Abstract

Sarcoidosis is a chronic disease of unknown etiology characterized by the formation of non-necrotizing epithelioid granulomas in various organs, especially in the lungs. The lack of an adequate animal model reflecting the pathogenesis of the human disease is one of the major impediments in studying sarcoidosis. In this report, we describe ApoE−/− mice on a cholate-containing high-fat diet that exhibit granulomatous lung inflammation similar to human sarcoidosis. Histological analysis revealed well-defined and non-necrotizing granulomas in about 40% of mice with the highest number of granulomas after 16 weeks on a cholate-containing high-fat diet. Granulomas contained CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and the majority of the cells in granulomas showed immunoreactivity for the macrophage marker Mac-3. Cells with morphological features of epithelioid cells expressed angiotensin-converting enzyme, osteopontin, and cathepsin K, all characteristics of epithelioid and giant cells in granulomas of human sarcoidosis. Giant cells and nonspecific inclusions such as Schaumann's bodies and crystalline deposits were also detected in some lungs. Granulomatous inflammation resulted in progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Removal of cholate from the diet prevented the formation of lung granulomas. The observed similarities between the analyzed mouse lung granulomas and granulomas of human sarcoidosis, as well as the chronic disease character leading to fibrosis, suggest that this mouse model might be a useful tool to study sarcoidosis.

Sarcoidosis is an enigmatic multisystem disorder characterized by the presence of non-necrotizing granulomas in multiple organs with a dominant pulmonary involvement. Incidence rates of sarcoidosis are estimated to be between 16.5 of 100,000 in men and 19 of 100,000 in women varying according to age, race, and geographic origin.1,2 Any organ can be affected in sarcoidosis, but more than 90% of patients have granulomatous infiltrations in lungs with respiratory symptoms such as dry cough, dyspnea, or bronchial hyperreactivity.3 In most patients, spontaneous resolution of granulomatous infiltrations occurs within 12 to 36 months, but up to 30% of patients have a chronic course of the disease. Long-lasting nontreated sarcoidosis results in progressive loss of lung function and destruction of lung architecture of the lower respiratory tract. Pulmonary fibrosis is the most frequent severe manifestation of sarcoidosis. It is characterized by a disproportional increase in extracellular matrix deposition and it is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in western countries. Mortality occurs in 1% to 5% of patients with sarcoidosis.4

Sarcoidosis has been known for more than 100 years; however, no single causative agent, host reaction, or autoantigen linked specifically to sarcoidosis has been confirmed.1,5,6 Current understanding of sarcoidosis pathogenesis is that infectious or noninfectious antigens induces a highly polarized Th1-immune response that induces the formation of granulomas.6–8 An infectious cause of sarcoidosis was proposed because the earliest description of the disease was based on histological similarities with tuberculosis. Recent studies revealed the presence of mycobacteria and propionobacteria in some patients with sarcoidosis.9 However, despite these studies a link between infectious agents and sarcoidosis remains controversial. In addition to the disease heterogeneity and elusiveness of causative agents, one of the major impediments to studying sarcoidosis is the lack of a widely accepted animal model that reproduces features of the human disease.10,11 In one of the first animal models, Kveim reagent (homogenates of human sarcoid tissues) injection was used to generate granulomatous inflammation in mice.5 The most common models of murine sarcoidosis exploit tail vein injections of Mycobacterium, Propionobacterium, or Schistosoma infection, but these models are focusing on the acute phase of granuloma formation and have different time frames when compared with human chronic persistent sarcoidosis.11,12

Here, we show that ApoE−/− mice on a cholate-containing high-fat diet (CHFD) develop non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas in lungs that resemble granulomas of human sarcoidosis in their morphology and cellular composition and are similar to the human disease progress into lung fibrosis.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals and Design

Six-week-old ApoE−/− mice (C57BL/6; the Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were switched from the normal chow diet to a CHFD: 18% lard fat, 1% cholesterol, and 0.5% sodium cholate (Purina Mills, LLC, St Louis, MO). After 8, 16, and 19 weeks of a CHFD, mice were sacrificed by exsanguination under xylazine-ketamine anesthesia. One group of mice received a high-fat diet but without sodium cholate (HFD) for 16 weeks. Control ApoE−/− mice on the normal diet were sacrificed at the age of 22 weeks. All experiments were approved by the regulatory authority of the University of British Columbia.

Tissue Preparation

After perfusion with ice-cold PBS, lungs, thymus, liver, stomach, and skin from the nape of the neck and upper back were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 5 hours at 4°C, embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were cut and mounted onto Superfrost/Plus slides (Fisher-Scientific, Ottawa, ON).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated, blocked with 10% goat serum in PBS, and incubated overnight at 4°C in 1% of bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffered saline with the following primary antibodies: affinity purified rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse cathepsin K (MS4; 1:50),13 mouse monoclonal antibody against smooth muscle cell α-actin (1:100; Biomeda, Foster City, CA), rat anti-mouse macrophage (Mac-3; 1:100; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-mouse osteopontin (1:100; American Research Products, Inc Belmont, MA), rabbit polyclonal anti-CD4 (1:100; Abbiotec, San Diego, CA), rabbit polyclonal anti-CD8 (1:100; AnaSpec, San Jose, CA), and goat polyclonal antiangiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) antibody (1:50; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA). For ACE staining, sections were blocked in 10% of donkey serum. As negative controls, rabbit, mouse, rat, or goat IgGs were used at the same dilutions as the appropriate primary antibodies. Tissue sections were then incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody: goat anti-rabbit Cy3-conjugated, goat anti-mouse Cy2-conjugated antibody (1:200; Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA), goat anti-rat fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and donkey anti-goat Texas Red-conjugated (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc, West Grove, PA).

