Abstract

The ability of class I alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1) and class IV alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH4) to metabolize retinol to retinoic acid is supported by genetic studies in mice carrying Adh1 or Adh4 gene disruptions. To differentiate the physiological roles of ADH1 and ADH4 in retinoid metabolism we report here the generation of an Adh1/4 double null mutant mouse and its comparison to single null mutants. We demonstrate that loss of both ADH1 and ADH4 does not have additive effects, either for production of retinoic acid needed for development or for retinol turnover to minimize toxicity. During gestational vitamin A deficiency Adh4 and Adh1/4 mutants exhibit completely penetrant postnatal lethality by day 15 and day 24, respectively, while 60% of Adh1 mutants survive to adulthood similar to wild-type. Following administration of a 50-mg/kg dose of retinol to examine retinol turnover, Adh1 and Adh1/4 mutants exhibit similar 10-fold decreases in retinoic acid production, whereas Adh4 mutants have only a slight decrease. LD50 studies indicate a large increase in acute retinol toxicity for Adh1 mutants, a small increase for Adh4 mutants, and an intermediate increase for Adh1/4 mutants. Chronic retinol supplementation during gestation resulted in 65% postnatal lethality in Adh1 mutants, whereas only ~5% for Adh1/4 and Adh4 mutants. These studies indicate that ADH1 provides considerable protection against vitamin A toxicity, whereas ADH4 promotes survival during vitamin A deficiency, thus demonstrating largely non-overlapping functions for these enzymes in retinoid metabolism.

One aspect of retinoid signaling that is not yet well understood is the nature of the enzymes that metabolize vitamin A (retinol) to retinoic acid (RA)1 either for retinoid turnover or for production of the active form needed for growth and development. Such metabolism is dependent upon enzymes capable of catalyzing a two-step conversion of retinol to RA with retinal as the intermediate (1). RA produced in this fashion either functions as a ligand for RA receptors known to control vertebrate development (2), or it is further metabolized to more polar derivatives to facilitate excretion (3).

Studies on the second step of RA synthesis, oxidation of retinal to RA, have yielded consistent results indicating that three forms of cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase referred to as retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) participate in RA synthesis (1). In vitro activities are reported for RALDH1 (4), RALDH2 (5–7), and RALDH3 (8), plus in vivo activities are reported for RALDH1 and RALDH2 (9, 10). Gene disruption studies demonstrate that RALDH2 is essential for catalyzing the second step of RA synthesis during development as Raldh2−/− embryos die at mid-gestation and almost totally lack RA (11, 12). Raldh2−/− embryonic development can be partially rescued with limited maternal RA treatment, and rescued embryos express RALDH1 and RALDH3 as well as at least one additional RA-generating enzyme, all of which may contribute to the rescue (12).

Several enzymes capable of catalyzing the first step of RA synthesis, oxidation of retinol to retinal, have been identified within the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) families (1), plus there exists a recently identified cytosolic form that is a member of the aldoketo reductase family (13). The human and mouse ADH families each contain five classes of cytosolic enzymes (14) encoded by a tight cluster of genes tandemly organized in the same transcriptional orientation on chromosome 4 (human) or chromosome 3 (mouse) (15). ADHs of class I (ADH1), class II (ADH2), and class IV (ADH4) have long been known to catalyze the oxidation of retinol to retinal in vitro (16–19), and recently class III (ADH3) has been added to this list (20). The SDR family (21) includes the microsomal enzymes RoDH (22), CRAD (23), and RDH5 (24) that can also oxidize retinol to retinal in vitro. RDH5 functions in vivo as an 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenase to generate the visual pigment 11-cis-retinal (25, 26). Thus, microsomal oxidation of retinol to retinal by SDRs may have functions distinct from RA synthesis such as the one revealed for vision, whereas cytosolic oxidation of retinol to retinal by ADH or aldo-keto reductase may contribute to RA synthesis by cytosolic RALDHs.

Gene disruption studies have also provided evidence of a physiological function for ADH in RA production. Adh4−/− mice are viable but suffer increased postnatal lethality during gestational vitamin A deficiency (VAD) compared with wild-type mice (27). Thus, ADH4 can be considered essential for RA production to ensure postnatal survival during VAD, a condition commonly encountered by animals in natural environments. Studies on Adh3−/− mice have shown that ADH3 also minimizes the effect of gestational VAD but is also needed to maintain growth on a standard diet (20). In addition, Adh1−/− mice are viable and behave no worse than wild-type mice during gestational VAD (20) but suffer a large reduction in metabolism of a dose of retinol to RA (28). Thus, whereas ADH3-and ADH4-catalyzed RA production is necessary for supplying the ligand for nuclear receptors to fulfill the function of vitamin A in development, it is possible that ADH1-catalyzed RA synthesis functions in another fashion, perhaps the oxidative elimination of excess retinol to prevent vitamin A toxicity. That excess vitamin A is toxic has been well established (29–31) and has resulted in the recommendation that consumption of vitamin A-rich foods or vitamin A supplements be limited, particularly during pregnancy as fetal development is most sensitive (32). The main oxidative pathway for retinol turnover is the oxidation of retinol to retinal and then oxidation of retinal to RA followed by glucuronide conjugation of the acid and/or 4-hydroxylation of RA (3). The enzyme responsible for oxidizing excess retinol to retinal to initiate this catabolic pathway has not been identified.

To examine the physiological roles of ADH1 and ADH4 in retinoid metabolism we report here the generation of an Adh1/4 double null mutant mouse line and its comparison to single null mutants when challenged by vitamin A deficiency or toxicity. These genetic findings demonstrate that ADH1 and ADH4 have evolved to perform largely non-overlapping roles in retinoid metabolism, ADH1 in minimizing vitamin A toxicity and ADH4 in survival during VAD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Construction of Adh1-hygro Gene Targeting Vector

A gene replacement targeting vector for Adh1 carrying a hygromycin-positive selection marker (PGK-hygro) was produced by alteration of an Adh1 targeting vector containing a neomycin-positive selection marker (PGK-neo) as well as a thymidine kinase-negative selection marker (PGK-TK) as previously described (28). A portion of the neomycin resistance gene was removed from this vector with BamHI and XhoI and replaced with a 2.2-kb BamHI-XhoI fragment containing the hygromycin resistance gene controlled by the PGK promoter (33). In this vector, exons 7–9 plus the polyadenylation signal of Adh1 are replaced by PGK-hygro.

