Abstract

The combination of diabetes and renal failure is associated with accelerated cardiomyopathy, but the molecular mechanisms of how renal failure drives diabetic heart disease remain elusive. We speculated that the metabolic abnormalities of renal failure will affect the epigenetic control of cardiac gene transcription and sought to determine the histone H3 modification pattern in hearts of type 2 diabetic mice with several degrees of renal dysfunction. We studied the histone H3 modifications and gene expression in the heart of 6-month-old nondiabetic mice and type 2 diabetic db/db mice that underwent either sham surgery or uninephrectomy at 6 weeks of age, which accelerates glomerulosclerosis in db/db mice via glomerular hyperfiltration. Western blotting of hearts from uninephrectomized db/db mice with glomerulosclerosis, albuminuria, and reduced glomerular filtration rate revealed increased acetylation (K23 and 9), phosphorylation (Ser 10), dimethylation (K4), and reduced dimethylation of (K9) of cardiac histone H3 as compared with db/db mice with normal renal function or nondiabetic wild-type mice. This pattern suggests alterations in chromatin structure that favor gene transcription. In fact, hearts from uninephrectomized db/db mice revealed increased mRNA expression of multiple cardiomyopathy-related genes together with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. These data suggest that renal failure alters cardiac histone H3 epigenetics, which foster cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in type 2 diabetes.

Early diabetic nephropathy, affecting more than 30% of diabetes patients, is characterized by glomerular hyperfiltration and increased production of extracellular matrix but tends to progress to diffuse glomerulosclerosis, proteinuria, and renal failure.1 Proteinuria and renal failure are two independent risk factors for cardiovascular complications in type I and type II diabetes.2 Diabetic cardiomyopathy is characterized by cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, perivascular or interstitial fibrosis, and interstitial accumulation of glycoprotein.3 The molecular pathways that link renal failure to progression of cardiac disease remain unclear. Several studies have proposed a role of hypertension,4 dyslipidemia,5 activation of the renin-angiotensin system,6 endothelial dysfunction,7 oxidative stress,8 and inflammation9 in this context. It is thought that all of these factors affect the function and finally the structure of the cardiac vasculature and cardiomyocytes by activating different signaling pathways that specifically drive transcription of downstream pathogenic factors.3

Histone epigenetics are now recognized as another level of gene transcription control because covalent histone modifications regulate chromatin dynamics like heterochromatin formation as a requirement for transcription factor binding.10,11 For example, histone deacetylase 5 reduces histone H3 acetylation and thereby impairs the expression of cardiomyocyte growth and remodeling genes.12 Furthermore, distinct histone H3 methylation patterns have been identified in left ventricular biopsies from humans with heart failure.13

We hypothesized that the metabolic abnormalities associated with renal failure might affect the cardiac histone H3 modification patterns and gene transcription beyond those observed by hyperglycemia alone.

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

Male 5-week-old C57BL/6 and C57BLKS db/db were obtained from Taconic (Ry, Denmark). At the age of 6 weeks uninephrectomy (1K mice) or sham surgery (2K mice) was performed as previously described.14 All experimental procedures had been approved by the local government authorities. Only db/db mice that revealed blood glucose levels >200 mg/dl (Accu check sensor, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were included in the study. Urinary albumin was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Bethyl Labs, Montgomery, TX) and urinary creatinine by Jaffé reaction (DiaSys Diagnostic Systems, Holzheim, Germany). Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was determined by clearance kinetics of plasma fluorescein isothiocyanate–inulin (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) 5, 10, 15, 20, 35, 60, and 90 minutes after a single bolus injection.15 Fluorescence was determined with 485 nm excitation and read at 535 nm emission. GFR was calculated based on a two-compartment model using a nonlinear regression curve-fitting software (GraphPad Prism, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Hearts and kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. The extent of glomerulosclerosis was assessed in 15 glomeruli per periodic acid-Schiff–stained section (Bio-Optica, Milano, Italy) using a semiquantitative score by a blinded observer as follows: 0 = no lesion, 1 = <25% sclerotic, 2 = 25% to 49% sclerotic, 3 = 50% to 74% sclerotic, 4 = 75% to 100% sclerotic, respectively. The number of cardiomyocyte nuclei was counted in each of 15 high-power fields.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was isolated from hearts using RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany). After reverse transcription with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) real-time RT-PCR was performed on a Light Cycler 480 (Roche) using Sybr Green PCR master mix and the primers as listed in Table 1. Gene expression values were normalized for respective 18s RNA expression.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used for Real-Time RT-PCR

