with and without the fat ring. Average absolute separations (HU) between the calibration lines with and without the fat rings are listed as are the average underestimates that result when the calibration line for the small upper thorax is employed to estimate the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules in the large upper thorax section [positions: Figs. 1c, 1d] (note that overestimates are negative).

| Nodule position | Small middle thorax section | Large middle thorax section (with fat ring) | Ave. absolute separation (HU) | Ave. underestimate (mg∕cc) | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | ||||

| 4.8 mm nodules | |||||||||||

| SECT | |||||||||||

| 6 | 5.5 | 55.1 | 0.99 | −44.1 | −4.8 | 44.3 | 0.98 | −53.9 | 10.8 | 10.9 | <0.001 |

| 7 | −14.2 | 44.8 | 1.18 | −73.2 | −21.8 | 31.3 | 1.06 | −74.9 | 13.5 | 11.4 | <0.001 |

| 8 | −10.2 | 40.8 | 1.02 | −61.2 | −14.4 | 30.9 | 0.90 | −59.6 | 10.0 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| 9 | −3.8 | 44.6 | 0.97 | −52.2 | −9.0 | 34.4 | 0.87 | −52.4 | 10.2 | 10.5 | <0.001 |

| 10 | −4.0 | 42.3 | 0.93 | −50.3 | −12.5 | 32.5 | 0.90 | −57.5 | 9.8 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Ave. (6–10) | −5.3 | 45.5 | 1.02 | −56.2 | −12.5 | 34.7 | 0.94 | −59.7 | 10.9 | 10.6 | |

| St. dev. | 7.5 | 5.6 | 0.10 | 11.3 | 6.3 | 5.5 | 0.08 | 9.0 | 1.5 | 0.6 | |

| DECT | |||||||||||

| 6 | 34.7 | 55.1 | 0.41 | 14.4 | 38.9 | 63.1 | 0.48 | 14.8 | 7.9 | −19.4 | 0.133 |

| 7 | 25.0 | 49.2 | 0.48 | 0.8 | 19.6 | 42.4 | 0.46 | −3.3 | 6.8 | 14.0 | 0.150 |

| 8 | 30.5 | 54.7 | 0.48 | 6.4 | 25.4 | 40.8 | 0.31 | 10.1 | 14.4 | 28.8 | 0.005 |

| 9 | 29.0 | 51.5 | 0.45 | 6.4 | 13.8 | 49.9 | 0.72 | −22.2 | 13.9 | 3.6 | 0.004 |

| 10 | 32.2 | 50.0 | 0.36 | 14.4 | 24.1 | 51.0 | 0.54 | −2.8 | 9.3 | −2.8 | 0.187 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 30.3 | 52.1 | 0.44 | 8.5 | 24.4 | 49.4 | 0.50 | −0.7 | 10.5 | 4.8 | |

| St. dev. | 3.7 | 2.7 | 0.05 | 5.9 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 0.15 | 14.4 | 3.5 | 18.1 | |

| 9.5 mm nodules | |||||||||||

| SECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 26.3 | 75.0 | 0.97 | −22.4 | 15.8 | 61.3 | 0.91 | −29.7 | 13.7 | 14.1 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 21.7 | 70.3 | 0.97 | −26.9 | 11.9 | 57.3 | 0.91 | −33.5 | 13.0 | 13.3 | <0.001 |

| 3 | 7.6 | 59.5 | 1.04 | −44.2 | −0.2 | 46.4 | 0.93 | −46.7 | 13.2 | 12.7 | <0.001 |

| 4 | 17.6 | 71.7 | 1.08 | −36.6 | 11.1 | 58.6 | 0.95 | −36.2 | 13.1 | 12.1 | <0.001 |

| 5 | 15.3 | 62.8 | 0.95 | −32.2 | 6.1 | 50.7 | 0.89 | −38.5 | 12.1 | 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Ave. (1–5) | 17.7 | 67.9 | 1.00 | −32.5 | 9.0 | 54.8 | 0.92 | −36.9 | 13.0 | 13.0 | |

| St. dev. | 6.3 | 5.8 | 0.05 | 7.6 | 5.5 | 5.50 | 0.02 | 5.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| DECT | |||||||||||

| 1 | 24.6 | 48.4 | 0.48 | 0.8 | 28.6 | 44.4 | 0.32 | 12.8 | 8.7 | 8.4 | 0.444 |

| 2 | 27.2 | 47.7 | 0.41 | 6.6 | 23.8 | 43.0 | 0.39 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 11.4 | 0.426 |

