Abstract

Bacillus anthracis vaccine candidate: Sera of rabbits exposed to live and irradiated-killed spores of B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 or immunized with B. anthracis polysaccharide conjugated to KLH elicited antibodies that recognize isolated polysaccharide and two synthetic trisaccharides providing a proof-of-concept step in the development of vegetative and spore-specific reagents for detection and targeting of non-protein structures of B. anthracis.

Keywords: Bacillus anthracis, glycoconjugate, oligosaccharide, vaccine, protein conjugation

B. anthracis is a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium that causes anthrax in humans and other mammals.[1, 2] The relative ease by which B. anthracis can be weaponized and the difficulty associated with the early recognition of inhalation anthrax due to the non-specific nature of its symptoms were underscored by the deaths of five people who inhaled spores from contaminated mail.[3–5] As a result, there is a renewed interest in anthrax vaccines and early disease diagnostics.[6]

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed (AVA; BioThrax®, Emergent BioSolutions Inc.) is currently the only licensed anthrax vaccine in the US.[7, 8] The principal immunogen of AVA is anthrax toxin protective antigen (PA). Antibody responses against PA target and block the toxemia that is a necessary prerequisite of vegetative cell growth and bacteremia. Vaccines comprising additional B. anthracis specific antigens have been proposed as improvements to PA-only formulations as they have potential to target inclusively the toxemia and the vegetative cell or infectious spore.[9–11] Recently described polysaccharides and glycoproteins of B. anthracis offer exciting new targets for these vaccine formulations and also for the development of improved diagnostics for B. anthracis. For example, an unusual oligosaccharide derived from the collagen-like glycoprotein Bc1A of the exosporium of B. anthracis has been characterized,[12] chemically synthesized,[13–18] and immunologically evaluated. The latter studies demonstrated that the oligosaccharide is exposed to the immune system[14] and has an ability to elicit relevant antibodies.[13]

Recently, we reported the structure of a unique polysaccharide released from the vegetative cell wall of B. anthracis, which contains a →6)-α-d-GlcNAc-(1→4)-β-d-ManNAc-(1→4)-β-d-GlcNAc-(1→) backbone and is branched at C-3 and C-4 of α-d-GlcNAc with α-d-Gal and β-d-Gal residues, respectively and the β-GlcNAc substituted with 〈-Gal at C-3 (Scheme 1).[19, 20] These positions are, however, only partially substituted leading to micro-heterogeneity.

Scheme 1.

Structure of the secondary cell wall polysaccharide of B. anthracis and synthetic compounds 1 and 2.

As part of a project to determine antigenic determinates of the polysaccharide of B. anthracis and to establish it as a diagnostic or vaccine candidate, we report here the chemical synthesis and immunological properties of trisaccharides 1 and 2 (Scheme 1). These compounds, which are derived from B. anthracis polysaccharide, contain a 5-aminopentyl spacer for selective conjugation to carrier proteins required for enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA). It has been found that sera of rabbits exposed to live and irradiated-killed spores of B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 or immunized with polysaccharide conjugated to KLH recognize the isolated polysaccharide and the synthetic compounds 1 and 2. The data provide a proof-of-concept step in the development of vegetative and spore-specific reagents for detection and targeting of non-protein structures of B. anthracis.

