Abstract

Entamoeba histolytica is the protozoan parasite that causes amebic colitis. The parasite triggers apoptosis on contact with host cells; however, the biological significance of this event during intestinal infection is unclear. We examined the role of apoptosis in a mouse model of intestinal amebiasis. Histopathology revealed that abundant epithelial cell apoptosis occurred in the vicinity of amoeba in histological specimens. Epithelial cell apoptosis occurred rapidly on co-culture with amoeba in vitro as measured by annexin positivity, DNA degradation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Administration of the pan caspase inhibitor ZVAD decreased the rate and severity of amebic infection in CBA mice by all measures (cecal culture positivity, parasite enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and histological scores). Similarly, caspase 3 knockout mice on the resistant C57BL/6 background exhibited even lower cecal parasite antigen burden and culture positive rates than wild type mice. The permissive effect of apoptosis on infection could be tracked to the epithelium, in that transgenic mice that overexpressed Bcl-2 in epithelial cells were more resistant to infection as measured by cecal parasite enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and histological scores. We concluded that epithelial cell apoptosis in the intestine facilitates amebic infection in this mouse model. The parasite's strategy for inducing apoptosis may point to key virulence factors, and therapeutic maneuvers to diminish epithelial apoptosis may be useful in amebic colitis.

Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite and the causative agent of amebic colitis, an invasive disease responsible for as many as 100,000 deaths per year worldwide.1 The parasite proceeds from asymptomatic infection to invasive disease in a fraction of individuals, whereby it has been named “histolytica” for its cell-damaging properties.2 The cellular mechanism of this damage has been a subject of considerable study in which investigators use several nonepithelial cell types. Most of these results support the notion that Entamoeba directly triggers host cell apoptosis on contact as indicated by characteristic morphological changes (chromatin condensation, membrane blebbing, and internucleosomal DNA fragmentation), DNA laddering, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling positivity, and phosphatidylserine exposure3–9; however, one study revealed that a necrotic pathway can predominate.10 These studies have been performed by using cell lines including Jurkat T cells, HL-60 granulocytes, follicular dendritic cell protein 1, and Chinese hamster ovary cells, using primary human neutrophils, macrophages, erythrocytes, and T lymphocytes, and in a mouse amebic liver abscess model. Under the conditions of these studies, the apoptotic mechanism that occurs has been reported to be not inhibitable by Bcl-2 overexpression (in a myeloid cell line3), to not require Fas/Fas ligand or tumor necrosis factor receptor1 signaling (in mouse liver abscess8), to involve caspase 3 but not require caspase 8 or 9 (in Jurkat T cells5), and to require activation of extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 (in human neutrophils4).

Amid this context little is known about the extent of apoptosis in the intestinal epithelial cell, even though this is the first and predominant cell that contacts the parasite in the gut. Reasons for this lack of study are technical challenges in animal models of intestinal amebiasis11 and in establishing epithelial cell lines from colonic epithelium.12 For these reasons we developed a new conditionally immortalized cecal epithelial cell line derived from the CBA mouse and tested the role of intestinal epithelial apoptosis in vivo by using our CBA mouse model of intestinal infection.

Materials and Methods

Parasites

Trophozoites for in vitro assays were laboratory strain HM1:IMSS (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and were grown axenically and maintained in TYI-S-33 medium as previously reported.13,14 Trophozoites for intracecal injections were sequentially passaged through the mouse cecum and cultivated in antibiotic-supplemented TYI-S-33 medium as previously described.13

