Abstract

While high-throughput protein–protein interaction screens were first published approximately 10 years ago, systematic attempts to map interactions among viruses and hosts started only a few years ago. HIV–human interactions dominate host–pathogen interaction databases (with approximately 2000 interactions) despite the fact that probably none of these interactions have been identified in systematic interaction screens. Recently, combinations of protein interaction data with RNAi and other functional genomics data allowed researchers to model more complex interaction networks. The rapid progress in this area promises a flood of new data in the near future, with clinical applications as soon as structural and functional genomics catches up with next-generation sequencing of human variation and structure-based drug design.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, herpes viruses, HIV, mass spectrometry, protein interaction networks, protein purification, RNAi, yeast two-hybrid screens

Host–virus interactions have been studied since the discovery of viruses in 1898, when Martinus Beijerinck described tobacco mosaic virus. However, only with the invention of the electron microscope, protein biochemistry and eventually nucleic acid sequencing has their systematic molecular characterization become possible. Considering their small size, it was no surprise that the first completely sequenced genome was a phage, namely MS2 [1]. To date, more than 5000 viruses have been described [2,101], although many have not been completely sequenced nor classified into any of the major virus families. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome database lists 3398 complete sequences for 2319 viral genomes [102]. In fact, there may be up to a billion virus particles present in a milliliter of seawater, at least in certain areas [3], and most bacteria and higher organisms appear to be infected by phage or other viruses (e.g., [4]). If there are millions of species in our biosphere there is likely to be a similar number of viral species that infect them.

Given their importance for human health, it may come as a surprise that the biology of relatively few viruses has been studied in detail. In particular, a molecular understanding of pathogenesis requires that we know what individual viral proteins do in the cells of their hosts, with whom they interact and what the consequences of these interactions are. While there are thousands of studies of individual viral genes and proteins, this review summarizes our knowledge of virus–host protein–protein interactions and focuses on global attempts to collect and analyze such interactions [5]. ‘Global’ means that (almost) all proteins of a genome are analyzed. This ensures that all proteins receive the same attention, especially in large viral genomes that may encode hundreds of proteins.

Experimental methods to study host–pathogen interactions

In contrast to viruses that enter their host cells completely and must express all their proteins in the host cell, many bacteria inject only a few effector proteins into their host cells. For example, pathogenic Escherichia coli strains such as O157 encode in the order of 50 effector proteins that are injected into host cells [6]. The challenge here is to identify the bacterial effector proteins. For viruses, we can safely assume that all viral proteins enter the cell. Thus, an important goal of virus studies is to analyze the activity of each protein inside the cell. Initially this can be done by analyzing the effect of viruses on host cell gene expression or metabolism. Such studies are beyond the scope of this review and are reviewed in [7,8]. We focus on the direct effects of virus proteins on host proteins by means of direct interaction. While it has become relatively straightforward to identify host–virus protein–protein interactions it remains extremely difficult and time-consuming to find out the exact biological role and the molecular mechanisms of such interactions. Because of such difficulties most studies have focused on single viral proteins and their interactions. This approach is still invaluable for the understanding of a protein of interest but it does not provide a global understanding of virus biology (unless many such datapoints are integrated into global models, see below). For example, despite thousands of publications and many thousand protein–protein interactions of HIV and human proteins, we are still far from a complete understanding of HIV biology. Therefore, any method suitable in molecular biology is required to unravel the intricacies of each infection process. Protein interaction analysis is only one strategy that can be, and needs to be, applied to virus–host interactions. The following paragraphs briefly describe the most important methods for interaction analysis and their advantages and disadvantages.

2D-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis & mass spectrometry-based proteomics

Numerous proteomic studies have been carried out to study the effect of infections on human and other cells, typically using 2D gel electrophoresis of whole-cell lysates taken before and after infection, followed by mass spectrometric (MS) identification of the proteins detected in a gel. Maxwell and Frappier have reviewed proteomic studies of virus infections [9]. These studies give us a sense of the changes in protein expression that are caused by a viral infection and, thus, often hint at regulatory roles of virus proteins. For example, if the level of a host protein increases after infection, this indicates that the virus either enhances its transcription, translation or stability. Obviously, the disadvantage is that such observations do not give us much mechanistic insight into the infection process. In order to study the mechanism of virus infection, we need to find the virus and host proteins that interact with each other and with other components of the cell, such as nucleic acids or even metabolites. While MS is not always the best method to detect direct interactions, especially in complex mixtures, it is invaluable to determine the constituents of such mixtures and, thus, often suggests direct interactions.

Virion purifications & MS screens

Interactions among virus and host proteins can be identified by simply isolating virion particles, as they often incorporate host proteins during assembly. For example, Chertova et al. analyzed HIV-1 virions derived from monocyte-derived macrophages by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), followed by tryptic digestion of proteins in individual gel slices and subsequent MS analysis [10]. They found 253 different human proteins, 33 of which were already known to be virion components. This and other studies are reviewed by Maxwell and Frappier [9] and further summarized in Table 1. As with the studies mentioned above, such proteomics studies have detected many human proteins in virion particles, although it often remains unclear which virus proteins they interact with and whether these interactions are biologically relevant or just contaminations of the virion preparations. Also, note the substantial discrepancies between multiple studies (Table 1). For example, while some studies find only a few host proteins associated with virion particles, others find dozens or hundreds. Obviously further efforts are required to standardize and document detailed purification protocols so that these results become more reproducible.

Table 1.

