Abstract

Transgenic mice expressing human mutated superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) linked to familial forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis are frequently used as a disease model. We used the SOD1G93A mouse in a cross-breeding strategy to study the function of physiological prion protein (Prp). SOD1G93APrp−/− mice exhibited a significantly reduced life span, and an earlier onset and accelerated progression of disease, as compared with SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice. Additionally, during disease progression, SOD1G93APrp−/− mice showed impaired rotarod performance, lower body weight, and reduced muscle strength. Histologically, SOD1G93APrp−/− mice showed reduced numbers of spinal cord motor neurons and extended areas occupied by large vacuoles early in the course of the disease. Analysis of spinal cord homogenates revealed no differences in SOD1 activity. Using an unbiased proteomic approach, a marked reduction of glial fibrillary acidic protein and enhanced levels of collapsing response mediator protein 2 and creatine kinase were detected in SOD1G93APrp−/− versus SOD1G93A mice. In the course of disease, Bcl-2 decreases, nuclear factor-κB increases, and Akt is activated, but these changes were largely unaffected by Prp expression. Exclusively in double-transgenic mice, we detected a significant increase in extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 activation at clinical onset. We propose that Prp has a beneficial role in the SOD1G93A amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mouse model by influencing neuronal and/or glial factors involved in antioxidative defense, rather than anti-apoptotic signaling.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is characterized by rapid degeneration of motor neurons in the spinal cord, brain stem, and cortical Betz cells. As a result, focal muscle wasting, weakness, and spasticity develop focally. These symptoms ultimately lead to global paralysis. Patients usually die due to respiratory failure within 3 years of symptom onset.1

The causes of ALS are diverse; 10 to 15% of cases are familial with autosomal dominant inheritance, and 20% of these are related to point mutations in the gene encoding Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). SOD1 is a ubiquitously expressed homodimeric protein that catalyzes the reaction of O2− to O2 and H2O2, which is then further metabolized by glutathione peroxidase. Mice overexpressing human mutated SOD1 (muSOD1) linked to ALS, develop disease resembling ALS in humans by a toxic gain of function.2 Several properties of muSOD1 were proposed to contribute to toxic gain of function, including enhanced peroxidase activity and formation of peroxynitrite, changes in copper and zinc binding, and aggregation of the enzyme. ALS progression is accompanied by oxidative stress processes, glutamate-induced excitotoxicity, cytoskeletal abnormalities, inflammatory processes, and toxicity via extracellular muSOD1.2,3 The apoptotic cascade is activated in the ALS model, shown by sequential activation of caspase-1 and −3.4 Interestingly, Bcl-2 overexpression had a neuroprotective effect and, like intrathecal administration of caspase inhibitors, led to a slowed disease progression and increased life span in these mice.5,6 More recently, it was proposed that not only neurons themselves contribute to the neurodegenerative process in ALS but also non-neuronal cells, particularly microglia and astrocytes.7–10 Expression of muSOD1 in non-neuronal cells was sufficient to induce cell death in nearby motor neurons lacking muSOD1.11,12

Since an early decrease of prion protein (Prp) mRNA has been described in an ALS model,13 loss of Prp function might contribute to the neurodegenerative process not only in prion diseases but also in ALS. A number of physiological functions have meanwhile been attributed to Prp, including antioxidative and anti-apoptotic properties and involvement in transmembrane signaling and cell adhesion.14 Additionally, as recently reported in cell culture models, Prp regulates astrocytic signaling15,16 and thereby might also influence neuron−glia signaling relevant for ALS pathogenesis. Clarifying the role of Prp in models of neurodegeneration is of special interest, since Prp as membrane protein might become an easily accessible drug target for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases as a spin-off of the current search for antiprion drugs.17

In the present study, we analyzed the function of physiological Prp in a mouse model of ALS by cross-breeding mice transgenic for human SOD1 with G93A mutation (SOD1G93A) with Prp knockout (Prp−/−) mice. Characterization of the SOD1G93APrp−/− mice concerning motoric properties, disease progression, and life span, paralleled by histopathological, immunochemical, and proteomic analyses, revealed that Prp has a protective role potentially by influencing mechanisms assuring neuronal survival.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Breeding and Genotyping

The use and care of the mice was performed in accordance with the national guidelines and was approved by local authorities. Male mice transgenic for human SOD1G93A (huSOD1G93A, B6.Cg-Tg[SOD1-G93A]1Gur/J; stock number 004435) were acquired from the Jackson laboratory (Ben Harbor, Maine).

The principle cross-breeding strategy included two steps: SOD1G93A male mice were crossed with female Prp deletion mutant mice, designated herein as Prp−/−, in a first breeding step. Offspring were analyzed for presence of the SOD1G93A transgene in accordance with Jackson Laboratory protocol using the SOD1 primers 5′-CATCAGCCCTAATCCATCTGA-3′, and 5′-CGCGACTAACAATCAAAGTGA-3′. Interleukin-2 served as housekeeping gene (5′-CTAGGCCACAGAATTGAAAGATCT-3′ and 5′-GTAGGTGGAAATTCTAGCATCATCC-3′). To obtain animals of the four possible genotypes, in a second breeding step, female mice without the SOD1 transgene were crossed with SOD1G93A transgenic males, both from the F1 generation and heterozygous with regard to Prp. Resulting F2 mice were again genotyped with respect to SOD1G93A transgene. Genotype of the Prp locus was obtained by two PCRs specific for either wild-type Prp (forward primer 5′-CAGACTATCAAGCTTCATGGCGAACCTTGGCT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GCAGGAAGGTCTAGATCATCCCACGATCAGGA-3′) or the neomycin resistance cassette.18 The genetic background of animals cross-bred and analyzed in the present study is a mixture of C57Bl/6J and 129/SV (ev) from Prp-deficient mice and C57Bl/6J from SOD1 transgenic mice.

Two populations of double transgenic mice and respective controls were independently bred for the analyses reported here. For the first group of animals, SOD1G93A mice obtained from Jackson Lab were crossbred with C57/Bl6 mice for three generations to get enough animals for the F1 cross-breeding step. SOD1G93A transgenic mice resulting from this cross-breeding displayed disease onset at approximately 130 days and were terminally ill at about 160 days. These mice were analyzed for rotarod performance, muscle strength, body weight, disease progression (disease onset, paralysis), and survival. Tissues of both male and female mice were subjected to SOD1 activity assay, motor number determination, immunohistochemistry, immunoblots, and two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2D-DIGE) analyses.

A second group of animals was crossed applying an identical cross-breeding strategy, but, in contrast to the first group, a second group of commercially obtained SOD1 transgenic mice was used to generate the F1 (without interposed cross-breeding with C57/Bl6). Mice resulting from this breeding showed earlier disease onset at an age of about 105 days and shorter life spans of around 130 days. Despite the different SOD1 transgene content of the two cross-breeding groups and by that different disease progression, we observed earlier disease onset and shorter survival times in the SOD1 transgenic mice devoid of Prp, as compared with wild-type-Prp in cross-breeding group 2 (data not shown), as described in detail for cross-breeding group 1 in the Results above. The second-group mice were analyzed for motor neuron numbers and characterized by immunohistochemistry, and immunoblots.

According to Jackson lab, SOD1G93A transgenic mice have a life span between 130 and 160 days, therefore the survival times observed in the two analyzed mouse populations fit well to the Jackson description. Nevertheless, to ensure equal amounts of huSOD1G93A transgene in Prp+/+ and Prp−/− mice, we determined the DNA content of the SOD1G93A transgene by real time PCR as described previously19 for both mouse groups that were generated and analyzed here.

Disease Stages and Life Span

Clinical investigations of mice were done in accordance with the consensus statement.20 Mice were observed daily for specific motor symptoms. Two visible stages, i) first signs of gait impairment characterized by groggy movements and abnormal swinging and shaking of the hind limbs, and ii) first signs of paresis, were scored for each mouse. In addition, measurable parameters indicative of earliest disease stages (peak of body weight curve) and beginning of late disease (10% body weight loss) according to Boillee et al21 were evaluated. The loss of the righting reflex was defined as the end stage of the disease.

