Abstract

In this article, the current and potential clinical roles of 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging are presented, with a focus on applications to prostate cancer and hyperpolarized 13C spectroscopic imaging. The advantages of 13C MRS have been its chemical specificity and lack of background signal, with the major disadvantage being its inherently low sensitivity and the subsequent inability to acquire data at a high-enough spatial and temporal resolution to be routinely applicable in the clinic. The approaches to improving the sensitivity of 13C spectroscopy have been to perform proton decoupling and to use endogenous 13C-labeled or enhanced metabolic substrates. With these nominal increases in signal-to-noise ratio, 13C MRS using labeled metabolic substrates has shown diagnostic promise in patients and has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The development of technology that applies dynamic nuclear polarization to generate hyperpolarized 13C-labeled metabolic substrates, and the development of a process for delivering them into living subjects, have totally changed the clinical potential of MRS of 13C-labeled metabolic substrates. Preliminary preclinical studies in a model of prostate cancer have demonstrated the potential clinical utility of hyperpolarized 13C MRS.

Keywords: molecular imaging, MRI, 13C, magnetic resonance, spectroscopy

In contrast to anatomic MRI, which detects changes in the relaxivity or density of bulk tissue water, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) can noninvasively detect multiple small, endogenous molecular-weight metabolites within cells or extracellular spaces associated with several metabolic pathways that have been shown to significantly change in prostate cancer (1,2). The clinical use of spectroscopy as an adjunct to MRI has expanded dramatically over the past several years because of recent technical advances in hardware and software that have improved the spatial and time resolution of spectral data and have resulted in the incorporation of this technology on commercial MRI scanners. However, because of sensitivity and MRI scanner hardware issues, most clinical MRI/MRS studies have involved a combination of MRI and proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) (1H MRSI) (1,2). Hyperpolarized 13C-labeled metabolic substrates have the potential to revolutionize the way we use MRSI for assessing prostate cancer. 13C-labeled substrates polarized via dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) can provide tens of thousandfold enhancement of the 13C NMR signals of the substrate and its subsequent metabolic products. Because of both the unique chemical properties of the 13C nucleus and the dramatic improvement in spectroscopic sensitivity provided by DNP, the use of hyperpolarized 13C-labeled substrates will potentially allow us to assess, in patients, changes in metabolic fluxes through glycolysis, citric acid cycle, and fatty acid synthesis that significantly change in prostate cancer and are not currently obtainable by 1H MRSI.

CLINICAL 13C MRS USING 13C-LABELED SUBSTRATES

13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy allows observation of the backbone of organic compounds, yielding specific information about the identity and structure of biologically important compounds. Another advantage is the large chemical shift range for carbon (≈250 ppm), compared with that for protons (≈15 ppm), allowing improved resolution of for metabolites that cannot be resolved in proton NMR spectra of tissue. However, clinical 13C spectroscopy has been limited by its low natural abundance of 13C (1.1%) and its low magnetogyric ratio (γ of 13C is one quarter that of 1H).

One way to improve the sensitivity of 13C spectroscopy is to perform a technique known as proton (1H) decoupling. Without proton decoupling, NMR signals from 13C nuclei are split by attached 1H nuclei into (n + 1) peaks, where n is the number of 1H nuclei attached to the 13C nucleus. The signal-to-noise ratio of 13C resonances can be significantly increased by eliminating these couplings by irradiating the entire 1H NMR absorption range (called proton decoupling), consequently collapsing 13C resonances to singlets, with an additional enhancement in 13C signal-to-noise ratio being obtained from a phenomenon known as the nuclear Overhauser effect (3).

Another way to improve the sensitivity of 13C MRS is to introduce a 13C label into a metabolic substrate. Replacing the 12C (98.9% natural abundance) isotope with the 13C isotope at a specific carbon or carbons in a metabolic substrate does not affect its biochemistry. After administration in cells, animals, or even humans, the uptake of the 13C-labeled substrate and incorporation of the 13C label into metabolites can be monitored without interference from background signals. Despite a low inherent signal-to-noise ratio, 13C MRS using labeled substrates has shown diagnostic promise in patients (4-7) but has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Specifically, 13C neurochemical data have contributed to the understanding of Alzheimer’s disease, Canavan disease, mitochondrial and hepatic encephalopathy, epilepsy, childhood leukodystrophy, schizophrenia, and normal brain development (4-7). Some of these clinical studies have further improved the sensitivity of 13C MRS by applying the high sensitivity of 1H MRS using sophisticated data acquisition schemes that detect only 1H attached to 13C labels within molecules (4).

