Abstract

Trabecular bone microarchitecture is a significant determinant of the bone’s mechanical properties and is thus of major clinical relevance in predicting fracture risk. The three-dimensional nature of trabecular bone is characterized by parameters describing scale, topology, and orientation of structural elements. However, none of the current methods calculates all three types of parameters simultaneously and in three dimensions. Here the authors present a method that produces a continuous classification of voxels as belonging to platelike or rodlike structures that determines their orientation and estimates their thickness. The method, dubbed local inertial anisotropy (LIA), treats the image as a distribution of mass density and the orientation of trabeculae is determined from a locally calculated tensor of inertia at each voxel. The orientation entropies of rods and plates are introduced, which can provide new information about microarchitecture not captured by existing parameters. The robustness of the method to noise corruption, resolution reduction, and image rotation is demonstrated. Further, the method is compared with established three-dimensional parameters including the structure-model index and topological surface-to-curve ratio. Finally, the method is applied to data acquired in a previous translational pilot study showing that the trabecular bone of untreated hypogonadal men is less platelike than that of their eugonadal peers.

Keywords: trabecular bone, MRI, osteoporosis, structure analysis

INTRODUCTION

Trabecular bone (TB) is an intricate network of bony rods and plates (trabeculae) that is found at the end of long bones, in the ribs, in the vertebra, and in other skeletal sites. Next to bone density, the architecture of TB is the most important characteristic determining the mechanical properties of bone.30, 10 Among architectural parameters the orientation of trabeculae plays a pivotal role as a determinant of local and global stress. Trabeculae follow local stress lines and it has been shown that the stiffness tensor has to be a function of a tensor quantifying the local anisotropy of TB, the fabric tensor.6, 28 The distribution of rods and plates, their number, as well as their orientation also play an important role in determining the mechanical properties of TB.23, 35 Plates are mostly oriented longitudinally, parallel to the local loads they carry, while rods support the plates from buckling and are mostly oriented along the transverse direction, orthogonal to the plates.23In vivo quantification and understanding of the distribution of rods and plates are relevant for both diagnosis and treatment of bone disease since most fractures occur in regions rich in TB, such as the hip, vertebrae, or wrist.39

Trabecular thickness is on the order of 100–150 μm, so high-resolution imaging is needed to resolve TB microarchitecture. Various modalities have been employed to image TB: Ex vivo [images produced by microcomputed tomography (μCT) (Ref. 7) can be easily segmented to provide three-dimensional (3D) information on the trabecular architecture with voxel sizes ≳1 μm] and in vivo [recent advances in micromagnetic resonance imaging (μMRI) (Refs. 40, 22) and high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HR-pQCT) (Refs. 29, 34, 4) have resulted in images with voxel sizes on the order of 100–150 μm allowing 3D trabecular structure to be extracted].

The fabric tensor,11 conceived to reflect the anisotropy of TB, can be estimated by several methods28 such as the mean intercept length (MIL), star-line distribution (SLD), or star-volume distribution (SVD). In MIL, one-dimensional (1D) profiles of a high-resolution 3D TB image are analyzed to determine the mean distance between bone (or marrow) regions based on profile intercepts. A polar plot of the MIL values calculated along different spatial directions reflects the anisotropy of the TB architecture and is fitted to an ellipsoid whose principal axes determine the eigendirections of the fabric tensor. Due to the nature of the MIL method no information is obtained on the type of trabecula in the structure. Other methods, such as the star-volume and spatial-autocorrelation methods,38 also produce estimates of the fabric tensor in alternative ways but still rely on local information to produce a bulk parameter reflecting the mean thickness or spacing of the trabeculae along a given direction.

Other methods exist that provide local information at the level of individual trabecula. Digital-topological analysis (DTA) (Ref. 32) provides a classification of voxels in the skeleton of the TB network into curves, surfaces, junctions, and other secondary types. While DTA determines the type of structure in the network to which a voxel belongs, it requires skeletonization of a binarized image of the TB network, i.e., nontrivial preprocessing of the images. It also does not provide information about the orientation of the structures. Another method of local shape analysis is based on 3D medial axis transformation. It relies on the determination of the topological properties of neighboring voxels within a chosen region, the size of which is a function of the structure’s local thickness.3 Kinney et al.18 decomposed TB images into individual trabecular elements and recorded orientation, mass, and thickness of each element from which orientation distributions were obtained. Liu et al.23 used topological analysis techniques to decompose the TB network into plates and rods along with their specific orientations. Similarly, Stauber and Muller35 introduced a method that produces a local classification of full trabecular elements into rods and plates. In the context of the current discussion, the limitations of this method are the same as those described above for DTA, since DTA is one of its steps. The method of Ref. 35 classifies full trabeculae locally (rather than individual voxels) into platelike and rodlike structures and thus provides different types of classification information about the TB microstructure. Nevertheless, in each of these methods, a “hard” classification is made into either plates or rods and, so far, none of the above methods have been shown to be able of classifying structure on the basis of in vivo images. The tensor scale method introduced by Saha and Wehrli33 alleviates some of the above limitations. Tensor scale does not require skeletonization and provides type and orientation information locally. However, tensor scale currently exists only as a two-dimensional (2D) method, whereby maximal ellipses are fitted into the bone region and their size and orientation are used to determine their in-plane thickness and orientation. Thus, there is currently no method that provides full 3D information on the orientation, thickness, type of trabecular structures, i.e., plates vs. rods, and does so on the basis of grayscale images.

Orientation in digital images can be determined using the structure tensor (Ref. 16, pp. 344) or, equivalently, using the related tensor of inertia (TI), both derived from the image-intensity gradient. The structure tensor has been applied by Niessen et al.27 to single slices of TB images acquired by computed tomography (CT) with voxel sizes of 425×425×1000 and 245×245×500 μm3. Launeau and Robin20 and Launeau19 used the tensor of inertia to quantify the anisotropy of grains by calculating mean tensors of inertia that reflect the mean shape of the grains. While the tensor of inertia has also been used by Ketcham and Ryan17 to quantify the anisotropy of TB, this method has not been applied locally, at the level of individual trabecula, as a means for shape classification.

Here, we have conceived and implemented a method based on the local inertial (LIA) anisotropy of the TB network that produces a continuous classification of image voxels as ones belonging to rodlike or platelike structures (as opposed to a binary differentiation of the two fundamental structure types). We further introduce new classification parameters and entropies that quantify the microstructure of TB both at the local level and in bulk. The 3D orientation and thickness of the trabeculae are also estimated by the method. In LIA, the image intensity, rather than its gradient, is directly treated as a mass density, an analogy to rigid body mechanics well justified for both MR and CT images of TB. The TI is calculated at each point within a ball neighborhood. The eigenvalues of this local TI are then used to classify the voxel and determine the size of the structure to which it belongs while the corresponding eigenvalues are used to determine the orientation of the rodlike or platelike element. LIA can be applied to both grayscale and segmented images, thereby producing a continuous local classification of structures in the image. In this paper, we will first consider the theoretical background of LIA and then describe the methods used to implement it. Since there is no ground truth, a direct validation is not possible. However, we present applications to high-resolution micro-CT images and compare the derived LIA parameters to related architectural measures, i.e., the topological surface-to-curve ratio32 and structure-model index (SMI).14 Lastly, we demonstrate the method’s applicability to grayscale MR images from a pilot study comparing LIA parameters in men with hypogonadism to their healthy peers.