Body Weight and Motor Performance

Male mice were weighed and analyzed for their muscle strength by grip test (Bioseb, France)22 when they were 70 days old and measurements were repeated weekly until the end of the experiment. The grip strength test was repeated three times for each animal with a constant velocity, and mean strength was calculated.

To assess motor coordination and strength, a rotarod apparatus (Rotarod Version 1.2.0. MED Associates Inc., Vermont) was used. Weekly, three trials with an accelerating speed from 4 rpm to 40 rpm were performed and the best result was recorded, with 300 seconds being the arbitrary cut-off-time.22

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

At the time of showing first clinical symptoms and at terminal stage, three to five mice of each genotype group were assigned for histopathological quantification of spinal cord motor neurons. Mice were anesthetized with 500 mg/kg thiopental i.p. and perfused transcardially with 0.9% NaCl solution followed by 4% paraformaldehyde. The spine was removed and post-fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% paraformaldehyde. Cervical, thoracic, and lumbar segments of the spinal cord were paraffin-embedded, and transverse sections were cut for motor neuron count. For each segment, a total of seven 7-μm sections were cut at 49-μm intervals, deparaffinized, and stained with H&E. Alternatively, the spinal cords were prepared from NaCl-perfused mice, separated in cervical, thoracic, and lumbar segments, and cryo-conserved. For motor neuron count, 12-μm cryosections, cut at 84 μm intervals, were fixed with acetone and subsequently H&E-stained.

From the ventral horn area of each section, images were captured at ×10 magnification (BX51, Olympus, Hamburg, Germany) and counted by a person who was blind with regard to age and genotype of the mice. Only large motor neurons with clearly identifiable nucleus and nucleolus were counted.

For glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry, spinal cord sections were deparaffinized by xylol and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was achieved by treatment with 0.02 mg/ml proteinase K for 10 minutes at 37°C. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by 3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 minutes. After the slices were blocked with goat serum (1:20 in PBS), polyclonal anti-GFAP-antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1:800 was applied overnight at 4°C. After three washes, tissue was incubated with secondary antibody (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) for 1 hour at room temperature. After removal of excess antibodies, bound peroxidase was detected applying 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma-Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany) as precipitating substrate. At the end, slices were counterstained with hematoxylin.

SOD Assay

Whole spinal cord was prepared from NaCl-perfused mice, homogenized by sonication in PBS containing 0.2 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 μg/ml aprotinin. Protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma, Munich, Germany). The SOD activity assay is based on water soluble tetrazolium reduction by superoxide anion (produced from xanthine by xanthine oxidase) to a colored water soluble tetrazolium formazan product and was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor). Total SOD activity was determined as well as Cu/ZnSOD activity in the presence of MnSOD inhibitor ethanol/chloroform and MnSOD activity while inhibiting Cu/ZnSOD by 2 mmol/L CN−. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that inhibits the assay reaction rate by 50%.

Immunoblots

Tissue homogenates were prepared in PBS containing protease inhibitor cocktail (complete mini, Roche, Mannheim, Germany), 1 mmol/L pyrophosphate, 1 mmol/L ortho-vanadate, 5 mmol/L NaF, by ultrathorax and sonication. Protein concentration in 2000 rpm (10 minutes 4°C) supernatants was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Sigma, Munich, Germany). Then, 20 to 40 μg of protein were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblots were performed as described elsewhere.23 Membranes were analyzed using a CCD camera (LAS-1000; Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and bands were densitometrically quantified using Quantity One software (BioRad, Munich, Germany).

Primary antibodies against Akt, phosphoAkt, ERK1/2, phosphoERK1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers), GFAP (H50, Santa Cruz biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), Bcl-2 (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), and nuclear factor (NF)-κB subunit p65 (Santa Cruz) were diluted 1:1000 (anti-NF-κB 1:750, anti-Bcl-2 1:500) in blocking solution. For control of equal protein amounts loaded to the gel we decided to perform β-tubulin blots (anti-β tubulin, 1:25000, Sigma, Munich, Germany), since actin expression levels were shown to be influenced in ALS.24 For normalization, tubulin bands detected on stripped membranes (2% SDS, 0.0625 mol/L Tris-HCl pH6.7, 0.7% β-mercaptoethanol, 30 minutes, 60°C) were quantified.

Proteomic Analysis by 2D-DIGE

Sample preparation, dye labeling, gel electrophoresis, and data analysis was done according to recently published protocols.18,25 Briefly, whole spinal cord homogenates were produced by sonication in PBS containing protease inhibitor mix (complete mini, Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and lysed in 7 mol/L urea, 2 mol/L thiourea, 4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonate, and 30 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.1) for subsequent labeling with CyDyes (GE Health Care). Isoelectric focusing was performed in an immobilized pH gradient (24-cm Immobiline dry strips [pH 3 to 10] non linear; GE) for ∼56 kVh. SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed in homogeneous 12% polyacrylamide gels. Three biological replicates of spinal cord proteins of mice of the SOD1G93A and the SOD1G93APrp−/− group were analyzed with DeCyder differential analysis software (GE). For subsequent mass spectrometric protein identification, the gels were post-stained with colloidal Coomassie. Manually excised gel plugs were subjected to an automated platform for the identification of gel-separated proteins.26 Briefly, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time of flight mass spectrometry was used for peptide mass fingerprinting and sequencing. Data were searched in the Swiss-Prot primary sequence database using Mascot 2.1. The minimal requirement for accepting a protein as identified was at least one peptide sequence match above identity threshold in coincidence with at least 20% sequence coverage in peptide mass fingerprinting. For details see Brechlin et al25 and references therein.

Calculations and Statistics

Measures were analyzed for statistical differences with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney test. Correlation was calculated with the Spearman correlation test. Survival was examined by Kaplan-Meier log rank. SigmaStat software (asknet AG, Karlsruhe, Germany) was used for these calculations. P values below P = 0.05 were regarded as significant and below P = 0.001 as highly significant. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

Breeding and SOD1G93A Transgene DNA Content

In mice of the four genotypes analyzed in the present study, the SOD1G93A transgene as well as prion gene was inherited in an almost Mendelian fashion. The distribution of genotypes is shown in supplemental Table S1 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org. The relative content of transgenic DNA encoding for SOD1G93A was nearly twice as high in the second animal group analyzed, representing F2 offspring of SOD1G93A males obtained from Jackson labs, compared with the DNA content determined for animals of the first group analyzed that were cross-bred from SOD1 transgenic animals after three additional cross-breeding steps with C57/Bl6 female mice (Prp+/+ and Prp−/− males: first mouse group analyzed 87.2 ± 20.2 [n = 13 males] and 97.2 ± 19.7 [n = 11 males]; second mouse group analyzed 168.8 ± 28.6 [n = 13 males] and 178.9 ± 35.2 [n = 5 males]). Higher transgene content was paralleled by an accelerated disease progression, but was independent of the Prp genotype, which was a prerequisite for this study (see detailed results in Supplemental Figure S1 in the supplemental material section at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

Accelerated Disease Progression and Enhanced Vacuolization in SOD1G93APrp−/− Mice

Depending on Prp expression, disease onset, disease progression and survival times of the ALS model mice differed (Figure 1). SOD1G93APrp−/− mice had shorter survival times (154.9 ± 9.1 day, n = 22) than SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice (170.4 ± 17.6 days, n = 24) (P < 0.001). The life span decrease due to Prp knockout was more pronounced in male mice, but significant both in male (151.9 ± 10.9 vs. 171 ± 16.6 days, Figure 1A) and in female mice (157.9 ± 6.0 vs. 168.4 ± 21.5, Figure 1B).

