Abstract

Post-weaning social isolation of rodents is used to model developmental stressors linked to neuropsychiatric disorders including schizophrenia as well as anxiety and mood disorders. Isolation rearing produces alterations in emotional memory and hippocampal neuropathology. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) signaling has recently been shown to be involved in behavioral effects of isolation rearing. Activation of the CRF2 receptor is linked to stress-induced alterations in fear learning and may also be involved in long term adaptation to stress. Here we tested the hypothesis that CRF2 contributes to isolation rearing effects on emotional memory. At weaning, mice were housed either in groups of 3 or individually in standard mouse cages. In adulthood, isolation-reared mice exhibited significant reductions in context-specific, but not cue-specific, freezing. Isolation reared mice exhibited no significant changes in locomotor exploration during brief exposure to a novel environment, suggesting that the reduced freezing in response to context cues was not due to activity confounds. Isolation rearing also disrupted context fear memory in mice with a CRF2 gene null mutation, indicating that the CRF2 receptor is not required for isolation effects on fear memory. Thus, isolation rearing disrupts hippocampal-dependent fear learning as indicated by consistent reductions in context-conditioned freezing in two separate cohorts of mice, and these effects are via a CRF2-independent mechanism. These findings may be clinically relevant because they suggest that isolation rearing in mice may be a useful model of developmental perturbations linked to disruptions in emotional memory in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Keywords: social isolation, fear conditioning, corticotropin releasing factor, emotional memory, locomotor activity, mice

Introduction

Social isolation rearing of rodents is a developmental manipulation in which rodents are singly housed upon weaning. Isolation rearing produces neuroanatomical and behavioral changes in rodents and has been used to model several neuropsychiatric disorders ranging from schizophrenia to anxiety and depression [10,21]. Hippocampal abnormalities (e.g. decreased hippocampal volume) have been observed in several anxiety and mood disorders including PTSD and depression [4,5]. These alterations correspond with disruptions in hippocampal-dependent memory tasks [5,12]. Consistent with these observations, social isolation rearing of rodents interferes with the development of the limbic system which is involved in regulation of emotional behaviors and learning and memory formation (reviewed in [10]). Both rats [37] and mice [35] reared in isolation exhibit reduced contextual fear learning, suggesting isolation rearing may disrupt hippocampal learning and memory.

The mechanism by which isolation rearing alters contextual fear memory is unknown. The CRF system, a family of peptides mediating the neuroendocrine and behavioral response to stress [14], plays a critical role in postnatal neurodevelopment in forebrain including hippocampus [6]. Clinically, the CRF system appears to be affected by early childhood experiences, suggesting that stressors during development modulate long term CRF signaling [3]. Recent evidence suggests that isolation rearing in rats disrupts CRF receptor 1 and 2 signaling in the amygdala [8] and the dorsal raphe [19]. Indeed, changes in CRF2 receptor signaling mediate isolation rearing effects on anxiety-like behavior as measured by social interaction [19]. CRF2 receptors are highly expressed in the hippocampus in rats and mice [32] and thus may also mediate the contextual fear learning deficits observed with isolation rearing. In mice, acute stress modulates contextual fear conditioning via a CRF2 receptor specific mechanism, with the direction of CRF2 activation effects dependent upon the region of activation (e.g. septum vs. hippocampus) and the duration of time between the acute stressor and fear conditioning (e.g. 0 hours vs. 3 hours) [25,27,30]. To test the overall hypothesis that isolation rearing decreases contextual fear learning via a CRF2 receptor mechanism, we examined fear learning in CRF2 receptor knockout mice raised in either isolation or group housing. The use of these genetically altered mice allows for the examination of mechanisms responsible for the effects of long-term environmental manipulation during development (e.g. isolation rearing) [24].