Although in vivo 13C MRS has not been used in studies of patients with prostate cancer, preliminary studies have suggested its clinical potential. In a high-resolution, proton-decoupled natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra of unprocessed human pathology specimens of prostate tumors and adjacent nonneoplastic control tissues, metabolic changes were identified that distinguished prostate cancer from benign prostatic hyperplasia. In particular, the tumors contained larger amounts of triacylglycerols, smaller amounts of citrate, and acidic mucins. It was proposed that the transformation-associated deviations from the normally high amounts of citrate and low amounts of lipids in the prostate were consistent with an alteration in either the concentration or the activity of adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase in the tumors (8). Two subsequent studies attempted to translate 13C NMR studies to the clinic (9,10). In the first study, proton-coupled natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra were acquired from a 4 × 4 × 4 cm region of normal human prostate using a depth-resolved surface-coil spectroscopy sequence and a dual-tuned, concentric 1H/13C 20-cm-diameter transmit and 7.5-cm-diameter receive surface coils in a clinical 1.5-T MRI scanner (8). It was concluded that although citrate could be detected in the natural-abundance 13C NMR spectra of the normal human prostate, more sensitive techniques involving proton decoupling and the use of 13C-labeled citrate precursors may be necessary to attain clinically relevant data (9). In the second study, proton-enhanced 13C imaging or spectroscopy was performed on phantoms and ex vivo human prostate specimens using polarization transfer techniques in which the sensitivity of the carbon signal was enhanced by transferring the proton spin order to the attached carbon (10).

Certainly, another consideration of using 13C-labeled metabolic substrates in clinical studies is the cost of having these labeled compounds synthesized, particularly since physiologic, rather than tracer, doses need to be administered. The cost for the synthesis of a new 13C-labeled metabolic probe is initially high but dramatically reduces with demand for its production. A good example is the pricing for d-glucose-13C6. Around 15 years ago, the market price for this d-glucose-13C6 was about $500/g. Because of increased demand and improvements in the synthesis, the current pricing for d-glucose-13C6 is less than $100/g.

HYPERPOLARIZED 13C SPECTROSCOPIC IMAGING

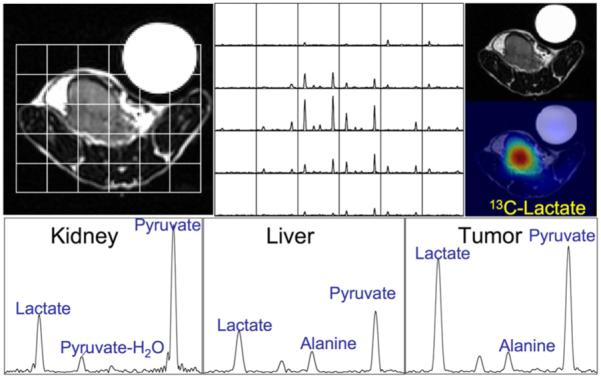

The development of technology that applies DNP to generate hyperpolarized 13C agents and a dissolution process that prepares them for injection into living subjects has totally changed the clinical potential of MRS of 13C-labeled substrates. The prototype DNP polarizer that was designed in Malmo, Sweden (11-13), has been shown to enhance the signal by more than 10,000-fold for detecting 13C probes of endogenous, nontoxic, nonradioactive substances such as pyruvate and to have the potential for monitoring fluxes through multiple key biochemical pathways such as glycolysis (14,15), the citric acid cycle (16), and fatty acid synthesis (17,18). Pyruvate is ideal for these studies: The signal from C-1 carbon relaxes slowly as a result of its long T1, and C-1 carbon is at the entry point to several important energy and biosynthesis pathways. Preliminary studies that were performed in a whole-body MRI scanner at 1.5 T in rat kidney (19) and in tumors (20,21) have confirmed that [1-13C]pyruvate is delivered to tissues and converted to alanine, lactate, and bicarbonate with a spatial distribution and time course that varies according to the tissue of interest (Fig. 1).