| Gene name | Accession No. | MGI nomenclature | Primer sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myosin heavy chain 3 | NM_001099635 | Myh3 | Forward: 5′-GGAGAAGCTCGTCACTTTGG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-ATCGTTCCTCAGCATCCAAC-3′ | |||

| Myosin light chain 3 | NM_010859 | Myl3 | Forward: 5′-AGAGCCCAAGAAGGATGATG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CATCAAACTCGGCTTCCTTG-3′ | |||

| Tubulin alpha | NM_011653 | Tuba1a | Forward: 5′-TTGGTGTGGATTCTGTGGAA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-AAACATCCCTGTGGAAGCAG-3′ | |||

| Catenin alpha I | NM_009818 | Ctnna1 | Forward: 5′-CGTGAACATGCCAACAAACT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCACGCCTTCTTCATTGTTG-3′ | |||

| Collagenase (mmp1b) | NM_032007 | Mmp1b | Forward: 5′-TGCTATAATTACATATCGGGGG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CATCGATCAAAGGTTCTGGC-3′ | |||

| Collagen alpha I type II | NM_031163 | Col2a1 | Forward: 5′-CTACGGTGTCAGGGCCAG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GCAAGATGAGGGCTTCCATA-3′ | |||

| Integrin alpha I | NM_001033228 | Itga1 | Forward: 5′-ATGCCTTGTGTGAAGTTGGA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCCCTTCGGATTGGTGACTA-3′ | |||

| Laminin beta 2 | NM_008483 | Lamb2 | Forward: 5′-CATGTGCTGCCTAAGGATGA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCAGCTTGTAGGAGATGCCA-3′ | |||

| Plasminogen protein | NM_008877 | Plg | Forward: 5′-CCAGAGAACTTCCCAGATGC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-AGTATTCCCACCTGACGCTC-3′ | |||

| Protein tyrosin kinase (apoptosis-associated) | NM_007377 | Aatk | Forward: 5′-ATCAGCCCCTGCCTCTTT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CCAGAGAAGGACACGGCTAC-3′ | |||

| TGF beta 3 | NM_009368 | Tgfb3 | Forward: 5′-ATTCGACATGATCCAGGGAC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCTCCACTGAGGACACATTGA-3′ | |||

| NFkB | NM_008689 | Nfkb1 | Forward: 5′-CATCACACGGAGGGCTTC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GAACGATAACCTTTGCAGGC-3′ | |||

| NFKB activating protein | NM_025937 | Nkap (RIKEN) | Forward: 5′-GCGTATCCCAAGAAGAGGTG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GAAGTCGAACAGCCTCCATT-3′ | |||

| VEGFa | NM_001025250 | VEGFa | Forward: 5′-GTACCTCCACCATGCCAAGT-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-TCGCTGGTAGACATCCATGA-3′ | |||

| VEGFb | NM_011697 | VEGFb | Forward: 5′-GAGTGCTGTGAAGCCAGACA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GATGTCAGCTGGGGAGGAT-3′ | |||

| TNF | NM_013693 | TNF | Forward: 5′-CCACCACGCTCTTCTGTCTAC-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-AGGGTCTGGGCCATAGAACT-3′ | |||

| 18S | 18S | Forward: 5′-GCAATTATTCCCCATGAACG-3′ | |

| Reverse: 5′-AGGGCCTCACTAAACCATCC-3′ | |||

| Myosin alpha | NM_010856 | Myh6 | Forward: 5′-GCGCATTGAGTTCAAGAAGA-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-CTTCATCCATGGCCAATTCT-3′ | |||

| Myosin beta | NM_080728 | Myh7 | Forward: 5′-GAGTACCAGCGCATGCTAGG-3′ |

| Reverse: 5′-GACCAGTTCTTGACGGCATT-3′ |

MGI: Mouse Genome Informatics.

