Abstract

The study aim is to explore the results of an HIV stigma intervention in five African health care settings. A case study approach was used. The intervention consisted of bringing together a team of approximately 10 nurses and 10 people living with HIV or AIDS (PLHA) in each setting and facilitating a process in which they planned and implemented a stigma reduction intervention, involving both information giving and empowerment. Nurses (n = 134) completed a demographic questionnaire, the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument-Nurses (HASI-N), a self-efficacy scale, and a self-esteem scale, both before and after the intervention, and the team completed a similar set of instruments before and after the intervention, with the PLHA completing the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument for PLHA (HASI-P). The intervention as implemented in all five countries was inclusive, action-oriented, and well received. It led to understanding and mutual support between nurses and PLHA and created some momentum in all the settings for continued activity. PLHA involved in the intervention teams reported less stigma and increased self-esteem. Nurses in the intervention teams and those in the settings reported no reduction in stigma or increases in self- esteem and self-efficacy, but their HIV testing behavior increased significantly. This pilot study indicates that the stigma experience of PLHA can be decreased, but that the stigma experiences of nurses are less easy to change. Further evaluation research with control groups and larger samples and measuring change over longer periods of time is indicated.

Introduction

Over the last 5 years, a team of African and U.S. researchers has studied HIV stigma intensively in five African countries. We started with a qualititative study based on focus group interviews to understand HIV stigma from the perspectives of nurses1,2 and those living with HIV infection3–7 and then developed two instruments to measure HIV stigma in the African context4,8. We then used these two instruments to monitor HIV stigma over the period of 1 year in all five countries, in a group of people living with HIV infection and a group of nurses.9

We found that perceived stigma was higher in certain countries and settings than in others and that, although it decreases over time, it still remains a serious problem for people living with HIV.10 We also found that this stigma is higher for people who are on antiretrovirals (ARVs) than for those not on ARVs (Makoae, Uys, Dlamini et al. Unpublished). It is inevitable that we eventually asked ourselves: “What can be done to address HIV stigma?” This article describes the intervention we designed, and the results we obtained when implementing it in a health care setting in each of the five countries.

Background

In 2003, Brown et al.11 published a review of the literature on HIV/AIDS stigma interventions. They limited their review to articles published in peer-reviewed journals since 2001 evaluating stigma interventions through experimental or quasi-experimental design.

Of the such studies they included, 16 of were conducted in developed countries, 1 in Thailand, and the rest (5) in Africa. In our literature review we found an additional 15 articles, but we included articles earlier than 2001 and articles from other illnesses, such as leprosy and cancer, mainly to update the review and to include the rich disease stigma literature outside of HIV and AIDS. In many of the articles reviewed, the stigma reduction behavior or intervention was measured for a period of less than 12 months and used information sessions as an intervention.12

The aims of the interventions differed greatly across the studies and most of the studies did not have the reduction of HIV stigma as its exclusive aim. Brown et al.11 classified the aims of the interventions they found in their 22 studies as follows:

Increasing tolerance of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA) among certain groups in the general population (14 studies);

Increasing willingness to engage with PLHA among health care providers (3 studies);

Improving the coping strategies for dealing with HIV stigma in those as risk of such stigma.

These aims influenced the instruments used to evaluate the success of the intervention. In the case of the first group, self-developed attitude scales were the most common measure, while the second group mainly used an instrument that measures “fear of treating PLHA” and “equal treatment for PLHA”.11 The last group of studies used psychological measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory, and anxiety and coping measures. In the additional articles we reviewed, we found a number of other instruments used to measure variables other than stigma and a number of indirect measures of stigma. These included the P scale, which measures engagement with social events13, and a number of self-developed scales, for instance the Fife and Wright14 Social Impact Scale. The only direct measures of stigma we found used in the 15 articles we reviewed was Sowell et al.'s Stigma and Disclosure Scale.15

The nature and success of the interventions are difficult to evaluate because of mixed interventions and varied duration (from a single 15- to 20-minute education unit16 to an 8-week psycho-educational group intervention17 and varied strategies. The settings, scales, and timing of measurement differed across the studies. We summarize the findings as follows:

Tolerance of PLHA in the general population can be changed by a range of interventions in the short term, but longer term impact has not been studied.

Sometimes the changes were not great, and a range of negative attitudes remained in place.

