Abstract

To gain insights into the origin and genome evolution of the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis, we have sequenced the deep-rooted strain Angola, a virulent Pestoides isolate. Its ancient nature makes this atypical isolate of particular importance in understanding the evolution of plague pathogenicity. Its chromosome features a unique genetic make-up intermediate between modern Y. pestis isolates and its evolutionary ancestor, Y. pseudotuberculosis. Our genotypic and phenotypic analyses led us to conclude that Angola belongs to one of the most ancient Y. pestis lineages thus far sequenced. The mobilome carries the first reported chimeric plasmid combining the two species-specific virulence plasmids. Genomic findings were validated in virulence assays demonstrating that its pathogenic potential is distinct from modern Y. pestis isolates. Human infection with this particular isolate would not be diagnosed by the standard clinical tests, as Angola lacks the plasmid-borne capsule, and a possible emergence of this genotype raises major public health concerns. To assess the genomic plasticity in Y. pestis, we investigated the global gene reservoir and estimated the pangenome at 4,844 unique protein-coding genes. As shown by the genomic analysis of this evolutionary key isolate, we found that the genomic plasticity within Y. pestis clearly was not as limited as previously thought, which is strengthened by the detection of the largest number of isolate-specific single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) currently reported in the species. This study identified numerous novel genetic signatures, some of which seem to be intimately associated with plague virulence. These markers are valuable in the development of a robust typing system critical for forensic, diagnostic, and epidemiological studies.

Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague, is a nonmotile Gram-negative bacterial pathogen. The genus Yersinia comprises two other pathogens that cause worldwide infections in humans and animals: Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica (11, 12, 22, 61, 71). Despite their genetic relationship, these species differ radically in their pathogenicity and transmission. Plague is primarily a disease of wild rodents that is transmitted to other mammals through flea bites. In humans it produces the bubonic form of plague. Y. pestis also can be transmitted from human to human by aerosol, especially during pandemics, causing primarily pneumonic plague. Evolutionarily, it is estimated that Y. pestis diverged from the enteric pathogen Y. pseudotuberculosis within the last 20,000 years, while Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica lineages separated 0.4 to 1.9 million years ago (2). Y. pestis inhabits a distinct ecological niche, and its transmission is anchored in its unique plasmid inventory: the murine toxin (pMT) and plasminogen activator (pPCP) plasmids. In addition, Y. pestis harbors the low-calcium-response plasmid pCD, which it inherited from its closest relative, Y. pseudotuberculosis (pYV) (12), and it also is found in the more distantly related Y. enterocolitica (71). So-called cryptic plasmids have been described in the literature as part of the Y. pestis mobilome (71), but no sequence data are available to decipher the nature and impact of such plasmids in the epidemiology and pathogenicity of Y. pestis (14). Y. pestis isolates have been historically grouped into the biovars Antiqua (ANT), Medievalis (MED), and Orientalis (ORI), based on metabolic properties such as nitrate reduction and fermentation patterns (72). However, we will use the population-based nomenclature for Y. pestis introduced by Achtman et al. (1), as we believe it better reflects the true evolutionary relationship. Due to its young evolutionary age, only a few genetic polymorphisms have been identified within the Y. pestis genomes sequenced to date (1). Here, we report the comparative analysis of the virulent Y. pestis strain Angola, a representative of one of the most ancient Y. pestis lineages thus far sequenced. We studied adaptive microevolutionary traits Y. pestis has acquired and predicted the global Yersinia pangenome. By comparing the genomes of the three human pathogenic Yersinia species (12, 22), we investigated the global- and species-specific gene reservoir, the genome dynamics, and the degree of genetic diversity that is found within these species. Our genotypic and phenotypic analyses, as well as the refined single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogeny of Y. pestis, indicate that Angola is a deep-rooted isolate with unique genome characteristics intermediate between modern Y. pestis isolates and Y. pseudotuberculosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological material.

Y. pestis strain Angola was grown from a lyophilized stock prepared in 1984 at the U.S. Army Medical Institute for Infectious Diseases. Since then, the primary glycerol stock was passed in the laboratory only once for the purpose of this sequencing project. Strains CO92 and Pestoides A and F were used in the mutator assay. Female Swiss Webster mice, BALB/c mice, and Hartley guinea pigs were used to assess the virulence of strain Angola.

Genome sequencing, annotation, and analysis.

Genomic DNA of Y. pestis strain Angola was subjected to random shotgun sequencing and closure strategies as previously described (22). Random insert libraries of 3 to 5 kb and 10 to 12 kb were constructed, and 61,634 high-quality sequences of an 837-nt average read length were obtained. Draft genome sequences were assembled using the Celera assembler (38). The chromosome and the three plasmids were manually annotated using MANATEE (http://manatee.sourceforge.net/). To obtain copy numbers for the plasmids, their sequence coverage was calculated and normalized to the chromosome sequence coverage.

Comparative genomics and genome visualization.

The whole-genome alignment tool MUMmer (42) was used to calculate the overall gene identities of strain Angola to the Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica genomes. Each of the predicted genes of strain Angola was classified as conserved, shared, and unique according to the computed BLAST score ratio values and nucleotide identities. For each of the predicted proteins of Y. pestis Angola, a BLASTP raw score was obtained for the alignment against itself (REF_SCORE) and the most similar protein (QUE_SCORE) in each of the genomes of Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica. Dividing the QUE_SCORE obtained for each query genome protein by the REF_SCORE normalized these scores and constitutes the blast score ratio (BSR). Proteins with a normalized BSR of <0.4 were considered nonhomologous. A normalized BSR of 0.4 corresponded to two proteins being 30% identical over their entire length (56). Proteins with a normalized BSR of <0.4 were considered nonhomologous. A normalized BSR of 0.4 corresponded to two proteins being 30% identical over their entire length (56). The chi-squared values and G+C skews were computed from the Angola molecules as previously described (22, 51). For the chromosomal chi-square test, a window size of 2 kb and a sliding window of 1 kb were used, while a window size of 1 kb and a sliding window of 0.2 kb were used for the two plasmids. G+C skews were calculated using the software gcskew with a window size of 1 kb for the chromosome and 0.2 kb for the plasmids.

Rodent virulence studies. (i) LD50 determination in Swiss Webster mice.

To prepare inocula for aerosol and subcutaneous challenges, samples from frozen stocks were streaked on tryptose blood agar base slants and incubated at 28°C for 48 h. For the aerosol challenge, slants were flushed with heart infusion broth containing 0.2% xylose. The sample was adjusted to an A620 of 1.0, and 1 ml of this suspension was added to 100 ml of HIB-xylose (6). The liquid culture was incubated in a rotating shaker (150 rpm) in tightly capped flasks for 24 h at 30°C. Bacterial cells were pelleted and resuspended in heart infusion broth (HIB) (no added xylose). For aerosol exposure, starting concentrations were prepared as 10-fold serial dilutions from the highest dose. Mice (5 to 7 weeks old) were exposed using an ∼1-μm-generating Collison nebulizer contained within a class III biocabinet in a temperature- and humidity-controlled whole-body exposure chamber. The aerosol was continuously sampled by an all-glass impinger (AGI) containing HIB. The inhaled dose was determined from the serial dilution and culture of AGI samples according to the formula determined by Guyton (32). Samples of the starting material for aerosol exposures were diluted and spread on sheep blood agar plates (SBAP) to obtain the starting concentration. Samples collected in the AGIs were diluted and spread on SBAP. For the subcutaneous challenge, slants were flushed with 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and diluted to the desired concentration. Samples of the starting material were diluted and spread on SBAP plates to obtain the number of organisms administered to the animals. Animals were observed twice daily for at least 21 days postexposure, and 50% lethal dose (LD50) values were determined by probit analysis. For both aerosol and subcutaneous challenges, the LD50 studies included five groups of 10 animals each. The starting concentrations for the subcutaneous challenges were prepared as 10-fold serial dilutions from the highest dose. Mice were challenged subcutaneously between the scapulae with 200 ml of Y. pestis suspended in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7). Animals were observed twice daily for at least 21 days postexposure. LD50 values were determined by probit analysis.

(ii) Virulence in BALB/c mice and Hartley guinea pigs models.

The comparison of virulence in mice (20 g, 6 weeks old) and guinea pigs (0.8 to 1 kg) was done via the intradermal route of infection using strain Angola versus a control strain of typical Y. pestis CO92. The strains were introduced in suspensions using tuberculin syringes with 25- to 27-gauge needles with injection into the dermal layer of the skin (skin bubble). Each strain was delivered at the two doses of 1 × 102 and 1 × 106 CFU of each strain. Bacterial cells for injection were made by diluting suspensions from fresh slants. Animals were tested in groups of six. The animals were observed daily at 4-h intervals for 2 weeks. Relative virulence was determined by lethality and mean time to death for each dose.

Comparative mutational analysis.

Ten colonies of each Y. pestis strain analyzed were tested for spontaneous nalidixic acid resistance. Ten isolated colonies of each Y. pestis strain tested were grown in tubes containing 10 ml brain heart infusion (BHI) broth for 48 h at 28°C with shaking at 200 rpm. The A600 then was determined for each culture. For each bacterial suspension, a volume of 0.2 ml was streaked onto two BHI agar plates (50) containing nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml). The number of colonies on each plate was counted after incubation for 48 h at 28°C. The proportion of spontaneous resistance in the bacterial population was calculated for each tested strain as follows: mutation rate = (number of resistant colonies)(5)/(1.75 × 109)(A600 reading). The number of bacterial cells in one A600 unit is approximately 1.75 × 109 CFU/ml. The average of 10 mutation rate determinations then was calculated to arrive at the overall mutation rate for each strain.