Granuloma Cell Composition

The areas of granulomas stained positively for Mac-3, osteopontin, CD4, and CD8 were quantified by using color threshold and calculated as the percentage of total granuloma area. The images were captured by using a Leica DMI 6000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Inc, Richmond Hill, ON) and were analyzed by using Openlab 3 software (Improvision Ltd, Coventry, UK).

Gomori's Trichrome Staining

Sections were deparaffinized, hydrated with graded alcohol and distilled water, and then placed in preheated Bouin's solution at 58°C for 10 minutes. The slides were then washed in running water to remove the yellow color. Sections were stained in working Weigert's iron hematoxylin solution for 5 minutes, washed under running water for 30 seconds, stained with Gomori's trichrome solution (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 minutes, placed in 0.5% of acetic acid for 10 seconds, and then mounted for light microscopy.

Quantification of Pulmonary Fibrosis, Number of Granulomas, and Inducible Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Area

Five sections 200 μm apart from each other were analyzed for each lung. For pulmonary fibrosis assessment, a recently offered method for standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in murine model was used.14 Four pictures per lung section were made by using a 20-fold magnification avoiding areas with dominating tracheal or bronchial tissue. Fields were graded, added up, and divided by the number of fields. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) area was quantified as the percentage of total lung area. The average number of granulomas, fibrosis grade, and iBALT areas for each mouse were used for statistical analyses.

Hydroxyproline Assay

One hundred microliters of lung homogenates were hydrolyzed in 100 μl of HCl at 105°C overnight. Samples were analyzed for hydroxyproline by using chloramine-T as previously described,15 and hydroxyproline content was calculated as microgram hydroxyproline/mg protein.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid

Lungs were lavaged in situ five times with 1 ml of saline, and 3 to 4 ml of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid were recovered. The BAL fluid was centrifuged, and sedimented cells were washed three times with PBS containing 1% of bovine serum albumin. Rat anti-mouse CD4-Alexa 488 at a final concentration of 3 μg/ml and rat anti-mouse CD8-phycoerythrin at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml were added, and samples were incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Primary labeled antibodies were obtained from the antibody facility at the University of British Columbia. Cells were washed three times and resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold PBS with 10% of fetal bovine serum. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a BD FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The 488-nm laser was used to excite Alexa 488 (530/40) and phycoerythrin (575/30). Data analysis was performed by using the Flowjo program (Tree Star, Inc, Ashland, OR) and was presented as CD4/CD8 ratio.

Human Tissue Samples

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue samples from five patients with sarcoidosis were selected from archives of Carl-Thiem-Klinikum (Cottbus, Germany). Two sections were from lungs, two were from lymph nodes, and one was from skin/nose. Table 1 summarizes the gender, age, and anatomical origin of the samples.

Table 1.

Human Tissues from Patients with Sarcoidosis

| Case no. | Age, years | Sex | Tissue/localization |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 55 | Female | Lung/right |

| 2 | 44 | Male | Lung/bronchus |

| 3 | 25 | Female | Lymph node/mediastinal |

| 4 | 40 | Female | Lymph node/mediastinal |

| 5 | 40 | Female | Skin/nose |

Statistical Analysis

Student's t-tests were performed, and data are presented as means ± SD. Significance was concluded when P < 0.05.

Results

Cholate-Containing High-Fat Diet Induces the Formation of Granulomas in Lungs of ApoE−/− Mice with Characteristic Features of Granulomas in Human Sarcoidosis

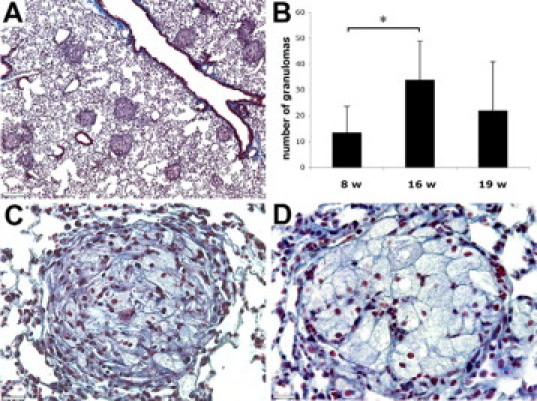

The histopathological hallmark of sarcoidosis is the presence of non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas with compact appearance and sharp boundaries from the surrounding lung tissues.16 ApoE−/− mice on CHFD developed well-formed granulomas in lungs that were diffusely distributed without angio- or bronchocentricity (Figure 1A). Granulomas were present in lungs of around 40% of the mice, and their numbers increased from around 12 at 8 weeks on CHFD to more than 30 per lung section after 16 weeks of diet (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Trichrome staining revealed non-necrotizing granulomas with sharp borders. Mice lungs after 16 weeks of CHFD (A), average number of granulomas per lung tissue section (B), tight fibrotic lung granuloma with abundant collagen fibers (C), and less fibrotic granuloma with more prominent epithelioid cells (D) are shown. Scale bars: 260 μm (A); 40 μm (C and D). *P < 0.05.