In the present study, we first sought to replicate the findings of reduced fear conditioning in C57BL/6 mice [35]. To control for possible locomotor activity changes or unconditioned anxiety effects of isolation on freezing measures, we also examined the effects of isolation rearing on locomotor exploration in a novel environment under low- and mild-stress conditions (i.e. in darkness or under bright light). Next, we examined the effect of isolation rearing on fear conditioning in CRF2 wildtype (WT) and knockout (KO) mice.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Male wild-type C57BL/6J mice derived from 22 litters at the University of California, San Diego were used. Each litter was represented in both social and isolate rearing conditions. On postnatal day 28, pups were weaned and housed in standard mouse cages in groups of either three per cage (social condition) or one per cage (isolate condition) for the duration of the study. All mice were housed in a temperature and humidity-controlled room with a 12:12 h reverse light/dark cycle (lights off at 08:00) and food and water available ad libitum. Behavioral testing began at 8 weeks post-weaning (i.e., 3 months of age). First, a brief assessment of locomotor activity in a novel environment under different lighting conditions was conducted (n = 5–7/housing/lighting condition). The locomotor test was followed by context and cued fear conditioning testing (n = 10/group). An additional male cohort of heterozygously bred CRF2 receptor wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice (backcrossed >N14 to C57BL/6J mice; [7]) were weaned under the same social or isolation conditions described above and subsequently tested for locomotor activity and fear conditioning (n = 7–10/group). All behavioral testing occurred between 10:00 and 18:00 and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as approved by the University of California, San Diego.

Locomotor activity under low and mild stress conditions

Locomotor activity and investigatory behavior were measured in 10 mouse behavioral pattern monitors (BPM; San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) [26]. The design of the mouse BPM system is based on the rat BPM (for a detailed description, see [11]). The mouse BPM chamber is a clear Plexiglas box containing a 30 × 60 cm holeboard floor. Each chamber is enclosed in a ventilated outer box to protect it from light and ambient noise from outside the chambers. The chamber contains eleven 1.4-cm holes (three in the floor and eight in the walls), each provided with an infrared photobeam to detect investigatory nosepokes (holepokes). The location of the mouse is obtained from a grid of 12 × 24 photobeams 1 cm above the floor. Rearing is detected by an array of 16 photobeams placed 2.5 cm above the floor and aligned with the long axis of the chamber. The status of the photobeams is sampled every 55 msec. A change in the status of photobeams triggers the storage of the information in a binary data file together with the duration of the photobeam status. Subsequently, the raw data files are transformed into (x,y,t event) ASCII data files comprised of the (x,y) location of the animal in the mouse BPM chamber with a resolution of 1.25 cm, the duration of each event (t), and whether a holepoke or rearing occurred (event).

In the first experiment, isolation and socially-reared C57 mice were assigned to testing either in a dark or lit chamber. In the subsequent experiment, WT and KO CRF2 mice reared in social isolation or in groups were tested in a lit chamber. The animals were brought into the testing room under a black cloth 60 min before testing. During testing, a white noise generator produced background noise at 65 dB. Data were collected for 10 min. The chambers were cleaned thoroughly with water between testing sessions. Distance traveled (cm), center duration (min), center entries, rears, and hole pokes were analyzed using an ANOVA with two between subjects factors (Rearing condition; Lighting in the first experiment; Rearing condition; Genotype in the second experiment).

Fear Conditioning

The procedure used in the fear conditioning experiment was adapted from previous studies [31]. Specifically, fear conditioning occurred in four transparent acrylic chambers (25 cm wide × 18 cm high × 21 cm deep, San Diego Instruments) each situated inside a sound attenuating box. A house light (15-W bulb) illuminated the chamber during all sessions. A small fan, located on an adjacent wall of the sound-attenuating box, was also turned on during all sessions. A shock floor consisting of 32 stainless steel rods was wired to a shock generator (San Diego Instruments) for foot shock delivery. Presentation of unconditioned (scrambled foot shock) and conditioned (auditory tone, 4 kHz Sonalert pure tone generator) stimuli was controlled by computer. Sixteen infrared photobeams surrounding the chamber were used to continuously detect the mouse’s movements, and the computer recorded the number of beam interruptions and latencies to beam interruptions during all sessions. The chambers were cleaned with water after each session.

On the day of conditioning, mice were transported in their home cages to a room located adjacent to the testing room. After a 60 min habituation period to the room, mice were placed in the conditioning chamber. After an acclimation period (2 min), mice were presented with a tone (20 sec, 75 dB, 4 kHz) that coterminated with a foot shock (1 sec, 0.5 mA). A total of three tone-shock pairings were presented with an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 40 seconds. Post-shock freezing was measured for 20 sec following the final shock presentation. Mice were removed from the chamber and returned to their home cage 40 sec after the last shock. Twenty-four hours later, subjects were returned to the conditioning chamber for a context fear retention test. The features of the chamber were identical to those used during conditioning. The context test lasted 8 min during which time no shocks or tones were presented. Freezing was scored for the duration of the session as detailed below. Twenty-four hours after the context test, mice were tested for retention of auditory fear (cued retention test). The chambers were altered on several dimensions (tactile, odor, visual) for the tone test in order to minimize generalization from the conditioning context. Specifically, the grid floors were replaced with smooth plastic floors cleaned with peppermint scent between each run. The walls of the chamber were adorned with various geometric shapes made from green construction paper. After a 2 min acclimation period, during which time no tones were presented, a single tone was presented continuously for 6 min. Freezing was scored during the tone presentation. Baseline freezing during the acclimation period prior to the tone presentation was also measured to assay for generalization of fear. Subjects were returned to their home cage immediately after termination of the tone.