Single-nucleotide polymorphism discovery.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms were identified in pairwise genome comparisons by comparing the predicted genes on the closed chromosome of Y. pestis strain CO92 to the completed genomes of strains KIM, Antiqua, Nepal516, 9001, and Pestoides F using MUMmer (19), and draft contigs were used for strains CA88-4125 (8) and FV-1 (63). By mapping the position of the SNP to the annotation in the reference strain CO92 genome, it was possible to determine the effect on the deduced polypeptide and classify each SNP as synonymous or nonsynonymous. For genomes with deposited underlying sequencing information, a polymorphic site was considered of high quality when it was represented by three underlying sequence reads with an average Phred quality score of greater than 30 (23). The SNP data set was manually curated, and positions within repeats and lateral acquired genomic regions were excluded from the phylogenetic analysis.

Phylogenetic analyses.

SNP data were analyzed further using the HKY93 algorithm (35) with 500 bootstrap replicates, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the PhyML algorithms (30). The Geneious software package (http://www.geneious.com) and SplitsTree4 (37) were used for visualization.

Core genes and gene discovery computation.

To compute the core gene, new gene, and pangenome estimates, all-versus-all WU-BLASTP and all-versus-all WU-TBLASTN were performed according to W. Gish (http://blast.wustl.edu) (5). The results from these two searches were combined such that the TBLASTN prevented missing gene annotations from producing false negatives. Hits were filtered such that homologues were defined as having 50% sequence similarity over at least 50% of the length of the protein.

Pangenome computation.

To compute core gene, new gene, and pangenome estimates, all-versus-all WU-BLASTP and -TBLASTN were performed (5). The determination of core genes and strain-specific genes depends on the number of genomes included in the analysis. The number (N) of independent measurements of the core and strain-specific genes present in the nth genome is N = S/ {(n − 1)!·(S − n)!}, where S is 14 (Y. pestis), 16 (Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis), and 17 (Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica). A random sampling of 1,000 measurements for each value of n was calculated to reduce the number of required computations. The numbers of core and strain-specific genes for a large number of sequenced isolates were extrapolated by fitting the exponential decaying functions Fc(n) = κc exp[−n/τc] + tgc(θ) and Fn(n) = κn exp[−n/τn] + tgn(θ), respectively, to the mean number of conserved and strain-specific genes calculated for all strain combinations. n is the number of sequenced strains, and κc, τc, κn, τn, tgc(θ), and tgn(θ) are free parameters. tgc(θ) and tgn(θ) represent the extrapolated number of core and strain-specific genes, assuming a consistent sampling mechanism and a large number of completed sequences. The pangenome itself represents an estimation of the complete gene pool based on the set of genomes analyzed and was computed in triplicates. In this case, a sample of at most 1,000 combinations for each value of n was taken and the total number of genes, both shared and strain specific, was calculated. To estimate the total number of genes accessible to the subsets of tested genomes or the pangenome, the median values at each n then were fitted with an exponential decay function as the core and new gene graphs.

Synteny analysis.

To study the genome dynamics, paralog clusters in each genome were computed by using the Jaccard algorithm according to reference 39 by applying a Jaccard coefficient of 0.6 and an 80% identity threshold. Members of paralog clusters then were organized into ortholog clusters by allowing any member of a paralog cluster to contribute to the reciprocal best matches used to construct the ortholog clusters. The presence or absence of a gene from the reference strain Angola in a query genome was determined based on whether the query genome had a member in the reference gene's ortholog cluster. Query gene matches are drawn above their reference gene hits and are colored based on the position in the query genome. Genes colored black indicate that there are multiple clusters in the reference genome. The gradient display was drawn using these ortholog clusters with the SYBIL software package (http://sybil.sourceforge.net/).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The Y. pestis Angola genome sequence (Project 16067) has been deposited under GenBank accession nos. CP000901 (chromosome), CP000900 (pMT-PCP), and CP000902 (pCD). The respective genome assemblies have been deposited in the NCBI Assembly Archive under ID3452 with an average coverage of 11.54×, and the 67,293 sequencing traces are available from the NCBI Trace Archive.

RESULTS

Genome architecture.

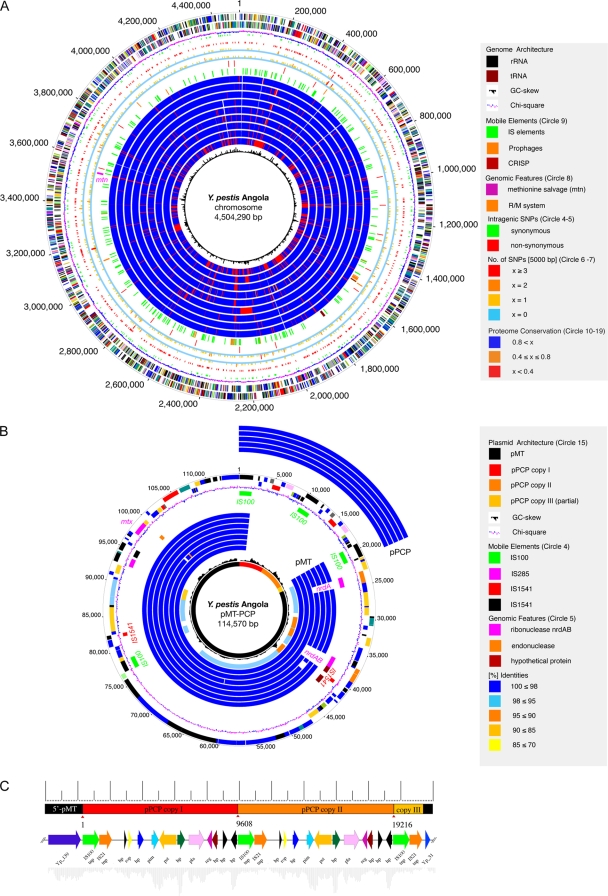

The chromosome of Y. pestis Angola consists of a circular molecule of 4,504,290 bp, with an average G+C content of 47.5% (Table 1, Fig. 1A). No well-defined G+C bias was observed, which is indicative of recent and frequent intrachromosomal recombinatorial events. The Angola mobile genome pool comprises the 69,190-bp pCD plasmid and a larger 114,570-bp chimeric plasmid, designated pMT-PCP, not previously seen in Y. pestis, which is composed of the murine toxin plasmid and two tandemly inserted copies of the plasminogen activator plasmid (Fig. 1B). The plasmid profile of strain Angola reveals the presence of an autonomous pPCP plasmid that replicates independently of the chimeric version and clearly shows the increased size of pMT-PCP compared to that of a typical pMT plasmid of strain CO92 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Gene dosage effects might be involved in pMT-PCP-borne pathogenicity, as the copy number of the chimeric plasmid is increased compared to that of isolates with a standard plasmid inventory. We estimated the strain Angola plasmid copy numbers by comparing the average plasmid sequence coverage to that of the chromosome with two pCD and four pMT-pPCP copies per chromosome for strain Angola, and the pMT-PCP plasmid clearly features the higher pPCP copy number under identical cultivation conditions. Thus, this chimeric plasmid appears to be under the replication control of pPCP, and its unique architecture might result in potential dosage effects of not only pPCP-borne but also pMT-borne virulence determinants.

TABLE 1.

Genomic features of Y. pestis Angola

| Genomic element | Molecule |

Open reading frame |

No. of noncoding RNAs |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | GC content (%) | Predicted no. | Coding area (%) | Avg length (bp) | rRNA | tRNA | |

| Chromosome | 4,504,290 | 47.5 | 4,255 | 82.7 | 879 | 20 | 70 |

| pCD | 68,190 | 44.7 | 105 | 79.2 | 514 | 0 | 0 |

| pMT-PCP | 114,570 | 50 | 145 | 84.6 | 668 | 0 | 0 |

| pPCP | 9,608 | 45.2 | 19 | 78.2 | 395 | 0 | 0 |

FIG. 1.

(A) Circular representation of the Y. pestis Angola chromosome. Circles, from outer to inner: predicted open reading frames encoded on the plus (1) and minus strands (2), colored according to the respective MANATEE roles; (3) G+C skew; (4) sSNP; (5) nsSNP; (6 and 7) genome-wide distribution of SNPs; (8) chromosomal regions of interest; (9) mobile elements; (10 to 18) comparative analysis of the Angola proteome to strains CO92 (10), KIM (11), Antiqua (12), Nepal516 (13), 91001 (14), and Pestoides F (15); interspecies comparison to Y. pseudotuberculosis strains IP32953 (16) and IP31758 (17) and Y. enterocolitica 8081 (18); (19) chi-square values. (B) Chimeric plasmid pMT-PCP. Circles, from outer to inner: (1 and 2) predicted open reading frames; (3) G+C skew; (4) mobile elements. Circle fragments for comparison to the pPCP plasmid are on the outside and show Y. pestis strains CO92 (1), KIM (2), 91001 (3), Antiqua (4), and Nepal516 (5); circle fragments for comparison to the pMT plasmids are on the inside and show strains CO92 (6), KIM (7), 91001 (8), Antiqua (9), Nepal516 (10), Pestoides F (11), and G8787 (12); circles for interspecies comparison to S. enterica CT18 pHCM2 plasmid (13); (14) chi-square values; (15) chimeric plasmid composition. Plasmid regions secondarily lost in the Y. pestis evolution, such as ribonucleases nrdAB and the Nepal516-specific 1,220-bp deletion of four hypothetical proteins with no assigned function (brown). (C) Architecture of pMT-PCP. The plasmid features a pPCP dimer integrated into the pMT plasmid in a head-to-tail arrangement.