THEORY

To discuss LIA in general we will assume that we are given a function that reflects the bone-volume fraction at each point . We introduce the local TI,

| (1) |

with taking values over the ball S of radius s [Fig. 1a] and is the diad formed by the vector where are the unit vectors defining the coordinate system. The above definition has only one free parameter, the radius of the neighborhood over which is calculated, which will influence the classification of each voxel. The choice of s for the case of TB is discussed in Sec. 3. It is also worth noting that Eq. 1 is a convolution of the density with the tensor kernel , a fact that can be useful when calculating for large values of the scale parameter s. For small values of s, a straightforward local calculation is faster than the Fourier method.

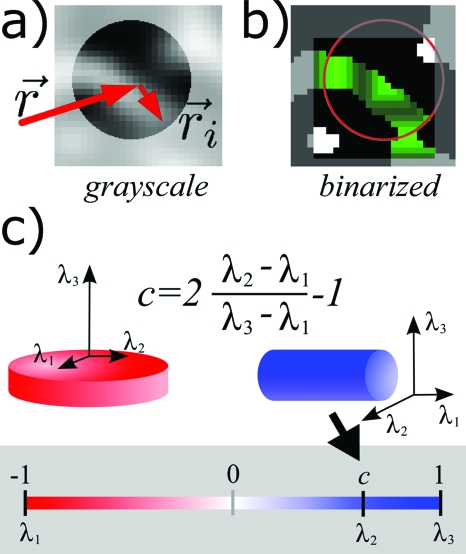

Figure 1.

(a) Ball neighborhood over which the local TI is calculated for the voxel at point . (b) The ball neighborhood that would be used in the grayscale algorithm, marked in green, and the corresponding connected component that would be used in the algorithm version for segmented images, marked in red. (c) A plate/rod, left/right, and its corresponding eigenvectors and eigenvalues. The color scale at the bottom maps values of the classification parameter c to red for voxels belonging to platelike structures [c<0⇔λ2<(λ3−λ1)∕2] and to blue for voxels belonging to rodlike structures [c>0⇔λ2>(λ3−λ1)∕2].

Definition of object classification

To avoid repeated use of the arguments and s, without loss of generality, we will assume that they are fixed and will omit them. Let us denote by , , and the eigenvectors of and let λ1<λ2<λ3 be the corresponding positive eigenvalues. If has two “small” and one “large” eigenvalues, i.e., the middle eigenvalue λ2 is closer to the smallest eigenvalue λ1, the object is oblate (platelike). If the middle eigenvalue is closer to the largest eigenvalue λ3, the object is elongated (rodlike), having two large and one small eigenvalues. Following this argument we introduce the class of an object as

| (2) |

with c taking values from the interval [−1,1]. The parameter c is the position of the middle eigenvalue in the interval between the largest or smallest eigenvalue measured relative to length of that interval. So c=0 corresponds to the middle eigenvalue being at the exact middle (mean) between λ1 and λ3. Its extreme values correspond to the two (out of three) cases of degeneracy of : λ1=λ2⇒c=−1 corresponding to a perfect plate and λ2=λ3⇒c=1 corresponding to a perfect rod. In the case of platelike structures, c<0, the eigenvector belonging to the largest eigenvalue λ3 is perpendicular to the plane defining the plate and will be used to define the orientation of the object. The orientation of rodlike structures is defined by that is parallel to the axis of the rod which is the axis that has the smallest moment of inertia, λ1. Figure 1c illustrates the above definition of plate∕rod classification of voxels.

The third case of degeneracy, when is isotropic and λ1=λ2=λ3, is more interesting since c(λ1,λ2,λ3) has a somewhat nontrivial behavior in this limit. Since this case corresponds to a sphere, a natural value for c would be zero, neither a rod nor a plate. However, since the denominator in the definition of c is zero when λ1=λ3, we have to take the limit of c as the denominator goes to zero. We fix the value of λ1 and let λ3→λ1 with λ2=f(λ3)<λ3, where f(x) is an arbitrary function that satisfies the conditions λ1≤f(x)≤x and f(λ1)=λ1. It is straightforward to show that the limit of c when λ3→λ1 is

| (3) |

We see that only for functions for which ∂f∕∂x=1∕2 at x=λ1 do we get the desired limit of c→0. These functions have the form

| (4) |

i.e., λ2 behaves as the mean of λ1 and λ3 as the object becomes more isotropic. This shows that the definition of c is heuristically satisfactory, since when the eigenvalues are equally spaced we cannot intuitively ascribe platelikeness or rodlikeness to the object according to its moments of inertia. If ∂f∕∂x≠1∕2 at x=λ1 objects that were platelike or rodlike retain this distinction even as they become isotropic, reflecting the sensitivity of c to retain the classification of nearly isotropic objects. Unfortunately, in practice, where one deals with noisy images, this behavior of c can lead to a noisy classification of nearly isotropic objects as discussed in more detail in Sec. 4A. However, nearly isotropic structures (∣c∣⪡1) will contribute less than strongly platelike or rodlike structures (∣c∣≈1) to the parameters we will define in Sec. 2D.

Figure 2 shows three homogeneous ellipsoids whose axes have been chosen to produce TI eigenvalues (λ1,λ2,λ3) of (a) (4, 4.3, 8), (b) (4, 5, 6), and (c) (2, 7.8, 8). Ellipsoid (b) is classified as neither rodlike nor platelike, which is intuitively satisfactory from its visually indeterminate shape. However, if the lengths of the axes of the ellipsoid were equally spaced with the length of the middle axis being the mean of the lengths of the smallest and largest axes, the shape of the ellipsoid is visually indeterminate as before, but the classification c is not zero. To further illustrate the above point and provide the reader with a better intuition of c, we consider the classification of an ellipsoid of homogeneous density with axes lengths a1≥a2≥a3. The eigenvectors of are parallel to the axis of the ellipsoid and the corresponding eigenvalues are

| (5) |

where M is the mass of the ellipsoid. We see from Eq. 5 that equidistributed lengths of ellipsoid axes do not correspond to equidistributed moments of inertia. The classification c is relative to the moment of inertia (local inertial anisotropy) which does not assume a particular shape of the object, such as an ellipsoid. The definition of c is thus more general since is determined by the spatial distribution of the density which is only restricted to be positive but can otherwise be an arbitrary function. We should note that in the special case of homogeneous objects the geometry does fully determine . However, this relationship between geometry and for homogeneous objects is not unique since differently shaped objects with the same are easy to find. For example, one can construct homogeneous cylinders, one with a circular and one with a square basis, that have the same and are thus classified the same by LIA.

Figure 2.

(a) A platelike ellipsoid. (b) An ellipsoid that is neither platelike nor rodlike according to the parameter c with principal moments of inertia of 4, 5, and 6 in arbitrary units. (c) A rodlike ellipsoid.

However, c has an important property that is dependent on the symmetry of the object. Let us consider an ellipsoid that has an axis of rotational symmetry. This ellipsoid has two axes of equal and fixed lengths a and a third axis of length b which we will vary. If we calculate the moments of inertia of such an ellipsoid we see that c is exactly 1 for all values of b>a, i.e., all rods with this symmetry, and exactly −1 for all values of b<a, i.e., all plates with this symmetry. For all axially symmetric objects, c reflects either perfect rodlikeness or perfect platelikeness regardless of their spatial extent, i.e., both a “stubby” and a very elongated rod are perfect rods as long as they are axially symmetric. The same holds for plates. This means that the decrease in rodlikeness or platelikeness for 0<∣c∣<1 reflects the lack of symmetry of the object.