Selected proteomic analyses of virions and associated host proteins.

| Virus | Host | Virus/host proteins detected | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | Human | 10/15 | [37] |

| HIV-1 | Human | 15*/253 | [10] |

| hCMV | Human | 6/30 | [38] |

| hCMV | Human | 71/71 | [39] |

| mCMV | Mouse | 58/7 | [40] |

| EBV | Human | 35/6+ | [41] |

| KSHV | Human | 24/82 | [42] |

| KSHV | Human | 10/9 | [43] |

| MHV68 | Mouse | 17/74 | [44] |

| Vaccinia IMV | Human | 13/5 | [45] |

| Vaccinia IMV | Human | 63/250 | [46] |

| Vaccinia IMV | Human | 75/23 | [47] |

| WSSV | Shrimp | 18/181 | [48] |

| WSSV | Shrimp | 33/39 | [49] |

| WSSV | Shrimp | 30/180 | [50] |

Numbers that are larger than the number of encoded proteins in a genome derive from fragments or preproteins.

CMV: Cytomegalovirus; IMV: Intracellular mature virions; KSHV: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; MLPV: Myxoma leporipoxvirus; WSSV: White spot syndrome virus.

Adapted from [9].

Protein interaction screens using the yeast two-hybrid system

An important alternative to MS-based proteomics are interaction screens using the yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system and related methods, such as bacterial two-hybrid systems (see [11] for a review on protein interaction methods).

The advantage of the two-hybrid system is that screens can be carried out relatively easily and quickly once bait protein clones and prey libraries are available. The screens are less dependent on the right choice of experimental conditions compared with affinity purification studies, as both bait and prey libraries are usually expressed at similar levels. Although this may give rise to unphysiological levels of protein, elevated expression levels also increase the sensitivity of the Y2H system. Obviously, the physiological significance of each Y2H interaction has to be worked out under conditions reflecting a ‘real’ infection. It has also been suggested that Y2H screens tend to enrich transient interactions (as opposed to affinity purification/MS studies, which tend to enrich stable interactions) [12].

If an interaction cannot be verified under physiological conditions, there are a number of other strategies to validate Y2H interactions. Often interactions are reproduced using different methods, such as co-immunoprecipitations or glutathione-S-transferase pull-downs [11]. In addition, bioinformatic analysis can support Y2H data (e.g., if coexpression can be shown or if the interacting proteins belong to the same functional group, such as transcription factors, or are localized in the same subcellular compartment). Note that computational tools to verify protein–protein interactions are very similar to those used for the prediction of interactions [13].

A major disadvantage of the Y2H system is that it detects only a fraction of all interactions. Recent studies [14,15] have estimated that current Y2H systems detect, on average, only a quarter of all interactions. In other words, this translates to a 75% false-negative rate. Although the Y2H system has often been criticized for producing false positives, it has been shown that proper controls can efficiently prevent false positives and, thus, the quality of large-scale screens is often as good as that of small-scale screens [16].

Intraviral interactomes

Viral proteins are expected to interact not only with host proteins but also with other viral proteins. Therefore, it makes sense to start interaction projects by testing all pairwise interactions among the proteins of a viral genome [17]. In fact, this has been done with a number of viruses and phages (Table 2). It is not surprising that only a fraction of viral proteins are found to interact with each other, indicating that the other ones are interacting with the host. For example, of the 89 EBV proteins, only 27 interact with each other while 40 proteins were found to interact with the host. While certain viral proteins are not necessarily expected to interact with any other protein (such as herpesvirus-encoded ribonucleotide reductases, which interact primarily with their substrates), they often do interact with other proteins [18], both intravirally as well as with the host. It remains to be seen what the physiological role of such interactions is.

Table 2.

Intraviral interactomes.

| Virus | Proteins | Interacting proteins | Interactions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage T7 | 55 | 26 | 25 | [51] |

| EBV | 89 | 27 | 43 | [23] |

| EBV | 89 | 61 | 218 | [24] |

| KSHV | 89 | 50 | 123 | [18] |

| VZV | 69 | 55 | 173 | [18] |

| mCMV | 170 | 111 | 406 | [24] |

| HSV-1 | 95 | 48 | 111 | [24] |

| Vaccinia | 266 | 47 | 37 | [52] |

| HCV | ~10 | 4 | 6 | [21] |

| SSV1 | 34 | 10 | 9 | [Uetz et al., Unpublished Data] |

These studies tested (almost) all viral proteins against each other. Viral interactomes provide the basis for combined virus–host interaction networks as they may include virus proteins not interacting with host host proteins. See text for details.

CMV: Cytomegalovirus; HSV: Herpes simplex virus; KSHV: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; SSV: Sulfolobus shibatae virus; VZV: Varicella zoster virus.

Small-scale host–virus interaction screens

Given the multitude of known viruses, or even human pathogenic viruses, it is surprising that only a few systematic screens for interactions among viral and host proteins have been undertaken. While thousands of host–virus interactions have been collected over the past decade or so, most of them have been found in individual screens and small-scale studies. Per interaction, such data is more valuable than the large-scale screens because single interactions are usually verified and their biological significance evaluated. However, these papers often do not report interactions that have been found in screens but were not further analyzed. In addition, small-scale screens tend to focus on well-known proteins and neglect proteins of unknown significance. At least for some viruses, small-scale screens have accumulated massive amounts of data. This is immedidately evident from the most comprehensively investigated virus, HIV. In order to collect the 2589 unique HIV–human interactions documented in the HIV–human protein interaction database at the NCBI [19], a total of 14,312 references were collated to obtain these interactions and, even more importantly, to validate them and study their biological significance. This is even more striking when the small size of the HIV genome is considered, which encodes only nine proteins. Nevertheless, host–virus interactions of HIV are by far the most numerous with the next best-studied virus, HCV, having accumulated ‘only’ approximately 1200 interactions (Table 3) [20].