Genome dynamics and gene inventory.

To study the Angola genome architecture, we investigated the population-wide genome dynamics among the seven closed Y. pestis genomes. The comprehensive intra- and interspecies analysis of the virulence plasmid and the chromosome architecture (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) reveals a high degree of intrachromosomal rearrangements in strain Angola, a characteristic feature of the Y. pestis genome evolution (17). The amino acid similarities show only marginal deviations within the analyzed Y. pestis isolates, and no obvious correlations between the traditional biovar classification and the degree of proteome conservation were detected (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), confirming the disconnect observed by Achtman et al. (1) between the biovar nomenclature and Y. pestis evolution. The species borders are clearly reflected in the interspecies comparisons of the Angola proteome to its closest phylogenetic neighbor, Y. pseudotuberculosis (12, 22), and to the more distantly related pathogen Y. enterocolitica (61). The chromosomes display only local microsynteny but no genome-wide synteny, and both the murine toxin plasmid pMT (see Fig. S2A in the supplemental material) and low-calcium-response plasmid pCD (pYV) (see Fig. S2B) feature multiple intraplasmid rearrangements. In contrast to these molecules, the organization of the Y. pestis-specific plasmid pPCP is highly syntenic. These observed rearrangements are associated with a massive expansion of insertion sequence (IS) elements and clearly distinguish strain Angola from its phylogenetic progenitor, Y. pseudotuberculosis (12, 22) (Fig. 1A). A similar role of IS element expansion in chromosomal reorganization has been implicated in the genome evolution and pathogenicity of Bordetella species (16). Besides the abundance of IS elements in strain Angola, we also observed isolate-specific propagation patterns of the four IS element types within Y. pestis that drive not only the reorganization of their genomic architecture (62) but also the microevolution of the metabolic capabilities (59) (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Ancestral metabolic capabilities and biovar designation.

Strain Angola is capable of fermenting glycerol and reducing nitrate and would be biochemically classified as a biovar ANT isolate (72). The nitrate reductase gene, napA (YpAngola_A2791), is identical to that of other Y. pestis nitrate reducers, while a new polymorphic state, an alanine-to-serine alteration at position 175 that is unique to Angola (GCA->TCA), was found in glpD (YpAngola_A4123), a glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase that is key to the identification of the glycerol fermentation phenotype.

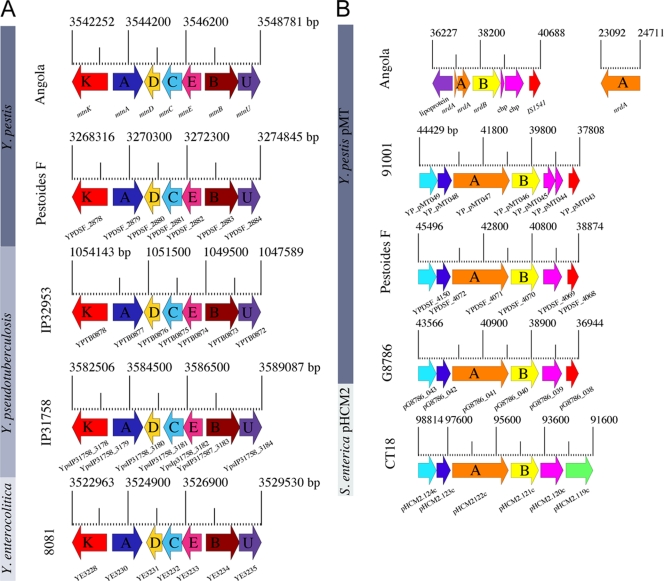

Angola is further associated with the Pestoides group originating in central Asia (7, 27, 59), because it can metabolize melibiose (mel) and rhamnose (rha). These ancestral capabilities can be used to differentiate Y. pestis from Y. pseudotuberculosis, as well as differentiate modern Y. pestis isolates from those of the deep-branching Pestoides group (48). In strain Angola, the rhamnose pathway (YpAngola_0737 to YpAngola_0748) consists of the transport gene rhaT, two regulatory transcriptional activators, rhaRS, three structural genes, rhaBAD, the lactalaldehyde reductase fucO and epimerase rhaU, and three interspersed hypothetical genes (YpAngola_0739, YpAngola_0741, and YpAngola_0742) with no assigned function (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Among the identified polymorphisms within the rha locus, only a single genetic polymorphism (CAC→CGC; position 671) in the transcriptional activator rhamnose RhaS was consistently observed in modern Y. pestis isolates (41). This regulator previously has been associated with the activation of rhamnose metabolism in Escherichia coli (67), and thus the observed arginine-to-histidine alteration most likely is responsible for the rhamnose-negative phenotype in modern isolates. Interestingly, unlike previous findings by Kukleva et al. (41), we detected sequence variations not only in the regulator rhaS but also in both structural subunits rhaB and rhaD, while all other genes were found to be genetically identical within Y. pestis (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). These differences are not consistent among rhamnose-positive or -negative isolates and thus certainly are not responsible for the conversion of the rhamnose phenotype in Y. pestis. However, within rhamnose-positive isolates, these genetic variations might account for observed differences in the kinetics of rhamnose metabolism (15). Further, strains Angola and Pestoides F (27) carry the methionine salvage pathway mtnKADCEBU (YpAngola_A3328 to YpAngola_A3333) (Fig. 2A). This salvage cycle maintains methionine levels by recycling methylthioadenosine (MTA), a product of the biosynthesis of polyamines into methionine (57). This pathway is conserved in Y. pseudotuberculosis serovar I strains IP31758 (22), IP32953 (12), PB1 (NC_010634), and serovar III strain YPIII (NC_010465), as well as the more distantly related Y. enterocolitica strain 8081 (61). The presence of these ancestral pathways in strain Angola and the progenitor Y. pseudotuberculosis suggests that these loci have been lost secondarily in modern Y. pestis but were present in the ancestral root of this lineage, thereby supporting the relationship of ancestral strain Angola to modern Y. pestis (Fig. 1A and 2A). This hypothesis is strengthened by the presence of a 5′-methylthioadenosine/S-adenosylhomocysteine nucleosidase (mtnN), a further component of the mtn pathway located elsewhere in the genome that is found in all sequenced Y. pestis strains (22).

FIG. 2.

Ancestral genome features of Y. pestis Angola. (A) Prevalence of the methionine salvage locus. Strain Angola and the deep-branching Pestoides group isolate F are the only known Y. pestis isolates that carry the methionine salvage pathway on their chromosomes. Its presence in the phylogenetic ancestors Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica argues for a secondary loss of this metabolic property in descending Y. pestis isolates. The scale, in base pairs, indicates the genomic location of the methionine salvage locus composed of the seven genes mtnKADCEBU. Genes shared between these highly conserved and syntenically arranged loci are colored accordingly. (B) Prevalence of the nrdAB locus. Strain Angola encodes another locus on its chimeric plasmid, the ribonucleotide diphosphate reductase nrdAB operon, which most likely was lost secondarily in descending Y. pestis isolates. Corresponding loci are found only in other deep-branching Y. pestis strains: the Pestoides group isolates F and G8786 and the 0.PE4 microtus strain 91001. Besides Y. pestis, this locus also is present in the phylogenetically related pHCM2 plasmid of S. enterica CT18. In Y. pestis strain 91001, one of the two conserved hypothetical proteins appears to be degenerated (YP_pMT44, YP_pMT45). The scale, in base pairs, indicates the genomic location of the nrdAB operon. Genes shared between these loci are colored accordingly.

Microevolution of the virulence plasmids.