The conditioned fear response, freezing, was defined as the absence of any movement except that required for respiration and was hand scored during the context and cued tests using a time-sampling procedure. Every 10 sec, the mouse was observed for 1 sec and scored as either freezing or active. This determination was made the instant the sample was taken. Freezing was converted into a percentage by dividing the number of freezing instances observed by the total number of observations and then multiplying by 100. Freezing during the context test was also determined using an automated method that relied upon the latency to break infrared beams to calculate freezing. The 8 min context test was divided into 5 sec epochs and the latency to break the first of three photobeams within each 5 sec interval was recorded. If a mouse took longer than 1 sec to break the first beam, then an instance of freezing was scored. The number of 5 sec intervals during which an instance of freezing was observed was divided by the total number of 5 sec intervals and multiplied by 100 to determine the % freezing. A correlation for percent freezing obtained using hand scoring vs. automated methods was calculated based on the data collected during the context test and was determined to be Pearson’s r = 0.90, p < 0.0001. Assessment of post-shock freezing following the final shock presentation during conditioning was also obtained using the automated method.

Freezing during the post-shock period in the conditioning session was analyzed using a between subjects (Rearing condition) ANOVA. During the context retention test, freezing was averaged over the 8-min session and analyzed using ANOVA with rearing condition and sex as the between-subjects factors. For the cued retention test, freezing prior to (pre-tone) and during the tone presentation was analyzed separately using a one-way ANOVA (Rearing Condition). In the CRF2 experiment, the factor of Genotype (WT or KO) was also included in the ANOVAs stated above. Post-hoc simple ANOVAs and t-tests were performed on significant results.

Results

Locomotor Activity

The effects of isolation rearing on locomotor activity are reported in Table 1. Overall, distance traveled, rears, time spent in the center of the arena, and number of center entries was greater in the dark arena compared to the lit arena [Lighting: Fs(1,21) > 11.24, ps < 0.003]. There was no effect of rearing condition on distance traveled, center time, center entries, and hole-poking behavior in either the dark or lit conditions. There was a strong non-significant trend for isolated mice to exhibit more rears than socially housed mice [F(1,21)=4.22, p=0.053]. A similar pattern of housing effects was observed in the CRF2 WT and KO cohort, with no effect or interaction with genotype (data not shown).

Table 1.

Effect of rearing condition on open field measures (10 min)

| Lights Off | Lights On* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Field Measure | Social | Isolate | Social | Isolate |

| Distance (cm) | 2849.8 ± 198.7 | 3028.7 ± 126.2 | 1936.5 ± 113.8 | 2212.2 ± 292.3 |

| Center Duration (min) | 0.9 ± 0.08 | 0.8 ± 0.09 | 0.4 ± 0.09 | 0.4 ± 0.09 |

| Center Entries | 48.6 ± 6.8 | 41.3 ± 4.5 | 19.6 ± 3.4 | 18.0 ± 4.5 |

| Rears | 70 ± 7 | 89 ± 10 | 52 ± 3 | 61 ± 6 |

| Hole Pokes | 30 ± 3 | 30 ± 2 | 29 ± 4 | 31 ± 5 |

Note:

p < 0.003 relative to lights off condition for distance, center duration, center entries, and rears

Fear Conditioning

Mean percent freezing after the final tone-shock pairing (post-shock freezing) did not vary with rearing condition (Mean ± SEM; Social: 55.6 ± 10.0; Isolate: 45.0 ± 10.4). During the context test, isolation rearing decreased freezing [Rearing Condition: F(1, 18) = 10.56, p < 0.0045] (Figure 1A). A significant effect of rearing condition was also observed during the context test when data were collected using automated methods [Rearing Condition: F(1, 18) = 6.04, p < 0.03] (Mean ± SEM: Social: 39.7 ± 4.6; Isolate: 23.8 ± 4.6). As stated above, the correlation for hand scoring vs. automated was Pearson’s r = 0.90, p < 0.0001.