Compound 1 was conveniently prepared from monosaccharide building blocks 3,[21] 4, and 7.[22] Thus, a NIS/TMSOTf mediated glycosylation[23] of thioglycoside 3 with the C-4 hydroxyl of glycosyl acceptor 4 gave disaccharide 5 in a yield of 87% as only the β-anomer (Scheme 2). Interestingly, a lower yield of disaccharide was obtained when a glycosyl acceptor was employed that had a benzyloxycarbonyl-3-aminopropyl instead of a N-Benzyl-N-benzyloxycarbonyl-5-aminopropyl spacer.[24] Next, the 2-naphthylmethyl ether[25, 26] of 5 was removed by oxidation with DDQ in a mixture of dichloromethane and water to give glycosyl acceptor 6, which was used in a TMSOTf mediated glycosylation with (N-phenyl)trifluoracetimidate 7[27–29] to afford trisaccharide 8 in an excellent yield as only the α-anomer. The use of a conventional trichloroacetimidate as glycosyl donor[30] led to a lower yield of product due to partial rearrangement to the corresponding anomeric amide. Target compound 1 was obtained by a three-step deprotection procedure involving reduction of the azide to an acetamido moiety by treatment with Zn/CuSO4[31] in a mixture of acetic anhydride, acetic acid, and THF, followed by saponification of the acetyl ester and reductive removal of benzyl ethers and benzyloxycarbamate by catalytic hydrogenation over Pd.

Scheme 2.

Reagents and conditions. a) NIS/TMSOTf, DCM 0 °C; b) DDQ, DCM, H2O; c) TMSOTf, DCM, Et2O, 50 °C; d) Zn/CuSO4, AcOH, Ac2O, THF; e) NaOMe, MeOH then Pd(OH)2/C, H2, AcOH, t-BuOH, H2O; f) NaOMe, MeOH; g) Tf2O, pyridine, DCM, 0 °C; h) NaN3, DMF, 50 °C; i) PMe3, THF, H2O then Ac2O, pyridine; j) Pd(OH)2/C, H2, AcOH, t-BuOH, H2O.

A challenging aspect of the preparation of target compound 2 is the installment of a β-mannosamine moiety.[27] A strategy was adopted whereby a β-glucoside is initially installed using a glucosyl donor having a participating ester protecting group at C-2 to control beta-anomeric selectivity.[32] Next, the C-2 protecting group can be removed and the resulting hydroxyl triflated which can then be displaced by an azide to give a 2-azido-β-d-mannoside. Another strategic aspect of the synthesis of 2 was the use of an acetyl ester and 2-naphtylmethyl ether[25, 26] as a set of orthogonal protecting groups, which makes it possible to selectively modify C-2’ of the β-glucoside and install an α-galactoside at C-3 of 2-azido-glucoside moiety. Thus, a NIS/TMSOTf mediated glycosylation[23] of thioglycoside 10[33] with 11 gave disaccharide 12 in an excellent yield as only the β-anomer. The acetyl ester of 12 was saponified by treatment with sodium methoxide in methanol to give 13. Next, the alcohol of 13 was triflated by treatment with triflic anhydride in a mixture of pyridine and dichloromethane to afford triflate 14, which was immediately displaced with sodium azide in DMF at 50 °C to give mannoside 15. The 2-naphthylmethyl ether of 15 was removed by oxidation with DDQ[26] and the resulting glycosyl acceptor 16 was glycosylated with 7 in the presence of a catalytic amount of TMSOTf in a mixture of dichloromethane and diethyl ether to give anomerically pure trisaccharide 17. Deprotection of 17 was accomplished by reduction of the azides with trimethyl phosphine[34] followed by acetylation of the resulting amine with acetic anhydride in pyridine and then reductive removal of the benzyl ethers and benzyloxycarbamate by catalytic hydrogenation over Pd to give compound 2.

For immunological evaluations, trisaccharides 1 and 2 were conjugated to BSA by reaction with S-acetylthioglycolic acid pentafluorophenyl ester to afford the corresponding thioacetate derivatives, which after purification by size-exclusion chromatography were de-S-acetylated using 7% ammonia (g) in DMF and conjugated to maleimide activated BSA (BSA-MI, Pierce Endogen, Inc.) in a phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). After purification using a centrifugal filter device with a nominal molecular weight cut-off of 10 KDa, neoglycoproteins were obtained with an average of eleven and nineteen molecules of 1 and 2, respectively per BSA molecule as determined by Bradford’s protein assay and quantitative carbohydrate analysis by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD).

