Abstract

Frankia is an actinobacterium that fixes nitrogen under both symbiotic and free-living conditions. We identified genes upregulated in free-living nitrogen-fixing cells by using suppression subtractive hybridization. They included genes with predicted functions related to nitrogen fixation, as well as with unknown function. Their upregulation was a novel finding in Frankia.

Frankia is a Gram-positive actinobacterium that establishes symbiosis with several angiosperms termed actinorhizal plants and forms nitrogen-fixing nodules on their roots (20). Frankia also fixes nitrogen in free-living culture under nitrogen-free conditions (19). Induction of the nitrogen-fixing ability is accompanied by differentiation of vesicles (19). Vesicles are spherical cells specialized to nitrogen fixation and are surrounded by multilayered lipid envelopes by which nitrogenase is protected from oxygen (3). Frankia plays an important role in the global nitrogen cycle, yet little is known about the genes involved in the induction of nitrogen-fixing activity. Recently, three Frankia genome sequences were determined (15), which facilitates the genetic dissection of Frankia biology. In this study, we identified Frankia genes induced in nitrogen-fixing cells under free-living conditions by using suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) (4).

Induction of nitrogen-fixing cells.

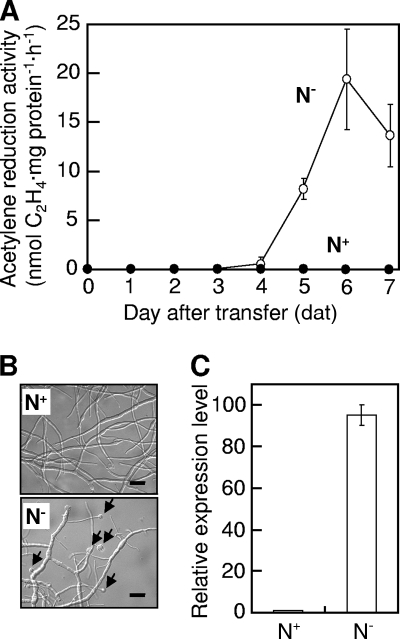

We cultured Frankia sp. strain HFPCcI3 (CcI3) (21) in a modified BAP medium (14) (N+) in which 10 mg/liter FeNa-EDTA was replaced with Fe-citrate, 0.001 mg/liter CoSO4·7H2O was added, biotin was removed, and the pH was adjusted to 6.7, to late log phase at 28°C with a magnetic stirrer bar stirring at 300 rpm. In order to induce nitrogen-fixing ability in CcI3, we washed the cells twice with N+ medium without NH4Cl (N−) and resuspended half of them in N− medium. The remaining half was resuspended in N+ medium as a control. We measured the nitrogen fixation activity of the cells as acetylene reduction activity (ARA) by following the procedure described in reference 14 and using a GC8-AIF gas chromatograph (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). We extracted protein by heating the cells at 90°C for 15 min in 1 N NaOH (18) and normalized ARA to the amount of protein in the cells. Nitrogen fixation activity in Frankia became evident 4 days after transfer (dat) to N− medium and peaked at 6 dat (Fig. 1A, open circles). We detected no nitrogen fixation activity in the cells kept in N+ medium (Fig. 1A, closed circles). At 6 dat in cells grown in N− medium, we observed the presence of vesicles (Fig. 1B). We isolated total RNA from the 6-dat cells by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (12) and analyzed the expression level of the nifH gene encoding dinitrogenase reductase by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR; see Table S1 in the supplemental material for the primers used) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Perfect Real Time; Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) and a 7300 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). We observed drastic upregulation of the nifH gene under the N− condition (Fig. 1C). The results indicate that cells of CcI3 were completely shifted to nitrogen-fixing status at 6 dat to N− medium.

FIG. 1.

Acclimation of Frankia sp. strain CcI3 cells to nitrogen-free conditions shown by the time course of acetylene reduction activity (A), nitrogen fixation vesicle formation (B), and nifH expression (C). (A) Acetylene reduction activity was measured in strain CcI3 grown in BAP medium containing 5 mM NH4Cl (N+, closed circles) or without a nitrogen source (N−, open circles). Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 2). (B) Photomicrographs of the Frankia cells were taken at 6 dat to N+ (top) or N− (bottom) conditions. Arrows indicate vesicles. Bars, 1 μm. (C) qRT-PCR of the nifH gene was performed using total RNA extracted from the cells at 6 dat to N+ or N− conditions. Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3).

SSH using eukaryotic mRNA-like RNA.

