Abstract

The objective of this paper was to study in vitro transfection of tendon cells and adherence of transfected cells to different tendon surfaces. Achilles tendon fibroblasts from 2-month-old New Zealand white rabbits were cultured to confluence, after which the cells were transfected by an adenovirus carrying either the β-galactosidase reporter gene or the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 50, 100, or 500. Two days later, the cells were transplanted onto the surfaces of rabbit Achilles, peroneus brevis, flexor profundus, and extensor longus tendons. The tendons were assessed by X-gal staining after 9 days, and by GFP fluorescence at 7, 14, and 21 days. Twenty percent to 50% of the treated cells stained for β-galactosidase at an MOI of 500. The GFP-labeled cells showed nearly 100% fluorescence at an MOI of 50. No positive cells were visible in the control group. The β-galactosidase and GFP-expressing cells remained viable for as long as 3 weeks. It is possible to introduce foreign genes into rabbit tendon cells, transplant the cells onto tendon surfaces, and maintain viability of the cell/tendon construct for several weeks.

Keywords: Tenocyte, Hyaluronic acid, Gene transfer

INTRODUCTION

Gene therapy is a rapidly expanding field of medicine that involves the transfer of genes to individuals for therapeutic purposes.3,7,14 Originally, gene therapy was developed for the treatment of heritable genetic diseases1; patients having a defective gene or lacking a certain gene could be supplied with a normal version of that gene to reverse the genetic defect. More recently, acquired diseases have also been considered for gene therapy. Oncologic, vascular, and infectious disorders are now the subjects of considerable gene therapy research.2,10,17 The musculoskeletal system could also benefit from gene therapy. Several laboratories have investigated the possibility of gene transfer to cartilage,6 synovium18 (as a possible cure for osteoarthritis), and ligaments7,9 (to improve healing after rupture). Gene transfer to tendon has been established in rabbits7 and chickens.11

In all of these cases, the adenovirus has been the vector of choice, due to the ease of preparation of high virus titers (>10 plaque-forming units (PFUs) per mL) as well as the ability of the adenovirus to efficiently transfect nondividing and dividing cells. A disadvantage of the adenovirus is that, although the virus is rendered replication-defective by the deletion of critical genes (whose sites are then replaced with the desired therapeutic genes), it can still elicit an immune response. Not only do transfected cells produce viral proteins that can be recognized by the host immune system,5,18,23,24 but the virus itself can also cause an inflammatory reaction.12,13 The leaky expression of late viral genes, by transcomplementation of E1a-like proteins in transduced cells, leads to direct activation of cytotoxic immune pathways following major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I presentation on the cell surfaces. Additional inflammatory/humoral immune responses are also activated by the presence of the viral particles themselves. These immune effects are increased with increasing viral load, emphasizing the importance of delivery systems with lower multiplicities of infection (MOIs). Viral protein production can be prevented by constructing an adenoviral vector in which the complete viral coding genome has been deleted and replaced by the gene of interest, retaining only the terminal sequences required to direct replication and packaging in vitro. These so-called “gutless” viruses do, however, require the presence of a helper virus.8 These vectors are currently under development.

This study investigates the possibility of introducing a foreign gene onto the tendon surface without exposing the tissue to a high viral load. This is done by in vitro transfection of tendon fibroblasts and subsequently transplantation of those cells onto the tendon surface. We also investigate differences between tendon cells derived from different tendon areas in their ability to be transfected by the adenovirus vector, and the effect of different marker genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Two-month-old New Zealand white rabbits were killed by overdose of intravenous pentobarbital. The rabbits were sacrificed as part of other experiments not involving the tendons. The Achilles (A) tendon, the proximal part of the peroneus brevis (PB) tendon, the extensor longus (EL) tendon (inside the knee), and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) tendon (where it wraps the ankle) were harvested. Attached paratenon or synovium were carefully dissected from the tendons. The FDP tendon was divided into two parts: a distal fibrocartilaginous segment and a more proximal segment without fibrocartilage. All tendon parts were minced into 2-mm pieces and placed in 100-mm tissue culture dishes, which contained Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; BioWhittaker) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Gibco). The tendon pieces were cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 until cells migrated from the tendon to the dish and reached full confluence. The cells were then trypsinized (trypsin 0.05%; Gibco) and subcultured in 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/well.

