Abstract

We investigated potential niche separation in two closely related (99.1% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity) syntopic bacterial strains affiliated with the R-BT065 cluster, which represents a subgroup of the genus Limnohabitans. The two strains, designated B4 and D5, were isolated concurrently from a freshwater reservoir. Differences between the strains were examined through monitoring interactions with a bacterial competitor, Flectobacillus sp. (FL), and virus- and predator-induced mortality. Batch-type cocultures, designated B4+FL and D5+FL, were initiated with a similar biomass ratio among the strains. The proportion of each cell type present in the cocultures was monitored based on clear differences in cell sizes. Following exponential growth for 28 h, the cocultures were amended by the addition of two different concentrations of live or heat-inactivated viruses concentrated from the reservoir. Half of virus-amended treatments were inoculated immediately with an axenic flagellate predator, Poterioochromonas sp. The presence of the predator, of live viruses, and of competition between the strains significantly affected their population dynamics in the experimentally manipulated treatments. While strains B4 and FL appeared vulnerable to environmental viruses, strain D5 did not. Predator-induced mortality had the greatest impact on FL, followed by that on D5 and then B4. The virus-vulnerable B4 strain had smaller cells and lower biomass yield, but it was less subject to grazing. In contrast, the seemingly virus-resistant D5, with slightly larger grazing-vulnerable cells, was competitive with FL. Overall, our data suggest contrasting ecophysiological capabilities and partial niche separation in two coexisting Limnohabitans strains.

Bacterioplankton communities in freshwater systems frequently are characterized by the dominance of a relatively small number of clades as defined by 16S rRNA gene phylogenies (4, 50). These genus-like phylogenetic groups usually contribute large fractions to total prokaryotic numbers in typical stagnant freshwater systems (1, 34, 37, 39). While determining ecological differences between the organisms of these rather distantly related 16S rRNA clades is of enormous importance for understanding the mechanisms and factors shaping the diversity and composition of freshwater bacterioplankton (21), it is important to know if such clades actually represent ecologically coherent taxa, or if there is significant ecological variation within a single clade. Recent studies have uncovered ecological differences between closely related organisms within the same 16S rRNA clade (7, 13, 16, 18, 20, 26, 35). Several of these studies compared organisms affiliated with the same clade but originating from ecologically different habitats. To date only a few investigations have examined ecological differences between closely related and coexisting (syntopic) freshwater bacteria (7, 18, 35). For example, niche separation among Vibrionaceae strains coexisting in coastal bacterioplankton was demonstrated (16). Among a broad diversity of sympatric strains, Hunt and coworkers (16) identified phylogenetic subgroups differing in lifestyle (free living or association with different particle size classes) and seasonal preferences.

Here, we investigate if two closely related strains coexisting in the same freshwater habitat differ significantly in their interactions with biological factors. We examined vulnerability to predation by a bacterivorous flagellate, sensitivity to virus assemblages recovered from their native habitat, and the interaction with a competitor of high growth potential. The two strains both were isolated from the same water sample taken from the meso-eutrophic Římov reservoir and belong to the recently proposed betaproteobacterial genus Limnohabitans (11). Within Limnohabitans, these two strains belong to a monophyletic group known as the R-BT065 cluster targeted by a homonymous fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) probe (41), which enabled intensive investigations of the ecology of this abundant bacterioplankton group in several different habitats (1, 15, 28, 29, 34, 37, 38). A recent survey on the distribution of this taxon revealed that it is a ubiquitous member of bacterioplankton communities in a broad variety of pH-neutral freshwater systems (102 systems inspected; see reference 39) that typically comprises ∼5 to 30% of total bacterial cell numbers. Previous investigations indicated a rather homogenous ecology of the R-BT065 group, characterized by the potential for a rapid response to changes of environmental conditions (34, 37, 38, 41) and a high sensitivity to flagellate predation (19, 42).

We hypothesized that the two sympatric strains affiliated with the R-BT065 group would show ecological differences. These strains, designated B4 and D5, represent the most distantly (99.1% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity) related pairing among the R-BT065 strains isolated so far (V. Kasalický, K. Šimek, J. Jezbera, and M. W. Hahn, unpublished data). To reveal ecological differences, the two strains were exposed to different manipulations in a laboratory experiment: (i) each of the R-BT065 strains were always separately cocultured with a fast-growing competitor of the genus Flectobacillus (strain MWH38; see reference 12), (ii) the cocultures were amended by additions of different amounts of a live or heat-killed virus concentrate collected from their home environment, and (iii) in parallel, these cocultures received an axenic bacterivore, Poterioochromonas sp., that was able to feed on all three bacterial strains involved in the study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental organisms.

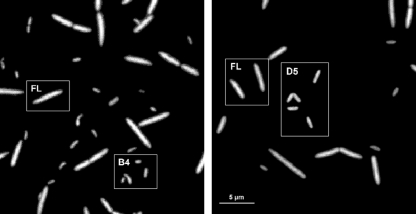

Two bacterial strains, designated B4 and D5 (accession numbers FM165536 and FM165535, respectively), that are being described currently (V. Kasalický et al., unpublished) as novel members of the genus Limnohabitans (11), were isolated from a single water sample from the surface layer of the freshwater meso-eutrophic Římov reservoir in South Bohemia (48°50′56”N, 14°29′26”E). They belong to the R-BT065 subcluster of Betaproteobacteria targeted by the probe R-BT065 (for the probe targets, see reference 41). Of several strains isolated from the R-BT065 cluster, the isolates B4 (small rods) and D5 (larger rods) (Fig. 1) are phylogenetically distinct within the cluster (V. Kasalický, unpublished data).

FIG. 1.

Microphotographs of the B4 and D5 strains (from the R-BT065 cluster of Betaproteobacteria) cocultured with FL (Flectobacillus sp. strain MWH38) documenting that the cells of the respective strains were clearly visually distinguishable in the cocultures. Typical representative morphotypes are highlighted in white frames. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Flectobacillus sp. strain MWH38 (designated FL here) is a fast-growing, filament-forming bacterium affiliated with the phylum Bacteroidetes that was isolated from Lake Heidbergsee, Germany (12) and classified based on 16S rRNA phylogeny (accession number AJ011917).

The mixotrophic flagellate predator Poterioochromonas sp. DS (formerly designated Ochromonas sp. DS but closely related to Poterioochromonas malhanensis), was isolated by Doris Springmann from Lake Constance (accession number AM981258) (9). The axenic flagellate culture used in the experiment was maintained in dim light and fed twice a month with heat-killed bacteria as described previously (12).

Experimental design and sampling.

Prior to the experiment, the three strains B4, D5, and FL were subcultured separately in 40 mg liter−1 of NSY medium (14) and in exponential phase (second day) were reinoculated three times into a fresh medium of the same concentration to maintain the cultures in exponential growth. The second day after the last reinoculation, the bacteria were counted and then mixed to adjust an initial numerical ratio of ∼3:1 to 4:1 of one of the representatives of the R-BT065 cluster (either D5 or B4, with the starting concentration of ∼3 × 105 and 4 × 105 cells ml−1, respectively) cocultured with FL (∼1 × 105 cells ml−1). This ratio was applied to compensate for much smaller cell volumes of the strains B4 and D5 compared to that of FL (Fig. 1) and thus adjust the biomass ratio between the two cocultured strains approximately to 1:1 at the beginning of the experiment. Experimental treatments, run in 300-ml Erlenmeyer flasks filled with 150 ml of the sterile NSY medium (40 mg liter−1), were incubated in the dark at 18°C.