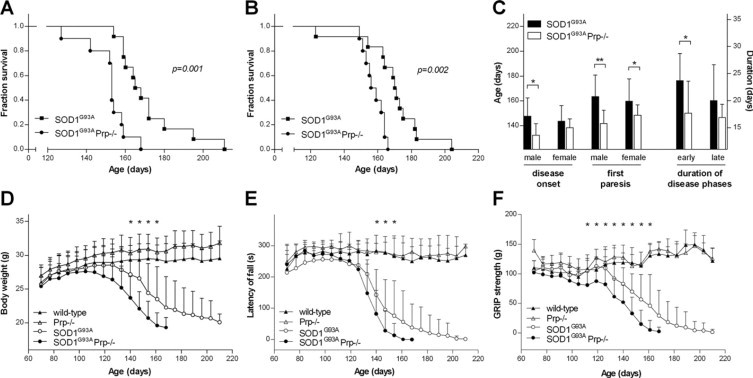

Figure 1.

Diagrams showing data on disease onset, progression, and survival of SOD1G93A transgenic mice (n = 12 males and females, respectively) and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice (n = 10 males, n = 12 females). Kaplan Meier survival curves of male (A) and female (B) SOD1G93A transgenic mice dependent on Prp expression. The log rank P values are shown. C: On the left, the diagram shows Prp dependent age of SOD1G93A male and female mice when developing first clinical disease signs (gait impairment) and when developing first pareses. On the right, the difference in the duration of early disease phase (ie, from peak of body weight curve until the time when mice lost 10% body weight) and of the late disease phase (ie, 10% body weight loss until terminal disease stage) is illustrated. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Analyses by Mann-Whitney test revealed significant differences in age at disease onset in males (P = 0.007), onset of pareses in males (P < 0.001) and females (P = 0.019), and duration of early disease phase (P = 0.024). Body weight (D), rotarod performance (E), and GRIP strength (F) of the control mouse groups (wild-type and Prp−/−), and of Prp expressing and Prp deficient SOD1G93A transgenic mice. The difference in body weight of SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/− group was significant from day 140 (P = 0.018) until end of experiment, as indicated by asterisks (d147 P = 0.005, d154 P = 0.034, d161 P = 0.022). GRIP strength and rotarod performance were determined tree-times for each tested animal per week. Plotted are mean ± standard deviations. Significant differences in the SOD1G93A and the SOD1G93APrp−/− group are indicated by asterisks.

First symptoms, defined as first signs of gait impairment, were seen in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice at day 135.4 ± 8.6 (n = 20), which was significantly earlier (P = 0.004) than observed for the SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice (day 145.0 ± 13.5, n = 24). Also late disease stage, defined as onset of paresis, started earlier (P < 0.001) in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice (day 145.2.4 ± 9.9, n = 20) compared with SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice (day 161.6 ± 17.3, n = 24) (Figure 1C, left panel). Also, when comparing disease onset and progression according to Boillee et al21 SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/− groups differed. Accelerated disease progression in the SOD1G93APrp−/− group was mainly observed in the early phase of disease (P = 0.024)(Figure 1C, right panel). Calculating Kaplan-Meier log rank, the difference in disease onset just failed to be significant (P = 0.051), whereas the difference in onset of late disease was significant (P = 0.003)(see Supplemental Figure S2 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org).

The body weight of both SOD1 wild-type and of SOD1G93A transgenic animals was dependent on the Prp genotype (Figure 1D). SOD1 wild-type mice weighed less when they were Prp+/+ during the entire course of the experiment. SOD1G93APrp−/− mice started to lose weight when they were 117.3 ± 11.7 days old, whereas peak of weight curve of SOD1G93APrp+/+ group was about 10 days later (day 127.9 ± 13.7). Difference in body weight was significant from day 140 (P = 0.018) until end of experiments.

Testing of the motor abilities of the mice was performed by rotarod, starting from day 70, and measurements were performed weekly until day 210 of age (Figure 1D). In the first 3 weeks, a training effect can be seen in all groups, followed by a plateau phase between days 91 and 105. In this period, SOD1G93A mice showed a slightly impaired performance. Then, at day 112 of age, the running time of SOD1G93APrp−/− began to decrease, while SOD1G93A mice had a stable performance until day 119. At an age of 161 days, none of the SOD1G93APrp−/− mice was able to balance and run on the rotarod, whereas this stage was not reached in the SOD1G93A group before day 203. When comparing the two SOD1G93A groups, we found statistically significant differences at the age of 147, 154, and 161 days (P = 0.015, P = 0.005, and P = 0.006, respectively), pointing to the faster disease progression in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice compared with SOD1G93A mice. Motor properties of the two SOD1 wild-type groups were comparable during the experimental course (Figure 1E).

Wild-type SOD1 groups showed similar muscle strength. SOD1G93APrp−/− mice lost muscle strength earlier than SOD1G93A mice. The difference is significant from day 105 (P = 0.016) until end of experiment (Figure 1F).

Parallel to the development of symptoms, the typical histopathological changes—degenerating motor neurons and vacuolization—can be observed in spinal cord slices of ALS model mice (Figure 2A). Decreased counts of motor neurons determined in the SOD1G93APrp−/− group at disease onset and final stage (Figure 2C) reflected the outcome in the GRIP and rotarod tests, as well as the disease stage scores. At days 40 and 80, no motor neuron degeneration was observed (data not shown). At clinical onset, we found significantly fewer motor neurons in lumbar, thoracic and cervical spinal cord of SOD1G93APrp−/− mice, as compared with those expressing Prp. At final disease stage, the differences were less pronounced in the lumbar region and not significant in the cervical region, but still highly significant in the thoracic spinal cord region (Figure 2C).

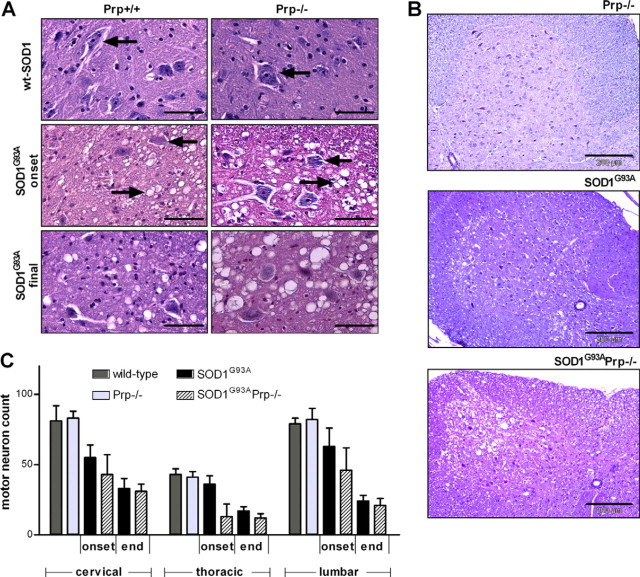

Figure 2.

Representative spinal cord slices and motor neuron counts from wild-type, Prp−/−, SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice. A: The upper panel shows tissue from mice expressing wild-type SOD1. Arrows depict healthy motor neurons. In SOD1G93A transgenic mice at disease onset (middle panel) and at final disease stage (lower panel), the typical degeneration of motor neurons (arrows from the right) and vacuolization (arrows from the left) can be seen. Pictures were taken from H&E-stained 7-μm sections of formalin-fixed tissue scale bars = 50 μm. B: Overviews of cervical spinal cord regions of male mice at time of disease onset. In the Prp−/− tissue (top) no vacuolization can be seen, as is the case in SOD1G93A anterior horn (middle) and, to a greater extent, in SOD1G93APrp−/− tissue (bottom). Scale bars = 200 μm. C: Number of healthy motor neurons counted in lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spinal cord regions of mice at disease onset (SOD1G93An = 3, SOD1G93APrp−/− n = 2) for each genotype), of mice at final disease stage (SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/−, n = 3, respectively) and of respective controls (wild-type and Prp−/− n = 3, respectively). Seven sections 49 μm apart (or in case of cryo-conserved tissue, 84 μm apart) were evaluated for each animal and region and the mean was calculated. In the diagram mean values ± standard deviations of the individual mice of a certain genotype are given. The differences between SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp are significant (P > 0.05) with exception of the cervical region at final disease stage. P values for disease onset were P = 0.0067 (lumbar), P = 0.0039 (thoracic) and P = 0.0023 (cervical) and for terminal disease stage P = 0.0272 (lumbar) and P = 0.0002 (thoracic). No differences in motor neuron numbers were detected comparing wild-type with Prp−/−.

