Abstract

Effects of parents' divorce on children's adjustment have been studied extensively. This article applies new advances in trajectory modeling to the problem of disentangling the effects of divorce on children's adjustment from related factors such as the child's age at the time of divorce and the child's gender. Latent change score models were used to examine trajectories of externalizing behavior problems in relation to children's experience of their parents' divorce. Participants included 356 boys and girls whose biological parents were married at kindergarten entry. The children were assessed annually through Grade 9. Mothers reported whether they had divorced or separated in each 12-month period, and teachers reported children's externalizing behavior problems each year. Girls' externalizing behavior problem trajectories were not affected by experiencing their parents' divorce, regardless of the timing of the divorce. In contrast, boys who were in elementary school when their parents divorced showed an increase in externalizing behavior problems in the year of the divorce. This increase persisted in the years following the divorce. Boys who were in middle school when their parents divorced showed an increase in externalizing behavior problems in the year of the divorce followed by a decrease to below baseline levels in the year after the divorce. This decrease persisted in the following years.

In the United States, approximately 50% of marriages end in divorce (Kreider & Fields, 2002), and 1 million children experience their parents' divorce each year (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1999). Whether and how parents' divorce affects children's adjustment is of concern to parents, clinicians, and policymakers. There is a large body of empirical research addressing these questions. Some researchers have taken extreme positions suggesting either that divorce has no measurable effects on children (Harris, 1998) or that the effects of divorce on children are quite debilitating (Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1989; Wallerstein & Kelly, 1980). However, most researchers take an intermediate position (see Cherlin, 1999).

Several methodological issues complicate the interpretation of findings to date. The most common approach to the question of whether divorce affects children's adjustment has been to compare mean levels of adjustment of children whose parents have divorced to those whose parents have not divorced. Meta-analyses of 92 studies conducted in the 1950s through 1980s (Amato & Keith, 1991) and 67 studies published in the 1990s (Amato, 2001) show that children whose parents have divorced have poorer adjustment in a number of domains than do children whose parents have not divorced. Scholars, however, have interpreted these findings in a number of ways and, as a result, have drawn disparate conclusions about how parental divorce affects children's adjustment (for a review see Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998).

Children's age at the time of their parents' divorce and children's gender have emerged as important considerations in attempts to understand how experiencing parents' divorce affects children's adjustment. Some evidence suggests, for example, that children who experience their parents' divorce as preschoolers show more long-term adjustment difficulties compared to children who are older when their parents divorce (Allison & Furstenberg, 1989; Zill, Morrison, & Coiro, 1993). Other studies suggest that experiencing parental divorce during adolescence is more deleterious than experiencing parental divorce during childhood (e.g., Chase-Lansdale, Cherlin, & Kiernan, 1995). Hetherington et al. (1998) concluded that the evidence is inconsistent and cautioned that the child's age at the time of the divorce and at the time of adjustment assessments are both important to consider in understanding how parents' divorce affects children's adjustment.

In terms of gender, some studies have found that divorce is linked to more adjustment problems for boys than for girls (Hetherington, 1989), whereas other studies have found no gender differences (Amato, 1987) or even that boys appear better adjusted than girls after their parents' divorce (Slater, Stewart, & Linn, 1983). In meta-analyses, Amato (2001) reported slightly larger effect sizes for conduct problems for boys than girls whose parents divorced, and Amato and Keith (1991) reported somewhat larger effect sizes for social relationships for boys than girls. Taken together, these findings suggest that divorce affects boys somewhat more negatively than girls.

In this article, we bring an alternative methodology to examining mean differences to disentangle the relations among divorce, children's adjustment, and related factors such as the child's age at the time of divorce and the child's gender. Specifically, we employ trajectory, or growth curve, modeling to examine children's adjustment over time. A longitudinal approach such as trajectory modeling has several advantages over cross-sectional comparisons of means. Perhaps most important, children's adjustment and trajectory at baseline can be controlled when examining their adjustment at a later point in time. For children whose parents divorce, adjustment at baseline represents how well children were functioning before the divorce; for children whose parents do not divorce, adjustment at baseline represents how well children are faring at a comparable point in time. More important, several studies have demonstrated that children whose parents eventually divorce show poorer adjustment before the divorce occurs than do children whose parents do not divorce (e.g., Block, Block, & Gjerde, 1986; Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale, & McRae, 1998; Doherty & Needle, 1991), suggesting that these children's adjustment problems cannot be explained solely by experiencing divorce and may be influenced by the family processes leading to the divorce. Controlling for initial adjustment attenuates the effects of divorce on children's later adjustment (Cherlin et al., 1991). Trajectory modeling also goes beyond merely controlling for baseline adjustment, in that the child's longitudinal trajectory—the instantaneous rate of change and, in the models presented here, rate of acceleration—are also modeled. Therefore, the impact of divorce is placed in the context of an existing, child-specific developmental process.

Although there are clear advantages conferred by adopting a longitudinal approach to understanding how divorce affects children's adjustment, several issues complicate the use of longitudinal data. Perhaps the most complex of these stems from the fact that parents divorce at different times in relation to when adjustment is measured. That is, for some children, baseline adjustment data will be collected in close temporal proximity to the time their parents divorce; whereas for other children, baseline adjustment data will be collected long prior to their parents' divorce. Prior research has not resolved the question of whether children demonstrate more adjustment problems immediately before their parents' divorce—perhaps because of conflict and other disruptions surrounding the divorce—than they do several years before the divorce. A similar issue arises in relation to the collection of data after the parents' divorce. It appears that children's adjustment problems peak immediately following parents' divorce but decrease at some point following the divorce (Chase-Lansdale & Hetherington, 1990). However, for some children in a given study, adjustment data will be collected shortly after their parents' divorce, whereas for other children, adjustment data will be collected after a longer intervening period following the divorce.

This issue is illustrated in Cherlin et al.'s (1998) seminal study that followed large, representative samples in Great Britain from the time children were 7 to 11 years old, and in the United States from the time children were between 7 and 11 years of age until they ranged in age from 11 to 16 years. Overall, the researchers found that boys and girls whose parents divorced were rated by teachers and parents as having more behavior problems both before and after the divorce than were children whose parents did not divorce, but no information about the precise timing of the divorce within the 4-year interval between times of data collection was available.

