Abstract

Phthalate esters (PEs) are important environmental pollutants. While the biodegradation of the parent compound, phthalate (PTH), is well characterized, the biodegradation of PEs is not well understood. In particular, prior to this study, genes involved in the uptake and hydrolysis of these compounds were not conclusively identified. We found that Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 could grow on a variety of monoalkyl PEs, including methyl, butyl, hexyl, and 2-ethylhexyl PTHs. Strain RHA1 could not grow on most dialkyl PEs, but suspensions of cells grown on PTH transformed dimethyl, diethyl, dipropyl, dibutyl, dihexyl and di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTHs. The major products of these dialkyl PEs were PTH and the corresponding monoalkyl PEs, and minor products resulted from the shortening of the alkyl side chains. RHA1 exhibited an inducible, ATP-dependent uptake system for PTH with a Km of 22 μM. The deletion and complementation of the patB gene demonstrated that the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter encoded by patDABC is required for the uptake of PTH and monoalkyl PEs by RHA1. The hydrolase encoded by patE of RHA1 was expressed in Escherichia coli. PatE specifically hydrolyzed monoalkyl PEs to PTH but did not transform dialkyl PEs or other aromatic esters. This investigation of RHA1 elucidates key processes that are consistent with the environmental fate of PEs.

Phthalate esters (PEs) used as plasticizers are widespread and toxicologically significant environmental pollutants (35, 52). After a half century of apparently safe use, several environmental and health groups around the world recently have expressed deep concern over the adverse effects of phthalate (PTH) and PEs on ecological systems and human health. PEs have emerged as important pollutants in environmental samples, because they are endocrine-disrupting chemicals with binding activity for the estrogen receptor (25, 37). These compounds are able to induce hepatic peroxisome proliferation, hormonal disorders, reproductive toxicity, and hepatocellular tumors (13, 17, 27, 28). Moreover, attention has been turned to the low-dose toxicity of PEs during crucial windows of fetal development. This recent understanding has fundamentally changed the perception of environmental and health risks of PEs and has made their environmental fate an important issue.

The metabolism of PEs by bacteria is considered a major fate of these widespread pollutants. Substantial evidence exists for PE biodegradation in poorly characterized biological systems, including aquatic, wastewater, and soil systems that are both aerobic and anaerobic (53). Mechanisms for the biodegradation of the parent compounds, the isomers of PTH, are well characterized (7, 11, 19, 24, 39, 47, 50, 55). But despite our knowledge of PTH degradation, mechanisms for the degradation of PEs remain poorly understood. PEs generally are believed to be degraded in natural environments via hydrolysis to the corresponding PTH parent compounds (53). Supporting a degradation mechanism of sequential hydrolysis, several studies have identified pure cultures that degrade dialkyl PEs and have identified only the corresponding monoalkyl PEs and PTH as metabolites occurring prior to ring cleavage (9, 20, 22, 31, 40, 44, 56). However, evidence also exists for alternative biodegradation mechanisms in natural environments (8). Recently, the purification and characterization of two distinct PE hydrolases in Micrococcus sp. YGJ1 were reported (1, 34). A dialkyl PE hydrolase was shown to hydrolyze one ester bond of PTH diesters, yielding monoalkyl PEs. A monoalkyl PE hydrolase also was shown to hydrolyze the ester bond of PTH monoesters but not to attack dialkyl PEs. Thus, both enzymes were required to degrade dialkyl PEs. However, no studies have identified the genes or protein sequences of any confirmed PE hydrolase, preventing a more detailed analysis of these enzymes.

Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 originally was isolated from γ-hexachlorocyclohexane-contaminated soil and is one of the best-characterized polychlorinated biphenyl degraders (21, 49). The sequence of its 9.7-Mb genome (36) (http://www.rhodococcus.ca) further indicates the potential ability of RHA1 to degrade a broad range of aromatic compounds. The group of M. Fukuda (29) demonstrated the growth of RHA1 on PTH and terephthalate and identified duplicate clusters of pad genes (encoding the initial steps of PTH degradation) on two large, linear plasmids of RHA1, pRHL1 and pRHL2. Using proteomic analysis, Patrauchan et al. (42) confirmed the involvement of the pad genes in PTH degradation and showed that the intermediates were further degraded via the protocatechuate branch of the β-ketoadipate pathway. The latter study also identified the pat genes, which are adjacent to the pad genes and putatively encode an ABC transporter and an ester hydrolase (Fig. 1). The expression of both the ATPase component of the ABC transporter (PatA) and the hydrolase (PatE) were increased in the cytoplasm of PTH-grown cells relative to those of the control, and it was suggested that these proteins play roles in uptake of PTH and hydrolysis of PEs, respectively. Our previous transcriptomic analysis of RHA1 growing on either PTH or terephthalate revealed that the ABC transporter genes (patDABC) and ester hydrolase gene (patE) were highly upregulated on PTH but not on terephthalate (24), providing further evidence for the role of the ABC transporter in PTH uptake. Prior to the present study, there was no evidence that RHA1 can degrade PEs, but the induction of patE on PTH suggested the hypothesis that the encoded hydrolase is involved in PE degradation.

FIG. 1.