Cell Transfection

The Ad5-β-galactosidase and Ad2-GFP constructs used in this study were deleted in the E1 and nonessential E3 regions, making them replication-deficient in cells other than HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney) cells or other E1-complementing cell lines. The E1 region was replaced in both constructs by either the bacterial LacZ (Ad5-β-galactosidase construct) gene or the jellyfish GFP (green fluorescent protein) gene (Ad2-GFP construct), both driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter.

To establish the MOI required for optimal transfection by Ad-LacZ of the different tendon cells, the cell monolayers were covered one night after plating with 300 μL serum-free DMEM containing different concentrations of the virus. The different concentrations chosen were MOIs of 500, 50, 5, 0.5, and 0. The cell cultures were at approximately 70% confluence when transfected. Following transfection, the cells were incubated overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. After 2 days, the cells were stained for β-galactosidase expression with X-gal using standard methods.

To establish the MOI of the Ad2-GFP construct, only Achilles tendon fibroblasts were incubated as described above, again at MOIs of 500, 50, 5, 0.5, and 0. GFP expression was assessed after 2 days under a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Cell Transplantation to Tendon Surfaces

LacZ-transfected cells

Tendon fibroblasts were obtained from the Achilles tendon as described above and subcultured in 24-well plates at 5.104 cells/well. One night after plating, the cells were transfected with Ad-β-galactosidase at an MOI of 500. The cells were trypsinized (trypsin 0.05%; Gibco) after 2 days, counted on a hemocytometer, and spun down at 1100 g. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Four different tendons - Achilles (A), peroneus brevis (PB), flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) with and without fibrocartilage, and extensor longus (EL) - were covered with a 40-μL film of medium containing 5 × 105 cells. After 45 minutes, the tendons were covered with medium. After 9 days of incubation, the tendons and the dish were washed with saline solution and then fixed in glutaraldehyde and stained for β-galactosidase expression with X-gal (Fig. 1).

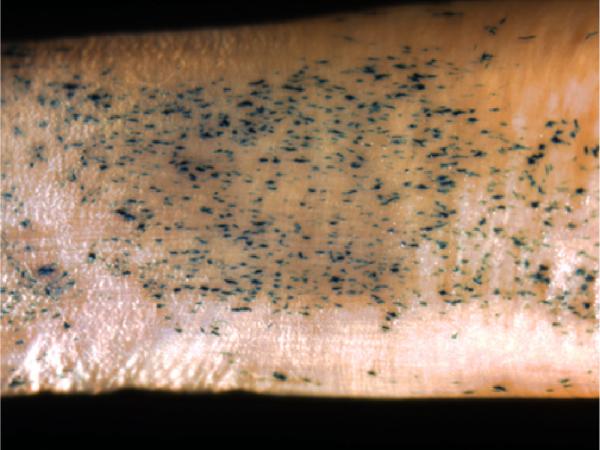

Fig. 1.

β-galactosidase staining on tendon surface (×40). Transfected cells stain blue.

GFP-transfected cells

Tendon fibroblasts were obtained from the Achilles tendon as described above and subcultured in 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/well. One night after plating, the cells were transfected with Ad-GFP at an MOI of 50. The cells were trypsinized (trypsin 0.05%; Gibco) after 2 days, counted on a hemocytometer, and spun down at 1100 g. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS to 5 × 105 cells/mL. The four different tendons (A, PB, FDP, and EL tendons) were each placed in a 0.5-mL tube containing the cell suspension. The tubes were taped to the cap of a roller bottle and mounted on a roller bank rotating at 1 rpm (Fig. 2). After incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 1 hour, the tendons were cultured for another 3 weeks in six-well plates. The tendons were photographed after 1 hour, 12 hours, 1 week, and 3 weeks (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Roller device method.

Fig. 3.

Roller bank cells with GFP staining after 1, 7, and 21 days (confocal fluorescent microscopy, ×100). Transfected cells fluoresce green. A: Achilles tendon; FDP: flexor digitorum profundus tendon.