Moreover, most longitudinal data sets that have been used to examine how divorce affects children's adjustment have relatively long intervals between times of measurement (e.g., 5–6 years between the collection of Time 1 and Time 2 data in the National Survey of Families and Households; Sweet & Bumpass, 1996), which presents more limitations than if the interval between times of data collection were smaller. Despite the importance of using longitudinal data to address key questions related to divorce and children's adjustment, Karney and Bradbury (1995b) concluded in their review of 115 longitudinal studies focused on marriage that over 70% of these studies collected and analyzed only two waves of data, and studies that collected more than two waves of data typically analyzed the data points in a series of comparisons between two times. Analytic approaches common in these longitudinal studies include analysis of variance and multiple regression in which an adjustment outcome serves as the dependent variable, and divorce status and any control variables (such as Time 1 adjustment) are entered as independent variables (e.g., Amato, Loomis, & Booth, 1995; Emery, Waldron, Kitzmann, & Aaron, 1999; Videon, 2002).

Recently, growth curve modeling has emerged as an analytic tool well suited to addressing the limitations associated with the other methodological approaches described earlier (see Karney & Bradbury, 1995a). Although growth curve models have now been used to address a number of research questions using multiwave longitudinal data, they have rarely been applied to the study of how parents' divorce affects children's adjustment in relation to timing of assessment and child age at the time of the divorce. In a notable exception, Cherlin et al. (1998) presented growth curve models that specifically examined emotional problems in relation to parents' divorce for individuals who were aged 7 through 10, 11 through 15, 16 through 22, or 23 through 33 years at the time of the divorce. Their findings suggested that individuals whose parents eventually divorced had more emotional problems prior to the divorce than did individuals whose parents did not divorce, but also that divorce itself contributed to higher levels of emotional problems into adulthood. This study clearly represents an important methodological advance in the study of effects of divorce on adjustment of children, adolescents, and young adults. Nevertheless, Karney and Bradbury (1995a) cautioned that the implications of using different intervals between times of measurement are still unclear.

This study sought to address the existing methodological limitations and add to the work of Cherlin et al. (1998) by using recent advances in growth curve analysis to examine the developmental trajectories of children's externalizing behavior problems from kindergarten through Grade 8. These analyses address the questions of whether and how children's adjustment trajectories change before and after the experience of parental divorce and whether this depends on the child's age at the time of the divorce. They also make it possible to distinguish between shifts in the long-term trajectory and instantaneous increases (with follow-on effects) in adjustment problems. We selected teacher-reported externalizing behavior problems as the outcome variable because of evidence that conduct problems are an adjustment domain relatively strongly affected by divorce (Amato & Keith, 1991) and because parents' reports of children's adjustment are more likely than are teachers' reports to be biased by potential disruptions in their own adjustment preceding and following their divorce or by their expectations of disruptions in the children's adjustment.

Method

Participants

The families in this investigation were participants in an ongoing, multisite, longitudinal study of child development (see Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990; Pettit, Laird, Bates, Dodge, & Criss, 2001). Participants were recruited when the children entered kindergarten in 1987 or 1988 at three sites: Knoxville and Nashville, TN; and Bloomington, IN. Parents were approached at random during kindergarten preregistration and asked if they would participate in a longitudinal study of child development. About 15% of children at the targeted schools did not preregister. Participants in this category were recruited on the 1st day of school or by letter or telephone. Of those asked, approximately 75% agreed to participate. The sample consisted of 585 families at the first assessment; but in this study, we limited the sample to the 356 children whose biological parents were married to one another at this initial prekindergarten assessment. Boys comprised 53% of the married parents sample. Ninety percent of the sample were European American, 9% were African American, and 1% were from other ethnic groups. Families' Hollingshead (1979) socioeconomic status ranged from 11 to 66 (M = 43.78, SD = 12.44). Follow-up assessments were conducted annually through Grade 9.

Procedures and Measures

Divorce or separation

During the summer before children started kindergarten or within the first weeks of school, in-depth interviews were conducted with mothers in their homes. Information provided in these interviews was used to select the subset of children whose biological parents were married to one another when the child began kindergarten. In each subsequent year, mothers were asked whether they had divorced or separated from their spouse in the last 12 months. Consistent with most empirical studies (e.g., Amato et al., 1995; Cherlin et al., 1991; Zill et al., 1993), parental divorce and separation were not distinguished. The large majority of marital separations end in divorce within 3 years (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002); and it has been argued that in terms of child adjustment, the critical point in time is the parents' marital separation, regardless of whether this is accomplished through legal divorce (Morgan & Rindfuss, 1985). For the purposes of this study, we categorized parents as divorced–separated or not: 0 (no), 1 (yes).1

Externalizing behaviors

Children's teachers in kindergarten through Grade 8 completed the 113-item Teacher Report Form of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991; Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1986). Teachers reported whether each item was true of the child: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very or often true). The 35 items in the externalizing behavior scale (e.g., whether the adolescent gets in fights and is disobedient at school) were summed to create a measure of externalizing behavior problems in each year. Because most children had multiple teachers during the later grades, school personnel (usually the principal or school secretary) were asked to nominate the teacher most familiar with the child (usually the physical education, language arts, or homeroom teacher) to complete this measure.

Results

Sample Data

Preliminary examination of the externalizing behavior problem scores indicated substantial positive skew in many grades. A logarithmic transformation (y* = ln(y + 1)) was applied to the scores before further analysis; after transformation, most scores showed skew of an absolute value less than 1. Sample data (correlations, means, standard deviations, and proportions of missing data) after transformation for girls and boys are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. These tables, and all subsequent models, were estimated in Mplus V.2.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2002), using that software's facility for maximum likelihood estimation with missing data.

TABLE 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Female Subsample

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ext K | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Ext 1 | .39 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Ext 2 | .47 | .54 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Ext 3 | .43 | .43 | .51 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Ext 4 | .30 | .38 | .46 | .50 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Ext 5 | .27 | .32 | .40 | .47 | .52 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Ext 6 | .22 | .42 | .41 | .52 | .40 | .52 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Ext 7 | .41 | .23 | .28 | .43 | .40 | .51 | .45 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Ext 8 | .42 | .37 | .38 | .51 | .30 | .39 | .50 | .50 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 10. Af.Am. | −.08 | .09 | −.02 | .15 | .13 | .19 | .19 | .14 | .12 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 11. Div K | .02 | −.02 | −.06 | .01 | .00 | −.02 | −.07 | .00 | −.18 | .13 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 12. Div 1 | .02 | .05 | .11 | −.01 | .09 | .10 | .10 | .05 | −.09 | .05 | .61 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 13. Div 2 | .06 | .09 | −.05 | .05 | .04 | −.03 | −.01 | −.06 | .05 | .22 | .20 | .21 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 14. Div 3 | .16 | .10 | −.02 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .00 | −.08 | .14 | .18 | .12 | .19 | .65 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 15. Div 4 | .16 | −.04 | −.10 | .04 | .02 | .13 | .04 | .00 | .16 | .10 | .14 | .30 | .19 | .47 | 1.00 | |||||