Table 3.

Number of protein–protein interactions for selected viruses on VirusHostNet database.

| Organism | Redundant | Nonredundant | Redundancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV | 697 | 461 | 51.2 |

| Human herpesvirus 4 | 573 | 420 | 36.4 |

| HIV | 2299 | 392 | 486.5 |

| Human papillomavirus | 547 | 299 | 82.9 |

| Vaccinia virus | 262 | 232 | 12.9 |

| Adeno-associated virus | 243 | 224 | 8.5 |

| HBV | 154 | 103 | 49.5 |

| Human adenovirus | 188 | 86 | 118.6 |

| Human herpesvirus 1 | 120 | 81 | 48.1 |

| Influenza A virus | 114 | 77 | 48.1 |

| Primate T-lymphotropic virus 1 | 112 | 73 | 53.4 |

| Simian virus (SV5 & SV40) | 89 | 44 | 102.3 |

| Human herpesvirus 5 | 69 | 40 | 72.5 |

| Bovine papillomavirus | 54 | 32 | 68.8 |

| Human herpesvirus 8 | 48 | 32 | 50.0 |

| SARS coronavirus | 37 | 24 | 54.2 |

| Simian immunodeficiency virus | 29 | 19 | 52.6 |

| Dengue virus | 32 | 16 | 100.0 |

| Measles virus | 19 | 14 | 35.7 |

| West Nile virus | 21 | 13 | 61.5 |

| Others | 530 | 340 | 55.9 |

PPI: Protein–protein interaction.

Data taken from [36].

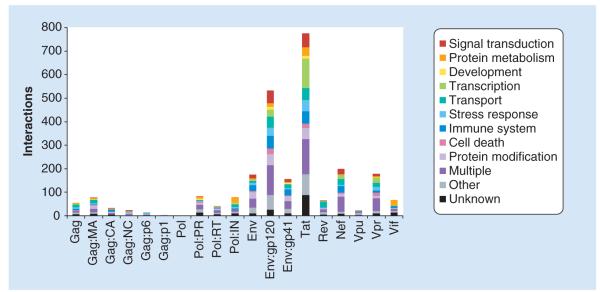

The cumulated dataset for HIV also illustrates the interaction bias for certain proteins (Figure 1): the vast majority of protein–protein interactions is known for Tat (~800 interactions) and for gp120 (~550 interactions), more than for all other proteins combined [19]. It remains unclear why these proteins behave so promiscuously, which fraction of these interactions are really physiologically relevant, and how many are false positives or actually ‘biological false-positives’ (i.e., interactions that can be clearly detected in an experiment but do not have any biological meaning).

Figure 1. Distribution of interactions based on biological process gene ontology terms and individual HIV-1 proteins.

The x-axis shows the individual HIV-1 structural proteins Gag, Pol and Env and their cleavage products, and the regulatory and accessory HIV-1 proteins, Tat, Rev, Nef, Vpu, Vpr and Vif. The y-axis displays the number of interacting human proteins. The various colors represent the biological process categories according to gene ontology terms.

CA: Capsid; IN: Integrase; MA: Matrix; NC: Nucleocapsid; PR: Protease; RT: Reverse transcriptase.

Reproduced with permission from [19].

Systematic Y2H virus–host interaction screens

Surprisingly few attempts have been undertaken to systematically analyze protein–protein interactions of viruses (i.e., the identification of interactions for many or all proteins of a virus). Of the screens that have been published, one important lesson arises quickly: most screens identify only a fraction of all interactions (Table 4). We summarize the published screens and comment on a few ongoing projects below.

Table 4.

Systematic virus–host screens.

| Virus | Host | PPIs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| EBV | Human | 173 | [23] |

| HCV | Human | 314 | [22] |

| Influenza | Human | 135 | [53] |

| VZV | Human | 876 | [Haas et al., Unpublished Data] |

| KSHV | Human | 252 | [Haas et al., Unpublished Data] |

| Dp1 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 38 | [Hauser et al., Unpublished Data] |

| Cp1 | Streptococcus pneumoniae | 11 | [Hauser et al., Unpublished Data] |

This table only lists virus–host screens with all or almost all virus proteins screened against comprehensive human libraries. Note that this approach will usually identify only a fraction of all virus–host interactions (see text for details).

KSHV: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus; PPI: Protein–protein interaction; VZV: Varicella zoster virus.

HCV

HCV was one of the first viruses to have been investigated for both intraviral as well as virus–host interactions. HCV is a particular challenge as this virus encodes a single polyprotein of 3010 amino acids, which are processed into ten mature proteins. Flajolet et al. tested all pairwise combinations of them in Y2H experiments but found only two interactions, of which only the self-interaction of the capsid proteins was reproducible with a second reporter gene (lacZ in addition to His3) [21]. Flajolet et al. explained this disappointing result by the fact that HCV proteins may only interact when refolded during processing in vivo. To circumvent this problem Flajolet et al. then screened random libraries of HCV bait and preys against each other and this approach turned out to be more successful – five interactions were found of which three had not been reported previously.

De Chassey et al. have carried out two independent screens for host–virus interactions, using two human cDNA libraries each [22] resulting in four screens in total. Unfortunately, they did not distinguish between the two libraries but only between protocol (mating vs transformation), so it remains unclear how many interactions they got from each library. In any case, one set of screens (infection mapping [IMAP]-1: mating) resulted in 224 interactions while the other (IMAP-2: transformation) resulted in 112. Surprisingly, only 22 interactions overlapped among the two screens. This demonstrates a general problem of interaction screening by any method – screens are rarely saturated (i.e., no single screen can ever find all interactions).