Organization of phthalate and terephthalate degradation gene cluster. RHA1 has two copies of this gene cluster (99% identical nucleotide sequences) on two large, linear plasmids, pRHL1 and pRHL2. The genes encode the following: padAaAbAcAd, phthalate 3,4-dioxygenase; padB, phthalate 3,4-dihydrodiol dehydrogenase; padC, 3,4-dihydroxyphthalate decarboxylase; padR, IclR-type transcriptional regulator; tpaAaAbB, terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase; tpaC, terephthalate 1,2-diohydrodiol dehydrogenase; tpaR, IclR-type transcriptional regulator; patDABC, probable ABC transporter; and patE, putative phthalate ester hydrolase (www.rhodococcus.ca). This study focused on the shaded genes.

In the present study, we addressed the lack of knowledge regarding the bacterial degradation of PEs by testing the ability of RHA1 to grow on and degrade a broad range of PEs and analogous compounds. We determined the ability of RHA1 to catabolize and cometabolize a range of mono- and dialkyl PEs. Using gene knockout analysis, we examined the proposed role of the PatABCD transporter system in PTH and PE uptake, providing some of the first experimental evidence for the role of an ABC transporter in the uptake of aromatic growth substrates. We cloned and expressed PatE to determine its proposed role in PE degradation, providing the first combined genetic and enzymological characterization of a PE hydrolase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, cultures, and DNA manipulations.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 was grown at 30°C in W minimal salt medium (21) containing 20 mM each growth substrate or in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for stock cultures and gene disruption procedures. Cultures were incubated at 30°C with shaking. All of the compounds listed in Fig. 2 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or TCI America (Portland, OR) and were at least 95% pure. These compounds were added to medium from filter-sterilized (0.2-μm-pore-size filter) stock solutions in water adjusted to pH 10 to 11 with NaOH. DNA manipulations were carried out essentially as described elsewhere (5, 46). Stock cultures of RHA1_032 included 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol to maintain pTip-QC1, but this antibiotic was not included in growth assays of this strain. Thiostrepton was not necessary and was not added to induce patB expression in RHA1_032.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| R. jostii | ||

| RHA1 | Wild type; Cmr | 49 |

| RDO5 | Derivative of RHA1 cured of pRHL2; biphenyl−, Kmr | 51 |

| RHA1_006 | Derivative of RD05 with patB replaced by Aprr gene | This study |

| RHA1_032 | Derivative of RHA_006 with pTip-patB | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| BW25113 | K-12 derivative; ΔaraBAD ΔrhaBAD Ampr | 23 |

| DH10B | Host for pUZ8002 and mutagenized fosmid | 23 |

| BL21(DE3) | hadS gal(λcIts857 indI sam7 nin5 lacUV5-T7 gene1) | 54 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKD46 | λ-Red (gam, bet, exo) araC rep101(Ts) Ampr | 16 |

| pIJ773 | aac(3)IV oriT, source of Aprr cassette | 23 |

| pUC-HY | Source of Hygr gene, Ampr | 32 |

| pUZ8002 | tra neo RP4, Kmr | 23 |

| pET21(+) | Expression vector, Ampr T7 promoter | Novagen |

| pETPE | pET21(+) with an 835-bp PCR fragment carrying patE | This study |

| RF00129K25 | Fosmid clone carrying patB, Cmr | This study |

| RFPAB | RF00129K25 with Cmr replaced with Hygr, Hygr | This study |

| RFHAB | RFCPB with Apar replaced with patB, Hygr Apar | This study |

| pTip-QC1 | Expression vector; Chlrbla PtipArepAB | 38 |

| pTip-patB | pTip-QC1 expressing patB | This study |

FIG. 2.

Structures of compounds used in this study. Underlined compounds were used as growth substrates by RHA1, and the other compounds were not used (n = 3).

Cell suspension assays.

RHA1 was grown on PTH in 10-ml cultures to mid-log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD660] of 1.0). Cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 7,400 × g at 4°C and suspended in 10 ml of fresh W medium plus 1.0 mM the appropriate test substrate in 15-ml tubes. The biomass was approximately 60 μg of protein per ml. Cell suspensions were incubated at 30°C with shaking. Boiled cell suspensions were used as controls.

Analytical methods.

Culture samples (10 ml) and entire cell suspensions (10 ml) were acidified with concentrated HCl and extracted with 10 ml of ethyl acetate. Extracts were derivatized with diazomethane to methylate acid substituents. Samples were analyzed by gas chromatography with an Agilent 6890N chromatograph equipped with an HP-5MS capillary column (30 m by 0.25 mm) and a mass-selective detector. The column temperature was increased initially from 100 to 150°C, and then from 150 to 300°C, at rates of 20 and 3°C per min, respectively. The injector and detector were 220 and 300°C, respectively. Analyte identification was confirmed on the basis of mass spectra from authentic standards and from the National Institute of Standards and Technology MS Search (2.0).

Gene disruption.

The patB::apr mutant (RHA1_006) was constructed using Fosmid RF00129K25 and the λRed system with slight modifications (42). The patB gene was replaced in strain RDO5, a derivative of RHA1 without pRHL2, by an amplicon containing an apramycin resistance gene flanked by the same sequences that flank the patB gene, amplified with the primers PATBfor1 (AGAGGCCGCTAAGACACTGGGGCACGGGACGGATGCCGCATTCCGGGGATCCGTCGACC) and PATBrev1 (TGCTTCACCTTCGGTTCCGGCGCTGAGCGTGGTGGCGTTTGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC).

Phthalate uptake assay.

