Abstract

Background

Low rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) screening persist due to individual, provider and system level barriers.

Purpose

To develop and obtain initial feedback about a CRC screening educational video from community members and medical professionals.

Methods

Focus groups of patients were conducted prior to the development of an educational video and focus groups of patients provided initial feedback about the developed CRC screening educational video. Medical personnel reviewed the video and made recommendations prior to final editing of the video.

Results

Patients identified CRC screening barriers and made suggestions about the information to include in the educational video. Their suggestions included using a healthcare provider to state the importance of completing CRC screening, demonstrate how to complete the fecal occult blood test, and that men and women from diverse ethnic groups and races could be included in the same video. Participants reviewed the developed video and mentioned that their suggestions were portrayed correctly, the video was culturally appropriate, and the information presented in the video was easy to understand. Medical personnel made suggestions on ways to improve the content and the delivery of the medical information prior to final editing of the video.

Discussion

Participants provided valuable information in the development of an educational video to improve patient knowledge and patient-provider communication about CRC screening. The educational video developed was based on the Protection Motivation Theory and addressed the colon cancer screening barriers identified in this mostly minority and low-income patient population. Future research will determine if CRC screening increases among patients who watch the educational video.

Translation to Health Education Practice

Educational videos can provide important information about CRC and CRC screening to average-risk adults.

Keywords: colorectal cancer screening, patient education, patient-provider communication, health disparities, protection motivation theory

BACKGROUND

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading type of cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States.1 National policy-making expert organizations appreciate the importance of CRC screening and support a variety of CRC screening tests among average-risk adults who are age 50 years and older.2–4 These screening guidelines are based on evidence that screening decreases CRC incidence and mortality.2–6 However, even with these recommended guidelines for CRC screening, barriers exist to widespread utilization. According to the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, of adults aged 50 and older, only 24.1% had a blood stool test within the past two years and 57.1% had ever had a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.7 In addition, CRC screening rates are lower among minority and low socioeconomic populations.8

In general, low CRC screening rates are due to patient, provider, and system level factors.9–22 Previous behavioral interventions directed at the patient have focused on increasing awareness and improving knowledge about CRC screening, and although these interventions have increased screening rates, a significant number of average risk adults are still not completing CRC screening tests.17 Physician recommendation or discussion about CRC screening has been shown to be a significant facilitator of patient completion of CRC screening tests.10, 23, 24 The problem, however, is that physicians often fail to mention CRC screening to patients because of limited time, forgetfulness, and competing medical issues associated with the patient visit.19–21, 25, 26 Additionally, patients often do not seek information during a medical visit and when they do seek information they often do so indirectly.27

There is also evidence that suggests that low-income patients with inadequate health literacy have less CRC knowledge and have lower rates of completing CRC screening within guidelines.9, 28 Previous studies have demonstrated that educational videos including narratives and patient testimonials have increased mammography and cervical cancer screening rates among minority and low-income patients.29, 30 Therefore, to significantly increase CRC screening rates among minority and low income patients, behavioral interventions directed at the patient level should consider forms of communication other than print material, such as an educational video that includes using a narrative to both improve CRC screening knowledge and facilitate patient-provider communication about screening. A strategy to accomplish this may be by activating the patient to ask their healthcare provider for a CRC screening test.

PURPOSE

The goals of this study were to: 1) understand the specific CRC screening barriers that patients of an urban neighborhood health center experience, 2) identify the patient-provider communication issues associated with completing CRC screening, 3) obtain input about the messages that should be included in an educational video to facilitate patients to communicate with their providers about CRC screening, and 4) obtain initial feedback about educational video focusing on clarity, accuracy, message delivery, and cultural appropriateness from community members and medical professionals.

METHODS

Prior to developing an educational video, focus groups of patients were conducted concentrating on barriers to CRC screening and provider-patient communication issues associated with undergoing CRC screening. Additional focus groups of the same patients were conducted after initial video production to determine if the patient-centered objectives were accomplished. In-depth reviews of the video were also conducted with medical personnel to ensure accuracy of the medical information. The Institutional Review Board of the ____ University approved the protocol for this study.