Note that the problem of polyprotein processing was addressd by de Chassey et al. by splitting up the HCV polyprotein into 27 individual fragments. One of these constructs, NS3, was used successfully by both HCV studies, while another (NS5A) was only used successfully by de Chassey, with no interaction found in Flajolet et al. This may indicate that NS5A does not interact with any other virus protein but only with host proteins.

Epstein–Barr virus

Epstein–Barr virus is a γ-herpesvirus related to Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) and encodes 89 proteins. All proteins were tested in Y2H assays against each other and revealed 43 intraviral interactions [23]. In addition, Calderwood et al. also screened 85 proteins against a human spleen cDNA library, which yielded another 173 interactions between virus and human proteins. The resulting virus–host interaction map contained 40 EBV and 112 human proteins. EBV proteins appear to bind preferentially to highly connected proteins in the human interactome, so-called hubs. This is also shown by the fact that 89 of the 112 EBV-binding human proteins have been found in previous interactome studies. The average degree (i.e., their number of interactions) of EBV-targeted human proteins in the human interactome (15 ± 2) was significantly higher than the average degree of proteins picked randomly from the human interactome (5.9 ± 0.1).

We have also carried out Y2H tests of all EBV proteins against each other and found 213 intraviral interactions [24], although we found only six of the 43 interactions found by Calderwood et al. The fact that both screens were superficially very similar is yet another demonstration that slight differences in Y2H protocols can cause dramatic differences in outcomes [25].

KSHV & varicella-zoster virus

Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) were the first large viruses to be screened systematically for intraviral interactions [18]. While KSHV is a γ-herpesvirus as is EBV, VZV is an α-herpesvirus that causes chickenpox and shingles. The KSHV and VZV screens revealed 123 and 173 intraviral interactions, respectively. In combination with a more recent analysis that added the intraviral interactomes of EBV, mouse cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus-1, our analyses generated a total of 1007 interactions of five human herpesviruses [24]. However, we only screened KSHV and VZV against human libraries, which produced a total of 1128 human–virus interactions [Haas et al., Unpublished Data]. Similar to the findings by Calderwood, both KSHV and VZV also preferentially target highly connected human proteins, in particular proteins involved in splicing and protein degradation. The major challenge for coming years will be the characterization of each interaction and to demonstrate its biological significance.

Bacteriophage

Phages have played a crucial role in the early history of molecular biology and were instrumental to our understanding of basic concepts of genetics, such as mutations, recombination and the gene itself. Thus, it is surprising that no comprehensive analysis of phage–host interactions has been published. We have recently started to systematically investigate interactions between Streptococcus pneumoniae and two of its phages, Cp1 and Dp1 [Hauser et al., Unpublished Data]. These screens were carried out using all 28 and 72 full-length phage open reading frames screened against full-length clones of S. pneumoniae and identified 11 and 38 host–phage interactions, respectively. A more detailed analysis of these interactions will be published in a forthcoming paper.

Protein interaction screens & functional screens: RNAi

The significance of most protein–protein interactions remains unclear until their physiological significance can be shown, often by mutations or other functional experiments. RNAi screens provide such evidence by depleting RNAs of defined genes. Several recent studies have systematically investigated which human genes are required for HIV infection and replication [26,27]. The two studies by Brass and Konig et al. are discussed in more detail by Alec Hirsch in this issue but they are remarkable in our context for two reasons. First, RNAi screens and protein interaction screens perfectly complement each other because the former provides biological context through phenotypes, while the latter provides mechanistic explanations for these phenotypes (at least in ideal cases).

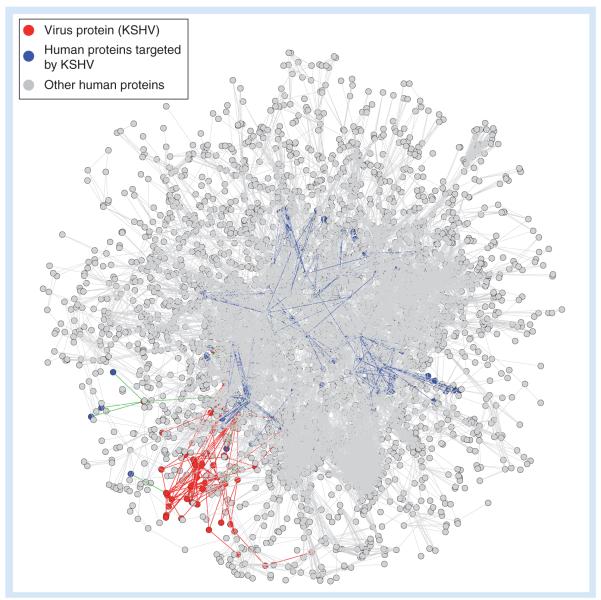

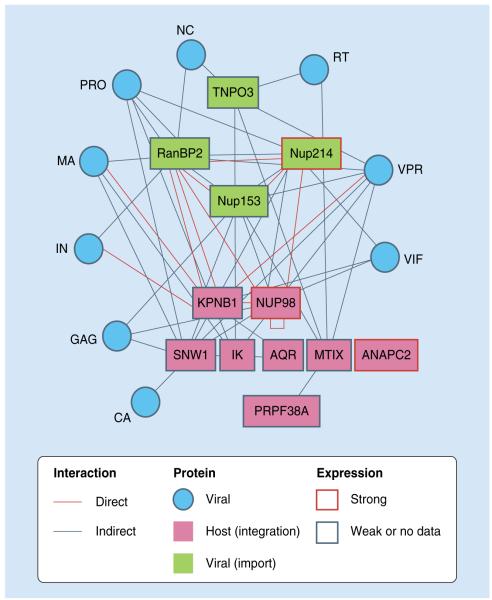

The experiments by Brass and Konig et al. identified 284 and 295 required cell factors, respectively, with an overlap of 13 genes. Similar to two-hybrid screens, experimental conditions appear to dramatically affect the results of these screens. A combination of RNAi data and protein interaction data yielded a host–pathogen interaction network containing 213 functionally validated and 169 predicted HIV host cellular nodes, which were connected via 2291 binary protein interactions, and 318 interactions to HIV-encoded proteins. This analysis showed how tightly integrated virus and host proteins interact in a functional as well as in a pathological context (Figures 2 & 3).