The core of the granulomas was formed by epithelioid cells. These cells were distinguished by their large size and polygonal shape with prominent cytoplasm (Figure 1, C and D). The majority of lungs granulomas were visible as dark ball-like structures because of a high collagen content as revealed by trichrome staining (Figure 1C), whereas others had a lighter appearance with easily recognizable epithelioid cells (Figure 1D). These differences may reflect different stages of granuloma maturation.

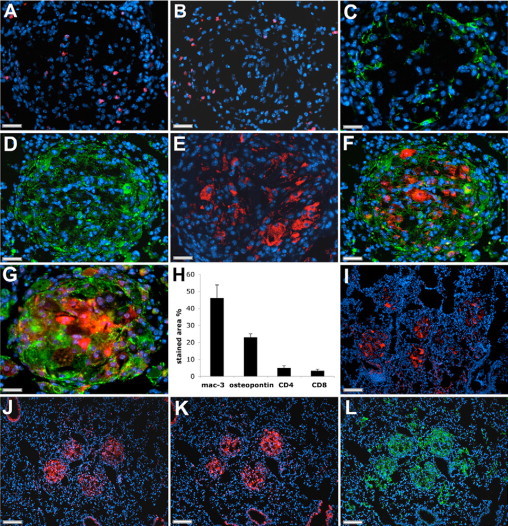

The activation of T-cells is mandatory for the development of granulomas.7 In sarcoidosis, CD4+ lymphocytes are predominant and a smaller number of CD8+ T-cells are typically present in the periphery of granulomas.12,17 We observed a similar distribution of CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Figure 2, A and B) present in 5% and 3.3% of the area of granulomas, respectively (Figure 2H). Fibroblasts were observed in the perimeter of some granulomas (Figure 2C). Nonlymphoid mononuclear cells were the dominant cellular constituents in all granulomas. Immunostaining for macrophage marker Mac-3 showed that about 45% of the granuloma-encompassing areas were Mac-3-positive (Figure 2, D and H) with the strongest staining at the periphery. On the contrary, proteins such as ACE, osteopontin, and cathepsin K revealed strong expression in large cells at the core of the granulomas (Figure 2, E–G). These three proteins are highly expressed in epithelioid and giant cells of human granulomas of sarcoidosis.18–21 Osteopontin-stained areas occupied 23% of the total granulomas area (Figure 2H). The predominant expression of epitheloid cell-specific proteins such as ACE, osteoponin, and cathepsin K in granulomas is clearly visible in Figure 2, I–K, whereas the expression of macrophage marker, Mac-3, is not limited to granulomas (Figure 2L). Osteopontin and cathepsin K staining showed similar distribution in granulomas but only a weak colocalization with the macrophage marker, Mac-3 (Figure 2, F and G).

Figure 2.

Cellular characterization of granulomas in mouse lungs. (A) CD4 expression, (B) CD8 expression, (C) myofibroblast marker (smooth muscle cell α-actin) expression, (D) macrophage marker (Mac-3) expression, (E) angiotensin-converting enzyme expression, (F) osteopontin expression (red) with Mac-3 co-staining (green), (G) cathepsin K expression (red) with Mac-3 co-staining (green) are shown. ACE, osteopontin, and cathepsin K appear to be most strongly expressed in epitheliod cells. H: Percentage of granuloma area stained positive for macrophage marker (Mac-3), osteopontin, highly expressed in epithelioid cells, and T-cell markers is shown. Lower magnification of lung granulomas shows the predominant expression of ACE (I), osteopontin (J), cathepsin K (K), and the macrophages marker, Mac-3, within granulomas (L). Scale bars: 40 μm (A–G); 130 μm (I–L).

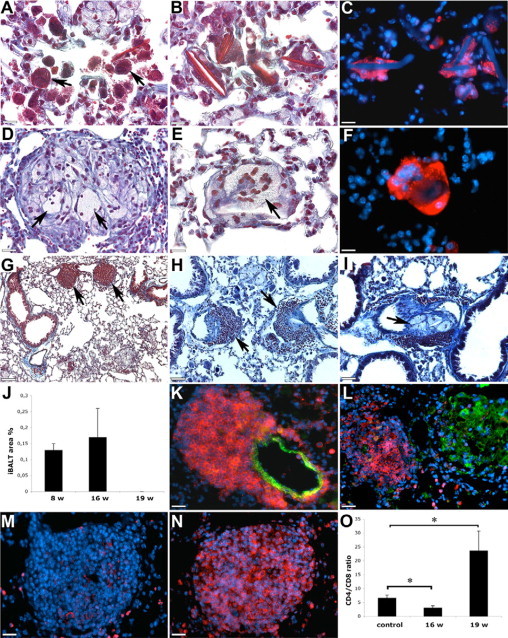

In addition to granulomas, some mice have shown the presence of inclusions such as Schaumann's bodies and calcium oxalate crystals that are frequently observed in lungs of patients with sarcoidosis.17 Schaumann's bodies have a conchoidal shape and contain calcium carbonate, iron, and oxidized lipids that are responsible for their dark and multihued appearance (Figure 3A). Schaumann's bodies have shown similarities in shape to epithelioid cells suggesting they originate from this cell type. Calcium oxalate crystals with iron accumulation can occur both inside and outside of Schaumann's bodies and giant cells.17,22 We observed crystals with brown appearance, most likely because of the presence of calcium oxalate and iron, close to Schaumann's bodies (Figure 3B). They were also found inside and adjacent to giant multinucleated cells that were cathepsin K-positive (Figure 3C). However, Schaumann's bodies and crystal inclusions are not considered to be specific for sarcoidosis.