Focus group guides

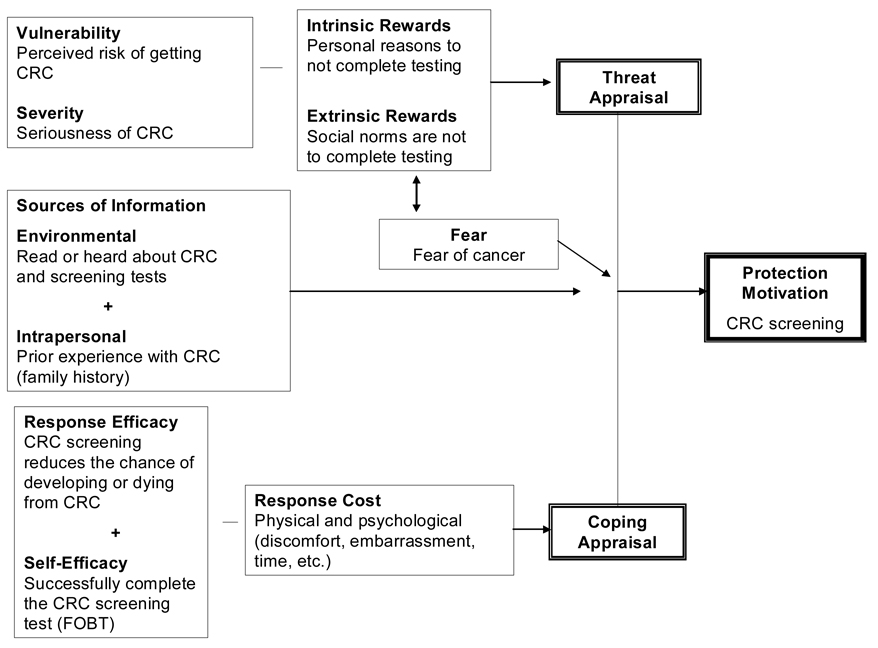

Focus group guides developed were based on the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT).31 According to the PMT, the contradictory impact of threatening information (threat appraisal) followed by a coping appraisal influences an individual’s decision to react to the health information. Threat appraisal and coping appraisal are two parallel cognitive processes that result in protection motivation (completion of CRC screening; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Protection Motivation Theory Applied To Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Screening Rogers RW. Protection Motivation Theory, 1997.

The threat appraisal factors evaluate the maladaptive response (not completing CRC screening). The threat appraisal factors that decrease the maladaptive response include the perceived severity of the disease (CRC is a serious disease) and the perceived vulnerability (perceived risk of getting CRC). Any perceived rewards (intrinsic and extrinsic) of not performing CRC screening will increase the likelihood of the maladaptive response. For example, not completing CRC screening avoids the diagnosis of colon cancer. Coping appraisal factors evaluate the adaptive response (completing CRC screening). The coping appraisal factors include the summation of the perceived response efficacy (completing CRC screening will reduce my chance of developing or dying from CRC) and the perceived self-efficacy (I will be able to complete CRC screening) minus the response costs (physical, psychological, financial) associated with completing the CRC screening test. In addition, the PMT also includes fear as an emotional process that indirectly affects perceived severity, and personal (family history of CRC) and environmental sources (read about CRC testing) of information.

The focus group guide also addressed the four main components of patient-provider communication during a medical visit included in the PACE (Presenting information, Asking questions, Checking for understanding, Expressing concerns) communication system.27, 32, 33 For CRC screening, the components consisted of presenting information (patient brings up CRC screening because of his/her age), asking questions (questions about CRC screening tests and test procedures), checking understanding (patient checks his/her understanding of the information provided by the healthcare provider regarding how to complete the CRC test, when results will be provided), and expressing emotions or concerns (desires CRC screening, concerns about fear of a positive CRC screening test or fear of a cancer diagnosis).