Attitudes of health workers can be changed in a positive direction, but fear of infection remains high.

Testing, disclosure and ARV medication behavior among PLHA improves after an intervention aimed at strengthening their own coping behavior, but anxiety remains high.

These findings are encouraging in that interventions can reduce stigma. However, many of these reports did not include a validated instrument to measure change in stigma over time.

Stigma Reduction Intervention

Our intervention consisted of bringing a group of PLHA and nurses from one health setting together for a 2-day project initiation workshop. The project initiation workshop was facilitated by a nurse and PLHA based on a standard manual and both were trained over a period of 2 days prior to them running the workshops. On the basis of this training the teams were then given the task of designing, implementing, and evaluating a project to reduce stigma in their health care setting within a month, with the support of the facilitators. The project concluded with a 1-day project evaluation workshop again facilitated by the facilitators. The projects were not standardized and the project undertaken in each of the five settings and report on the impact of the project on the participants combined as a group will be described later.

We used Goffman's18 definition of stigma, which is an undesirable or discrediting attribute that an individual possesses, which affects the person's status in society. We developed a model of the HIV stigma process19 which indicates that internal stigma, defined as thoughts and behavior stemming from the person's own negative perceptions about themselves based on their HIV status, is an important component of HIV stigma (p. 547). In this model the health care system is identified as a setting in which HIV stigma is both triggered and manifested. From the beginning of our study, we have been working with nurses as well as with PLHA and we have believed strongly that antistigma interventions should start with health facilities for two reasons. First, PLHA are dependent on these facilities for their health care. If they are stigmatized in these facilities, this forms a potential barrier to care and support. Second, health care workers are opinion leaders in their own communities. If they stigmatize PLHA, they set an example that is difficult to counteract. The health care setting was also targeted by Mahendra et al.20 in India in their study to reduce HIV stigma. We focused the intervention on a single health care facility in each country as a pilot study for a larger trial.

We chose an intervention that combined three strategies: (1) sharing information, (2) increasing contact with the affected group, and (3) improving coping through empowerment.

Sharing information consisted of providing the results of the previous phases of our study and giving general information about the impact of stigma on PLHA. Increasing contact consisted of bringing together 10 nurses from a particular health care facility and 10 PLHA that frequent the same facility to plan a stigma reduction intervention together. We constructed a new context that attempted to equalize the relationship between health service providers and service users. This promoted empathy, changed roles, and facilitated the development of new perspectives on the issues. Empowerment involved engaging PLHA in an activity that saw them addressing stigma directly, and not accepting it or living with it.

We saw this as empowering, in that it gives the PLHA the feeling that he or she can do something positive, and is not merely a victim. It also made them “service providers” and not only service users, again accentuating a positive, active involvement. We adopted the definition of empowerment by Cross and Choudhary13 who wrote “the process of empowerment is one in which identity is established, the value of life is enhanced and the potential for a dynamic future is constructed” (p. 317). Our empowerment strategy also has some commonalities with the coping interventions described by Chesney et al.21, Puhl and Brownell22, and Gordon-Garofalo and Rubin.17

Based on all these considerations, we developed a manual to be used by a nurse facilitator and a PLHA facilitator to run the intervention workshops. It contained 11 topics that included presentations and exercises as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Topics for Intervention Workshops

| Session | Topic |

|---|---|

| 1 | What is HIV/AIDS stigma? Understanding and defining stigma |

| 2 | The outcomes of stigma |

| 3 | Coping with stigma |

| 4 | Why is stigma hard to change? |

| 5 | Identifying stigma interventions and local examples |

| 6 | Evaluating options for action |

| 7 | Planning for change |

| 8 | Choosing project options |

| 9 | Planning the project |

| 10 | Vision, aim and objectives |

| 11 | Task analysis and action plan |

The manual outlined the process to be followed, the objectives to reach in each section, the participatory activities to be used, and any content to be covered. It was emphasized that facilitators should adapt the presentations to local needs and conditions prior to using it in the workshops. They were also asked to document every step taken, writing workshop reports, and keeping minutes of all further meetings.

We consider the 3 days spent in the project initiation and the project evaluation workshops as well as all the time they spent together in the planning and intervention as the contact component of the intervention. It should be noted that our intervention is the creation of this team and their implementation of their project. It is not the individual projects the teams planned and implemented. Team members were not paid, but provision was made for a limited amount of expenditure to be covered, such as their travel cost.