Generation of Adh1/4 Double Null Mutant Mice

The Adh1-hygro gene targeting vector described above was linearized with NotI and introduced by electroporation using standard methodology (34) into Adh4+/− mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells that were previously targeted for Adh4 with a neomycin resistance marker (27). To enrich for Adh4+/− ES cells incorporating the Adh1-hygro construct by homologous recombination, positive selection was with 125 µg/ml hygromycin B and negative selection was with 2 µm gancyclovir. Identification of Adh4+/− ES cells carrying also a deletion in Adh1 was accomplished by Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA isolated from ~200 surviving cell clones (35). Genomic DNA was digested with HindIII, and an external DNA probe for Southern blot analysis consisted of a 0.2-kb EcoRV-HindIII fragment from the 3′-flanking region of Adh1 (36). The wild-type and mutant Adh1 alleles were identified by 2.8- and 5.7-kb HindIII fragments, respectively. As it was desired to obtain an ES cell clone in which the Adh1 targeting event had occurred on the same copy of chromosome 3 already targeted for Adh4 as opposed to the wild-type chromosome 3, several independently isolated double-targeted clones were isolated.

Several Adh1+/−Adh4+/− double heterozygous ES cell clones were subjected to karyotype analysis to identify those having a normal karyotype for blastocyst injection. Adh1+/−Adh4+/− ES cell clones (clones 9 and 64) were microinjected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts, which were then implanted into pseudopregnant females resulting in chimeric mice identified by partial agouti coat color (34). Male chimeric mice derived from each ES cell line were mated to wild-type female Black Swiss mice, and germ line transmission was identified by agouti coat color. Agouti offspring were subjected to Southern blot analysis of tail DNA (35) to identify Adh1+/−Adh4+/− individuals heterozygous for mutations in both Adh1 and Adh4 using the probe described above for Adh1 as well as an Adh4 probe described previously in which the wild-type and mutant Adh4 alleles are identified by 4.0-kb and 5.8-kb HindIII fragments, respectively (27). Mice derived from ES cell clone 9 were found to possess mutations in both Adh1 and Adh4 and hence carry a copy of chromosome 3 in which both genes are mutated. Heterozygous Adh1+/− Adh4+/− matings were performed to produce homozygous Adh1−/− Adh4−/− mice and wild-type mice identified by Southern blot analysis of tail DNA. Adh1−/−Adh4−/− mice (referred to as Adh1/4 null mutant mice or Adh1/4−/− mice) and wild-type mice were then expanded to form permanent mouse lines maintained under standard laboratory conditions. Other mice used in this study are the original Adh1−/− and Adh4−/− null mutant lines previously described (27, 28) both of which have the same genetic background as the Adh1/4 and wild-type mice described here. For verification of a null mutant phenotype, polyclonal antibodies against mouse ADH1 and ADH4 were used to probe Western blots of mouse liver and stomach using 20 µg of total protein per lane as reported (37).

Generation of VAD Mice

Gestational VAD was induced by a modification of previous methods (27). For each mouse strain, original parental mice (three mating pairs each) were placed on Purina VAD diet 5822 (vitamin A <0.22 IU/g) at the beginning of mating, and resulting offspring were maintained on this diet. Congenitally VAD F1 generation females were mated at 6-weeks-old (to males maintained on standard mouse chow to remain fertile), thus producing congenitally VAD F2 generation offspring. For both rounds of matings, females were separated from males before birth to ensure that they did not again become pregnant during postnatal development of their offspring. Blood was collected and serum all-trans-retinol was quantitated by HPLC analysis as indicated below.

Acute Retinol Treatment

For analysis of retinoic acid production following a single acute retinol dose, retinol was administered essentially as described (38). All-trans-retinol (Sigma) was dissolved in acetone-Tween 20-water (0.25:5:4.75 v/v/v) and was administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg by oral injection to female mice (age- and weight-matched). After 2 h, liver and blood were collected and stored at −20 °C until HPLC analysis as described below.

For determination of the retinol lethal dose, mice were given a single oral dose of retinol as previously reported (29). Male 14-week-old mice were used for all strains examined. All-trans-retinol (Sigma) was dissolved in corn oil and administered by oral intubation at 0.2 ml/10 g of body weight. Doses ranged from 0.5 to 3.5 g/kg. Lethality was monitored daily during 14 days after retinol administration. A dose resulting in the death of 50% of the mice (LD50) by day 14, plus the 95% confidence limits for the LD50 dose, were calculated using the methods of Litchfield and Wilcoxon (39).

HPLC Measurement of Retinol and Retinoic Acid

Liver (250 mg) was homogenized on ice in 2 ml of methanol-acetone (50:50 v/v), whereas serum (200 µl) was extracted with 2 ml of methanol-acetone (50:50 v/v). After centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the organic phase was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in 200 µl of methanol-dimethyl sulfoxide (50:50 v/v). Samples were analyzed by HPLC to quantitate retinoid levels using standards for all-trans-RA and all-trans-retinol (Sigma). Reversed-phase HPLC analysis was performed using a Microsorb-MVTM 100 C18 column (4.5 × 250 mm) (Varian) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Mobile phase consisted of 0.5 m ammonium acetate-methanol-acetonitrile (25:65:10 v/v) (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B). The A:B (v/v) gradient composition was 100:0 at the time of injection, 70:30 at 1 min, 65:35 at 14 min, and 0:100 at 16 min. UV detection was carried out at 340 nm.

Dietary Vitamin A Supplementation

Statistical significance was determined for raw data with Statistica version 5.0 software using the unpaired Student’s t test (two-tailed). Mice were propagated on either Purina 5015 standard mouse chow, which contains the standard amount of vitamin A (30 IU/g) or Purina 5755 basal diet supplemented with additional retinyl acetate to bring the total vitamin A concentration to 300 IU/g all in the form of retinyl acetate, which is quickly hydrolyzed to retinol in the digestive tract. Two groups of adult female mice, which had been placed on one or the other of these diets for 2 weeks, were mated with males while being maintained on their respective diets to generate offspring, which were also maintained, respectively, on the same diet after weaning.