| 16. Div 5 | .08 | .10 | −.03 | .02 | .06 | .02 | .06 | .02 | .16 | .05 | .24 | .18 | .08 | .40 | .38 | 1.00 | ||||

| 17. Div 6 | −.06 | .00 | −.06 | .04 | .08 | .04 | .03 | .02 | −.07 | .03 | −.06 | .01 | −.08 | .17 | .15 | .49 | 1.00 | |||

| 18. Div 7 | −.02 | .13 | .19 | .08 | .17 | .09 | .29 | −.02 | −.01 | .13 | −.10 | .08 | −.10 | .04 | .04 | .17 | .35 | 1.00 | ||

| 19. Div 8 | .06 | .18 | .18 | .11 | .16 | .13 | .34 | .04 | .03 | .15 | −.07 | .00 | −.10 | −.01 | −.09 | .10 | .28 | .87 | 1.00 | |

| 20. Div 9 | −.03 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 | .06 | .13 | .14 | −.14 | −.11 | .06 | .09 | .16 | −.06 | .13 | .09 | .07 | .12 | .33 | .24 | 1.00 |

| M | .74 | .93 | .82 | .81 | .79 | .86 | .87 | .87 | .85 | .10 | .05 | .09 | .08 | .14 | .08 | .10 | .07 | .08 | .06 | .05 |

| SD | .94 | .96 | 1.00 | .96 | .96 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.10 | .30 | .21 | .28 | .27 | .34 | .26 | .29 | .25 | .27 | .24 | .21 |

| % Missing | 2.38 | 5.36 | 11.90 | 13.69 | 14.88 | 20.24 | 20.24 | 24.40 | 25.00 | .00 | 10.12 | 17.86 | 17.86 | 24.40 | 24.40 | 14.88 | 16.67 | 23.81 | 24.40 | 21.40 |

Note. N = 168. Ext = Externalizing behavior in Grades K–8; Af.Am.—African American = 1, non-African American = 0; Div = Divorce of parents in Grades K–9.

TABLE 2.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Male Subsample

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ext K | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Ext 1 | .52 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Ext 2 | .54 | .51 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 4. Ext 3 | .60 | .51 | .50 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Ext 4 | .44 | .40 | .49 | .63 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 6. Ext 5 | .37 | .41 | .47 | .47 | .51 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 7. Ext 6 | .44 | .45 | .41 | .52 | .53 | .48 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 8. Ext 7 | .38 | .34 | .45 | .54 | .48 | .57 | .50 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 9. Ext 8 | .31 | .16 | .41 | .44 | .42 | .38 | .39 | .54 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 10. Af.Am. | .01 | .07 | .02 | .07 | .15 | .11 | .12 | .21 | −.04 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 11. Div K | .06 | .08 | .08 | .17 | .10 | .22 | .17 | .35 | .25 | .35 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 12. Div 1 | .13 | .20 | .22 | .21 | .19 | .26 | .24 | .31 | .29 | .14 | .64 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 13. Div 2 | .10 | −.07 | .02 | .07 | .19 | .11 | .08 | .15 | .05 | .17 | .12 | .18 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 14. Div 3 | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .05 | .09 | .11 | .11 | .09 | .01 | .22 | .12 | .06 | .21 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 15. Div 4 | .10 | .15 | .06 | .13 | .21 | .18 | .14 | .09 | −.04 | .00 | −.09 | −.09 | .06 | .15 | 1.00 | |||||

| 16. Div 5 | .13 | .15 | .07 | .15 | .25 | .19 | .14 | .14 | −.03 | −.03 | −.09 | −.09 | .04 | .14 | .94 | 1.00 | ||||

| 17. Div 6 | .11 | .13 | .13 | .07 | .07 | .16 | .18 | −.05 | −.05 | .04 | −.06 | .10 | .02 | −.03 | .23 | .32 | 1.00 | |||

| 18. Div 7 | .10 | .03 | .04 | .09 | .13 | .07 | .06 | .05 | −.05 | −.07 | −.03 | .04 | −.03 | −.05 | .03 | .33 | .58 | |||

| 19. Div 8 | −.11 | .02 | −.03 | −.05 | .09 | .03 | −.14 | .02 | .01 | −.05 | −.03 | .13 | −.06 | −.06 | .06 | .11 | .11 | .19 | 1.00 | |

| 20. Div 9 | −.08 | −.04 | .01 | −.03 | .06 | .07 | −.12 | −.02 | −.02 | −.03 | −.02 | −.02 | −.03 | −.05 | .05 | .10 | .09 | .29 | .80 | 1.00 |

| M | 1.27 | 1.42 | 1.43 | 1.41 | 1.47 | 1.51 | 1.51 | 1.48 | 1.51 | .07 | .05 | .08 | .04 | .05 | .06 | .07 | .06 | .08 | .04 | .03 |

| SD | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.16 | 1.17 | 1.21 | 1.14 | 1.20 | 1.09 | 1.25 | .26 | .21 | .27 | .19 | .20 | .26 | .27 | .23 | .37 | .21 | .19 |

| % Missing | 2.66 | 9.57 | 12.23 | 14.36 | 22.87 | 25.00 | 27.13 | 28.19 | 33.51 | .00 | 10.11 | 18.09 | 18.62 | 23.94 | 34.57 | 25.00 | 25.53 | 27.13 | 34.57 | 30.30 |

Note. N = 188. Ext = Externalizing behavior in Grades K–8; Af.Am.—African American = 1, non-African American = 0; Div = Divorce of parents m Grades K–9.

The entries for the means in the sample data tables indicate the proportion of the sample experiencing a divorce or separation in each year; but as remarked in Note 1, there were cases where the mother reported more than one event. Between kindergarten and Grade 9, 23% of the boys and 29% of the girls experienced at least one divorce or separation, with 12% of boys and 15% of girls experiencing more than one.