The focus group questions concentrated on the key constructs of the PMT theory and the components of the PACE communication system. Although discussion of any CRC screening test could be explored during the focus groups, the discussion was focused on the fecal occult blood test (FOBT). This was done because the FOBT was the screening test recommended for average-risk patients by the providers of the neighborhood health center. Focus group questions that guided discussion included sources of information, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, perceived risk and severity of CRC, fear of CRC, response and self-efficacy, CRC screening response cost, system level issues, and patient-provider communication issues (Table 1). Additionally, ideas were sought about what information should be included in an educational program designed to promote CRC screening. The focus group guide was developed and refined by members of the research team using previous experience and after reviewing the literature.

Table 1.

Examples of focus group questions based on the Protection Motivation Theory

| Theory Construct | Example Of Questions |

|---|---|

| Threat Appraisal | |

| Intrinsic rewards | What are the reasons that help you make the decision to complete or not complete a colon cancer screening test? |

| Extrinsic rewards | What do you think your family members would think if you completed or did not complete a colon cancer screening test? |

| Vulnerability | Do you think you are more or less likely to get colon cancer than other people your age? |

| Severity | Do you think colon cancer is serious? |

| Fear | Do you have any concerns about colon cancer? |

| Sources of Information | |

| Environmental | Have you seen anything about colon cancer on TV? |

| Intrapersonal | Have you had a family member or a friend be diagnosed with colon cancer? |

| Coping Appraisal | |

| Response-efficacy | What do you think are some of the advantages and disadvantages of completing a colon cancer screening test? |

| Self-efficacy | Do you think completing a colon cancer screening test would be easy or difficult? |

| Response cost | Do you have any thoughts or concerns about completing a colon cancer screening test? |

| System-level | Are there any issues about the clinic that you think would help patients complete a colon cancer screening test? |

| Patient-provider communication | Has your doctor or a nurse ever talked to you about colon cancer screening? |

Participant recruitment

For the initial three focus groups, members of the research team recruited patients in the waiting room of a local neighborhood health center. The health center is one of five federally qualified health centers located in the city. A large proportion of the patients are from minority and low-income (primarily African-American and Latino) populations. Patient eligibility criteria for this study included: 1) age 50 years or older, 2) English speaking, 3) no previous diagnosis of colon cancer, and 4) a regular patient of the health center (previous medical visit in the past two years). These eligibility criteria permitted us to include patients who typically used the health centers. The receptionist notified us of all age-appropriate patients, who we approached and asked to participate in a one hour focus group discussion about colon cancer screening. Over eight days, 53 individuals were approached by members of the research team who used a script to introduce themselves and to obtain patient interest in participating in the study. Twelve individuals were not eligible because they were not regular patients of the health center (n=8) or did not speak English (n=4). Of the remaining 41 individuals, 26 refused (16 were not interested in participating, 4 were too sick, 3 had transportation issues, 3 could not be present on the days/times of the focus groups) and 15 patients agreed to participate.

In addition to the three initial focus groups, two patient focus groups were conducted after the CRC screening educational video was developed. Patients who participated in the initial focus groups were also asked to participate in additional focus groups to review the educational video and to provide feedback to ensure that their suggestions and concerns were incorporated in the video.

Focus groups and In-depth interviews

The focus groups were led by a trained female moderator, and field notes of salient points and group dynamics were recorded by a staff member. The focus groups lasted approximately 60 minutes and were audio recorded. All focus groups’ discourse was transcribed verbatim, and the transcripts were reviewed for accuracy. The participants received a $25 gift card to a local grocery store in appreciation of their time for each focus group they attended.

Two sessions were conducted post initial video production with three medical personnel associated with the research team. After watching the video, an in-depth interview was conducted lasting approximately 45 minutes. Field notes were recorded by the interviewer.