Mice

CBA/J mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). FVB-Bcl-2Tg mice were obtained from Craig Coopersmith (Washington University, St Louis, MO) and have been previously described.15 Caspase-3-deficient mice16 were obtained from Richard Hotchkiss (Washington University). Animals were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the University of Virginia and were challenged at 6 to 10 weeks of age under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols. For caspase inhibition studies before challenge, male CBA/J mice were injected intraperitoneally twice before challenge (days −3 and −1) and thrice after challenge (days +1, +3, and +5) with 100 μl of 10 μmol/L ZVAD-fmk (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or PBS/DMSO control. For caspase inhibition studies in mice with established infection, male CBA/J mice with laparotomy and cecal culture confirmed infection at 7 days after challenge were injected intraperitoneally on days +17, +20, and +22 with 100 μl of 200 μmol/L ZVAD-fmk or PBS/DMSO control before sacrifice on day +27. FVB-Bcl-2Tg and caspase-3-deficient mice were maintained as heterozygote breeding pairs. Genotype status was determined by PCR on genomic DNA extracted from ∼2-mm tail snips. For caspase-3-deficient mice, primer sequences used to determine the presence of the endogenous caspase 3 gene (primers 1 and 2) versus neomycin cassette (primers 3 and 4) were as follows: primer 1: 5′-TCCCTAAAAATGGTTCCAAATG-3′; primer 2: 5′-CTAAGTTAACCAAACTGAGCACCGA-3′; primer 3: 5′-CGGTGCCCTGAATGAACTGC-3′; and primer 4: 5′-GATACTTTCTCGGCAGGAGCAA-3′. The caspase 3 PCR reaction conditions were 94°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 40 seconds, 60°C for 75 seconds, and 72°C for 75 seconds. For Bcl-2Tg mice, primer sequences used to determine the presence of the Bcl-2Tg transgene were as follows: primer 1: 5′-TGGATCCAGGATAACGGAGG-3′; primer 2: 5′-TGTTGACTTCACTTGTGGCC-3′. The Bcl-2Tg PCR reaction conditions were 94°C for 1 minute, 54°C for 90 seconds, and 72°C for 90 seconds for 30 cycles.

CBA Immortomouse Cecal Epithelial Cells

Male mice homozygous for a temperature-sensitive SV40 large T antigen (Immortomouse; CBA/Ca × C57Bl/10 hybrid; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA)17 were backcrossed for at least two generations to wild type CBA/J females (Jackson Laboratory) at which point the mice recapitulated susceptibility to amebiasis (culture positive rate >50% on sacrifice 1 week). Progeny were genotyped by PCR for the SV40 transgene by PCR as follows: primer 1: 5′-AGCGCTTGTGTCGCCATTGTATTA-3′; primer 2: 5′-GTCACACCACAGAAGTAAGGTTCC-3′ as previously reported.18 PCR reaction conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 30 cycles at 95°C for 1 minute, 58°C for 2 minutes, and 70°C for 3 minutes. Epithelial cell lines from the cecum were derived from CBA Immortomouse following a protocol of Whitehead and Robinson.12 Briefly the cecum was opened longitudinally, washed in sterile PBS, and decontaminated by soaking in 0.04% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (VWR, West Chester, PA) in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. Tissue was incubated in a solution containing 3 mmol/L EDTA plus 0.5 mmol/L dithiothreitol in PBS for 90 minutes at room temperature, resuspended in PBS, and then crypts and cells were detached by vigorous shaking. Cells were maintained in Ham's F-12 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% of fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mmol/L of glutamine, 5 U/ml of interferon γ, 1 μg/ml of insulin transferring selenium, and 10−5 M of α-thioglycerol at 33°C and were humidified in a 5% CO2 atmosphere (as previously described),17 and cecal epithelial cell patches were seen after ∼2 weeks. Epithelial origin was confirmed by flow cytometry by using cytokeratin-fluorescein isothiocyanate, with cell populations 92.9% positive.

Apoptosis and Inhibition Assays

CBA Immortomouse cecal epithelial cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were grown to confluence in Ham's Complete F-12 medium and co-cultured with E. histolytica HM1:IMSS for 0 to 90 minutes. Apoptosis was assessed for cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments by using the Cell Death Detection enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) plus kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and optical density was normalized to the kit positive control. Phosphatidyl serine staining was assessed by flow cytometry by detaching remaining cells with trypsin (Cellgrow, Herndon, VA) and staining with annexin V per the manufacturer's directions (BD PharMingen, San Jose, CA). Data were collected by using a FACScan cytometer running CellQuest 3.3 software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Data analysis was performed by using FloJo version 8.2 (Treestar, Ashland, OR). For mitochondrial studies cells were incubated with Mitotracker CMXRos (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions; cells were subsequently stained with AnnexinV-APC (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and analyzed by flow cytometry as indicated above.

In Vivo Intracecal Challenge and Histology

For all mouse intracecal inoculations, trophozoites were grown to log phase, counted with a hemacytometer, and 2 × 106 trophozoites in 150 μl were injected thrice intracecally after laparotomy as described.14 At time points indicated mice were sacrificed and ceca were bisected longitudinally. Half of cecal contents were diluted in 500 μl of PBS and tested for E. histolytica antigen by ELISA (E. histolytica II, Techlab, Blacksburg, VA); the remainder was used to inoculate TYI medium, which was cultured for 5 days to determine culture positivity. The other half of the cecum was fixed in Bouin's solution (Sigma, St Louis, MO), paraffin-embedded, and stained by using H&E. Duplicate sections were stained for activated human/mouse caspase 3 by using polyclonal antibody (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Histopathology was scored in blinded fashion for inflammation score, amoeba score, and for numbers of apoptotic cells as previously described.14 For apoptosis quantification we scored circular, crescent-shaped nuclei bubbled up out of the plain of focus and counted at least 200 contiguous luminal epithelial cells as denominator.19 Total millimeters squared of mucosa was measured by using Adobe Photoshop (Seattle, WA).