| 3 | 18.8 | 44.2 | 0.51 | −6.6 | 20.5 | 41.5 | 0.42 | −0.5 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 0.768 |

| 4 | 25.3 | 47.7 | 0.45 | 2.9 | 21.7 | 43.6 | 0.44 | −0.2 | 4.0 | 9.0 | 0.477 |

| 5 | 18.7 | 45.5 | 0.53 | −8.0 | 18.7 | 40.9 | 0.44 | −3.5 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 0.591 |

| Ave. (1–5) | 22.9 | 46.7 | 0.48 | −0.9 | 22.7 | 42.7 | 0.40 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 8.5 | |

| St. dev. | 3.5 | 1.6 | 0.04 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.05 | 5.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | |

Table 5.

Mean CT numbers and calibration line slopes and intercepts for the repeat study of the 4.8 and 9.5 mm diameter nodules scanned in the upper thorax section both with and without the fat ring. Average absolute separations (HU) between the calibration lines with and without the fat rings are listed as are the average underestimates that result when the calibration line for the small upper thorax is employed to estimate the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules in the large upper thorax section (positions: Fig. 2).

| Nodule position | Small middle thorax section | Large middle thorax section (with fat ring) | Ave. absolute separation (HU) Slope | Ave. underestimate (mg∕cc) Intercept | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number of 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | CT number of 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number 100 mg∕cc (HU) | Slope | Intercept | |||

| 4.8 mm nodules | ||||||||||

| SECT | ||||||||||

| Ave. (1–5) | 30.9 | 83.9 | 1.06 | −22.2 | 21.5 | 74.0 | 1.05 | −31.0 | 10.0 | 9.3 |

| St. dev. | 6.3 | 4.5 | 0.06 | 8.9 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 0.06 | 9.1 | 2.5 | 2.0 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 30.4 | 83.5 | 1.06 | −22.6 | 19.3 | 73.2 | 1.08 | −34.6 | 10.6 | 9.7 |

| St. dev. | 4.6 | 4.5 | 0.03 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 5.6 | 0.07 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 2.1 |

| Ave. (1–10) | 30.7 | 83.7 | 1.06 | −22.4 | 20.4 | 73.6 | 1.06 | −32.8 | 10.3 | 9.5 |

| St. dev. | 5.2 | 4.3 | 0.05 | 6.9 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 0.06 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| DECT | ||||||||||

| Ave. (1–5) | 31.4 | 57.7 | 0.53 | 5.1 | 27.8 | 52.7 | 0.50 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 9.9 |

| St. dev. | 3.1 | 1.0 | 0.07 | 6.4 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 0.05 | 6.1 | 3.7 | 9.1 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 31.8 | 57.3 | 0.51 | 6.3 | 28.8 | 50.3 | 0.43 | 7.4 | 8.6 | 13.3 |

| St. dev. | 1.8 | 4.3 | 0.07 | 3.3 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 0.07 | 6.9 | 5.4 | 10.9 |

| Ave. (1–10) | 31.6 | 57.5 | 0.52 | 5.7 | 28.3 | 51.5 | 0.46 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 11.6 |

| St. dev. | 2.4 | 2.9 | 0.06 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 0.07 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 9.7 |

| 9.5 mm nodules | ||||||||||

| SECT | ||||||||||

| Ave. (1–5) | 42.8 | 94.5 | 1.03 | −8.9 | 33.6 | 83.3 | 1.00 | −16.2 | 11.2 | 10.8 |

| St. dev. | 6.5 | 5.8 | 0.02 | 7.3 | 6.3 | 6.6 | 0.04 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 1.7 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 42.4 | 95.4 | 1.06 | −10.6 | 31.6 | 83.0 | 1.03 | −19.7 | 12.4 | 11.7 |

| St. dev. | 3.5 | 4.1 | 0.03 | 3.8 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 0.04 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Ave. (1–10) | 42.6 | 95.0 | 1.05 | −9.7 | 32.6 | 83.2 | 1.01 | −18.0 | 11.8 | 11.2 |

| St. dev. | 4.9 | 4.8 | 0.03 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 0.04 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| DECT | ||||||||||

| Ave. (1–5) | 28.2 | 52.3 | 0.48 | 4.1 | 27.5 | 48.7 | 0.42 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 7.5 |

| St. dev. | 3.8 | 2.8 | 0.03 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 0.04 | 6.0 | 1.3 | 5.0 |

| Ave. (6–10) | 27.5 | 52.3 | 0.49 | 2.8 | 25.9 | 50.4 | 0.49 | 1.3 | 2.8 | 3.8 |

| St. dev. | 2.8 | 2.4 | 0.01 | 3.3 | 4.8 | 3.0 | 0.03 | 6.5 | 1.4 | 4.6 |

| Ave.(1–10) | 27.9 | 52.3 | 0.49 | 3.4 | 26.7 | 49.5 | 0.46 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 5.7 |

| St. dev. | 3.2 | 2.5 | 0.02 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 0.05 | 6.5 | 1.6 | 4.9 |