Thickness estimate

While LIA does not provide a direct thickness measure in certain cases we can estimate thickness from the TI. If the neighborhood S contains only a single trabecula, we can consider an ellipsoid into which the mass of that trabecula is redistributed such that this ellipsoid has the same TI as the trabecula. Such an ellipsoid will have the same eigendirections as the TI and the length of its axes can be expressed using Eq. 5 as

| (6) |

In the case of a rodlike structure, we can estimate its thickness as the mean value of a2 and a3, the shortest axes of the ellipsoid. For platelike structures a3, the length of the shortest axis, gives an estimate of the plate thickness.

Robustness of classification

The linearity of with respect to the density results in some desirable properties. A linear transformation of the density, , results in that is scaled and with an added isotropic part,

| (7) |

| (8) |

where we have substituted for in Eq. 1 and explicitly evaluated the integral of the tensor by integrating over a sphere of radius s. We should note that the above result depends on the spherical shape of the neighborhood S and the fact that we are exactly evaluating the integrals. In practice, the integrals are replaced by sums and the above result is only approximate. Since c(λ1,λ2,λ3) is invariant under linear transformations of the eigenvalues, we see that the classification is invariant under arbitrary linear transformations of the density , i.e., scaling and shifting of the image intensity.

A similar analysis can be applied to the effects of noise on if we set α=1 and replace β in Eq. 7 with a random variable . The ensemble averaged TI of the noisy density, , is then

| (9) |

This means that the classification is unbiased by noise, i.e., it averages to its true value since it is unaffected by the isotropic term introduced by noise.

Definition of parameters

In further discussion, we will replace integrals with sums, since in practice we always work with discrete sets of voxels. Two fundamental parameters that result from LIA are the classification of each voxel,

| (10) |

and the orientation of the corresponding element,

| (11) |

Several other parameters can then be derived from these two, treating the initial density as a probability that an element of the architecture is found at . We can define the mean platelikeness P and rodlikeness R of plates and rods by

| (12) |

where V is the volume of analyzed voxels. Another relevant parameter is the plate-to-rod ratio η=P∕R.

Two functions that can be calculated from LIA classification are the spatial probability distribution of rods, , and plates, , where is a unit vector defining a direction, while and are the probabilities for a rod or a plate, respectively, to be oriented along that direction. These probabilities can be calculated as

| (13) |

| (14) |

where we have weighted each occurrence of a rod∕plate oriented along by its classification and the image intensity. The vectors belongs to a discrete set defined below and ≈ denotes this discretization. By convention, we choose that the orientation vectors always point in the upper half-space. To complete the above definition we have to select a way to discretize the space of directions . We parametrize the vectors on the upper unit sphere by their spherical coordinates θ and ϕ, the azimuthal and polar angles, respectively. We map those unit vectors onto a discretized unit disk such that their discrete Cartesian coordinates become

| (15) |

where N is the number of bins along the radial direction when it is oriented along the x or y axes and [⋯] denotes rounding to the integer with the smallest absolute value. In this work, N values of 16, 16, 32, and 64 have been used for data sets of matrix sizes of 323, 643, 1283, and 2563, respectively. While this discretization is slightly anisotropic it gives approximately equal weight to all pairs of θ and ϕ. The probabilities pr and pp are calculated by examining the classification and orientation of each voxel and adding a weighted count, as defined in Eq. 14, to the bin determined by Eq. 15 with θ and ϕ corresponding to the orientation vectors of the voxel. The entropies thus depend on the parameter N which, for each matrix size of the image and type of structure, has to be chosen small enough such that the count in the bin with maximum probability is much larger than 1.

Both probability distributions have the corresponding entropies

| (16) |

| (17) |

where Er and Ep are the rod- and plate-orientation entropies, respectively. Note that these two new parameters that describe TB microarchitecture depend on the capability of LIA to simultaneously determine both the type of trabecula (rod vs plate) and its orientation.

In analogy with the MIL (Ref. 28) and ACF (Ref. 38) methods we can also quantify the mean rod, , and plate, , thicknesses along a given direction,

| (18) |

| (19) |

as the weighted means of the thickness estimates for rods and plates oriented along . Since thickness anisotropy estimated by MIL or ACF is usually represented by functions of the spatial orientation that correspond to ellipsoids, it is important to note that this is not the case with and . Both MIL and ACF produce an estimate of the mean thickness of intersections between sample lines (parallel to ) and the TB architecture. These sample lines intersect both rodlike and platelike trabeculae. Also, their orientation is only seldom parallel to the axis of the rodlike trabeculae or the plane of the platelike trabeculae. As a result of this broad averaging over trabeculae and sampling orientations (relative to the orientation of the trabeculae), the distribution of mean thickness produced by MIL and ACF is a smooth, approximately ellipsoidal function of the spatial direction. In contrast, the mean thickness estimate from LIA captures the variations in orientation present in the TB architecture, since the averaging is effectively performed over an individual trabecula rather than sample lines oblivious to the underlying structure. Also, two separate mean thickness functions are produced, one for each type of trabecula. The LIA estimate of thickness anisotropy retains information about the microstructure of TB that potentially allows distinction of healthy from diseased bone, considering that trabecular thinning in osteoporotic bone loss has been shown to be anisotropic.5

METHODS

LIA was implemented as a C++ program integrated into a Qt (Trolltech ASA, Oslo, Norway) based, cross-platform graphical user interface (GUI). A GUI was necessitated by the complex nature of 3D orientation and classification data. Two variations of the above described algorithm were implemented: One intended for grayscale images and one intended for images segmented into background and a grayscale structure.

Algorithm for grayscale images

While not necessarily restricted to this application, the proposed method was developed for the analysis of TB microarchitecture extracted from high-resolution MR images. Protons in bone have a very short (200 μs) transverse relaxation time so no signal can be detected from bone in conventional imaging. Instead, the fatty marrow is excited resulting in a “negative” image of the trabecular network, with voxel intensities proportional to their bone-marrow fraction.24 Before such images are processed using LIA, coil shading effects have to be corrected and the images have to be inverted and scaled.

Coil shading was removed using a local thresholding algorithm36 that was previously used to calculate bone-volume fraction maps from high-resolution MR images. This algorithm produces an estimate of the local marrow intensity and was modified to locally scale the image by dividing the image intensity with the marrow intensity, without any thresholding. The variation in signal intensity produced by inhomogeneous sensitivity of the receive coil was thus removed, and we will denote the deshaded image by .

Since the image intensity is used in LIA as a weight when calculating means and probability distributions, we have to invert the intensity scale such that high values correspond to the structure we are analyzing while low values correspond to the surroundings of that structure that we want to ignore. The high-intensity values of this inverted image are proportional to the bone-volume fraction of the voxel, in keeping with the mechanical analogy described in Sec. 2. The image that was finally processed by LIA was thus

| (20) |

The structure of an individual trabecula is poorly sampled even in images with the highest possible resolution attainable with state of the art clinical MR imaging.1, 9 The value of s has to be chosen to be less than the intertrabecular spacing to minimize the inclusion of different trabeculae in the same neighborhood but larger than the trabecular thickness, such that a sufficient volume of a trabecula is captured within the neighborhood for its geometry to be properly classified. The desired neighborhood size s is thus on the order of a few voxels. A consequence of this fact is that the shape of the spherical neighborhood is poorly sampled and can bias the determination of the local anisotropy for small sizes of the neighborhood. To alleviate this effect the density was weighted by a Gaussian with standard deviation 2s,

| (21) |

Since the weighting Gaussian was truncated at , its values were scaled to sum up to 1 within the ball , as represented by the normalizing constant cn. The TI [Eq. 21] was then analyzed as described in Sec. 2.