Statistics

Statistical significance for all proportion data were determined by using the Fisher's exact test. Means or medians were compared by using the t-test or the Mann-Whitney test depending on if data were Gaussian or not, respectively. Data are shown as mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. All P values were two-tailed.

Results

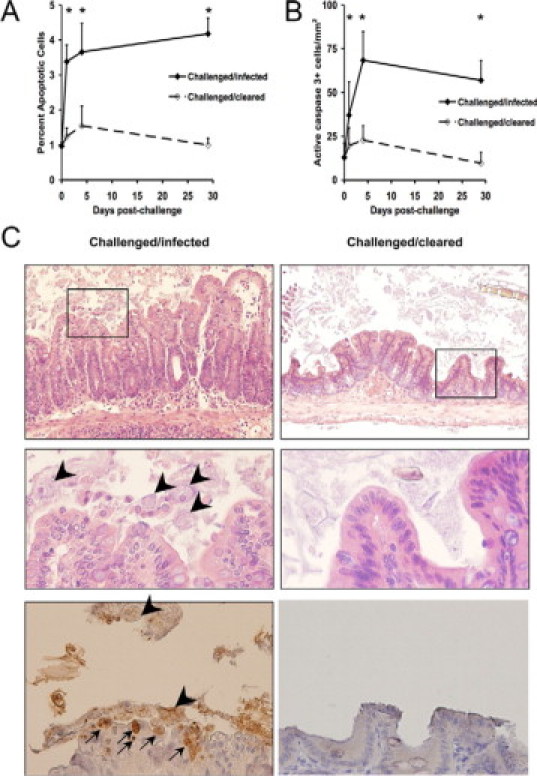

Epithelial Cell Apoptosis Correlates with E. Histolytica Infection

We previously showed that E. histolytica infection of the C3H/HeJ mouse intestine was associated with apoptotic cells at sites of invasion, but the extent of this phenomena and the cell types involved were not documented.20 We have since reported a CBA mouse model of intestinal amebiasis where most mice become patently and persistently infected after intracecal challenge with E. histolytica trophozoites, whereas a minority of animals resist infection in the first few days.21 We compared histological rates of apoptosis in the intestine between these two groups, challenged/infected versus challenged/cleared. By both morphological determination of apoptosis (apoptotic cells appear circular with a crescent-shaped nucleus19,22) and immunohistochemistry for activated caspase 3, we observed abundant apoptosis particularly in the luminal epithelial layer of challenged/infected mice compared with time 0 (naïve mice) and compared with challenged/cleared mice at all subsequent time points (Figure 1, A–C). Increased apoptosis was evident as early as 1 day postchallenge. We, therefore, focused our subsequent experiments on this rapidity of apoptosis and the epithelial cell.

Figure 1.

Epithelial cell apoptosis correlates with E. histolytica infection. CBA mice were infected intracecally with E. histolytica trophozoites and sacrificed at days 1, 4, and 29 as reported previously, whereby successful establishment of infection occurred in >60% of CBA mice at each time point.21 Cecal tissue was fixed and stained with H&E or by immunohistochemistry for activated caspase 3. Apoptosis was scored at the time points indicated by morphological criteria (A: data reported as the percentage of apoptotic cells/total cells) or by activated caspase 3 positive cells (B: data expressed as the total number of apoptotic cells per millimeter squared of epithelial cells). N ≥ 3 mice for each time point. *P < 0.05. C: Representative photomicrographs of challenged/infected versus challenged/cleared cecal tissue at day 29 postchallenge are shown. Top row are H&E stained slides (original magnification, ×100), middle row are insets shown at ×400 (original magnification), and bottom row are caspase 3 stained slides at ×400 (original magnification). Apoptotic cells are apparent within the epithelial layer (arrows) frequently in juxtaposition with amebic trophozoites (arrowheads).

