Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to investigate associations between John Henryism (JH) and NEO PI-R personality domains. JH—a strong behavioral predisposition to engage in high-effort coping with difficult psychosocial and economic stressors—has been associated with poor health, particularly among persons in lower socioeconomic (SES) groups. Unfavorable personality profiles have also been frequently linked to poor health; however, no studies have yet examined what global personality traits characterize JH.

METHODS

Hypotheses were examined using data from a sample of 233 community volunteers (mean age: 33 years; 61% black and 39% white) recruited specifically to represent the full range of the SES gradient. Personality (NEO PI-R) and active coping (12-item John Henryism scale) measures and covariates were derived from baseline interviews.

RESULTS

In a multiple regression analysis, independent of SES JH was positively associated with Conscientiousness (C; p<.001) and Extraversion (E; p<.001), while the combination of low JH and high SES was associated with Neuroticism (N; p=0.02) When examining associations between JH and combinations of NEO PI-R domains called “styles,” high JH was most strongly associated with a high E/high C “Go-Getters” style of activity while low JH was associated with the low E/high O “Introspectors” style. In facet level data, the most robust associations with JH were found for five C and five E facets.

CONCLUSIONS

High JH was associated with higher scores on C and E, but the combination of low JH and high SES was associated with higher scores on N.

Keywords: John Henryism, Personality, Coping, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Neuroticism

A large body of behavioral and psychosomatic research has explored the connection between stress and chronic disease, focusing primarily on the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors like hypertension (1-3). Researchers have concluded that many health problems are mediated by personality traits (4, 5) and coping behaviors (6, 7) that either buffer or augment stress effects on health.

In the mid 1980s, James (2, 8, 9) developed the concept of John Henryism (JH) to describe a strong behavioral predisposition of some individuals, especially African Americans, to use effortful, active coping as a way to overcome difficult psychosocial and economic stressors. Underpinning such effortful active coping was the belief that these difficult stressors could be overcome through hard work and determination (8). The JH hypothesis posits that such repetitive high effort coping among persons of lower socioeconomic status (SES)–persons typically lacking the resources to overcome endemic psychosocial and economic stressors–contributes to the elevated rates of hypertension among low SES individuals, especially lower SES African Americans (10). Because of its strong focus on low SES individuals, and especially low SES African Americans, the health implications of the JH coping style has been examined most extensively in African Americans (11).

Coping styles can be considered either adaptive or maladaptive with respect to preserving health (12). For example, James et al. (8) noted that high JH, in the presence of adequate social and economic coping resources, may be highly adaptive and thus correlated with positive health outcomes. In the absence of adequate coping resources, however, high JH, over time, could lead to frustration, disappointment, rumination, poor social relations, and harmful physiological arousal (8, 10, 11).

Though exceptions exist (e.g. 13), empirical findings suggest that an interaction between JH and SES is associated with increased risk for cardiovascular dysregulation (8-10, 14-18). Evidence varies in the manner in which SES interacts with JH to predict physiological markers (11); however, in studies where low SES is a reliable index of a high stress environment, individuals within these environments who routinely engage in repetitive high effort coping have been observed to have the highest prevalence of hypertension, and the highest mean diastolic blood pressure and cholesterol levels (8, 15, 16).

While high JH has been shown to be correlated with higher job satisfaction (9), higher life satisfaction (2), higher levels of social support (19) and lower levels of psychological stress (19, 20), to our knowledge no comprehensive studies have investigated relationships between JH and personality constructs that have been a major focus of psychosomatic research. Researchers have long employed personality inventories and constructs seeking to discover behavioral origins of disease. Although several models of personality exist (12, 21-23) the empirically based five-factor model of personality (24-27) provides arguably the most useful framework for the study of personality and health. This hierarchical model posits that human personality can be captured by five relatively independent domains—Neuroticism (N; a predisposition towards negative affect expressed through anxiety, depression and hostility), Extraversion (E; a desire for both a greater quantity and intensity of interpersonal interaction), Openness to Experience (O; a tendency to seek new experiences and perspectives), Agreeableness (A; a perspective that emphasizes positive qualities in others and an accommodating social presence), and Conscientiousness (C; a quality associated with persistence and attention-to-detail in goal-directed behaviors). Each of these five higher-level domains is comprised of six lower-order traits called facets. Finally, pairs of these domains can be plotted to yield 10 personality style circumplexes (24).