Histone Extraction and Immunoblotting

Hearts were manually dissected and histone isolation was performed as described.16 Three hearts were pooled from each group for histone isolation. Immunoblot analysis was performed by using anti-acetylated histone H3 at lysine 23 and 9 (rabbit 1:5000), anti-phosphorylated histone H3 at serine 10 (rabbit 1:5000), dimethylated histone H3 at lysine 4 and 9 (rabbit 1:5000), anti-histone H3 (rabbit 1:5000), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Proteins were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence system and enhanced chemiluminescence Hyperfilm (Amersham, Freiburg, Germany). Immunoblots were quantitated by densitometric analysis and the exposures were in linear dynamic range. The densitometry analysis was performed by Image J software, NIH, USA.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparison of groups was performed using Student t test and one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunnett test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Early Uninephrectomy Increases Albuminuria and Reduces GFR in db/db Mice

Early uninephrectomy induces glomerular hyperfiltration, which enhances the progression of diabetic glomerulosclerosis in male db/db mice.14 As such early uninephrectomy increased the glomerulosclerosis score and albuminuria and reduced GFR in 6-month-old db/db mice (Table 2). By contrast, uninephrectomy did not affect body weight or plasma glucose levels (Table 2). Hence, uninephrectomized male db/db mice represent a model of type 2 diabetes with diffuse glomerulosclerosis, albuminuria, and renal failure.

Table 2.

Early Uninephrectomy Accelerates Kidney Disease in db/db Mice

| B6 2K | B6 1K | db/db 2K | db/db 1K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, g | 27 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 58 ± 3 | 56 ± 3 |

| Heart weight (HW), mg | 127 ± 2 | 141 ± 6 | 135 ± 3 | 131 ± 4 |

| HW/body weight ratio | 4.7 ± 0.13 | 4.7 ± 0.11 | 2.4 ± 0.06 | 2.4 ± 0.07 |

| Plasma glucose, mg/dl | 142 ± 4 | 166 ± 3 | 414 ± 22††† | 399 ± 25††† |

| Urinary albumin to creatinine ratio | 0.08 ± 0.02 | ND | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.03* |

| GFR, ml/min | 385 ± 103 | ND | 293 ± 74 | 116 ± 22**††† |

| Glomerulosclerosis score | 0.14 ± 0.1 | ND | 1.98 ± 0.19†† | 2.91 ± 0.24**††† |

All the values were represented as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

***P < 0.001, significantly different from db/db mice.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.001, significantly different from B6 mice. 2K=sham operated, 1K=uninephrectomized, ND indicates not done.

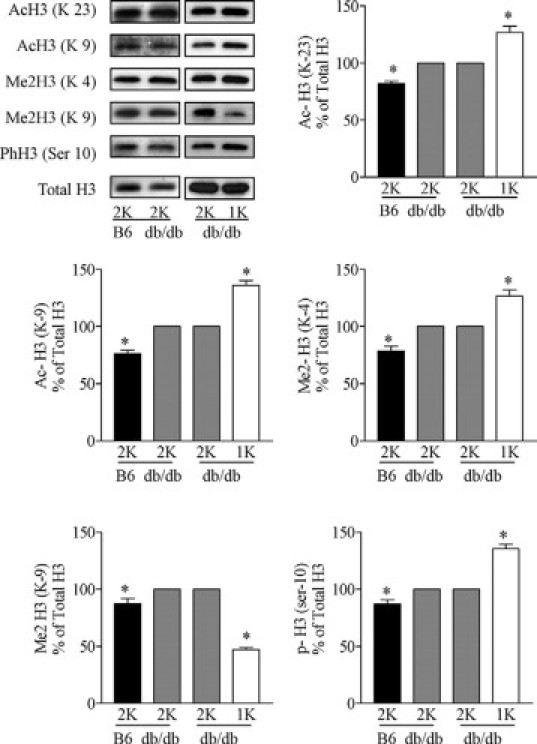

Renal Failure Affects Epigenetic Histone H3 Modifications in Hearts of db/db Mice