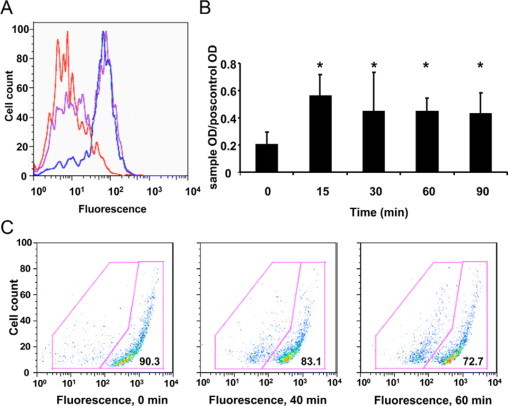

Epithelial Cell Entamoeba Interactions In Vitro

Several investigators have reported that the parasite E. histolytica triggers apoptosis on contact with Jurkat T cells,5,20 human and murine myeloid cells,3,4,10 and hepatocytes.8 By contrast the epithelial cell has received little investigation. Our mouse model of amebiasis results in cecal infection, and therefore we wished to focus our efforts on this particular region of the gut. We first analyzed amoeba: epithelial interactions using primary epithelial cells isolated from the mouse cecum; however, the process of cell isolation triggered such extensive apoptosis as measured by annexin positivity that this system was limited (data not shown). We, therefore, generated a cecal epithelial cell line derived from a CBA mouse by backcrossing the Immortomouse (CBA/Ca × C57Bl/10) to CBA until these mice recapitulated susceptibility to amebic infection (beyond two generations; data not shown) and then generated a conditionally immortalized epithelial cell line from the cecum of these mice as previously described.12 We used these cells in co-culture experiments with amoeba and found that the parasite would directly trigger apoptosis in these cells as measured by annexin positivity and by detection of cytoplasmic histone-associated DNA fragments (Figure 2, A and B). The timing of apoptosis occurred rapidly within minutes after which the parasite would engulf apoptotic cells (data not shown).5,6 We also observed disruption of mitochondrial membrane integrity by mitochondrial vital dye staining, characteristic of activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Figure 2C), a feature that has not previously been described with E. histolytica-mediated apoptosis. Pharmacological inhibition studies were attempted but severely limited by the rapidity and magnitude of apoptosis and engulfment observed during in vitro conditions (data not shown).

Figure 2.

E. histolytica rapidly triggers apoptosis in a cecal epithelial cells in vitro. CBA Immortomouse cecal epithelial cells were grown to confluence and co-incubated with E. histolytica trophozoites. A: AnnexinV binding was assessed at 0 minutes (no amoeba, red line), 30 minutes (purple line), and 60 minutes (blue line). Data are shown from one representative experiment of three. B: Apoptotic DNA fragmentation was determined in cecal epithelial cells by using ELISA as described in Materials and Methods at 0- to 90-minute time points. Results are combined data from two independent experiments. *P < 0.05. C: Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨ) were determined by staining epithelial cells with a mitochondrial vital dye as described in Materials and Methods at 0, 20, and 60 minutes. Disruption of normal mitochondrial function results in decreased accumulation of dye and reduced fluorescence intensity from 90.3% to 72.7%. Data are shown from one representative experiment of two.