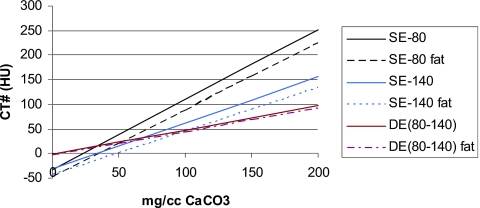

The effect of the patient∕phantom size on the calibration lines obtained for SE at 80 kVp and SE at 140 kVp and DECT for the 9.5 mm nodules in the middle thorax section is illustrated in Fig. 4. Although the SE measurements were made at 80, 120, and 140 kVp, only the SE measurements at 120 kVp are listed in the tables in this paper in order to present a set of data that is representative and not overly excessive. Henceforth, the SE measurements at 120 kVp will be referred to as “SECT” and DE (80–140) kVp CT will be referred to as “DECT.”

Figure 4.

Average calibration lines for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules in the middle thorax phantom with and without the fat rings (large vs small patients) for single energy at 80 kVp, single energy at 140 kVp, and dual energy (80–140 kVp) techniques.

Average absolute separations between calibration lines

The average absolute separations between the calibration lines for the two phantom sizes for a 0–200 mg∕cc CaCO3 range are listed in the tenth column in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Average underestimates of nodule CaCO3 concentrations

The average underestimates that would result from using calibration lines for the small phantom to calculate the CaCO3 of nodules in the large phantom are listed in the 11th column in these tables.

Effect of nodule size

Average absolute separations between calibration lines

Average absolute separations between the calibration lines for nodules of different sizes (e.g., 9.5 mm vs 4.8 mm diameter and 9.5 mm vs 16 mm diameter) are listed in Table 6. Values are listed for both the small and large middle thorax and the small and large upper thorax sections to show the effects of additional beam hardening for large “patients” on the results.

Table 6.

Average absolute separations between the calibration lines derived for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules and the calibration lines for the 4.8 diameter and 16 mm diameter nodules, plus corresponding underestimates (negative) or overestimates (positive) that result when the calibration lines for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules are used to compute the concentrations of the other size 100 mg∕cc nodules. Standard deviations for each set of comparisons are shown in parentheses. Small refers to phantom without fat ring. Large refers to phantom with fat ring. (a) Middle thorax section [Figs. 1a, 1b]. (b) Upper thorax section, repeat study (Fig. 2).

| (a) Middle thorax section [Figs. 1a, 1b] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.5 mm vs 4.8 mm nodules | 9.5 mm vs 16 mm nodules | |||

| Small | Large | Small | Large | |

| Average separation SECT (HU) | 25.4 (4.4) | 25.8 (4.7) | 7.8 (2.2) | 9.8 (3.8) |

| Average separation DECT (HU) | 3.2 (1.8) | 6.1 (2.5) | 2.1 (1.1) | 4.4 (2.5) |

| Average under-∕overestimate SECT (mg∕cc) | −24.6 (4.3) | −26.9 (4.1) | 7.5 (2.3) | 10.0 (3.8) |

| Average under-∕overestimate DECT (mg∕cc) | 5.3 (3.7) | 10.9 (8.9) | −4.3 (2.3) | −5.4 (6.9) |

| (b) Upper thorax section, repeat study (Fig. 2) | ||||

| 9.5 mm vs. 4.8 mm nodules, positions 1–5 | 9.5 mm vs. 4.8 mm nodules, positions 6–10 | |||

| Small | Large | Small | Large | |

| Average separation SECT (HU) | 10.6 (2.7) | 10.4 (1.7) | 11.9 (3.0) | 11.1 (3.4) |

| Average separation DECT (HU) | 6.0 (4.7) | 5.8 (2.5) | 5.3 (4.2) | 5.7 (3.8) |

| Average under-∕overestimate SECT (mg∕cc) | −10.2 (2.7) | −9.3 (2.3) | −11.2 (2.6) | −9.4 (4.7) |

| Average under-∕overestimate DECT (mg∕cc) | 11.2. (6.2) | 9.0 (8.6) | 10.1 (9.3) | −0.6 (12.2) |