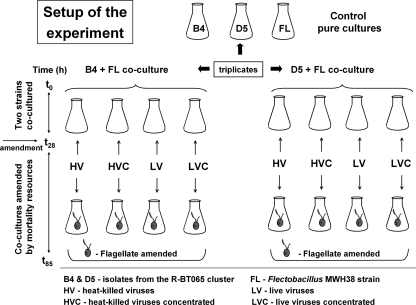

The triplicate experimental setup is illustrated in Fig. 2. At time point 0 h (t0), (i) triplicate flasks were inoculated with a pure culture of the B4, D5, and FL strains (the control monocultures), and (ii) a total of 24 flasks were inoculated with either a mixture of the B4+FL or a mixture of the D5+FL strains. These cocultures (a sum of 48 flasks) were grown for 28 h, reaching total bacterial concentrations of 1.5 × 107 to 2.5 × 107 ml−1. Since no phage isolates for the bacterial strains are in culture, a natural virus assemblage (viral concentrate) from the reservoir where the strains were isolated was used in the experiments (see below). At t28, six replicates of both B4+FL and D5+FL cocultures were amended with (i) heat-killed viruses at the in situ virus/bacteria ratio (VBR) of approximately 9 (designated HV), (ii) with ∼3.5-times-more-concentrated heat-killed viruses (HVC), (iii) with live viruses in at an approximate VBR of 9 (LV), and (iv) with ∼3.5-times-more-concentrated live viruses (LVC). The heat-inactivated viruses were added to compensate for the organic material added along with live viruses. Bacterial carbon (C) content estimated through the cell sizing (see reference 32 for details) of the bacterial strains and literature data on C content in viral particles (45) allowed us to tentatively estimate an enrichment factor, i.e., the amount of C introduced with the virus manipulation as related to the total biomass of the cocultured bacterial strains at t28. This virus-bound C enrichment represented ∼2 and ∼7% of bacterial C present in basal virus and concentrated virus treatments, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Experimental design and major steps of manipulating the growth of studied bacterial strains by sources of bacterial mortality. At t28, the treatments with B4+FL or D5+FL exponentially growing coculture were amended with heat-killed viruses (designated HV), with ∼3.5-times-more-concentrated heat-killed viruses (HVC), with live viruses (LV), and with ∼3.5-times-more-concentrated live viruses (LVC). In parallel, triplicates of all virus-amended treatments received a bacterivore (an axenic culture of Poterioochromonas sp.) capable of grazing on all cocultured bacterial strains (for details of cell size and morphology, see the legend to Fig. 1).

Immediately after virus amendments, half of all of the cocultured treatments (i.e., triplicates of HV, HVC, LV, and LVC of both B4+FL and D5+FL cocultures) (Fig. 2) received ∼1,900 cells ml−1 of an axenic culture of a bacterivore, Poterioochromonas sp., starved for the last 7 days prior to the inoculation. The absence of heat-killed bacteria in the Poterioochromonas culture was checked microscopically.

Thus, between t28 and t85, the amended cocultures were exposed to treatments of either a single mortality source factor (viruses or a bacterivorous flagellate) or both mortality factors together (Fig. 2). Triplicate subsamples (10 to 15 ml) were taken at 0, 18, 28, 43, 67, and 85 h and used for the quantification of microbes (see below). Toward the end of the experiment (t85) a minor proportion of contaminating cells overlapping in size range with B4 or D5 first appeared in live virus-amended cocultures (always <5% of the total of either the B4 or D5 strain). Thus, after employing FISH (with the R-BT065 probe), the total numbers of B4 and D5 strains at t85 were corrected for the number of the R-BT065-positive cells. In contrast, the cells of the FL strain were clearly distinguishable (by their typical long-rod shape morphology and size) from other morphotypes throughout the whole experiment (Fig. 1).

Flow-cytometric enumeration of viruses and bacteria.

Triplicate samples for viral and bacterial cell counting (1 ml each) were fixed in glutaraldehyde (0.5% final concentration) and in a fresh mixture of 1% paraformaldehyde plus 0.05% glutaraldehyde (final concentration), respectively, for 30 min at 4°C in the dark, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further analysis. For viral counts, samples were prepared as previously described (3). Samples were stained with diluted SYBR green I solution (2.5 mM final concentration; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in a 80°C water bath for 10 min before being run in a flow cytometer. Samples for bacterial counts were stained for 10 min at room temperature in the dark with Syto13 (2.5 mM final concentration; Molecular Probes). All samples were run later in a desktop FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) equipped with a laser emitting at 488 nm, and MilliQ water was used as the sheath fluid. To keep a suitable rate of particle passage per second (6), samples for viral counts were 50- to 1,000-fold diluted in autoclaved and 0.2-μm-prefiltered TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0). The viral concentration was determined from the flow rate, which was calculated by weighing a sample before and after 5-min runs of the cytometer. Samples for bacterial counts were diluted two to four times with MilliQ water to keep the rate of particle passage below 800 particles per second, and yellow-green 0.92-μm latex beads (Polyscience Europe, Eppelheim, Germany) were used as internal standards.

Bacterial and flagellate abundance and bacterial sizing.

Samples were fixed with formaldehyde (2% final concentration, vol/vol), stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; final concentration, 0.1 μg ml−1, wt/vol), and enumerated by epifluorescence microscopy (Olympus AX 70). In each case, two replicates from each treatment first were counted microscopically for the cocultured B4 or D5 strain with FL at 0, 18, 28, and 43 h. The same samples also were counted by flow cytometry (FCM), which easily discriminated, based on side scatter, between large cells of FL and the much smaller cells of either B4 or D5 cocultured with FL (Fig. 1). The counts determined by both approaches yielded a tight linear correlation for the pooled data for the B4 and D5 strains (r2 = 0.922, n = 128, P < 0.0001). Thus, the abundance data presented for strains B4 and D5 throughout the whole experiment are based on FCM counts of the triplicate treatments (Fig. 3), except for the t85 data, where the FCM counts of the B4 and D5 strains were corrected for a very minor proportion of small cells that did not hybridize with the R-BT065 probe (see details described above). However, FL cells always were quantified by epifluorescence microscopy, since the presence of short filaments in samples in some cases resulted in the significant underestimation of total FL counts via FCM, while the single cells in filaments visually were easily distinguishable. Cell sizing, based on measuring cell width and length parameters in DAPI-stained preparations, was conducted by using the semiautomatic image analysis system LUCIA D (Lucia 3.52; Laboratory Imaging, Prague, Czech Republic) as described by Posch et al. (32).

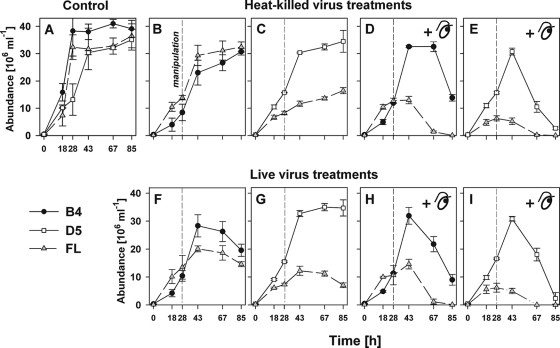

FIG. 3.