Phthalate uptake was measured in resting cell suspensions. Cells were grown to mid-log phase on pyruvate, induced by adding 1.0 mM phthalate and incubated for 2 h, washed twice, and suspended at a cell density of 900 mg of protein/liter (OD600 = 13.3) in W medium. Aliquots of 0.05 ml W-medium were placed in 4-ml vials, and ring-UL-[14C]phthalic acid (12.6 mCi/mmol; Sigma-Aldrich, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) was added from an aqueous stock solution. Assays were initiated by adding aliquots of 0.05 ml of cell suspensions to the vials for a final cell density of 450 mg of protein/liter. The vials were incubated with shaking for 5 min at room temperature. Phthalate uptake was stopped by diluting the suspensions with 1.0 ml of ice-cold buffer, collecting the cells on a 0.22-μm-pore-size Millipore GSWP nitrocellulose filter (Fisher Scientific, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada), and washing the cells with 10 ml of 5% Tween-20 (Fisher), then with 10 ml of 50% ethanol, and finally with 10 ml 5% Tween-20. Phase-contrast microscopy indicated that this extensive washing treatment did not lyse the cells. The filters were placed in Beckman Ready-Safe scintillation cocktail (Beckman Coulter, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and counted in a Beckman LS-600IC scintillation counter to determine the amount of phthalate taken up by the cells. The rate of uptake was found to be constant for greater than 5 min, and there was a linear relationship between uptake rate and cell density over a range of 200 to 800 mg of protein/liter. Where indicated, sodium azide, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCCD), or sodium orthovanadate was added to cell suspensions 10 min prior to the addition of the labeled substrate. Steady-state kinetic parameters were analyzed using the least-squares and dynamic weighting options of LEONORA (15).

PatE expression.

To overexpress the patE gene, its coding region was amplified by PCR using RHA1 genomic DNA as a template and the primers patEF (GGAGGACACATATGAGCGC) and patER (CTGGCAATGAAGCTTTCAGC), and it was ligated into pET21(+). The resulting plasmid, pETPE, was used to transform Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). The transformant was grown on LB plus 100 mg/liter ampicillin to an OD660 of 0.5, at which time 1.0 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce patE expression. After 4 h of induction, cells were harvested by centrifugation and sonicated in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The cell lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. Streptomycin (final concentration, 1%) was added to the supernatant, and it was again centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min to remove nucleic acids. Reaction mixtures were in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) with 10 mM substrate. Reactions were started by adding 10 μg of protein from the crude extract and were incubated for 1 h at 30°C. Hydrolysis was quantified as the production of the PTH product.

RESULTS

Growth on PEs.

We tested the ability of RHA1 to grow on a broad range of PEs, benzoate esters, and a salicylate ester (Fig. 2). RHA1 grew on a range of monoalkyl PEs, including monomethyl, monobutyl, monohexyl, and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) PTHs. The specific growth rate of RHA1 on PTH was 0.091 h−1, and the rate was not significantly different on the monoalkyl PEs. No metabolites from monoalkyl PEs were detected. RHA1 was unable to grow on any dialkyl PEs. The only exception was di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH, which supported relatively slow growth (0.034 h−1) to a relatively low final optical density, with the incomplete removal of the substrate (42% removal of 10 mM). Despite its ability to grow efficiently on terephthalate (0.13 h−1) and benzoate (0.13 h−1), RHA1 failed to grow on any of the alkyl esters of terephthalate, benzoate, or salicylate. Thus, growth occurred almost exclusively on monoalkyl esters with an ortho carboxy substituent.

Transformation of dialkyl PEs.

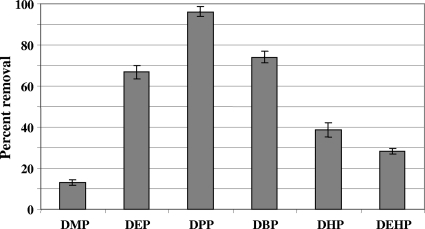

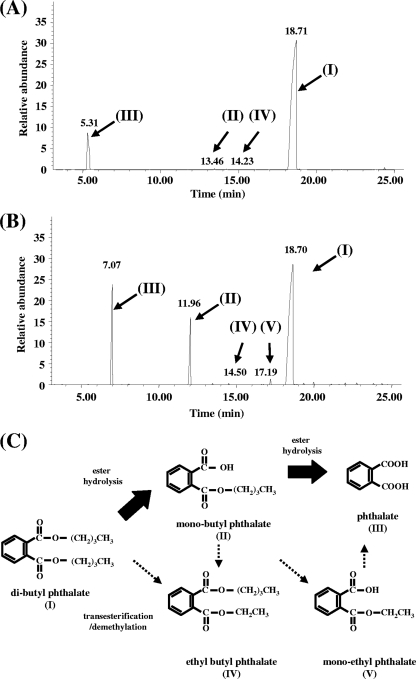

Despite RHA1 being unable to grow on most dialkyl PEs tested, suspensions of cells previously grown on PTH degraded these compounds to various extents, with dipropyl, dibutyl, and diethyl PTH being the most extensively degraded (Fig. 3). In contrast, RHA1 cell suspensions did not remove any of the mono- or dialkyl esters of terephthalate, benzoate, or salicylate that were tested previously as growth substrates (Fig. 2). The removal rates of dialkyl PEs appeared low, as none was completely removed during the 24-h assay. Longer incubations of 72 h were conducted to maximize metabolite formation. The main product detected from dialkyl PEs was PTH, with lesser amounts of the corresponding monoalkyl PE intermediates being detected (Table 2). Additional trace products also were reproducibly formed from each dialkyl PE, indicating that some terminal degradation of the alkyl substituents also occurred. These trace products were not detected as contaminants in the substrates used or in killed controls. The transformation of dibutyl PE (Fig. 4) typifies this general degradation process. The results suggest that the main degradation process is the stepwise hydrolysis of the ester bonds, while the demethylation of the side chains is a concurrent minor process.