Algorithm for segmented images

In the case of images that are segmented into trabecular structure and background, one can take advantage of the information carried by the segmentation to produce a classification closer to the one intuitively expected. In the grayscale variant of LIA, reflects the properties of the neighborhood regardless of the connectivity of the elements contained within it. For example, two disconnected but nearby trabeculae could be captured within the same neighborhood S and influence the classification of voxels in both trabeculae, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Ideally, one would only want to consider the trabecula to which the voxel “belongs.” Also, as the center of the neighborhood moves over the edge of a trabecula, the voxel classification is affected by the position of its corresponding trabecula within the neighborhood producing edge artifacts. While from the image processing point of view, these effects are undesirable, one has to keep in mind that carries valid physical information about the TB network and describes its mechanical properties. These unwanted effects in grayscale LIA are the price we have to pay when we give up segmentation. However, due to the noise averaging advantages of the grayscale variant of LIA and the physical meaningfulness of , the parameters resulting from the grayscale calculation still have the potential to be highly relevant in the quantification of TB architecture, as we will show later on.

For high-resolution and high-SNR images that are easily segmented, such as the ones produced by micro-CT, LIA can be modified to calculate only using voxels belonging to a connected neighborhood of bone voxels. If is a marrow (background) voxel, is set to 0. If is a bone voxel the calculation of is modified in the following way. Instead of taking into account all voxels in the ball of radius s centered at r [marked in red in Fig. 1b], a region growing algorithm is first employed to select a set of mutually connected voxels starting with the one at similar to the algorithm in Ref. 3. The starting voxel is first marked [bright green in Fig. 1b] as belonging to this set and then each one of its 26 nearest neighbors is marked as belonging to the connected component if it is a bone containing voxel [a darker shade of green in Fig. 1b]. The same procedure is then applied to each of the newly added nearest neighbors resulting in layers of mutually connected voxels being added in each iteration as shown by different shades of green in Fig. 1b. The region growing stops when the addition of new voxels increases the linear size of the connected component beyond s along any of the three orthogonal dimensions. This procedure thus selects the maximal connected component of the voxel that can fit within a cube of sides s, see Fig. 1b. The local TI is then calculated as

| (22) |

where is the center of mass of relative to ,

| (23) |

The same analysis as before is then applied to .

Evaluation of the method

The performance of LIA was evaluated on micro-CT images of human TB of the distal radius from eight donors scanned with a voxel size of (16 μm)3. The images were first binarized by simple thresholding, with the threshold set at the mean of the two intensities corresponding to the maxima of the bimodal intensity histogram. Validation images were then generated by subjecting these binarized images to various processing steps as described below. The images were downsampled by low-pass filtering with a boxcar function in k space, analogous to acquisitions of low-resolution MR data. This type of downsampling is more realistic than, for example, simple averaging over voxels since it reflects the sinc interpolation and Gibbs ringing present in MR images.

Sensitivity to SNR

The sensitivity of LIA parameters to noise corruption of the image was tested by downsampling the high-resolution binarized images to a voxel size of (128 μm)3, more characteristic of images acquired in vivo, and then introducing various levels of noise. Gaussian noise was added to each complex, downsampled image, and the final image was obtained by taking the absolute value of the noise corrupted image. The noisy images were then processed with the grayscale version of LIA. For each noise level, i.e., standard deviation of the noise, eight different noise distributions were used to generate a corrupted image. For each parameter its mean value over the eight images was used as representative for a given SNR. The standard deviation was used as measure of the error in that parameter due to noise at a fixed SNR.

Sensitivity to resolution

Each of the eight micro-CT images was downsampled to have voxel sizes of (16 μm)3, (32 μm)3, (64 μm)3, and (128 μm)3, with the ball neighborhood at each resolution having a radius s of eight, four, two, and two voxels, respectively. The grayscale LIA algorithm was then applied to each of the downsampled images with the scale parameter s adjusted to the increasing voxel size as described above. For each resolution, the parameter values were normalized to their mean value across specimens which varies significantly with resolution. In this manner, the change in parameter differences between specimens is emphasized since we want to know how resolution influences the ability of the algorithm to distinguish structures.

Sensitivity to rotation

Since LIA is applied to discretely sampled images, the orientation of the imaged object relative to the sampling grid could influence the calculated parameters. To test the effects of sample orientation on LIA parameters a single micro-CT image was rotated around its z axis through 5°, 15°, 25°, 35°, and 45°. Each rotated high-resolution image was then downsampled, using the k-space method described above, to voxel sizes of (32 μm)3, (64 μm)3, and (128 μm)3. The grayscale variant of LIA was then applied to all of the downsampled images. Additionally, to test the effect of rotation on interpolated images, the (128 μm)3 voxel size images were sinc interpolated in 3D to (32 μm)3 voxel size and LIA was applied.

Sensitivity to neighborhood size

In order to assess the effect of neighborhood size (s) for LIA classification, the distal tibia of a volunteer was scanned by MRI at 3 T (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) at 160×160×160 μm3 voxel size (acquisition time of 26 min) using a variant of the 3D FLASE pulse sequence.24 A local thresholding algorithm was first used to remove coil shading and normalize the image intensity producing a bone-volume-fraction map.36 The resulting data set was then sinc interpolated to decrease the voxel size to 80×80×80 μm3. Subsequently, the LIA algorithm was applied with s ranging from 160 to 640 μm to determine the optimal value for s.37

Application to in vivo MR images

Finally, LIA was applied to in vivo data acquired as part of a previous study2 in which the effects of testosterone deficiency on TB structure in hypogonadal men were investigated. In that work, the distal tibia of ten untreated hypogonadal subjects and ten eugonadal controls had been imaged using the FLASE pulse sequence24 with a voxel size of 137×137×410 μm3. The purpose of the present experiments was to examine whether LIA could distinguish the two groups of subjects previously studied by other methods. Because these images had anisotropic resolution, the grayscale algorithm could not be directly applied to them. The anisotropic resolution produces an inherent bias for both trabecular orientation (along the lower resolution dimension) and trabecular classification (trabeculae are “stretched” and more platelike). To minimize this bias the images were subjected to the virtual bone biopsy cascade of processing steps:25 A local thresholding algorithm was first used to remove coil shading and to normalize the image intensity producing a bone-volume-fraction map.36 Two sets of images were created from these data. The first was sinc interpolated to decrease the voxel size by a factor of 3 in each dimension to 46×46×137 μm3 voxel size and 3D skeleton maps were obtained by thresholding the images at 80% of marrow intensity and extraction of a skeleton by a thinning algorithm.26 The thinning process during skeletonization identifies surfaces and curves and removes some of the bias present in the raw images, thereby allowing LIA to identify plates and rods and their orientation. A second set was created by resampling the same bone-volume-fraction images along the third dimension by a factor of 3 to isotropic voxel size of 137×137×137 μm3. Subsequently, the LIA algorithm was applied to both data sets.