Next, conjugates of KLH and BSA to the polysaccharide of B. anthracis were prepared for immunizing rabbits and to examine anti-sera for anti-polysaccharide antibodies, respectively. To this end, the polysaccharide was treated with 1-cyano-4-dimethylaminopyridinium tetrafluoroborate (CDAP)[35] to form reactive cyanyl esters, which were condensed with free amines of BSA and KLH to give, after rearrangement of isourea-type intermediate, carbamate-linked polysaccharides. The KLH- and BSA-polysaccharide conjugate solutions were purified using centrifugal filter devices (Micron YM 30,000 Da) and then lyophilized. Saccharide loadings of 0.3 mg/mg BSA and 0.96 mg/mg KLH were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA; BSA-conjugate) and Bradford’s (KLH-conjugate) protein assay and quantitative carbohydrate analysis by HPAEC-PAD. In addition, maltoheptaose was conjugated to BSA using CDAP to obtain a control conjugate to examine for the possible presence of anti-linker antibodies.[36]

Rabbits were inoculated intramuscularly four times at bi-weekly intervals with live- or irradiated spores (3 × 106 total spores),[14] or polysaccharide-KLH conjugate followed by the collection of terminal bleeds fourteen days after the last immunization. ELISA was used to examine the pre- and post-immune sera for polysaccharide recognition. Thus, microtiter plates were coated with the polysaccharide-BSA conjugate and serial dilutions of sera added. An anti-rabbit IgG antibody labeled with horseradish peroxidase was employed as a secondary antibody for detection purposes. High titers of anti-polysaccharide IgG antibodies had been elicited by the polysaccharide-KLH conjugate (Figure 1A and Table 1). Furthermore, inoculation with live and irradiated spores resulted in the production of IgG antibodies that can recognize the polysaccharide. Antisera obtained from immunizations with polysaccharide-KLH conjugate showed recognition of maltoheptaose linked to BSA albeit at much lower titers than when polysaccharide linked to BSA was used as ELISA coating. This finding indicates that some anti-linker antibodies had been elicited.[36] As expected, antisera from rabbits immunized with live and irradiated spores showed no reactivity towards the maltoheptaose conjugate (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Immunoreactivity of polysaccharide and trisaccharides 1, and 2 to antisera elicited by B. anthracis Sterne live spores, irradiated-killed spores, and polysaccharide-KLH conjugate. Microtiter plates were coated with polysaccharide-BSA (A), maltoheptaose-BSA (B), 1-BSA (C), and 2-BSA (D) conjugates (0.15 µg mL−1 carbohydrate). Serial dilutions of rabbit anti-live and anti-irradiated B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 spores antisera and rabbit anti-polysaccharide-KLH antiserum (starting dilution 1:200) were applied to coated microtiter plates. Serial dilutions of the pre-immune sera of the rabbits (starting dilution 1:200) did not show any binding to polysaccharide-BSA (data not shown). Wells only coated with BSA at the corresponding protein concentration did not show binding to any sera (data not shown). The optical density (OD) values are reported as the means ± SD of triplicate measurements.

Table 1.

ELISA antibody titers after immunization with B. anthracis Sterne live spores, irradiated-killed spores, and polysacchride-KLH.

| Immunization | live spores | irradiated spores | polysaccharide-KLH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating | |||

| polysaccharide-BSA | 18,500 | 6,100 | 239,700 |

| maltoheptaose-BSA | 0 | 0 | 3,600 |

| 1-BSA | 400 | 6,800 | 57,300 |

| 2-BSA | 18,700 | 2,600 | 46,700 |

ELISA plates were coated with BSA conjugates (0.15 µg mL−1 carbohydrate) and titers determined by linear regression analysis, plotting dilution versus absorbance. Titers are defined as the highest dilution yielding an optical density of 0.5 or greater.