FIG. 3.

Relative removal of six phthalate esters by suspensions of RHA1 cells grown on phthalate. The initial concentration of each phthalate ester was 1.0 mM, and cells were incubated for 24 h at 30°C (n = 3; bars indicate standard deviations). DMP, dimethyl phthalate; DEP, diethyl phthalate; DPP, dipropyl phthalate; DBP, dibutyl phthalate; DHP, diheptyl phthalate; DEHP, di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Removal was calculated as a percentage of the residual amounts of phthalate esters in the corresponding boiled control.

TABLE 2.

Metabolite produced from dialkyl PEs by resting cells of RHA1 after 72 h of incubation

| Metabolite detected | Substratea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMP | DEP | DPP | DBP | DHP | DEHP | |

| PTH | 3.24 | 1.81 | 18.2 | 9.05 | 4.15 | 0.094 |

| Monomethyl PTH | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.001 |

| Monoethyl PTH | ND | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| Monopropyl PTH | ND | ND | 0.096 | ND | ND | ND |

| Monobutyl PTH | ND | ND | ND | 0.129 | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| Monoheptyl PTH | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.018 | ND |

| Monoethylhexyl PTH | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.015 |

| Methyl ethyl PTH | ND | 0.002 | 0.085 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Ethyl propyl PTH | ND | ND | 0.065 | 0.018 | 0.021 | 0.007 |

| Ethyl butyl PTH | ND | ND | ND | 0.127 | ND | ND |

Values are mean percentages of total ion current of the original substrate (n = 3). ND, not detected. Other abbreviations are as described in the legend to Fig. 3.

FIG. 4.

Identification of products from dibutyl phthalate degradation by resting cells of RHA1. (A) Gas chromatogram of underivatized products (note that underivatized PTH forms phthalic anhydride, which is the compound that actually accounts for peak III). (B) Gas chromatogram of products derivatized with diazomethane. (C) Proposed pathway for incomplete dibutyl phthalate degradation by RHA1. Analogous pathways are proposed for the five additional dialkyl PEs depicted in Fig. 3 on the basis of metabolites identified in Table 2.

Catalytic activity of PatE.

The patE gene of RHA1 was cloned and expressed in E. coli to determine whether it encodes a PE hydrolase, as hypothesized previously (24, 42). The production of a predominant 23-kDa protein was observed by SDS-PAGE (data not shown), which corresponded reasonably well to the calculated PatE molecular mass of 27 kDa. Crude extracts of E. coli expressing PatE hydrolyzed a range of monoalkyl PEs to PTH (Table 3). No other products were detected in these assays. The negative control, crude extract of E. coli harboring pET21(+), had no hydrolase activity on any substrate tested. The crude extract with PatE failed to hydrolyze the other compounds previously tested as growth substrates, which included dialkyl PEs, mono- and dialkyl terephthalate esters, alkyl benzoate esters, and n-propyl salicylate (Fig. 3). Thus, PatE is a PE hydrolase specific for monoalkyl PEs.

TABLE 3.

Hydrolysis of monoalkyl PEs to PTH by crude extract of E. coli expressing PatE

| Substrate | Sp act ± SD (μmol/min/mg of protein; n = 3) |

|---|---|

| Monomethyl PTH | 14.8 ± 1.33 |

| Monobutyl PTH | 15.3 ± 0.99 |

| Monohexyl PTH | 10.3 ± 0.67 |

| Mono-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH | 9.17 ± 0.73 |

ABC transporter.

Bioinformatic analysis with the NCBI Conserved Domains database (33) confirmed that the patDABC genes encode an ABC transport system. PatA was predicted (expect 5e-86) to contain conserved domain cd03293, the ATP-binding subunit of the bacterial ABC-type nitrate and sulfonate transport systems. This is the most conserved subunit of ABC transport systems and, thus, is the most diagnostic. All of the expected features of this subunit, Q-loop, H-loop/switch region, Walker A motif/P-loop, and Walker B motif, were found in PatA. Thus, PatA is the cytoplasmic ATP-binding component of an ABC transporter. PatB and PatC both were predicted (6e-24 and 6e-29, respectively) to include superfamily cl00427, a binding protein-dependent transport system inner membrane component. This conserved domain includes a putative cytoplasmic loop between two transmembrane domains. For both PatB and PatC, the greatest similarity within this superfamily was to COG0600, the permease component of ABC-type nitrate/sulfonate/bicarbonate transport systems. Thus, PatB and PatC are membrane-spanning permease components of an ABC transporter. PatD was predicted (7e-23) to belong to superfamily cl00115, membrane-associated, periplasmic substrate-binding proteins. Based on this sequence similarity and the location of patD in the putative patDABCE operon (24), PatD is the extracytoplasmic substrate-binding component of an ABC transporter. While the bioinformatic analysis clearly indicated that patDABC encode an ABC transporter, predicted proteins did not have sufficient similarity to functionally characterized orthologs to predict the substrate of the transporter.