RESULTS

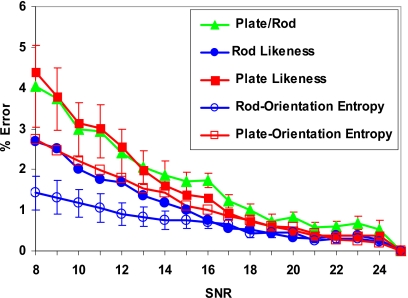

Sensitivity to SNR

Figure 3 shows the percentage error in key LIA parameters relative to high-SNR values (SNR=25) at various noise levels at a given resolution of 128 μm. We notice that, for the SNR regime at which in vivo MR imaging of TB is typically performed (SNR>8), the error due to noise is less than 5% for all the key LIA parameters. These errors are significantly lower than those observed for topological parameters (e.g., surface-to-curve ratio) in a similar SNR regime.21

Figure 3.

Percentage error in key LIA parameters compared to high-SNR values (SNR=25) at various noise levels at constant resolution, (128 μm)3. For clarity, error bars which represent standard error for a fixed SNR are shown only for two parameters.

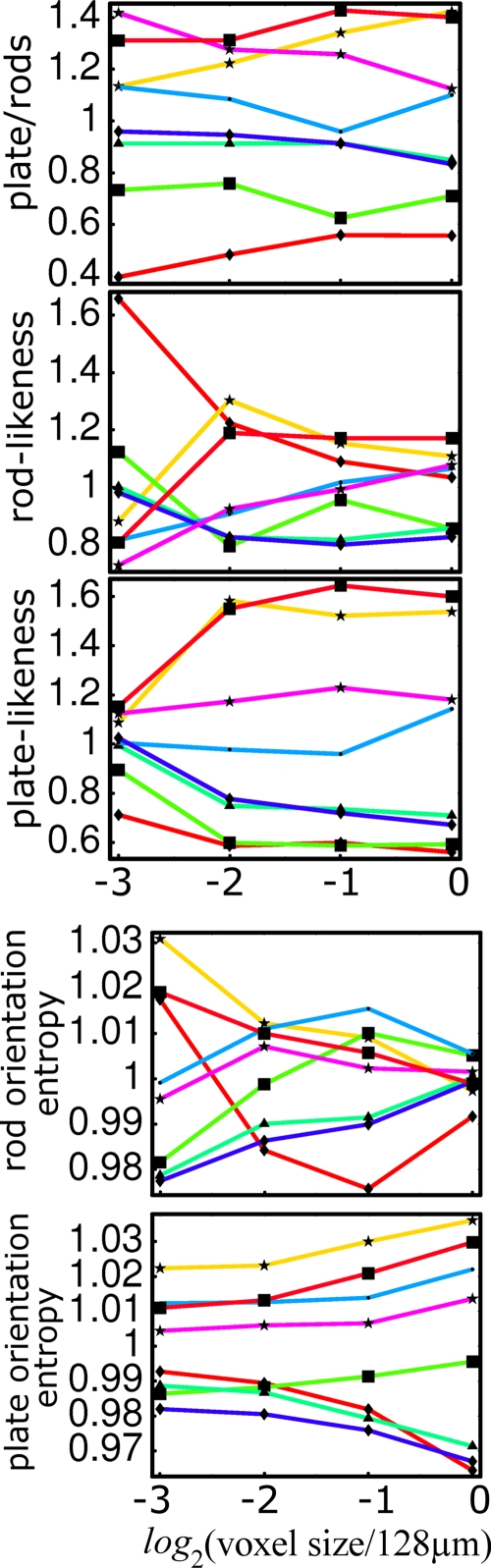

Sensitivity to resolution

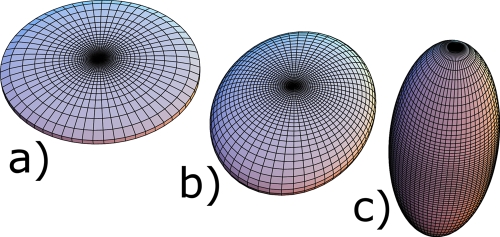

As shown in Fig. 4, the rank of the plate-to-rod ratio among the eight specimens is largely preserved down to the lowest resolution, except for one of the samples. The simple parameters expressing platelikeness and rodlikeness seem to perform less well than the composite plate-to-rod ratio. Figure 5 shows a 3D rendition of the voxels classified as belonging to platelike and rodlike structures in a high-resolution micro-CT data set, in which the continuous classification of voxels is visually evident.

Figure 4.

Dependence on resolution of the plate-to-rod ratio, rodlikeness, platelikeness, rod-orientation entropy, and plate-orientation entropy.

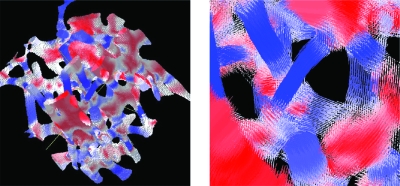

Figure 5.

3D rendition of voxels classified by LIA as belonging to platelike and rodlike structures in a high-resolution micro-CT data set (left panel). The color scale is defined in Fig. 1: Voxels belonging to strongly platelike and rodlike structures are colored in bright red and blue, respectively, while voxels at rod and plate junctions and edges are in light colors. On the right panel, each voxel is replaced by a line parallel to its orientation and centered at the voxel. The lines are color coded in the same way as the solid voxels on the left.

Sensitivity to rotation

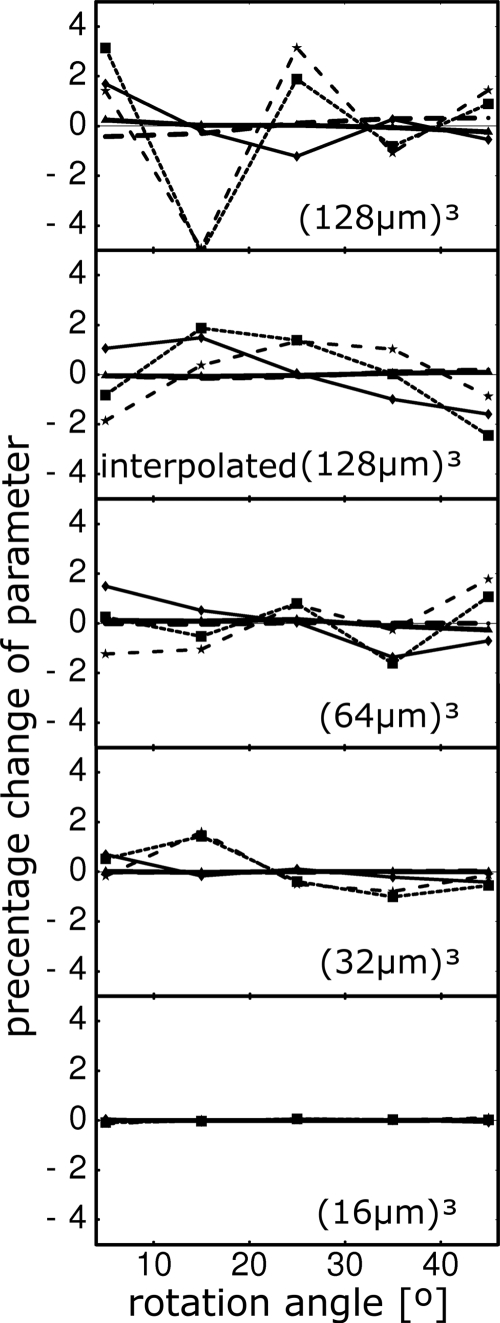

The parameter values resulting from the processing of the rotated images are shown in Fig. 6. Sampling effects are more pronounced at lower resolutions where partial-volume effects are dominant in the sampling of small features such as the trabeculae. As expected, the parameters are almost independent of the rotation angle at the highest resolution with errors increasing as the resolution is decreased. The errors due to rotation can be alleviated if the low-resolution images are sinc interpolated, as shown in the second from the top graph in Fig. 6 for which the lowest resolution image [(128 μm)3 voxel size] was interpolated to a (32 μm)3 voxel size. In all cases errors due to rotation are below 4% and in most cases are less than 2%.