Figure 2. Global view of host–virus interactions.

KSHV proteins (red) interact with specific targets in a human network consisting of 10,636 interactions among 3169 human proteins (gray). Human proteins interacting with KSHV proteins are shown as blue nodes. Interactions between viral proteins are depicted as red edges, those between viral and cellular proteins as green edges, and those between cellular level 1 and 2 proteins as blue edges.

KSHV: Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus.

Adapted from [18].

Figure 3. Host factors important for nuclear import of HIV-1 PICs and viral DNA integration.

Biochemical relationships between proteins involved in integration (pink) and nuclear import (green) and direct or indirect interactions among those proteins and with proteins encoded by HIV (blue).

Adapted from [27].

CA: Capsid; IN: Integrase; MA: Matrix; NC: Nucleocapsid; PIC: Preintegration complex; PRO: Protease; RT: Reverse transcriptase.

Databases & available data

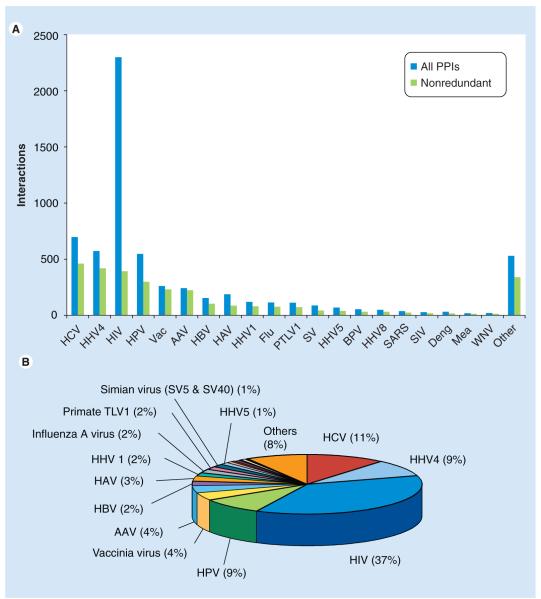

Recent success in generating high-throughput data for protein interactions has caused the creation of several online repositories. The creation of these databases fulfills the need for having a well organized repository of interactions and proper curation of the data. Some databases have specialized in pathogen–host protein interactions (Table 5). The taxonomic composition and the protein interaction data of one of these databases is summarized in Table 3 and Figure 4.

Table 5.

Databases collecting host–virus protein–protein interactions.

Figure 4. Protein–protein interactions of viruses.

A few viruses are heavily overrepresented in databases such as VirusHostNet [36], the source of data of this diagram.

AAV: Adeno-associated virus; BPV: Bovine papilloma virus; Deng: Dengue virus; Flu: Influenza; HAV: Human adeno virus; HHV: Human herpes virus; HPV: Human papilloma virus; Mea: Measles; PTLV1: Primate T lymphotropic virus; SARS: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SIV: Simian immunodeficiency virus; SV: Simiar virus; Vac: Vaccinia; WNV: West Nile virus.

Most remarkable is the fact that only a handful of viruses has been studied intensively enough to reveal a significant number of interactions. Most importantly, HIV (2760 protein–protein interactions [PPIs] according to VirusHostNet), hepatitis (899), as well as approximately five other viruses for which more than 100 interactions are available. Given the number of interactions per protein in HIV, systematic screens of larger viruses, such as human herpesviruses, which encode on the order of 100 proteins, will undoubtedly reveal many thousands of additional interactions, even though only a fraction of them may be biologically relevant.

Computational prediction of host–virus interactions

A few attempts have been made to predict the interactions of viruses and their hosts, usually by predicting homologous interactions (‘interologs’) in related species [18,23]. However, some authors have suggested going beyond such approaches by taking other criteria into account. Dyer et al. [28] combined a strategy invented by Sprinzak and Margalit [29] that infers interactions among domains based on their occurrence in Y2H data. Dyer et al. combined this domain-based approach with Bayesian statistics to predict interactions among humans and Plasmodium falciparum, the malaria parasite. Even though the study validated their predictions by topological features such as the proximity of targeted proteins in a network and by coexpression (from microarray data), they did not attempt to verify these interactions experimentally.

Computational analysis & systems biology of virus-host interactions

Dyer et al. published one of the first systematic analyses of host–pathogen interactions with a focus on virus–human interactions [20]. First, they collected experimentally verified data of pathogen–human protein interactions from seven different databases. Data from 190 different strains were grouped into 54 taxonomically related clusters, including 35 groups of viruses. Interestingly, of the 10,477 human–pathogen interactions identified, 98.3% where derived from viral systems and 77.9% of this corresponded to the human–HIV system (Table 3). 182 unique human proteins with more than one viral interacting partner were identified. Dyer et al. found that both viral and bacterial pathogens tend to interact with human hubs (i.e., proteins with many interacting [human] partners). In addition, pathogens also interact preferentially with bottlenecks; that is, proteins that are connecting many other proteins throughout the network.