Data analysis

An initial coding tree using broad codes was developed by the principal investigator with the information divided into major sections addressed by the PMT constructs and the PACE communication system. Focus group transcripts were examined within each major section of the focus group guide. Two research team members read transcripts of the focus groups, and themes were identified and refined after reviewing differences and reaching a consensus. After using the revised coding tree, coding was compared, differences reconciled, and quotations were selected to illustrate the various issues that emerged from each major theme.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Three focus groups were conducted prior to the development of the educational video with a total of 15 patients. Two focus groups were conducted with women (n=11) and one group was conducted with men (n=4). Eight participants (53%) identified themselves as African American or Black, six (40%) as White, and one as Native American. The mean age of the participants was 64 years, with an age range of 50–84 years. Sixty-seven percent of the participants reported having had a CRC screening test in the past, although several were not within recommended screening guidelines. Following the production of the educational video, two focus groups were conducted with nine of the original participants to determine if their concerns and suggestions discussed in the initial groups were accurately included in the educational video.

Two African American physicians (one female and one male) and a White male nurse viewed the video for accuracy and suggested ways to improve the delivery of the medical information.

PMT Themes

Threat Appraisal

Intrinsic and extrinsic rewards

Patients’ comments regarding reasons to complete CRC screening versus not completing screening focused on having a better quality of life if the disease was diagnosed at an earlier stage. Another important reason for completing CRC screening was to maintain good health in order to take care of their families.

“…but if it saves my life, I have too many people in my family that need me.”

In addition, individuals expressed that their family members supported and approved of them completing CRC screening.

Vulnerability and severity

The seriousness of colon cancer was recognized and acknowledged by all focus group participants. Their perceived risk of being diagnosed with colon cancer, however, varied depending on their knowledge of someone with a history of colon cancer, and/or their ability to blunt their concerns. For example, one participant who had a sister diagnosed with CRC stated:

“No I don’t feel that I am going to…I know I should think that you know, that it is a possibility of me catching it you know, getting cancer, but it is not something that I am dwelling on.”

CRC Fear

Several participants expressed that the fear of cancer was a barrier to completing a colon cancer screening test. This theme emerged in all groups and the discussion focused on procedural concerns and/or concerns associated with the diagnosis of cancer. The following comment is typical of the discussion around the concept of fear of the test procedures.

“Because a lot of times you have a fear because you don’t know what’s going to happen and just the idea of having a test for cancer or whatever, it puts a fear in you. But if you have an idea of what’s going on and how it would be done then it takes that fear out.”

Additionally, several participants commented on their fear of being diagnosed with any type of cancer. This was a common issue raised by members of each focus group and was expressed by one participant the following way: “I think just the word cancer…that is where the fear is.”

Sources of information

Environmental and Intrapersonal

The types of environmental sources of CRC screening information mentioned by the participants were brochures and posters in the health center waiting room and examination rooms, articles in popular magazines, and CRC screening commercials that have recently been broadcasted on television.

Although none of the participants had a personal history of CRC, there were a few individuals who had friends and family members who had been diagnosed with CRC. Personally knowing someone with CRC or colon polyps provided several participants with some information about CRC and CRC screening; however the accuracy of the information varied among participants.

Response-efficacy and self-efficacy

Participants spent considerable time discussing the response efficacy (CRC screening is effective) of completing CRC screening and the self-efficacy (confidence in the ability to complete the CRC screening test) of completing a CRC screening test. Many of the response efficacy comments focused on the message that cancer screening detects the disease in its early stages when there is a better chance of fighting the disease. One participant’s comments addressed this point of view.

“That is the thing that you catch on all messages now is you know preventive…the earlier you catch it…the earlier detection is really the key to fighting any cancer….is trying to catch it as soon as possible.”

The self-efficacy component of completing the different CRC screening tests was addressed by several of the participants in each focus group. Participants had differences of opinion about the screening tests. For example, a few participants expressed their aversion to handling their fecal matter to complete the FOBT. Other participants in the same groups expressed that the FOBT was easy to complete and explained the technique to others in the group.

“You don’t have to touch it with anything but just the stick. You don’t have to have your hands about it.”

Response cost

The participants had many comments that focused on the response cost associated with completing a CRC screening test. One theme that emerged addressed the embarrassment that some individuals have with completing a CRC screening test. One participant noted the embarrassment of completing a FOBT and having to return cards to the clinic with fecal material smeared on them.