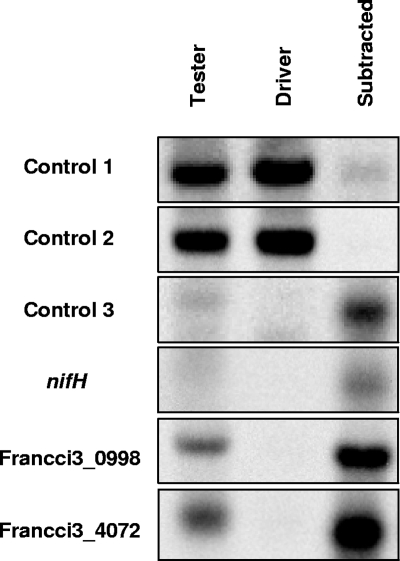

SSH is a powerful tool that can be used to screen differentially expressed genes (4). SSH uses two cDNA samples—a “tester” and a “driver”—and transcripts contained only in the tester are amplified as transcripts common to both the tester and the driver are suppressed. A problem, however, is that the method was designed for eukaryotes (4). To apply SSH to a prokaryote, Frankia, we artificially generated eukaryotic mRNA-like RNA (eml-RNA) from total RNA. We purified mRNA from 20 μg total RNA using a MICROBExpress bacterial mRNA purification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's protocol, repeating the procedure twice, and polyadenylated 1 μg purified mRNA in 25 μl of a solution containing 40 U of poly(A) polymerase (USB, Cleveland, OH), 1× poly(A) polymerase reaction buffer, and 0.5 mM ATP at 37°C for 2 min. We added the three exogenous control RNAs to the polyadenylation reaction mixture (accession numbers: control 1, AB510589; control 2, AB510590; control 3, AB510588), those which were synthesized by in vitro transcription using T3 RNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). We added two control RNAs to the tester and driver mRNAs in equal amounts (control 1 and control 2) that mimicked common transcripts. We also added a control RNA only to the tester mRNA (control 3) that mimicked a transcript expressed specifically in the tester sample. Weight ratios of control RNAs to mRNA were 0.5% for control 1 and 0.05% for control 2 and control 3. The polyadenylated mRNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, chloroform extraction, and 2-propanol precipitation. We synthesized cDNA from the eml-RNA with a cDNA synthesis kit (Moloney murine leukemia virus version; Takara Bio) by using an oligo(dT) primer. Electrophoresis of cDNA showed a smear pattern below about 3 kb (data not shown), indicating that eml-RNA was successfully generated. We amplified the cDNA by PCR prior to SSH according to the procedure described in reference 9. This step enabled us to perform SSH with only ∼100 ng cDNA, which we obtained from a single synthesis reaction. We performed SSH using eml-RNA from N− cells as the tester and that from N+ cells as the driver, essentially by following the procedure described in reference 5. To confirm successful subtraction, Southern blot analysis was performed by using the AlkPhos Direct Labeling and Detection System (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). The signal strengths of the control 1 and control 2 cDNAs were drastically reduced in the subtracted cDNA compared with those of the tester and driver cDNAs (Fig. 2). The signal strength of control 3 cDNA, in contrast, increased in the subtracted cDNA pool (Fig. 2). Moreover, the signal strength in the endogenous Frankia genes (nifH, Francci3_0998 and Francci3_4072), which were specifically expressed in tester RNA, increased similarly (Fig. 2). These results indicate that in the subtracted cDNA pool the transcripts expressed in both the tester and driver samples were suppressed while those expressed only in the tester samples were enriched.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis probed by control cDNA fragments, nifH, Francci3_0998, and Francci3_4072. Tester-specific induction of the Francci3_0998 and Francci3_4072 genes was found in this study (Table 1).

Identification of genes induced in nitrogen-fixing cells.

Subtracted cDNA fragments were cloned into a plasmid vector. We randomly selected 96 clones from the subtracted library for sequencing and identified genes by a BLAST search (2) against the CcI3 genome (15); however, 63 clones contained the 16S or 23S rRNA gene. A mathematical model of SSH shows that abundant transcripts are prone to be detected as false positives even if they are not differentially expressed (7). Our mRNA contained a significant amount of residual rRNA even after purification (data not shown), which is probably why we identified so many rRNA gene clones. Of the remaining 33 clones, 31 contained a coding sequence of a gene (Table 1) and 2 contained an intergenic sequence. We confirmed the expression levels of the 10 genes under N+ and N− conditions by qRT-PCR (see Table S1 in the supplemental material for primers), and 9 (90%) were indeed upregulated in N− cells (Table 1), indicating the reliability of our procedure.

TABLE 1.