Time-course changes in bacterial abundance of the strains B4, D5, and FL in pure cultures (A) and in the cocultures B4+FL (B, D, F, and H) and D5+FL (C, E, G, and I) amended with heat-killed (B to E) or live viruses F to I) and a flagellate predator, Poterioochromonas sp. (D, E, H, and I). The vertical dashed line indicates experimental amendments at t28. For a further explanation of the experimental design, see Fig. 2. Values are means from triplicate treatments, and vertical bars show ± 1 SD.

For flagellate Poterioochromas sp. enumeration, samples were processed as described in Šimek et al. (41). The number of flagellates (>400 cells per sample) was counted at 28 (just after their inoculation), 67, and 85 h.

Virus concentrate.

The water sample for concentrating viruses was collected on 3 June 2008 about 250 m off the dam of the meso-eutrophic Římov reservoir, a canyon-shaped reservoir in South Bohemia, Czech Republic (see reference 40 for details). Bacteria from a 100-liter water sample were removed by using a 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate cartridge (Durapore; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Viruses (∼1.7 × 107 ml−1 in the original sample) in the filtrate from the <0.2 μm-pore-size cartridge were concentrated using a 100-kDa polysulfone cartridge (Prep-Scale, Millipore). Half of the virus concentrate (∼60 ml) was exposed to 80°C for 30 min to inactivate viruses (49). The viral concentrate, which was used to amend the treatments (both heat-killed and live; see the design in Fig. 2) contained approximately 8 × 1010 virus particles ml−1.

Presence of lytic viruses: plaque technique.

The strains B4, D5, and FL were grown in 1 g liter−1 NSY medium (14) for 1 day, achieving exponential growth phase with ∼108 cells ml−1. From the treatments with live viruses, concentrated (LVC) (see the experimental design in Fig. 2) duplicate (designated A and B) 1-ml subsamples were centrifuged at 21,381 × g for 5 min to spin down. The supernatant with the virus-sized particles was taken and split into two 500-μl subsamples. Fifty-μl aliquots of the strains B4, D5, and FL were added to the subsamples in a sterile Eppenderf tube and vortexed; the mixture was left for 45 min to allow the viral particles to contact the potential host cells (44). Lawns were made by mix the host cells with viral concentrate in molten soft agar (0.75% at about 40°C) and quickly pouring this mixture over a bottom layer with hard agar (1.5% with NSY medium, 3 g liter−1). After 24 h, colony forming and plaques on the plates were inspected. In addition, using a microbiological loop we took subsamples (in triplicates) by streaking an approximately 5-mm long-line on the surface of the agar in the spaces between well-distinguishable single growing colonies of B4, D5, and FL strains grown for 24 h. The loop with the streaked material was washed in 1 ml of MilliQ particle-free water in a sterile cryovial and preserved for viral counting as described above.

CARD-FISH.

Cells of strain FL were easily distinguishable from the cocultured B4 or D5 strain based on their typical size and cell morphology (Fig. 1). Since live virus amendments (a concentrate of <0.2 μm live particles) could, however, bring some contamination by smaller cells of similar morphology, such as the typical rod-shaped B4 and D5 strains (Fig. 1), the purity of the R-BT065 isolates in the cocultures was checked in all treatments at the end of the study (t85). We applied the catalyzed reporter deposition fluorescence in situ hybridization (CARD-FISH) (30, 36) protocol employing the R-BT065 probe (ThermoHybaid; Interactiva Division, Ulm, Germany), which targets a subcluster of the Rhodoferax sp. BAL47 cluster (50) of Betaproteobacteria.

Statistical analyses.

Prior to statistical testing, bacterial abundance data were normalized by ln transformation. Repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) multiple-comparison posttest (Statistica 7.1.; StatSoft, Inc.) were applied to test for differences in treatment effects.

RESULTS

Bacterial, viral, and flagellate dynamics in batch cultures.

Visually, the three strains were easily distinguishable in all types of cocultures (see the experimental design in Fig. 2 for details), including FL cells, which sometimes were present randomly in short multiple-celled chains (Fig. 1). These observations were confirmed for several time points by using CARD-FISH. Across all treatments, >60% of FL cells were observed as single cells (data not shown).

In controls, the pure strains grew exponentially for the first 28 (B4 and FL) or 43 h (D5) before switching into stationary phase, reaching a maximum cell abundance of ∼35 × 106 ml−1 for D5 and FL strains and ∼40 × 106 ml−1 for the B4 strain (Fig. 3). Note that there was a pronounced difference between cell numbers and biomass yield reached in the stationary phase by the different strains (Fig. 3 and 4), which reflects the larger mean cell volume (MCV) of FL (Fig. 1). Prior to the experimental manipulations (t18), the MCVs of B4, D5, and FL cells were the following (means ± standard deviations [SD]): 0.079 ± 0.014, 0.113 ± 0.002, and 0.867 ± 0.052 μm3, respectively. Notably, we did not find any significant difference in the MCV of the strains between live and heat-killed amended treatments at t67 (P > 0.05, ANOVA), i.e., 39 h after the experimental manipulation.

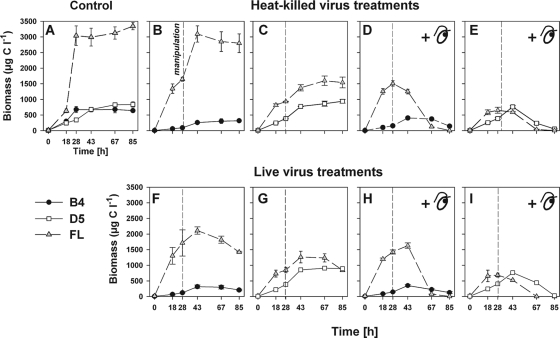

FIG. 4.

Time-course changes in bacterial biomass of the strains B4, D5, and FL in pure culture (A) and in the cocultures B4+FL (B, D, F, and H) and D5+FL (C, E, G, and I) amended with heat-killed (B to E) or live viruses (F to I) and a flagellate predator, Poterioochromonas sp. (D, E, H, and I). The vertical dashed line indicates experimental amendments at t28. For a further explanation of the experimental design, see the legend to Fig. 1. Values are means from triplicate treatments, and vertical bars show ± 1 SD.

Viral particles were added to the cocultures in two different concentrations that showed very similar trends in the corresponding nonconcentrated treatments and in the approximately 3.5-times-more-concentrated treatments (data not shown). On average, these additions yielded a virus-to-total bacteria ratio of 9 in the heat-killed virus (HV) and live virus (LV) treatments, compared to ∼35 in the concentrated heat-killed virus (HVC) and concentrated live virus (LVC) treatments. Generally, viral abundance was stable during the study period in live virus treatments (2 × 108 and ∼7 × 108 viral particles ml−1 in basal and concentrated treatments, respectively), while a trend of decreasing viral numbers was evident in heat-killed virus treatments (likely due to virus decay), with the most marked drop observed in the presence of the flagellate (>0.7 × 108 viral particles ml−1; data not shown).