RESULTS

Generation of Adh1/4 Double Null Mutant Mice

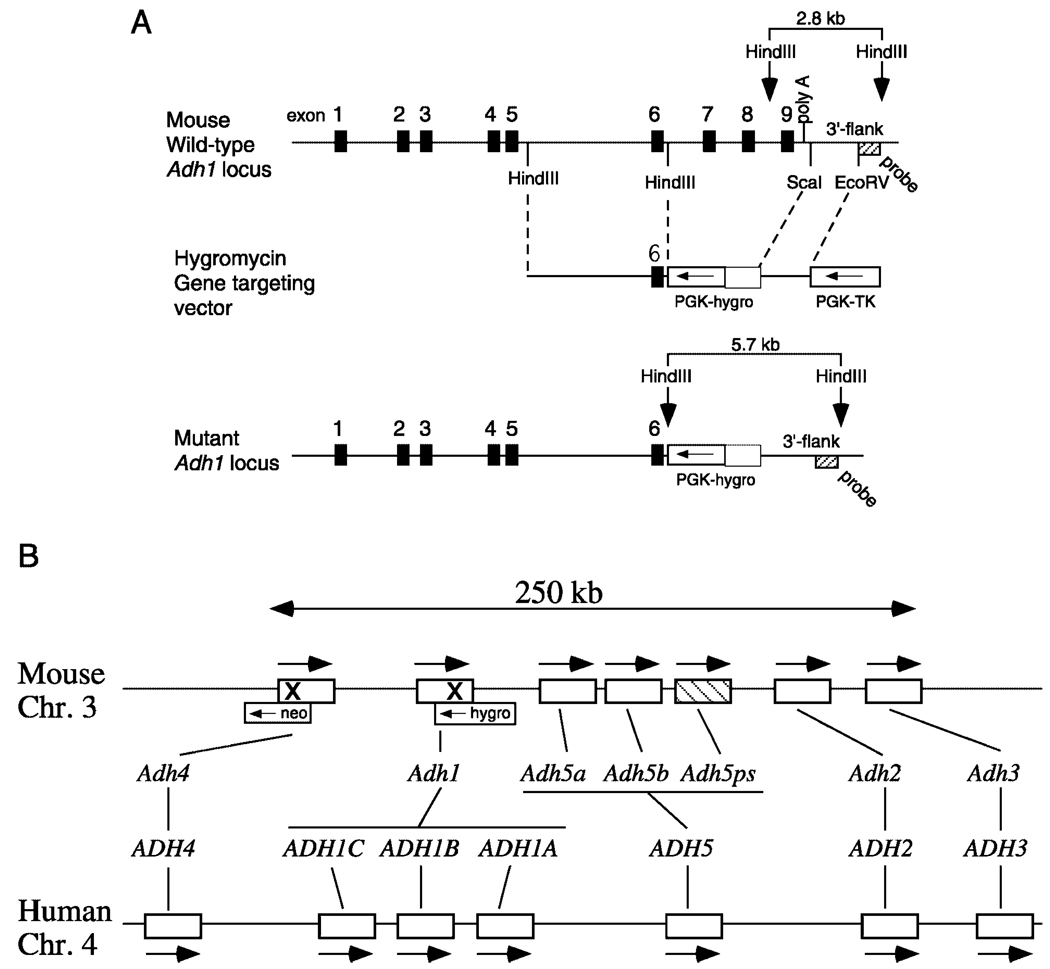

Mice carrying single null mutants for either Adh1 or Adh4 have been previously described (27, 28). Analysis of the mouse Adh gene complex (15) has shown that Adh1 and Adh4 are closely linked on mouse chromosome 3 along with four other functional Adh genes and a pseudogene (Fig. 1B). Thus, a double null mutant would not be able to be obtained by simple matings of the two single mutants unless a rare crossing-over event occurred between the two mutant genes on homologous chromosomes to produce a single copy of chromosome 3 carrying both mutations. Instead, double null mutants were obtained by sequential gene targeting of ES cells starting with Adh4+/− ES cells, i.e. the cell line used to generate Adh4−/− mice targeted with an Adh4-neo vector providing G418 selection (27). As Adh4+/− ES cells already possess G418 resistance, they were electroporated with an Adh1-hygro gene targeting vector that carries the hygromycin selectable marker (Fig. 1A). Incorporation of this vector deletes exons 7–9 plus the polyadenylation site, thus producing the same type of mutation previously reported for Adh1−/− mice that were targeted with an Adh1-neo vector (28). As this gene targeting event could occur either on the copy of chromosome 3 containing the null mutant allele of Adh4 (which was desired) or on the other copy containing the wild-type allele of Adh4 (not desired), this was sorted out when targeted ES cells were introduced into mice and screened by Southern blot analysis for mutations in both Adh1 and Adh4 as described under “Experimental Procedures.” One ES cell line (clone 9) produced the desired result, thus generating Adh1+/− Adh4+/− (Adh1/4+/−) double heterozygous mice in which the two mutant alleles segregated essentially as a single trait.

FIG. 1. Targeting of both Adh1 and Adh4 on the same chromosome.

A, shown are the wild-type Adh1 gene containing nine exons, the Adh1-hygro gene replacement targeting vector, and the mutant Adh1 locus in which exons 7–9 and the polyadenylation signal have been deleted (replaced by the hygromycin resistance gene PGK-hygro). B, a comparison of the ADH gene complexes for mouse (chromosome 3) and human (chromosome 4) shows that each species contains five classes of ADH genes (numbered 1–5) arranged in the same order with arrows indicating that all genes are in the same transcriptional orientation; mouse and human differ in that mouse contains three class V genes (one being a pseudogene indicated by cross-hatching), whereas human contains three class I genes (15). For mouse, it can be seen that Adh4 and Adh1 (shown here with an X indicating the site of targeting with neomycin (neo) or hygromycin (hygro)) are located close together at the upstream end of the complex.

Mating of Adh1/4+/− mice resulted in the production of Adh1/4−/− double homozygous mice that were viable and that were generated at the normal Mendelian ratio (10 litters from double heterozygous parents resulted in −/−, 26%, n = 21; −/+, 46%, n = 36; +/+, 28%, n = 22). This is similar to the results reported for each single mutant (27, 28). Also, Adh1/4−/− mice were fertile and a homozygous line was established. Western blot analysis verified that Adh1/4−/− mice lacked both ADH1 and ADH4 proteins (data not shown).