Genes identified by SSH in this study

| Genea (no. of clones identified) | Annotationb | Relative expression levelc (N−/N+ ± SD) (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Francci3_0394 (1) | Cupin 4 | NDd |

| Francci3_0586 (1) | Ribosomal protein S19 | ND |

| Francci3_0806 (2) | Hypothetical protein | ND |

| Francci3_0998 (4) | Hypothetical protein | 82.9 ± 10.5 |

| Francci3_0999 (1) | Crotonyl coenzyme A reductase | ND |

| Francci3_1000 (1) | 3-Hydroxyacyl coenzyme A dehydrogenase | 11.6 ± 0.8 |

| Francci3_1277 (1) | Hypothetical protein | ND |

| Francci3_1531 (1) | Hypothetical protein | ND |

| Francci3_1533 (1) | Phosphoenolpyruvate phosphomutase | ND |

| Francci3_1601 (1) | Fibronectin, type III | ND |

| Francci3_1761 (1) | DNA topoisomerase II | ND |

| Francci3_2461 (2) | Nonribosomal peptide synthetase | 14.6 ± 1.1 |

| Francci3_2465 (1) | Hypothetical protein | ND |

| Francci3_2514 (1) | Zinc-binding alcohol dehydrogenase | 4.3 ± 0.2 |

| Francci3_2726 (2) | Hypothetical protein | ND |

| Francci3_2753 (1) | Rhodanese like | 121 ± 11 |

| Francci3_2949 (1) | Catalase | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Francci3_3603 (1) | 50S ribosomal protein L32 | 37.6 ± 8.2 |

| Francci3_4022 (1) | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | ND |

| Francci3_4072 (3) | Hypothetical protein | 1,536 ± 118 |

| Francci3_4255 (1) | CarD family transcriptional regulator | 3.6 ± 0.7 |

| Francci3_4465 (1) | OsmC-like protein | ND |

| Francci3_4489 (1) | Homocitrate synthase (nifV) | 452 ± 21 |

Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (http://genome.jgi-psf.org/fra_c/fra_c.home.html).

National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Determined by qRT-PCR. Normalized by 16S rRNA.

ND, not determined.

Genes identified by SSH contained those whose annotated function was relevant to nitrogen fixation (Table 1). Francci3_4489 showed homology to nifV, which encodes homocitrate synthase in other Frankia strains and in nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria. Homocitrate is a component of nitrogenase FeMo cofactor (8, 10, 13). Francci3_2461 showed homology to an enzyme in Thermobifida fusca, nonribosomal peptide synthetase, which catalyzes the synthesis of a siderophore (6). Siderophores mediate the uptake of Fe and Mo ions, which are required by the nitrogenase complex (11). Francci3_2514 exhibited homology to a putative alcohol dehydrogenase in the rhizobium Bradyrhizobium japonicum, where the gene is upregulated 54.4 times in nitrogen-fixing root nodules compared with free-living cells (16). We found two genes related to energy metabolism processes such as fatty acid beta oxidation (Francci3_1000) and glycolysis (Francci3_4022), one of which was confirmed to be upregulated under the N− condition by qRT-PCR. Activation of these genes is reasonable since nitrogen fixation is a highly energy-consuming reaction (17). We also found two ribosomal protein genes (Francci3_0586 and Francci3_3603) in the subtracted library, one of which was upregulated 37.6 times in the N− cells. Because the onset of nitrogen fixation requires de novo protein synthesis (1), upregulation of translation-related genes would be necessary. In addition, we identified seven hypothetical protein genes with no predicted function. Notably, upregulation of Francci3_4072 was drastic (1,536 times). A homologue of the gene was found only in Frankia alni strain ACN14a, suggesting that the gene plays a unique role in Frankia nitrogen fixation.

Upregulation of those genes was a novel finding in Frankia; none of them were found in the previous proteome analysis (1). For a better understanding of nitrogen fixation, the function of the genes we identified here should be analyzed by disruption by the transformation method currently being developed in our laboratory (12).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Louis Tisa of the University of New Hampshire for the generous gift of Frankia sp. strain CcI3, the Kazusa DNA Research Institute for providing the Lotus japonicus expressed sequence tag clones used for the preparation of control RNA, and Miriam Bloom (SciWrite Biomedical Writing and Editing Services) for professional editing.