Accompanying the decreased number of motor neurons at disease onset, a massive increase in the number and dimension of large vacuoles could be observed in anterior horn of spinal cord of SOD1G93APrp−/− (Figure 2B, bottom) compared with mice expressing Prp (Figure 2B, center). No vacuoles were observed in SOD1 wild-type spinal cord, either in animals expressing Prp (data not shown) or in Prp knockouts (Figure 2B, top).

Prp Deficiency Does Not Influence SOD Activity

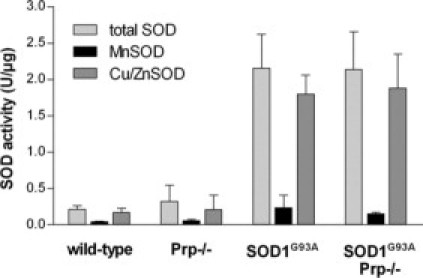

Activities of Cu/ZnSODs and MnSOD were determined in spinal cord lysates of final disease stage SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/− male mice and of wild-type and Prp−/− mice (Figure 3). In line with previous reports, the Cu/ZnSOD activity was increased in animals overexpressing SOD1G93A.27 MnSOD activity was also slightly increased, probably due to the technical artifact of an insufficient inhibition of Cu/ZnSOD by potassium cyanide. Neither total SOD activity, nor that of Cu/ZnSOD or MnSOD was influenced by Prp knockout.

Figure 3.

SOD activities determined in lysates of spinal cord homogenates of male mice at final disease stage. Animals with the genotypes Prp+/+ (n = 2), Prp−/− (n = 2), SOD1G93A (n = 4) and SOD1G93APrp−/− (n = 4) are compared. The activities of total SOD, of MnSOD in the presence of cyanide to block Cu/ZnSOD, and of Cu/ZnSOD in the presence of ethanol/chloroform to block MnSOD, are shown.

GFAP Expression Is Reduced in SOD1G93APrp−/− Mice

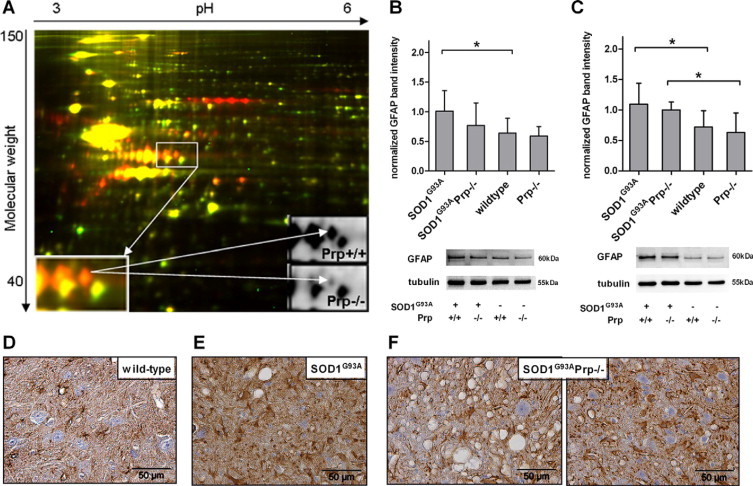

Differential proteome analysis of ALS mice by 2D-DIGE revealed significant differences secondary to the loss of Prp. When the final stage spinal cord homogenates of male Prp+/+ and Prp−/− SOD1G93A transgenic mice were compared, several protein spots of altered abundance were detected (Figure 4A). By mass spectrometry, three spots were identified as GFAP, which was identified to be down-regulated in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice by 50%, 60%, and 70%, respectively. In contrast, dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 (DPYSL2), and creatine kinase (brain type) were up-regulated in these mice (for DIGE and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization results see Supplemental Table S2 and Supplemental Figure S3 at http://ajp.amjpathol.org). We validated the result of the DIGE analysis on GFAP down-regulation in end-symptomatic female mice and additionally in male mice at disease onset by immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting. In spinal cord homogenates at the beginning of the clinical phase (Figure 4B) and terminal disease stage (Figure 4C), GFAP expression levels were increased in SOD1G93A transgenic compared with SOD1 wild-type mice (onset n = 7 versus n = 7 males, P = 0.0487; final stage n = 6 versus n = 10 females, P = 0.0329). There is a trend toward reduced GFAP in SOD1G93APrp−/− versus SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice late in disease and, more pronounced, at disease onset. Terminally, GFAP was significantly increased in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice compared with Prp knockouts without the SOD1 transgene (n = 6 versus n = 4 females, P = 0.0033). A similar difference could not be observed at disease onset (n = 7 versus n = 4 males, P = 0.1152) because of the trend toward reduced GFAP levels in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice. SOD1G93A mice with and without Prp did not differ in their GFAP expression levels.

Figure 4.

A: 2D-DIGE analysis of whole brain homogenates of two individual SOD1G93A male mice either expressing Prp (Prp+/+, red) or Prp knockout (Prp−/−, green). Internal standard is shown in yellow and represents pooled total brain homogenate protein of three SOD1G93APrp+/+ and three SOD1G93APrp−/− male mice. The inserts show spots with significantly reduced abundance in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice later identified as GFAP. B: Quantification of GFAP immunoblots of spinal cord homogenates of terminally ill female mice (SOD1G93An = 4, SOD1G93APrp−/− n = 4, wild-type n = 10, Prp−/− n = 6) and (C) of male mice at disease onset (SOD1G93An = 7, SOD1G93APrp−/− n = 4, wild-type n = 7, Prp−/− n = 7). Underlying data were normalized against tubulin bands detected on the same blot after stripping of the membranes. Above the diagrams, representative blots for both disease stages and each genotype are shown. Asterisks in (B) and (C) indicate significant differences between two groups. (D-F) GFAP immunostaining of cervical spinal cord sections (7 μm) of a wild-type (D), a SOD1G93APrp+/+ (E), and of a SOD1G93APrp−/− mouse (F). Astrocytosis can be seen in both SOD1 transgenic mouse tissues. In areas undergoing massive vacuolization GFAP staining seems to be less intense in the Prp knockout (F, left panel). Focusing on areas with less vacuoles (F, right panel) there is no clear difference in density of GFAP staining or number of astrocyte cell bodies between SOD1G93A and SOD1G93APrp−/− tissues.

GFAP immunolabeling of paraffinized spinal cord sections revealed astrocytosis in both groups of SOD1G93A transgenic mice (Figure 4, D and E). There are regions with clearly less GFAP staining in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice (Figure 4F, left panel), as compared with SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice (Figure 4D). Here, the labeling seems to be more localized, concordant with shorter astrocytic extensions and stronger astrocyte activation in the presence of Prp. Areas with less GFAP staining in double transgenic mice are those with stronger vacuolization. Focusing on areas with vacuolization comparable with that of SOD1G93APrp+/+ tissue, there is no clear difference in labeling intensity or number of clearly visible astrocyte cell bodies (Figure 4E, right panel, compared with Figure 4D).

Spinal cords from final disease stage Prp+/+ and Prp−/− mice and from male mice at disease onset were analyzed for expression/activation levels of proteins suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of ALS.