RESULTS

An MOI of 500 of the Ad5-β-galactosidase construct was needed in all five groups of tendon fibroblasts to obtain staining in an adequate amount of cells. The percentage of cells staining positive for β-galactosidase ranged from 20% in the Achilles fibroblasts to 54% in the extensor longus fibroblasts (Table 1). At lower MOIs, few transfected cells were observed under the staining protocol applied. The control group showed no stained cells (data not shown). In contrast, as determined by the fluorescence assay, the Ad2-GFP construct was able to transfect 100% of the cells of each type at an MOI of 50, again with no cells showing fluorescence in the control group.

Table 1.

Results of Cell Transfection.

| Tendon | Turning Point (all at MOI of 500) |

|---|---|

| Achilles fibroblasts | 20.2% |

| FDP tension fibroblasts | 21.2% |

| PB fibroblasts | 30.3% |

| FDP “fibrocartilage” cells | 33.4% |

| EL fibroblasts | 54.2% |

Cell transplantation in the Ad5-β-galactosidase group showed that most cells were pulled by gravity to the floor of the dish. Only a few cells attached to the tendon (1 cell/mm2 tendon surface) (Table 2), except in the FDP tendon, where a fluid meniscus could be made due to the flat shape of the tendon and cells could not escape; this tendon showed 30 cells/mm2 attached in this specific area. Incubating the tendons in tubes on a rocker for different incubation times and rocking frequencies did not improve the transplantation rate (data not shown).

Table 2.

Results of Transplantation of Transfected Cells on Tendon Surface.

| Tendon | Cell Concentration |

|---|---|

| PB | 0.8 cells/mm2 |

| PB | 0.9 cells/mm2 |

| FDP | 30 cells/mm2 |

| Achilles | Abnormal distribution, with 2 or 3 spots with a high concentration of cells that overlapped (and therefore were impossible to count), while the rest of the tendon was blank |

| Control group | 0 cells/mm2 |

In contrast to the results with simple tendon immersion and the rocker method, cell transplantation of the GFP-infected cells using the roller bank showed cells attached to the whole surface area of the tendons. After 1 hour, the cells were round in appearance and could easily be removed by washing or careless handling; after overnight incubation, the cells assumed a flat shape and could not be removed by washing. The high concentration of fluorescent cells resulted in great overlap of the individual cells in most areas. This made accurate cell counting impossible. Gross examination of the tendons showed a slightly greater fluorescence on the larger tendons (Achilles and FDP) compared to the smaller tendons (EL and PB). There seemed to be no difference in the amount of cells attached between tendons of extrasynovial origin (i.e. tendons with paratenon, but no synovial tendon sheath or epitenon, e.g. PB and Achilles tendons) and tendons of intrasynovial origin (i.e. tendons without paratenon, but with epitenon and a sheath, e.g. FDP and EL tendons). There was a differentiation in orientation of the cells on the surfaces of tendons, based on tendon type. On extrasynovial tendons, the cells were randomly oriented; while on intrasynovial tendons, especially the epitendinous gliding surface of the FDP tendon, the cells tended to orient along the longitudinal axis of the tendon. Over time, the tendons slowly lost the GFP-expressing cells, so that after 3 weeks most of the fluorescent cells had disappeared from the tendon.

Encouraged by these results, we attempted the transfection of a functional gene, mouse hyaluronan synthase. Preliminary data using a red blood cell exclusion assay suggests that we have been able to transfect tendon cells successfully with this gene, and that hyaluronate is produced after transfection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Hyaluronan synthase transfection as demonstrated by red blood cell (RBC) exclusion. (a) Control. Note the RBC cover tendon fibroblasts. (b) RBC exclusion in a halo around transfected cells. (c) Halo effect abolished by treatment with hyaluronidase. (All ×400.)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have demonstrated a method to introduce an exogenous gene to the whole surface area of a tendon without exposing the tendon itself to a high viral load. Gene expression on the tendon surface persisted, at a declining rate, for at least 3 weeks. We have also shown evidence that potentially therapeutic genes can be transferred to tendon cells using this method.