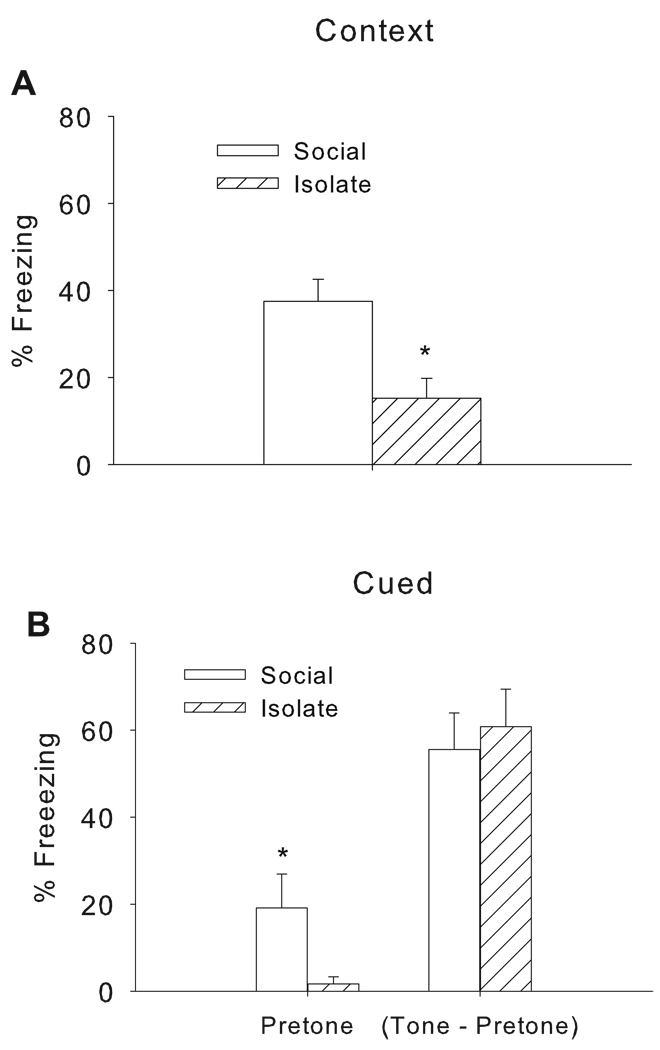

Figure 1.

Isolation rearing disrupts contextual (A) but not cued (B) fear learning. Mice reared in social groups (Social) or under isolation (Isolate) were trained for fear conditioning to a tone CS. Twenty four hours after training mice were re-exposed to the conditioning context (Panel A). Twenty four hours later mice were placed back into the chambers which had altered visual, tactile and odor cues and tested for freezing during the tone CS (Panel B). Note freezing to the tone CS is reported as total freezing to tone minus freezing before tone was presented. Data are expressed as mean+/−SEM of percent freezing. *p<0.05 vs. Socially housed group (Panel A) or Isolate group (Panel B), Tukey’s post hoc test.

The mean percent freezing prior to and during the tone presentation in the cued retention test is shown in Figure 1B. Pretone freezing was higher in the socially reared group compared to isolates [Rearing Condition: F(1, 18) = 4.86, p < 0.05]. Because of the group differences in baseline freezing during the pretone period, pretone freezing was subtracted from freezing that occurred during the tone period to allow for specific evaluation of conditioned auditory retention. Isolation rearing did not affect cue-specific freezing (F(1,18) = 0.19, p = 0.66 (Figure 1B). The same pattern of results (i.e., no effect of isolation rearing on cued freezing) remains when pretone freezing is not subtracted (F(1,18) = 1.52, p = 0.23).

In order to examine whether the previously observed isolation-induced deficits in fear conditioning were due to dysregulation of the CRF system, social and isolation-reared male CRF2 receptor WT and KO mice underwent fear conditioning. During the context test, isolation rearing decreased freezing in both WT and KO mice [Rearing Condition: F(1, 33) = 13.94, p < 0.0007] with no effect of Genotype and no Genotype × Rearing condition interaction (Figure 2A).