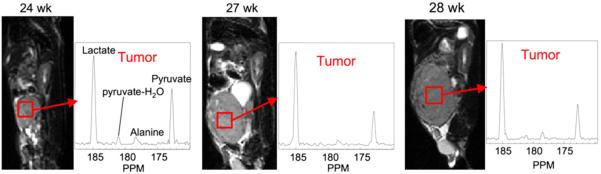

FIGURE 1.

Selected spectra from a 3D 8 × 8 × 16 array of 13C MRSI data acquired in 14 s at 3 T demonstrate dramatic increases in 13C lactate signals in a transgenic prostate tumor after injection of 13C pyruvate that was prepolarized in HyperSense system (Oxford Instruments). Lactate SNR was measured to be 59.9 in kidney and 115.9 in tumor.

Although the current commercially available clinical MRI/1H MRSI prostate examination relies on changes in choline, citrate, and polyamine metabolism, lactate and alanine have largely been ignored because of the difficulty of suppressing the large signals from periprostatic lipids, which overlap lactate and alanine. Significantly higher concentrations of lactate and alanine have recently been found in biopsy samples of prostate cancer, compared with biopsy samples of healthy tissue (22). High levels of lactate in cancer are also consistent with the findings of prior studies and have been associated with increased glycolysis and cell membrane biosynthesis (14,23). 18F-FDG PET studies have shown that rates of glucose uptake in several human cancers are high and that the glucose uptake correlates directly with the aggressiveness of the disease and inversely with the patient’s prognosis (24). The high glucose uptake leads to increased lactate production in most tumors even though some have sufficient oxygen, a condition known as the Warburg effect (25) or aerobic glycolysis (23). The increased glycolysis provides the parasitic cancer cells with an energy source, a carbon source for the biosynthesis of cell membranes that begins with lipogenesis (14), and an acid source that likely enables the cells to invade neighboring tissue (23). The high sensitivity of hyperpolarized 13C MRS and its ability to monitor [1-13C]pyruvate and its metabolic products (lactate and alanine) have the potential to significantly improve the characterization of prostate cancer.

HYPERPOLARIZED 13C MRSI IN A PRECLINICAL MODEL OF PROSTATE CANCER

The first dynamic hyperpolarized 13C spectroscopic imaging studies of prostate cancer were performed at various stages of progression using the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate (TRAMP) model (20). The 13C metabolic imaging data were acquired using a fast 3-dimensional (3D) MRSI sequence that provided 3D 13C MRSI at a resolution of 0.135 cm3 in 10 s. Preliminary studies clearly demonstrated the feasibility of obtaining high-spatial-resolution 13C MRSI data with a high signal-to-noise ratio from TRAMP mice by injecting the animals with hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Different 13C metabolic characteristics were observed in mouse kidney, liver, and prostate tumor (Fig. 1). Serial 13C 3D MRSI data acquired from the same TRAMP mouse clearly demonstrated that high levels of lactate were produced from hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate in prostate cancer and that lactate production increased with disease progression (Fig. 2) (20). These studies demonstrated the feasibility of the technology to provide noninvasive biomarkers for characterizing prostate cancer tumor aggressiveness at an unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution and the potential for serially monitoring disease progression using hyperpolarized 13C metabolite imaging.

FIGURE 2.