Survival and Growth of Adh Null Mutant Mice

To determine whether the loss of ADH1 or ADH4 or both enzymes negatively impacts viability and growth when maintained under normal laboratory conditions, we examined the generation, survival, and growth of each of the mouse strains on standard mouse chow. Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, and Adh1/4−/− mice showed no significant difference with wild-type (WT) with respect to reproductive ability, survival, or body weight at maturity (Table I). As Adh1/4−/− mice were able to reproduce and develop similar to Adh1−/− and Adh4−/− single mutants, this indicates that a third retinol-metabolizing enzyme must exist for production of RA needed during development.

TABLE I. Survival and growth of mice lacking ADH1 or ADH4 or both.

% survival refers to mice alive at weaning. For determination of body weight at 14-weeks-old: M (male), n = 14; F (female), n = 7; values are mean ± S.E.

| Genotype | Litters | Pups born | Pups/litter | Postnatal mortality |

% Survival/ no. |

Weight at 14 weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g | ||||||

| Wild-type | 17 | 144 | 8.47 ± 0.47 | 1 | 99.3 (143) | M 34.3 ± 1.2 F 26.3 ± 0.7 |

| Adh1 −/− | 17 | 151 | 8.88 ± 0.49 | 7 | 95.4 (144) | M 34.4 ± 3.2 F 27.8 ± 1.1 |

| Adh4 −/− | 17 | 166 | 9.76 ± 0.63 | 3 | 98.2 (163) | M 38.2 ± 3.4 F 26.2 ± 1.1 |

| Adh1/4 −/− | 17 | 141 | 8.31 ± 0.50 | 6 | 95.7 (136) | M 35.1 ± 2.6 F 27.3 ± 2.2 |

Effect of VAD on Adh Null Mutant Mice

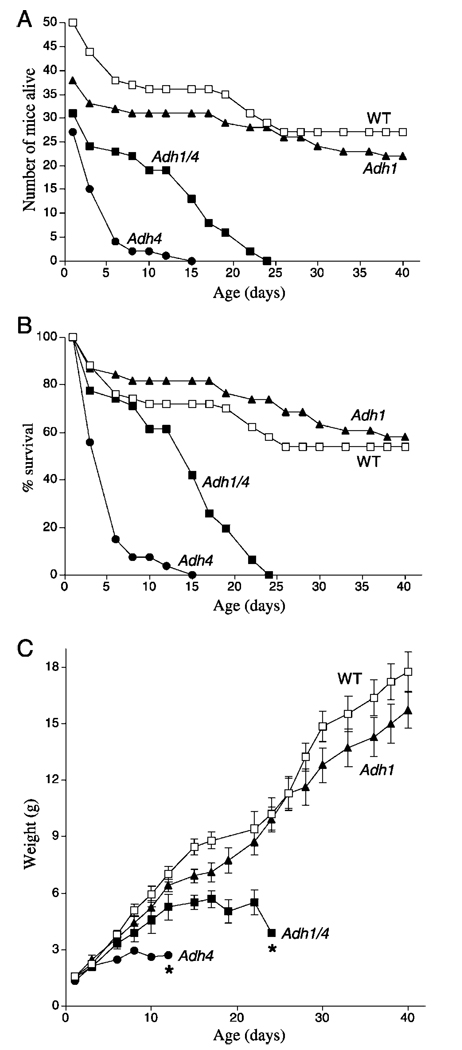

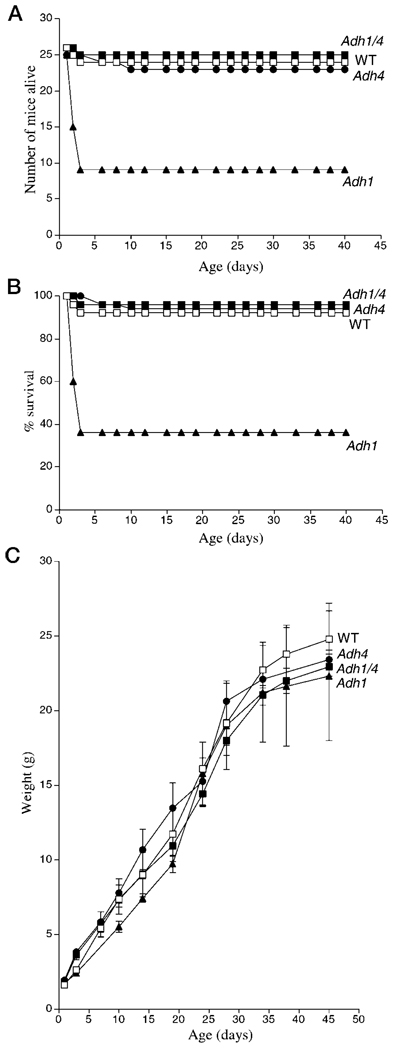

We previously reported that Adh4−/− mice exposed to gestational VAD suffer increased postnatal lethality compared with WT mice (27). Here we compared Adh4−/− and WT mice with Adh1−/− and Adh1/4−/− mice for survival and growth during gestational VAD. Mice were mated for two generations on a VAD diet in order to induce severe deficiency in the F2 generation during development. As expected from previous studies (27), Adh4−/− F2 generation mice were severely effected by VAD, displaying 100% lethality by postnatal day 15 (P15) (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast, WT and Adh1−/− mice both exhibited ~60% survival at P40. Adh1/4−/− mice did not perform worse than Adh4−/− mice, but instead survived a little longer, with 100% lethality by P24 (Fig. 2, A and B)

FIG. 2. Effect of Adh gene targeting on postnatal lethality during gestational VAD.

A, shown are the number of congenitally VAD F2 generation offspring born for Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, Adh1/4−/−, and WT mice, and the number of individuals that survived until P40. 100% postnatal lethality is indicated for Adh4−/− and Adh1/4−/− mice by P15 and P24, respectively. B, the data in the previous panel are shown plotted as the % survival for each mouse strain. C, shown are the weight gains from birth to P40 for the VAD mice in the previous panels. *, 100% postnatal mortality occurred by the day indicated. Data for some of the mice used here (WT, Adh1−/−, and Adh4−/−) are also described previously (20).