Methodology

Study questions

What was the impact of participating in the stigma reduction intervention at a health setting level upon the nurse and PLHA participants (the team)?

What projects were undertaken by each site and what were the outcomes of those projects?

Research design

A multiple-case study design22 was used to describe the intervention in five health care settings in five African countries (Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland, and Tanzania). The intervention at a single health care facility is seen as a case, and the case study protocol consisted of the following components:

Intervention team description (report by facilitators).

Duration of contact (report by facilitators and intervention team).

Team project (report by facilitators and intervention team).

Pretest and posttest data of teams (nurses and PLHA) (pretest and posttest measurement).

Evaluation of project by the team (report by intervention team and facilitators).

The three sources of the data used for each case study are indicated in parentheses for each component.

The construct validity of the study design was enhanced by using multiple sources of data and the reliability was enhanced by using a case study protocol. External validity was promoted by using five case studies.22

Sampling

Country and site

The five countries were chosen based on the high level of HIV and AIDS prevalence, varying from 18.1% to 26.1% (UNAIDS Report, 2008). The intervention sites were conveniently chosen by researchers based on accessibility and willingness to participate.

The intervention team

We brought the group of approximately 10 nurses and 10 PLHA (the team) together. The nurses were identified by the nurse managers of their facilities as being interested in or involved with HIV/AIDS care, and the PLHA were identified by support groups active in the area.

Data collection

Qualitative data

The facilitators wrote a report after their 2-day workshop and again after the implementation of the project and the concluding 1-day workshop. This addressed components 1, 2, 3, and 5 of the case protocol. The intervention team also submitted a written report on their intervention, which addressed components 2, 3, and 5. All these reports were submitted within 2 weeks of the final workshop day. Finally opinion leaders from the clinical setting in which the intervention was conducted were interviewed using a semistructured interview guide. The intention of the interview was to assess whether the key informants from the clinical setting noticed a change in the attitudes and behavior regarding HIV related stigma.

Quantitative data

In each of the five sites pretest and posttest measurements were conducted with the nurses and PLHA in the intervention team, using a range of instruments. This was done within 3 months prior to the intervention and within 1 month of the completion of the intervention. The total period of data collection was 6 months.

Instruments

The following five instruments were used in the study:

Demographic Questionnaire: The Demographic Questionnaire was used to obtain demographic, job-, and illness-related information from the nurses and PLHA.

HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument–Nurse (HASI-N) (Uys et al, In Press): a 19-item self-administered instrument comprising two factors (nurses stigmatizing patients and nurses being stigmatized) with an overall Cronbach α of 0.90. Concurrent validity was tested by comparing the level of stigma with job satisfaction and quality of life. The HASI-N was inductively derived and measures the stigma experienced and enacted by nurses. Project team member nurses and the 50 nurses completed this scale.

HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument–PLWA (HASI-P):4 a 33-item instrument that measures 6 dimensions of HIV-related stigma (verbal abuse, negative self-perception, health care neglect, social isolation, fear of contagion, workplace stigma), and total perceived stigma. The Cronbach α reliability coefficients for the scale scores range from 0.76 to 0.90. PLHA on the project teams completed this scale. This questionnaire can be self- administered or can be done by interview in the case of respondents with limited literacy.

Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale:23 used to measure the participant's generalized self efficacy. The original 10-item scale aims to measure self-beliefs of individuals to cope with a variety of difficult demands in life. In this study an additional item which aimed to measure the stigma the person experiences was added. The Cronbach α reliability for the scale ranged from 0.80–0.91.

Self-Esteem Scale:24 a 10- item instrument used to measure global self-esteem. The items range from overall feelings of self-worth to self-acceptance. The Cronbach α reliability for the scale ranged from 0.62–0.72.

Self-evaluation of intervention

A Likert scale self-report questionnaire was administered to all team participants at the end of the intervention. Three broad questions assessing their satisfaction in the process, implementation of the intervention plan, and their opinion of the purpose of the intervention were asked.

Data management and analysis

Responses to the questionnaires were entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows Version 15.0 software (SPSS, 2007).

Descriptive statistics (i.e., means, standards deviations, frequencies, and percentages) and paired t tests were used to test group differences.