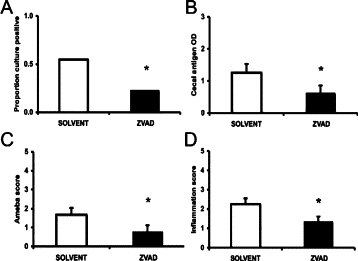

Role of Apoptosis in the Mouse Model

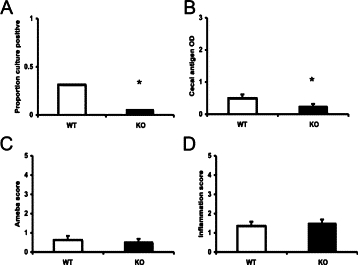

We, therefore, returned to the mouse model and administered the pan-caspase inhibitor ZVAD to CBA mice every other day at doses previously shown to be effective in blocking apoptosis in the amebic liver abscess model (100 μl of a 10 μmol/L solution7). Of note, this dose ZVAD had no direct effect on amebic growth in vitro (data not shown) and the regimen indeed decreased cecal apoptosis scores (1.1 ± 0.4% luminal epithelial apoptotic cells with ZVAD versus 2.5 ± 0.3 with PBS/DMSO, n = 14 and 15, respectively; P = 0.003). Mice were sacrificed at a typical 8 days postchallenge, and we found that all measures of infection were diminished in the ZVAD versus control-treated mice, including culture positive rate, cecal parasite antigen, and histological scores (Figure 3, A–D). We next examined the phenotype of infection in caspase-3-deficient mice because this is a downstream caspase known to be activated in host cells in response to E. histolytica infection.20 These mice were only available on the C57BL/6 background, a mouse strain known to be highly resistant to intestinal amebic infection.14,21 We, therefore, shortened these experiments to 24 hours to try to ascertain whether this molecule was participating in early infection. As expected, these C57BL/6 background mice remained relatively resistant by histological measures; however, the caspase 3 knockout mice did exhibit an even lower rate of amoeba recovery by culture as well as parasite antigen versus their wild type littermates (Figure 4, A–D), suggesting some permissive effect for caspase 3 activity on parasite infection. We then sought to examine the role of apoptosis during established amebic colitis in the CBA model. Mice with established culture-confirmed infection were treated with four doses of ZVAD according to the methods, yet this did not alter infection and inflammation scores (n = 6 ZVAD treated versus n = 5 solvent treated mice, cecal ELISA 0.3 ± 0.2 vs 0.8 ± 0.3, amoeba score 2.4 ± 1.0 vs 2.1 ± 0.5, inflammation score 2.5 ± 0.5 vs 2.5 ± 0.6, respectively; P = not significant for all comparisons). Taken together these experiments were consistent with the concept that apoptosis inhibition can decrease amebic infection rate and severity when administered early but will not necessarily clear established infection under these conditions.

Figure 3.

Caspase inhibition decreases infection in CBA mice challenged with E. histolytica. Male CBA/J mice were injected intraperitoneally with ZVAD (black bars) or PBS/DMSO control (white bars) before and after being challenged intracecally with 2 × 106E. histolytica trophozoites and then sacrificed after 8 days. Cecal contents were assessed for the presence of amoeba by culture (A) and E. histolytica antigen by ELISA (B). Cecal tissue was stained with H&E and scored in blinded fashion for the presence of amoeba (C) and degree of inflammation (D) as detailed in Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three experiments. *P < 0.05, n = 31 and 31 for ZVAD and PBS/DMSO treated mice, respectively.

Figure 4.

Intracecal challenge of caspase-3-deficient mice. Wild type (WT) and caspase-3-deficient C57BL/6 mice were challenged intracecally with 2 × 106E. histolytica trophozoites and sacrificed at 24 hours postchallenge. Cecal contents were assessed for the presence of amoeba by culture (A) and E. histolytica antigen by using ELISA (B). Cecal tissue was stained with H&E and scored in blinded fashion for the presence of amoeba (C) and degree of inflammation (D) as detailed in Materials and Methods. Data are shown as mean ± SE from three experiments. *P < 0.05, n = 38 and 34 for WT and caspase 3 knockout (KO) mice, respectively.

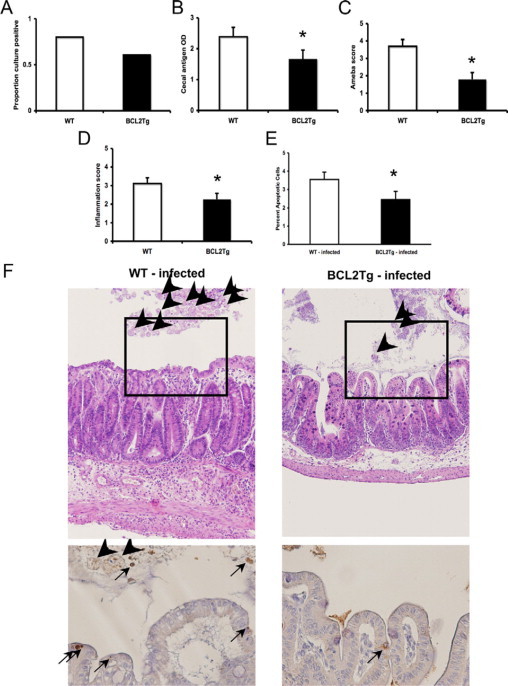

We next wished to ascribe whether apoptosis of the epithelium in particular was playing a role. To do so we used transgenic mice that express the antiapoptotic molecule human Bcl-2 under the expression of an intestinal epithelium specific promoter shown to be particularly active in the mouse cecum (fatty acid binding protein 1), hereafter referred to as Bcl-2Tg mice.15,23 Bcl-2 is a central antiapoptotic regulatory molecule of the outer mitochondrial membrane that can block mitochondrial dysfunction, and therefore we hypothesized that forced Bcl-2 expression would diminish mitochondrial pathways of apoptosis shown to be activated by amoeba in Figure 2C. These Bcl-2Tg mice have been extensively characterized and exhibit diminished intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis when induced by a variety of known stimuli.15,24 The mice were available on the FVB background, a strain that is also relatively susceptible in our model of intestinal amebiasis.25 We sacrificed these mice 5 to 7 days postinoculation, and the experiment showed that forced overexpression of this antiapoptotic regulatory molecule was protective in vivo, as indicated by diminished cecal parasite antigen, amoeba, and inflammation scores (Figure 5, A–D). As expected, rates of apoptosis as measured by histology were diminished in the Bcl-2Tg mice in the setting of the amoebic stimulus (Figure 5, E and F). Of note, rates were not different in Bcl-2Tg mice in the minority of mice that cleared infection or at steady-state naïve mice (data not shown), which is identical to that previously reported with this mouse line.15

Figure 5.