The five-factor model (FFM) has been researched and validated across cultures, races (28, 29), genders (30), and ages (31). In addition, studies have shown that NEO PI-R domains may be heritable (32), suggesting that they are not only behavioral descriptions but also phenotypes of temperamental tendencies towards certain cognitive and emotional patterns in behavior (33).

The scores of individuals on NEO PI-R domain scores have been associated with both behavioral and health outcomes. Higher levels of Neuroticism are associated with cardiovascular disease and mortality (34). Further, individuals who are higher on N and lower on C and A are more likely to smoke (35), those with high E, high N, low C, and low A are more likely to have motives for drinking (36), but those lower on depression, another facet of N, and higher on E are more likely to exercise (37). Increased cardiovascular reactivity to stress, a predictor of cardiovascular disease, has been found to be associated with higher levels of N facet hostility (38) and anger (39) and E (40); and, facets of O have been associated with cardiac and all-cause mortality (41).

Research suggests that although independent domains can be used as predictors of health behaviors, combinations of domains that embody distinct personality styles may be stronger predictors of health outcomes. For instance, a low N and high C personality style is associated with participation in social/relaxation activities (42), more wellness behaviors and less risk taking (43). In contrast, a high N and low C personality style has been associated with health risk behaviors, less effective coping strategies, and mortality (35, 44, 45).

Individual risky health behaviors do not occur in isolation from one another but rather occur in clusters, with more unhealthy behaviors occurring more frequently in low SES individuals (6, 46). Constellations of health risk behaviors in certain groups may be due to common personality traits or styles of coping among group members. Personality traits, such as higher hostility (47, 48), depression and hopelessness (49) and low O—traits associated with poor psychosocial functioning, less effective stress coping, and risky health behaviors—are reported to be more common among low SES groups (50).

Despite similarities between coping and personality, there is a dearth of research linking these two areas of research in any systematic manner. In the case of JH, for example, it is not clear why this particular coping style has differential associations with cardiovascular health depending on the individual's SES. One possibility is that, depending on SES, high JH is differentially associated with “at risk” personality traits, a hypothesis that can be tested by investigating associations between JH and a well understood, and well validated, global measure of personality such as the NEO PI-R.

Given the standard characterization (8, 9, 15) of individuals who score high on JH as “hard working,” “optimistic” and “energetic”, we hypothesize that high JH individuals will share domain similarities in their NEO PI-R profile, such as high C and high E overall. However, because low SES may increase the likelihood that high JH individuals will experience frustration and anger when their high effort coping is unsuccessful, SES may moderate associations between JH and various personality dimensions as measured by the NEO PI-R. Specifically, we predict that high JH in the presence of low SES will be associated with less healthy global personality traits, such as high N and some facets of E, but that high JH in the presence of high SES will be associated with global personality traits indicative of good health, such as low N and high C.

Methods

Sample

This study used data collected between 1997 and 2002 in a research program that aims to identify biobehavioral factors involved in the etiology and pathogens of CHD (51-53). The sample was recruited during a period of via newspaper ads, fliers, radio or TV announcements in the community (supermarkets, barber shops, churches, etc.), civic organizations and public events. Because clinical research has historically underrepresented minority groups, African-Americans were specifically targeted in this study in order to have approximately equal proportions of African-American and white participants. Furthermore, participants were recruited based on their income and education in order to specifically represent high and low SES groups in Durham, NC. Due to the medical requirements of the full study (i.e. spinal tap), phone interview screened out individuals who reported any previously diagnosed major long-term medical or psychological illness (e.g. diabetes, HIV, arthritis, major depression). Participants who fulfilled the initial SES eligibility criteria and gave written informed consent underwent a short screening process that included a full battery of questionnaires, blood samples and physical and psychological examination. As shown in Table 1, the final sample used for this study consisted of 233 participants, ages 18-50 (mean 33.40), with 138 high SES and 95 low SES (see below for criteria), 113 female 120 male, 141 African American and 92 whites (based on self-identification) participants. The current study included, among the 233 subjects, 68 individuals who did not complete the experimental arm of the study due to medical condition (n=28), psychiatric diagnosis (n=3), positive drug screen (n=3) and others non-health related reasons such as scheduling conflicts or drop out (n=31). Informed consent was obtained using a form approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Black/White Descriptive Statistics.