Under- and overestimates of nodule CaCO3 concentrations using calibration lines for nodules of a different size

Underestimates (negative) and overestimates (positive) of the nodule concentrations when the calibration lines for the 9.5 mm diameter nodules are utilized to compute the concentrations of nodules of other sizes are also listed in Table 6. For example, when the calibration line for the 9.5 mm nodules is applied to the 4.8 mm nodules, the representative under- or overestimate at a given nodule location was equal to the difference between the CT number of the 4.8 mm, 100 mg∕cc nodule at that location and the corresponding CT number of the 9.5 mm, 100 mg∕cc nodule divided by the slope of the 9.5 mm calibration line at that location.

Effect of nodule position

Average absolute separations between calibration lines

Table 7 summarizes the average absolute separations between average calibration lines for nodules located at inner or central lung positions and nodules located at outer nodule positions. Values in this table are for 9.5 mm diameter nodules scanned in the first study within the central thorax section [Figs. 1a, 1b] and the same nodules scanned within the upper thorax section (Fig. 2) in the repeat study. The inner positions are defined to be positions 5–7 for the first study and positions 5 and 7 for the second. The remaining positions are considered outer except for positions 1 and 6 in the second study where the CT numbers were statistically significantly greater than those at other locations. (For example, in the upper thorax section without fat rings for the second study, the CT numbers of the nodules in positions 1 and 6 were 2–7 standard deviations greater than the mean CT numbers of the nodules in the outer positions and 7–16 standard deviations greater than the mean CT numbers of the nodules at the inner positions.) Nodules at positions 1 and 6 were considered outliers for this comparison. In practice locations 1 and 6 would be grouped together and treated separately from the inner and outer locations for calibration. Table 7 includes separations for both sizes of the thorax sections (with and without the fat rings).

Table 7.

Average absolute separations between the calibration lines derived for 9.5 mm diameter nodules at inner lung locations and the calibration lines derived for 9.5 mm diameter nodules at outer locations and the resulting underestimates (negative) or overestimates (positive) in the computed concentrations of 9.5 mm diameter, 100 mg∕cc nodules at the outer locations when the average calibration lines for the inner locations are employed in the computations. Standard deviations of under-∕overestimates are in parentheses. (a) Middle thorax section [Figs. 1a, 1b]. (b) Upper thorax section, repeat study (Fig. 2).

| Small phantom | Large phantom | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average absolute separation (HU) | Under-∕overestimate at outer locations (mg∕cc) | Average absolute separation (HU) | Under-∕overestimate at outer locations (mg∕cc) | |

| (a) Middle thorax section [Figs. 1a, 1b] | ||||

| SECT | 5.3 | 5.2 (4.3) | 9.5 | 9.8 (4.2) |

| DECT | 0.5 | 1.0 (2.1) | 4.3 | −0.4 (5.1) |

| (b) Upper thorax section, repeat study (Fig. 2) | ||||

| SECT | 4.8 | 4.5 (1.4) | 7.5 | 7.6 (2.3) |

| DECT | 1.9 | 2.0 (3.2) | 4.3 | 8.8 (4.4) |

Average under- or overestimates of nodule CaCO3 concentrations using inner calibration lines to compute concentrations of nodules at outer locations

The average under- or overestimates that result from utilizing the average calibration lines for the inner nodule positions to compute the concentrations of the nodules at the outer locations are listed in columns 3 and 5 of Table 7. The individual over- or underestimates that were used to compute the averages were equal to the difference between the CT number of an outer 100 mg∕cc nodule and the average CT number of the inner 100 mg∕cc nodules divided by the average slope of the calibration line at the inner locations.

Effect of anatomic section

Table 8 details a general comparison of the effects of anatomic section on the measured CT numbers of the nodules. Because the shapes of the lungs and other anatomy are very different for the two sections and the nodule locations are different, we chose to compare the average CT numbers for the five nodules in each lung.

Table 8.