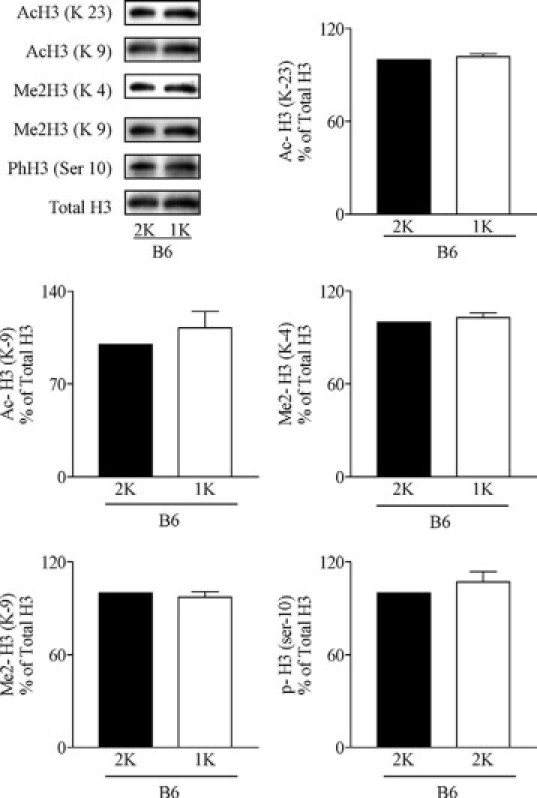

We used Western blotting of cardiac cell nuclei extracts to determine a number of specific covalent histone modifications. We first studied the impact of diabetes by comparing hearts of sham-operated C57BL/6 with those of sham-operated C57BLKS db/db mice at the age of 24 weeks. The latter showed increased H3 acetylation at lysine 9 and 23, H3 dimethylation at lysine 4 and 9, and H3 phosphorylation at serine 10 (Figure 1). Early uninephrectomy further increased H3 acetylation at lysine 9 and 23, H3 dimethylation at lysine 4, and H3 phosphorylation at serine 10 as compared with 2K db/db mice (Figure 1). We also observed a decrease in the H3 dimethylation at lysine 9 in 1K vs 2K db/db mice or wild-type mice (Figure 1). By contrast, none of these changes was observed in cardiac histone preparations from 1K wild-type mice (Figure 2). Hence, kidney disease in type 2 diabetic mice alters histone H3 epigenetics in a way that indicates transcriptionally active chromatin.

Figure 1.

Effect of uninephrectomy on cardiac histone H3 modifications in diabetic mice. H3 Acetylation (Lys 23 and 9), methylation (Lys 4 and 9), and phosphorylation (Ser 10) were determined by Western blot in heart histone isolates from sham-operated (2K) wild-type B6 mice, sham-operated (2K) db/db mice, and uninephrectomized (1K) db/db mice. Quantitative analysis is shown in arbitrary units where blots of 2K db/db mice are set as 100%. *P < 0.05 versus 2K db/db mice.

Figure 2.

Effect of uninephrectomy on cardiac histone H3 modifications in wild-type mice. H3 Acetylation (Lys 23 and 9), methylation (Lys 4 and 9), and phosphorylation (Ser 10) were determined by Western blot in heart histone isolates from sham-operated (2K) or uninephrectomized (1K) wild-type mice. Quantitative analysis is shown in arbitrary units where blots of 2K db/db mice are set as 100%. No statistically significant differences were detected.

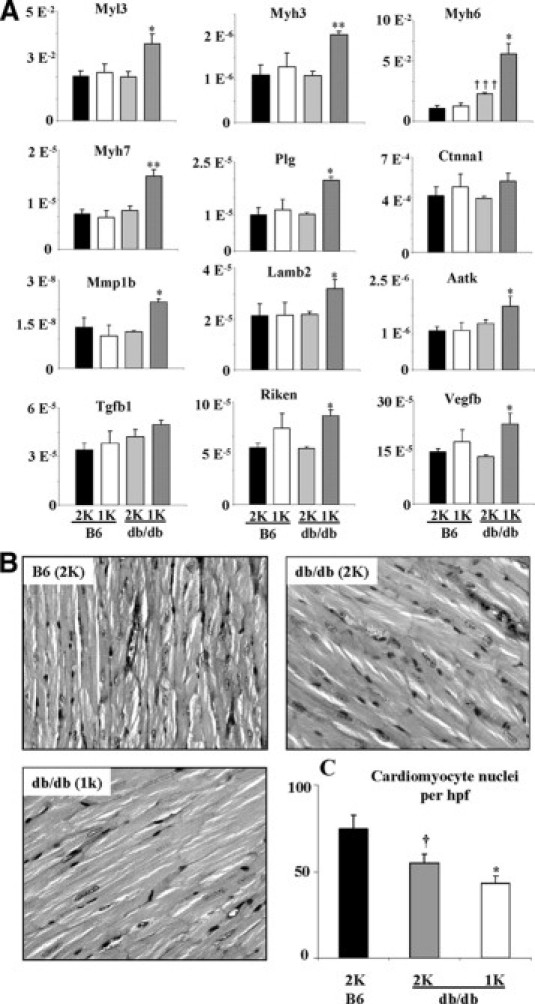

Renal Failure Enhances Cardiac mRNA Expression of Several Cardiomyopathy-Related Genes and Induces Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy in db/db Mice