Figure 3.

In some mouse lungs, Schaumann's bodies (A, arrows) and crystalline structures (B) were recognizable by a dark brown appearance in trichrome stained sections. Crystals were often observed inside of multinucleated giant cells with strong cathepsin K staining (C; red: cathepsin K; blue: nuclei and autofluorescence of crystals). Multinucleated giant cells were also present inside (D and E, arrows), and they were also cathepsin K-positive (F; red: cathepsin K; blue: nuclei). The presence of iBALTs in bronchovascular bundles (G and H, arrows) is shown. Occasionally granulomas were observed inside of blood vessels (I, arrow). The percentage of lung area occupied by iBALT (J) is shown. iBALTs consisted predominantly of CD8-cells and were attached to blood vessels (K; red: CD8; green: smooth muscle cell α-actin). Dense accumulation of CD8+ cells in iBALT and fewer Mac-3-positive cells in granulomas (L; red: CD8; green: Mac-3) are shown. Decreased amount of CD4+ (M; red: CD4) and the prevalence of CD8+ cells in iBALT (N; red: CD8) are shown. CD4/CD8 ratio in BAL fluid was decreased after 16 weeks and increased after 19 weeks of CHFD when compared with control mice (O). Scale bars: 20 μm (A–F); 130 μm (G); 65 μm (H and I); 30 μm (K–N). *P < 0.05.

Similar to human sarcoidosis, some granulomas contained multinucleated giant cells (Figure 3, D and E). Occasionally, multinucleated giant cells with strong cathepsin K expression were observed outside of granulomas (Figure 3F).

Granulomas of sarcoidosis tend to localize along bronchovascular bundles and pulmonary lymphatics, but they are also present in lung parenchyma.23 In our study, we have not observed any predominant distribution of granulomas, but mice developed iBALTs that were localized along bronchovascular bundles and close to blood vessels (Figure 3, G, H, and K). They were observed after 8 and 16 weeks of CHFD and disappeared after 19 weeks (Figure 3J). Occasionally, the presence of iBALT was accompanied by granulomas intruding blood vessels (Figure 3I) that might be similar to granulomatous vasculitis frequently observed in patients with sarcoidosis.23 iBALTs showed high cell densities with a predominance of CD8+ cells that clearly distinguished them from granulomas consisted of predominantly Mac-3-positive cells (Figure 3L). In contrast to CD8, CD4 staining was observed only in a few cells in iBALTs (Figure 3, M and N).

Flow cytometry analysis of BAL fluids revealed a twofold reduction of the CD4/CD8 ratio at 16 weeks of diet when compared with their littermates on the normal diet (Figure 3O). After 19 weeks of the cholate-containing diet, the CD4/CD8 ratio increased about 3.5-fold when compared with the controls.

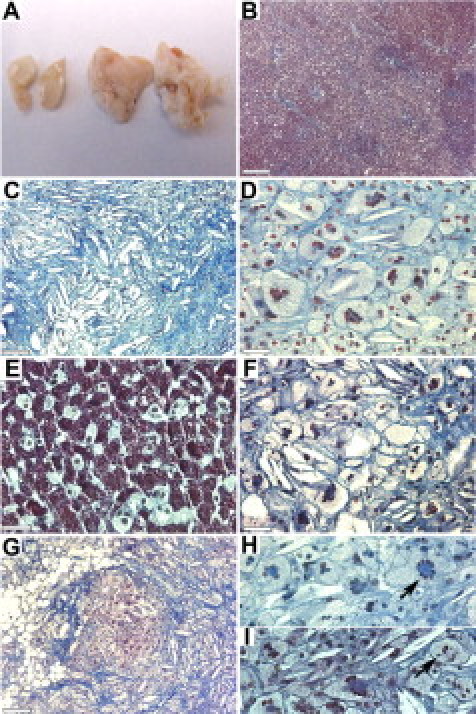

Extrapulmonary Involvement

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem disorder that can affect many organs. In addition to lungs, we analyzed skin, liver, heart, kidney, stomach, and thymus. At the later stages of the experiment (16 weeks of CHFD), mice developed xanthomas predominantly located at the neck and upper back areas where cutaneous lesions have been observed in human sarcoidosis.19 The thymus in all mice on CHFD revealed a striking hypertrophy (Figure 4A) with a more than threefold increase in thymus weight compared with mice on the normal diet after 16 and 19 weeks (with average wet weights of 34 ± 9 mg in the control group and 113 ± 42 mg and 112 ± 45 mg after 16 and 19 weeks of CHFD, respectively). Histological analysis revealed the presence of cholesterol clefts and a progressive development of fibrotic changes with an accumulation of collagen fibers and a honeycombing appearance with many multinucleated cells present (Figure 4, B–D). In the liver, lipid-filled hepatocytes were observed with some containing two to three nuclei per cell (Figure 4E). As for the thymus, cholesterol clefts, foreign body-type multinucleated cells, and an accumulation of collagen were also found in the stomach (Figure 4F). Xanthogranulomas were occasionally observed in skin lesions (Figure 4G) with Touton-like and foreign body type multinucleated giant cells (Figure 4, H and I). The presence of foreign body type and giant cells with Touton-like appearance has been previously described for cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis.24,25 Extrapulmonary phenotypes such as those observed in the skin and thymus did not allow us to determine whether a mice has granulomas because we did not observe differences in thymus weight and the occurrence of xanthomas between mice with or without lung granulomas that were on CHFD. This might be related to the resolution and reoccurrence of lung granulomas as it is described in sarcoidosis.1

Figure 4.