The bacterivore Poterioochromonas sp. showed very fast growth (doubling time of 11 h), with no significant differences across all predator-amended treatments (P > 0.05, ANOVA), starting from 1.9 × 103 at t28 and ending with ∼6.5 × 104 to 7 × 104 flagellates ml−1 at t85 (data not shown). Thus, both prey mixtures represented a high-quality food source for the flagellate.

Overall effects of experimental manipulations.

At the time of the experimental manipulations when the different mortality factors were introduced (t28), there were no significant differences in the abundance of the respective bacterial strains among different treatments (P > 0.05, Tukey's HSD test). At the end of the incubations the following treatment effects were found, in order of their decreasing significance (Table 1): (i) influence of the flagellate predator (presence versus absence), (ii) species-specific effect of the FL competitor on the growth of B4 and D5 strains and vice versa, and (iii) impacts of both concentrations of live viruses. While the basal virus concentrate affected the population dynamics of each strain, there was no significant difference between basal virus concentration and high virus concentration (Table 1). Thus, in Fig. 3 and 4 we show only bacterial abundance and biomass data for the treatments with the basal-level virus abundance. Nevertheless, we found a significant interaction of the predator with the abundance of viruses (Table 1), and moreover, the interaction of a bacterial strain with a predator differed with the concentration of the live viruses. Thus, in selected cases we also show the data from the virus concentrated treatments (Fig. 5A and B) that differed from the general trends depicted for the treatments amended with the basal virus concentration (Fig. 3), or if we found an evidence of the synergistic effect of two mortality factors in both virus concentrations (Fig. 5C and D).

TABLE 1.

Results of multivariate tests of significance on interactions of strains, viruses, and predator on abundance of bacterial strainsa

| Variable(s) | F | Significance (P) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strain | 95.178 | <0.00001 |

| Virus | 2.885 | 0.02965 |

| Concentrated virus | 10.827 | <0.00001 |

| Predator | 991.404 | <0.00001 |

| Strain + virus | 4.156 | <0.00001 |

| Strain + concentrated virus | 3.804 | 0.00004 |

| Virus + concentrated virus | 0.893 | 0.47365 |

| Strain + predator | 42.634 | <0.00001 |

| Virus + predator | 4.317 | 0.00386 |

| Concentrated virus + predator | 11.029 | <0.00001 |

| Strain + virus + concentrated virus | 1.002 | 0.44954 |

| Strain + virus + predator | 3.480 | 0.00014 |

| Strain + concentrated virus + predator | 4.671 | <0.00001 |

| Virus + concentrated virus + predator | 1.656 | 0.17183 |

| Strain + virus + concentrated virus + predator | 1.186 | 0.29746 |

Shown are the results of multivariate tests of significance (repeated-measures ANOVA) on interactions of strains, the presence of live viruses or live concentrated viruses, and the presence of the predator on the abundance of the bacterial strains (B4, D5, and FL) in the treatments tested between t28 (the experimental manipulation) and t85. See the experimental design in Fig. 2 for details. The bacterial strains (B4, D5, and FL), the presence of live viruses in two concentrations, and the presence of the flagellate predator (Poterioochromonas sp.) were independent variables in the statistical analysis. Significant relationships (P < 0.05) are in boldface.

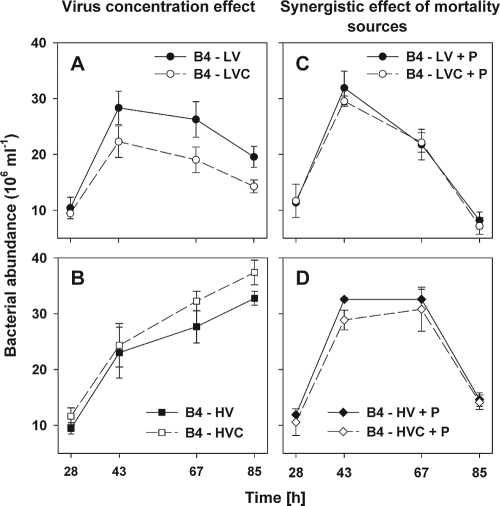

FIG. 5.

Time-course changes in abundance of B4 strains during the period after the sample manipulation (t28 to t85). (A) Example of the virus concentration effect, when the abundance of strain B4 was significantly lower at t67 and t85 (P < 0.01, Tukey's HSD test) in the LVC than in the basal live virus treatment (LV). (B) Trends in B4 abundance in HV and HVC treatments. (C) Example of the synergistic effect of both mortality sources (live viruses and a bacterivore) significantly accelerating mortality of B4 strains at t67 and t85 compared to the treatments amended by heat-killed viruses and a bacterivores (D). Treatments labeled + P, e.g., B4 − HV + P, received a bacterivore, Poterioochromonas sp. Values are means from triplicate treatments, and vertical bars show ± 1 SD.

Virus effects on bacterial population dynamics.

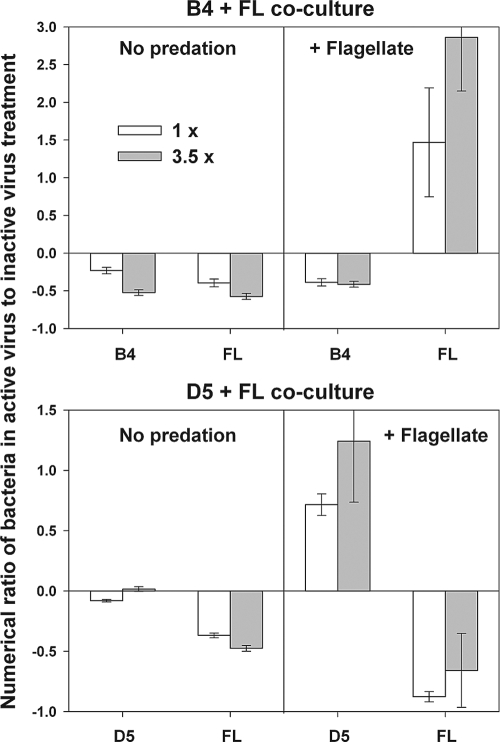

The responses to live virus amendments were different between the strains. In the treatments with live viruses, the abundance of FL and B4 cells decreased at the end of the experiments, whereas D5 remained in the stationary growth phase (Fig. 3). Thus, the data consistently indicated that the strains B4 and FL were vulnerable to live environmental viruses, since the abundance and biomass of the strains significantly decreased at the end of the experiment (P < 0.01, Tukey's HSD test) compared to those of the corresponding heat-killed treatments (Fig. 3 and 4). In contrast, no significant effect (P > 0.05) of live viruses on the dynamics of the D5 strain was detected. We further verified these results by growing each of the three isolates separately in exponential phase, then amending each of the three cultures with live viruses taken from the last time points of the coculture experiments specific to each organism. This mixture was used subsequently to inoculate agar plates that were grown overnight. Agar plates containing either strain B4 or FL exhibited only very scarce colony growth, indicating that these strains were almost completely lysed overnight, whereas no plaques could be found on the D5 lawns. Flow-cytometric counts of virus-type particles taken from these agar plates also were more than one order of magnitude higher for FL and B4 than for D5. Statistical analysis (Table 1) indicated that there were only minor differences detected between the effects of the basal versus 3.5-times-more-concentrated viruses. Nevertheless, we found for the dynamics of B4 at t67 and t85 (Fig. 5A) a more significant negative effect (P < 0.05, Tukey's HSD test) of concentrated live viruses versus less-concentrated live virus treatments.