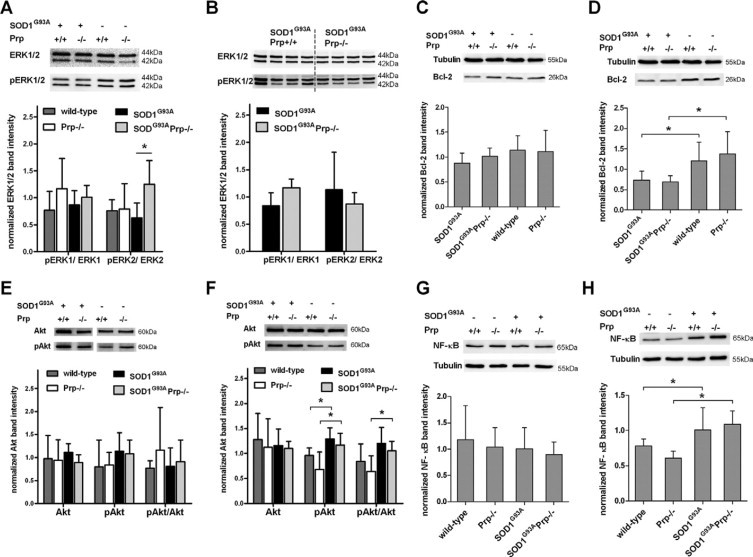

ERK2 Is Activated in SOD1G93APrp−/− Mice at Disease Onset

Interestingly, in ALS mice at disease onset, ERK2 is selectively activated in SOD1G93A mice when Prp was knocked out (P = 0.0159)(Figure 5A). This effect could not be observed in SOD1G93APrp+/+ transgenic mice compared with wild-type mice. ERK1 activation seems to be unaffected by expression of SOD1G93A. At terminal disease stage (Figure 5B), there was also no evidence of ERK1 regulation by Prp, and the difference in ERK2 activation determined at disease onset was lost.

Figure 5.

Representative immunoblots of spinal cord homogenates of male mice at disease onset, defined as time first clinical symptoms are visible, and of female mice at terminal disease stage. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Significant changes are indicated by asterisks. A: ERK1/2 expression at disease onset (n = 5 wild-type, n = 3 Prp−/−, n = 5 SOD1G93A, n = 4 SOD1G93APrp−/− mice), and (B) of terminal disease (n = 4 for each group). Diagrams show the ratio of band intensities of phosphorylated to unphosphorylated ERK. The pERK2/ERK2 ratio is significantly increased in SOD1G93A mice when Prp is knocked out (P = 0.0159). Relative Bcl-2 expression levels at disease onset (n = 4 wild-type, n = 6 Prp−/−, n = 3 SOD1G93A, n = 4 SOD1G93APrp−/−)(C) and at the end of disease (n = 4 each genotype) (D). In the terminal disease stage, Bcl-2 was significantly decreased in both SOD1G93A transgenic groups without differences due to Prp expression. E: Expression levels of Akt and pAkt and the ratio pAkt/Akt in wild-type (n = 3), Prp−/− (n = 4), SOD1G93A (n = 9), and SOD1G93APrp−/− (n = 6) male mice at disease onset. At the top, representative Akt and pAkt blots for each genotype are given as in (F), which illustrates the results obtained analyzing female mice of the terminal disease stage. pAkt is increased significantly in ALS mice, independently of Prp genotype (wild-type versus SOD1G93AP = 0.0153 and Prp−/− vs SOD1G93APrp−/− P = 0.0364). The ratio pAkt/Akt is significantly different only in the Prp−/− versus SOD1G93APrp−/− group (P = 0.0141). G and H: Representative NF-κB immunoblots and quantification of expression levels at disease onset (G) and at final disease stage (H), respectively. Analyzed were n = 4 wild-type, n = 3 Prp−/−, n = 6 SOD1G93A, and n = 6 SOD1G93APrp−/− male mice, and n = 3 wild-type, n = 3 Prp−/−, n = 7 SOD1G93A, and n = 6 SOD1G93APrp−/− female mice. At final disease, a significant induction of NF-κB could be observed in the Prp+/and Prp−/− group (wild-type versus SOD1G93AP = 0.0476 and Prp−/− versus SOD1G93APrp−/− P = 0.0083).

Bcl-2 expression levels tend to be lowered comparing male SOD1G93A mice with or without Prp at disease onset (Figure 5, C and D). At terminal disease, a trend toward decreased Bcl-2 levels could be detected in SOD1G93APrp+/+ (P = 0.0571 compared with wild-type) and significantly reduced levels in SOD1G93APrp−/− (P = 0.0286 compared with Prp−/−), but no significant differences were measurable comparing SOD1G93APrp with SOD1G93APrp−/− mice (Figure 5D).

Total Akt levels appear not to be regulated on expression of SOD1G93A at disease onset (Figure 5E). PhosphoAkt levels were increased at final disease stage SOD1G93A (P = 0.0153 compared with wild-type) or SOD1G93APrp−/− mice (P = 0.0364, as compared with Prp−/−)(Figure 5F). Akt activation expressed as the ratio pAkt/Akt is only marginally lower in Prp−/−, as compared with Prp+/+ mice, and the proportion of pAkt on total Akt is not influenced by Prp genotype (Figure 5F).

NF-κB levels are significantly elevated in final stage ALS mice of both Prp genotypes (SOD1G93APrp+/+ P = 0.0476 and SOD1G93APrp−/− P = 0.0083) compared with mice without the SOD1G93A transgene of the same age (Figure 5, G and H). We detected a trend toward lower NF-κB levels in prion knockout compared with wild-type mice. There is no difference due to Prp expression in the NF-κB levels in terminally ill ALS mice (Figure 5H) or at the time first clinical symptoms appear (Figure 5G).

Discussion

So far there is only limited data available on the involvement of Prp in neurodegenerative diseases other than prion disease. Up to now, mainly cell culture data or investigations on acute animal models have been available.28,29 However, especially for ALS, a pathophysiological role of Prp can be assumed.13

By cross-breeding of SOD1G93A transgenic mice with Prp-deficient mice, we generated a model that allows an examination of the involvement of Prp in the pathogenesis of ALS. Moreover, the model makes it possible to describe the function of Prp under stress conditions in vivo.

SOD1G93APrp−/− mice showed earlier disease symptoms, accelerated disease progression, and finally these mice died earlier than SOD1G93APrp+/+ mice, pointing to a protective effect of Prp in the ALS model. The slightly longer mean survival compared with published double-transgenic mice22 is probably due to lower SOD1G93A DNA content of our mice, as we were able to show that the survival times were about 30 days longer with a 40% reduction in the relative transgene content.

A detrimental effect by Prp knockout in SOD1G93A mice is most pronounced at disease onset and in the early disease phase, which was not only reflected by the aggravation of the clinical symptoms analyzed in the present study, but also by the proof of massively increased vacuolization in the anterior horn of spinal cord.

Several mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of ALS. These include oxidative stress and mitochondrial pathology, glutamate toxicity, reaction of glia cells and inflammation, growth factor deficiency, toxic effects by accumulation of protein aggregates, axonal transport defects and, as recently came into focus, defective RNA splicing.30

One of our hypotheses was that Prp is involved in detoxification of reactive oxygen species, as there was evidence of direct antioxidative properties of Prp in cell culture models.31 Our SOD activity assays of spinal cord homogenates confirmed that SOD1G93A not only exerts full Cu/ZnSOD function, but, in line with previous reports,27 increases Cu/ZnSOD activity 20-fold, which documents that not a loss of function, but achievement of a toxic gain-of-function occurs. Independently of the impact of Cu/ZnSOD activity in ALS, we observed no significant changes in SOD activity by deletion of Prp, so we conclude like others32 that Prp does not possess direct SOD activity or SOD regulating potency.