The patB gene of RHA1 was disrupted to determine whether it encodes the permease component of an ABC transporter involved in PTH and PE transport, as previously hypothesized (24, 42). Because RHA1 has two 100% identical copies of the patDABCE genes on the megaplasmids pRHL1 and pRHL2, patB was disrupted in strain RDO5, a derivative of RHA1 without pRHL2. Unlike RDO5, the patB mutant strain, RHA1_006, was unable to grow on PTH, monomethyl PTH, monobutyl PTH, and monohexyl PTH. The patB mutation was complemented by transforming RHA1_006 with pTip-patB, which restored the ability to grow on PTH as well as on monomethyl PTH, monobutyl PTH, and monohexyl PTH.

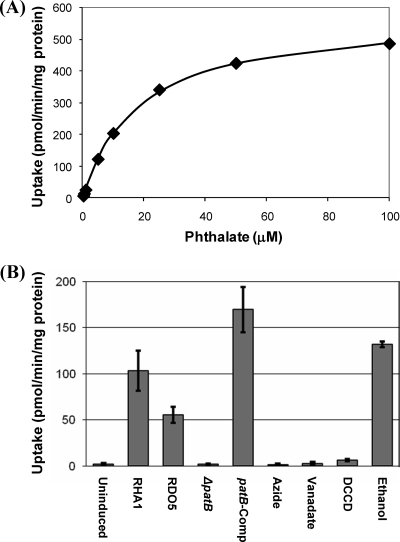

We also directly tested the effect of patB disruption on PTH uptake. Wild-type RHA1 efficiently took up PTH according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Fig. 5). Estimated kinetic constants were Km = 21.7 ± 7.2 μM and Vmax = 606 ± 178 pmol/min/mg of protein (values are means ± standard deviations; n = 4). Uptake activity required prior induction with PTH. The disruption of patB completely abolished PTH uptake activity. Complementation with patB restored uptake activity.

FIG. 5.

Uptake of phthalate. (A) Kinetics of uptake of phthalate by wild-type RHA1. Data are from a representative experiment with the curve indicating the fitted Michaelis-Menten equation. (B) Effects of induction, patE disruption, and inhibitors on uptake activity. Uninduced, wild-type RHA1 not incubated with phthalate prior to the assay (all other treatments were induced); induced, RHA1; patB, patB::apr replacement mutant; azide, RHA1 preincubated with 100 mM sodium azide; vanadate, RHA1 preincubated with 10 mM sodium orthovanadate; DCCD, RHA1 preincubated with 50 mM DCCD plus 430 mM ethanol; ethanol, RHA1 preincubated with 430 mM ethanol; n ≥ 3; error bars indicate standard deviations.

The inhibitors, azide, vanadate and DCCD, all abolished PTH uptake by RHA1 (Fig. 5), providing further evidence that uptake is via an ABC transporter. Azide is an inhibitor of cytochrome c oxidase, so its effect suggests that uptake is energy dependent. Vanadate and DCCD both inhibit proton-driven ATPases via distinct mechanisms, preventing cells from replenishing their ATP pool. The common effect of both ATPase inhibitors strongly suggests that uptake is ATP dependent.

The bioinformatic analysis described above, the effects of patB disruption on growth and uptake, and the effects of inhibitors on uptake, as well as the previous observations during the growth of RHA1 on PTH of the upregulation of the pat genes (24) and the increased expression of PatA (42), all support the conclusion that PTH is taken up by RHA1 via an ABC transport system encoded by patDABC. The growth phenotype of the patB mutant further indicates that this system also is responsible for the uptake of monoalkyl PEs.

DISCUSSION

Cometabolism of dialkyl PEs.

The transformation of dialkyl PEs does not appear to be physiologically important to RHA1. The extent to which such fortuitous transformations contribute to the environmental fate of dialkyl PEs is unclear, but the degradation processes observed in this study can account for most reported biotransformations of PEs in natural environments. Three PEs, dimethyl, diethyl, and dibutyl PTH, are the ones most commonly occurring in the environment and the ones whose biodegradation is best studied. The proposed sequential hydrolysis of these compounds to PTH by RHA1 (Fig. 4) is consistent with the above-described observations in biologically undefined environmental systems and pure cultures. Like RHA1, some other organisms seem limited to the transformation of dialkyl PEs without concomitant growth. A Rhodococcus rhodochrous strain was found to degrade di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH or di-(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate only in the presence of a cosubstrate, such as hexadecane (40). In another study, dimethyl PTH and dimethyl terephthalate were found to support the growth of defined cocultures, but the individual strains could not grow on those compounds (22). However, several isolates are unlike RHA1 and are able to grow on dialkyl PEs (1, 9, 20, 44, 56) or dimethyl terephthalate (30).

Cartwright et al. (8) reported a novel degradation pathway in soil in which diethyl PTH was transformed via ester hydrolysis to monoethyl PTH and also probably via demethylation to ethylmethyl PTH, dimethyl PTH, and monomethyl PTH. Such demethylations are consistent with our detection of the minor metabolites ethyl butyl PTH and monoethyl PTH from dibutyl PTH (Fig. 4) and of analogous minor metabolites from other dialkyl PEs (Table 2). Thus, RHA1 is capable of transformations that can account for the observed shortening of dialkyl PE side chains in natural environments, and RHA1 demonstrates that these transformations can occur with a range of chain lengths. There is not yet any evidence that these chain-shortening transformations can support the growth of any organism.