Adh4−/− and Adh1/4−/− VAD mice exhibited severe growth deficiency in the F2 generation compared with WT and Adh1−/− mice. Whereas WT and Adh1−/− mice had comparable body weights from birth to P40 and achieved weights of 16–18 g, growth of Adh4−/− mice began to deviate downward from WT at P4, and body weights beyond 3 g were not achieved before death; growth of Adh1/4−/− mice began to deviate downward from WT at P8, and body weights beyond 6 g were not achieved before death (Fig. 2C)

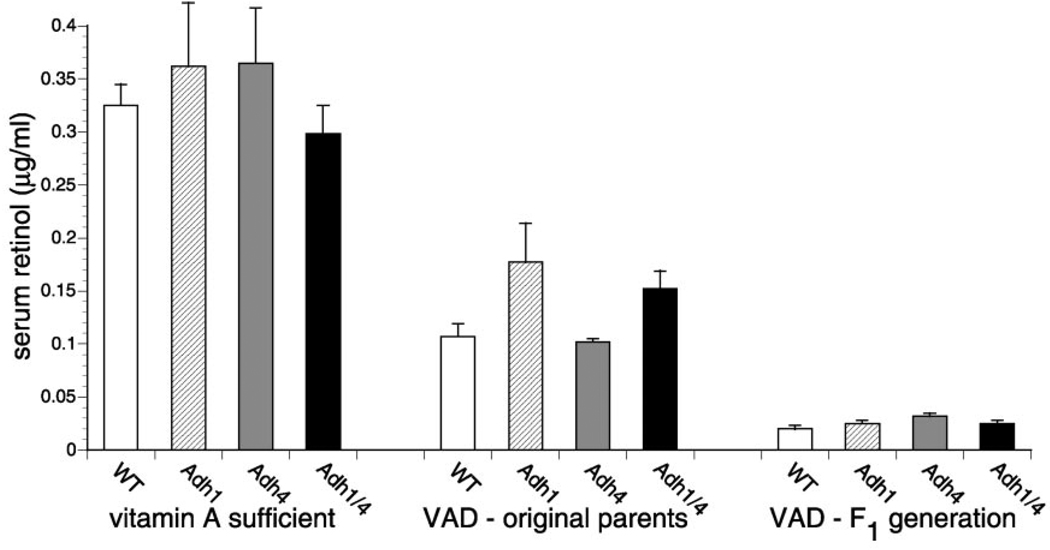

Measurement of serum retinol in the female mice used to generate the VAD F2 generation offspring verified that each mouse strain had become essentially equally deficient (Fig. 3). Values for serum all-trans-retinol in control females maintained on standard mouse chow ranged from 0.3–0.4 µg/ml among the strains, and this fell to 0.1–0.17 µg/ml for the original female parents maintained on the VAD diet for 8 weeks and fell further to ~0.03 µg/ml for each strain of congenitally VAD F1 generation females that served as parents for the F2 generation described above. Thus, the completely penetrant postnatal lethality observed in Adh4−/− and Adh1/4−/− mice subjected to VAD was not due to significant differences in the level of serum all-trans-retinol in these strains relative to WT and Adh1−/− mice.

FIG. 3. Depletion of serum retinol during gestational VAD.

HPLC quantitation of serum all-trans-retinol during VAD was performed for WT, Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, and Adh1/4−/− female mice matched for age. On the left, control values are shown for 14-week-old vitamin A-sufficient female mice (n = 3) for each strain maintained on standard mouse chow. In the middle, values for VAD (original parents) refer to the original female parents used to begin the VAD studies (n = 3), which were placed on the VAD diet at 6-weeks-old, mated to produce one litter, and then examined for serum retinol at 14-weeks-old. On the right, values for VAD (F1 generation) refer to the female offspring (n = 8) of the original VAD female parents; these congenitally VAD offspring underwent a single mating at 6-weeks-old to produce the F2 generation mice described in Fig. 2, and then serum retinol was measured at 14-weeks-old. Serum retinol data are also presented elsewhere for some of the strains (WT, Adh1−/−, and Adh4−/−) (20).

As Adh1−/− mice and WT had similar survival and growth during VAD, there is no evidence that ADH1 provides protection against VAD. Also, there is no additive effect on VAD when both ADH1 and ADH4 are missing. Instead, these experiments show that when mice lacking both ADH1 and ADH4 are exposed to VAD, they will survive longer and experience more growth than mice lacking only ADH4. This interesting relationship between ADH1 and ADH4 is discussed further below.