Although SOD activity is not influenced by Prp knockout, there seem to be increased levels of oxidative stress early in disease in ALS mice lacking Prp, since we observed a higher degree of vacuolization in the spinal cord, as compared with wild-type Prp ALS mice at disease onset. Vacuolization of mitochondria is the first morphological sign in spinal motor neurons in ALS model mice.33 Also the endoplasmic reticulum is discussed to be the place of origin of large vacuoles.34 Despite the factors leading to generation of large vacuoles and the place of origin still having to be clarified, it is clear that the development of vacuoles is closely linked to oxidative stress.35 As a result of ROS production, NF-κB is up-regulated or activated in neuronal36–38 and glial cells,39 tightly coupled to Bcl-2 down-regulation in neurones.38,40 Additionally, reduced NF-κB and elevated basal levels of cerebral Bcl-2 have been reported for Prp−/− mice.41 These data brought us to analyze whether the expression of these factors is influenced by the Prp-genotype in the ALS mouse model.

At disease onset, Bcl-2 levels tend to be lowered and are significantly decreased in spinal cord of SOD1G93A mice at terminal disease stage, while NF-κB is significantly increased at final disease stage. For both Bcl-2 and NF-κB, no influence of the expression levels on the Prp genotype could be found, therefore providing no evidence for an involvement of Prp in any of the pathways known to take part in ALS using Bcl-2 or NF-κB. Our analyses, however, do not allow any conclusions on the activation levels of NF-κB or Bcl-2 and, of course, it remains possible that Prp targets the subcellular localization of these factors and thus their activation levels, without changing the absolute expression levels.

By 2D-DIGE analysis we identified three proteins to be differentially expressed in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice at terminal disease stage: GFAP, creatine kinase (brain type), both binding partners of Prp,42 and DPYSL2. For all of these three proteins a connection to ALS can be assumed. Changed levels of creatine and creatine kinase activity are a sign of disturbed cellular energy balance, and a therapeutic benefit of creatine in neurodegenerative diseases including ALS has even been proposed.43 We assume that the increased levels of creatine kinase in the SOD1G93APrp−/− mice point to a regulation of energy balance by Prp. This assumption might even be supported by the secondary measurements of a slightly higher weight in Prp knockout mice. Another protein increased in Prp knockout is DPYSL2, also called calpain-mediated collapsin response mediator protein−2. This protein plays a role in neurite development and axonal outgrowth and has been suggested to play a role in neurodegeneration.44–46 Both creatine kinase and DPYSL2 seem to be changed by oxidative stress,47,48 and we presume that the difference detected in the expression levels of these proteins reflects a general phenomenon of decreased defense mechanisms against oxidative stress in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice.

More surprising in our view were the massively down-regulated GFAP levels in SOD1G93APrp−/− compared with SOD1G93A mice at final stage of disease. Attempts to verify this result by immunoblot and immunohistochemistry provided heterogeneous results. As demonstrated by immunoblot, GFAP levels were up-regulated early in disease, consistent with early astrogliosis elicited by SOD1G93A expression as published earlier.49 There was a tendency toward reduced GFAP levels in SOD1G93APrp−/− mice. Evaluation of spinal cord sections by GFAP immunohistochemistry revealed that there are in fact areas with less GFAP staining, mostly in regions of the anterior horn comprising lots of vacuoles. Comparing areas where less vacuolization is visible, the amount of GFAP staining and number of clearly visible astrocytes are in the same range.

Since we identified GFAP mass-spectrometrically from three isolated regulated 2D-gel spots via the amino acid sequence, we assume that these were post-translationally modified forms of GFAP, which could not be separately detected by the anti-GFAP antibody applied in immunoblot and immunohistochemistry.

The fact, however, that GFAP is not significantly increased by SOD1G93A expression in Prp−/− mice early in disease, as it is in Prp+/+ mice, points to an influence of Prp on astrocytic components protective for motor neurons, correlating with earlier disease onset and reduced numbers of motor neurons paralleled by enhanced vacuolization in spinal cord tissue.

Previous studies reveal astrocytosis in ALS mouse models and human ALS early in the course of the disease.8–11,21,50,51 Neuron-glia cross talk and its dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS, has increasingly come into focus recently.10,21,52,53 Interestingly and in line with our assumption, Prp expression in astrocytes modulates secreted factors and is secreted itself, promoting neuronal survival.15 Recently, Prp has also been demonstrated to regulate astrocyte development.16 Astrocytic Prp influences the deposition pattern of secreted laminin within the extracellular matrix and by that promotes neurite outgrowth.15,54 Interestingly, laminin was found to be up-regulated in ALS.55

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and the MEK pathway were found to be of importance in ALS, although reports on cell specificity are diverse. Loss of Akt phosphorylation was reported in motor neurons of human ALS and SOD1 transgenic mouse model before disease onset.56,57 Another study found that SOD1G93A mice do not lose the pro-survival PI3K/Akt signal nor increase it to suppress cell death mechanisms.53 For astrocytes it could be shown that oxidative stress response involves the PI3K/Akt pathway,58 while the MEK pathway also seems to be induced.59

In Prp−/− neuronal cells, lower PI3K-activity (Akt upstream) has been reported,60 which may be of relevance in neurodegenerative processes. In this model, ERK1/2 activity was not affected in Prp−/−, but was activated on a reduced level in brains of Prp overexpressing mice, whereas here, in contrast to Prp−/−, Akt was unchanged.61 We found Akt to be activated on SOD1G93A expression in SOD1G93A transgenic mice at terminal disease stage. This might be due to astrocyte signaling changes, because no changes in Akt phosphorylation could be detected in neurons of the spinal cord.53 However, we detected no influence of Prp on Akt or pAkt expression, arguing against a role of Akt activation in Prp's neuroprotective action.

Both cultured cerebellar neurons and the adult brains of Prp−/− mice showed significantly increased expression of phosphoERK,41 which we could not see in spinal cord homogenates. Consistent with reports on sustained activation of ERK1/2 on stress conditions like ischemia and glutamate induced toxicity,62 we were able to describe increased ERK2 activation at disease onset in our ALS model and propose that oxidative stress is the underlying event, because ERK2 is increased in neurons with oxidative damage.63 There are only limited data available on MEK-pathway activation state in astrocytes in ALS and it might be that Prp targets signaling pathways in different cell types. It was shown that ERK1/2 activation depends on the redox state of cells64; this property is perhaps more likely to be influenced by Prp than ERK1/2's apoptotic/anti-apoptotic function because of the unchanged Bcl-2 levels in spinal cord homogenates. From our data, we conclude that ERK2 activation contributes to the more severe disease progression in Prp−/− mice, either directly or, alternatively, as a cellular attempt to handle the more severe neurodegeneration.

Taken together, within the present study we document that Prp has a neuroprotective function in the SOD1G93A mouse ALS model. Prp deficiency leads to accelerated disease progression, increased vacuolization accompanied by decreased GFAP, pointing to a lower number or activation of glial cells, indicating that the glial cell may have a neuroprotective component when activated. From our data, it is most likely that loss of Prp function leads to diminished oxidative stress resistance, but not via regulation of SOD activity, survival signaling pathways of both neuronal and glial cells possibly being targeted.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Thomas Wirth and Dr. Bernd Baumann for their support. For technical assistance we thank Alice Pabst.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the Landesstiftung Baden-Württemberg (P-LS-Prot/42), and the European Commission (cNeupro, NeuroTAS, Anteprion).

Supplemental material for this article can be found on http://ajp.amjpathol.org.

Web Extra Material

(A) Diagrams of survival data of SOD1G93APrp+/+ and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice versus the normalized SOD1G93A DNA content determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Normalized mean content (± standard deviation) of SOD1G93A DNA in SOD1G93APrp+/+ and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice of the two groups of mice independently generated for the present study.

Kaplan Meier plot for disease onset (peak of body weight curve) (A) and onset of late disease (10% body weight loss) (B) in Prp+/+ or Prp−/− SOD1G93A transgenic male mice (n=12, respectively). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

2D-DIGE analysis: pixel volume distribution of the proteins 1–5 shown in supplemental table S2 from numbers 1–3 Prp−/− and numbers 1–3 Prp+/+ and average volume increase ratio.