Protection of human subjects

The research protocol was approved by all seven of the universities involved (see author's list), providing protection of human subjects. Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the appropriate local and central government authorities. Participants were provided with information about the background of the study and informed that information was voluntary and that they may withdraw from participating at any time. Participants were also assured of confidentiality of information obtained, following this explanation participants each signed a written consent form. Participants were consented and the surveys conducted in either English or the local languages of the five countries.

Results

Sample description

Intervention teams

The average age of participants in the five intervention teams (n = 84) was 37.9 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.8) and 79.8% (n = 67) were female. The participants were from the following five countries, Lesotho 16.6% (n = 14), Malawi 21.4% (n = 18), South Africa 20.2% (n = 17), Swaziland 17.8% (n = 15) and Tanzania 23.8% (n = 20). Table 2 describes the health care settings targeted in the different countries and the intervention teams.

Table 2.

Descriptions by Country of Site, Team Members, Setting Nurses, and Stigma Reduction Interventions

| Country | Sites | Team PLHA n = 41 | Team nurses n = 43 | Setting nurses n = 134 | Duration of intervention | Project impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesotho | Periurban hospital, with 6 linked clinics (120 beds). Has an ARV center. | 7 (4 female) | 7 (5 female) | 19 (18 female) | Workshop: 21 hours Meetings: 5 hours. Intervention: 8 hours Total: 35 hours | Intervention led to similar activities involving health care workers and PLHAs being hosted regularly. |

| Malawi | Regional referral hospital (300 beds) | 10 (5 female) | 8 (all female) | 43 (36 female) | Workshop: 21 hours Meetings: 13 hours Intervention: 10 hours Total: 44 hours | Intervention repeated at neighbor hospital. Planning to take it to other venues. Continued combined training of nurses and PLHA |

| South Africa | Regional referral hospital (335 beds) | 7 (6 female) | 10 (all female) | 46 (41 female) | Workshop: 21 hours Meetings: 5 hours Intervention: 17 hours Total: 43 hours | Two support groups started. Program taken as theme for World AIDS Day 2007. |

| Swaziland | Regional referral hospital (250 beds) | 7 (6 female) | 8 (7 female) | 11 (8 female) | Workshop: 21 hours Meetings: 5 hours Intervention: 10 hours Total: 36 hours | Greater involvement of community leaders including traditional healers involvement in HIV stigma programs. |

| Tanzania | Municipal hospital ( 200 beds) | 10 (6 female) | 10 (9 female) | 15 (13 female) | Workshop: 21 hours Meetings: 8 hours Intervention: 20 hours Total: 49 hours | Intervention to be carried out in the neighboring district hospitals in Dar es Salaam. |

PLHA, people living with HIV or AIDS; ARV, antiretroviral.

Study question 1

What was the impact of participating in the stigma reduction intervention at a health setting level upon the nurse and PLHA team members?

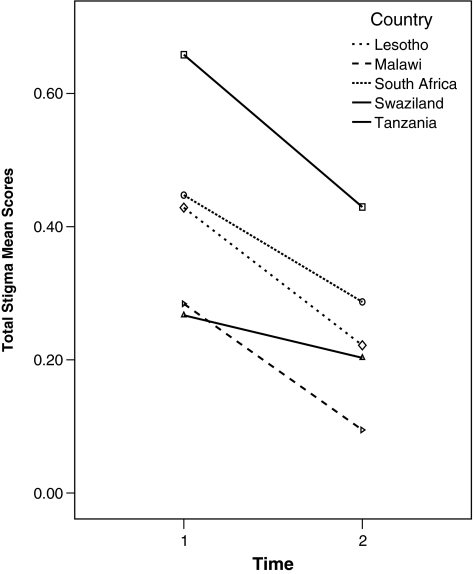

PLHA (Table 3) who participated in the project showed a significant reduction in overall perceived stigma (t = 3.16, df = 40 p = 0.003). They also reported a significant reduction in workplace stigma (t = 2.55, df = 40, p = 0.015) and negative self perception (t = 4.30, df = 40, p = 0.001). Their self esteem changed significantly (t = 2.57, df = 40, p = 0.014), but not their self efficacy.

Table 3.