Organ pathology induced by CHFD. Cholate-containing diet induced hypertrophy in thymus and fibrosis and induced formation of MGCs in thymus, liver, stomach, and skin. After 16 weeks of CHFD, thymus size was significantly increased (A; left: 22-week-old mice on normal diet; right: 16 weeks of CHFD). Trichrome-stained sections of thymus in control mice (B) and highly fibrotic acellular thymus after 19 weeks on CHFD (C) are shown. Foreign body-type MGCs were observed in thymus (D) and stomach (F). Lipid-filled cells with two to three nuclei were seen in liver (E). Mice on prolonged CHFD developed skin lesions with xanthogranulomas (G). Touton-type MGCs with a central and circular distribution of nuclei (H, arrow) and foreign body-like MGCs (I, arrow) in skin sections were frequently observed. Scale bars: 130 μm (B, C, and G); 30 μm (E); 20 μm (D, F, H, and I).

Progressive Lung Fibrosis

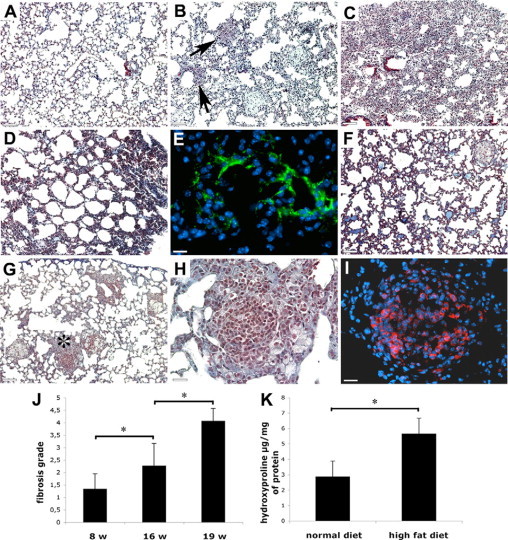

With aging, epithelioid cell granulomas undergo fibrosis and hyalinization. To estimate the rate of fibrosis, we used a method for standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in murine models.14 Feeding CHFD resulted in a progressive development of lung fibrosis (Figure 5, A–C). The fibrotic grade tripled from 8 to 19 weeks of CHFD (Figure 5J). After 16 weeks of CHFD, lungs of ApoE−/− mice contained individual isolated fibrotic masses with the development of hyaline membranes in some areas (Figure 5B). Lung areas with the highest degree of fibrotic changes contained confluent fibrotic masses (Figure 5C). As an additional marker for fibrosis, we determined the hydroxyproline content (biochemical collagen marker) in lungs and found a twofold increase after 16 weeks of HFD (Figure 5K). In some areas of lungs, we observed honeycombing structures (Figure 5D), which have been described in human sarcoidosis.17 In early fibrotic stages, myofibroblast foci were observed (Figure 5E) indicative for extracellular matrix production. Intraalveolar proteinaceous deposits were observed in some lungs providing evidence of acute lung injury (Figure 5F). At the later stages of the CHFD, granulomas were often surrounded by fibrotic tissue without visible changes in granuloma cell composition (Figure 5B). Some granulomas, however, revealed fibrotic changes inside their perimeter and were characterized by the presence of cells morphologically different from epithelioid cells (Figure 5, G and H) showing an unusually high amount of CD8+ cells (Figure 5I).

Figure 5.

Granulomatous inflammation resulted in progressive pulmonary fibrosis. Lung tissue section of a 22-week-old mice on normal diet (A), granulomas surrounded by single fibrotic masses and hyaline membranes after 16 weeks of CHFD (B, arrows show hyaline membranes), and confluent fibrotic masses after 9 weeks of CHFD (C) are shown. Fibrosis with honeycombing appearance (D) is shown. Immunostaining for smooth muscle cell α-actin revealed the presence of myofibroblasts foci (E) and the deposition of intraalveolar proteinaceous material as a result of acute lung injuries (F). In some cases granulomas were characterized by an unusual high cell density (G, asterisk shows area magnified in H) with the prevalence of CD8-positive cells (I). Quantification of fibrotic changes14 (J) is shown. Hydroxyproline content in lungs (K) is shown. Scale bars: 130 μm (A–D, F, and G); 20 μm (E); 30 μm (H and I). *P < 0.05.

Dietary Cholate and ApoE Deficiency are Essential for the Development of Granulomas

To reveal the cause responsible for granulomas formation, we compared mice after 16 weeks on HFD or CHFD because at this time point we observed the highest amount of granulomas. Diet lacking sodium cholate did not induce granuloma formation in any of the eight mice but induced lung fibrosis (grade 1.4 ± 0.5) that was comparable with the fibrosis after 8 weeks on CHFD. Mice on HFD did not show thymus hypertrophy and skin xanthomas as seen on the CHFD diet. Moreover, results with wild-type DBA/1J mice on 16 weeks on CHFD did not reveal the presence of lung granulomas (data not shown). This may suggest that the presence of sodium cholate in HFD and apolipoprotein E-deficiency are essential for granuloma formation.