Trajectory Modeling

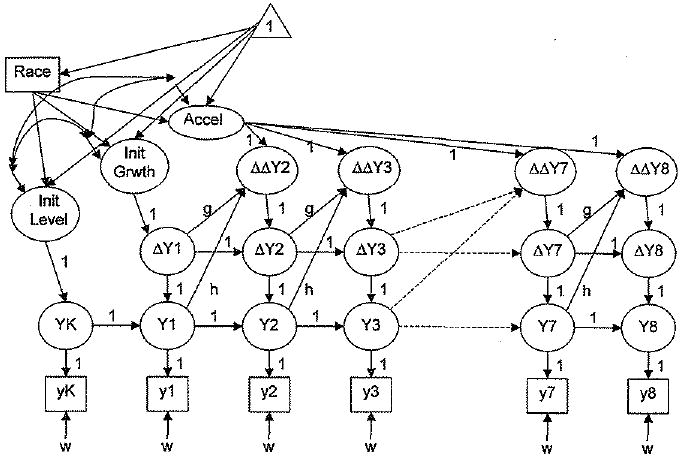

The first stage in the analysis was to construct and evaluate a latent growth model for the externalizing behavior measures. This was done in a multigroup structural equation model, allowing all parameter estimates to vary by gender. The model employed, depicted in Figure 1, was a second-order dual change score model derived from McArdle and Hamagami's (2001) work on latent difference dual change score models (the figure omits repetitive segments of the model). The core of this model is equivalent to a three-parameter latent growth model, with intercept, slope, and curvature or acceleration components (with respondent ethnicity, African American vs. non-African American, as a covariate predicting the growth parameters).

FIGURE 1.

Second-order dual change score model. Quantities with matching labels are constrained to be equal; unlabeled quantities are freely estimated. The triangle represents a constant vector.

Model description

A latent difference score can be defined directly in structural equation models (see McArdle & Nesselroade, 1994). The equation defining the latent difference in a variable Y between time t − 1 and time t can be shown as follows:

Because the equation for Yt includes no error term, and the coefficients relating Yt to Yt−1 and ΔYt are constrained to 1, Yt is directly the sum of Yt−1 and ΔYt. ΔYt can then be used as any other latent variable in an SEM. The lower three rows of variables in Figure 1 extend this simple difference score formulation across the nine time points at which externalizing behavior was measured. Note that the path arrows point to Yt from Yt−1 and ΔYt. This represents the summing operation, rather than a causal hypothesis.

The second-order model incorporates the differences of the differences (ΔΔYt in the figure). Ignoring for the moment paths g and h, the second-order change scores are equal over time and determined by the acceleration variable, which varies across individuals. Therefore, there is a constant rate of acceleration (or deceleration) for each respondent. The change between time points, ΔYt, is the sum of the previous rate of change, ΔYt−1, and the constant acceleration. The time-specific levels of Yt, then, are the sum of Yt−1 and ΔYt. In this version of the model, the capital Yt variables are the latent trajectory underlying the individual patterns of responses, which are measured with error by the manifest variables, yt.

The paths labeled g and h add a proportional change component to the growth, making this a dual change score model in McArdle and Hamagami's (2001) terminology. That is, the rate of acceleration at time t is influenced by the previous level and rate of change (the influence parameters are constant over time). Therefore, deviations at time t − 1 from the base trajectory (i.e., the trajectory that would be expected solely from the latent trajectory parameters) influence the rate of acceleration, and therefore the rate of change and actual level, of the outcome variable at time t.

Model fitting

The initial attempt to fit this model to the data resulted in convergence problems. Preliminary analyses had indicated difficulties with estimating the residual variance of the initial growth component in the male group. Constraining this quantity and the associated covariances to zero resulted in a model that fit the data well, χ2(99, N = 356) = 110.46, p > .20. This change has minimal conceptual implications, as it only affects the prediction of Grade 1 behavior problems. The residual variance of the acceleration component was not significantly different from zero in either group, ps >. 15; the variance was retained in the model to allow for effects of divorce–separation in subsequent modeling. The effect of the previous level of externalizing behavior problems on rate of acceleration was significant and negative for girls, b = −0.265, SE = 0.101, t = 2.61, p < .01; none of the other proportional change effects were individually significant. The effects of race on the three trajectory parameters were significant for girls, likelihood ratio (LR) χ2(3, N = 356) = 9.50, p < .03; but not for boys, LR χ2(3, N = 356) = 1.32, ns (none of the tests of race effects on individual growth parameters were significant). All effects were retained for both groups; exploration of these effects will be reserved for a later section.

Effects of Divorce–Separation

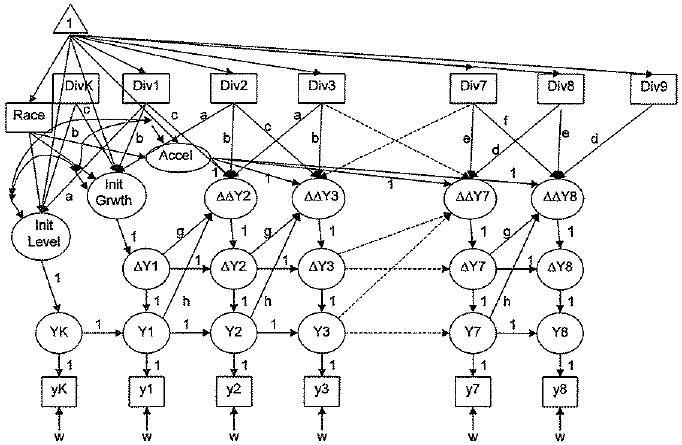

The divorce–separation measures were incorporated as a series of dichotomous indicators. Their relations to the externalizing behavior problem trajectories are represented in Figure 2. Divorce–separation at time t was modeled as affecting behavior at time t − 1, t, and t + 1 to represent the ongoing processes involved in a major life change, including the effects of predivorce stress on the child's behavior. The direct effects of divorce–separation were on the acceleration variables (and, in the early years, directly on the growth parameters), and indirectly on the rate of change and level.

FIGURE 2.

Second-order dual change score model with effects of divorce.

Model building

In the initial modeling, the effects of divorce were constrained to be equal across years—that is, the effect of divorce–separation at time t on behavior problems at t − 1 was constant across t. This model fit the data well, χ2(267, N = 356) = 308.87, p < .07. Inspection of the correlation matrix, however, indicated that the effects of divorce–separation did appear to vary over time. A second model, depicted in Figure 2, allowed the effects of a divorce or separation to vary depending on whether the event occurred during elementary school (through Grade 5) or after (Grades 6–9). This model also fit the data well, χ2(267, N = 356) = 285.99, p > .20; and significantly better than the more constrained model, LR χ2(6, N = 356) = 22.88, p < .001. It accounted for substantial portions of the variance in the observed externalizing behavior problems variables, ranging from .45 to .57 for girls; and .49 to .60 for boys (the residual variances were constrained to be equal across time within gender; the R2 values vary with the observed variances). Further results and conclusions are based on this model. Key parameter estimates are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Parameter Estimates From the Trajectory Model

| Parameter | Estimate | SE | Estimate/SE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | |||