Comparison of CT numbers in upper thorax (small lungs) and middle thorax (large lungs): 9.5 mm nodules; averages for positions 1–5, Tables 2, 4.

| Small phantom | Large phantom (with fat ring) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT number at 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number at 100 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number at 50 mg∕cc (HU) | CT number at 100 mg∕cc (HU) | |

| SECT | ||||

| Large lungs | 19.3 | 71.1 | 4.7 | 52.6 |

| Small lungs | 17.7 | 67.9 | 9.0 | 54.8 |

| Difference (large−small) | 1.6 | 3.2 | −4.3 | −2.2 |

| DECT | ||||

| Large lungs | 22.9 | 47.5 | 19.8 | 43.5 |

| Small lungs | 22.9 | 46.7 | 22.7 | 42.7 |

| Difference (large−small) | 0 | 0.8 | −2.9 | 0.8 |

DISCUSSION

Calibration lines and sensitivity of SE and DE

A review of the slopes of the calibration lines for all of the conditions studied indicates in general that the slopes for SE are all about 1 and the slopes of DE are all about 0.5. The intercepts for SE, however, are quite variable ranging from about −22 to −70 HU. Those for DE are more consistent and within a range of about −5 to 8 HU.

The large offsets in the intercepts for SE are due to errors in the CT numbers of the nodules arising from the very heterogeneous compositions (bone, fat, muscle, lung, air) and shapes of the surrounding thorax sections. The x-ray attenuation properties of these sections are very different from the cylindrical water or uniform plastic phantoms that are employed for the scanner’s beam hardening and scatter corrections. It is interesting to note that the 120 kVp intercept that we measured for the 9.5 mm nodules in the middle thorax section without the fat ring (−33 HU) is nearly identical to the −30 HU intercept that Cann et al.6 measured at 120 kVp for 9.5 mm vials containing various concentrations of diffuse calcification simulating K2HPO4 in water solutions within a chest phantom. The −33 HU intercept for our present study is consistent with the −37 HU intercept calculated for similar conditions in our previous work.5 In that work we also scanned the complete set of nodules at the center of a more homogeneous cylindrical RMI QC phantom, which resulted in SE intercepts (7–13 HU), that were very different from those in the thorax sections, confirming the strong influence of the phantom environment on the measured CT numbers of the nodules.

Like Cann et al., we found a decreased sensitivity [slope (HU∕mg∕cc)] of DE compared to SE. For our study, the decrease was by about a factor of 2 which is similar to the factor of 2.5 found by Cann et al.6 Cann et al. noted that although the error (dispersion about the calibration line) was significantly lower for DE, the reduced sensitivity resulted in a signal-to-noise ratio that was only slightly better for DE. They were able to improve the sensitivity (slope) of DE to almost that of SE by filtering the high energy (e.g., 120 or 140 kVp) x-ray beam with depleted uranium, thereby reducing the overlap between the spectra of the low and high energy x-ray beams.

Effect of phantom size on calibration lines and over-∕underestimates

In general, adding a fat ring to a thorax phantom in our study to increase the phantom size from small to large resulted in a much greater shift in the SECT calibration lines than in the DECT calibration lines.

Middle thorax section

For nodules in the large and small middle thorax section (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4) the overall average absolute separations in HU between the calibration lines were 3.7 (19.2∕5.2) to 5.1 (18.9∕3.7) times greater for SECT than for DECT. Also all of the p values for these separations were significant (<0.05) for SECT, whereas the majority were not for DECT. The overall average underestimates in the concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc CaCO3 nodules when the calibration lines for the nodules in the small thorax are used to estimate the concentrations of those same nodules in the large thorax were also greater for SECT than for DECT. However, (excluding the 4.8 mm DE results which had wide variations) the improvements for DE were about one-half as great as the overall average absolute separations between the calibration lines [e.g., ∼1.6 (17.7∕10.8) to 2.1 (18.9∕8.8) times greater underestimates for SECT than for DECT]. The reason that the improvements in the underestimates in concentration for DE are about one-half of what would be expected based on the shifts in the calibration lines is that the slopes of the DE calibration lines are about one-half the slopes of the SE calibration lines. For example, consider the 9.5 mm diameter nodules in the small and large middle thorax sections (Table 2). The average absolute separations between the calibration lines in the two phantom sizes are 19.8 HU for SECT and 4.8 HU for DECT, which differ by a factor of 4.1. The slopes for the SE calibration lines are about 1.0 and the slopes for DECT are about 0.5, and the average concentration underestimates are 18.9 mg∕cc for SECT and 8.8 mg∕cc for DECT, which differ by a factor of 2.1.