Human Sarcoidosis

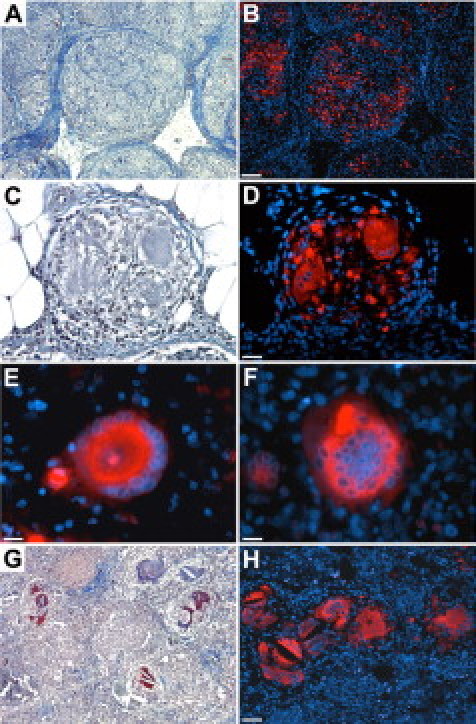

Immunohistochemical analysis of human sections with lung sarcoidosis revealed that similar to mouse lung granulomas, cathepsin K was present in epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells. Some granulomas contained only epithelioid cells (Figure 6, A and B), whereas in others, both types of cells were present (Figure 6, C and D). Cathepsin K-positive multinucleated giant cells, with either a circular arrangement of nuclei (Langhans type, Figure 6E) or a random distribution of nuclei (foreign body type, Figure 6F), were easily recognizable in areas of granulomatous inflammation. Similar to mouse lungs, giant multinucleated cells were seen adjacent to inclusions with dark brown appearance, most likely because of the presence of calcium salts and iron deposits (Figure 6, G and H).

Figure 6.

Human tissue sections from patients with sarcoidosis show similar characteristics regarding cathepsin K expression in granulomas as described in mice in this report. Epithelioid cells in skin granulomas (A, H&E staining) are cathepsin K immunoreactive (B), lymph node granuloma with epithelioid and giant cells (C, H&E staining) containing strong cathepsin K staining (D). Cathepsin K-positive Langhans-type MGC in lymph node (E) and foreign body-like MGC in lung (F) are shown. Crystals and inclusions with dark brown appearance (G, H&E staining) were often seen adjacent or within cathepsin K-positive MGCs (H) in sections with lung sarcoidosis. Scale bars: 130 μm (A, B, G, and H); 30 μm (C and D); 20 μm (E and F).

Discussion

Although sarcoidosis has been known for more than 100 years, the cause of this disease remains a mystery.5 Epithelioid granulomas are a hallmark of sarcoidosis. Their similarities to tuberculoid granulomas resulted in the hypothesis linking mycobacterial infection with sarcoidosis.6,9 However, in our experiment mice were kept in a pathogen-free facility and the granulomas appeared to be non-necrotizing thus eliminating the possible involvement of a Mycobacteria infection.

Granulomas in human sarcoidosis are formed by macrophages, epithelioid cells, lymphocytes, and occasionally by multinucleated giant cells and fibroblasts. 7,12,17,26 The lymphocytes present in granulomas are predominantly CD4+, whereas CD8+ cells are usually present in smaller numbers.12,26 The cell composition of granulomas found in lungs of ApoE−/− mice shows a high similarity to human granulomas of sarcoidosis.

Epithelioid and giant cells are specialized members of the monocyte/macrophage lineage that compose the core of epithelioid granulomas.27 Epithelioid cells have a prominent rough endoplasmic reticulum and a complex Golgi suggesting that epithelioid cells change from a phagocytic to a secretory phenotype. One of the proteins secreted by epithelioid cells in granulomas of sarcoidosis is ACE, and serum levels of this enzyme have been shown to be elevated in 60% of patients with sarcoidosis.18,19 Angiotensin II generated by ACE promotes lung injury and conversion of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts followed by the accumulation of collagen.28,29 Epithelioid cells in lung granulomas of ApoE−/− mice have shown strong ACE immunoreactivity that, similar to human granulomas, may contribute to the development of fibrotic changes in lungs.

Recently, immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization analyses have shown that cathepsin K might be a marker of macrophage differentiation toward epithelioid and giant cells.20 Our results support this notion because cathepsin K immunoreactivity in epithelioid and giant cells was highly elevated in lung granulomas.