It is unclear why the PTH that accumulates during dialkyl PE metabolism by RHA1 fails to support growth. One possible explanation that is consistent with our results is that certain dialkyl PEs inhibit the PTH dioxygenase system, thus preventing the initial step in PTH catabolism. Consistently with this possibility, RHA1 failed to grow on PTH when diethyl PTH also was present in the medium. RHA1 grew and degraded PTH in the presence of either diheptyl PTH or di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH, so neither of these compounds with longer alkyl chains directly inhibits PTH degradation. However, diethyl PTH and other dialkyl PEs with shorter alkyl chains were among the trace metabolites formed by RHA1 from both diheptyl PTH or di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH. The accumulation of these metabolites might be inhibitory and might explain the inability of RHA1 to grow on diheptyl PTH and its poor growth on di-(2-ethylhexyl) PTH. Further work is required to conclusively demonstrate any inhibitory effects of dialkyl PEs.

Current understanding of PE hydrolases.

PatE appears to be similar to the only previously characterized monoalkyl PE hydrolase, which is from Micrococcus sp. YGJ1 (34). Although the complete amino acid sequence of monoalkyl PE hydrolase from YGJ1 is not known, its N-terminal amino acid sequence is very similar to that of PatE (14 of 20 similar residues). Further, the measured molecular mass of the YGJ1 enzyme, 27 kDa, is similar to our measured molecular mass of PatE using SDS-PAGE. The available evidence suggests similar substrate specificity of the monoalkyl PTH hydrolase from YGJ1 and PatE, but the former has not been tested on the same range of substrates as the latter, so there may be substantial differences in the specificity of the two enzymes. Arthrobacter keyseri 12B has a gene, pehA, that encodes an amino acid sequence 80% similar to that of PatE (19). Although there is no biochemical evidence for the activity of PehA, it was hypothesized to encode a PE hydrolase, and our results support that hypothesis. It thus appears that PatE and PehA are members of a family of monoalkyl PE hydrolases.

The only other characterized PE hydrolase also is from Micrococcus sp. YGJ1 (1) and specifically attacks dialkyl PEs, leaving monoalkyl PE products. Together, the mono- and dialkyl PTH hydrolases account for the ability of YGJ1 to grow on dialkyl PEs. Interestingly, RHA1 may have a homolog of dialkyl PTH from YGJ1. Again, the complete amino acid sequence of the YGJ1 enzyme is not known, but its N-terminal amino acid sequence is very similar to that of the transcribed protein encoded by the RHA1 gene, ro00365 (10 of 10 similar residues), annotated as a possible hydrolase. Based on enzyme assays, the dialkyl PE hydrolase of YGJ1 was proposed to be constitutively expressed (1), while the monoalkyl PE hydrolase was inducibly expressed (34). This pattern of expression is consistent with the observations that, in RHA1, PTH induces PatE (42) and patE (24). Also consistently, it appears that ro00365 is constitutively expressed, based on the uniformly high signal intensity for its probe relative to those of other probes in a transcriptomic analysis of RHA1 grown on PTH, terephthalate, and pyruvate (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GEO Series accession number GSE6685). Thus, the enzyme encoded by ro00365 may contribute to the observed transformation of dialkyl PEs by RHA1 (Fig. 3 and 4).

A novel ABC transporter.

Bacterial transporter-mediated uptake has been demonstrated for a variety of aromatic substrates, including benzoate (14), 4-hydroxybenzoate (3, 18), protocatechuate (26), phenylacetate (48), 4-hydroxyphenylacetate (3, 43), and PTH (10). Most known transport systems for aromatic compounds are major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters, which are encoded by single genes. The MFS is the largest group of ion-coupled transporters found in all three kingdoms of living organisms (41). The only previously reported transport systems for PTH are the MFS-type permeases from Burkholderia strains (10, 45). The ABC superfamily is the largest and most diverse class of ATP-powered transporters and contains both uptake and efflux transport systems. Members of the ABC superfamily are multicomponent, primary active transporters capable of transporting both small molecules and macromolecules in response to ATP hydrolysis. Until recently, these uptake systems were not known to function in the uptake of aromatic substrates. Recent studies have indicated roles for ABC transporters in the uptake of 3-hydroxyphenyl acetate by Pseudomonas putida (4) and the uptake of the aromatic heterocyclic compound 3-hydroxy-4-pyridone by Rhizobium sp. TAL1145 (6). A 4-hydroxybenzoate transport system in Acinetobacter sp. has not been genetically characterized but is driven by ATP hydrolysis (2), indicating that it could belong to the ABC superfamily. The PatDABC proteins have greatest known similarity to proteins encoded by genes linked to PTH degradation genes in Rhodococcus sp. DK17 (12) and Arthrobacter keyseri (19). Thus, it appears likely that these other Gram-positive bacteria also use this ABC transporter system for the uptake of PTH.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bhanu Ganesh and Manisha Dosanjh for technical assistance, Clinton Fernandes and Matt Myhre for bioinformatic assistance, Katharine Yam for assistance with LEONORA, Yuki Atago for help in the construction of pTip-patB, and Masao Fukuda, Lindsay Eltis, and Julian Davies for helpful discussions. We are grateful to Tomohiro Tamura for providing pTip-QC1.