Distribution of the four possible genotypes for male and female mice of the F2 generation raised from SOD1G93APrp+/− male and Prp+/− female mice from the F1 generation (= offspring of SOD1G93A♂ × Prp−/−♀).

2D-DIGE analysis and identification of selected proteins from brain homogenates of ALS mice expressing (Prp+/+) or lacking (Prp−/−) Prp.

References

- 1.Leigh PN, Swash M, Iwasaki Y, Ludolph A, Meininger V, Miller RG, Mitsumoto H, Shaw P, Tashiro K, Van Den Berg L. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a consensus viewpoint on designing and implementing a clinical trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Other Motor Neuron Disord. 2004;5:84–98. doi: 10.1080/14660820410020187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Rouleau GA. Oxidized/misfolded superoxide dismutase-1: the cause of all amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Ann Neurol. 2007;62:553–559. doi: 10.1002/ana.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urushitani M, Sik A, Sakurai T, Nukina N, Takahashi R, Julien JP. Chromogranin-mediated secretion of mutant superoxide dismutase proteins linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:108–118. doi: 10.1038/nn1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasinelli P, Houseweart MK, Brown RH, Jr, Cleveland DW. Caspase-1 and -3 are sequentially activated in motor neuron death in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase-mediated familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13901–13906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240305897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostic V, Jackson-Lewis V, de Bilbao F, Dubois-Dauphin M, Przedborski S. Bcl-2: prolonging life in a transgenic mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 1997;277:559–562. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5325.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Ona VO, Guegan C, Chen M, Jackson-Lewis V, Andrews LJ, Olszewski AJ, Stieg PE, Lee JP, Przedborski S, Friedlander RM. Functional role of caspase-1 and caspase-3 in an ALS transgenic mouse model. Science. 2000;288:335–339. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boillee S, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW. ALS: a disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron. 2006;52:39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pramatarova A, Laganiere J, Roussel J, Brisebois K, Rouleau GA. Neuron-specific expression of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 in transgenic mice does not lead to motor impairment. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3369–3374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03369.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Damme P, Bogaert E, Dewil M, Hersmus N, Kiraly D, Scheveneels W, Bockx I, Braeken D, Verpoorten N, Verhoeven K, Timmerman V, Herijgers P, Callewaert G, Carmeliet P, Van Den Bosch L, Robberecht W. Astrocytes regulate GluR2 expression in motor neurons and their vulnerability to excitotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14825–14830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705046104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamanaka K, Chun SJ, Boillee S, Fujimori-Tonou N, Yamashita H, Gutmann DH, Takahashi R, Misawa H, Cleveland DW. Astrocytes as determinants of disease progression in inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:251–253. doi: 10.1038/nn2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement AM, Nguyen MD, Roberts EA, Garcia ML, Boillee S, Rule M, McMahon AP, Doucette W, Siwek D, Ferrante RJ, Brown RH, Jr, Julien JP, Goldstein LS, Cleveland DW. Wild-type nonneuronal cells extend survival of SOD1 mutant motor neurons in ALS mice. Science. 2003;302:113–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1086071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilsland LG, Nirmalananthan N, Yip J, Greensmith L, Duchen MR. Expression of mutant SOD1 in astrocytes induces functional deficits in motoneuron mitochondria. J Neurochem. 2008;107:1271–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupuis L, Mbebi C, Gonzalez de Aguilar JL, Rene F, Muller A, de Tapia M, Loeffler JP. Loss of prion protein in a transgenic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:216–224. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westergard L, Christensen HM, Harris DA. The cellular prion protein (PrP[C]): its physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:629–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lima FR, Arantes CP, Muras AG, Nomizo R, Brentani RR, Martins VR. Cellular prion protein expression in astrocytes modulates neuronal survival and differentiation. J Neurochem. 2007;103:2164–2176. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arantes C, Nomizo R, Lopes MH, Hajj GN, Lima FR, Martins VR. Prion protein and its ligand stress inducible protein 1 regulate astrocyte development. Glia. 2009;57:1439–1449. doi: 10.1002/glia.20861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosokawa-Muto J, Kamatari YO, Nakamura HK, Kuwata K. Variety of anti-prion compounds discovered through an in silico screen based on PrPC structure: A correlation between anti-prion activity and binding affinity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:765–771. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01112-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinacker P, Schwarz P, Reim K, Brechlin P, Jahn O, Kratzin H, Aitken A, Wiltfang J, Aguzzi A, Bahn E, Baxter HC, Brose N, Otto M. Unchanged survival rates of 14–3-3gamma knockout mice after inoculation with pathological prion protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1339–1346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.4.1339-1346.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habisch HJ, Janowski M, Binder D, Kuzma-Kozakiewicz M, Widmann A, Habich A, Schwalenstocker B, Hermann A, Brenner R, Lukomska B, Domanska-Janik K, Ludolph AC, Storch A. Intrathecal application of neuroectodermally converted stem cells into a mouse model of ALS: limited intraparenchymal migration and survival narrows therapeutic effects. J Neural Transm. 2007;114:1395–1406. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0748-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludolph AC, Bendotti C, Blaugrund E, Hengerer B, Loffler JP, Martin J, Meininger V, Meyer T, Moussaoui S, Robberecht W, Scott S, Silani V, Van Den Berg LH. Guidelines for the preclinical in vivo evaluation of pharmacological active drugs for ALS/MND: report on the 142nd ENMC international workshop. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2007;8:217–223. doi: 10.1080/17482960701292837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boillee S, Yamanaka K, Lobsiger CS, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Kassiotis G, Kollias G, Cleveland DW. Onset and progression in inherited ALS determined by motor neurons and microglia. Science. 2006;312:1389–1392. doi: 10.1126/science.1123511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teuchert M, Fischer D, Schwalenstoecker B, Habisch HJ, Bockers TM, Ludolph AC. A dynein mutation attenuates motor neuron degeneration in SOD1(G93A) mice. Exp Neurol. 2006;198:271–274. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiltfang J, Smirnov A, Schnierstein B, Kelemen G, Matthies U, Klafki HW, Staufenbiel M, Huther G, Ruther E, Kornhuber J. Improved electrophoretic separation and immunoblotting of beta-amyloid (A beta) peptides 1-40, 1-42, and 1-43. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:527–532. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu NK, Xu XM. beta-tubulin is a more suitable internal control than beta-actin in western blot analysis of spinal cord tissues after traumatic injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1794–1801. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brechlin P, Jahn O, Steinacker P, Cepek L, Kratzin H, Lehnert S, Jesse S, Mollenhauer B, Kretzschmar HA, Wiltfang J, Otto M. Cerebrospinal fluid-optimized two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (2-D DIGE) facilitates the differential diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Proteomics. 2008;8:4357–4366. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jahn O, Hesse D, Reinelt M, Kratzin HD. Technical innovations for the automated identification of gel-separated proteins by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2006;386:92–103. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0592-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong PC, Borchelt DR. Motor neuron disease caused by mutations in superoxide dismutase 1. Curr Opin Neurol. 1995;8:294–301. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199508000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiarini LB, Freitas AR, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO J. 2002;21:3317–3326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spudich A, Frigg R, Kilic E, Kilic U, Oesch B, Raeber A, Bassetti CL, Hermann DM. Aggravation of ischemic brain injury by prion protein deficiency: role of ERK-1/-2 and STAT-1. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lagier-Tourenne C, Cleveland DW. Rethinking ALS: the FUS about TDP-43. Cell. 2009;136:1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown DR, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. Prion protein-deficient cells show altered response to oxidative stress due to decreased SOD-1 activity. Exp Neurol. 1997;146:104–112. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones S, Batchelor M, Bhelt D, Clarke AR, Collinge J, Jackson GS. Recombinant prion protein does not possess SOD-1 activity. Biochem J. 2005;392:309–312. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dal Canto MC, Gurney ME. Development of central nervous system pathology in a murine transgenic model of human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1271–1279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dal Canto MC, Gurney ME. A low expressor line of transgenic mice carrying a mutant human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene develops pathological changes that most closely resemble those in human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93:537–550. doi: 10.1007/s004010050650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata N. Transgenic mouse model for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with superoxide dismutase-1 mutation. Neuropathology. 