People Living with HIV/AIDS Team Members Pretest and Posttest Results (n = 41)

| Pretest | Posttest | Paired t test | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigma | |||||

| Verbal abuse | Mean = 0.54 (SD = 0.75) | Mean = 0.43 (SD = 0.67) | 0.97 | 40 | 0.38 |

| Self-perception | Mean = 0.82 (SD = 0.93) | Mean = 0.36 (SD = 0.67) | 4.30 | 40 | ≤0.001 |

| Neglect | Mean = 0.13 (SD = 0.42) | Mean = 0.06 (SD = 0.12) | 1.20 | 40 | 0.237 |

| Isolation | Mean = 0.39 (SD = 0.72) | Mean = 0.33 (SD = 0.69) | 0.66 | 40 | 0.510 |

| Fear of contagion | Mean = 0.25 (SD = 0.50) | Mean = 0.17 (SD = 0.45) | 1.08 | 40 | 0.285 |

| Workplace stigma | Mean = 0.46 (SD = 0.85) | Mean = 0.15 (SD = 0.48) | 2.55 | 40 | 0.015 |

| Total score | Mean = 0.42 (SD = 0.48) | Mean = 0.25 (SD = 0.35) | 3.16 | 40 | 0.003 |

| Self-efficacy | Mean = 34.05 (SD = 9.29) | Mean = 36.76 (SD = 7.03) | 1.64 | 40 | 0.11 |

| Self-esteem | Mean = 19.46 (SD = 4.54) | Mean = 21.58 (SD = 4.44) | 2.57 | 40 | 0.014 |

SD, standard deviation.

Nurses who participated on the intervention teams (Table 4) demonstrated no change in stigma but a significantly higher percentage of the nurse were tested for HIV by the end of the project (χ2 = 12.18, df = 1, p ≤ 0.001). There was no significant difference in self-esteem or self-efficacy scores of this group before and after the intervention.

Table 4.

Nurses Pretest and Posttest Results: Intervention Team and Setting Nurses

| Variable | Pretest | Posttest | Test | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses in intervention teams (n = 43) | |||||

| Been for HIV test | 79.1% (n = 34) | 93.0% (n = 40) | χ2 = 12.18 | 1 | ≤0.001 |

| Stigma | Mean = 0.71 (SD = 0.38) | Mean = 0.73 (SD = 0.50) | t = 0.20 | 42 | 0.84 |

| Total score | |||||

| Nurse stigmatizing behavior | Mean = 0.46 (SD = 0.46) | Mean = 0.39 (SD = 0.43) | t = 0.91 | 42 | 0.37 |

| Community stigmatizing behavior | Mean = 1.00 (SD 0.63) | Mean = 1.10 (SD = 0.83) | t = 0.78 | 42 | 0.44 |

| Self-efficacy | Mean = 35.02 (SD 5.77) | Mean = 36.49 (SD 6.09) | t = 1.28 | 42 | 0.21 |

| Self-esteem | Mean = 19.71 (SD 4.74) | Mean = 21.32 (SD 3.92) | t = 1.79 | 42 | 0.08 |

| Nurses in settings (n = 134) | |||||

| Been for HIV | 116 (86.6%) | 125 (93.3%) | χ2 = 34.35 | 1 | ≤0.001 |

| Stigma | Mean = 0.45 (SD = 0.47) | Mean = 0.46 (SD = 0.45) | t = 0.24 | 133 | 0.812 |

| Total score | |||||

| Nurse stigmatizing behavior | Mean = 0.24 (SD = 0.41) | Mean = 0.24 (SD = 0.41) | t = 0.01 | 133 | 0.992 |

| Community stigmatizing behavior | Mean = 0.69 (SD = 0.72) | Mean = 0.71 (SD = 0.68) | t = 0.34 | 133 | 0.733 |

SD, standard deviation.

Study question 2

What projects were undertaken by each site and what were the outcomes of those projects?

All the projects combined the aims of increasing acceptance of PLHA among both health care workers and the population at large and increasing the willingness of health care providers to care for PLHA. According to the categories suggested by Brown et al.11, all the teams chose to implement information based, skills building, and contact interventions, although the actual interventions differed greatly. The nature of the projects, duration of contact and the impact of the team projects are summarized in Table 2.

Participants were asked to evaluate their own projects in order to find out whether they perceived their contact as generally satisfactory or not. Most of the participants evaluated the intervention positively, that is 92.6% (n = 75) strongly agreed that the intervention increased their understanding and knowledge of HIV stigma and discrimination and 77.7% (n = 63) strongly agreed that their group's intervention aimed at increasing an understanding of HIV stigma.