Activation of cardiac chromatin may be associated with increased expression of cardiomyopathy-related genes. We found that the mRNA levels of myosin heavy chains 3, 6, and 7, myosin light chain 3, as well as tubulin-α, catenin-α1, and laminin-β2 were significantly increased in hearts of 1K versus 2K db/db mice (Figure 3A). This was associated with the induction of a number of additional genes known to be involved in tissue remodeling (eg, matrix metalloproteinase 1, plasminogen protein, Riken, and vascular endothelial growth factor β). By contrast, diabetes in 2K db/db mice did only affect α-MHC myosin heavy chain mRNA levels as compared with nondiabetic wild-type mice (Figure 3A). Next, we questioned whether the altered histone H3 modification pattern and the increased gene expression in hearts of 1K db/db mice would be associated with a distinct cardiomyocyte phenotype. To answer this question, we performed histomorphometrical analysis of crosssections of the anterior left ventricular wall and the interventricular septum from mice of all groups. In 6-month-old 1K db/db mice the number of cardiomyocyte nuclei in a given high-power field was significantly reduced as compared with age-matched 2K db/db mice, which was already significantly lower as compared with that of nondiabetic wild-type mice (Figure 3B). These data would support that renal failure increases cardiomyopathy-related gene expression and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy rather than cardiomyocyte proliferation. Heart weights and heart to body weight ratios did not significantly differ between 2K and 1K db/db mice (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Cardiac gene profiling and histopathology. A: The mRNA expression of cardiomyopathy-related genes was quantified using RT-PCR as described in Methods. All values represent means ± SEM. **P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05, significantly different from db/db (2K) mice; †††P < 0.01, significantly different from B6 (2K) mice (t test). B: Heart sections from mice of the different groups were stained with periodic acid-Schiff as described in Methods. C: The graph illustrates the mean percentage of number of nuclei ± SEM from all mice in each group (n = 6). *P < 0.05, significantly different from db/db (2K) mice; †P < 0.05, significantly different from B6 (2K) mice (t test).

Discussion

We found renal failure to be associated with increased cardiac histone H3K9 and H3K23 acetylation, H3K4 dimethylation, and phosphorylation at serine 10. The effect of renal failure adds to that of type II diabetes as the comparison of diabetic and nondiabetic mice already revealed a similar modification pattern. However, uninephrectomy did not affect cardiac histone epigenetics in wild-type mice, which may be a relevant finding in the context of living kidney donation. It is of interest that histone acetylation, H3K4 dimethylation, and phosphorylation at serine 10 lead to histone relaxation (ie, unwinding of the packed nucleosomes), which makes the DNA accessible for the binding of activated transcription factors that are translocated into the nucleus.10,11,17,18 By contrast, H3 dimethylation at lysine 9 promotes chromatin condensation, which suppresses transcription factor binding.11 H3 dimethylation at lysine 9 has recently been reported to be suppressed in bovine aortic endothelial cells after transient glucose exposure.19 We did not observe the same in hearts of db/db mice with persistent hypergylcemia but H3 dimethylation at lysine 9 was suppressed in 1K db/db mice. Together, the epigenetic histone H3 modification pattern observed in hearts of db/db mice with renal failure would predict increase in global gene expression (eg, in cardiomyocytes). We therefore analyzed the mRNA expression of cardiomyopathy-related genes because cardiomyocyte hypertrophy has been reported as one of the features of diabetic cardiomyopathy.3 Our finding that renal failure increased cardiac mRNA expression of most of these genes together with cardiomyocyte size in db/db mice might be a direct result of this specific epigenetic histone modification pattern. Yet it remains unclear which is the most relevant factor modulating histone epigenetics, and future work will need to determine how factors like arterial hypertension, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, obesity, proteinuria, and uremic toxins individually affect histone modifying enzymes. In addition, it will be necessary to see whether histone epigenetic-modulating drugs can prevent cardio-renal syndromes, like diabetic nephropathy-associated cardiomyopathy.20,21 Furthermore, it is likely that the observed changes do also occur in other organs affected by diabetes complications, a topic to be studied in the future.