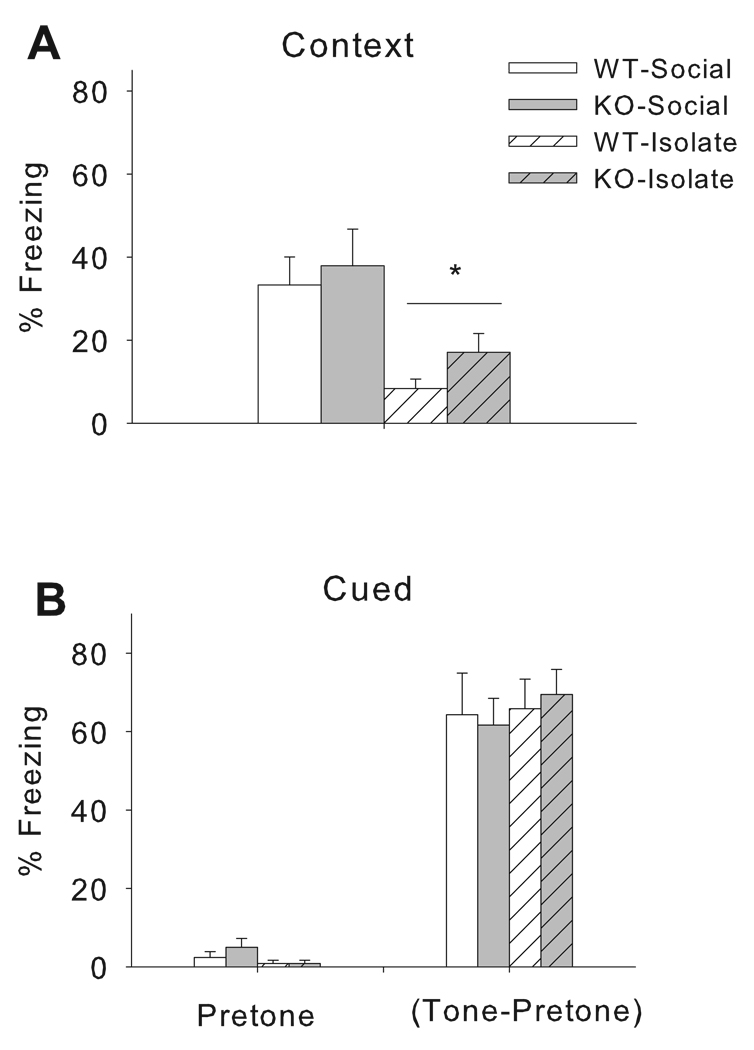

Figure 2.

Isolation induced disruption of context fear learning is independent of CRF2 genotype. CRF2 wildtype (WT) and gene knockout (KO) mice reared in social groups (Social) or under isolation (Isolate) were trained for fear conditioning to a tone CS. Twenty four hours after training mice were re-exposed to the conditioning context, with isolation reared mice exhibiting a significant reduction in freezing across genotype (Panel A). Twenty four hours later mice were placed back into the chambers which had altered visual, tactile and odor cues and tested for freezing during the tone CS (Panel B). Note freezing to the tone CS is reported as total freezing to tone minus freezing before tone was presented. Data are expressed as mean+/−SEM of percent freezing, see results section for detailed statistics. *p<0.05 vs. Socially-housed groups (i.e. significant main effect of Rearing Condition).

CRF2 WT and KO mice reared under social conditions tended to have higher levels of baseline freezing during the pretone period compared to isolates (Figure 2B) [Rearing Condition: F(1, 33) = 3.64, p < 0.07], but there was no effect of Genotype or Genotype × Rearing condition interaction for pretone freezing. In order to evaluate auditory retention specifically, pretone freezing was subtracted from freezing that occurred during the tone period. Neither isolation rearing nor genotype affected freezing to the tone.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that isolation rearing produces robust and selective deficits in contextual fear learning. Isolation and socially housed mice did not differ in the level of post-shock freezing observed at the end of the fear conditioning session. Thus, it is unlikely that isolation-induced decreases in contextual fear were due to group differences in processing of the shock or the extent to which the groups acquired the fear conditioning task. During the pretone period of the cued test, socially housed C57BL/6 mice exhibited higher levels of pretone freezing compared to isolates, however this effect was not replicated in the CRF2 WT or KO mice. Importantly, because rearing condition had no effect on freezing during the tone presentation of the cued test, non specific effects on ability to perform the freezing response (e.g. increased activity) is an unlikely explanation for the decreased freezing observed in the isolate group during the context test.