Serial studies of same TRAMP mouse demonstrate ability to follow disease progression in this transgenic model of prostate cancer. All 13C MRSI data were acquired in 14 s using 3D double spin-echo flyback echoplanar spectroscopic imaging sequence (20) with TR of 215 ms, variable spin echo, and spatial resolution of 0.135 cm3. This new technique is seen to be feasible for following disease progression and monitoring therapeutic response in preclinical cancer models.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that proton-decoupled 13C MRS using 13C-labeled metabolic substrates has potential in both preclinical and clinical MRS studies on understanding prostate cancer and the diseases of other organs. The advantages of 13C MRS have been its chemical specificity and lack of background signal, with the major disadvantage being its inherent insensitivity and the subsequent inability to acquire data at a high-enough spatial and temporal resolution to be routinely applicable in the clinic. These disadvantages have also meant that MRI scanner manufacturers have not made standard clinical MRI scanners that can perform 13C MRS. The addition of the ability to detect nuclei other than 1H represents an added cost, and the clinical motivation to date has not been adequately demonstrated. The development of technology that applies DNP to generate hyperpolarized 13C agents and a dissolution process that prepares them for injection into living subjects has totally changed the clinical potential of MRS of 13C-labeled metabolic substrates. This excitement has been fueled by the encouraging results of studies involving fast 13C MRSI of prepolarized 13C metabolic substrates in preclinical models of prostate cancer. There clearly remain several technologic hurtles, but the potential is truly amazing.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by NIH grants R21EB05363 and R01EB007588 and UC Discovery grants LSIT01-10107 and ITL-BIO04-10148.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kurhanewicz J, Swanson MG, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB. Combined magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopic imaging approach to molecular imaging of prostate cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:451–463. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajesh A, Coakley FV, Kurhanewicz J. 3D MR spectroscopic imaging in the evaluation of prostate cancer. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:921–929. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Overhauser A. Paramagnetic relaxation in metals. Phys Rev. 1953;89:689. [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Patel AB, Behar KL, Rothman DL. In vivo 1H-[13C]-NMR spectroscopy of cerebral metabolism. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:339–357. doi: 10.1002/nbm.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruetter R, Adriany G, Choi IY, Henry PG, Lei H, Oz G. Localized in vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy of the brain. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:313–338. doi: 10.1002/nbm.841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross B, Lin A, Harris K, Bhattacharya P, Schweinsburg B. Clinical experience with 13C MRS in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:358–369. doi: 10.1002/nbm.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F, Shulman RG. In vivo NMR studies of the glutamate neurotransmitter flux and neuroenergetics: implications for brain function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:401–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halliday KR, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Sillerud LO. Differentiation of human tumors from nonmalignant tissue by natural-abundance 13C NMR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 1988;7:384–411. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sillerud LO, Halliday KR, Griffey RH, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Sheppard S. In vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy of the human prostate. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:224–230. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanson SD, Quint LE, Yeung HN. Proton-enhanced 13C imaging/spectroscopy by polarization transfer. Magn Reson Med. 1990;15:102–111. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910150111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, et al. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golman K, Olsson LE, Axelsson O, Mansson S, Karlsson M, Petersson JS. Molecular imaging using hyperpolarized 13C. Br J Radiol. 2003;76(spec no 2):S118–S127. doi: 10.1259/bjr/26631666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolber J, Ellner F, Fridlund B, et al. Generating highly polarized nuclear spins in solution using dynamic nuclear polarization. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res A. 2004;526:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costello LC, Franklin RB. “Why do tumour cells glycolyse?”: from glycolysis through citrate to lipogenesis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;280:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-8841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA. Adaptive landscapes and emergent phenotypes: why do cancers have high glycolysis? J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2007;39:251–257. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9085-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Citrate metabolism of normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. Urology. 1997;50:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhajda FP. Fatty acid synthase and cancer: new application of an old pathway. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5977–5980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swinnen JV, Brusselmans K, Verhoeven G. Increased lipogenesis in cancer cells: new players, novel targets. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2006;9:358–365. doi: 10.1097/01.mco.0000232894.28674.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler SJ, Yen Y, Wolber J, et al. In vivo 13 carbon metabolic imaging at 3T with hyperpolarized 13C-1-pyruvate. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:65–69. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen AP, Albers MJ, Cunningham CH, et al. Hyperpolarized C-13 spectroscopic imaging of the TRAMP mouse at 3T: initial experience. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1099–1106. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golman K, Zandt RI, Lerche M, Pehrson R, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Metabolic imaging by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging for in vivo tumor diagnosis. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10855–10860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tessem M, Keshari K, Joun D, et al. Lactate and alanine: metabolic biomarkers of prostate cancer determined using 1H HR-MAS spectroscopy of biopsies; Paper presented at: Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB; Berlin, Germany. May 19–25, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunkel M, Reichert TE, Benz P, et al. Overexpression of Glut-1 and increased glucose metabolism in tumors are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1015–1024. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. Über den Stoffwechsel von Tumoren im Körper. Klin Woch. 1926;5:829–832. [Google Scholar]