In addition to ACE and cathepsin K expression, epithelioid cells in murine lung granulomas showed a strong staining for osteopontin, an extracellular matrix protein that is also known as an early T-lymphocyte activation gene-1 and a cytokine that is important for Th1 immunity.30,31 Th1 immune response mediated by CD4+ T-cells is activated in sarcoidosis and responsible for the initiation of granulomas formation.7,8,19 Osteopontin is one of the most prominently expressed proteins in giant and epithelioid cells in sarcoidosis.21 Recently it was shown that osteopontin can be cleaved by thrombin and several metalloproteinases.30 Thrombin-mediated cleavage of osteopontin generates amino- and carboxyl-terminal fragments of similar size but with different biological activities. The amino-terminal fragment appears to enhance cell adhesion and migration, whereas the carboxyl-terminal fragment suppresses the ability of full-length osteopontin to mediate cell adhesion and thus may prevent the development of granulomas in the lungs.32,33 On the other hand, full-length osteopontin showed an inhibitory activity on foreign body-type multinucleated cell formation.34 This may indicate that proteolytic posttranslational modifications of osteopontin modulate the formation of epitheloid and giant cells. The co-expression of osteopontin and cathepsin K in mouse and human granulomas suggests that cathepsin K might be implicated in osteopontin processing and therefore may play a part in the regulation of sarcoidosis development through the generation of physiologically active fragments of osteopontin and thus promoting epitheloid and giant cell formation.

An increase of the CD4/CD8 ratio in BAL fluid is a clinically important marker of sarcoidosis,8 but we observed a decrease in this ratio after 16 weeks when compared with control mice. This apparent contradiction to the human situation could be explained by the increased presence of iBALT composed predominantly of CD8+ cells at this time point. When iBALT disappeared after 19 weeks of HFD, the CD4/CD8 ratio increased almost fourfold compared with control mice. These results suggest that flow cytometric analysis was unable to detect an increase in the CD4/CD8 ratio because of the prevalence of CD8+ cells in iBALT at early stages of our experiment, despite the predominance of CD4+ cells in granulomas.

The formation of iBALT is rare in mice but occasionally may be induced in response to pulmonary infections and inflammatory reactions.35 iBALT is found in some patients with interstitial lung disease.36 It has been shown that iBALT can functionally replace the function of conventional lymphoid organs and its size and cell composition varies widely.37,38 Thus, the appearance of iBALT in our experiment might be related to the observed hypertrophy and fibrotic changes in thymus.

Pulmonary fibrosis occurs in 20% to 25% of patients with sarcoidosis and it is the most frequent cause of respiratory failure that results in deaths related to sarcoidosis.1,4,19,39 Primary effector cells in fibrosis are myofibroblasts. These cells possess characteristics of both fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. Myofibroblasts are extracellular matrix protein-producing cells with a contractile phenotype expressing α-smooth muscle cell actin.40

Granulomas in sarcoidosis tend to undergo perigranulomatous fibrotic changes, which is in accordance with our observed distribution of myofibroblasts in some granulomas and the development of fibrosis around late stage granulomas in mice fed on CHFD.

The pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis in patients with sarcoidosis remains poorly characterized, but it is known that the resolution of granulomas or the persistence of granulomatous inflammation leading to fibrosis development depend on the balance between Th1/Th2 cytokines.12,19,26 In an experiment with cholate-contained high-fat diet similar to our experiment, it was shown that ApoE−/− mice had shifted from a Th1 to a Th2 response.41 Th2 cells produce mainly interleukins 4, 10, and 13, which might be responsible for the differentiation of macrophages into epithelioid and giant cells. It was shown that mouse macrophages in the presence of interleukin-4 differentiate into epithelioid cells.42 It was further demonstrated that interleukin-4 induces the alternative activation of macrophages and their fusion into multinucleated giant cells and subsequently drives the development of lung fibrosis.43,44 It is tempting to speculate that the observed formation of multinucleated giant cells in several organs of mice and granulomatous inflammation in lungs during CHFD might be a result of such a shift to a Th2 response.

In conclusion, morphological and cell composition similarities between lung granulomas in ApoE−/− mice on a cholate-contained high-fat diet and granulomas observed in human sarcoidosis as well as their similar progression into a fibrotic stage suggest that this mouse model is useful for studying the mechanism of granulomas formation. The chronic and progressive granulatomous inflammation described in this model constitutes an improvement to current models based on acute phase of granuloma induction.

Footnotes

Supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research grant MOP24447. D.B. was supported by the Canada Research Chair award.