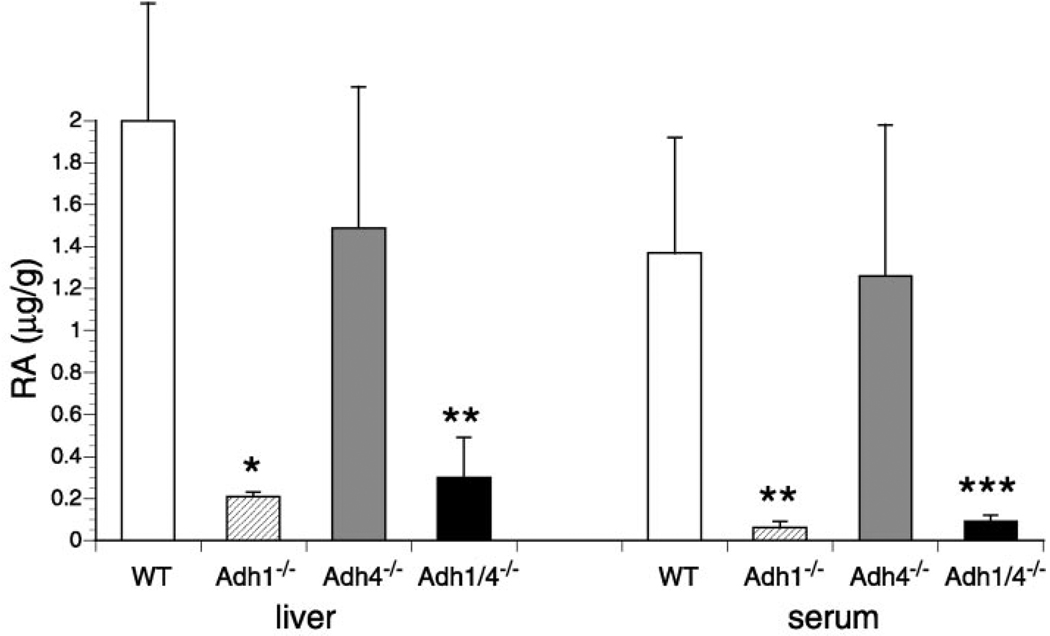

Effect of Adh Genotype on Metabolism of Retinol to Retinoic Acid

To examine oxidative turnover of retinol, mice were treated orally with a 50-mg/kg dose of all-trans-retinol, and 2 h later all-trans-RA was quantitated in liver and serum. WT mice generated high levels of all-trans-RA in response to this dose of retinol (2.0 ± 0.6 µg/ml in liver and 1.4 ± 0.5 µg/ml in serum). We observed that Adh1−/− mice had a 10-fold reduction of all-trans-RA in liver (0.2 ± 0.02 µg/ml) and a 23-fold reduction in serum (0.06 ± 0.03 µg/ml) relative to WT (Fig. 4). Adh1/4−/− mice behaved similarly to Adh1−/− mice, whereas Adh4−/− mice had small decreases of all-trans-RA in liver (1.5 ± 0.7 µg/ml) and serum (1.3 ± 0.7 µg/ml) that were not statistically different from WT (Fig. 4). These findings demonstrate a very large role for ADH1 in oxidative clearance of retinol. ADH4 was found to contribute very little to this metabolism, and Adh1/4−/− mice did not exhibit a further reduction in RA production relative to Adh1−/− mice.

FIG. 4. Contribution of ADH1 and/or ADH4 to metabolism of retinol to RA.

All-trans-RA levels were quantitated by HPLC in liver (µg/g) and serum (µg/ml) of WT, Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, and Adh1/4−/− female mice 2 h after a 50-mg/kg oral dose of all-trans-retinol. All values are from adult female mice (n = 4). Serum RA data for WT, Adh1−/−, and Adh4−/− are also reported previously (20). All values are means ± S.E. *, p < 0.01; **, p < 0.03; *** p < 0.05 (significantly different from the WT value; unpaired Student’s t test).

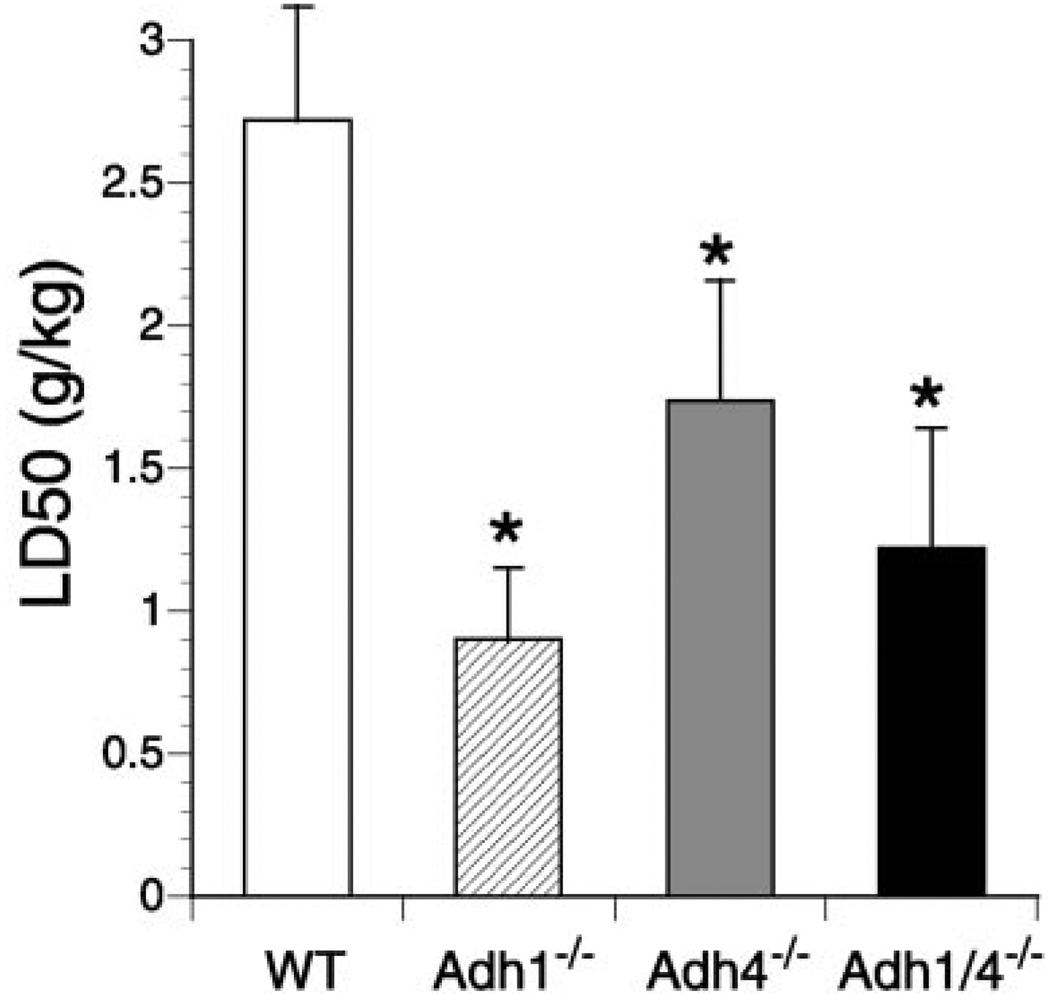

Determination of Retinol LD50 Values to Examine Acute Retinol Toxicity

We examined the effect of Adh genotype on acute retinol toxicity by determining the LD50 values for each null mutant strain compared with WT. In our hands, WT mice exhibited a retinol LD50 value of 2.72 g/kg, very close to the value of 2.52 g/kg previously reported for mice (29). Retinol toxicity was greatly increased in Adh1−/− mice, which exhibited a much smaller LD50 of 0.9 g/kg (3-fold less than WT), whereas there was a much smaller increase in toxicity in Adh4−/− mice (LD50 = 1.74 g/kg, 1.6-fold less than WT) but an intermediate level of toxicity in Adh1/4−/− mice (LD50 = 1.22 g/kg, 2.2-fold less than WT) (Fig. 5). These findings indicate that ADH1 plays a major role in providing protection against retinol toxicity, whereas ADH4 plays a relatively minor role. Importantly, the loss of both does not lead to a further increase in toxicity. Instead, the Adh1/4−/− results show that the greatly increased retinol toxicity observed when ADH1 is missing is moderated when ADH4 is also missing, further pointing out an interesting relationship between ADH1 and ADH4.