Figure 6.

Percentage change of parameters as a function of the rotation angle of the image at different voxel sizes (resolutions), marked on the graphs. Solid line, plate-to-rod ratio; dashed line, rodlikeness; dotted line, platelikeness; thick solid line, rod-orientation entropy; thick dashed line, plate-orientation entropy. The entropies vary very little with rotation so their curves are close to the x axis and hard to distinguish. The interpolated (128 μm)3 subfigure refers to the data set which was generated by first by downsampling to (128 μm)3 from (16 μm)3 voxel size and sinc interpolating to (32 μm)3 voxel size before rotation.

Sensitivity to neighborhood size

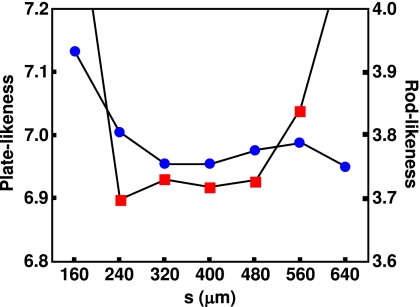

As Fig. 7 shows the mean values for platelikeness and rodlikeness are most stable around s ranging from 320 to 480 μm, approximately corresponding to the mean trabecular spacing. Therefore, for the subsequent LIA analysis of in vivo data, s=410 (corresponding to three voxels) was chosen as the optimal neighborhood size.

Figure 7.

Dependence of LIA parameters (squares: platelikeness; dots: rodlikeness) on neighborhood size based on a 160×160×160 μm3 voxel size in vivo data set of the distal tibia resampled to 80×80×80 μm3 voxel size.

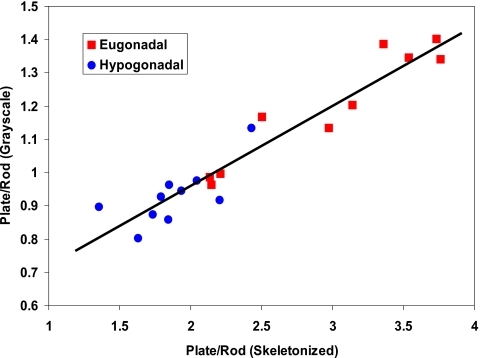

Application to in vivo MR images

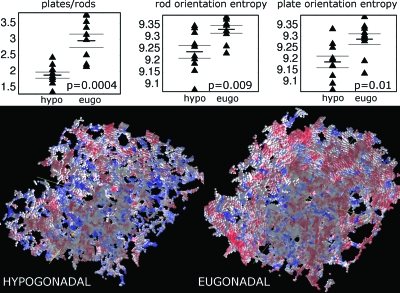

As Fig. 8 shows, the plate-to-rod ratio and the plate- and rod-orientation entropies computed based on skeletonized images are different between the hypogonadal and eugonadal groups. The p values correspond to a two-tailed unpaired t-test and show that all differences are highly statistically significant. The eugonadal group had higher values for the entropies, suggesting that healthy trabecular networks have a more complex structure. The hypogonadal group had a considerably lower plate-to-rod ratio (mean of 1.9±0.1 compared to the one of the eugonadal group, 3.0±0.2). A similar trend was also observed for the LIA parameters computed based on grayscale images at 137×137×137 μm3 voxel size, in which the difference between the two patient groups was highly significant (e.g., p=0.0008 for the plate-to-rod ratio). Further, as Fig. 9 shows, the LIA parameters computed based on grayscale images were highly correlated with those obtained from the skeletonized images even though the range was significantly reduced for the grayscale-derived values. This is due to the fact that the definition of the absolute values of platelikeness and rodlikeness is different in the grayscale version of LIA compared to the segmented version as a result of intensity weighting. For a grayscale in vivo data set at 137×137×137 μm3 voxel size and matrix size 512×384×96, the computational time was around 9 min on a desktop computer with Intel Xeon CPUs.

Figure 8.

Top: Scatter plots of LIA parameters for ten untreated hypogonadal and ten eugonadal subjects. Short horizontal lines mark group means, while longer ones are one standard error away from the mean. p values are shown in the insets for unpaired t-tests of the difference in the means between the two groups. Bottom: 3D renderings of TB skeletons from a hypogonadal and a eugonadal subject. Red voxels belong to platelike regions and blue to rodlike regions. Note the prevalence of plates (red) in the eugonadal subject compared to the hypogonadal subject.

Figure 9.

Correlation between the plate-to-rod ratio calculated from grayscale and skeletonized images for the two patient groups. Solid line is a best fit to the data (R2=0.91).

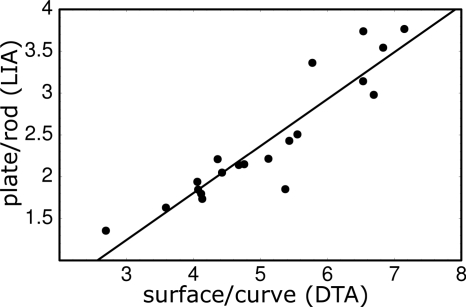

Comparing the LIA analysis to parameters obtained in a previous study,2 we see that the value of the surface-to-curve ratio derived from DTA is different from the LIA plate-to-rod ratio. However, if we compare the ratio of the DTA surface-to-curve parameter between the two groups (1.56) with the ratio of the plate-to-rod parameter between the two groups (1.56) we see that they are identical and reflect the same property of the trabecular network. It is, of course, fortuitous that these two ratios are exactly equal, but as Fig. 10 shows, there is a strong correlation (R2=0.85) between LIA-derived plate-to-rod ratios and DTA-derived surface-to-curve ratio, with a best fit line of slope of 0.56 and intercept of −0.43.

Figure 10.

Correlation of the plate-to-rod ratio, calculated by LIA, versus surface-to-curve ratio, calculated by digital-topological analysis, for the ten images from hypogonadal and ten images from eugonadal men. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was R=0.92 and the best-fit line had a slope of 0.56 and intercept of −0.43.

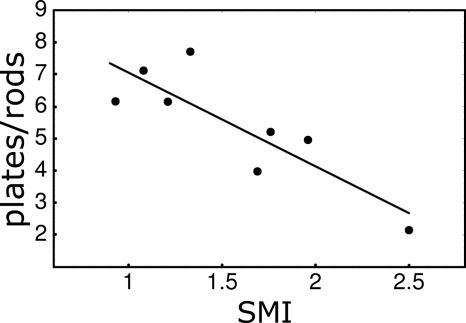

Comparison with conventional measures

We also compared LIA-derived measures with conventional parameters used to characterize TB architecture. Figure 11 shows the correlation between the plate-to-rod ratio (LIA parameter) and SMI for the eight specimens imaged by micro-CT. Both the LIA parameter and SMI were calculated from images that had the same voxel size of (16 μm)3. The correlation coefficient at this resolution (R=−0.85) shows that the plate-to-rod ratio is significantly and inversely correlated with the SMI. This is expected since increasing values of the SMI correspond to increasing rodlikeness of the structure. We then used the values of the SMI calculated at this high resolution as a gold standard and calculated their correlation with the LIA platelikeness vs rodlikeness calculated at progressively larger voxel sizes. The inverse correlation persists to low resolutions with correlation coefficients R=−0.91, R=0.84, and R=−0.76 at voxel sizes of (32 μm)2, (64 μm)2, and (128 μm)2, respectively, showing that LIA calculated parameter accurately reflects the type of trabecular architecture as the resolution is lowered.