Positive and negative effects of virus amendments.

To further assess the effects of viral manipulations on the net population growth of bacteria, the abundance of the strains in treatments with active viruses was compared to those of inactivated viruses. To determine this ratio (Fig. 6), we used the last time point in all treatments without the flagellate, or the second-to-last time point, when flagellate grazing had reduced the abundance of FL cells to fairly low levels (<1% of its maximum) (Fig. 3) and accurate counting at the final time point was not possible. In B4+FL treatments, the addition of live viruses had a consistent negative effect on the population growth of both FL and B4. In the presence of the flagellates, the addition of live viruses had a similar negative effect on B4 but strongly stimulated the growth of FL (ca. 2-fold).

FIG. 6.

Numerical ratio of the strains B4, D5, and FL at the end of the experiment (t85) in the treatments with active viruses as related to their abundance in the treatments amended with heat-killed viruses in the absence (labeled no predation) or presence of a flagellate Poterioochromonas sp. (labeled + flagellate). However, in case of the FL strain grown in the presence of the flagellate, this ratio was calculated for the time point t67, since the flagellate drastically decreased FL abundance (2 × 104 to 6 × 104 cells ml−1) by the end of the experiment. The terms 1× and 3.5× refer to basal and concentrated virus additions, respectively. Values are means from triplicate treatments, and vertical bars show ± 1 SD.

A different pattern was observed for D5+FL treatments. The addition of live viruses did not affect the dynamics of D5 in these treatments, but it corresponded with a decrease in FL abundance and biomass (Fig. 3, 4, and 6). When the flagellate was present, the addition of viruses was associated with a marked increase of D5, whereas an apparent negative effect of viruses on FL was strongly enhanced (Fig. 6). In all treatments where significant effects were observed when adding active viruses (as noted above), the 3.5-times-more-concentrated virus treatments showed a similar pattern, but usually they had increased effects compared to those of the less-concentrated virus. Correspondingly, the results of the statistical analysis indicated significant differences in the interaction of mortality sources and of a bacterial strain, with the predator depending on the live virus concentration (P < 0.004, ANOVA) (Table 1).

Combined effects of competition, grazing, and viruses on bacterial biomass yield.

FL clearly was the most productive strain in terms of biomass growth among the coculture treatments. Its biomass yield was ∼5- and 4-fold larger than that of B4 and D5 strains, respectively (Fig. 3 and 4). FL biomass dominated all predator-free cocultures, but this organism was rapidly decimated in the presence of the flagellate (Fig. 3 and 4, t67-85), where the most grazing-resistant strain, B4, became dominant. Notably, strains B4 and FL suffered significant growth deceleration in all amended cocultures compared to the growth of their pure-culture controls (Fig. 3 and 4). In addition, their MCV decreased significantly in all B4+FL cocultures after experimental manipulation (t67) (P < 0.05, t test), whereas no such phenomenon was observed for D5 cocultures (data not shown).

No effect of the FL competitor on the growth of the D5 strain was detected in any virus-amended treatments (Fig. 3), which clearly is in contrast to our observations of strain B4. However, in the absence of viruses, D5 showed enhanced vulnerability to the bacterivore compared to that of B4, but FL was clearly the most heavily grazed strain. Overall, flagellate grazing had the most significant negative effect on the abundance of the strains, but it also generated strain-specific effects on the population dynamics of the cocultured strains (Table 1, Fig. 3). Moreover, we noted a significantly faster decrease of B4 abundance at t67 and t85 (P < 0.05, Tukey's HSD test) in the presence of both mortality factors compared to those of the treatments with the flagellate and heat-inactivated viruses, suggesting a synergistic effect of grazing and live viruses in both concentrations (Fig. 5C and D).

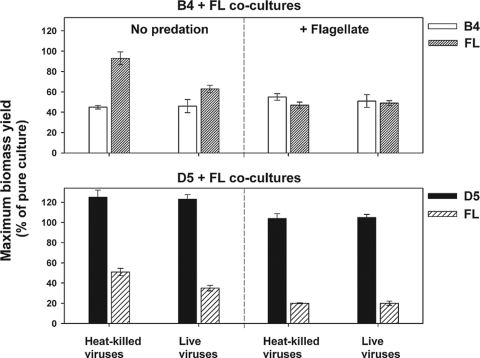

To tentatively assess the complex effect of competition, grazing, and lysis (see the statistical relationships in Table 1) on net growth in quantitative terms, we compared the maximum biomass in pure cultures of the strains to the maximum biomass achieved in the various treatments as a percentage of yield compared to that of the pure cultures (Fig. 7). In the B4+FL treatments, the yield of B4 did not vary much between the presence and absence of flagellates or a combination of both mortality factors. However, its yield in the presence of FL was reduced to roughly 50% compared to that of the pure culture of B4. In contrast, in the absence of flagellates the growth yield of FL was only slightly (3 to 7%) reduced, indicating that the presence of B4 had either no or only a slight effect on the FL biomass yield. However, the live virus treatments decreased FL biomass yield significantly (P < 0.05, t test), from ∼90 to ∼60% compared to that of the heat-killed treatments. The presence of flagellates reduced the yield of FL by 40 to 50% with no distinct effect of the combination of both mortality sources. Growth yields for B4 and FL were roughly similar in the flagellate-amended treatments.

FIG. 7.

Biomass yield of the strains B4, D5, and FL in cocultures amended with bacterial mortality factors expressed as a percentage of the maximum biomass yield achieved in a monoculture (see the control in Fig. 4A) of the respective strain grown in the same medium (40 mg of NSY medium liter−1). The absence (labeled no predation) or presence of a flagellate Poterioochromonas sp. (labeled + flagellate) is indicated. Since no significant effect of two different virus concentrations on maximum biomass yield was detected (P > 0.05, t test), only data for the basal virus concentration are shown. Values are means from triplicate treatments, and vertical bars show ± 1 SD.

In the D5+FL experiments, the biomass yield of D5 was around 100%, with a slight reduction in the presence of the bacterivore and a slight stimulation in its absence (Fig. 7). In bacterivore-free treatments, the growth yield for FL was reduced 40 to 50%, indicating that D5 was a very strong competitor. The presence of the bacterivore largely overrode the effect of live viruses (as seen for FL in B4+FL treatments in Fig. 7), and grazing reduced the FL biomass yield further to only 20 to 28%.

Table 2 summarizes the observed trends in the major ecophysiological features suggesting niche separation for the studied strains based on significant differences in their growth competitiveness and vulnerability to mortality sources (for details, see the text above).

TABLE 2.