FIG. 5. Retinol toxicity assessed by retinol LD50 determination.

Retinol LD50 values are compared for WT, Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, and Adh1/4−/− mice. All values are means ± S.E. *, p < 0.05 (significantly different from the WT value; Litchfield and Wilcoxon test).

Chronic Retinol Toxicity via Dietary Retinol Supplementation

To examine the effect of chronic retinol treatment on development, mice were propagated for one generation on a retinol-supplemented diet (300 IU/g) containing 10-fold higher vitamin A than normal mouse chow (30 IU/g). Adh1−/− mice exhibited a high incidence of postnatal mortality from birth through day 3 resulting in only 36% survival to adulthood compared with Adh4−/− and WT mice, which each exhibited ~95% survival to adulthood (Fig. 6, A and B). Interestingly, the retinol-supplemented diet did not have a noticeable effect on survival of Adh1/4−/− mice, which behaved similar to WT (Fig. 6, A and B). This moderate level of retinol supplementation did not have a noticeable teratogenic effect on any strains nor an effect on survival or growth of any mice that survived past postnatal day 3 including those Adh1−/− mice that survived past that point (Fig. 6C). Thus, excessive death of Adh1−/− mice shortly after birth is most likely associated with a perturbation in the immediate adjustments needed for life outside the womb such as respiration, feeding, or digestive tract function. As the results for Adh1/4−/− mice indicate, the additional loss of ADH4 eliminates this toxic event. This provides yet one more example of a situation where the negative effect resulting from loss of ADH1 is moderated by the additional loss of ADH4.

FIG. 6. Effect of Adh genotype on postnatal lethality during chronic retinol treatment.

A, shown are the number of offspring born for Adh1−/−, Adh4−/−, Adh1/4−/−, and WT mice generated on a retinol-supplemented diet (300 IU/g vitamin A) and the number of individuals that survived until P40. B, the data in the previous panel are shown plotted as the % survival for each mouse strain. Adh1−/− mice experienced ~65% postnatal mortality between birth and P3, whereas the other strains had similar low levels of mortality (~5%). C, shown are the weight gains from birth to P45 for the retinol-treated mice in the previous panels.

DISCUSSION

The findings reported here indicate that ADH1 and ADH4 have mostly non-overlapping functions in retinol metabolism in vivo. This conclusion was achieved by comparison of Adh1/4−/− double null mutant mice with Adh1−/− and Adh4−/− single null mutant mice challenged with VAD or vitamin A toxicity. If ADH1 and ADH4 each provided protection against retinol deficiency and toxicity, we would have observed additive effects. However, this was not observed, and instead we revealed conditions in which the effect of a loss of one gene was moderated by the additional loss of the other gene.

ADH4, but not ADH1, provides protection against gestational VAD as 100% postnatal lethality is observed in Adh4−/− mice under VAD conditions where Adh1−/− and wild-type mice suffer only 40% postnatal lethality and show similar growth as described previously (20) and reported here for comparison with Adh1/4−/− mice. Our results here demonstrate that VAD Adh1/4−/− mice do not perform worse than VAD Adh4−/− mice during gestation, providing further evidence that ADH1 does not function to provide protection against VAD. Instead, Adh1/4−/− offspring display more growth and survive longer than Adh4−/− mice during VAD. As 100% postnatal lethality is still observed in both strains, the effect of ADH4 is dominant. However, the additional loss of ADH1 moderates the negative effect of a loss of ADH4 during gestational VAD perhaps by reducing retinol turnover.

Examination of oxidative retinol turnover provided clear evidence that ADH1 plays a major role in this metabolic pathway, with ADH4 playing a relatively minor role. Adh1−/− mice exhibit a 10-fold decrease in metabolism of retinol to RA in liver. This correlates with liver being the tissue where ADH1 protein is most highly expressed in the adult mouse (37). In contrast, Adh4−/− mice have a small decrease in conversion of retinol to RA in liver that is not statistically significant. In addition, Adh1/4−/− mice behave similar to Adh1−/− mice, indicating that there is not an additive effect when ADH1 and ADH4 retinol activities are both eliminated. As mammalian ADH1 and ADH4 each have high activity for oxidation of retinol to retinal (ADH1 activity reported as 30–300 nmol/min/mg; ADH4 activity reported as 110–1675 nmol/min/mg) (16–19), the lack of a major contribution by ADH4 in vivo is not due to lower retinol activity. However, it is consistent with the fact that ADH4 protein is not produced in mouse liver where a large amount of retinol metabolism is expected to occur (37). Adh1−/− and Adh1/4−/− mice, but not Adh4−/− mice, also exhibit large decreases in serum RA after retinol treatment, indicating that tissues expressing ADH1 are involved in most of the systemic turnover of retinol to RA, some of which escapes to the blood before further metabolism. ADH4 protein is found in the epithelia of several retinoid target tissues including the stomach, esophagus, skin, and respiratory tract (37, 40), but these tissues evidently do not account for much of the observed RA in the serum. This is likely due to the relatively small number of cells expressing ADH4 in those organs compared with the large number of cells in the liver expressing ADH1 at very high levels; in the mouse, 0.9% of liver protein is ADH1, whereas only 0.07% of stomach protein is ADH4 (41). Thus, the expression pattern of ADH4 precludes it from playing a major role in systemic retinol turnover but evidently allows it to function in metabolism of retinol to RA in peripheral tissues to provide protection against VAD.

Consistent with the retinol metabolic studies, we show that ADH1, but not ADH4, provides a great deal of protection against acute retinol toxicity in adult mice and chronic retinol toxicity during gestation. The LD50 values show that Adh1/4−/− mice do not have greater retinol toxicity than Adh1−/− mice, but rather an intermediate level of toxicity between that of Adh1−/− and Adh4−/− mice, indicating that there is not an additive effect on toxicity when both ADH1 and ADH4 are missing but instead a moderating effect. Thus, some of the observed toxicity in Adh1−/− mice may be due to excessive retinol utilization by ADH4 in peripheral tissues, and this is eliminated in Adh1/4−/− mice. Additional toxicity may result if retinol is not efficiently oxidized though an ADH1 pathway and is instead used as a substrate by P450s known to metabolize retinol to 4-hydroxyretinol (42). As P450-mediated metabolism requires molecular oxygen and produces oxygen-free radicals that can cause liver damage (43, 44), this may contribute to the increased incidence of death observed in our LD50 studies of Adh1−/− mice. We conclude that ADH1 minimizes toxicity by metabolizing retinol quickly to RA in the liver, thus diminishing retinol utilization both by ADH4 in peripheral tissues as well as by P450s in liver or elsewhere.