Upper thorax section

For the upper thorax section in the original study (Table 4), the effects of patient∕phantom size on the SECT and DECT calibration line separations and underestimates were considerably less than and in some cases inconsistent with the middle thorax section results discussed above. However, the separations between the calibration lines were still significant for all of the SECT and not for a majority of the DECT. For the 9.5 mm diameter nodules in the upper thorax section, the overall average separation between the calibration lines for the small and large upper thorax phantoms were 2.3 times (13.0∕5.6) greater for SECT than for DECT (vs 4.1 times in the middle thorax), and the average underestimates that result from using the calibration lines for the small phantom to estimate the concentration of the nodules in the large phantom were less for DECT by a factor of 1.5 (13.0∕8.5). For the 4.8 mm nodules, the overall average separations between the calibration lines were nearly the same for SECT (10.9) and DECT (10.5) (vs 5.1 times less for DECT in the middle thorax). The resulting overall average underestimates in the CaCO3 concentration of the 100 mg∕cc nodules were consistent for SECT (10.6±0.6 mg∕cc) but varied widely for DECT, ranging from an underestimate of 28.8 mg∕cc to an overestimate of 19.4 mg∕cc. As indicated above, the worst results for DECT for the upper thorax section prompted us to repeat this part of the experiment. The results of the repeated study were more consistent with the results for the middle thorax section, but they still had the same trends. For the 9.5 mm nodules (Table 5), the overall average separation between the calibration lines for the small and large phantoms was greater for SECT than for DECT by a factor of 3.2 (11.8∕3.7), and the overall average underestimates in CaCO3 concentration were less for DECT than for SECT by a factor of 2.0 (11.2∕5.7). For the 4.8 mm nodules (Table 5) the separations were 1.4 (10.3∕7.2) times greater for SECT than for DECT. The underestimates in the CaCO3 concentration were less variable than in the previous experiment, but they were worse for DECT than for SECT by a factor of 1.2 (11.6∕9.5).

Effect of nodule size

In general, the average absolute separations between the calibration lines for nodules of different sizes at corresponding lung positions were much smaller [by factors of 1.8 (10.6∕6.0) to 7.9 (25.4∕3.2)] for DECT than for SECT for both thorax sections and both phantom sizes (Table 6). Use of the calibration lines for the 9.5 mm nodules to estimate the CaCO3 concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules of other sizes at corresponding lung locations yielded mixed results. For the middle thorax section, the magnitudes of the underestimates or overestimates that resulted were typically less for DECT than for SECT but there were wide variations in the DECT results (standard deviations of ∼7–9) in the large phantom. For the upper thorax section, both with and without the fat ring, the results of using the 9.5 mm calibration lines to estimate the CaCO3 mg∕cc of the 100 mg∕cc 4.8 mm nodules were essentially equally poor (over- or underestimates of about 9–11 mg∕cc) for both SECT and DECT in contrast to the results obtained for the same nodules within the middle thorax section.

Effect of nodule position

With respect to nodule position, the trend that the DECT calibration lines are less dependent upon nodule position is observed. In particular, for three of the four conditions in Table 7, the over- or underestimates of the concentrations of the nodules at the outer locations from computations using the average calibration lines for the inner nodules are smaller for DE than for SE.

Effect of anatomic section

From results shown in Table 8, anatomic section and, in particular, lung size appear to have very little effect (≤4.3 HU) on CT numbers both for SE and DE. This is in contrast to the results of our previous study comparing the CT numbers of nodules in two relatively small air cavities representing lungs within a water equivalent phantom in which case the CT number of a 50 mg∕cc nodule decreased from 37 HU in a 1.8 cm diameter cavity to 19 HU in a 4.4 cm diameter cavity. Thus, the effect appears to be minimal in lung regions of sizes that are more representative of those in the upper and middle regions of the chests of patients. However, the changes may still be significant when comparing the CT numbers in these sections to those in sections where the lungs are very small (e.g., the apices).

Effect of scanner software version

It is interesting to compare the measured CT numbers and computed slopes and intercepts for the nodules in the upper thorax section for the first study (Table 4) to those in the repeat study of the same section (Table 5). Considering positions 6–10 which are essentially identical for the two studies [Figs. 1c, 1d vs Fig. 2] it is observed that, on average, the CT numbers of the 4.8 mm diameter nodules in the second study are about 36 HU greater than those in the first study for SECT. We investigated this further, measuring the mean CT numbers within ROIs manually positioned at identical locations within the heart muscle, fat, muscle, lung, and bone marrow regions on the images of the thorax sections for the two studies. The values for these “tissues” in the two studies were far more similar [typically within about 8 HU or less (13 HU or less for muscle)] than the values for the nodules. The CT number values are tabulated for all kVp in Table 9, below.