Major characteristics suggesting niche separation of strains B4 and D5a

| Ecological aspect | Growth potential and resistance to mortality sources |

|---|---|

| Growth rate in a pure culture | |

| Abundance | B4 > FL > D5 |

| Biomass | FL ≫ D5 > B4 |

| Maximum biomass yield in coculture compared to that of pure culture | |

| D5+FL coculture | D5 > FL |

| B4+FL coculture | FL > B4 |

| Resistance to grazing by Poterioochromonas | B4 > D5 > FL |

| Resistance to virus concentrate from the home | |

| environmentb | D5 ≫ B4 > FL |

Shown is a summary of major characteristics suggesting the niche separation of strains B4 and D5 based on their growth capabilities under different conditions, i.e., in pure cultures, compared to their ecophysiological capabilities and virus and grazing resistance observed in differently amended cocultures (Fig. 3 to 7) and the significance of their effects (Table 1). The order of the descending growth potential or resistance of the respective strain related to the studied parameter is expressed by simple symbols: > and ≫ indicate a modest and dramatic decrease in competitiveness for a studied ecological aspect, respectively. For an explanation of abbreviations used, see the legend to Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Note that the virus assemblage and strain FL originate from geographically distantly located habitats.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation aimed at revealing if two closely related syntopic strains from an environmentally important group of freshwater bacterioplankton differ in ecological adaptation. For the first time, the ecophysiological traits of cultured representatives of the R-BT065 cluster were investigated.

Methodological aspects.

Our results contribute to the scarce knowledge of how bacterial mortality and resource competition may result in niche separation between closely related species (13, 16, 20), exploiting an experimental design that has novel aspects compared to procedures of previous studies dealing with this topic (33, 42, 43, 49). However, competition between the two R-BT065 isolates and their responses to mortality factors could not be studied directly in a coculture, since we lack a strain-specific FISH probe allowing the unambiguous differentiation of the cells that are of similar shapes and sizes (Fig. 1). Thus, we examined the growth responses and resistance of each of the R-BT065 isolates to major mortality sources during competition experiments with FL. Members of the genus Flectobacillus are highly competitive and often form filaments (12) that occasionally can predominate in bacterial biomass in the Římov reservoir plankton during periods of heavy flagellate bacterivory (41, 42) and therefore may represent a direct competitor in situ.

While the abundance of the grazer was controlled in the experiment, the abundance of specific viruses was unknown. No phages have been isolated for the bacterial strains we employed, which have been cultured only recently. This is why we have used an environmental viral community. Also, a PFU approach for quantifying viruses has not been established for the strains. Thus, we did not know the abundances of specific phage in situ. This is why we inoculated two concentrations of this community, one corresponding to approximately in situ values of the VBR and one 3.5-fold elevated in concentration. This mixed approach with isolates and communities is intermediate between using only communities (33, 49) or only isolates (22). Statistically significant effects of viruses detected in our study (Table 1, Fig. 3 and 5) suggest that this mixed approach was successful.

Effects of viruses and a bacterivore on population dynamics of the studied strains.

There is a considerable debate with regard to the major sources of bacterial mortality and their possible interactions as prominent factors responsible for shaping bacterioplankton composition at the community level (5, 10, 25, 31, 45, 48). However, it is difficult to test hypothesized relationships in complex natural microbial communities (25, 42). In this study, we developed an approach to analyze the complex interactions of three bacterial strains subjected to defined levels of bacterial mortality sources (Fig. 2).

At the end of the experiment (t85), we calculated the proportion of cells surviving in the presence of the flagellate as the percentage of maximum abundance achieved in the flagellate-amended treatments. This parameter differed markedly between the bacterial strains studied (range of 0.1 to 0.5% for FL, 1.5 to 8% for D5, and 25 to 45% for B4) (Fig. 3). Obviously, the selective flagellate grazing predominantly affected the low FL survival rate. Thus, we found, not surprisingly, that grazing clearly had the strongest influence on abundance. Interestingly, in predator-amended treatments the population size did not show any obvious relationship relative to the presence of live viruses in the treatments except for the most grazing-resistant B4 strain, for which a significant synergistic effect of both mortality factors was detected (Fig. 5C and D). Such an interaction also was indicated by the statistical analyses (Table 1) and previously suggested by several authors (25, 41, 42, 48).

Flagellates ingest viruses, virus-infected cells, and prey, which should reduce the viral impact (2, 48). Interestingly, in this study we observed a decrease of viral particles in the presence of the predators only in heat-inactivated treatments (data not shown). In contrast, no clear trend in viral abundance was obvious in either concentration of live virus treatments during the study period, although host-bacterial abundance dropped remarkably as a consequence of flagellate grazing. Thus, the presence of the flagellates may not always negatively influence viral abundances or the viral effect (Fig. 5C and D, B4 strain). Overall, our data do not show a clear antagonistic but rather a synergistic effect of the presence of a grazer on viral abundance and viral effects. In other studies, the presence of grazers also showed a positive or synergistic effect (41, 42, 48).

The virus-induced mortality of the B4 or FL strain was detectable in predator-free treatments for both basal (Fig. 3 and 4) and 3.5-times-more-concentrated live virus treatments (Fig. 5A and B). This also was indicated by the results of plaque assay on agar plates, which was performed at the end of the experiments. Comparing the predator-free treatments thus allowed a much finer evaluation of the species-specific virus effects. For instance, in the predator-free B4+FL treatments, viruses obviously exerted a stronger effect on FL than B4, and thus a larger proportion of the B4 population survived during the second half of the experiment (Fig. 3B and F). This suggests that either more phages were present for FL or that infection and phage propagation were faster for FL. In all cases, the bacterivore-free D5+FL cocultures showed that the virus-resistant D5 strain numerically outcompeted FL even in the virus-inactivated treatments (Fig. 3). In the live virus treatments, this difference became more dramatic when the FL competitiveness was further subjected to the combined negative effect of grazing and the viral attack of FL. Metabolic and lytic products of FL further utilizable by D5 thus also support the overall enhanced ability of resource competition for D5 versus FL in the medium used (Fig. 3C and G, 6, and 7). The latter phenomenon has been shown for marine systems (23, 24, 27) and could explain the enhanced biomass yield of D5 cocultured with FL (Fig. 7). These data suggest that viruses contribute to the niche separation between bacterial strains.

The negative virus effects commonly observed for both B4 and FL in the absence of predation (Fig. 3F and 6) do not seem to be influenced by B4 and FL competition. However, there was a significant positive effect on FL abundance in the presence of both the flagellate and the viruses (Fig. 6). Previous observations indicate that the addition of both viruses and small flagellate bacterivores stimulated the biomass accumulation of the Flectobacillus group within bacterioplankton, likely profiting from the enhanced mortality of competitors (42, 49).

In contrast, in the D5+FL cocultures only the virus-vulnerable FL exhibited significant negative effects to adding live viruses in the absence of the flagellate (Fig. 3G). A stimulation of D5 in the predator-enriched treatments (Fig. 6) could be a simple consequence of being resistant to the present viruses (or the lack of specific viruses present) and profiting from the lysis products released from the FL cells (23, 24). The absence of viruses specific for D5 also was suggested by the lack of the effect of the virus-sized fraction on D5 in the plaque assays.

Notably, it has been shown that the stimulating effect of grazing on viral infection rates of bacteria was linked to an accelerated growth of certain members in natural bacterial communities (17, 41, 42, 49). In our study, we found a negative effect of the combination of grazing and live viruses on FL abundance (Fig. 6), while under the same circumstances D5 achieved even 100% of the maximum biomass yield (Fig. 7), suggesting that D5 was a stronger competitor for nutrient acquisition than FL. Moreover, one may note the consistently pronounced negative effects of concentrated live virus treatments (Fig. 6 and significant interactions in Table 1), where an increased contact rate likely enhanced the probability of infecting the host cells (5, 48).