2001;21:82–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2001.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang YM, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi Y, Yoshihara T, Liang Y, Terao S, Takeuchi H, Ishigaki S, Katsuno M, Adachi H, Niwa J, Tanaka F, Doyu M, Yoshida M, Hashizume Y, Sobue G. Gene expression profile of spinal motor neurons in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:236–251. doi: 10.1002/ana.20379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casciati A, Ferri A, Cozzolino M, Celsi F, Nencini M, Rotilio G, Carri MT. Oxidative modulation of nuclear factor-kappaB in human cells expressing mutant fALS-typical superoxide dismutases. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1019–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferlazzo N, Condello S, Curro M, Parisi G, Ientile R, Caccamo D. NF-kappaB activation is associated with homocysteine-induced injury in Neuro2a cells. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jang MH, Jung SB, Lee MH, Kim CJ, Oh YT, Kang I, Kim J, Kim EH. Melatonin attenuates amyloid beta25–35-induced apoptosis in mouse microglial BV2 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vukosavic S, Stefanis L, Jackson-Lewis V, Guegan C, Romero N, Chen C, Dubois-Dauphin M, Przedborski S. Delaying caspase activation by Bcl-2: a clue to disease retardation in a transgenic mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9119–9125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09119.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown DR, Nicholas RS, Canevari L. Lack of prion protein expression results in a neuronal phenotype sensitive to stress. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:211–224. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrakis S, Sklaviadis T. Identification of proteins with high affinity for refolded and native PrPC. Proteomics. 2006;6:6476–6484. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adhihetty PJ, Beal MF. Creatine and its potential therapeutic value for targeting cellular energy impairment in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuromolecular Med. 2008;10:275–290. doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8053-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chung MA, Lee JE, Lee JY, Ko MJ, Lee ST, Kim HJ. Alteration of collapsin response mediator protein-2 expression in focal ischemic rat brain. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1647–1653. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000176520.49841.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshida H, Watanabe A, Ihara Y. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 is associated with neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer's disease. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9761–9768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Ottens AK, Sadasivan S, Kobeissy FH, Fang T, Hayes RL, Wang KK. Calpain-mediated collapsin response mediator protein-1, -2, and -4 proteolysis after neurotoxic and traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:460–472. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cole AR, Noble W, van Aalten L, Plattner F, Meimaridou R, Hogan D, Taylor M, LaFrancois J, Gunn-Moore F, Verkhratsky A, Oddo S, LaFerla F, Giese KP, Dineley KT, Duff K, Richardson JC, Yan SD, Hanger DP, Allan SM, Sutherland C. Collapsin response mediator protein-2 hyperphosphorylation is an early event in Alzheimer's disease progression. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1132–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ilzecka J, Stelmasiak Z. Creatine kinase activity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:286–287. doi: 10.1007/s10072-003-0158-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levine JB, Kong J, Nadler M, Xu Z. Astrocytes interact intimately with degenerating motor neurons in mouse amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Glia. 1999;28:215–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall ED, Oostveen JA, Gurney ME. Relationship of microglial and astrocytic activation to disease onset and progression in a transgenic model of familial ALS. Glia. 1998;23:249–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199807)23:3<249::aid-glia7>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nagai M, Re DB, Nagata T, Chalazonitis A, Jessell TM, Wichterle H, Przedborski S. Astrocytes expressing ALS-linked mutated SOD1 release factors selectively toxic to motor neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:615–622. doi: 10.1038/nn1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beers DR, Henkel JS, Xiao Q, Zhao W, Wang J, Yen AA, Siklos L, McKercher SR, Appel SH. Wild-type microglia extend survival in PU. 1 knockout mice with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16021–16026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607423103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peviani M, Cheroni C, Troglio F, Quarto M, Pelicci G, Bendotti C. Lack of changes in the PI3K/AKT survival pathway in the spinal cord motor neurons of a mouse model of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:592–602. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freire E, Gomes FC, Linden R, Neto VM, Coelho-Sampaio T. Structure of laminin substrate modulates cellular signaling for neuritogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4867–4876. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wiksten M, Vaananen A, Liesi P. Selective overexpression of gamma1 laminin in astrocytes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis indicates an involvement in ALS pathology. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:2045–2058. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dewil M, Lambrechts D, Sciot R, Shaw PJ, Ince PG, Robberecht W, Van den Bosch L. Vascular endothelial growth factor counteracts the loss of phospho-Akt preceding motor neurone degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33:499–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kieran D, Sebastia J, Greenway MJ, King MA, Connaughton D, Concannon CG, Fenner B, Hardiman O, Prehn JH. Control of motoneuron survival by angiogenin. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14056–14061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3399-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee ES, Yin Z, Milatovic D, Jiang H, Aschner M. Estrogen and tamoxifen protect against Mn-induced toxicity in rat cortical primary cultures of neurons and astrocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2009;110:156–167. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung YH, Joo KM, Lim HC, Cho MH, Kim D, Lee WB, Cha CI. Immunohistochemical study on the distribution of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) in the central nervous system of SOD1G93A transgenic mice. Brain Res. 2005;1050:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vassallo N, Herms J, Behrens C, Krebs B, Saeki K, Onodera T, Windl O, Kretzschmar HA. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase by cellular prion protein and its role in cell survival. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;332:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weise J, Doeppner TR, Muller T, Wrede A, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Zerr I, Witte OW, Bahr M. Overexpression of cellular prion protein alters postischemic Erk1/2 phosphorylation but not Akt phosphorylation and protects against focal cerebral ischemia. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2008;26:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stanciu M, Wang Y, Kentor R, Burke N, Watkins S, Kress G, Reynolds I, Klann E, Angiolieri MR, Johnson JW, DeFranco DB. Persistent activation of ERK contributes to glutamate-induced oxidative toxicity in a neuronal cell line and primary cortical neuron cultures. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12200–12206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perry G, Roder H, Nunomura A, Takeda A, Friedlich AL, Zhu X, Raina AK, Holbrook N, Siedlak SL, Harris PL, Smith MA. Activation of neuronal extracellular receptor kinase (ERK) in Alzheimer disease links oxidative stress to abnormal phosphorylation. Neuroreport. 1999;10:2411–2415. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199908020-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chu CT, Levinthal DJ, Kulich SM, Chalovich EM, DeFranco DB. Oxidative neuronal injury. The dark side of ERK1/2. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2060–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Diagrams of survival data of SOD1G93APrp+/+ and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice versus the normalized SOD1G93A DNA content determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. (B) Normalized mean content (± standard deviation) of SOD1G93A DNA in SOD1G93APrp+/+ and SOD1G93APrp−/− mice of the two groups of mice independently generated for the present study.

Kaplan Meier plot for disease onset (peak of body weight curve) (A) and onset of late disease (10% body weight loss) (B) in Prp+/+ or Prp−/− SOD1G93A transgenic male mice (n=12, respectively). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

2D-DIGE analysis: pixel volume distribution of the proteins 1–5 shown in supplemental table S2 from numbers 1–3 Prp−/− and numbers 1–3 Prp+/+ and average volume increase ratio.

Distribution of the four possible genotypes for male and female mice of the F2 generation raised from SOD1G93APrp+/− male and Prp+/− female mice from the F1 generation (= offspring of SOD1G93A♂ × Prp−/−♀).

2D-DIGE analysis and identification of selected proteins from brain homogenates of ALS mice expressing (Prp+/+) or lacking (Prp−/−) Prp.