In general, virus–host networks can be analyzed by the same tools that have been used for single-species networks [30]. Tools such as Cytoscape [31] and its plugins allow users to highlight functional or taxonomic groups such as viruses and their hosts (Figures 2 & 3). Such graph analyses have shown, among other things, that the attack tolerance of viral networks is surprisingly larger than that of cellular organisms [18].

Do viruses attack specific pathways or functions?

Viruses typically affect specific hosts and, within them, specific tissues and cells. This can be easily explained by their binding specificity to certain receptor proteins. However, do they also attack specific pathways within these cells, based on the interactions with host proteins? Several studies support this hypothesis.

In their global analysis of host–pathogen interactions Dyer et al. found an over-representation of gene ontology terms among the target proproteins of 21 different pathogens. They identified 91 so-called biclusters; that is, pairs of interacting protein groups from host and pathogen. Each of these biclusters contained between two and 40 enriched gene ontology terms among their human targets. This clearly shows that most, if not all, pathogens target very specific pathways within their host cells.

A similar analysis was part of de Chassey’s analysis of HCV–human interactions [22]. HCV preferentially attacks three different networks, namely the insulin, Jak/STAT and TGF-β networks. These findings confirm previous observations that chronic infection by HCV is associated with insulin resistance. Similarly, TGF-β plays an important role in the maintaining cell growth and differentiation of the liver, the main target of HCV. Accordingly, the TGF-β response appears to be impaired in HCV infection.

Can large-scale systems biology help clinical medicine?

Large-scale screens for host–pathogen protein–protein interactions only began a few years ago and are still in a phase of collecting low-hanging fruit. As shown above, it will take a while to saturate these screens and obtain comprehensive lists of interactions. It will then take years to evaluate these datasets and identify the biologically relevant interactions, although recent functional screens, such as RNAi screens, will accelerate such validation. While RNAi screens can identify functional interactions they usually do not provide immediate molecular explanations of their phenotypes. Protein interaction screens can provide such explanations.

Many hope that a complete understanding of all molecular interactions in a cell and between cells (including pathogens) will eventually suggest rational approaches to design drugs and other treatments. Indeed, certain interactions have been harnessed to design antiviral drugs, such as the anti-HIV drug Maraviroc [32] or anti-HCV peptides (e.g., [33]).

Developing drugs takes time. However, a combination of large-scale interaction screening, structural genomics, systems biology and computational biology, as well as small-scale analysis will identify critical interactions and help to design small molecules that inhibit them. Together with the analysis of proteins binding to such drug candidates it will also be possible to identify other proteins that bind to these drugs and thus make them more specific to avoid side effects [34]. That said, we are in the lucky position to be at the beginning of a new era of medicine, whose research paths are wide open but nevertheless clear enough to see their future benefits, even if it may take decades to turn them into real treatments for patients.

Conclusion

Despite a number of encouraging large-scale screens (HCV, herpesviruses) small-scale data still dominate host–virus research (especially in HIV). Current data is not only insufficient to draw global conclusions, it is also insufficient to construct reliable predictive models of host–virus biology. More data from a more diverse set of screens and techniques is required to achieve a complete coverage of all host–virus interactions.

Future perspective

Given the ever-increasing throughput of protein interaction screens, using both Y2H as well as protein complex purification and mass spectrometry, a flood of new interaction data is expected over the next 5–10 years. This will be supplemented by data from methods which are not ready for large-scale screens yet, such as luminescence-based mammalian interactome mapping assays [35] or alternative two-hybrid systems [11].

In combination with data from microarray or next-generation transcript sequencing, RNAi screens and other large-scale screens, this will eventually provide sufficient data to be integrated into truly systems biology-level models. Advances in computational biology, modeling and visualization will allow us to simulate the events during infection in silico, so that both researchers and the general public will gain a better understanding of infection processes.

Detailed interaction maps will also allow us to understand and predict the tissue and cell specificity of viral infections. Equally important, human genome sequencing of many thousand individuals will provide enough data to correlate human variation with their susceptibility to viral infection. In combination with data from structural genomics, molecular docking will eventually predict, on the single amino acid level, which human variants will bind to which virus and in what way. In the 10-year outlook this will give way to new drugs designed specifically for particular virus–human interactions and their targeted treatment.

Executive summary.

Experimental methods to study host–pathogen interactions

- Virion purifications and mass spectrometry (MS) screens:

- – Purified virion particles contain host proteins and thus suggest interactions between virus and associated host proteins

- – Dozens of studies identifying virion and host proteins have been published

- – Protein separation/purification and MS-based proteomics detect proteins in complexes and thus (usually) indirect interactions.

- Protein interaction screens using the yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) system:

- – The majority of virus–host interactions has been found in small-scale studies with HIV leading by far with at least 2600 interactions

- – Y2H screens detect direct binary interactions but have a large false-negative rate

- – Y2H screens are independent of physiological protein levels.

- Intraviral interactomes:

- – Several viral proteomes have been systematically screened for intraviral interactions (several phage, herpesviruses, vaccinia and HCV).

- Systematic Y2H virus–host interaction screens:

- – Despite many screens for individual viral proteins this has been done for only a few viruses on a systematic and larger scale: HCV, herpesviruses and some Streptococcus phage.

- Protein interaction screens & functional screens: RNAi

- – RNAi and protein interaction screens can be combined to validate and complement each other.

Databases & available data

Several specialized databases specifically collect host–virus interactions.

Computational prediction of host–virus interactions

Virus–host interactions can be predicted, primarily based on homology, although none of these predictions is very reliable.

Computational analysis and systems biology of virus–host interactions

Bioinformatics analysis of host–virus networks use established methods for protein network analysis. They have not been sufficient to model host–virus interactions reliably.

Do viruses attack specific pathways or functions?