| Interceptsa | |||

| Initial level | 0.821 | 0.065 | 12.61*** |

| Initial growth | −0.003 | 0.015 | 0.22 |

| Acceleration | 0.187 | 0.060 | 3.11** |

| Residual variancesa | |||

| yt | 0.497 | 0.025 | 20.29*** |

| Initial level | 0.465 | 0.080 | 5.84*** |

| Initial growth | 0.010 | 0.008 | 1.22 |

| Acceleration | 0.022 | 0.013 | 1.66† |

| Proportional change | |||

| Yt−1 on ΔΔYt (h) | −0.225 | 0.072 | 3.14** |

| ΔYt−1 on ΔΔYt (g) | 0.364 | 0.234 | 1.56 |

| Effects of race | |||

| African American on initial level | −0.074 | 0.218 | 0.34 |

| African American on initial growth | 0.101 | 0.060 | 1.68† |

| African American on acceleration | 0.015 | 0.051 | 0.29 |

| Effects of early divorce/separation (Div/Sep) | |||

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt−1 (a) | −0.097 | 0.064 | 1.51 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt (b) | 0.176 | 0.099 | 1.78† |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt+1 (c) | −0.090 | 0.055 | 1.64 |

| Effects of late divorce/separation (Div/Sep) | |||

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt−1 (d) | 0.110 | 0.170 | 0.65 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt (e) | −0.441 | 0.420 | 1.05 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt+1 (f) | 0.366 | 0.427 | 0.86 |

| Boys | |||

| Interceptsa | |||

| Initial level | 1.265 | 0.084 | 15.01*** |

| Initial growth | 0.135 | 0.084 | 1.61 |

| Acceleration | −0.291 | 0.138 | 2.11* |

| Residual variancesa | |||

| yt | 0.639 | 0.028 | 22.59*** |

| Initial level | 0.706 | 0.095 | 7.43*** |

| Initial growth | — | — | — |

| Acceleration | 0.058 | 0.034 | 1.70† |

| Proportional change | |||

| Yt−1 on ΔΔYt (h) | 0.217 | 0.097 | 2.23* |

| ΔYt−1 on ΔΔYt (g) | −1.494 | 0.312 | 4.80** |

| Effects of race | |||

| African American on initial level | −0.076 | 0.321 | 0.24 |

| African American on initial growth | 0.309 | 0.318 | 0.97 |

| African American on acceleration | −0.062 | 0.092 | 0.67 |

| Effects of early divorce/separation (Div/Sep) | |||

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt−1 (a) | 0.003 | 0.133 | 0.02 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt (b) | 0.364 | 0.181 | 2.01* |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt+1 (c) | −0.113 | 0.186 | 0.61 |

| Effects of late divorce/separation (Div/Sep) | |||

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt−1 (d) | 0.016 | 0.176 | 0.09 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt (e) | 0.314 | 0.253 | 1.24 |

| Div/Sept on ΔΔYt+1 (f) | −1.070 | 0.247 | 4.33*** |

Note. n (girls) = 168, n (boys) = 188.

Controlling for race.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Gender differences

The next step in the analysis was to test for gender differences in parameter estimates. The estimated parameters were grouped by type of effect (e.g., the 3 parameters for effects of early divorce), and equality constraints were tested by group. Each set of constraints was tested independently against the full model; Table 4 summarizes the results. There were significant gender differences in the effects of early divorce–separation, p < .03; and marginal differences in the effects of late components, p < .07; as well as all of the other model components except race.

TABLE 4.

Tests of Gender Differences in Parameter Estimates

| Parameter | LR χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residual variance of y | 16.41 | 1 | <.001 |

| Intercept of initial level | 16.48 | 1 | <.001 |

| Intercepts of growth components (initial growth and acceleration) | 7.41 | 2 | .03 |

| Proportional change effects (g, h) | 17.88 | 2 | <.001 |

| Effects of race | 0.80 | 3 | ns |

| Effects of early divorce–separation (a, b, c) | 9.24 | 3 | .03 |

| Effects of late divorce–separation (d, e, f) | 7.27 | 3 | .07 |

Note. n (girls) = 168, n (boys) = 188. LR = likelihood ratio.

Tests of model components

Finally, the clusters of effects (except for residual variance and intercepts of the initial level, which have 1 df each and are thus redundant with Table 3) were evaluated for significance. Where there was no evidence of a gender interaction (p > .10), the effects were tested after applying the equality constraints to maximize power. Other effects were tested separately by gender. The results appear in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Tests of Parameter Estimates

| Parameter | LR χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepts of growth components (initial growth and acceleration) | |||

| Girls | 4.02 | 2 | .14 |

| Boys | 3.81 | 2 | .15 |

| Effects of race | |||

| All | 10.27 | 3 | .02 |

| Proportional change effects (g, h) | |||

| Girls | 6.49 | 2 | .04 |

| Boys | 12.97 | 2 | .002 |

| Effects of early divorce–separation (a, b, c) | |||

| Girls | 5.59 | 3 | .14 |

| Boys | 17.21 | 3 | <.001 |

| Effects of late divorce–separation (d, e, f) | |||

| Girls | 3.18 | 3 | .37 |

| Boys | 9.88 | 3 | .02 |

Note. N (total) = 356; n (girls) = 168, n (boys) = 188. LR = likelihood ratio.