“Now they give it to you where you can mail it back in and I am thinking, Oh, God. The postal people are going to get this stuff!”

Participants in the focus group suggested messages for people who were concerned about being embarrassed or not having enough time to complete a CRC screening test. To deal with the embarrassment issue, one participant stated:

“You have probably been through a lot of embarrassing things in your life that didn’t save your life, but this could save your life.”

Another participant suggested the following message for individuals concerned about the time associated with completing a FOBT.

“I think that people can take…say how many minutes do they talk on the phone a day? If they could take one minute each day to do that, I don’t know what the problem is.”

System level issues

Discussion about when to show the educational video to future patients brought up a significant system level barrier perceived by participants in each of the focus groups. Some participants expressed concern that the waiting time at the health centers could be a deterrent to participation in a formal educational program before their appointment, while others suggested that the best way to inform patients would be to have the video playing in the waiting room.

Themes Reflecting Communication Issues

One-third of the participants had never completed a CRC screening test and reported that their healthcare providers never discussed the topic with them.

“All of the doctors I have been to have never mentioned it to me.”

One participant stated that the doctor never told her to complete a CRC screening test, so she finally asked her doctor for the screening test.

“Yeah, because nobody had…and I go to numerous doctors and nobody had ever mentioned it and I said, ‘I think that I am well over fifty that I should have this done’.”

Several participants mentioned the limited time their doctors spent with them as a possible barrier to recommending CRC screening.

“Sometimes doctors just listen to the symptoms you have at the moment instead of trying to follow up. They just treat your immediate symptoms.”

In response to the limited time spent with their doctors, several participants suggested that if patients came prepared to their medical visits, that it might help in facilitating recommendations for CRC screening.

“I think that writing down some of your questions before you go. I read that somewhere and I thought it was a pretty good idea if you write down what you want to ask them.”

In addition to being prepared for the medical visit, the concept of asking the doctor for a CRC screening test was discussed. Participants did not express any reluctance to bringing up the topic of CRC screening with their providers.

“Like go in and ask him for a test? I wouldn’t have a problem with that.”

Important Suggestions

Many suggestions made by the participants about CRC and CRC screening were foreseen. However, three important ideas were strongly suggested by the participants during the focus groups. The first significant suggestion was that the video should specifically demonstrate how to complete the FOBT. In addition to the video, participants suggested that patients should be provided with understandable instructions to take home as a reminder of how to complete the FOBT. Participants expressed a fear of completing the FOBT incorrectly even though the participants stated that their providers explained the test to them and provided them with written instructions.

The second idea made by the participants was to include a provider in the video providing facts about CRC as a method to provide a respected and authoritative voice to the video.

The third suggestion made by the participants was that only one video needed to be made if it contained a balanced representation of both men and women as well as individuals of different ethnicities and races. Not one focus group participant expressed that the educational video had to be gender or race specific, even after probing for that specific information.

Educational Video Filming and Review

At the conclusion of the initial patient focus groups, a film production company was identified and several meetings occurred to determine the best strategies to reach the objectives of the video production. Several tasks were identified and completed prior to beginning the filming of the video. Examples of tasks were: the script was drafted and revised several times for clarity and consistency of language, graphics were developed, video footage of the FOBT being completed was obtained, physicians agreed and consented to participate in the video, and actors were hired for the narrative sections of the video. Filming of the physicians (an African American female and a White male) and one African American male actor was conducted at the health center. Additional filming of the actors (an African American male and female and a White male and female), voice over recordings and film editing were conducted at the production studio. The completed CRC screening educational video was 13 minutes in duration.

The content of the video focused on the PMT constructs. First, the threat appraisal of CRC (severity, vulnerability) was increased by providing facts about CRC (e.g. risk factors, incidence and mortality rates). Next, coping appraisal was increased by providing information about the importance of CRC screening (e.g. early diagnosis, importance of being there for your family) and the accurate completion of the FOBT (e.g. instructions on how to complete the test, the importance of annual completion of the test, and follow-up of a positive test). This section of the video included: physicians explaining the importance of completing a FOBT, graphics demonstrating the location of the colon, and footage of the FOBT being completed. This was followed by a narrative section that focused on talking to your doctor about CRC screening by using the concepts included in the PACE communication system. At the end of the video, patient testimonials were used to reinforce the importance of completing the FOBT.