Next, the specificity of the anti-polysaccharide antibodies was investigated using synthetic trisaccharides 1 and 2 (Scheme 1) linked to BSA. Trisaccharides 1 and 2 were equally well recognized by IgG antibodies elicited by the polysaccharide-KLH conjugate and irradiated-killed spores (Figures 1C, D and Table 1). Surprisingly, antisera obtained after inoculation with live spores recognized trisaccharide 2 much better than trisaccharide 1.

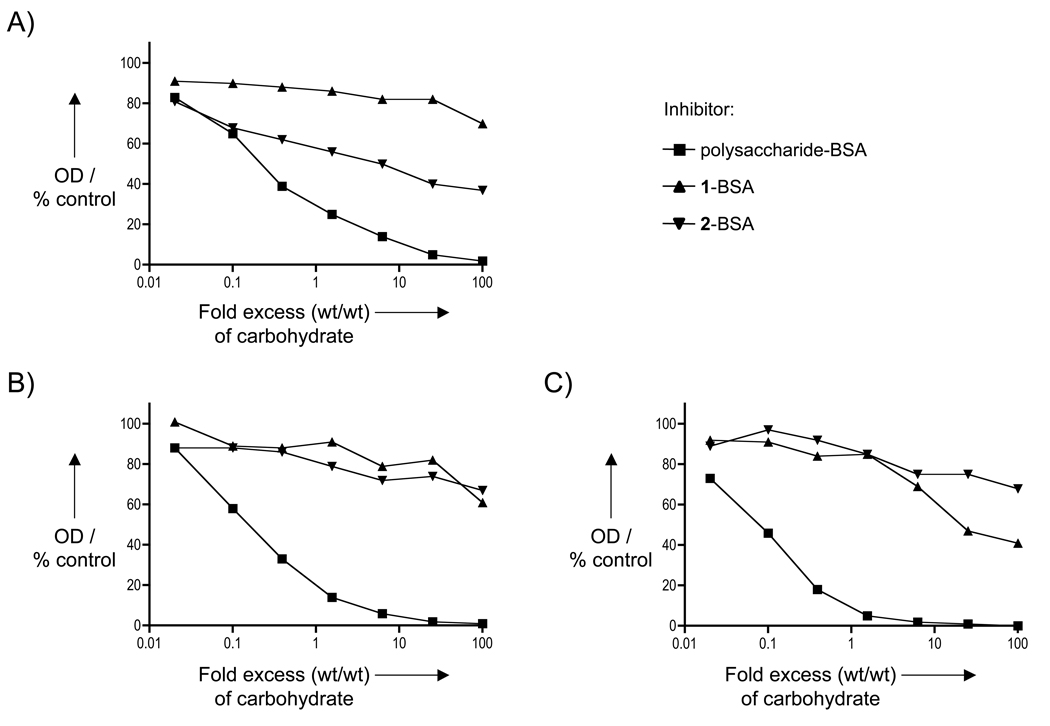

To further study the antigenic components of the various antisera, inhibition ELISAs were performed by coating microtiters plates with polysaccharide-BSA conjugate and using 1-BSA, 2-BSA, and polysaccharide-BSA as inhibitors (Figure 2). As expected, for each anti-serum, the polysaccharide-BSA inhibitor could completely block the binding of IgG antibodies to immobilized polysaccharide, whereas only partial inhibition was observed for 1-BSA and 2-BSA. Furthermore, antibodies elicited by the live spore vaccine recognized trisaccharide 2 much better than 1, whereas the KLH-polysaccharide antiserum was better inhibited by 1. Antibodies elicited by the irradiated spore inoculum recognized 1 and 2 equally well. The partial inhibition by the synthetic compounds indicates that heterogeneous populations of antibodies have been elicited. Furthermore, the difference in antigenic component of the vaccines may be due to differences in presentation of the polysaccharide when part of vegetative cells, or attached to KLH, or when part of irradiated-killed spores.

Figure 2.