This work was supported by a grant from Genome Canada/Genome BC.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 28 December 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akita, K., C. Naitou, and K. Maruyama. 2001. Purification and characterization of an esterase from Micrococcus sp. YGJ1 hydrolyzing phthalate esters. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 65:1680-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allende, J. L., A. Gibello, A. Fortun, G. Mengs, E. Ferrer, and M. Martin. 2000. 4-Hydroxybenzoate uptake in an isolated soil Acinetobacter sp. Curr. Microbiol. 40:34-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allende, J. L., A. Gibello, M. Martin, and A. Garrido-Pertierra. 1992. Transport of 4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 292:583-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arias-Barrau, E., A. Sandoval, G. Naharro, E. R. Olivera, and J. M. Luengo. 2005. A two-component hydroxylase involved in the assimilation of 3-hydroxyphenyl acetate in Pseudomonas putida. J. Biol. Chem. 280:26435-26447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1990. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 6.Awaya, J. D., P. M. Fox, and D. Borthakur. 2005. pyd genes of Rhizobium sp. strain TAL1145 are required for degradation of 3-hydroxy-4-pyridone, an aromatic intermediate in mimosine metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 187:4480-4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batie, C. J., E. LaHaie, and D. P. Ballou. 1987. Purification and characterization of phthalate oxygenase and phthalate oxygenase reductase from Pseudomonas cepacia. J. Biol. Chem. 262:1510-1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cartwright, C. D., S. A. Owen, I. P. Thompson, and R. G. Burns. 2000. Biodegradation of diethyl phthalate in soil by a novel pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186:27-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang, B. V., C. M. Yang, C. H. Cheng, and S. Y. Yuan. 2004. Biodegradation of phthalate esters by two bacteria strains. Chemosphere 55:533-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, H. K., and G. J. Zylstra. 1999. Characterization of the phthalate permease OphD from Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 17616. J. Bacteriol. 181:6197-6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, H. K., and G. J. Zylstra. 1998. Novel organization of the genes for phthalate degradation from Burkholderia cepacia DBO1. J. Bacteriol. 180:6529-6537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi, K. Y., D. Kim, W. J. Sul, J. C. Chae, G. J. Zylstra, Y. M. Kim, and E. Kim. 2005. Molecular and biochemical analysis of phthalate and terephthalate degradation by Rhodococcus sp. strain DK17. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252:207-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colborn, T., F. S. vom Saal, and A. M. Soto. 1993. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 101:378-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collier, L. S., N. N. Nichols, and E. L. Neidle. 1997. benK encodes a hydrophobic permease-like protein involved in benzoate degradation by Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1. J. Bacteriol. 179:5943-5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornish-Bowden, A. 1995. Analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- 16.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.David, R. M., M. R. Moore, M. A. Cifone, D. C. Finney, and D. Guest. 1999. Chronic peroxisome proliferation and hepatomegaly associated with the hepatocellular tumorigenesis of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and the effects of recovery. Toxicol. Sci. 50:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditty, J. L., and C. S. Harwood. 2002. Charged amino acids conserved in the aromatic acid/H+ symporter family of permeases are required for 4-hydroxybenzoate transport by PcaK from Pseudomonas putida. J. Bacteriol. 184:1444-1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eaton, R. W. 2001. Plasmid-encoded phthalate catabolic pathway in Arthrobacter keyseri 12B. J. Bacteriol. 183:3689-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton, R. W., and D. W. Ribbons. 1982. Metabolism of dibutylphthalate and phthalate by Micrococcus sp. strain 12B. J. Bacteriol. 151:48-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuda, M., S. Shimizu, N. Okita, M. Seto, and E. Masai. 1998. Structural alteration of linear plasmids encoding the genes for polychlorinated biphenyl degradation in Rhodococcus strain RHA1. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 74:169-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gu, J. D., J. Li, and Y. Wang. 2005. Biochemical pathway and degradation of phthalate ester isomers by bacteria. Water Sci. Technol. 52:241-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara, H., L. E. Eltis, J. E. Davies, and W. W. Mohn. 2007. Transcriptomic analysis reveals a bifurcated terephthalate degradation pathway in Rhodococcus sp. RHA1. J. Bacteriol. 189:1641-1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris, C. A., P. Henttu, M. G. Parker, and J. P. Sumpter. 1997. The estrogenic activity of phthalate esters in vitro. Environ. Health Perspect. 105:802-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harwood, C. S., and R. E. Parales. 1996. The beta-ketoadipate pathway and the biology of self-identity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:553-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huff, J. E., and W. M. Kluwe. 1984. Phthalate esters carcinogenicity in F344/N rats and B6C3F1 mice. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 141:137-154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jobling, S., T. Reynolds, R. White, M. G. Parker, and J. P. Sumpter. 1995. A variety of environmentally persistent chemicals, including some phthalate plasticizers, are weakly estrogenic. Environ. Health Perspect. 103:582-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitagawa, W. 2001. Ph.D. thesis. Nagaoka University of Technology, Nagaoka, Japan.