Table 9.

Comparison of measured CT numbers of “tissues” in upper thorax phantom for the original (O) and the repeat (R) study. CT numbers for tissues other than the nodules were obtained by manual placement of ROIs in images. CT numbers of nodules represent the averages for the 4.8 mm diameter nodules in positions 6–10 obtained using the automated technique described in Sec. 2C1 (Table 4, 5 for nodules at 120 kVp).

| Tissue | Small upper thorax | Large upper thorax (with fat ring) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | R | O | R | O | R | O | R | O | R | O | R | |

| 80 kVp | 80 kVp | 120 kVp | 120 kVp | 140 kVp | 140 kVp | 80 kVp | 80 kVp | 120 kVp | 120 kVp | 140 kVp | 140 kVp | |

| CT number (HU) | ||||||||||||

| Heart muscle | 69 | 73 | 49 | 52 | 44 | 48 | 66 | 67 | 48 | 48 | 41 | 45 |

| Fat | −111 | −116 | −100 | −100 | −91 | −95 | −97 | −95 | −83 | −84 | −80 | −82 |

| Muscle | 39 | 50 | 20 | 33 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 30 | 19 | 21 | 17 | 17 |

| Lung | −749 | −753 | −751 | −756 | −752 | −757 | −747 | −755 | −749 | −757 | −753 | −756 |

| Bone marrow | 311 | 319 | 255 | 258 | 240 | 243 | 308 | 309 | 247 | 255 | 232 | 237 |

| 4.8 mm, 50 mg∕cc nodule | 19 | 56 | −5 | 30 | −11 | 24. | 5 | 43 | −12 | 19 | −19 | 14 |

| 4.8 mm, 100 mg∕cc nodule | 87 | 130 | 46 | 84 | 35 | 72 | 73 | 111 | 35 | 73 | 23 | 61 |

| Difference (repeat−original) | ||||||||||||

| Heart muscle | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||||||

| Fat | −5 | −1 | −4 | 2 | 0 | −2 | ||||||

| Muscle | 11 | 13 | 9 | 5 | 2 | −1 | ||||||

| Lung | −4 | −5 | −4 | −8 | −8 | −3 | ||||||

| Bone marrow | 8 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| 4.8 mm 50, mg∕cc nodule | 37 | 36 | 35 | 38 | 32 | 34 | ||||||

| 4.8 mm, 100 mg∕cc nodule | 43 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 39 | 37 | ||||||

A possible explanation is that a different scatter correction was applied in the CT reconstruction algorithm in the second study, and this affected mostly the CT numbers of the nodules within the lung region. GE confirmed that there was a different scatter correction for the two studies (software versions for first and second studies were 05MW31.6 and 06MW03.4, respectively) and that this could be a probable explanation for the shift in the CT numbers.14

The consequences of the shifts in the measured CT numbers of the nodules on the estimated CaCO3 concentration of the nodules can be illustrated by computing the CaCO3 concentrations for the 100 mg∕cc, 4.8 mm diameter nodules in the repeat study when using the calibration lines from the original study. For the small upper thorax section (no fat ring), the computed CaCO3 concentrations of the 100 mg∕cc nodules are 137 mg∕cc for SECT and 110.9 mg∕cc for DE. The computed values for the same nodules in the large upper thorax section are 141.4 mg∕cc for SECT and 102 mg∕cc for DE. Thus, the overestimates of the concentrations of the nodules are appreciable for SECT but minor for DE.

Proposed methods for improving calcium estimates

Several techniques could be used to improve the accuracy of the DECT measurements. One would be to filter the high kVp x-ray beam with a high atomic number material, thereby increasing the separation between the low and high energy spectra and independence of the measured low and high energy CT numbers. Cann et al.6 found that this could increase the slope of the DECT calibration line by a factor of 2.4. As long as this change does not significantly increase the separation between the calibration lines for the patient and reference standard phantom situations, the under- or overestimates in computed calcium concentrations would be reduced by about the same 2.4 factor [see Eq. 7]. One manufacturer (Siemens) is utilizing such a filter for DECT acquisitions on their latest dual-source CT scanner. The inaccuracies for the smaller nodules could be decreased by reducing the volume averaging within the nodules. This could be achieved within the scan plane by reconstructing the images to a smaller field size (e.g., the pixel size for the 36 cm field of view is 0.7×0.7 mm2, whereas the pixel size for a 10 cm field of view is 0.2×0.2 mm2). Implementation of better beam hardening and scatter corrections at both energies would improve the CT number accuracy at each energy and would reduce DECT inaccuracies due to factors that do not completely cancel in the dual energy subtraction process. This in turn should improve the material discrimination of DECT (e.g., distinguishing between nodules that have high CT numbers due to calcifications and due to dense fibrous composition). Finally, special filtered backprojection kernels or iterative reconstruction techniques could be used to yield more accurate CT numbers in the central core regions of the nodules.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The DECT lung nodule calcium concentration estimates in our study were in general more accurate and less affected by differences between (a) the calibration phantom size and the patient size, (b) the calibration nodule size and the patient nodule size, (c) the calibration nodule position and the patient nodule position, (d) the calibration phantom anatomy and the patient anatomy, and (e) the software changes in the CT reconstruction. Yet, the DECT estimates were still inaccurate by about 9–11 mg∕cc even in the middle thorax section where the best results were obtained. Also, there were some inconsistencies in which DECT estimates were worse than SECT, especially in the upper thorax section with the smaller 4.8 mm nodules.