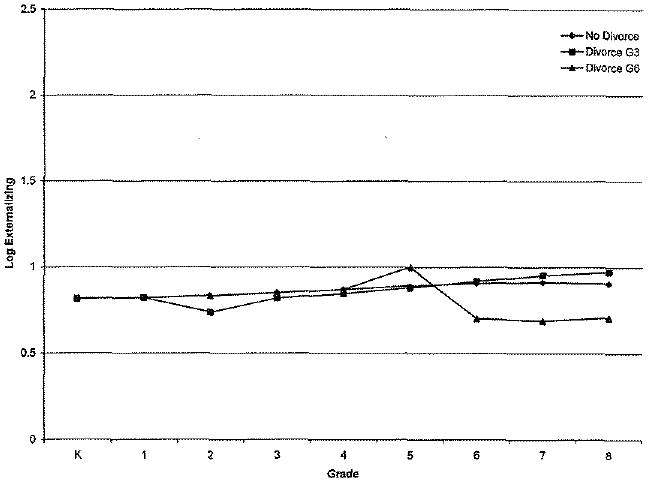

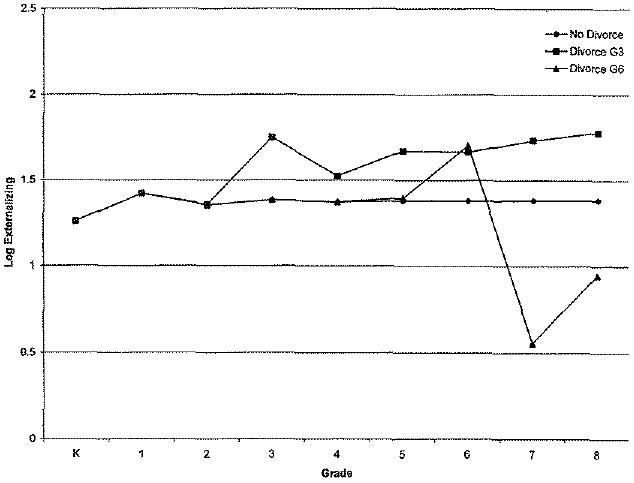

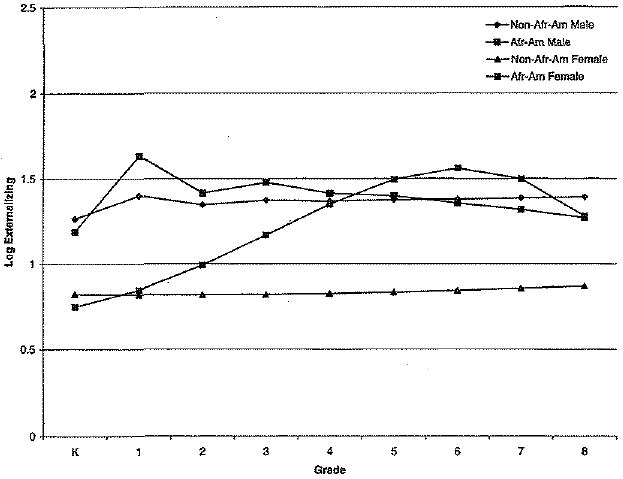

As Table 5 indicates, significant effects of divorce–separation were found for boys for both early and late events. These effects significantly differed from each other based on testing of equality constraints across the two periods, χ2(3, N = 356) = 19.76, p < .001. Divorce–separation showed no significant effects on externalizing behavior problems for girls at either period. Figure 3 depicts model-implied trajectories for girls (3A) and boys (3B), given no divorce–separation and divorce–separation at each of two representative timepoints, Grades 3 and 6.

FIGURE 3.

FIGURE 3a Representative model-implied trajectories of externalizing behavior problems for girls.

FIGURE 3b Representative model-implied trajectories of externalizing behavior problems for boys.

As shown, boys experiencing an early divorce–separation show an elevation in externalizing behavior problems beginning the year of the event and persisting, whereas boys experiencing a later divorce–separation show an elevation in problems at the time of the event, followed by a decline below the baseline level the year after the divorce–separation, persisting into following years. The proportional change aspects of the model result in a sensitivity to initial conditions in that the effect magnitudes as they play out over time will be a function of the individual's predivorce levels and growth patterns of behavior problems. The data for Figure 3 are based on individual growth parameters at the means, and thus the trajectories presented the most typical pattern in terms of indicated effects. For interpretation, note from Tables 1 and 2 that the standard deviations of the externalizing variables approximate 1.0 in most years for girls and are slightly higher for boys.

Race also showed a significant impact on the trajectory parameters when the impact was constrained to be equal across gender. Model-implied trajectories for African American and non-African American boys and girls in the absence of divorce or separation are shown in Figure 4. Note that the trajectories for girls show a substantial apparent difference by race, but this is not true for boys; although the structural coefficients were constrained to be equal. This is a result of the gender difference in the proportional change coefficients. As indicated in Table 3, for girls the estimate is positive for the effect of ΔYt−1 on ΔΔYt, and negative for the effect of Yt−1 on ΔΔYt, whereas the reverse is true for boys (of these, only the effect of ΔYt−1 for boys is individually significantly different from zero). Therefore, the early levels and rates of change play out in substantially different patterns over time.

FIGURE 4.

Model-implied trajectories by race and gender in the absence of divorce.

Discussion

This study suggests that the developmental course of externalizing behavior problems in relation to children's experience of their parents' divorce depends on the child's gender and on the timing of the divorce. Specifically, the trajectory of girls' externalizing behavior problems was not affected by experiencing their parents' divorce, regardless of whether the divorce occurred during elementary or middle school. In contrast, experiencing their parents' divorce did alter the trajectory of boys' externalizing behavior problems, but the direction of the effect depended on the timing of the divorce. Boys who were in elementary school when their parents divorced showed an increase in externalizing behavior problems in the year of the divorce, and this elevated level of behavior problems persisted in the years following the divorce. Boys who were in middle school when their parents divorced, however, showed an increase in externalizing behavior problems in the year of the divorce followed by a decrease in externalizing behavior problems to below their baseline levels in the year after the divorce; this decrease persisted in the following years.

The complexity of these findings demonstrates both the benefit and the challenge of applying sophisticated longitudinal models to the study of developmental processes. First among the benefits, this approach incorporates information about the timing of divorce–separation in a more precise way than is commonly found in research on the topic (e.g., Cherlin et al., 1998; Karney & Bradbury, 1995b). By linking the specific year in which the event occurs to the change in behavior problems in and around that year, the researcher can model the effects as they develop. Modeling the baseline trajectory, meanwhile, allows the researcher to distinguish those effects from the growth processes that occur in the outcome in the absence of the specified events. As in any longitudinal study, the selection of occasions of measurement can help or hinder understanding of the processes involved; given a useful interval, this approach allows full use of the timing information available. A related benefit of modeling divorce as occurring in particular time periods is the natural treatment of multiple divorce events. In this model, divorces occurring in multiple years can be included and have a cumulative effect on the outcome (although they are assumed to have identical effects in this study). This stands in contrast to modeling divorce as a single indicator of any number of events occurring in the specified time periods.

The benefit of the complexity for capturing the process unfolding in time can be seen particularly in Figure 3B. By modeling divorce as affecting behavior problems in the years prior to, coinciding with, and following the event, intricate effects can be traced. In the case of a boy who experiences a divorce in Grade 6, an increase relative to the baseline is predicted beginning in Grade 6, followed by a decrease in Grade 7. Further, the proportional change aspects of the model allow for the impact on the trajectory to continue beyond the years modeled as being directly affected.

In addition to these aspects of the latent difference form of the growth model, certain benefits accrue from moving the problem into an SEM framework. Two such features drawn on for this study were the graceful handling of missing data (maximum likelihood estimation from incomplete data) and the ability to construct multiple group models in a precise fashion. Certain more general benefits—particularly, the explicit modeling of measurement and the ability to extend the structural relations between constructs—were not exploited. The measurement model was ignored for the sake of simplicity: The models are quite complex at the structural level alone, although they are based on relatively few estimated parameters. The lack of additional relevant constructs is a broader issue for the study.