Biomass yield of strains related to resource competition.

The maximum biomass yield achieved in the predator-free B4+FL cocultures (Fig. 7) suggests that FL is a better competitor for nutrient acquisition than B4, while the data on cell number increases indicated comparable growth potential for all three strains (Fig. 3). The results of field manipulation experiments (38) have led to the conclusion that the whole R-BT065 cluster is comprised of fast-growing phylotypes with an average doubling time of ∼15 h. Thus, they frequently represent the fastest-growing and metabolically relevant segment of bacterioplankton in lakes (15, 28, 37, 38). The only faster-growing bacterioplankton cells were those targeted by the R-FL615 probe (the genus Flectobacillus), whose doubling time was approximately 6 h (38). Regarding the growth rate and nutrient acquisition data, our experiment (Fig. 3 and 4) thus corroborates conclusions drawn from the field studies.

However, the Poterioochromonas sp. used in our study is a much larger flagellate than the typical planktonic bacterivorous flagellates, and consequently it was able to graze the large FL cells much faster than the smaller B4 and D5 cells. In plankton, however, members of the Flectobacillus genus represent grazing-resistant, filament-forming predation defense specialists (38, 47) in the presence of large numbers of small flagellates. Thus, our data cannot be directly extrapolated to the natural environment. However, regardless of this fact, the competition between D5 and FL (or B4 and FL) highlighted remarkable differences in life strategies of two closely related B4 and D5 strains. For instance, the presence of FL did not reduce biomass yield for D5 in any of the predator-free treatments (Fig. 7), implying that D5 was indeed the more competitive strain. The fact that the growth yield of D5 was even slightly higher than 120% in the predator-free treatments did indicate the D5 could use lysis products or metabolic products from FL, which can increase a pool of dissolved or particulate organic material (23, 24, 27).

Possible niche separation between closely related bacterial genotypes.

It has been reported for representatives of other bacterial phyla that very closely related species can display remarkable differences in their ecophysiologic capabilities (13, 18), or that closely related phylotypes can occur in geographically very distant freshwater habitats (8). However, limited knowledge is available on how the effects of biological factors, such competition and mortality sources, can result in niche separation between two coexisting and closely related strains. Our study demonstrated contrasting ecophysiological capabilities of the B4 and D5 strains (Table 2). B4 displayed smaller cells and showed lower biomass yield than D5 under the same experimental conditions. In addition, B4 appeared significantly more vulnerable to viruses obtained from its native habitat but showed enhanced grazing-resistance that may be related to its smaller cell size. In contrast, the D5 strain had slightly larger cells than B4 and was overly competitive even when cocultured with FL. While D5 did not show detectable vulnerability to the indigenous viruses, it was much less resistant to the flagellate predator than B4. All of these differences in biological interactions, as well as observed metabolic differences (V. Kasalický et al., unpublished) likely resulting in differences in carbon source utilization, indicate the partial separation of the ecological niches of the Limnohabitans strains, which are expected to be of relevance under in situ conditions. The future evolution of ecological traits in the natural populations of the strains may shape the ecological niches of the strains; however, an erosion of the partial niche separation is unlikely, because selection should maintain the partial avoidance of competition.

The killing-the-winner hypothesis is a food web model (46) that assumes trade-offs between competition strategists and defense strategists, where the dominant bacteria (winner) for nutrient acquisition are controlled (killed) by viruses and grazers. These trade-offs result in coexistence. A tentative ranking of the three strains based on different traits, such as growth rate, maximum biomass yield, and resistance against viral infection and grazing, is given in Table 2. While our findings generally agree with the hypothesis mentioned above (46), there also are refinements such as hierarchies within defense and competition strategists.

Acknowledgments

This study was largely supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic under research grant 208/05/0015, awarded to K.Š., by the Academy of Sciences, project no. AV0Z 60170517, and also by project MSM 600 766 5801. The grant KONTAKT, number MEB 060702, supported joint experimental activities of K.Š. and M.W.H., and an ATIPE (CNRS) grant supported M.G.W.