Most of the inconsistencies may be due to errors caused by beam hardening, volume averaging, and insufficient sampling. Targeted, higher resolution reconstructions of the smaller nodules, application of high atomic number filters to the high energy x-ray beam for improved spectral separation, and other future developments in DECT may alleviate these problems and further substantiate the superior accuracy of DECT in quantifying the calcium concentrations of lung nodules. Future investigations would be directed toward optimizing the DE technique with respect to radiation dose and accuracy on state-of-the-art rapid kVp switching and dual-source CT scanners, verifying the independence of the optimized DE calibration lines on patient body size, anatomic region, nodule size, and nodule position and incorporating the DE method in a computer-aided diagnosis system for assisting radiologists in differentiation of malignant and benign lung nodules in patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by USPHS Grant No. CA93517. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency and no official endorsement of any equipment and product of any companies mentioned should be inferred.

References

- American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures, 2008 (American Cancer Society, Atlanta, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2003, edited by Ries L. A. G.et al. (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2006) (http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2003). [Google Scholar]

- Webb W. R., “Radiological evaluation of the solitary pulmonary nodule,” AJR, Am. J. Roentgenol. 154, 701–708 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney M. C., Shipley R. T., Corcoran H. L., and Dickson B. A., “CT demonstration of calcification in carcinoma of the lung,” AJR, Am. J. Roentgenol. 154, 255–258 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodsitt M. M., Chan H. P., Way T. W., Larson S. C., Christodoulou E. G., and Kim J., “Accuracy of the CT numbers of simulated lung nodules imaged with multi-detector CT scanners,” Med. Phys. 33, 3006–3017 (2006). 10.1118/1.2219332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cann C. E., Gamsu G., Birnberg F. A., and Webb W. R., “Quantification of calcium in solitary pulmonary nodules using single-energy and dual-energy CT,” Radiology 145, 493–496 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell J. H. and Seltzer S. M., Tables of X-Ray Mass Attenuation Coefficients and Mass-Energy Absorption Coefficients (Version 1.4) (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, 2004) (http://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/Xcom/html/xcom1.html). [Google Scholar]

- Goodsitt M. M., Hoover P., Veldee M. S., and Hsueh S. L., “The composition of bone marrow for a dual-energy QCT technique: A cadaver and computer simulation study,” Invest. Radiol. 29, 695–704 (1994). 10.1097/00004424-199407000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamsu G., Cann C. E., and Nicol R. F., “Calcium quantification in pulmonary nodules using dual energy CT,” Invest. Radiol. 16, 400 (1981). 10.1097/00004424-198109000-00080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla M., Shepard J. O., Nakamura K., and Kazerooni E. A., “Dual kV CT to detect calcification in solitary pulmonary nodule,” J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 19, 44–47 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swensen S. J., Yamashita K., McCollough C. H., Viggiano R. W., Midthun D. E., Patz E. F., Muhm J. R., and Weaver A. L., “Lung nodules: Dual-kilovolt peak analysis with CT-Multicenter study,” Radiolology 214, 81–85 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerhouni E. A. et al. , “CT of the pulmonary nodule: A cooperative study,” Radiology 160, 319–327 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im J. -G., Gamsu G., Gordon D., Stein M. G., Webb W. R., Cann C. E., and Niklason L. T., “CT densitometry of pulmonary nodules in a frozen human thorax,” AJR, Am. J. Roentgenol. 150, 61–66 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth T., Principal Engineer (CT scanners), GE Healthcare (personal communication).