Post Production Assessment

Post production review of the video was conducted by focus group participants and medical personnel to check for clarity of the information, cultural appropriateness of the video content, and medical accuracy. The focus group participants stated that the video captured their suggestions and expressed satisfaction with the video. The participants thought the video kept their interest and was easy to understand. In addition, the words and graphics were not difficult to read, the voice over was easy to understand, and the narrative section worked well to convince people to ask their doctor for a CRC screening test.

“And he let him know, you know, you are my friend and you’re a certain age and you need to think about it. Talk to your doctor, see what your doctor tells you, don’t, just don’t listen to me.”

The video included a male and female doctor who provided information about CRC and CRC screening. Several of the participants assumed that the female doctor was a nurse; therefore a graphic with the names of the providers was added near the bottom of the monitor.

Prior to the review of the educational video, the medical personnel were asked to pay specific attention to the medical accuracy and the cultural competency of the video and to document any errors. In addition, the physicians and nurse were encouraged to make any suggestions on ways to improve the content and/or the quality of the video. The physicians and nurses took notes while reviewing the video and then a discussion occurred focusing on the video content and quality. Several times during this process the video was replayed to focus on a certain segment of the video that was being discussed. Several suggestions on ways to improve the delivery of the medical content in the video were made by the medical personnel. For example, the physicians suggested adding information to the FOBT instruction section directing the patient to call their doctor’s office immediately if they see blood in their stool. In addition, one physician suggested that colon cancer prevention tips (healthy eating, increasing exercising, smoking cessation) should also be included in the video so a new section was added to the video during final production. All suggestions made by the physicians and the nurse regarding ways to improve the medical content of the video were included in the final editing of the video.

DISCUSSION

Compliance with CRC screening recommendations is poor among average-risk adults. Reasons for the low use of CRC screening tests include patient, provider, and system level barriers.9–21 Patient level barriers to CRC screening include many factors, but two significant issues are the lack of knowledge about CRC screening and/or lack of physician recommendation for a CRC screening test. To address these patient level barriers to CRC screening, we used a patient-level approach to develop CRC educational materials that will be used in a subsequent randomized controlled trial. Barriers mentioned in the focus group discussions for this study were consistent with previous studies and also suggested by the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT).9–21 Participants in this study, however, were adamant about including three important suggestions in the CRC screening educational video.

The first suggestion was to include actual footage demonstrating how to complete the FOBT. This recommendation suggested that patients need more detailed instructions than are currently being supplied by the commercially available FOBT kits or by healthcare providers’ verbal explanations. In many medical practices, the FOBT kits may be given out during the patient visit; formal instructions may not be provided or may be written at a level that is not understood by patients. Inclusion in the video of footage demonstrating how to complete the FOBT provides patients with the needed information to increase their self-efficacy, and thus may improve patient compliance with completing this specific CRC screening test. The participants in this study found this section of the video helpful and did not think it was too graphic. To further increase FOBT self-efficacy, as was suggested by the study participants, a low literacy FOBT instruction brochure (Flesch-Kincaid grade level =6) was developed for patients whose healthcare providers recommended a FOBT. Since inadequate health literacy has been identified as a barrier to CRC screening test completion in previous studies,10, 23, 28, 34–36 it is our belief that a combination of the FOBT demonstration in the video in conjunction with the developed low literacy FOBT test instructions will significantly reduce this barrier for patients.

The second suggestion by the participants was to include the authoritative voice of a physician. A physician recommendation or discussion about CRC screening has been shown to be a significant motivator for patients to complete CRC screening tests within recommended guidelines.10, 23, 36 It was not originally planned to have a physician featured in this video since multiple providers practice at this one health center. This patient suggestion identified and confirmed the importance of a physician recommendation for CRC screening completion even if the physician making the recommendation is not the patient’s doctor.