| Blacks-Mean | Std Dev | Whites-Mean | Std Dev | All-Mean | Std Dev | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEO PI-R domains | ||||||

| -Neuroticism | 51.3 | ± 7.81 | 49.99 | ± 10.08 | 50.78 | ± 8.78 |

| -Extraversion | 50.94 | ± 8.63 | 52.6 | ± 9.14 | 51.59 | ± 8.85 |

| -Conscientiousness | 47.5 | ± 10.28 | 46.87 | ± 9.26 | 47.25 | ± 9.88 |

| -Openness | 51.15 | ± 8.76 | 54.21 | ± 9.78 | 52.35 | ± 9.27 |

| -Agreeableness | 45.46 | ± 9.57 | 49.82 | ± 10.18 | 47.17 | ± 10.02 |

| John Henryism | 49.19 | ± 6.11 | 48.11 | ± 4.98 | 48.76 | ± 5.7 |

| Age | 32.11 | ± 8.8 | 35.38 | ± 8.32 | 33.4 | ± 8.75 |

| Sex | 70F/71M | 43F/49M | 113F/120M | |||

| SES | 75H/66L | 63H/29L | 138H/95L |

Measures

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

Predetermined SES criteria were used during recruitment to obtain an economically diverse community sample. Current education and household income of the participant were used to classify participants into higher SES and lower SES groups. Two categories of income were used—below or equal to $24,900 and above $24,900, which corresponded to the 40th percentile rank of household incomes in Durham County according to the 1990 Census. The low SES category includes those who had income of less than or equal to $24,900 and who had less than a college degree. The high SES group included those who had income greater than $24,900, regardless of education, or those with a college degree or more regardless of income. Full details on recruitment and SES classifications are described elsewhere (51).

John Henryism

The John Henryism Scale for Active Coping (JHAC) was used to measure to JH (10, 54). Using a five point Likert-type scale, the JHAC contains 12 items; responses for each item range from completely true (score = 5) to completely false (score =1). Total scores can thus range from a low of 12 to a high of 60, with high scores indicating a strong predisposition to engage in high effort coping with difficult and recurring socio-environmental stressors (job demands, family responsibilities, interpersonal conflict, etc). The JHAC has acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach alphas of 0.70, or greater in most studies (54).

NEO PI-R

The internal consistency of the 240-item NEO PI-R is very high. Research (24) indicates that, for each domain, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were: N (0.92), E (0.89), O (0.87), A (0.86), and C (0.90). Test-retest reliability for the domains has also been reported to be very high: 0.79, 0.79, 0.80, 0.75, 0.83 for N, E, O, A, and C, respectively. In addition to the domain scores, subjects were also characterized on style graphs. Briefly, factor domain scores1, expressed as z-scores, for any two dimensions are plotted against one another, yielding four quadrants: High on the 1st dimension, low on the 2nd (+ −), high on the 1st dimension, high on the 2nd (+ +), low on the 1st dimension, high on the 2nd (− +) and low on both dimensions (− −). Z-scores in the average range for any of the 2 dimensions (between −0.5 and 0.5) fall into an untyped, centered group. For description of all 10 styles, see Costa & Piedmont (55).

Analysis

Linear regressions were used to examine associations between continuous measures of JH and NEO PI-R domains. Non-significant higher order interactions were removed from the model. Analyses controlled for covariates race, age, and sex as recommended by James (54). Since JH and SES were strongly correlated (b=−1.62, p=0.032) in the current study, and still marginally correlated when other covariates are added to the model (b=−1.498, p=0.055), we decided to include SES among the covariates when testing the JH by NEO PI-R association. This addition also follows the suggestion of Braverman and colleagues (56) who recommend controlling for SES when studying variables influenced by race. To model the interaction between JH and SES, high SES was modeled as 1 and low SES as 0. To test the interaction, high SES and low SES were analyzed separately as criterion variables. Linear regression of NEO PI-R facets was conducted only when higher-order ANOVA NEO PI-R domain tests were significant. ANOVAs were conducted on 10 two-domain NEO PI-R style combinations, and Least Square means were computed only when higher order NEO PI-R style ANOVAs were significant. Multiple-test correction was performed using the Bonferroni correction and multiple comparison correction was performed using the Tukey-Kramer method. Analyses were conducted using SAS v.9.