The Ad2-GFP construct appeared to be a more efficient vector in our hands. Not only was a lower MOI needed, but all of the cells also showed GFP expression. It must be noted though that GFP fluorescence might be a more sensitive marker than β-galactosidase staining, and it might also be possible that cytoplasmic GFP persists in both daughter cells after cell division. Thus, the difference in apparent transfection efficiency between LacZ and GFP may be related to the efficiency of the detection method and not to a difference in actual transfection rates. For further experimentation, the Ad2-GFP vector was used because the tendons could be observed and photographed over time, without the need for fixation and staining to monitor the transfected cells.

The fluid-film method proved to be an inefficient way to seed cells on a tendon. The roller method seems clearly preferable, and we plan to use it in future experiments.

Injury to flexor tendons occurs primarily in children and young adults, so the socioeconomic impact is particularly important.16 The lengthy rehabilitation only adds to this burden. Most commonly, tendon injuries can be repaired directly.4 In more severe cases, tendon function may be replaced by the use of a tendon graft.22 Extrasynovial tendons, such as the palmaris longus tendon, are commonly used as the graft source to replace injured flexor tendons because of their similar size and caliber and minimal donor site function loss, but there is a difference in healing potential between intrasynovial and extrasynovial tendons after grafting. Extrasynovial tendons lack an epitenon layer and instead have a covering of loose paratenon tissue.19,20 Extrasynovial tendon healing results in increased gliding resistance and adhesion formation after tendon grafting,15,19–21 as compared to intrasynovial tendons.

While many methods have been investigated to prevent adhesion after tendon surgery, early mobilization has been proven to be the most effective. This method is less useful after tendon grafting,19,20 perhaps because tendon grafts must revascularize, and early motion may interfere with the revascularization process. Thus, methods that might reduce adhesions without requiring early motion are particularly attractive in cases where tendon grafting might be required.

Most adhesions after tendon grafting occur within the first few weeks. We believe that the method of cell transfection, with subsequent transfer to the tendon surface, may be useful in preventing adhesion formation after tendon grafting in this critical early phase. In such cases clinically, the tendon graft is removed from one location and placed in a new host bed. It could be possible to perform instead, as a preliminary step, harvesting of tendon cells from the patient, with subsequent transfection with a gene or genes of choice. Instead of a marker gene, the cells could carry a therapeutic gene encoding a growth factor, a growth factor inhibitor, or a lubricant such as hyaluronic acid. In this way, the patient's own cells can be used as a drug delivery system, reducing the risk of an immune response. Once the cells are transfected and functional, in a second step the graft could be harvested and the transfected cells transferred to the graft surface. In a third step, a standard tendon grafting procedure could be performed using the genetically modified graft.

This method does have some drawbacks compared to direct transfection of a tendon with the adenoviral vector. An initial, although small, operation would be needed to harvest cells for culture. After harvesting the tendon graft in a second procedure, overnight incubation would be needed to anchor the cells firmly to the tendon and prevent loss of the transfected cells after grafting. As most donor tendons are subcutaneous in location, these first two operations could be performed under brief local anesthesia. A third operation would be needed to graft the tendon the next day. Although two extra operations are an extra burden for the patient, the potential for decreased inflammatory reaction as compared to direct tendon transfection, coupled with the possibility of decreased adhesion formation from effective gene therapy, might justify this added burden.

In summary, we have shown that a variety of functional genes can be transferred to tendon cells in vitro using an adenoviral vector, and that these cells can be subsequently transferred to a tendon surface, where they appear to adhere. We believe that this method presents an opportunity to develop genetically modified tendon grafts which may find clinical applicability.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by grant AR44391, awarded by the National Institutes of Health. The authors gratefully acknowledge John McDonald, PhD, Mayo Clinic Scottsdale, for providing the adenoviral vector for the mouse hyaluronan synthase; and Richard Vile, PhD, Mayo Clinic Rochester, for the Ad5-β-galactosidase and Ad2-GFP constructs used in this study.