We thank J. Jezbera for valuable comments on earlier versions of the manuscript, A. K. Sharma and J. Dolan for English correction, and P. Šmilauer for consultancy regarding statistical data analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, C., M. Zeder, C. Piccini, D. Conde, and J. Pernthaler. 2009. Ecophysiological differences of betaproteobacterial populations in two hydrochemically distinct compartments of a subtropical lagoon. Environ. Microbiol. 11:867-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettarel, Y., T. Sime-Ngando, M. Bouvy, R. Arfi, and C. Amblard. 2005. Low consumption of virus-sized particles by heterotrophic nanoflagellates in two lakes of the French Massif Central. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 39:205-209. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brussaard, C. P. 2004. Optimization of procedures for counting viruses by flow cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1506-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiler, A., and S. Bertilsson. 2004. Composition of freshwater bacterial communities associated with cyanobacterial blooms in four Swedish lakes. Environ. Microbiol. 6:1228-1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuhrman, J. A. 1999. Marine viruses and their biogeochemical and ecological effects. Nature 399:541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gasol, J. M., and P. A. Del Giorgio. 2000. Using flow cytometry for counting natural planktonic bacteria and understanding the structure of planktonic bacterial communities. Sci. Mar. 64:197-224. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray, N. D., D. Comaskey, I. P. Miskin, R. W. Pickup, K. Suzuki, and I. M. Head. 2004. Adaptation of sympatric Achromatium spp. to different redox conditions as a mechanism for coexistence of functionally similar sulphur bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 6:669-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn, M. W. 2003. Isolation of strains belonging to the cosmopolitan Polynucleobacter necessarius cluster from freshwater habitats located in three climatic zones. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5248-5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahn, M. W., and M. G. Höfle. 1998. Grazing pressure by a bacterivorous flagellate reverses the relative abundance of Comamonas acidovorans PX54 and Vibrio strain CB5 in chemostat cocultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1910-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahn, M. W., and M. G. Höfle. 2001. Grazing of protozoa and its effect on populations of aquatic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35:113-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hahn, M. W., V. Kasalický, J. Jezbera, U. Brandt, J. Jezberová, and K. Šimek. Limnohabitans curvus gen. nov., sp. nov., a planktonic bacterium isolated from a freshwater lake. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Hahn, M. W., E. R. B. Moore, and M. G. Höfle. 1999. Bacterial filament formation, a defense mechanism against flagellate grazing, is growth rate controlled in bacteria of different phyla. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:25-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahn, M. W., and M. Pöckl. 2005. Ecotypes of planktonic actinobacteria with identical 16S rRNA genes adapted to thermal niches in temperate, subtropical, and tropical freshwater habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:766-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hahn, M. W., P. Stadler, Q. L. Wu, and M. Pöckl. 2004. The filtration-acclimatization method for isolation of an important fraction of the not readily cultivable bacteria. J. Microb. Methods 57:379-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horňák, K., J. Jezbera, and K. Šimek. 2008. Impact of Microcystis aeruginosa and flagellates on bacterial growth and activity in a eutrophic reservoir. Aquat. Microbiol. Ecol. 52:107-117. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt, D. E., L. A. David, D. Gevers, S. P. Preheim, E. J. Alm, and M. F. Polz. 2008. Resource partitioning and sympatric differentiation among closely related bacterioplankton. Science 320:1081-1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacquet, S., I. Domaizon, S. Personnic, and T. Sime-Ngando. 2007. Do small grazers influence viral-induced bacterial mortality in Lake Bourget? Fund. Appl. Limnol. 170:125-132. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaspers, E., and J. Overmann. 2004. Ecological significance of microdiversity: identical 16S rRNA gene sequences can be found in bacteria with highly divergent genomes and ecophysiologies. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4831-4839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jezbera, J., K. Horňák, and K. Šimek. 2005. Food selection by bacterivorous protists: insight from the analysis of the food vacuole content by means of fluorescence in situ hybridization. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 52:351-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, Z. I., E. R. Zinser, A. Coe, N. P. McNulty, E. M. S. Woodward, and S. W. Chisholm. 2006. Niche partitioning among Prochlorococcus ecotypes along ocean-scale environmental gradients. Science 311:1737-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lindström, E. S., M. P. Kamst-Van Agterveld, and G. Zwart. 2005. Distribution of typical freshwater bacterial groups is associated with pH, temperature, and lake water retention time. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8201-8206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Middelboe, M., Å. Hagström, N. Blackburn, B. Sinn, U. Fisher, N. H. Borch, J. Pinhassi, K. Simu, and M. G. Lorenz. 2001. Effects of bacteriophages on the population dynamics of four strains of pelagic marine bacteria. Microb. Ecol. 42:395-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middelboe, M., N. O. G. Jørgensen, and N. Kroer. 1996. Effects of viruses on nutrient turnover and growth efficiency of noninfected marine bacterioplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1991-1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Middelboe, M., L. Riemann, G. L. Steward, V. Hansen, and O. Nybroe. 2003. Virus-induced transfer of organic carbon between marine bacteria in a model community. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 33:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miki, T., and S. Jacquet. 2008. Complex interactions in the microbial world: under-explored key links between viruses, bacteria and protozoan grazers in aquatic environments. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 51:195-208. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newton, R. J., S. E. Jones, M. R. Helmus, and K. D. McMahon. 2007. Phylogenetic ecology of the freshwater Actinobacteria acI lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7169-7176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noble, R. T., M. Middelboe, and J. A. Fuhrman. 1999. The effects of viral enrichment on the mortality and growth of heterotrophic bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 18:1-13. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peréz, M. T., and R. Sommaruga. 2006. Differential effect of algal- and soil-derived dissolved organic matter on alpine lake bacterial community composition and activity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51:2527-2537. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pérez, M. T., and R. Sommaruga. 2007. Interactive effects of solar radiation and dissolved organic matter on bacterial activity and community structure. Environ. Microbiol. 9:2200-2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pernthaler, A., J. Pernthaler, and R. Amann. 2002. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and catalyzed reporter deposition for the identification of marine bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:3094-3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pernthaler, J. 2005. Predation on prokaryotes in the water column and its ecological implications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Posch, T., J. Pernthaler, A. Alfreider, and A. Psenner. 1997. Cell-specific respiratory activity of aquatic bacteria studied with the tetrazolium reduction method, Cyto-Clear slides, and image analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:867-873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pradeep Ram, A. S., and T. Sime-Ngando. 2008. Functional responses of prokaryotes and viruses to grazer effects and nutrient additions in freshwater microcosms. ISME J. 2:498-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salcher, M. M., J. Pernthaler, M. Zeder, R. Psenner, and T. Posch. 2008. Spatio-temporal niche separation of planktonic Betaproteobacteria in an oligo-mesotrophic lake. Environ. Microbiol. 10:2074-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schauer, M., J. Jiang, and M. W. Hahn. 2006. Recurrent seasonal variations in abundance and composition of filamentous SOL cluster bacteria (Saprospiraceae, Bacteroidetes) in oligomesotrophic Lake Mondsee (Austria). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4704-4712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sekar, R., A. Pernthaler, J. Pernthaler, F. Warnecke, T. Posch, and R. Amann. 2003. An improved protocol for quantification of freshwater Actinobacteria by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2928-2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Šimek, K., K. Horňák, J. Jezbera, M. Mašín, J. Nedoma, J. M. Gasol, and M. Schauer. 2005. Influence of top-down and bottom-up manipulation on the R-BT065 subcluster of beta-proteobacteria, an abundant group in bacterioplankton of a freshwater reservoir. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:2381-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Šimek, K., K. Horňák, J. Jezbera, J. Nedoma, J. Vrba, V. Straškrabová, M. Macek, J. R. Dolan, and M. W. Hahn. 2006. Maximum growth rates and possible life strategies of different bacterioplankton groups in relation to phosphorus availability in a freshwater reservoir. Environ. Microbiol. 8:1613-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Šimek, K., V. Kasalický, J. Jezbera, J. Jezberová, J. Hejzlar, and M. W. Hahn. 2010. Broad habitat range of the phylogenetically narrow R-BT065 cluster, representing a core group of the betaproteobacterial genus Limnohabitans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:631-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Šimek, K., P. Kojecká, J. Nedoma, P. Hartman, J. Vrba, and J. Dolan. 1999. Shifts in bacterial community composition associated with different microzooplankton size fractions in a eutrophic reservoir. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44:1634-1644. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Šimek, K., J. Pernthaler, M. G. Weinbauer, K. Horňák, J. R. Dolan, J. Nedoma, M. Mašín, and R. Amann. 2001. Changes in bacterial community composition, dynamics, and viral mortality rates associated with enhanced flagellate grazing in a mesoeutrophic reservoir. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2723-2733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Šimek, K., M. G. Weinbauer, K. Horňák, J. Jezbera, J. Nedoma, and J. Dolan. 2007. Grazer and virus-induced mortality of bacterioplankton accelerates development of Flectobacillus populations in a freshwater community. Environ. Microbiol. 9:789-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sime-Ngando, T., and A. S. Pradeep Ram. 2005. Grazer effects on prokaryotes and viruses in a freshwater microcosm experiment. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 41:115-124. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suttle, C. A. 1993. Enumeration and isolation of viruses, p. 121-134. In P. F. Kemp, B. F. Sherr, E. B. Sherr, and J. J. Cole (ed.), Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, FL.

- 45.Suttle, C. A. 2007. Marine viruses—major players in global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:801-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thingstad, T. F., and R. Lignell. 1997. Theoretical models for the control of bacterial growth rate, abundance, diversity and carbon demand. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 13:19-27. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thingstad, F., L. Øvreas, J. K. Egge, T. Løvdal, and M. Heldal. 2005. Use of nonlimiting substrates to increase size; a generic strategy to simultaneously optimize uptake and minimize predation in pelagic osmotrophs? Ecol. Lett. 8:675-682. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weinbauer, M. 2004. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 28:127-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinbauer, M., K. Horňák, J. Jezbera, J. Nedoma, J. Dolan, and K. Šimek. 2007. Synergistic and antagonistic effects of viral lysis and protistan grazing on bacterial biomass, production and diversity. Environ. Microbiol. 9:777-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwart, G., B. C. Crump, M. Agterveld, F. Hagen, and S. K. Han. 2002. Typical freshwater bacteria: an analysis of available 16S rRNA gene sequences from plankton of lakes and rivers. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 28:141-155. [Google Scholar]