Opinion leaders from all five sites felt that the intervention heightened the awareness of HIV-related stigma, that the intervention projects improved the morale of the community and health care workers in the health setting because there was greater understanding among nurses and PLHA.

Discussion

The intervention involved three components (information, contact, and empowerment). The five sites all implemented the same workshop program. They supplied the same information and therefore the information component was successfully implemented. The contact between nurses and PLHA was between 35 and 49 hours in duration, with an average of 40 hours. This was more time than was reported in other intervention studies. For instance, Chesney et al.21 did coping training for about 10 hours, Gordon-Garofalo17 did psycho-educational group interventions for about 12 hours, and Pomeroy et al. (1995) did psycho-educational and task-centered groups for approximately 12 hours. The only study we found that focused on health workers and included contact25 used 3-day workshops, but the PLHA were not present the whole time. All five teams planned and implemented an intervention that could be described as empowering. The intervention was successfully implemented, without significant problems, which allows for the evaluation of the intervention.

The positive evaluation of the intervention by the teams and opinion leaders in all sites may be attributed to the Hawthorne effect, but the fact that the teams in most sites took their interventions to other sites leads one to believe that the response was genuinely positive. The measured changes in health behavior or both nurses and PLHA team members support such an interpretation.

The results for the PLHA who participated show that they experienced a significant decrease in total stigma score, particularly in the subscales Workplace Stigma and Negative Self-Perception, as well as a significant increase in self-esteem. This is an important result, and may be related to the involvement of the nurses. Waterman et al.,12 who investigated stigma in Kenya, found that “power brokerage,” or the power to persuade the community, was an important factor in mobilizing support for HIV and AIDS strategies. They ascribe such power to those in senior positions, health professionals, and leaders. Our intervention has much in common with the Stigma Elimination Programme (STEP) used in Nepal with leprosy.13 The STEP intervention is also focused on empowerment and assisting persons affected by leprosy to become change agents in the area of economic development in their own communities. Although they used a social participation index as a measure, and not a direct stigma measure, their study indicated positive results.

Among nurses who participated, the most impressive result was the significant increase in voluntary testing (from 79.1% to 93% in the team and from 86.6% to 93.3% in the setting nurses). These are very high percentages compared to other studies in Africa. Hutchinson et al.26 reported a 13% level in a sample of 417 members of the general public in rural South Africa, while Kalichman and Simbayi27 reported a history of knowing their own status of 27% in 429 urban dwellers in the same country. It is encouraging that these nurses, who carry a double risk for HIV due to occupational exposure, are taking steps to know their own status. The increased testing behavior as a result of the intervention can be seen as an indicator of empowerment, because the stigma score as perceived by the same group did not show a significant decrease.

FIG. 1.

Total stigma scores by time as experienced by people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHA; n = 41) in five countries.

The study had some limitations. The first is that five unique case studies were combined, which might have masked differences among the settings. The small samples, especially of intervention team members, further limit the generalizability of the results. The sustainability over time was not tested, since all posttests were done within a month of the intervention. All the interventions were in hospitals and primary health care settings were not included. This might be realistic in that much of the delivery of ARVs are through hospital settings, but the primary health care services are closer to the communities and including such services would be important for greater coverage. Both the nurses and the PLHA team members were conveniently chosen. They might therefore have had a prior interest in the topic, predisposing them to involvement and this might lead to a more positive response to the intervention than would otherwise be possible. The teams were not exactly the same size in all cases. However, such variations are acceptable in a case study design. Despite these limitations, the study shows that stigma interventions of this kind can be effective in reducing stigma among PLHA and deserves further testing.

Conclusion

The intervention as implemented in all five countries was inclusive, action-oriented, and well received. It led to understanding and mutual support between nurses and PLHA and created some momentum in all the settings for continued activity. PLHA involved in the intervention teams reported less stigma and increased self-esteem. Nurses in the intervention teams and the settings reported no reduction in stigma or increases in self-esteem and self-efficacy, but their HIV testing behavior increased significantly.