We investigated microevolutionary processes that might have shaped the organization of Angola virulence plasmids. The genomic analysis of strain Angola reveals a unique chimeric 114,570-bp plasmid featuring an architecture not observed in any Y. pestis isolates sequenced previously (Fig. 1B). Unusual sizes among the typical virulence plasmids previously were attributed to intrachromosomal deletions and the lateral acquisition of genomic fragments (28). It is noteworthy that architectural variations consisting of independently replicating pPCP dimers have been reported in strains isolated from the western United States (14). The pMT-PCP plasmid is composed of the murine toxin plasmid disrupted by two tandemly repeated copies of the pPCP plasmid. This architecture accounts for the large plasmid size and deviating G+C content in a head-to-tail arrangement (Fig. 1C). The presence of the IS100 element (Fig. 1B) on both virulence plasmids might have facilitated the mechanistic process of cointegration via double homologous recombination, resulting in the chimeric nature of this plasmid. It is not clear if the presence of this chimeric plasmid provides any advantage to strain Angola or arose due to defects in plasmid maintenance and the replication of pMT and pPCP. Enzymatic defects cause incomplete partitioning during replication and decatenation and might result in the dimeric plasmid (14). We speculate that the unique plasmid architecture in Angola helps to guarantee a stable maintenance of both plasmids pMT and pPCP, as these two virulence plasmids are known to be unstable in Y. pestis (44). Indeed, other Pestoides isolates lack one of the two species-specific virulence plasmids (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) (9, 27), and we found the chimeric plasmid to be stable even after extensive laboratory cultivation. The plasmid profile of four Pestoides isolates shows atypically large pMT plasmids (9). However, in at least two of these strains, Pestoides F (27) and G8786 (28), the larger size is the result of additional conjugal transfer system genes and evolved independently from the Angola-specific pPCP dimer integration. The Angola genome carries three copies of the plasmid-associated plasminogen activator genes (pla) that help promote the dissemination of Y. pestis through peripheral infection routes (43). Thus, gene dosage effects of Pla virulence determinants might affect the pathogenic potential of strain Angola via endogenous plasmid control (60). The lateral acquisition of these two virulence plasmids was a key step in the Y. pestis speciation and contributed to its evolutionary transformation from an enteric pathogen into a highly host-adapted mammalian blood-borne pathogen. The finding of this unique plasmid structure in this ancestral strain lets us speculate about a possible acquisition of both species-specific Y. pestis virulence plasmids in a single event during speciation from Y. pseudotuberculosis. The chimeric plasmid carries further ancestral signatures with homology to Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18 plasmid pHCM2 (52), such as the ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductases nrdAB (Fig. 1B, 2B). This particular region, which is absent from all modern Y. pestis isolates, most likely was lost secondarily in the evolution of Y. pestis, as no difference in the overall G+C skew of this region and the plasmid backbone was observed (Fig. 1B). The observed prevalence of this fragment again supports a deeply rooted position of Angola in the Y. pestis phylogeny and also a close relationship to central Asian Pestoides isolates. The murine toxin component of the chimeric plasmid pMT-PCP carries a 6-kb region that displays more than 95% nucleotide similarity to the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18 plasmid pHCM2 (52) (Fig. 1B). In Y. pestis it is present only in three other deep-branching isolates: the 0.PE4 microtus strain 91001 (59) and both substantially enlarged pMT plasmids of the Pestoides group, strains G8786 (137,036 bp) (28) and F (0.PE2a) (137,010 bp) (27). The prevalence strengthens the previously suggested phylogenetic relationship between the Y. pestis murine toxin plasmid and the S. enterica CT18 pHCM2 plasmid (55) and further supports the suggestion that they share ancestry as well as being able to exchange genetic material. The latter suggestion is supported by the high sequence similarity of the Y. pestis multidrug resistance (MDR)-conferring plasmid pIP1202 (26, 65) to IncA/C enteric MDR plasmids (52, 58, 65). This remnant 6-kb fragment encodes the alpha (nrdA) and beta (nrdA) subunits of the ribonucleoside-diphosphate reductase, which is involved in deoxyribonucleotide metabolism, and two hypothetical proteins with no assigned function (Fig. 2B). Comparative analyses of the plasmids Y. pestis pMT and S. enterica pHCM2 show that both the alpha subunit of the ribonucleoside phosphatase (33) and the conserved hypothetical proteins might be in the process of decay in strain Angola. Strain Angola carries two truncated nrdA pseudogenes (Fig. 2B, orange), while these genes appear to be intact and potentially functional in Pestoides group strains F and G8786 as well as in S. enterica CT18. Interestingly, in strain Angola, a second intact RNase copy is found 11.5 kb upstream from the first copy on the chimeric plasmid (Fig. 1B) and may functionally complement the degenerated nrdA pseudogenes.

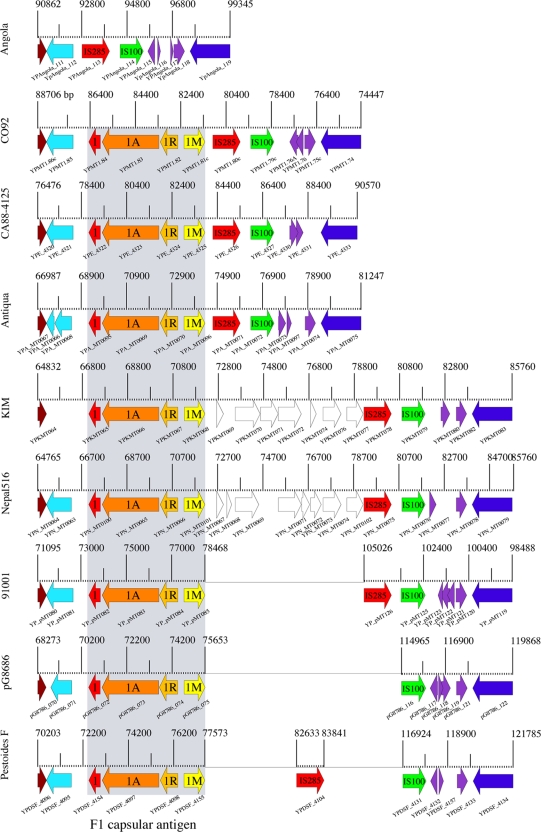

Deletion of the plasmid-borne capsular antigen.

Angola is the only Y. pestis isolate sequenced to date that lacks the complete pMT-borne capsular antigen (caf) on its chimeric plasmid (Fig. 1B). This species-specific operon forms the F1 capsular antigen and is syntenically organized in all previously studied isolates (13, 20, 28, 53, 59) (Fig. 3). The F1 locus is comprised of four genes that encode the structural subunit Caf1, the molecular chaperone Caf1M, the outer membrane anchor Caf1A, and the regulator Caf1R (40). The 5′-flanking region of the operon is highly conserved, but we found structural rearrangements in the adjacent 3′ region. It is not clear if the absence of the capsule in Angola is due to a secondary loss or represents an ancestral state. Indeed, the capsular antigen is not essential for the manifestation of Y. pestis virulence but rather contributes to pathogenicity (18). The ancestral position of Angola let us speculate in favor of a lateral acquisition of this virulence determinant during Y. pestis microevolution. This hypothesis is supported by a deviating G+C content within the antigen region observed for all analyzed F1-positive murine toxin plasmids. It is noteworthy that another pMT-borne virulence determinant, the murine toxin (mtx) (YpAngola_0119), also shows a G+C abnormality (Fig. 1B). Thus, it appears that both species-specific virulence determinants most likely were secondarily incorporated into the plasmid backbone, and their presence in Y. pestis does not represent the ancestral state of the pMT coding capacity (Fig. 1B). The genetic rearrangements at this locus might have been mechanistically facilitated by mobile genetic elements that are located downstream of the F1 locus. Although other nonencapsulated Y. pestis strains (54) as well as strains that express reduced amounts of the capsular antigen (68) have been reported from natural sources, their genomic architecture at this locus remains unknown. Such F1-negative strains are able to evade standard diagnostic assays specific for this surface-exposed antigen, and they potentially delay the essential immediate antibiotic treatment required to be administered according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention within the first 24 h postinfection. A possible emergence of this novel described Angola genotype raises questions about public health as well as future plague surveillance and treatment.

FIG. 3.

Genomic architecture of the F1 capsular antigen. The F1 capsule is present and syntenically organized in all previously sequenced Y. pestis genomes, while strain Angola is the only currently known Y. pestis isolate that lacks the complete operon. Genes shared between these loci are colored accordingly.

Assessment of virulence.

The specific genetic make-up that allows Y. pestis to cause bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic plague rather than enteric disease is not fully understood (73). The ancient nature of Angola makes it of particular importance in gaining insights into the evolution of Y. pestis virulence. Although the capsule could be an important virulence factor in certain rodent hosts in nature, strains lacking F1 retain virulence in laboratory animal models, including nonhuman primates (18, 70). The capsule is thought to be involved in Y. pestis pathogenesis, in particular by inhibiting phagocytosis, but is not a prerequisite for full virulence (25, 69). However, the capsule presumably is involved in the intimate bacterium-host interaction, and one can hypothesize that its absence in strain Angola, together with the other genetic polymorphisms identified in this isolate, affect the pathogenic potential. To test this hypothesis, we examined the virulence of Angola in three rodent plague models, the outbred mouse, inbred mouse, and guinea pig, testing different routes of infection.

The use of both mice and guinea pigs to assay virulence is based on the observation that nonepidemic, enzootic Pestoides subspecies show attenuated virulence phenotypes in guinea pigs, but typically they are fully virulent in the rodent superfamily Muroidea (7). Indeed, Angola did not cause lethality in the guinea pig after either 102- or 106-CFU subcutaneous doses, while the epidemic strain CO92 was 100% lethal at both doses (Table 2). A deficiency in the capsular antigen previously has been attributed to reduced virulence in guinea pigs (10). However, the lack of the capsular antigen in strain Angola does not necessarily indicate low virulence, but the first-ever reported complete absence of this surface-exposed capsule may affect the intimate bacterium-host interactions by altering the immune response of the mammalian host (15). A recent study of genetically engineered CAF-deficient mutants also suggests a role of the F1 antigen in promoting plague transmission by fleas (54). This finding also might hold true in the genetic background of strain Angola.

TABLE 2.