Intracecal challenge of Bcl-2 transgenic mice. Male FVB mice transgenic for epithelial expression of Bcl-2 (Bcl-2Tg) and wild type (WT) littermates were challenged intracecally with 2 × 106E. histolytica trophozoites and sacrificed after 5 to 7 days. Cecal contents were assessed for the presence of amoeba by culture (A) and E. histolytica antigen by ELISA (B). Cecal tissue was stained with H&E and scored in blinded fashion for the presence of amoeba (C) and degree of inflammation (D) as detailed in Materials and Methods. E: Rates of apoptotic cells in the cecum were measured histologically in the infected mice from each group (n = 22 and 15 for WT and Bcl-2Tg mice, respectively). Data are shown as mean ± SE from six experiments. *P < 0.05, n = 28 and 25 for WT and Bcl-2Tg mice, respectively. F: Representative photomicrographs of WT-infected versus Bcl-2Tg-infected cecal tissue at day 5 postchallenge are shown. Top row are H&E stained slides (original magnification, ×100) showing more inflammation, cecal thickness, and amebic trophozoites (arrowheads) in WT mice. Bottom are caspase 3 stained slides at ×400 (original magnification). In WT mice, apoptotic cells are apparent within the epithelial layer (arrows) frequently in juxtaposition with amebic trophozoites (arrowheads).

Discussion

Taken together, these results indicate that during intestinal infection with E. histolytica, epithelial apoptosis occurs, can be triggered directly by the parasite, and promotes the establishment of infection. Our interest in epithelial apoptosis in this model began with our recent finding that apoptosis-related genes were differentially expressed in the epithelial cells of CBA (susceptible to intestinal amebiasis) versus C57BL/6 mice (resistant to intestinal amebiasis).25 We were not wed to a particular hypothesis because we could envision epithelial apoptosis as being either protective or deleterious during intestinal infection. One could imagine apoptosis as protective given the precedent of the certain intestinal helminth models where epithelial apoptosis maintains crypt length and epithelial homeostasis.19 On the other hand, apoptosis could be pathogenic as in the mouse amebic liver abscess model, where hepatocyte apoptosis played a permissive/pathological role in abscess formation.7 Our results were consistent with the latter.

How apoptosis promotes amebic infection is not yet clear, but we can imagine a few possibilities that may be operating in the gut. We know from previous studies that on intracecal inoculation amoeba undergo significant attrition in the first 24 hours.21 In this new and apparently hostile environment, apoptotic cells may constitute an important source of food for amoeba, as it has been clearly shown that they preferentially phagocyte apoptotic corpses in culture.5 Another possibility is that epithelial apoptosis, insofar as it promotes epithelial barrier dysfunction,26 allows amoeba access to tissue or serum constituents that promote survival of the trophozoite. Examples could include C1q and collectins, which promote parasite phagocytosis,27 or tumor necrosis factor, which has been reported to be chemoattractant for E. histolytica.28 Finally, it is possible that apoptosis enables infection by limiting necrosis and its resultant inflammatory response, which could otherwise be protective, since we know from this model that Th1 responses and neutrophils limit infection.21,29 Finally, because our mouse model of amebiasis is one of disease not asymptomatic colonization, the role of epithelial apoptosis during pure E. histolytica carriage remains unclear.