This work was supported by grants from the Nissan Science Foundation, The Asahi Glass Foundation, and Kagoshima Kagaku Kenkyuusyo.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 4 January 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloisio, N., S. Felix, J. Marechal, P. Pujic, Z. Rouy, D. Vallenet, C. Medigue, and P. Normand. 2007. Frankia alni proteome under nitrogen-fixing and nitrogen-replete conditions. Physiol. Plant. 130:440-453. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry, A. M., O. T. Harriott, R. A. Moreau, S. F. Osman, D. R. Benson, and A. D. Jones. 1993. Hopanoid lipids compose the Frankia vesicle envelope, presumptive barrier of oxygen diffusion to nitrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:6091-6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diatchenko, L., Y. F. Lau, A. P. Campbell, A. Chenchik, F. Moqadam, B. Huang, S. Lukyanov, K. Lukyanov, N. Gurskaya, E. D. Sverdlov, and P. D. Siebert. 1996. Suppression subtractive hybridization: a method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:6025-6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diatchenko, L., S. Lukyanov, Y. F. Lau, and P. D. Siebert. 1999. Suppression subtractive hybridization: a versatile method for identifying differentially expressed genes. Methods Enzymol. 303:349-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dimise, E. J., P. F. Widboom, and S. D. Bruner. 2008. Structure elucidation and biosynthesis of fuscachelins, peptide siderophores from the moderate thermophile Thermobifida fusca. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:15311-15316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadgil, C., A. Rink, C. Beattie, and W. S. Hu. 2002. A mathematical model for suppression subtractive hybridization. Comp. Funct. Genomics 3:405-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gronberg, K. L. C., C. A. Gormal, M. C. Durrant, B. E. Smith, and R. A. Henderson. 1998. Why R-homocitrate is essential to the reactivity of FeMo-cofactor of nitrogenase: studies on nifV−-extracted FeMo-cofactor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120:10613-10621. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurskaya, N. G., L. Diatchenko, A. Chenchik, P. D. Siebert, G. L. Khaspekov, K. A. Lukyanov, L. L. Vagner, O. D. Ermolaeva, S. A. Lukyanov, and E. D. Sverdlov. 1996. Equalizing cDNA subtraction based on selective suppression of polymerase chain reaction: cloning of Jurkat cell transcripts induced by phytohemagglutinin and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. Anal. Biochem. 240:90-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoover, T. R., J. Imperial, P. W. Ludden, and V. K. Shah. 1989. Homocitrate is a component of the iron-molybdenum cofactor of nitrogenase. Biochemistry 28:2768-2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kraepiel, A., J. Bellenger, T. Wichard, and F. Morel. 2009. Multiple roles of siderophores in free-living nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Biometals 22:573-581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucho, K., K. Kakoi, M. Yamaura, S. Higashi, T. Uchiumi, and M. Abe. 2009. Transient transformation of Frankia by fusion marker genes in liquid culture. Microbe Environ. 24:231-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masukawa, H., K. Inoue, and H. Sakurai. 2007. Effects of disruption of homocitrate synthase genes on Nostoc sp. strain PCC 7120 photobiological hydrogen production and nitrogenase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:7562-7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murry, M., M. Fontaine, and J. Torrey. 1984. Growth kinetics and nitrogenase induction in Frankia sp. HFPArI 3 grown in batch culture. Plant Soil. 78:61-78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Normand, P., P. Lapierre, L. S. Tisa, J. P. Gogarten, N. Alloisio, E. Bagnarol, C. A. Bassi, A. M. Berry, D. M. Bickhart, N. Choisne, A. Couloux, B. Cournoyer, S. Cruveiller, V. Daubin, N. Demange, M. P. Francino, E. Goltsman, Y. Huang, O. R. Kopp, L. Labarre, A. Lapidus, C. Lavire, J. Marechal, M. Martinez, J. E. Mastronunzio, B. C. Mullin, J. Niemann, P. Pujic, T. Rawnsley, Z. Rouy, C. Schenowitz, A. Sellstedt, F. Tavares, J. P. Tomkins, D. Vallenet, C. Valverde, L. G. Wall, Y. Wang, C. Medigue, and D. R. Benson. 2007. Genome characteristics of facultatively symbiotic Frankia sp. strains reflect host range and host plant biogeography. Genome Res. 17:7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pessi, G., C. H. Ahrens, H. Rehrauer, A. Lindemann, F. Hauser, H. M. Fischer, and H. Hennecke. 2007. Genome-wide transcript analysis of Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteroids in soybean root nodules. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 20:1353-1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seefeldt, L. C., B. M. Hoffman, and D. R. Dean. 2009. Mechanism of Mo-dependent nitrogenase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78:701-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tisa, L. S., and J. C. Ensign. 1987. Isolation and nitrogenase activity of vesicles from Frankia sp. strain EAN1pec. J. Bacteriol. 169:5054-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjepkema, J. D., W. Ormerod, and J. G. Torrey. 1980. Vesicle formation and acetylene reduction activity in Frankia sp. CPI1 cultured in defined nutrient media. Nature 287:633-635. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wall, L. G. 2000. The actinorhizal symbiosis. J. Plant Growth Regul. 19:167-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang, Z., M. Lopez, and J. Torrey. 1984. A comparison of cultural characteristics and infectivity of Frankia isolates from root nodules of Casuarina species. Plant Soil 78:79-90. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.