Virulence assay of Y. pestis Angolaa

| Assay and infection method | Inoculum (CFU) | TTD (days) | L/T |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss Webster mice LD50 | |||

| Aerosol challenge | 3.6 × 104 | 7.6 (8,000 CFU) | 25/50 |

| Subcutaneous challenge | 1,153 | 7.6 (8,000 CFU) | 25/50 |

| Pathogenic potential in mice and guinea pigs (intradermal challenge) | |||

| BALBc/inbred mice | 102 | 8 | 6/18 |

| 106 | 8.7 | 18/18 | |

| Hartley guinea pigs | 102 | NA | 0/18 |

| 106 | NA | 0/18 |

The virulence of Y. pestis Angola was assayed in two laboratory rodent models following subcutaneous, intradermal, and aerosol challenge. Relative virulence was determined by lethality and mean time to death for each dose. L/T, observed lethality/total number of animals infected; TTD, mean time to death postexposure; NA, not applicable.

In Swiss Webster mice, Angola was fully virulent by the aerosol route but was significantly less virulent than a typical Y. pestis strain in a subcutaneous challenge. The 50% median lethal dose (LD50) in aerosol-infected mice was 3.6 × 104 CFU, which is comparable to that of modern Y. pestis strains. However, the LD50 for Angola by the subcutaneous route was 1,153 CFU, which is relatively high compared to the LD50 of strain CO92 (2 CFU). Thus, there is a 500-fold difference in the LD50s of these two strains by the parenteral route. The mean time to death (TTD) also was increased in Angola (8,000 CFU; 7.6 days), while for CO92 the TTD at a lower dose of 4,000 CFU was significantly less (4.8 days) (Table 2) (66).

Our data suggest that the Angola virulence in the subcutaneous mouse model, but not by the aerosol route of infection, is affected by the reported strain-specific polymorphisms that are intimately associated with its pathogenic potential (7, 10, 34). It is noteworthy that the ability of Y. pestis to cause a fatal pneumonic disease in mice appears to have evolved early, as it is present in this ancient strain. However, it appears to lack some of the capability of typical Y. pestis strains to invade via parenteral routes.

The identification of such a naturally occurring, albeit rare, F1-negative strain, along with its ability to cause lethal pneumonic plague, has major public health implications. The F1 antigen is an important genomic marker traditionally used in diagnostics. Its complete absence demonstrates that this locus is not an ideal candidate for the development of future plague vaccines, and other targets need to be identified (18, 25). It has been suggested that Y. pestis isolates such as Angola, which are virulent in mice but not in guinea pigs, present a reduced virulence in humans (7, 59). However, there are a number of documented problems with guinea pig plague models, and the projection of such animal model-based results on human plague virulence remains a point of debate (4).

Phylogenetic position of strain Angola.

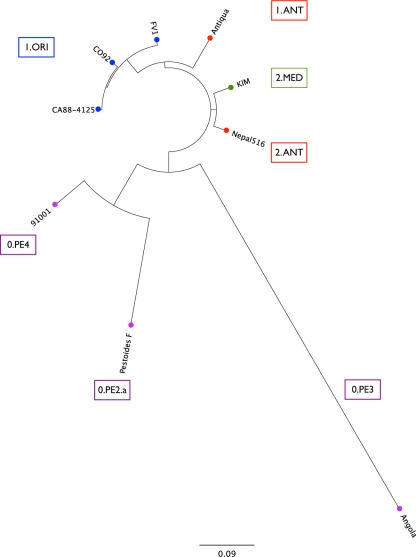

Detailed genome comparisons of this evolutionarily young pathogen enabled us to investigate important but rare genetic polymorphisms that determine the isolates' evolutionary relationships. The described genotypic signatures on the chromosome and plasmids of Y. pestis Angola clearly indicate a close relationship of strain Angola to the Pestoides group, which is suggestive for an ancestral phylogenetic positioning of Angola within the Y. pestis lineage (45) (Fig. 1, 2, and 4). The relationship of strain Angola to central Asian Y. pestis isolates is supported by our analysis of two previously deployed markers, such as the variable number of tandem repeats (VNTRs) and low-calcium-response V antigen (7, 45). We found that the pCD-borne lcrV gene of strain Angola (3) and the Y. pestis subsp. hissarica strain A-1728 (DQ489552) show an identical genetic make-up, carrying three nonsynonymous SNPs at positions 54, 215, and 817. This finding is consistent with their alleged ancestral status, as the African strain Angola and these analyzed Asian subspecies show a high degree of diversity in the lcrV antigen compared to those of descending modern Y. pestis isolates (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). However, due to the genetically homogenous nature of the Y. pestis population, the application of these genotyping methodologies is, in many cases, beyond the resolution threshold and cannot resolve the individual phylogenetic relationships of distinct Y. pestis isolates. To resolve the population structure, we applied an SNP-based genotyping methodology using the modern 1.ORI strain CO92 as the reference genome (8, 13, 20, 27, 53, 59, 63). In this study, we identified for the species a total of 424 synonymous SNPs (sSNPs) and 1,006 nonsynonymous SNPs (nsSNPs) (see Table S3 in the supplemental material), which is far more than previously reported (1). Genetic differences at the nucleotide level within the species previously have been attributed to less than 133 sSNPs and 349 nsSNPs (1, 2, 13). The Angola genome harbors the largest number of SNPs ever reported for a Y. pestis isolate compared to that of a modern 1.ORI isolate (i.e., Y. pestis CO92), carrying a total of 258 sSNPs and 502 nsSNPs. In addition, Angola features the largest number (210 sSNPs, 383 nsSNPs) of unique strain-specific sSNPs. Considering the large number of unique SNP identified in strain Angola, we investigated the possibility that this isolate is rapidly evolving through a mutator genotype. However, as evidenced in comparative nalidixic acid resistance assays (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material), no significant differences were found in Angola mutability compared to that of CO92. In support of the nonmutator genotype, comprehensive analyses of genes encoding the DNA mismatch repair system MutHLS (YpAngola_A3242, YpAngola_A0701, and YpAngola_A3242) and nucleotide excision repair UvrABCD systems (YpAngola_A0751, YpAngola_A1430, YpAngola_A2053, and YpAngola_A0545) did not indicate any genetic differences that could affect Angola's mutation rate, as these loci are present and nondegenerated in strain Angola.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic position of Y. pestis Angola. The phylogenetic tree is based on 424 sSNPs and 1,006 nsSNPs and reveals a deep branching of the 0.PE3 strain Angola within Y. pestis. Branch designations were assigned according to the nomenclature introduced by Achtman et al. (1). Strains biochemically classified into the same biovar are colored accordingly.

The SNP-based phylogeny (Fig. 4) reveals that Angola is one of the most ancestral and deep-rooted Y. pestis isolates analyzed to date, a finding consistent with the ancestral genome features we could identify in the Angola genome (Fig. 2 and 4; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Our phylogenetic analyses place strain Angola on the 0.PE3 branch and thus in a proximal position to the Pestoides group isolates F (0.PE2a) and 91001 (0.PE4) (1, 27). These two central Asian Pestoides group isolates are of different geographical origin than the African strain Angola, although the phylogenetic relationships of strains from central Asia and Africa have been observed previously by different classification methods, such as ribonucleoside or IS element genotyping (31, 49). The phylogeny further supports the hypothesis that biovars MED and ORI arose through parallel evolution from a biovar ANT progenitor due to the acquisition of independent mutations (29, 49). However, as demonstrated for strain Angola, grouping Y. pestis according to the classical definition of biovars on the basis of a few biochemical properties does not accurately reflect and resolve their phylogenetic relationship. This refined evolutionary history of Y. pestis clearly supports a grouping of Y. pestis into populations rather than biovars, as suggested by Achtman et al. (1).

The core genome and pangenome of the plague bacterium.

We predicted, for the first time, the set of nonorthologous genes within the species, the Y. pestis pangenome, including chromosome- and plasmid-borne sequences of a given strain (47). This data set contained the genomes of four evolutionarily key strains isolated from the zoonotic rodent reservoir in foci of endemic plague in China (21a). The core genome and gene discovery computations are visualized in Fig. 5. Unlike the major role of lateral transfer that drives genome evolution in the ancestor Y. pseudotuberculosis (22), the gene repertoire of Y. pestis is not significantly expanding by the acquisition of new genes (Fig. 5A). The core genome, i.e., genes present in all 14 genomes analyzed, consists of 3,668 protein-coding genes, of which more than 94% are present in Y. pestis CO92. The ancestral loci maintained in the Pestoides group isolates and Angola, such as the methionine salvage pathway, still are part of the global gene pool of Y. pestis, but they have undergone a reductive evolution in descending Y. pestis isolates (Fig. 2A; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). On average, only 21 new genes would be discovered for each additional Y. pestis genome sequenced (Fig. 5B). These analyses clearly reflect the genetically homogenous nature of the Y. pestis population structure (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), and the results are comparable to data obtained for other evolutionarily young pathogens, such as Bacillus anthracis (47). The gene discovery rate was found to be significantly increased by the inclusion of Y. pestis strain IP275 (26) (Fig. 5B). This strain introduces more than 200 genes into the species gene pool, all of which are carried on the isolate-specific MDR plasmid pIP1202; none are found on its chromosome. This emphasizes the potential impact of such isolate-specific plasmid inventory in the genome evolution of Y. pestis (Fig. 5A) (1, 46). In this context, it is noteworthy that the closest relatives, Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. enterocolitica, clearly have evolved by the acquisition of isolate-specific plasmids (22). The finding of the unique chimeric virulence plasmid, although it does not introduce novel genetic information into the species genome pool, provides further evidence for an open, yet-to-be-discovered Y. pestis panmobilome. Growing evidence suggests that the plasmid repertoire of Y. pestis is not restricted to the three classical virulence plasmids (24), and that its genetic inventory is partly shared, either due to common ancestry or lateral exchange, with other human and zoonotic bacterial pathogens, such as S. enterica, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (52, 65), Klebsiella pneumoniae (58), and Streptococcus equi (36). The potential dissemination of genetic information between Y. pestis and other pathogens might be advantageous for strain-specific niche adaptations and bacterial fitness but also potentially impacts the pathogenic potential and should be considered in the future program development for plague surveillance, prophylaxis, and treatment.