Although we clearly found that apoptosis of epithelial cells is directly triggered by the parasite in vitro, we acknowledge that the apoptosis observed histologically in the model could be because of either this direct parasite contact or result secondarily from the intestinal inflammation (eg, akin to the increased apoptosis observed in ulcerative colitis30). We speculate that both aspects contribute, but particularly the former because histologically we observed the highest rates of apoptosis in the vicinity of amoeba (Figure 1). The mechanism of epithelial cell apoptosis on amoeba contact is peculiarly rapid as has been appreciated with the Jurkat T cell.5 The mechanism is difficult to examine in vitro; however, we clearly observed mitochondrial membrane dysfunction in response to amoeba, a marker of activation of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Earlier work using a myeloid cell line and different experimental conditions reported that Bcl-2 overexpression could not diminish E. histolytica mediated killing in vitro,3 suggesting that the intrinsic apoptotic pathway was not a dominant feature in those experiments. In this work, however, we could ascribe a role for Bcl-2 in vivo in that epithelium-specific Bcl-2 overexpressing mice exhibited diminished infection scores. The discrepancy could be because of different apoptotic programs in the cell types (epithelial versus myeloid) or the differences in the experimental systems used. In previous work with these Bcl-2Tg mice, it was shown that the Bcl-2 overexpression in the intestinal epithelium had no effect on steady-state epithelial apoptosis/homeostasis but did mitigate cell death in the setting of apoptotic stimuli such as γ-irradiation, mesenteric ischemia-reperfusion, cecal ligation and puncture, pneumonia, acute lung injury, and sepsis.15,24,31,32 In this context, amebic colitis is an additional stimulus that promotes epithelial apoptosis that can be partly rescued with Bcl-2 overexpression. Again, whether it is the amoeba-mediated or inflammation-mediated epithelial apoptosis (or both) that are Bcl-2 inhibitable in this model is unsettled, but regardless Bcl-2 can stand as a possible target for preventing or diminishing intestinal amebiasis.

The mechanisms used by the parasite to elicit apoptosis remain an active area of investigation in several cell types, and we would put forward that the epithelial cell needs further study. This parasite lives in the gut with constant contact with the epithelium, and how the parasite has developed this capacity to trigger a homeostatic host cell function speaks to its evolutionary success. Understanding the parasite molecules participating in this process should shed light on novel virulence factors for this important infection.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Virginia Research Histology Core of the Center for Research in Reproduction. We thank Sheila Crowe and William A. Petri, Jr. for helpful advice, Craig M. Coopersmith and Richard Hotchkiss for mice, and David Lyerly (Techlab) for the E. histolytica II ELISA kits.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants AI071373 and DK058404, a Basic Career Award from Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America, a Pilot and Feasibility Award from the University of Virginia Silvio O. Conte Digestive Disease Research Center, and the Molecular Biology/Gene Expression Core of the University of Virginia NIH/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Digestive Diseases Research Core Center (DK067629).