Many scholars have argued that differences in adjustment between children whose parents do and do not divorce are not solely attributable to experiencing divorce (see Hetherington et al., 1998). For example, there are differences between these families not only in terms of the experience of parental divorce but also in terms of family income (McLanahan & Booth, 1989), interparental conflict (Davies & Cummings, 1994), parents' psychological well being (Hetherington, 1989), and the quality of parent–child interactions (Demo & Acock, 1996). Perhaps most important in terms of processes proximal to the child, divorce and its associated parental stress and depression is sometimes accompanied by changes in parental management techniques, including less effective and consistent discipline (Martinez & Forgatch, 2001), less monitoring (Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989), and more parent–child conflict (Demo & Acock, 1996). Statistically controlling for these other factors generally attenuates or even eliminates the effects of divorce on children's adjustment (McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Vandewater & Lansford, 1998).

In this study we did not have consistent measures over time of interparental conflict, income, and other variables that are potentially confounded with the experience of divorce. It is possible that our finding of a decline in externalizing behavior problems for boys who experience their parents' divorce in middle school reflects a positive response to diminished conflict that may be associated with divorce. This explanation would be consistent with findings that for children whose parents engage in high levels of overt conflict, divorce is associated with improved adjustment (Amato et al., 1995). Because boys are more likely to be exposed to their parents' conflict than are girls (Cummings, Davies, & Simpson, 1994; Grych & Fincham, 1990), boys may be more likely than girls to benefit from divorce if the divorce results in less exposure to conflict. This explanation, however, does not account for why boys whose parents divorced in kindergarten through Grade 5 experienced an increase in externalizing behavior problems in the year of the divorce that persisted into later years. This result is consistent with other findings that children whose parents divorce exhibit more adjustment problems than do other children (e.g., Cherlin et al., 1998). We did not find effects of either early or later divorce on externalizing behavior problems of girls. Perhaps this reflects the pattern of larger effects of divorce on boys than girls that has been reported in the literature (Amato, 2001; Amato & Keith, 1991). It is also possible, however, that effects of divorce on girls are manifested in other adjustment outcomes such as internalizing problems or the quality of social relationships (Emery, Hetherington, & DiLalla, 1985; Hetherington, Cox, & Cox, 1982). Future research with measures of family processes such as interparental conflict and attention to other adjustment outcomes will help clarify these findings.

The exploration of race effects highlights further areas to which attention is needed in this approach. Although race was included as a covariate in our models, we did not have a large enough sample of African Americans to fully explore how race might moderate the effects of divorce on children's externalizing behavior problems. African Americans have higher rates of divorce compared to European Americans (Kposowa, 1998; Orbuch, Veroff, Hassan, & Horrocks, 2002). Moreover, it is estimated that 45% of European American youth will spend some amount of time in a single-parent home, compared to 86% of African American youth (Garfinkel & McLanahan, 1986). In this sample, 33% of the African American children had biological parents married to one another at the initial assessment point in kindergarten, compared to 71% of the non-African American children. When the child was born, 38% of the African American children's parents were married to one another, compared to 78% of the non-African American children's parents. Therefore, in this study a smaller percentage of African American children were included in the subsample that could have experienced their parents' divorce.

What is less clear than the differences in divorce rates is whether race moderates the association between parents' divorce and children's adjustment. Some suggest that divorce may have a less negative effect for African American children than for European American children (Jeynes, 2002). Specifically, researchers have suggested that because African American children tend to experience less of a decrease in household income following a divorce and African American single mothers are more likely to stay at home with their children (Laosa, 1988), these factors may mitigate the effects of divorce on African American youth. Studies assessing these effects have produced mixed results. Consequently, more research is needed to determine the influence of divorce on minority youth.

Considering the implications for methodology, there is room for debate on the best way to incorporate moderating effects of race or any other construct in this strategy. In this study, the moderating effects of gender were modeled by a multiple group approach and, in the end, there were few points of contact between the models for each gender. Given a larger sample of African Americans, one possible approach would be a four-group model; another strategy would be to include multiplicative interaction terms between race and divorce. The latter approach would increase the complexity of the model considerably, given the multiple effects of divorce. Even in the former, the application of equality constraints to test race and gender effects and their interactions could have surprising implications. As shown in Figure 4, the effects of race on the trajectories appear to differ by gender. However, the plotted trajectories are based on a model where the effects are constrained to be equal. This is one of the challenges of the elaborate modeling approach: The implications of different features of the model are not necessarily obvious or intuitive.

Substantively, an additional direction for future research is to compare effects of divorce versus effects of marital separation on children's adjustment. Consistent with the approach used in many other studies (e.g., Amato et al., 1995; Cherlin et al., 1991; Zill et al., 1993), data collected in this study reflected whether parents had divorced or separated in a given year. This is justified to a certain degree because most marital separations end in divorce within 3 years (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002), and marital separation may be the key event in relation to children's adjustment regardless of whether it is accomplished through legal divorce (Morgan & Rindfuss, 1985). Nevertheless, empirical examinations of adjustment trajectories in relation to the experience of marital separation compared to the experience of legal divorce would clarify understanding of these potentially disparate effects. In a study with more detailed measurement of these events, the potential differences could be readily explored with the change score models. Divorce and separation could be modeled as two different independent variables at each time, and their effects compared in a series of models.

Conclusion

Amato and Keith (1991) concluded from their meta-analysis that “methodologically unsophisticated studies may overestimate the effects of divorce on children” (p. 36). Using methodologically rigorous approaches is thus crucial to understanding whether and how the experience of their parents' divorce affects children's adjustment. This work addresses this issue. By constructing models that imply statements about the constructs that are consistent with the existing knowledge base, that fit the data well, and that allow for flexible specification of effects, researchers can explore and test detailed hypotheses about the effects of divorce and separation. It is difficult to make strong, general claims about the specific findings on divorce; in the current state of the literature, almost any finding can have some support and some contradiction. Under the constraints of the available data, this study leaves open questions about the effects of constructs related to divorce, about the moderating effects of race, and about differences in the effects of divorce versus separation—all of which are likely to be important to a full understanding of the processes. However, the sophistication of the modeling can only aid in developing further studies of these effects, and as similar models come to be used more widely, their properties will be better understood.