The selective effect of sustained isolation rearing on context, but not cued, fear is consistent with previous observations in rats [37], but contrasts with reports in C57BL/6 mice [35]. In the Voikar study, isolation reared mice displayed less freezing in all conditions (context, pre-tone and cued) [35]. The isolation rearing effect on cued fear in that study, however, could be due to pretone freezing levels, which were relatively high, suggesting that the context was not well masked during the cued test [35]. It should be noted that an effect of isolation rearing on tone freezing was not observed in our study regardless of whether pretone freezing was subtracted from the levels of cued freezing. Our data suggest that the deficit in fear conditioning associated with isolation rearing are relatively specific to context fear. This specificity also rules out a non-selective freezing deficit due to hyperactivity in isolation reared mice. The locomotor activity findings in the present study confirm previous observations that social and isolation reared C57BL/6J mice exhibit similar locomotor activity levels during a brief (<20 min) exposure to a novel environment [23, 34, 35] (although note that isolation rearing does increase activity in other mouse strains [23, 34, 35] as well as over longer testing periods [23].

Although both contextual and cued fear conditioning are amygdala dependent, the hippocampus is predominantly involved in contextual fear conditioning [9,28]. Hippocampal lesions [17,22] and hippocampal infusions of cholinergic antagonists, GABA agonists, or NMDA antagonists [1,36] severely impair contextual fear conditioning, while leaving auditory fear conditioning intact. Because mice (present study) and rats [37] exposed to sustained social isolation exhibit significant reductions in context, but not cued, freezing, these findings may suggest that hippocampal dependent emotional memory is more sensitive to isolation rearing induced disruption. This hypothesis is supported by recent evidence that rats reared in isolation exhibit reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, long term potentiation (a molecular marker of synaptic plasticity required for learning) and reduced spatial learning in the water maze. Interestingly these effects are reversed by exposure to social housing [18], which may explain why social isolation for a short period followed by group housing does not result in fear learning deficits [20]. In order to determine whether isolation rearing-induced deficits in emotional memory extend to other fear-specific tasks reliant upon the hippocampus, future studies could also examine the effects of isolation rearing on trace fear conditioning.

There is strong evidence for isolation rearing to induce several neurochemical and structural changes in the hippocampus. For example, isolation rearing reduces hippocampal immunoreactivity of synaptophysin (a presynaptic protein indicator of synaptic plasticity) [33], reduces parvalbumin and calbindin immunoreactivity in hippocampal GABAergic neurons in rats [13], and disrupts hippocampal neurogenesis in mice [16]. Isolation rearing also decreases presynaptic serotonergic and noradrenergic function in the hippocampus [10]. Alterations in hippocampal structure, such as decreased dendritic length and spine density of pyramidal cells [29], and microtubule instability [2] have also been reported in isolation-reared rats. Together, these findings suggest that the disruptions in performance on hippocampal-dependent tasks, such as contextual fear conditioning, may be related to the hippocampal changes that accompany isolation rearing. Studies that directly link the aforementioned alterations in the hippocampus with isolation-induced deficits in contextual fear conditioning are needed to verify this conclusion.

In the current experiment, isolation rearing-induced impairments in contextual fear conditioning were observed in both CRF2 WT and KO mice, suggesting that CRF2 is not critical for isolation effects on fear conditioning, unlike its modulation of isolation rearing effects on social behavior [19]. Thus although CRF2 activation plays a role in acute stress effects on context fear learning (see introduction), it does not appear to mediate the effects of chronic isolation stress on this behavior. Previous studies have shown that the CRF2 antagonist Anti-Sauvagine 30 injected into the BLA did not affect contextual freezing [15]. Given that CRF binds to both CRF1 and CRF2 receptors [14] and in light of the current finding that social isolation decreases contextual fear despite the absence of CRF2 receptors, it is plausible that CRF1 activation is sufficient to mediate any contributions of the CRF system to the effects of isolation on contextual fear. Indeed, recent evidence indicates that in rats, pharmacological antagonism of the CRF1 receptor blocks isolation-induced disruptions in neurotransmission in the amygdala [8]. Additionally, microinfusions of the CRF1 antagonist DMP696 disrupted the consolidation of conditioned freezing in rats [15]. Additional studies that selectively target CRF1 (e.g., via the use of CRF1 antagonists or CRF1 KO mice) are needed to determine if these results extend to behavioral disruptions such as those observed in contextual fear in isolated mice.