Figure 11.

Correlation of the plate-to-rod ratio, calculated by LIA, versus structure-model index for the eight specimens imaged by micro-CT. The correlation coefficient is R=−0.85.

DISCUSSION

Local inertial anisotropy has several advantages over existing algorithms that are aimed at quantifying the microarchitecture of TB:

-

(a)

Local quantification. A standard measure that reflects the prevalence of plates or rods in the trabecular architecture is the SMI introduced by Hildebrand and Rüegsegger.14 While the SMI gives a reliable estimate of the overall prevalence of rodlike or platelike structures, in good agreement with visual presentation (see, for example, Ref. 12), it does not provide local orientation or classification information, while LIA provides both a local estimate of the platelikeness or rodlikeness of the structure and determines the orientation of the elements. Another method by Hildebrand and Rüegsegger,13 based on inscribing maximal spheres into the trabecular network, provides local, 3D information but only about the thickness of the structures. The recently introduced tensor scale method provides very similar information as LIA; however, it currently exists only in its 2D implementation.31

-

(b)

Direct application to grayscale images. The SMI, MIL, SLD, and SVD produce bulk parameters and require binarization of the image. The SMI has been applied in vivo15 but requires a triangulation of the bone surface. Both binarization and triangulation are nontrivial steps, introduce errors that are nonlinear in the noise, and can only be successfully and reliably applied to images of high quality. LIA can be directly applied to grayscale images and is relatively robust to noise in the regime of limited resolution of in vivo imaging.

-

(c)

Three-dimensional orientation information. LIA is currently the only implemented method that determines the 3D orientation of individual trabeculae. Tensor scale,31 which provides orientation information, has currently been implemented only in two dimensions. A geometrical method was used by Gomberg et al.8 to determine the orientation of plates in in vivo images of TB. While this method provides orientation information in 3D, it was explicitly developed for skeletons and can only be applied to surfaces.

-

(d)

New entropy parameters. Because of the 3D-orientation information that LIA provides, we were able to introduce two new parameters: The plate- and rod-orientation entropies, which from our preliminary analysis seem to carry extra information about the microstructure not captured by the standard parameters that rely on the plate-to-rod ratio. Further studies are needed to establish how effective these two new entropy parameters are in clinical data.

It is important to note that in the case of the grayscale version of the algorithm, the thickness estimate represents an apparent thickness since the neighborhood of a voxel might include more than one trabecula. Even though the thickness estimate in that case is not faithful, as it can include information from several trabecula, it is still meaningful since it provides information about the local average mechanical properties of the structure. For the above reasons, one should use caution when interpreting the meaning and numerical values of this estimate.

To extract this wealth of information, LIA poses some requirements on the input images. The algorithm requires an isotropic voxel size since anisotropic voxels introduce bias in both the grayscale and the segmented implementation. While one can account for the anisotropy by properly scaling distances and the size of the neighborhood over which the local TI is calculated, these are usually not sufficient to remedy the problem. The difficulty is mainly due to the fact that the anisotropic voxel size is most often a consequence of the maximum achievable resolution (either due to SNR limits in MRI or dose limits in CT), so the size of the neighborhood over which the TI is calculated is already limited. Reducing its size further to account for an increased size of the voxel along a dimension is either impossible or leads to an unreasonably small neighborhood over which the TI is to be calculated.

One way to overcome this limitation of the algorithm is to reprocess the images, as we did in this work, and apply the segmented version on the binary skeleton of the structure. The increase in resolution by sinc interpolation and the binarization of the structure using skeletonization reduce the effects of the voxel anisotropy on the LIA parameters. Another solution is to resample the input images to isotropic voxel size before applying LIA, as we demonstrated to be feasible in this work. The effectiveness of both approaches is clearly evident from the strong correlation (R2=0.91) of plate-to-rod ratio calculated in the two different ways.

Another obvious and more desirable, albeit much harder to achieve, solution to the problem of anisotropic voxels is the development of protocols to acquire isotropic, high-resolution images in vivo and with sufficient SNR. Current research in the authors’ laboratory is aimed at achieving the goal of producing images more suitable for direct, grayscale analysis by LIA.

CONCLUSIONS

We have developed and implemented a new method to classify voxels of high-resolution TB images into platelike and rodlike structures. The algorithm is based on the notion of a local TI of the image intensity treated as a mass density. The newly introduced classification parameter is real valued, continuous, and invariant under linear transformations of the image. A salient feature of the method is that it captures the intuitive notion of platelikeness and rodlikeness since it is in effect a measure of the degree of axial symmetry. The local orientation of trabeculae is also determined resulting in two new parameters, the rod- and plate-orientation entropies. The method can be applied to both grayscale and segmented images and is relatively robust to noise corruption, resolution reduction, and rotation of images relative to the acquisition grid. LIA is not limited to the analysis of TB and could be applied to any structure where the orientation of elements needs to be determined as well as their rodlikeness or platelikeness. While primarily aimed at the analysis of high-resolution MR images of TB, LIA also shows promise in the analysis of high-resolution micro-CT images of such structures. Not burdened by limitations of noise and voxel size, in micro-CT images LIA has potential to reveal new insight into the fundamentals of the structural changes in TB in metabolic bone disease since it provides detailed information on the orientation of an individual trabecula and allows for their statistical analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeremy Magland for useful discussions during the development of the algorithm. They are also grateful to Dr. X. Edward Guo and Dr. Xiaowei Liu from the Bone Bioengineering Laboratory at Columbia University for calculating the SMI of the specimens imaged with micro-CT.