Acknowledgments

The Child Development Project has been funded by Grants MH42498 and MH56961 from the National Institute of Mental Health and HD30572 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and support for this study was provided by a generous anonymous donation to the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University.

We are grateful to the parents, children, and teachers who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Some mothers reported experiencing a divorce or separation in multiple years. The analytic method can handle this elegantly. Conceptually, this could have occurred for several reasons. For example, if a mother reported two divorce–separation events, this could have reflected a separation in 1 year and a divorce in a subsequent year. Indeed, there were 31 mothers who reported two divorce–separation events. There were 17 mothers who reported experiencing more than two divorce–separation events. Of these 17, 9 reported experiencing divorce–separation events in three or more consecutive years. It is difficult to determine with certainty what is happening in the lives of this small subset because some report intervening remarriage and reconciliation events and some have intervening years of missing data. These cases have not been treated differently in the analyses. It seems unlikely that the ambiguity conferred by these few cases would substantially influence the results.

Contributor Information

Patrick S. Malone, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Jennifer E. Lansford, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Domini R. Castellino, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Lisa J. Berlin, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

Kenneth A. Dodge, Center for Child and Family Policy, Duke University

John E. Bates, Department of Psychology, Indiana University

Gregory S. Pettit, Department of Human Development & Family Studies, Auburn University

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for Teacher's Report Form and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Teacher's Report Form and Teacher Version of the Child Behavior Profile. Burlington: University of Vermont; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD, Furstenberg FF. How marital dissolution affects children: Variations by age and sex. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:540–549. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Family process in one-parent, stepparent, and intact families: The child's point of view. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49:327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Children of divorce in the 1990s: An update of the Amato and Keith (1991) meta-analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:355–370. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Keith B. Parental divorce and the well-being of children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:26–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR, Loomis LS, Booth A. Parental divorce, marital conflict, and offspring well-being during early adulthood. Social Forces. 1995;73:895–915. [Google Scholar]

- Block JH, Block J, Gjerde PF. The personality of children prior to divorce: A prospective study. Child Development. 1986;57:827–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Vital Health Statistics. Vol. 23. National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Retrieved April 26, 2004, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_022.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Cherlin AJ, Kiernan KE. The long-term effects of parental divorce on the mental health of young adults: A developmental perspective. Child Development. 1995;66:1614–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Lansdale PL, Hetherington EM. The impact of divorce on life-span development: Short and longterm effects. In: Baltes PB, Featherman DL, Lerner RM, editors. Life-span development and behavior. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1990. pp. 105–150. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ. Going to extremes: Family structure, children's well-being, and social science. Demography. 1999;36:421–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Chase-Lansdale PL, McRae C. Effects of parental divorce on mental health throughout the life course. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Furstenberg FF, Chase-Lansdale PL, Kiernan KE, Robins PK, Morrison DR, et al. Longitudinal studies of effects of divorce on children in Great Britain and the United States. Science. 1991;252:1386–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.2047851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT, Simpson KS. Marital conflict, gender, and children's appraisals and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Cummings EM. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:387–411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, Acock AC. Family structure, family process, and adolescent well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:457–488. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty WJ, Needle RH. Psychological adjustment and substance use among adolescents before and after parental divorce. Child Development. 1991;62:328–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science. 1990;250:1678–1683. doi: 10.1126/science.2270481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Hetherington EM, DiLalla LF. Divorce, children, and social policy. In: Stevenson HW, Sigal AE, editors. Child development research and social policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1985. pp. 189–266. [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Waldron M, Kitzmann KM, Aaron J. Delinquent behavior, future divorce or nonmarital childbearing, and externalizing behavior among offspring: A 14-year prospective study. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:568–579. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel I, McLanahan S. Single mothers and their children. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Grych JH, Fincham FD. Marital conflict and children's adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:267–290. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR. The nurture assumption: Why children turn out the way they do. New York: Free Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM. Coping with family transitions: Winners, losers, and survivors. Child Development. 1989;60:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Bridges M, Insabella GM. What matters? What does not? Five perspectives on the association between marital transitions and children's adjustment. American Psychologist. 1998;53:167–184. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Cox M, Cox R. Effects of divorce on parents and children. In: Lamb M, editor. Nontraditional families: Parenting and child development. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1982. pp. 233–288. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1979. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes W. Divorce, family structure, and the academic success of children. Binghamton, NY: Haworth; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Assessing longitudinal change in marriage: An introduction to the analysis of growth curves. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995a;57:1091–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, method, and research. Psychological Bulletin. 1995b;118:3–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kposowa AJ. The impact of race on divorce in the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29:529–548. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, Fields JM. Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 1996. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Laosa LM. Ethnicity and single parenting in the United States. In: Hetherington EM, Arasteh JD, editors. Impact of divorce, single parenting, and stepparenting on children. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1988. pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, Forgatch MS. Preventing problems with boys' noncompliance: Effects of a parent training intervention for divorcing mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:416–428. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Hamagami F. Latent difference score structural models for linear dynamic analyses with incomplete longitudinal data. In: Collins LM, Sayer AG, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 137–176. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Nesselroade JR. Using multivariate data to structure developmental change. In: Cohen SH, Reese HW, editors. Life-span developmental psychology: Methodological contributions. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1994. pp. 223–267. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS, Booth K. Mother-only families: Problems, prospects, and politics. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:557–580. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan SS, Sandefur G. Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan PS, Rindfuss RR. Marital disruption: Structural and temporal dimensions. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90:1055–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 2.1: Addendum to the Mplus User's Guide. 2002 Retrieved July 10, 2002, from http://www.statmodel.com/version2.html.

- Orbuch TL, Veroff J, Hassan H, Horrocks J. Who will divorce: A 14-year longitudinal study of Black couples and White couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:179–202. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson G, DeBaryshe B, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater EJ, Stewart K, Linn M. The effects of family disruption on adolescent males and females. Adolescence. 1983;18:933–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet JA, Bumpass LL. The National Survey of Families and Households—Waves 1 and 2: Data description and documentation. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin-Madison, Center for Demography and Ecology; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of the Census. Statistical abstract of the United States 1999. 119th. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vandewater EA, Lansford JE. Influences of family structure and parental conflict on children's well-being. Family Relations. 1998;47:323–330. [Google Scholar]

- Videon TM. The effects of parent-adolescent relationships and parental separation on adolescent well-being. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:489–503. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein JS, Blakeslee S. Second chances: Men, women, and children a decade after divorce. New York: Ticknor & Fields; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein JS, Kelly JB. Surviving the breakup: How children and parents cope with divorce. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Zill N, Morrison DR, Coiro MJ. Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent–child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 1993;7:91–103. [Google Scholar]