FIG. 5.

Core genes and gene discovery in human pathogenic Yersinia. (A) Core genes. For each number of genomes n, circles are the permutations for Y. pestis values obtained for a sampling size of 1,000. Diamonds and triangles give median and mean values for each distribution. The curve represents the exponential regression of the least-squares fit of Fcore(n) = κc exp[−n/τc] + tgc(θ). The extrapolated core genome size is shown as a horizontal dashed red line. (B) Gene discovery. The numbers of new genes found are plotted for increasing values of n. The curve is the least-squares fit of the exponential decay Fnew(n) = κn exp[−n/τn] + tgn(θ) based on the means of the distribution. The value of tgn(θ) shown represents the number of new genes asymptotically predicted for further genome sequencing. Core genes (C, E) and gene discovery (D, F) when Y. pseudotuberculosis strains IP31758 and IP32953 and Y. enterocolitica 8081 are included.

Crossing the species border, we included the two other human pathogenic Yersinia species: Y. pseudotuberculosis, represented by the far-eastern scarlatiniform and pseudotuberculosis-causing strains IP31758 and IP32953 (12, 22), and Y. enterocolitica 8081 (61). When Y. pseudotuberculosis is included, the number of conserved core genes within these two species decreases slightly to 3,450 genes, while the predicted number of new genes for each new genome sequenced increases to 54 (Fig. 5E and F). Given the high degree of proteome conservation between Y. pestis and its progenitor Y. pseudotuberculosis (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), the species border is not well defined and the computed core gene sets differ by only 218 genes. This finding is supported by the close phylogenetic relationship between these two Yersinia species (12, 22) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the evolutionary distance between Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis to the phylogenetically distant Y. enterocolitica strain 8081 is clearly visible in Fig. 5E and F. The conserved gene set shrinks by 30% to 2,400 genes present in all three human pathogenic Yersinia species sequenced to date. This decrease reflects the estimated 1.9 million years of evolution separating Y. pseudotuberculosis and its phylogenetic descendants Y. pestis and Y. enterocolitica (2).

The predicted pangenome defines the global gene reservoir, the total number of genes found at least once among the 14 genomes analyzed, of this group and is estimated to consist of 4,844 genes for Y. pestis (Fig. 6A), and it is only 19% larger than the proteome of Y. pestis strain CO92 (53). Our pangenome computation indicates that the Y. pestis core genome reaches a minimum of genes and remains relatively constant, even as more genomes are added, indicating that Y. pestis as a species has a closed pangenome. On the contrary, in a species featuring an open pangenome, such as Escherichia coli, the predicted pangenome size was found to be almost 75% larger than the average genome size of the species (64). The global Yersinia pangenomes are predicted to consist of a gene pool of 6,004 genes for Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis (Fig. 6B) and 7,311 genes when Y. enterocolitica is included in the analysis (Fig. 6C). The 25 and 50% increases in pangenome sizes compared to that of the Y. pestis-only pangenome mirrors the phylogenetic relationships and individual traits of genome evolution within this group of organisms. The differences in the global gene pool across the species borders is caused by the observed reductive evolution in Y. pestis (22) (Fig. 2 and 4; also see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and by the influx of genetic material, such as the horizontal acquisition of species- and isolate-specific plasmids, together with the incorporation of different genetic information into the chromosome of these two enteric Yersinia species (22, 61).

FIG. 6.

Pangenome of human pathogenic Yersinia. (A) Pangenome of Y. pestis. The total number of genes found according to the pangenome analyses is shown for increasing values of the number n of Yersinia genomes sequenced using medians and an exponential fit. Red diamonds indicate the means of the distributions. The dashed line represents the total number of genes that comprise the respective pangenome asymptotically predicted for further genome sequencing. (B) The two-species pangenome computed for Y. pestis and the closest evolutionary ancestor Y. pseudotuberculosis. (C) The three-species Yersinia pangenome computed for Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica.

DISCUSSION

Evolutionary considerations.

The sequencing and phylogenomic analyses of this evolutionary Y. pestis key isolate advances our understanding of the speciation of this highly host-adapted pathogen from its enteric progenitor, Y. pseudotuberculosis. This study identified distinct adaptive microevolutionary traits that shaped the genome organization and gene inventory of this atypical African isolate and let us conclude that Angola belongs to one of the most ancient Y. pestis lineages thus far sequenced. Atypical Y. pestis strains have been reported to exist in natural foci in central Asia and are classified as the Pestoides group of isolates to acknowledge their distinct genetic, biochemical, and virulence properties (7, 70). However, strain Angola is the first African Y. pestis isolate that can be identified as a representative of these ancestral lineages. Making use of the newly identified Angola genotypic and phenotypic characteristics will help to achieve a higher phylogenetic resolution in this genetically homogenous pathogen. The microevolution seems to be driven by isolate-specific genetic polymorphisms and by a high rate of intrachromosomal rearrangements driven by IS elements. Because the Angola genome has experienced such expansion, it is suggested that this phenomenon occurred soon after the split of Y. pestis from Y. pseudotuberculosis. Its mobilome further demonstrates that the Y. pestis plasmid repertoire is not restricted to the classical virulence plasmids. The unique chimeric virulence plasmid clearly shows the major impact of an isolate-specific plasmid inventory in the genome evolution in this otherwise genetically homogenous pathogen and provides further evidence for an open panmobilome.

Genomic plasticity in Y. pestis.

The unique genetic traits in the Angola genome identified in this study, together with the largest number of isolate-specific SNPs, clearly support the existence of a yet-undiscovered genetic diversity within Y. pestis that is not as limited as previously thought. Thus, to gain further insights into the existing and evolving genetic diversity of Y. pestis, it is essential to continue gathering additional sequence data. The possible emergence of fully virulent F1-negative isolates capable of evading standard diagnostic assays raises major public health concerns and should be considered in future plague surveillance. Owing to the critical importance of Y. pestis for human health, the key to understanding the emergence and impact of such previously unknown genotypes, some of which are associated with plague pathogenicity and epidemiology, resides in the sampling and characterization of more isolates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under NIAID contract N01 AI-30071, and Defense Threat Reduction Agency JSTO-CBD project 1.1A0021_07_RD_B (P.W.L.).

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

We thank Richard Borschel for performing the guinea pig assay.

Research was conducted in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations involving animals and adheres to the principles stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 1996. The facility where this animal research was conducted is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 January 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman, M., G. Morelli, P. Zhu, T. Wirth, I. Diehl, B. Kusecek, A. J. Vogler, D. M. Wagner, C. J. Allender, W. R. Easterday, V. Chenal-Francisque, P. Worsham, N. R. Thomson, J. Parkhill, L. E. Lindler, E. Carniel, and P. Keim. 2004. Microevolution and history of the plague bacillus, Yersinia pestis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:17837-17842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Achtman, M., K. Zurth, G. Morelli, G. Torrea, A. Guiyoule, and E. Carniel. 1999. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:14043-14048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adair, D. M., P. L. Worsham, K. K. Hill, A. M. Klevytska, P. J. Jackson, A. M. Friedlander, and P. Keim. 2000. Diversity in a variable-number tandem repeat from Yersinia pestis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1516-1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adamovicz, J. L., and P. L. Worsham. 2006. Plague, p. 107-135. In J. R. Swearengen (ed.), Biodefense: research methodology and animal models. CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL.

- 5.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson, G. W., Jr., S. E. Leary, E. D. Williamson, R. W. Titball, S. L. Welkos, P. L. Worsham, and A. M. Friedlander. 1996. Recombinant V antigen protects mice against pneumonic and bubonic plague caused by F1-capsule-positive and -negative strains of Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 64:4580-4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anisimov, A. P., L. E. Lindler, and G. B. Pier. 2004. Intraspecific diversity of Yersinia pestis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17:434-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auerbach, R. K., A. Tuanyok, W. S. Probert, L. Kenefic, A. J. Vogler, D. C. Bruce, C. Munk, T. S. Brettin, M. Eppinger, J. Ravel, D. M. Wagner, and P. Keim. 2007. Yersinia pestis evolution on a small timescale: comparison of whole genome sequences from North America. PLoS One 2:e770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bearden, S. W., C. Sexton, J. Pare, J. M. Fowler, C. G. Arvidson, L. Yerman, R. E. Viola, and R. R. Brubaker. 2009. Attenuated enzootic (pestoides) isolates of Yersinia pestis express active aspartase. Microbiology 155:198-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burrows, T. W. 1957. Virulence of Pasteurella pestis. Nature 179:1246-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carniel, E., and B. J. Hinnebusch (ed.). 2004. Yersinia molecular and cellular biology. Horizon Biosciences, Norfolk NR18 0JA, United Kingdom.