The final suggestion by the participants was that only one video needed to be produced if the video included a balanced representation of men and women of different races. This suggestion was echoed by participants in all focus groups and has significant cost savings implications, as well as potentially simplifying logistic issues in a busy medical center. Because of this suggestion, great care was taken to include male and female patients of different races as well as male and female doctors of different races in the video. Race matched and sex matched interventions have been shown to be important in other behavioral interventions to increase cancer screening rates,37–39 but cultural matching has not been supported in all prevention research.40 Participants in this study thought that the video was well balanced and should be fully accepted by all individuals. Members of one focus group, however, did suggest the importance of producing a Spanish version of the educational video if it demonstrates value by increasing CRC screening rates in the clinical trial.

Existing literature about patient communication skills training supports its value in improving patients’ participation in medical interviews, recall of treatment information and recommendations, and patient outcomes.27, 33, 41, 42 By using an educational video to activate patients to ask their doctor about CRC screening in addition to providing CRC and CRC screening information, we believe that provider-patient discussion about CRC screening will occur and more CRC screening will be completed.

Previous behavioral interventions to improve CRC screening directed at the patient have had some success in increasing CRC screening rates by approximately 10–20%.17, 43, 44 The behavioral intervention developed in this study is directed at the patient level; however, it uniquely focuses on both increasing CRC screening knowledge and facilitating patient-provider communication about CRC screening. Modeling communication skills such as question-asking and expressing concerns may influence patients’ perceived self-efficacy in communicating with physicians about CRC screening. This aspect of the intervention may best be accomplished by using a narrative form of communication (storytelling, testimonials, etc.) which has shown promise as an important strategy in cancer prevention and control.45 Activating patients to communicate with their providers about CRC screening may be an important step to increasing CRC screening rates and decreasing CRC disparities.

Our study does have limitations. This was a formative study and the number of participants was relatively small and may not reflect views of all low-income patients attending federally funded health centers. Despite the small number of participants, each focus group emphasized the same important issues and concerns associated with completing CRC screening. Individual responses in the focus groups might have been influenced by the group discussion or by a participant who dominated the conversation. This was minimized by using a skilled focus group moderator. Some participants may have had a different perspective because they had a friend or family member diagnosed with colon cancer or they had completed a CRC screening test in the past. Although this may have influenced the focus group discussion, capturing facilitators to complete CRC screening is also important in the development of educational materials. It was important to confirm that the participants’ suggestions in the initial focus groups were captured in the developed video, so the same participants were asked to participate in the second focus groups to provide initial feedback of the video.

TRANSLATION TO HEALTH EDUCATION PRACTICE

The issues raised by the participants (patients and healthcare providers) in this formative research provided valuable information in the development of an educational video to improve patient knowledge and patient-provider communication about CRC screening. It is thought that the educational video developed by the information obtained in this study is more likely to be effective in increasing CRC screening rates because the concerns of community members were addressed, their suggestions were incorporated in the educational video, and their review of the video documented that the message was important, understandable, influential, and delivered in a culturally appropriate method.

Educational materials that empower or activate the patient may potentially have a significant impact on increasing CRC screening rates. Since inadequate health literacy may be a potential problem, a patient educational video was developed to improve CRC and CRC screening knowledge and patient-provider communication about CRC screening among a low-income population.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures, 2007. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-Update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pignone M, Rich M, Teutsch SM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer in adults at average risk: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:132–141. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-2-200207160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer screening in the United States, 2007: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:90–104. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu KC, Tarone RE, Chow WH, et al. Temporal patterns in colorectal cancer incidence, survival, and mortality from 1950 through 1990. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:997–1006. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.13.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) [Accessed November 10,2008];Colorectal Cancer Screening. 2006 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/