The results of this study lead directly to the identification of further research needs. In the first instance, proper intervention studies need to be undertaken in which control groups and randomization will make it possible to ascribe change to the intervention. But at the same time it is important that the social dimensions of the stigma experience, and its interactions with other social processes such as stigma consciousness, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and coping should be explored. Another important line in research is the measurement of the results of stigma. The impact this intervention seems to have on HIV testing among the nurses raises the question of quantifying the impact of stigma on voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) uptake, ARV uptake, and disclosure. These are three of the most important health behaviors linked with high stigma levels, but few studies empirically link these. Last, the question is whether the intervention is successful only with those involved in the intervention team, or whether it can also influence the level of stigma in the institution and even in the community.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Grant #R01 TW06395 funded by the Fogarty International Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Kohi TW. Makoae L. Chirwa M, et al. HIV and AIDS stigma violates human rights in five African countries. Nurs Ethics. 2006;13:404–415. doi: 10.1191/0969733006ne865oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naidoo JR. Uys LR. Greeff M, et al. Urban and rural differences in HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. Afri J AIDS Res. 2007;6:17–23. doi: 10.2989/16085900709490395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uys L. Chirwa M. Dlamini P, et al. Eating plastic, winning the lotto, joining the WWW: Descriptions of HIV/AIDS in Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2005;16:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holzemer WL. Uys LR. Chirwa ML, et al. Validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument—PLWA (HASI-P) AIDS Care. 2007;19:1002–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120701245999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dlamini P. Kohi T. Uys L, et al. Manifestations of HIV/AIDS stigma: Verbal and physical and neglect abuse in five African countries. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24:389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greeff M. Phetlhu DR. Makoae LN, et al. Disclosure of HIV status: Experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in five Africa countries. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:311–324. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makoae L. Greeff M. Phethlu R, et al. Coping strategies for HIV and AIDS: A multinational African Study. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uys LR. Holzemer WL. Chirwa ML, et al. The development and validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument-Nurse (HASI-N) AIDS Care. 2009;21:150–159. doi: 10.1080/09540120801982889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holzemer WL. Makoae L. Greeff M, et al. Measuring HIV stigma for PLHAs and nurses over time in five African countries. SAHARA J. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2009.9724933. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dlamini PS. Wantland D. Makoae L, et al. The impact of perceived HIV stigma on reasons for missing ARV medication among persons living with HIV infection in five Africa countries. PLOS Med. (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown L. Macintyre K. Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waterman H. Power brokering, empowering, and educating: The role of home-based care professionals in the reduction of HIV-related stigma in Kenya. Qual Health Res. 2007;17:1028–1039. doi: 10.1177/1049732307307524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cross H. Choudhary R. STEP: An intervention to address the issue of stigma related to leprosy in Southern Nepal. Lepr Rev. 2005;76:316–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fife BL. Wright ER. The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41:50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Able E. Rew L. Gortner EM. Delville CL. Cognitive reorganization and stigmatization among persons with HIV. J Adv Nurs. 2004;2004;47:510–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li L. Lin C. Wu Z, et al. Stigmatization and Shame: Consequences of caring for HIV/AIDS Patients in China. AIDS Care. 2007;19:258–263. doi: 10.1080/09540120600828473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon-Garofalo VL. Rubin A. HIV/AIDS evaluation of a psychoeducational group for seronegative partners and spouses of persons with HIV/AIDS. Res Soc Work Pract. 2004;14:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holzemer WL. Uys L. Makoae L, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58:541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahendra VS. Gilborn L. Bharat S. Understanding, measuring AIDS-related stigma in health care Settings: A developing country perspective. J Soc Aspects HIV/AIDS. 2007;4:616–625. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chesney MA. Chambers D. Taylor TM. Johnson LM. Folkman S. Coping effectiveness training for men living with HIV: Results from a randomized clinical trial testing a group-based intervention. Psychosom Med. 2003;2003;65:1038–1046. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000097344.78697.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puhl R. Brownell KD. Ways of coping with obesity stigma: Review and conceptual analysis. Eating Behav. 2003;4:53–78. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(02)00096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jerusalem M. Schwarzer R. The generalised self efficacy scale. 1992. http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/engscal.htm. [Sep 22;2009 ]. http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/engscal.htm

- 24.Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale (SES) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lueveswanij S. Nittayananta W. Robison VA. Changing knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Thai oral health personnel with regard to AIDS: An evaluation of an educational intervention. Community Dent Health. 2000;17:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutchinson PL. Mahlalela X. Yukich J. Mass media, stigma, and disclosure of HIV test results: Multilevel analysis in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2007;19:489–510. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2007.19.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalichman SC. Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]