No conflicts of interest exist for any author. Sponsors played no role in the study design, data analysis, writing, or decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Haque R, Huston CD, Hughes M, Houpt E, Petri WA., Jr Amebiasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1565–1573. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prathap K, Gilman R. The histopathology of acute intestinal amebiasis: a rectal biopsy study. Am J Pathol. 1970;60:229–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ragland BD, Ashley LS, Vaux DL, Petri WA., Jr Entamoeba histolytica: target cells killed by trophozoites undergo DNA fragmentation which is not blocked by Bcl-2. Exp Parasitol. 1994;79:460–467. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sim S, Yong TS, Park SJ, Im KI, Kong Y, Ryu JS, Min DY, Shin MH. NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species-mediated activation of ERK1/2 is required for apoptosis of human neutrophils induced by Entamoeba histolytica. J Immunol. 2005;174:4279–4288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huston CD, Boettner DR, Miller-Sims V, Petri WA., Jr Apoptotic killing and phagocytosis of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Immun. 2003;71:964–972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.2.964-972.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boettner DR, Huston CD, Sullivan JA, Petri WA., Jr Entamoeba histolytica and Entamoeba dispar utilize externalized phosphatidylserine for recognition and phagocytosis of erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3422–3430. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3422-3430.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan L, Stanley SL., Jr Blockade of caspases inhibits amebic liver abscess formation in a mouse model of disease. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7911–7914. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7911-7914.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seydel KB, Stanley SL., Jr Entamoeba histolytica induces host cell death in amebic liver abscess by a non-Fas-dependent, non-tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent pathway of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2980–2983. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2980-2983.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim KA, Lee YA, Shin MH. Calpain-dependent calpastatin cleavage regulates caspase-3 activation during apoptosis of Jurkat T cells induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1209–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berninghausen O, Leippe M. Necrosis versus apoptosis as the mechanism of target cell death induced by Entamoeba histolytica. Infec Immun. 1997;65:3615–3621. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3615-3621.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsutsumi V, Shibayama M. Experimental amebiasis: a selected review of some in vivo models. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitehead RH, Robinson PS. Establishment of conditionally immortalized epithelial cell lines from the intestinal tissue of adult normal and transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G455–G460. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90381.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamano S, Asgharpour A, Stroup SE, Wynn TA, Leiter EH, Houpt E. Resistance of C57BL/6 mice to amoebiasis is mediated by nonhemopoietic cells but requires hemopoietic IL-10 production. J Immunol. 2006;177:1208–1213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houpt ER, Glembocki DJ, Obrig TG, Moskaluk CA, Lockhart LA, Wright RL, Seaner RM, Keepers TR, Wilkins TD, Petri WA., Jr The mouse model of amebic colitis reveals mouse strain susceptibility to infection and exacerbation of disease by CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4496–4503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coopersmith CM, O'Donnell D, Gordon JI. Bcl-2 inhibits ischemia-reperfusion-induced apoptosis in the intestinal epithelium of transgenic mice. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G677–G686. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuida K, Zheng TS, Na S, Kuan C, Yang D, Karasuyama H, Rakic P, Flavell RA. Decreased apoptosis in the brain and premature lethality in CPP32-deficient mice. Nature. 1996;384:368–372. doi: 10.1038/384368a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jat PS, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Tanaka Y, Yannoutsos N, Larsen L, Kioussis D. Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5096–5100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takacs-Jarrett M, Sweeney WE, Avner ED, Cotton CU. Generation and phenotype of cell lines derived from CF and non-CF mice that carry the H-2K(b)-tsA58 transgene. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C228–C236. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.1.C228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cliffe LJ, Potten CS, Booth CE, Grencis RK. An increase in epithelial cell apoptosis is associated with chronic intestinal nematode infection. Infect Immun. 2007;75:1556–1564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01375-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huston CD, Houpt ER, Mann BJ, Hahn CS, Petri WA., Jr Caspase 3-dependent killing of host cells by the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:617–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asgharpour A, Gilchrist C, Baba D, Hamano S, Houpt E. Resistance to intestinal Entamoeba histolytica infection is conferred by innate immunity and Gr-1+ cells. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4522–4529. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4522-4529.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potten CS, Wilson JW, Booth C. Regulation and significance of apoptosis in the stem cells of the gastrointestinal epithelium. Stem Cells. 1997;15:82–93. doi: 10.1002/stem.150082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sweetser DA, Birkenmeier EH, Hoppe PC, McKeel DW, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying generation of gradients in gene expression within the intestine: an analysis using transgenic mice containing fatty acid binding protein-human growth hormone fusion genes. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1318–1332. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.10.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coopersmith CM, Stromberg PE, Dunne WM, Davis CG, Amiot DM, 2nd, Buchman TG, Karl IE, Hotchkiss RS. Inhibition of intestinal epithelial apoptosis and survival in a murine model of pneumonia-induced sepsis. JAMA. 2002;287:1716–1721. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.13.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamano S, Becker S, Asgharpour A, Ocasio YP, Stroup SE, McDuffie M, Houpt E. Gender and genetic control of resistance to intestinal amebiasis in inbred mice. Genes Immun. 2008;9:452–461. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulzke JD, Bojarski C, Zeissig S, Heller F, Gitter AH, Fromm M. Disrupted barrier function through epithelial cell apoptosis. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1072:288–299. doi: 10.1196/annals.1326.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teixeira JE, Heron BT, Huston CD. C1q- and collectin-dependent phagocytosis of apoptotic host cells by the intestinal protozoan Entamoeba histolytica. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1062–1070. doi: 10.1086/591628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blazquez S, Zimmer C, Guigon G, Olivo-Marin JC, Guillen N, Labruyere E. Human tumor necrosis factor is a chemoattractant for the parasite Entamoeba histolytica. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1407–1411. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1407-1411.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo X, Stroup SE, Houpt ER. Persistence of Entamoeba histolytica infection in CBA mice owes to intestinal IL-4 production and inhibition of protective IFN-gamma. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:139–146. doi: 10.1038/mi.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hagiwara C, Tanaka M, Kudo H. Increase in colorectal epithelial apoptotic cells in patients with ulcerative colitis ultimately requiring surgery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:758–764. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Husain KD, Stromberg PE, Javadi P, Buchman TG, Karl IE, Hotchkiss RS, Coopersmith CM. Bcl-2 inhibits gut epithelial apoptosis induced by acute lung injury in mice but has no effect on survival. Shock. 2003;20:437–443. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000094559.76615.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coopersmith CM, Chang KC, Swanson PE, Tinsley KW, Stromberg PE, Buchman TG, Karl IE, Hotchkiss RS. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in the intestinal epithelium improves survival in septic mice. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:195–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]