- 30.Li, J., and J. D. Gu. 2006. Biodegradation of dimethyl terephthalate by Pasteurella multocida Sa follows an alternative biochemical pathway. Ecotoxicology 15:391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li, J. X., J. D. Gu, and L. Pan. 2005. Transformation of dimethyl phthalate, dimethyl isophthalate and dimethyl terephthalate by Rhodococcus ruber Sa and modeling the processes using the modified Gompertz model. Intl. Biodeter. Biodeg. 55:223-232. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahenthiralingam, E., B. I. Marklund, L. A. Brooks, D. A. Smith, G. J. Bancroft, and R. W. Stokes. 1998. Site-directed mutagenesis of the 19-kilodalton lipoprotein antigen reveals No essential role for the protein in the growth and virulence of Mycobacterium intracellulare. Infect. Immun. 66:3626-3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchler-Bauer, A., J. B. Anderson, M. K. Derbyshire, C. DeWeese-Scott, N. R. Gonzales, M. Gwadz, L. Hao, S. He, D. I. Hurwitz, J. D. Jackson, Z. Ke, D. Krylov, C. J. Lanczycki, C. A. Liebert, C. Liu, F. Lu, S. Lu, G. H. Marchler, M. Mullokandov, J. S. Song, N. Thanki, R. A. Yamashita, J. J. Yin, D. Zhang, and S. H. Bryant. 2007. CDD: a conserved domain database for interactive domain family analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 35:D237-D240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maruyama, K., K. Akita, C. Naitou, M. Yoshida, and T. Kitamura. 2005. Purification and characterization of an esterase hydrolyzing monoalkyl phthalates from Micrococcus sp. YGJ1. J. Biochem. 137:27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayer, F. L., D. L. Stalling, and J. L. Johnson. 1972. Phthalate esters as environmental contaminants. Nature 238:411-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McLeod, M. M., R. L. Warren, W. W. L. Hsiao, N. Araki, M. Myhre, C. Fernandes, D. Miyazawa, W. Wong, A. L. Lillquist, D. Wang, M. Dosanjh, H. Hara, A. Petrescu, R. D. Morin, G. Yang, J. M. Stott, J. E. Schein, H. Shin, D. Smailus, A. S. Siddiqui, M. A. Marra, S. J. M. Jones, R. Holt, F. S. L. Brinkman, K. Miyauchi, M. Fukuda, J. E. Davies, W. W. Mohn, and L. D. Eltis. 2006. The complete genome of Rhodococcus sp. RHA1 provides insights into a catabolic powerhouse. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:15582-15587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakai, M., Y. Tabira, D. Asai, Y. Yakabe, T. Shimyozu, M. Noguchi, M. Takatsuki, and Y. Shimohigashi. 1999. Binding characteristics of dialkyl phthalates for the estrogen receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 254:311-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakashima, N., and T. Tamura. 2004. Isolation and characterization of a rolling-circle-type plasmid from Rhodococcus erythropolis and application of the plasmid to multiple-recombinant-protein expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:5557-5568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakazawa, T., and E. Hayashi. 1977. Phthalate metabolism in Pseudomonas testosteroni: accumulation of 4,5-dihydroxyphthalate by a mutant strain. J. Bacteriol. 131:42-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nallii, S., D. G. Cooper, and J. A. Nicell. 2002. Biodegradation of plasticizers by Rhodococcus rhodochrous. Biodegradation 13:343-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pao, S. S., I. T. Paulsen, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 1998. Major facilitator superfamily. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patrauchan, M. A., C. Florizone, M. Dosanjh, W. W. Mohn, J. Davies, and L. D. Eltis. 2005. Catabolism of benzoate and phthalate in Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1: redundancies and convergence. J. Bacteriol. 187:4050-4063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prieto, M. A., and J. L. Garcia. 1997. Identification of the 4-hydroxyphenylacetate transport gene of Escherichia coli W: construction of a highly sensitive cellular biosensor. FEBS Lett. 414:293-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quan, C. S., Q. Liu, W. J. Tian, J. Kikuchi, and S. D. Fan. 2005. Biodegradation of an endocrine-disrupting chemical, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, by Bacillus subtilis no. 66. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 66:702-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saint, C. P., and P. Romas. 1996. 4-Methylphthalate catabolism in Burkholderia (Pseudomonas) cepacia Pc701: a gene encoding a phthalate-specific permease forms part of a novel gene cluster. Microbiology 142:2407-2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 47.Schläfli, H. R., M. A. Weiss, T. Leisinger, and A. M. Cook. 1994. Terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase system from Comamonas testosteroni T-2: purification and some properties of the oxygenase component. J. Bacteriol. 176:6644-6652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schleissner, C., E. R. Olivera, M. Fernandez-Valverde, and J. M. Luengo. 1994. Aerobic catabolism of phenylacetic acid in Pseudomonas putida U: biochemical characterization of a specific phenylacetic acid transport system and formal demonstration that phenylacetyl-coenzyme A is a catabolic intermediate. J. Bacteriol. 176:7667-7676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seto, M., K. Kimbara, M. Shimura, T. Hatta, M. Fukuda, and K. Yano. 1995. A novel transformation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3353-3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shigematsu, T., K. Yumihara, Y. Ueda, S. Morimura, and K. Kida. 2003. Purification and gene cloning of the oxygenase component of the terephthalate 1,2-dioxygenase system from Delftia tsuruhatensis strain T7. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220:255-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimizu, S., H. Kobayashi, E. Masai, and M. Fukuda. 2001. Characterization of the 450-kb linear plasmid in a polychlorinated biphenyl degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2021-2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Staples, C. A., T. F. Parkerton, and D. R. Peterson. 2000. A risk assessment of selected phthalate esters in North American and Western European surface waters. Chemosphere 40:885-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Staples, C. A., D. R. Peterson, T. F. Parkerton, and W. J. Adams. 1997. The environmental fate of phthalate esters: a literature review. Chemosphere 35:667-749. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Studier, F. W., and B. A. Moffatt. 1986. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol. 189:113-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang, Y. Z., Y. Zhou, and G. J. Zylstra. 1995. Molecular analysis of isophthalate and terephthalate degradation by Comamonas testosteroni YZW-D. Environ. Health Perspect. 103(Suppl. 5):9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu, X.-R., H.-B. Li, and J.-D. Gu. 2005. Biodegradation of an endocrine-disrupting chemical di-n-butyl phthalate ester by Pseudomonas fluorescens B-1. Intl. Biodeter. Biodeg. 55:9-15. [Google Scholar]