In conclusion, we found that isolation rearing in C57BL/6J mice produces robust and specific effects on context fear learning, which is via a CRF2 receptor-independent mechanism. The lack of housing differences in freezing during the cued task and in locomotor activity suggest that the reduced contextual freezing observed with isolation rearing is not due to activity confounds. Based on the evidence discussed above for alterations in CRF systems with isolation rearing, futures studies will examine the contribution of CRF1 receptors to isolation effects on emotional memory.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge technical assistance from Mahalah Buell and Matthew Schalles and analysis assistance from Virginia Masten. These studies were supported by MH052885, MH076850, MH074697 and by the Veterans Affairs VISN 22 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Dr. Geyer owns an equity interest in San Diego Instruments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Bast T, Zhang WN, Feldon J. The ventral hippocampus and fear conditioning in rats. Different anterograde amnesias of fear after tetrodotoxin inactivation and infusion of the GABA(A) agonist muscimol. Exp Brain Res. 2001;139(1):39–52. doi: 10.1007/s002210100746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi M, Fone KF, Azmi N, Heidbreder CA, Hagan JJ, Marsden CA. Isolation rearing induces recognition memory deficits accompanied by cytoskeletal alterations in rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24(10):2894–2902. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley RG, Binder EB, Epstein MP, Tang Y, Nair HP, Liu W, Gillespie CF, Berg T, Evces M, Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Heim CM, Nemeroff CB, Schwartz A, Cubells JF, Ressler KJ. Influence of child abuse on adult depression: moderation by the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(2):190–200. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2007.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremner JD, Elzinga B, Schmahl C, Vermetten E. Structural and functional plasticity of the human brain in posttraumatic stress disorder. Prog Brain Res. 2008;167:171–186. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)67012-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell S, Macqueen G. The role of the hippocampus in the pathophysiology of major depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29(6):417–426. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Bender RA, Brunson KL, Pomper JK, Grigoriadis DE, Wurst W, Baram TZ. Modulation of dendritic differentiation by corticotropin-releasing factor in the developing hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(44):15782–15787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403975101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coste SC, Kesterson RA, Heldwein KA, Stevens SL, Heard AD, Hollis JH, Murray SE, Hill JK, Pantely GA, Hohimer AR, Hatton DC, Phillips TJ, Finn DA, Low MJ, Rittenberg MB, Stenzel P, Stenzel-Poore MP. Abnormal adaptations to stress and impaired cardiovascular function in mice lacking corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor-2. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):403–409. doi: 10.1038/74255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Djouma E, Card K, Lodge DJ, Lawrence AJ. The CRF1 receptor antagonist, antalarmin, reverses isolation-induced up-regulation of dopamine D2 receptors in the amygdala and nucleus accumbens of fawn-hooded rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(12):3319–3327. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanselow MS, LeDoux JE. Why we think plasticity underlying Pavlovian fear conditioning occurs in the basolateral amygdala. Neuron. 1999;23(2):229–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fone KC, Porkess MV. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of post-weaning social isolation in rodents-relevance to developmental neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(6):1087–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geyer MA, Russo PV, Masten VL. Multivariate assessment of locomotor behavior: pharmacological and behavioral analyses. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;25(1):277–288. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbertson MW, Williston SK, Paulus LA, Lasko NB, Gurvits TV, Shenton ME, Pitman RK, Orr SP. Configural cue performance in identical twins discordant for posttraumatic stress disorder: theoretical implications for the role of hippocampal function. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harte MK, Powell SB, Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA, Reynolds GP. Deficits in parvalbumin and calbindin immunoreactive cells in the hippocampus of isolation reared rats. J Neural Transm. 2007;114(7):893–898. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0627-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauger RL, Risbrough V, Brauns O, Dautzenberg FM. Corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) receptor signaling in the central nervous system: new molecular targets. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5(4):453–479. doi: 10.2174/187152706777950684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hubbard DT, Nakashima BR, Lee I, Takahashi LK. Activation of basolateral amygdale corticotropin-releasing factor 1 receptors modulates the consolidation of contextual fear. Neuroscience. 2007;150(4):818–828. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ibi D, Takuma K, Koike H, Mizoguchi H, Tsuritani K, Kuwahara Y, Kamei H, Nagai T, Yoneda Y, Nabeshima T, Yamada K. Social isolation rearing-induced impairment of the hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with deficits in spatial memory and emotion-related behaviors in juvenile mice. J Neurochem. 2008;105(3):921–932. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JJ, Fanselow MS. Modality-specific retrograde amnesia of fear. Science. 1992;256(5057):675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1585183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu L, Bao G, Chen H, Xia P, Fan X, Zhang J, Pei Pei, Ma L. Modification of hippocampal neurogenesis and neuroplasticity by social environments. Exp Neurol. 2003;183(2):600–609. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lukkes J, Vuong S, Scholl J, Oliver H, Forster G. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor antagonism within the dorsal raphe nucleus reduces social anxiety-like behavior after early-life social isolation. J Neurosci. 2009;29(32):9955–9960. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukkes JL, Mokin MV, Scholl JL, Forster GL. Adult rats exposed to early-life social isolation exhibit increased anxiety and conditioned fear behavior, and altered hormonal stress responses. Horm Behav. 2009;55(1):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukkes JL, Watt MJ, Lowry CA, Forster GL. Consequences of post-weaning social isolation on anxiety behavior and related neural circuits in rodents. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:18. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.018.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips RG, LeDoux JE. Differential contribution of amygdala and hippocampus to cued and contextual fear conditioning. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106(2):274–285. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietropaolo S, Singer P, Feldon J, Yee BK. The postweaning social isolation in C57BL/6 mice: preferential vulnerability in the male sex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197(4):613–628. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell SB, Zhou X, Geyer MA. Prepulse inhibition and genetic mouse models of schizophrenia. Behav Brain Res. 2009;204(2):282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radulovic J, Ruhmann A, Liepold T, Spiess J. Modulation of learning and anxiety by corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) and stress: differential roles of CRF receptors 1 and 2. J Neurosci. 1999;19(12):5016–5025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05016.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Risbrough VB, Masten VL, Caldwell S, Paulus MP, Low MJ, Geyer MA. Differential contributions of dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptors to MDMA-induced effects on locomotor behavior patterns in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(11):2349–2358. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sananbenesi F, Fischer A, Schrick C, Spiess J, Radulovic J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in the hippocampus and its modulation by corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2: a possible link between stress and fear memory. J Neurosci. 2003;23(36):11436–11443. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11436.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders MJ, Wiltgen BJ, Fanselow MS. The place of the hippocampus in fear conditioning. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1–3):217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva-Gomez AB, Rojas D, Juarez I, Flores G. Decreased dendritic spine density on prefrontal cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons in postweaning social isolation rats. Brain Res. 2003;983(1–2):128–136. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Todorovic C, Radulovic J, Jahn O, Radulovic M, Sherrin T, Hippel C, Spiess J. Differential activation of CRF receptor subtypes removes stress-induced memory deficit and anxiety. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(11):3385–3397. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valentinuzzi VS, Kolker DE, Vitaterna MH, Shimomura K, Whiteley A, Low-Zeddies S, Turek FW, Ferrari EA, Paylor R, Takahashi JS. Automated measurement of mouse freezing behavior and its use for quantitative trait locus analysis of contextual fear conditioning in (BALB/cJ x C57BL/6J)F2 mice. Learn Mem. 1998;5(4–5):391–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Pett K, Viau V, Bittencourt JC, Chan RK, Li HY, Arias C, Prins GS, Perrin M, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. Distribution of mRNAs encoding CRF receptors in brain and pituitary of rat and mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428(2):191–212. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001211)428:2<191::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varty GB, Marsden CA, Higgins GA. Reduced synaptophysin immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus of prepulse inhibition-impaired isolation-reared rats. Brain Res. 1999;824(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varty GB, Powell SB, Lehmann-Masten V, Buell MR, Geyer MA. Isolation rearing of mice induces deficits in prepulse inhibition of the startle response. Behav Brain Res. 2006;169(1):162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voikar V, Polus A, Vasar E, Rauvala H. Long-term individual housing in C57BL/6J and DBA/2 mice: assessment of behavioral consequences. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4(4):240–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallenstein GV, Vago DR. Intrahippocampal scopolamine impairs both acquisition and consolidation of contextual fear conditioning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2001;75(3):245–252. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2001.4005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss IC, Pryce CR, Jongen-Relo AL, Nanz-Bahr NI, Feldon J. Effect of social isolation on stress-related behavioural and neuroendocrine state in the rat. Behav Brain Res. 2004;152(2):279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]