Yes. For example, HCV appears to target specifically the insulin, Jak/STAT and TGFβ networks.

Can large-scale systems biology help clinical medicine?

Not yet, but with the advent of more interaction data, detailed interaction site mapping, structural genomics and databases of human variation, we expect prediction of individual susceptibility and personalized treatments within approximately 10 years.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank SV Rajagopala, Roman Häuser and Jürgen Haas for their permission to quote unpublished data.

Financial & competing interests disclosure This work was supported by the J Craig Venter Institute, the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg, and NIH grant RO1GM79710.

Footnotes

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jorge Mendez-Rios, J Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), 9704 Medical Center Drive, Rockville, MD 20850, USA Tel.: +1 301 496 4617 jdmendez@infomedicint.com.

Peter Uetz, J Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), 9704 Medical Center Drive, Rockville, MD 20850, USA Tel.: +1 301 795 7589 Fax: +1 301 294 3142 uetz@jcvi.org and Institut fu̇r Toxikologie und Genetik, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, 76021 Karlsruhe, Germany.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Fiers W, Contreras R, Duerinck F, et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of the replicase gene. Nature. 1976;260(5551):500–507. doi: 10.1038/260500a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimmock NJ, Easton AJ, Leppard K. Introduction to Modern Virology. 6th Edition Blackwell Publishing, Oxford; UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wommack KE, Colwell RR. Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000;64(1):69–114. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.69-114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prescott L. Microbiology. Wm C Brown Publishers; IA, USA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailer SM, Haas J. Connecting viral with cellular interactomes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2009;12(4):453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tobe T, Beatson SA, Taniguchi H, et al. An extensive repertoire of type III secretion effectors in Escherichia coli O157 and the role of lambdoid phages in their dissemination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(40):14941–14946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604891103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Piersanti S, Martina Y, Cherubini G, Avitabile D, Saggio I. Use of DNA microarrays to monitor host response to virus and virus-derived gene therapy vectors. Am. J. Pharmacogenom. 2004;4:345–356. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200404060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forst CV. Host–pathogen systems biology. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11(5–6):220–227. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maxwell KL, Frappier L. Viral proteomics. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2007;71(2):398–411. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00042-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chertova E, Chertov O, Coren LV, et al. Proteomic and biochemical analysis of purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 produced from infected monocyte-derived macrophages. J. Virol. 2006;80(18):9039–9052. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01013-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golemis EE. Protein–Protein Interactions – a Molecular Cloning Manual. 2nd Edition Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aloy P, Russell RB. The third dimension for protein interactions and complexes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002;27(12):633–638. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitre S, Alamgir M, Green JR, Dumontier M, Dehne F, Golshani A. Computational methods for predicting protein–protein interactions. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2008;110:247–267. doi: 10.1007/10_2007_089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajagopala SV, Titz B, Goll J, et al. The protein network of bacterial motility. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2007;3:128. doi: 10.1038/msb4100166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun P, Tasan M, Dreze M, et al. An experimentally derived confidence score for binary protein–protein interactions. Nat. Methods. 2009;6(1):91–97. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, Braun P, Yildirim MA, et al. High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science. 2008;322(5898):104–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1158684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uetz P, Rajagopala SV, Dong YA, Haas J. From ORFeomes to protein interaction maps in viruses. Genome Res. 2004;14(10B):2029–2033. doi: 10.1101/gr.2583304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uetz P, Dong YA, Zeretzke C, et al. Herpesviral protein networks and their interaction with the human proteome. Science. 2006;311(5758):239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1116804.▪ One of the first attempts to integrate experimental and theoretical data into a model of host–virus interactions.

- 19.Fu W, Sanders-Beer BE, Katz KS, Maglott DR, Pruitt KD, Ptak RG. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1, human protein interaction database at NCBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D417–D422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyer MD, Murali TM, Sobral BW. The landscape of human proteins interacting with viruses and other pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(2):E32. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040032.▪ Probably the first attempt to analyze global patterns of host–virus interactions.

- 21.Flajolet M, Rotondo G, Daviet L, et al. A genomic approach of the hepatitis C virus generates a protein interaction map. Gene. 2000;242(1–2):369–379. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00511-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Chassey B, Navratil V, Tafforeau L, et al. hepatitis C virus infection protein network. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2008;4:230. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.66.▪ One of the first comprehensive studies of host–virus interactions.

- 23.Calderwood MA, Venkatesan K, Xing L, et al. Epstein–Barr virus and virus human protein interaction maps. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(18):7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702332104.▪ First sytematic screen of both intraviral and host–virus interaction networks of a human virus.

- 24.Fossum E, Baiker A, Friedel CC, et al. Evolution and divergence of herpesviral protein interaction networks. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(9):e1000570. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000570.▪ Systematic analysis of intraviral interactions among five human herpesviruses.