Footnotes

Supported by the Deutscher Akademischer Auslandsdienst (DAAD) Ph.D., sandwich program (A.B.G.) and the EU integrated project INNOCHEM (Innovative Chemokine-based Therapeutic Strategies for Autoimmunity and Chronic Inflammation) to H.J.A.

A.B.G., S.G.S., K.T., and J.-J.A. contributed equally to this study.

References

- 1.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001;414:782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffrin EL, Lipman ML, Mann JF. Chronic kidney disease: effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2007;116:85–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poornima IG, Parikh P, Shannon RP. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: the search for a unifying hypothesis. Circ Res. 2006;98:596–605. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000207406.94146.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray DC, Barre PE. Impact of hypertension on cardiomyopathy, morbidity and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1996;49:1379–1385. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trevisan R, Dodesini AR, Lepore G. Lipids and renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:S145–S147. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005121320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schiffrin EL, Touyz RM. From bedside to bench to bedside: role of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in remodeling of resistance arteries in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H435–H446. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00262.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasdan G, Benchetrit S, Rashid G, Green J, Bernheim J, Rathaus M. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in 5/6 nephrectomized rats are mediated by vascular superoxide. Kidney Int. 2002;61:586–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaziri ND, Dicus M, Ho ND, Boroujerdi-Rad L, Sindhu RK. Oxidative stress and dysregulation of superoxide dismutase and NADPH oxidase in renal insufficiency. Kidney Int. 2003;63:179–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pecoits-Filho R, Heimburger O, Barany P, Suliman M, Fehrman-Ekholm I, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P. Associations between circulating inflammatory markers and residual renal function in CRF patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:1212–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhaumik SR, Smith E, Shilatifard A. Covalent modifications of histones during development and disease pathogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song K, Backs J, McAnally J, Qi X, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, Hill JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. The transcriptional coactivator CAMTA2 stimulates cardiac growth by opposing class II histone deacetylases. Cell. 2006;125:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaneda R, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Choi YL, Nonaka-Sarukawa M, Soda M, Misawa Y, Isomura T, Shimada K, Mano H. Genome-wide histone methylation profile for heart failure. Genes Cells. 2009;14:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ninichuk V, Kulkarni O, Clauss S, Anders HJ. Tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and inflammation in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. An accelerated model of advanced diabetic nephropathy. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12:351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ninichuk V, Clauss S, Kulkarni O, Schmid H, Segerer S, Radomska E, Eulberg D, Buchner K, Selve N, Klussmann S, Anders HJ. Late onset of Ccl2 blockade with the Spiegelmer mNOX-E36–3′PEG prevents glomerulosclerosis and improves glomerular filtration rate in db/db mice. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:628–637. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tikoo K, Meena RL, Kabra DG, Gaikwad AB. Change in post-translational modifications of histone H3, heat-shock protein-27 and MAP kinase p38 expression by curcumin in streptozotocin-induced type I diabetic nephropathy. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153:1225–1231. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Backs J, Olson EN. Control of cardiac growth by histone acetylation/deacetylation. Circ Res. 2006;98:15–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000197782.21444.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balasubramanyam K, Varier RA, Altaf M, Swaminathan V, Siddappa NB, Ranga U, Kundu TK. Curcumin, a novel p300/CREB-binding protein-specific inhibitor of acetyltransferase, represses the acetylation of histone/nonhistone proteins and histone acetyltransferase-dependent chromatin transcription. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51163–51171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409024200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brasacchio D, Okabe J, Tikellis C, Balcerczyk A, George P, Baker EK, Calkin AC, Brownlee M, Cooper ME, El-Osta A. Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that co-exist on the lysine tail. Diabetes. 2009;58:1229–1236. doi: 10.2337/db08-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berry JM, Cao DJ, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Histone deacetylase inhibition in the treatment of heart disease. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7:53–67. doi: 10.1517/14740338.7.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKinsey TA, Olson EN. Cardiac histone acetylation–therapeutic opportunities abound. Trends Genet. 2004;20:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]