- 8.American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts and Figures Special Edition 2005. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller DP, Jr, Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, et al. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klabunde CN, Schenck AP, Davis WW. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Medicare consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meissner HI, Breen N, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:389–394. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashford A, Gemson D, Sheinfeld Gorin SN, et al. Cancer screening and prevention practices of inner-city physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:59–62. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy BT, Nordin T, Sinift S, et al. Why hasn't this patient been screened for colon cancer? An Iowa Research Network study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:458–468. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.05.070058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes-Rovner M, Williams GA, Hoppough S, et al. Colorectal cancer screening barriers in persons with low income. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:240–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, et al. A national survey of primary care physicians' colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med. 2003;36:352–362. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(02)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy BD, Moskowitz MA. Screening flexible sigmoidoscopy: patient attitudes and compliance. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:120–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02599753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernon SW. Participation in colorectal cancer screening: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1406–1422. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.19.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramanian S, Klosterman M, Amonkar MM, et al. Adherence with colorectal cancer screening guidelines: a review. Prev Med. 2004;38:536–550. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dulai GS, Farmer MM, Ganz PA, et al. Primary care provider perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in a managed care setting. Cancer. 2004;100:1843–1852. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klabunde CN, Vernon SW, Nadel MR, et al. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a comparison of reports from primary care physicians and average-risk adults. Med Care. 2005;43:939–944. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000173599.67470.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O'Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, et al. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med. 2004;39:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greisinger A, Hawley ST, Bettencourt JL, et al. Primary care patients' understanding of colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paskett ED, Rushing J, D'Agostino R, Jr, et al. Cancer screening behaviors of low-income women: the impact of race. Womens Health. 1997;3:203–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz ML, James AS, Pignone MP, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African American church members: a qualitative and quantitative study of patient-provider communication. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, et al. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:635–641. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.4.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Physician-patient communication about colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1493–1499. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0289-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cegala DJ, Marinelli T, Post D. The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:57–64. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis TC, Dolan NC, Ferreira MR, et al. The role of inadequate health literacy skills in colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Invest. 2001;19:193–200. doi: 10.1081/cnv-100000154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis TC, Berkel HJ, Arnold CL, et al. Intervention to increase mammography utilization in a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:230–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yancey AK, Tanjasiri SP, Klein M, et al. Increased cancer screening behavior in women of color by culturally sensitive video exposure. Prev Med. 1995;24:142–148. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogers RW P-DS. Protection Motivation Theory. 1 vol. New York: Plenum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cegala DJ, Lenzmeier Broz S. Physician communication skills training: a review of theoretical backgrounds, objectives and skills. Med Educ. 2002;36:1004–1016. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cegala DJ, McClure L, Marinelli TM, et al. The effects of communication skills training on patients' participation during medical interviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;41:209–222. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meade CD, McKinney WP, Barnas GP. Educating patients with limited literacy skills: the effectiveness of printed and videotaped materials about colon cancer. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:119–121. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meade CD. Producing videotapes for cancer education: methods and examples. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:837–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz ML, Tatum C, Dickinson SL, et al. Improving colorectal cancer screening by using community volunteers : results of the Carolinas cancer education and screening (CARES) project. Cancer. 2007;110:1602–1610. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pasick RJ, Hiatt RA, Paskett ED. Lessons learned from community-based cancer screening intervention research. Cancer. 2004;101:1146–1164. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, et al. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kreuter MW, Skinner CS, Steger-May K, et al. Responses to behaviorally vs culturally tailored cancer communication among African American women. Am J Health Behav. 2004;28:195–207. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, et al. Culturally grounded substance use prevention: an evaluation of the keepin' it R.E.A.L. curriculum. Prev Sci. 2003;4:233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cegala DJ. Patient communication skills training: a review with implications for cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:91–94. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00087-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michie S, Miles J, Weinman J. Patient-centredness in chronic illness: what is it and does it matter? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:761–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myers RE, Ross EA, Wolf TA, et al. Behavioral interventions to increase adherence in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 1991;29:1039–1050. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199110000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreuter MW, Green MC, Cappella JN, et al. Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:221–235. doi: 10.1007/BF02879904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]