- 25.Rajagopala SV, Hughes KT, Uetz P. Benchmarking yeast two-hybrid systems using the interactions of bacterial motility proteins. Proteomics. 2009;9(23):5296–5302. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brass AL, Dykxhoorn DM, Benita Y, et al. Identification of host proteins required for HIV infection through a functional genomic screen. Science. 2008;319(5865):921–926. doi: 10.1126/science.1152725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.König R, Zhou Y, Elleder D, et al. Global analysis of host–pathogen interactions that regulate early-stage HIV-1 replication. Cell. 2008;135(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyer MD, Murali TM, Sobral BW. Computational prediction of host–pathogen protein–protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(13):I159–I166. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sprinzak E, Margalit H. Correlated sequence-signatures as markers of protein–protein interaction. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;311:681–692. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goll J, Uetz P. Analyzing protein interaction networks. In: Lengauer T, editor. Bioinformatics – From Genomes to Therapies. Wiley-VCH; Germany: 2007. pp. 1121–1177. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorr P, Westby M, Dobbs S, et al. Maraviroc (UK-427,857), a potent, orally bioavailable, and selective small-molecule inhibitor of chemokine receptor CCR5 with broad-spectrum anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49(11):4721–4732. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.11.4721-4732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lamarre D, Anderson PC, Bailey M, et al. An NS3 protease inhibitor with antiviral effects in humans infected with hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2003;426(6963):186–189. doi: 10.1038/nature02099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hantschel O, Rix U, Superti-Furga G. Target spectrum of the BCR–Abl inhibitors imatinib, nilotinib and dasatinib. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2008;49(4):615–619. doi: 10.1080/10428190801896103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barrios-Rodiles M, Brown KR, Ozdamar B, et al. High-throughput mapping of a dynamic signaling network in mammalian cells. Science. 2005;307(5715):1621–1625. doi: 10.1126/science.1105776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navratil V, De Chassey B, Meyniel L, et al. VirHostNet: a knowledge base for the management and the analysis of proteome-wide virus–host interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D661–D668. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saphire AC, Gallay PA, Bark SJ. Proteomic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus using liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry effectively distinguishes specific incorporated host proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2006;5(3):530–538. doi: 10.1021/pr050276b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baldick CJ, Jr, Shenk T. Proteins associated with purified human cytomegalovirus particles. J. Virol. 1996;70(9):6097–6105. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6097-6105.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Varnum SM, Streblow DN, Monroe ME, et al. Identification of proteins in human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) particles: the hCMV proteome. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):10960–10966. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.10960-10966.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kattenhorn LM, Mills R, Wagner M, et al. Identification of proteins associated with murine cytomegalovirus virions. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):11187–11197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11187-11197.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johannsen E, Luftig M, Chase MR, et al. Proteins of purified Epstein–Barr virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(46):16286–16291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407320101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu FX, Chong JM, Wu L, Yuan Y. Virion proteins of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 2005;79(2):800–811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.800-811.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bechtel JT, Winant RC, Ganem D. Host and viral proteins in the virion of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J. Virol. 2005;79(8):4952–4964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4952-4964.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bortz E, Whitelegge JP, Jia Q, et al. Identification of proteins associated with murine γ-herpesvirus 68 virions. J. Virol. 2003;77(24):13425–13432. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.24.13425-13432.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen ON, Houthaeve T, Shevchenko A, et al. Identification of the major membrane and core proteins of vaccinia virus by two-dimensional electrophoresis. J. Virol. 1996;70(11):7485–7497. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7485-7497.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoder JD, Chen TS, Gagnier CR, Vemulapalli S, Maier CS, Hruby DE. Pox proteomics: mass spectrometry analysis and identification of vaccinia virion proteins. Virol. J. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chung CS, Chen CH, Ho MY, Huang CY, Liao CL, Chang W. Vaccinia virus proteome: Identification of proteins in vaccinia virus intracellular mature virion particles. J. Virol. 2006;80(5):2127–2140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2127-2140.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang C, Zhang X, Lin Q, Xu X, Hu Z, Hew CL. Proteomic analysis of shrimp white spot syndrome viral proteins and characterization of a novel envelope protein vp466. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2002;1(3):223–231. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m100035-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai JM, Wang HC, Leu JH, et al. Genomic and proteomic analysis of thirty-nine structural proteins of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 2004;78(20):11360–11370. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.20.11360-11370.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie X, Xu L, Yang F. Proteomic analysis of the major envelope and nucleocapsid proteins of white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 2006;80(21):10615–10623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01452-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartel PL, Roecklein JA, Sengupta D, Fields S. A protein linkage map of Escherichia coli bacteriophage T7. Nat. Genet. 1996;12(1):72–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCraith S, Holtzman T, Moss B, Fields S. Genome-wide analysis of vaccinia virus protein–protein interactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97(9):4879–4884. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shapira SD, Gat-Viks I, Shum BOV, et al. A physical and regulatory map of host–influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 2009;139:1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.018.▪ Integration of protein–protein interactions, siRNA data and expression patterns in influenza infection.

- 54.Kerrien S, Alam-Faruque Y, Aranda B, et al. Intact – open source resource for molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D561–D565. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Reguly T, Boucher L, Breitkreutz A, Tyers M. Biogrid: a general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D535–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salwinski L, Miller CS, Smith AJ, Pettit FK, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. The database of interacting proteins: 2004 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D449–D451. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chatr-Aryamontri A, Ceol A, Peluso D, et al. Virusmint: a viral protein interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D669–D673. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) files and discussions http://talk.ictvonline.org/media/p/272.aspx.

- 102.NCBI, viral genomes statistics. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/GenomesHome.cgi?taxid=10239&hopt=stat.

- 103.Health Sciences Library Services, University of Pittsburgh, PA, USA protein–protein interactions. www.hsls.pitt.edu/guides/genetics/obrc/enzymes_pathways/protein_protein_interactions.

- 104.BioGPS: the gene portal hub http://symatlas.gnf.org.

- 105.IntAct www.ebi.ac.uk/intact.

- 106.BioGRID www.thebiogrid.org.

- 107.DIP: database of interacting proteins. http://dip.doe-mbi.ucla.edu/dip.

- 108.MINT: Molecular INTeraction database. http://mint.bio.uniroma2.it/mint.

- 109.VirHostNet. http://pbildb1.univ-lyon1.fr/virhostnet/release.php.

- 110.HIV-1, human protein interaction database. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/RefSeq/HIVInteractions.