- 12.Chain, P. S., E. Carniel, F. W. Larimer, J. Lamerdin, P. O. Stoutland, W. M. Regala, A. M. Georgescu, L. M. Vergez, M. L. Land, V. L. Motin, R. R. Brubaker, J. Fowler, J. Hinnebusch, M. Marceau, C. Medigue, M. Simonet, V. Chenal-Francisque, B. Souza, D. Dacheux, J. M. Elliott, A. Derbise, L. J. Hauser, and E. Garcia. 2004. Insights into the evolution of Yersinia pestis through whole-genome comparison with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:13826-13831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chain, P. S. G., P. Hu, S. A. Malfatti, L. Radnedge, F. Larimer, L. M. Vergez, P. Worsham, M. C. Chu, and G. L. Andersen. 2006. Complete genome sequence of Yersinia pestis strains Antiqua and Nepal516: evidence of gene reduction in an emerging pathogen. J. Bacteriol. 188:4453-4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu, M. C., X. Q. Dong, X. Zhou, and C. F. Garon. 1998. A cryptic 19-kilobase plasmid associated with U.S. isolates of Yersinia pestis: a dimer of the 9.5-kilobase plasmid. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 59:679-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cornelius, C. A., L. E. Quenee, D. Elli, N. A. Ciletti, and O. Schneewind. 2009. Yersinia pestis IS1541 transposition provides for escape from plague immunity. Infect. Immun. 77:1807-1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cummings, C. A., M. M. Brinig, P. W. Lepp, S. van de Pas, and D. A. Relman. 2004. Bordetella species are distinguished by patterns of substantial gene loss and host adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 186:1484-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darling, A. E., I. Miklos, and M. A. Ragan. 2008. Dynamics of genome rearrangement in bacterial populations. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis, K. J., D. L. Fritz, M. L. Pitt, S. L. Welkos, P. L. Worsham, and A. M. Friedlander. 1996. Pathology of experimental pneumonic plague produced by fraction 1-positive and fraction 1-negative Yersinia pestis in African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops). Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 120:156-163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delcher, A. L., A. Phillippy, J. Carlton, and S. L. Salzberg. 2002. Fast algorithms for large-scale genome alignment and comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2478-2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deng, W., V. Burland, G. Plunkett, 3rd, A. Boutin, G. F. Mayhew, P. Liss, N. T. Perna, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, J. D. Fetherston, L. E. Lindler, R. R. Brubaker, G. V. Plano, S. C. Straley, K. A. McDonough, M. L. Nilles, J. S. Matson, F. R. Blattner, and R. D. Perry. 2002. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis KIM. J. Bacteriol. 184:4601-4611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devignat, R. 1953. Geographical distribution of three species of Pasteurella pestis. Schweiz. Z Pathol. Bakteriol. 16:509-514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Eppinger, M., Z. Guo, Y. Sebastian, Y. Song, L. E. Lindler, R. Yang, and J. Ravel. 2009. Draft genome sequences of Yersinia pestis isolates from natural foci of endemic plague in China. J. Bacteriol. 191:7628-7629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eppinger, M., M. J. Rosovitz, W. F. Fricke, D. A. Rasko, G. Kokorina, C. Fayolle, L. E. Lindler, E. Carniel, and J. Ravel. 2007. The complete genome sequence of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP31758, the causative agent of Far East scarlet-like fever. PLoS Genet. 3:e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ewing, B., L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, and P. Green. 1998. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 8:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filippov, A. A., N. S. Solodovnikov, L. M. Kookleva, and O. A. Protsenko. 1990. Plasmid content in Yersinia pestis strains of different origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 55:45-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedlander, A. M., S. L. Welkos, P. L. Worsham, G. P. Andrews, D. G. Heath, G. W. Anderson, Jr., M. L. Pitt, J. Estep, and K. Davis. 1995. Relationship between virulence and immunity as revealed in recent studies of the F1 capsule of Yersinia pestis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21(Suppl. 2):S178-S181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Galimand, M., A. Guiyoule, G. Gerbaud, B. Rasoamanana, S. Chanteau, E. Carniel, and P. Courvalin. 1997. Multidrug resistance in Yersinia pestis mediated by a transferable plasmid. N. Engl. J. Med. 337:677-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia, E., P. Worsham, S. Bearden, S. Malfatti, D. Lang, F. Larimer, L. Lindler, and P. Chain. 2007. Pestoides F, an atypical Yersinia pestis strain from the former Soviet Union. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 603:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golubov, A., H. Neubauer, C. Nolting, J. Heesemann, and A. Rakin. 2004. Structural organization of the pFra virulence-associated plasmid of rhamnose-positive Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 72:5613-5621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez, M. D., C. A. Lichtensteiger, R. Caughlan, and E. R. Vimr. 2002. Conserved filamentous prophage in Escherichia coli O18:K1:H7 and Yersinia pestis biovar orientalis. J. Bacteriol. 184:6050-6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guindon, S., F. Lethiec, P. Duroux, and O. Gascuel. 2005. PHYML Online—a web server for fast maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic inference. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W557-W559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guiyoule, A., F. Grimont, I. Iteman, P. A. Grimont, M. Lefevre, and E. Carniel. 1994. Plague pandemics investigated by ribotyping of Yersinia pestis strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guyton, A. C. 1947. Measurement of the respiratory volumes of laboratory animals. Am. J. Physiol. 150:70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacker, J., B. Hochhut, B. Middendorf, G. Schneider, C. Buchrieser, G. Gottschalk, and U. Dobrindt. 2004. Pathogenomics of mobile genetic elements of toxigenic bacteria. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 293:453-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haiko, J., M. Kukkonen, J. J. Ravantti, B. Westerlund-Wikstrom, and T. K. Korhonen. 2009. The single substitution I259T conserved in the plasminogen activator Pla of pandemic Yersinia pestis branches enhances fibrinolytic activity. J. Bacteriol. 191:4758-4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasegawa, M., H. Kishino, and T. Yano. 1985. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 22:160-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holden, M. T., Z. Heather, R. Paillot, K. F. Steward, K. Webb, F. Ainslie, T. Jourdan, N. C. Bason, N. E. Holroyd, K. Mungall, M. A. Quail, M. Sanders, M. Simmonds, D. Willey, K. Brooks, D. M. Aanensen, B. G. Spratt, K. A. Jolley, M. C. Maiden, M. Kehoe, N. Chanter, S. D. Bentley, C. Robinson, D. J. Maskell, J. Parkhill, and A. S. Waller. 2009. Genomic evidence for the evolution of Streptococcus equi: host restriction, increased virulence, and genetic exchange with human pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huson, D. H., and D. Bryant. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23:254-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huson, D. H., K. Reinert, S. A. Kravitz, K. A. Remington, A. L. Delcher, I. M. Dew, M. Flanigan, A. L. Halpern, Z. Lai, C. M. Mobarry, G. G. Sutton, and E. W. Myers. 2001. Design of a compartmentalized shotgun assembler for the human genome. Bioinformatics 17(Suppl. 1):S132-S139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaccard, P. 1908. Nouvelles recherches sur la distribution florale. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 44:223-270. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knight, S. D. 2007. Structure and assembly of Yersinia pestis F1 antigen. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 603:74-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kukleva, L. M., G. A. Eroshenko, V. E. Kuklev, N. Shavina, M. Krasnov Ia, N. P. Guseva, and V. V. Kutyrev. 2008. A study of the nucleotide sequence variability of rha locus genes of Yersinia pestis main and non-main subspecies. Mol. Gen. Mikrobiol. Virusol. 2008:23-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurtz, S., A. Phillippy, A. L. Delcher, M. Smoot, M. Shumway, C. Antonescu, and S. L. Salzberg. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lathem, W. W., P. A. Price, V. L. Miller, and W. E. Goldman. 2007. A plasminogen-activating protease specifically controls the development of primary pneumonic plague. Science 315:509-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leal-Balbino, T. C., N. C. Leal, C. V. Lopes, and A. M. Almeida. 2004. Differences in the stability of the plasmids of Yersinia pestis cultures in vitro: impact on virulence. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 99:727-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li, Y., Y. Cui, Y. Hauck, M. E. Platonov, E. Dai, Y. Song, Z. Guo, C. Pourcel, S. V. Dentovskaya, A. P. Anisimov, R. Yang, and G. Vergnaud. 2009. Genotyping and phylogenetic analysis of Yersinia pestis by MLVA: insights into the worldwide expansion of Central Asia plague foci. PLoS One 4:e6000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li, Y., E. Dai, Y. Cui, M. Li, Y. Zhang, M. Wu, D. Zhou, Z. Guo, X. Dai, B. Cui, Z. Qi, Z. Wang, H. Wang, X. Dong, Z. Song, J. Zhai, Y. Song, and R. Yang. 2008. Different region analysis for genotyping Yersinia pestis isolates from China. PLoS One 3:e2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medini, D., C. Donati, H. Tettelin, V. Masignani, and R. Rappuoli. 