References

- Banerjee S., Han E. T., Krug R., Newitt D. C., and Majumdar S., “Application of refocused steady-state free-precession methods at 1.5 and 3 T to in-vivo high-resolution MRI of trabecular bone: Simulations and experiments,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 21, 818–825 (2005). 10.1002/jmri.20348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito M., Gomberg B., Wehrli F. W., Weening R. H., Zemel B., Wright A. C., Song H. K., Cucchiara A., and Snyder P. J., “Deterioration of trabecular architecture in hypogonadal men,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 1497–1502 (2003). 10.1210/jc.2002-021429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnassie A., Peyrin F., and Attali D., “A new method for analyzing local shape in three-dimensional images based on medial axis transformation,” IEEE Trans. Syst., Man, Cybern., Part B: Cybern. 33, 700–705 (2003). 10.1109/TSMCB.2003.814298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutroy S., Bouxsein M. L., Munoz F., and Delmas P. D., “In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography,” J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90, 6508–6515 (2005). 10.1210/jc.2005-1258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciarelli T. E., Fyhrie D. P., Schaffler M. B., and Goldstein S. A., “Variations in three-dimensional cancellous bone architecture of the proximal femur in female hip fractures and in controls,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 15, 32–40 (2000). 10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.1.32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin S. C., “Wolff’s law of trabecular architecture at remodeling equilibrium,” J. Biomech. Eng. 108, 83–88 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldkamp L. A., Goldstein S. A., Parfitt A. M., Jesion G., and Kleerekoper M., “The direct examination of three-dimensional bone architecture in vitro by computed tomography,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 4, 3–11 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg B. R., Saha P. K., and Wehrli F. W., “Topology-based orientation analysis of trabecular bone networks,” Med. Phys. 30, 158–168 (2003). 10.1118/1.1527038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomberg B. R., Wehrli F. W., Vasilic B., Weening R. H., Saha P. K., Song H. K., and Wright A. C., “Reproducibility and error sources of micro-MRI-based trabecular bone structural parameters of the distal radius and tibia,” Bone 35, 266–276 (2004). 10.1016/j.bone.2004.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. E. and Kim C. H., “Mechanical consequence of trabecular bone loss and its treatment: A three-dimensional model simulation,” Bone 30, 404–411 (2002). 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00673-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan T. P. and Mann R. W., “Characterization of microstructural anisotropy in orthotropic materials using a second rank tensor,” J. Mater. Sci. 19, 761–767 (1984). 10.1007/BF00540446 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T., Laib A., Muller R., Dequeker J., and Ruegsegger P., “Direct three-dimensional morphometric analysis of human cancellous bone: Microstructural data from spine, femur, iliac crest, and calcaneus,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 14, 1167–1174 (1999). 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T. and Ruegsegger P., “A new method for the model-independent assessment of thickness in three-dimensional images,” J. Microsc. 185, 67–75 (1997). 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1997.1340694.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T. and Ruegsegger P., “Quantification of bone microarchitecture with the structure model index,” Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 1, 15–23 (1997). 10.1080/01495739708936692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Ikeda K., Nishiguchi M., Shindo H., Uetani M., Hosoi T., and Orimo H., “Multi-detector row CT imaging of vertebral microstructure for evaluation of fracture risk,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 1828–1836 (2005). 10.1359/JBMR.050610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahne B., Digital Image Processing, 5th revised and extended ed. (Springer, New York, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Ketcham R. A. and Ryan T. M., “Quantification and visualization of anisotropy in trabecular bone,” J. Microsc. 213, 158–171 (2004). 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2004.01277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney J. H., Stolken J. S., Smith T. S., Ryaby J. T., and Lane N. E., “An orientation distribution function for trabecular bone,” Bone 36, 193–201 (2005). 10.1016/j.bone.2004.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launeau P., “Evidence of magmatic flow by 2-D image analysis of 3-D shape preferred orientation distributions,” Bulletin de la Societé Géologique de France 175, 331–350 (2004). 10.2113/175.4.331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Launeau P. and Robin P. Y. F., “Fabric analysis using the intercept method,” Tectonophysics 267, 91–119 (1996). 10.1016/S0040-1951(96)00091-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Magland J., Rajapakse C. S., Guo E. X., Zhang X. H., and Wehrli F. W., “Implications of resolution and noise for in vivo micro-MRI of trabecular bone,” Med. Phys. 35, 5584–5594 (2008). 10.1118/1.3005598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link T. M., Majumdar S., Grampp S., Guglielmi G., van Kuijk C., Imhof H., Glueer C., and Adams J. E., “Imaging of trabecular bone structure in osteoporosis,” Eur. Radiol. 9, 1781–1788 (1999). 10.1007/s003300050922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. S., Sajda P., Saha P. K., Wehrli F. W., Bevill G., Keaveny T. M., and Guo X. E., “Complete volumetric decomposition of individual trabecular plates and rods and its morphological correlations with anisotropic elastic moduli in human trabecular bone,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 23, 223–235 (2008). 10.1359/jbmr.071009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Wehrli F. W., and Song H. K., “Fast 3D large-angle spin-echo imaging (3D FLASE),” Magn. Reson. Med. 35, 903–910 (1996). 10.1002/mrm.1910350619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magland J. F. and Wehrli F. W., “Trabecular bone structure analysis in the limited spatial resolution regime of in vivo MRI,” Acad. Radiol. 15, 1482–1493 (2008). 10.1016/j.acra.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzanera A., Bernard T. M., Preteux F., and Longuet B., “n-dimensional skeletonization: A unified mathematical framework,” J. Electron. Imaging 11, 25–37 (2002). 10.1117/1.1426080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niessen W. J., Lopez A. M., van Enk W. J., Van Roermund P. M., Romeny B. M. T., and Viergever M. A., “In vivo analysis of trabecular bone architecture,” Inf. Process. Med. Imaging 1230, 435–440 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard A., Kabel J., van Rietbergen B., Dalstra M., and Huiskes R., “Fabric and elastic principal directions of cancellous bone are closely related,” J. Biomech. 30, 487–495 (1997). 10.1016/S0021-9290(96)00177-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pistoia W., van Rietbergen B., Laib A., and Ruegsegger P., “High-resolution three-dimensional-pQCT images can be an adequate basis for in-vivo microFE analysis of bone,” J. Biomech. Eng. 123, 176–183 (2001). 10.1115/1.1352734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs B. L. and L. J.MeltonIII, “Bone turnover matters: The raloxifene treatment paradox of dramatic decreases in vertebral fractures without commensurate increases in bone density,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 11–14 (2002). 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.1.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P. K., “Tensor scale: A local morphometric parameter with applications to computer vision and image processing,” Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 99, 384–413 (2005). 10.1016/j.cviu.2005.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P. L., Gomberg B. R., and Wehrli F. W., “Three-dimensional digital topological characterization of cancellous bone architecture,” Int. J. Imaging Syst. Technol. 11, 81–90 (2000). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P. K. and Wehrli F. W., “A robust method for measuring trabecular bone orientation anisotropy at in vivo resolution using tensor scale,” Pattern Recogn. 37, 1935–44 (2004). 10.1016/j.patcog.2003.12.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sornay-Rendu E., Boutroy S., Munoz F., and Delmas P. D., “Alterations of cortical and trabecular architecture are associated with fractures in postmenopausal women, partially independent of decreased BMD Measured by DXA: The OFELY study,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 22, 425–433 (2007). 10.1359/jbmr.061206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauber M. and Muller R., “Volumetric spatial decomposition of trabecular bone into rods and plates–A new method for local bone morphometry,” Bone 38, 475–484 (2006). 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilic B. and Wehrli F. W., “A novel local thresholding algorithm for trabecular bone volume fraction mapping in the limited spatial resolution regime of in vivo MRI,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 24, 1574–1585 (2005). 10.1109/TMI.2005.859192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilic B., Magland J., Wald M., and Wehrli F. W., “Advantages of isotropic voxel size for classification of trabecular bone struts and plates in micro-MR images,” Proceedings of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance Imaging 16, 3627 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Wald M. J., Vasilic B., Saha P. K., and Wehrli F. W., “Spatial autocorrelation and mean intercept length analysis of trabecular bone anisotropy applied to in vivo magnetic resonance imaging,” Med. Phys. 34, 1110–1120 (2007). 10.1118/1.2437281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli F. W., Gomberg B. R., Saha P. K., Song H. K., Hwang S. N., and Snyder P. J., “Digital topological analysis of in vivo magnetic resonance microimages of trabecular bone reveals structural implications of osteoporosis,” J. Bone Miner. Res. 16, 1520–1531 (2001). 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.8.1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrli F. W., Saha P. K., Gomberg B. R., and Song H. K., “Noninvasive assessment of bone architecture by magnetic resonance micro-imaging-based virtual bone biopsy,” Proc. IEEE 91, 1520–1542 (2003). 10.1109/JPROC.2003.817867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]