References

- 1.Anderson WF. Prospects for human gene therapy. Science. 1984;226:401–409. doi: 10.1126/science.6093246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bainbridge JW, Mistry AR, Thrasher AJ, Ali RR. Gene therapy for ocular angiogenesis. Clin Sci. 2003;104:561–575. doi: 10.1042/CS20020314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonadio J. Tissue engineering via local gene delivery. J Mol Med. 2000;78:303–311. doi: 10.1007/s001090000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer MI, Strickland JW, Engles D, Sachar K, Leversedge FJ. Flexor tendon repair and rehabilitation: State of the art in 2002. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:137–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engelhardt JF, Ye X, Doranz B, Wilson JM. Ablation of E2A in recombinant adenoviruses improves trans-gene persistence and decreases inflammatory response in mouse liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6196–6200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans C, Robbins PD. Prospects for treating arthritis by gene therapy. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:779–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerich TG, Kang R, Fu FH, Robbins PD, Evans CH. Gene transfer to the rabbit patellar tendon: Potential for genetic enhancement of tendon and ligament healing. Gene Ther. 1996;3:1089–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardy S, Kitamura M, Harris-Stansil T, Dai Y, Phipps ML. Construction of adenovirus vectors through Cre-lox recombination. J Virol. 1997;71:1842–1849. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1842-1849.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hildebrand KA, Deie M, Allen CR, Smith DW, Georgescu HI, Evans CH, Robbins PD, Woo SL. Early expression of marker genes in the rabbit medial collateral and anterior cruciate ligaments: The use of different viral vectors and the effects of injury. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:37–42. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang EM, De Witte M, Malech H, Morgan RA, Carter C, Leitman SF, Childs R, Barrett AJ, Little R, Tisdale JF. Gene therapy-based treatment for HIV-positive patients with malignancies. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2002;11:809–816. doi: 10.1089/152581602760404612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lou J, Manske PR, Aoki M, Joyce ME. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer into tendon and tendon sheath. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:513–517. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarter SD, Scott JR, Lee PJ, Zhang X, Choi AM, McLean CA, Badhwar A, Dungey AA, Bihari A, Harris KA, Potter RF. Cotransfection of heme oxygenase-1 prevents the acute inflammation elicited by a second adenovirus. Gene Ther. 2003;10:1629–1635. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCoy RD, Davidson BL, Roessler BJ, Huffnagle GB, Janich SL, Laing TJ, Simon RH. Pulmonary inflammation induced by incomplete or inactivated adenoviral particles. Hum Gene Ther. 1995;6:1553–1560. doi: 10.1089/hum.1995.6.12-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mi Z, Ghivizzani SC, Lechman E, Glorioso JC, Evans CH, Robbins PD. Adverse effects of adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of human transforming growth factor beta 1 into rabbit knees. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R132–R139. doi: 10.1186/ar745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Momose T, Amadio PC, Sun YL, Zhao C, Zobitz ME, Harrington JR, An KN. Surface modification of extrasynovial tendon by chemically modified hyaluronic acid coating. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:219–224. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newmeyer W. History of the Journal of Hand Surgery. J Hand Surg [Am] 2000;25:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandha HS, Martin LA, Rigg AS, Ross P, Dalgleish AG. Oncological applications of gene therapy. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;1:122–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roessler BJ, Allen ED, Wilson JM, Hartman JW, Davidson BL. Adenoviral-mediated gene transfer to rabbit synovium in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1085–1092. doi: 10.1172/JCI116614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seiler JG, 3rd, Chu CR, Amiel D, Woo SL, Gelberman RH. The Marshall R. Urist Young Investigator Award. Autogenous flexor tendon grafts. Biologic mechanisms for incorporation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(345):239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seiler JG, 3rd, Gelberman RH, Williams CS, Woo SL, Dickersin GR, Sofranko R, Chu CR, Rosenberg AE. Autogenous flexor-tendon grafts. A biomechanical and morphological study in dogs. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1993;75:1004–1014. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199307000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchiyama S, Amadio PC, Coert JH, Berglund LJ, An KN. Gliding resistance of extrasynovial and intrasynovial tendons through the A2 pulley. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1997;79:219–224. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199702000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson S, Sammut D. Flexor tendon graft attachment: A review of methods and a newly modified tendon graft attachment. J Hand Surg [Br] 2003;28:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0266-7681(02)00362-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, Furth EE, Gonczol E, Wilson JM. Cellular immunity to viral antigens limits E1-deleted adenoviruses for gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y, Nunes FA, Berencsi K, Gonczol E, Engelhardt JF, Wilson JM. Inactivation of E2a in recombinant adenoviruses improves the prospect for gene therapy in cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 1994;7:362–369. doi: 10.1038/ng0794-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]