The observation that ADH1 and ADH4 do not have additive effects on retinoid metabolism during VAD or vitamin A toxicity can also be coupled with the observation that they do not have additive effects during development, i.e. Adh1/4−/− mice lacking both of these enzymes are viable and can reproduce when maintained under normal laboratory conditions on a standard diet. Thus, although ADH4 facilitates development during VAD, there exists at least one additional retinol-oxidizing enzyme that functions physiologically to produce retinal for RA production throughout development. The most obvious candidate is ubiquitously expressed ADH3 for which there now exists genetic evidence of a physiological function in RA synthesis and growth (20).

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Mic for helpful discussions and the Burnham Institute Mouse Genetics Facility for animal maintenance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AA09731 (to G. D.).

The abbreviations used are: RA, retinoic acid; RALDH, retinaldehyde dehydrogenase; ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; SDR, short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase; Adh, mouse alcohol dehydrogenase gene; VAD, vitamin A deficiency/vitamin A-deficient; ES, embryonic stem; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography, WT, wild-type; P, postnatal day.

REFERENCES

- 1.Duester G. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:4315–4324. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastner P, Mark M, Chambon P. Cell. 1995;83:859–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frolik CA. In: The Retinoids. Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. Vol. 2. Orlando, FL: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Labrecque J, Dumas F, Lacroix A, Bhat PV. Biochem. J. 1995;305:681–684. doi: 10.1042/bj3050681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao D, McCaffery P, Ivins KJ, Neve RL, Hogan P, Chin WW, Dräger UC. Eur. J. Biochem. 1996;240:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0015h.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XS, Penzes P, Napoli JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16288–16293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gagnon I, Duester G, Bhat PV. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002 doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(02)00213-3. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grün F, Hirose Y, Kawauchi S, Ogura T, Umesono K. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:41210–41218. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ang HL, Duester G. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;260:227–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haselbeck RJ, Hoffmann I, Duester G. Dev. Genet. 1999;25:353–364. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:4<353::AID-DVG9>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niederreither K, Subbarayan V, Dollé P, Chambon P. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:444–448. doi: 10.1038/7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mic FA, Haselbeck RJ, Cuenca AE, Duester G. Development. 2002 doi: 10.1242/dev.129.9.2271. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosas B, Cederlund E, Torres D, Jörnvall H, Farrés J, Parés X. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:19132–19140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010478200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duester G, Farrés J, Felder MR, Holmes RS, Höög J-O, Parés X, Plapp BV, Yin S-J, Jörnvall H. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1999;58:389–395. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szalai G, Duester G, Friedman R, Jia H, Lin S, Roe BA, Felder MR. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:224–232. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boleda MD, Saubi N, Farrés J, Parés X. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;307:85–90. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z-N, Davis GJ, Hurley TD, Stone CL, Li T-K, Bosron WF. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1994;18:587–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han CL, Liao CS, Wu CW, Hwong CL, Lee AR, Yin SJ. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;254:25–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosas B, Allali-Hassani A, Martínez SE, Martras S, Persson B, Jörnvall H, Parés X, Farrés J. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:25180–25187. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910040199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molotkov A, Fan X, Deltour L, Foglio MH, Martras S, Farrés J, Parés X, Duester G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002 doi: 10.1073/pnas.082093299. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jörnvall H, Höö g JO, Persson B. FEBS Lett. 1999;445:261–264. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boerman MHEM, Napoli JL. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995;321:434–441. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chai XY, Zhai Y, Napoli JL. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:33125–33131. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gamble MV, Shang EY, Zott RP, Mertz JR, Wolgemuth DJ, Blaner WS. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:2279–2292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamamoto H, Simon A, Eriksson U, Harris E, Berson E, Dryja TP. Nat. Genet. 1999;22:188–191. doi: 10.1038/9707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Driessen CAGG, Winkens HJ, Hoffmann K, Kuhlmann LD, Janssen BPM, Van Vugt AHM, Van Hooser JP, Wieringa BE, Deutman AF, Palczewski K, Ruether K, Janssen JJM. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4275–4287. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.12.4275-4287.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deltour L, Foglio MH, Duester G. Dev. Genet. 1999;25:1–10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)25:1<1::AID-DVG1>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deltour L, Foglio MH, Duester G. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:16796–16801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.16796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamm JJ. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1982;6:652–659. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(82)70054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biesalski HK. Toxicology. 1989;57:117–161. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(89)90161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Armstrong RB, Ashenfelter KO, Eckhoff C, Levin AA, Shapiro SS. In: The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. 2nd Ed. Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS, editors. New York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1994. pp. 545–572. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson M. Br. Med. J. 1990;301:1176. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mortensen RM, Zubiaur M, Neer EJ, Seidman JG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1991;88:7036–7040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joyner AL. Gene Targeting: a Practical Approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogan B, Beddington R, Costantini F, Lacy E. Manipulating the Mouse Embryo. 2nd Ed. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang K, Bosron WF, Edenberg HJ. Gene. 1987;57:27–36. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haselbeck RJ, Duester G. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1997;21:1484–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collins MD, Eckhoff C, Chahoud I, Bochert G, Nau H. Arch. Toxicol. 1992;66:652–659. doi: 10.1007/BF01981505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Litchfield JT, Jr, Wilcoxon F. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1949;96:99–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haselbeck RJ, Ang HL, Duester G. Dev. Dyn. 1997;208:447–453. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199704)208:4<447::AID-AJA1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Algar EM, Seeley T-L, Holmes RS. Eur. J. Biochem. 1983;137:139–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts ES, Vaz ADN, Coon MJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 1992;41:427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lieber CS. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1994;32:631–681. doi: 10.3109/15563659409017974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kono H, Bradford BU, Yin M, Sulik KK, Koop DR, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, McDonald T, Dikalova A, Kadiiska MB, Mason RP, Thurman RG. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;277:G1259–G1267. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]