References

- 1.Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D. Sarcoidosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:46. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verleden GM, du Bois RM, Bouros D, Drent M, Millar A, Muller-Quernheim J, Semenzato G, Johnson S, Sourvino G, Olivier D, Pietinalho A, Xaubet A. Genetic predisposition and pathogenetic mechanisms of interstitial lung diseases of unknown origin. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;32:17S–29S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lynch JP, 3rd, Ma YL, Koss MN, White ES. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:53–74. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagai S, Handa T, Ito Y, Ohta K, Tamaya M, Izumi T. Outcome of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma OP. Sarcoidosis: a historical perspective. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moller DR. Potential etiologic agents in sarcoidosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:465–468. doi: 10.1513/pats.200608-155MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zissel G, Prasse A, Muller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis–immunopathogenetic concepts. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:3–14. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grunewald J, Eklund A. Role of CD4+ T cells in sarcoidosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:461–464. doi: 10.1513/pats.200606-130MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:365–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brass DM, Tomfohr J, Yang IV, Schwartz DA. Using mouse genomics to understand idiopathic interstitial fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007;4:92–100. doi: 10.1513/pats.200607-147JG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altmann DM, Boyton RJ. Model of sarcoidosis. Drug Discov Today Dis Models. 2006;3:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noor A, Knox KS. Immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia L, Kilb J, Wex H, Lipyansky A, Breuil V, Stein L, Palmer JT, Dempster DW, Brömme D. Localization of rat cathepsin K in osteoclasts and resorption pits: inhibition of bone resorption cathepsin K-activity by peptidyl vinyl sulfones. Biol Chem. 1999;380:679–687. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubner RH, Gitter W, El Mokhtari NE, Mathiak M, Both M, Bolte H, Freitag-Wolf S, Bewig B. Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples. Biotechniques. 2008;44:507–511. doi: 10.2144/000112729. 514–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Z, Hou WS, Bromme D. Collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is specifically modulated by cartilage-resident chondroitin sulfates. Biochemistry. 2000;39:529–536. doi: 10.1021/bi992251u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers JL, Tazelaar HD. Challenges in pulmonary fibrosis: 6–Problematic granulomatous lung disease. Thorax. 2008;63:78–84. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.031047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y, Gal A, Koss MN. The pathology of pulmonary sarcoidosis: update. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2007;24:150–161. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stanton LA, Fenhalls G, Lucas A, Gough P, Greaves DR, Mahoney JA, Helden P, Gordon S. Immunophenotyping of macrophages in human pulmonary tuberculosis and sarcoidosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2003;84:289–304. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2003.00365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iannuzzi MC, Rybicki BA, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buhling F, Reisenauer A, Gerber A, Kruger S, Weber E, Bromme D, Roessner A, Ansorge S, Welte T, Rocken C. Cathepsin K: a marker of macrophage differentiation? J Pathol. 2001;195:375–382. doi: 10.1002/path.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Regan A. The role of osteopontin in lung disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:479–488. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghio AJ, Roggli VL, Kennedy TP, Piantadosi CA. Calcium oxalate and iron accumulation in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:140–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen Y. Pathology of sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:36–52. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamoto H, Mizuno K, Horio T. Langhans-type and foreign-body-type multinucleated giant cells in cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:171–174. doi: 10.1080/00015550310007148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drummond C, Savdie E, Kossard S. Sarcoidosis with prominent giant cells. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:290–293. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2001.00539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerke AK, Hunninghake G. The immunology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:379–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.014. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popper HH. Epithelioid cell granulomatosis of the lung: new insights and concepts. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:32–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuba K, Imai Y, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in lung diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, Huan Y, Guo F, Guan B, Yang P, Sarao R, Wada T, Leong-Poi H, Crackower MA, Fukamizu A, Hui CC, Hein L, Uhlig S, Slutsky AS, Jiang C, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scatena M, Liaw L, Giachelli CM. Osteopontin: a multifunctional molecule regulating chronic inflammation and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2302–2309. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Denhardt DT, Giachelli CM, Rittling SR. Role of osteopontin in cellular signaling and toxicant injury. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda K, Takahashi K, Takahashi F, Tamura N, Maeda M, Kon S, Uede T, Fukuchi Y. Distinct roles of osteopontin fragments in the development of the pulmonary involvement in sarcoidosis. Lung. 2001;179:279–291. doi: 10.1007/s004080000068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Regan AW, Nau GJ, Chupp GL, Berman JS. Osteopontin (Eta-1) in cell-mediated immunity: teaching an old dog new tricks. Immunol Today. 2000;21:475–478. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01715-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai AT, Rice J, Scatena M, Liaw L, Ratner BD, Giachelli CM. The role of osteopontin in foreign body giant cell formation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5835–5843. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kocks JR, Davalos-Misslitz AC, Hintzen G, Ohl L, Forster R. Regulatory T cells interfere with the development of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue. J Exp Med. 2007;204:723–734. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rangel-Moreno J, Hartson L, Navarro C, Gaxiola M, Selman M, Randall TD. Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in patients with pulmonary complications of rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3183–3194. doi: 10.1172/JCI28756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiley JA, Richert LE, Swain SD, Harmsen A, Barnard DL, Randall TD, Jutila M, Douglas T, Broomell C, Young M. Inducible Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue elicited by a protein cage nanoparticle enhances protection in mice against diverse respiratory viruses. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyron-Quiroz JE, Rangel-Moreno J, Kusser K, Hartson L, Sprague F, Goodrich S, Woodland DL, Lund FE, Randall TD. Role of inducible bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (iBALT) in respiratory immunity. Nat Med. 2004;10:927–934. doi: 10.1038/nm1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bargagli E, Mazzi A, Rottoli P. Markers of inflammation in sarcoidosis: blood, urine BAL, sputum, and exhaled gas. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:445–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.004. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White ES, Lazar MH, Thannickal VJ. Pathogenetic mechanisms in usual interstitial pneumonia/idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Pathol. 2003;201:343–354. doi: 10.1002/path.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Paulsson G, Stemme S, Hansson GK. Hypercholesterolemia is associated with a T helper (Th) 1/Th2 switch of the autoimmune response in atherosclerotic apo E-knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1717–1725. doi: 10.1172/JCI1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cipriano IM, Mariano M, Freymuller E, Carneiro CR. Murine macrophages cultured with IL-4 acquire a phenotype similar to that of epithelioid cells from granulomatous inflammation. Inflammation. 2003;27:201–211. doi: 10.1023/a:1025084413767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helming L, Gordon S. The molecular basis of macrophage fusion. Immunobiology. 2007;212:785–793. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]