Competitive inhibition ELISA. Microtiter plates were coated with polysaccharide-BSA conjugate (0.15 µg mL−1 carbohydrate). Dilutions of rabbit anti-live (A) and anti-irradiated (B) B. anthracis Sterne 34F2 spores antisera and rabbit anti-polysaccharide-KLH antiserum (C) mixed with polysaccharide-BSA, 1-BSA, and 2-BSA (0–100-fold excess, wt/wt based on carbohydrate concentration) were applied to coated microtiter plates. Maltoheptaose-BSA conjugate and unconjugated BSA at corresponding concentrations mixed with antisera did not display inhibition (data not shown). OD values were normalized for the OD values obtained in the absence of inhibitor (0-fold “excess”, 100%).

The results presented here show that both live- and irradiated-killed B. anthracis spore inoculae and polysaccharide linked to the carrier protein KLH can elicit IgG antibodies that recognize isolated polysaccharide and the relatively small saccharides 1 and 2. Previously, the polysaccharide was identified as a component of the vegetative cell wall of B. anthracis, and thus, it was surprising that irradiated-killed spores could elicit anti-polysaccharide antibodies. It appears that not only vegetative cells but also B. anthracis spores express the polysaccharide. The implication of this finding is that a polysaccharide-based vaccine may provide immunity towards vegetative cells as well as spores. In this respect, we hypothesize that immune responses to dormant B. anthracis spores at the mucosal surface may inhibit spore uptake across the mucosa and may also target the susceptible emergent vegetative cell, thus preventing bacterial proliferation or enhancing bacterial clearance. Highly conserved integral carbohydrate components of the spore and vegetative cell structure are attractive vaccine candidate antigens because, unlike capsules, they are not sloughed off the replicating cell. Finally, we have located important antigenic components of the various antisera using synthetic saccharides.

The data provide an important proof-of-concept step in the development of vegetative and spore-specific reagents for detection and targeting of non-protein structures in B. anthracis. These structures may in turn provide a platform for directing immune responses to spore structures during the early stages of the B. anthracis infection process. Ongoing studies will demonstrate whether anti-polysaccharide antibodies can recognize B. anthracis spores including the highly virulent B. anthracis Ames and B. anthracis cured of virulence plasmids (pXO1 and pXO2). Examination of the cross reactivity of the antisera with cell wall polysaccharides from various Bacillus species and determination of antigenic responses against the synthetic oligosaccharides are also underway.[37]

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Institute of General Medicine of the National Institutes of Health, grant GM065248 (GJB) and NIAID, grant AI059577 (RWC). We wish to thank Dr. Therese Buskas for the preparation of the BSA conjugates and Dr. Elke Saile for assistance with rabbit immunizations.