2005. The microbial pan-genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15:589-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mollaret, H. H., and C. Mollaret. 1965. Melibiose fermentation in the genus Yersina and its importance in the diagnosis of the varieties of Y. pestis. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. Filiales 58:154-156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Motin, V. L., A. M. Georgescu, J. M. Elliott, P. Hu, P. L. Worsham, L. L. Ott, T. R. Slezak, B. A. Sokhansanj, W. M. Regala, R. R. Brubaker, and E. Garcia. 2002. Genetic variability of Yersinia pestis isolates as predicted by PCR-based IS100 genotyping and analysis of structural genes encoding glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (glpD). J. Bacteriol. 184:1019-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagamatsu, T., H. Yamasaki, T. Hirota, M. Yamato, Y. Kido, M. Shibata, and F. Yoneda. 1993. Syntheses of 3-substituted 1-methyl-6-phenylpyrimido[5,4-e]-1,2,4-triazine-5,7(1H,6H)-diones (6-phenyl analogs of toxoflavin) and their 4-oxides, and evaluation of antimicrobial activity of toxoflavins and their analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 41:362-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson, K. E., R. A. Clayton, S. R. Gill, M. L. Gwinn, R. J. Dodson, D. H. Haft, E. K. Hickey, J. D. Peterson, W. C. Nelson, K. A. Ketchum, L. McDonald, T. R. Utterback, J. A. Malek, K. D. Linher, M. M. Garrett, A. M. Stewart, M. D. Cotton, M. S. Pratt, C. A. Phillips, D. Richardson, J. Heidelberg, G. G. Sutton, R. D. Fleischmann, J. A. Eisen, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, H. O. Smith, J. C. Venter, and C. M. Fraser. 1999. Evidence for lateral gene transfer between Archaea and bacteria from genome sequence of Thermotoga maritima. Nature 399:323-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parkhill, J., G. Dougan, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, D. Pickard, J. Wain, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. D. Bentley, M. T. Holden, M. Sebaihia, S. Baker, D. Basham, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, P. Connerton, A. Cronin, P. Davis, R. M. Davies, L. Dowd, N. White, J. Farrar, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, A. Haque, T. T. Hien, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, T. S. Larsen, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. O'Gaora, C. Parry, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a multiple drug resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi CT18. Nature 413:848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Parkhill, J., B. W. Wren, N. R. Thomson, R. W. Titball, M. T. Holden, M. B. Prentice, M. Sebaihia, K. D. James, C. Churcher, K. L. Mungall, S. Baker, D. Basham, S. D. Bentley, K. Brooks, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, T. Chillingworth, A. Cronin, R. M. Davies, P. Davis, G. Dougan, T. Feltwell, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, K. Jagels, A. V. Karlyshev, S. Leather, S. Moule, P. C. Oyston, M. Quail, K. Rutherford, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, K. Stevens, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Genome sequence of Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of plague. Nature 413:523-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Phillips, A. P., B. C. Morris, D. Hall, M. Glenister, and J. E. Williams. 1988. Identification of encapsulated and non-encapsulated Yersinia pestis by immunofluorescence tests using polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies. Epidemiol. Infect. 101:59-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prentice, M. B., K. D. James, J. Parkhill, S. G. Baker, K. Stevens, M. N. Simmonds, K. L. Mungall, C. Churcher, P. C. Oyston, R. W. Titball, B. W. Wren, J. Wain, D. Pickard, T. T. Hien, J. J. Farrar, and G. Dougan. 2001. Yersinia pestis pFra shows biovar-specific differences and recent common ancestry with a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 183:2586-2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rasko, D. A., G. S. Myers, and J. Ravel. 2005. Visualization of comparative genomic analyses by BLAST score ratio. BMC Bioinformatics 6:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sekowska, A., V. Denervaud, H. Ashida, K. Michoud, D. Haas, A. Yokota, and A. Danchin. 2004. Bacterial variations on the methionine salvage pathway. BMC Microbiol. 4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soler Bistué, A. J., D. Birshan, A. P. Tomaras, M. Dandekar, T. Tran, J. Newmark, D. Bui, N. Gupta, K. Hernandez, R. Sarno, A. Zorreguieta, L. A. Actis, and M. E. Tolmasky. 2008. Klebsiella pneumoniae multiresistance plasmid pMET1: similarity with the Yersinia pestis plasmid pCRY and integrative conjugative elements. PLoS One 3:e1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song, Y., Z. Tong, J. Wang, L. Wang, Z. Guo, Y. Han, J. Zhang, D. Pei, D. Zhou, H. Qin, X. Pang, Y. Han, J. Zhai, M. Li, B. Cui, Z. Qi, L. Jin, R. Dai, F. Chen, S. Li, C. Ye, Z. Du, W. Lin, J. Wang, J. Yu, H. Yang, J. Wang, P. Huang, and R. Yang. 2004. Complete genome sequence of Yersinia pestis strain 91001, an isolate avirulent to humans. DNA Res. 11:179-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Summers, D. K., C. W. Beton, and H. L. Withers. 1993. Multicopy plasmid instability: the dimer catastrophe hypothesis. Mol. Microbiol. 8:1031-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thomson, N. R., S. Howard, B. W. Wren, M. T. Holden, L. Crossman, G. L. Challis, C. Churcher, K. Mungall, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, T. Feltwell, Z. Abdellah, H. Hauser, K. Jagels, M. Maddison, S. Moule, M. Sanders, S. Whitehead, M. A. Quail, G. Dougan, J. Parkhill, and M. B. Prentice. 2006. The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. PLoS Genet 2:e206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Torrea, G., V. Chenal-Francisque, A. Leclercq, and E. Carniel. 2006. Efficient tracing of global isolates of Yersinia pestis by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis using three insertion sequences as probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:2084-2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Touchman, J. W., D. M. Wagner, J. Hao, S. D. Mastrian, M. K. Shah, A. J. Vogler, C. J. Allender, E. A. Clark, D. S. Benitez, D. J. Youngkin, J. M. Girard, R. K. Auerbach, S. M. Beckstrom-Sternberg, and P. Keim. 2007. A North American Yersinia pestis draft genome sequence: SNPs and phylogenetic analysis. PLoS One 2:e220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Touchon, M., C. Hoede, O. Tenaillon, V. Barbe, S. Baeriswyl, P. Bidet, E. Bingen, S. Bonacorsi, C. Bouchier, O. Bouvet, A. Calteau, H. Chiapello, O. Clermont, S. Cruveiller, A. Danchin, M. Diard, C. Dossat, M. E. Karoui, E. Frapy, L. Garry, J. M. Ghigo, A. M. Gilles, J. Johnson, C. Le Bouguenec, M. Lescat, S. Mangenot, V. Martinez-Jehanne, I. Matic, X. Nassif, S. Oztas, M. A. Petit, C. Pichon, Z. Rouy, C. S. Ruf, D. Schneider, J. Tourret, B. Vacherie, D. Vallenet, C. Medigue, E. P. Rocha, and E. Denamur. 2009. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welch, T. J., W. F. Fricke, P. F. McDermott, D. G. White, M. L. Rosso, D. A. Rasko, M. K. Mammel, M. Eppinger, M. J. Rosovitz, D. Wagner, L. Rahalison, J. E. Leclerc, J. M. Hinshaw, L. E. Lindler, T. A. Cebula, E. Carniel, and J. Ravel. 2007. Multiple antimicrobial resistance in plague: an emerging public health risk. PLoS One 2:e309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welkos, S. L., K. M. Davis, L. M. Pitt, P. L. Worsham, and A. M. Freidlander. 1995. Studies on the contribution of the F1 capsule-associated plasmid pFra to the virulence of Yersinia pestis. Contrib. Microbiol. Immunol. 13:299-305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wickstrum, J. R., J. M. Skredenske, A. Kolin, D. J. Jin, J. Fang, and S. M. Egan. 2007. Transcription activation by the DNA-binding domain of the AraC family protein RhaS in the absence of its effector-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 189:4984-4993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Williams, J. E., D. N. Harrison, T. J. Quan, J. L. Mullins, A. M. Barnes, and D. C. Cavanaugh. 1978. Atypical plague bacilli isolated from rodents, fleas, and man. Am. J. Public Health 68:262-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winter, C. C., W. B. Cherry, and M. D. Moody. 1960. An unusual strain of Pasteurella pestis isolated from a fatal human case of plague. Bull. W.H.O. 23:408-409. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Worsham, P. L., and C. Roy. 2003. Pestoides F, a Yersinia pestis strain lacking plasminogen activator, is virulent by the aerosol route. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 529:129-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wren, B. W. 2003. The yersiniae—a model genus to study the rapid evolution of bacterial pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1:55-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou, D., Z. Tong, Y. Song, Y. Han, D. Pei, X. Pang, J. Zhai, M. Li, B. Cui, Z. Qi, L. Jin, R. Dai, Z. Du, J. Wang, Z. Guo, J. Wang, P. Huang, and R. Yang. 2004. Genetics of metabolic variations between Yersinia pestis biovars and the proposal of a new biovar, microtus. J. Bacteriol. 186:5147-5152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhou, D., and R. Yang. 2009. Molecular Darwinian evolution of virulence in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 77:2242-2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.