References

- 1.Priest FG. In: Bacillus subtilis and Other Gram-positive Bacteria: Biochemistry, Physiology, and Molecular Biology. Sonenshein AL, Hoch JA, Losick R, editors. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mock M, Fouet A. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:647–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jernigan JA, Stephens DS, Ashford DA, Omenaca C, Topiel MS, Galbraith M, Tapper M, Fisk TL, Zaki S, Popovic T, Meyer RF, Quinn CP, Harper SA, Fridkin SK, Sejvar JJ, Shepard CW, McConnell M, Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Malecki JM, Gerberding JL, Hughes JM, Perkins BA. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2001;7:933–944. doi: 10.3201/eid0706.010604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jernigan DB, Raghunathan PL, Bell BP, Brechner R, Bresnitz EA, Butler JC, Cetron M, Cohen M, Doyle T, Fischer M, Greene C, Griffith KS, Guarner J, Hadler JL, Hayslett JA, Meyer R, Petersen LR, Phillips M, Pinner R, Popovic T, Quinn CP, Reefhuis J, Reissman D, Rosenstein N, Schuchat A, Shieh WJ, Siegal L, Swerdlow DL, Tenover FC, Traeger M, Ward JW, Weisfuse I, Wiersma S, Yeskey K, Zaki S, Ashford DA, Perkins BA, Ostroff S, Hughes J, Fleming D, Koplan JP, Gerberding JL. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2002;8:1019–1028. doi: 10.3201/eid0810.020353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb GF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:4355–4356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0830963100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouzianas DG. Expert Rev. Anti-Infective Ther. 2007;5:665–684. doi: 10.1586/14787210.5.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedlander AM, Pittman PR, Parker GW. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1999;282:2104–2106. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joellenbeck LM, Zwanziger LL, Durch JS, Strom BL. The Anthrax vaccine: is it safe? Does it work? Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneerson R, Kubler-Kielb J, Liu TY, Dai ZD, Leppla SH, Yergey A, Backlund P, Shiloach J, Majadly F, Robbins JB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8945–8950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633512100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chabot DJ, Scorpio A, Tobery SA, Little SF, Norris SL, Friedlander AM. Vaccine. 2004;23:43–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang JY, Roehrl MH. Med. Immunol. 2005;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1476-9433-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daubenspeck JM, Zeng HD, Chen P, Dong SL, Steichen CT, Krishna NR, Pritchard DG, Turnbough CL. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:30945–30953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werz DB, Seeberger PH. Angew. Chem. 2005;117:6474–6476. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502615. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 6315–6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta AS, Saile E, Zhong W, Buskas T, Carlson R, Kannenberg E, Reed Y, Quinn CP, Boons GJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:9136–9149. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crich D, Vinogradova O. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6513–6520. doi: 10.1021/jo070750s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo HB, O'Doherty GA. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:5298–5300. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5206–5208. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saksena R, Adamo R, Kovac P. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:4283–4310. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werz DB, Adibekian A, Seeberger PH. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:1976–1982. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudhury B, Leoff C, Saile E, Wilkins P, Quinn CP, Kannenberg EL, Carlson RW. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:27932–27941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leoff C, Saile E, Sue D, Wilkins P, Quinn CP, Carlson RW, Kannenberg EL. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:112–121. doi: 10.1128/JB.01292-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters T. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1991:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka H, Iwata Y, Takahashi D, Adachi M, Takahashi T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1630–1631. doi: 10.1021/ja0450298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Veeneman GH, van Leeuwen SH, van Boom JH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:1331–1334. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mong TKK, Lee HK, Duron SG, Wong CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:797–802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337590100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaunt MJ, Yu JQ, Spencer JB. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:4172–4173. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia J, Abbas SA, Locke RD, Piskorz CF, Alderfer JL, Matta KL. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:169–173. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gridley JJ, Osborn HMI. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 2000;10:1471–1491. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu B, Tao HC. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2405–2407. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu B, Tao HC. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:9099–9102. doi: 10.1021/jo026103c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt RR, Kinzy W. Advances in Carbohydrate Chemistry and Biochemistry. Vol. 50. 1994. pp. 21–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winans KA, King DS, Rao VR, Bertozzi CR. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11700–11710. doi: 10.1021/bi991247f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Classon B, Garegg PJ, Oscarson S, Tiden AK. Carbohydr. Res. 1991;216:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0008-6215(92)84161-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Misra AK, Roy N. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 1998;17:1047–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alper PB, Hendrix M, Sears P, Wong CH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:1965–1978. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafer DE, Toll B, Schuman RF, Nelson BL, Mond JJ, Lees A. Vaccine. 2000;18:1273–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00370-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buskas T, Li YH, Boons GJ. Chem. Eur. J. 2004;10:3517–3524. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.At the completion of these studies Seeberger and coworkers reported the chemical synthesis of a fragment of the B. anthracis polysaccharide. Oberli MA, Bindschadler P, Werz DB, Seeberger PH. Org. Lett. 2008;10:905–908. doi: 10.1021/ol7030262.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.