Results

SES moderated the association between JH and personality domains only for N (b=−0.47, p=0.02). Within the full models including all covariates and the significant JH x SES interaction for N, women reported significantly higher N (b=4.09, p<.001) and A (b=5.51, p<.001) than men. Blacks reported lower O (b=−2.6, p=0.04) and A (b=−3.64, p=0.006) scores than Whites. Older individuals reported higher A (b=0.15, p=0.04). Higher SES subjects reported higher E (b=3.84, p=0.001), C (b=3.59, p=0.004), and O (b=2.87, p=0.02).

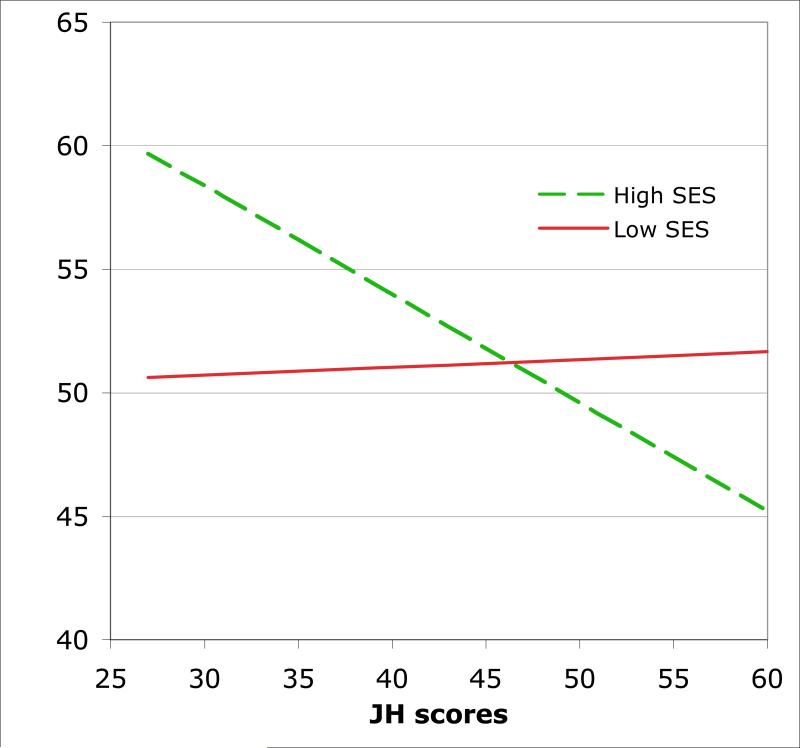

Regardless of SES, higher JH was associated with higher E (b=0.36, p<.001) and C (b=0.68, p<.001). However, as shown in Figure 1, SES moderated the association between JH and N (b for interaction=−0.47, p=0.02): among low SES individuals, mean N scores changed little as mean JH scores increased (b=0.03), whereas among high SES individuals, mean N scores decreased sharply as mean JH scores increased (b=−0.44). Of particular note, N scores for high SES individuals with low JH scores were well above the population norm of 50, while high SES individuals with high JH scores had N scores well below the population norm.

Figure 1.

Regression Lines Displaying Neuroticism scores by John Henryism scores for High and Low SES, Controlling for Age, Sex, Race and Socioeconomic Status.

To characterize this relationship in more detail, we conducted follow-up analyses testing associations between JH and facets (lower-order traits) of the larger domains E, C, and N using the Bonferroni correction (sig. at p<0.008). We restricted this analysis to E, C, and N facets since only these domains were significantly associated with JH. Since the only domain with a JH*SES interaction was N, N facets were examined only for JH*SES interactions. Although not significantly associated with JH following statistical correction, it seems that the significant JH*SES interaction at the domain level is driven by N facets Hostility (b=−0.60 p=0.01) and Self-Consciousness (b=−0.46, p=0.03). As also shown in Table 2, JH as a main effect was significantly associated with ten facets: E facets Warmth, Assertiveness, Activity, Excitement-Seeking, and Positive Emotion and C facets Competence, Dutifulness, Achievement Striving, Self-Discipline and Deliberation.

Table 2.

Effect of John Henryism on NEO PI-R Facets Controlling for Age, Sex, Race, and Socioeconomic Status.

| Main Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C facets | b | p-value | E facets | b | p-value |

| Competence | 0.63 | <.001 | Warmth | 0.48 | <.001 |

| Order | 0.25 | 0.02 | Gregarious | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| Dutifulness | 0.76 | <.001 | Assertiveness | 0.51 | <.001 |

| Achievement striving | 0.63 | <.001 | Activity | 0.35 | <.001 |

| Self-Discipline | 0.55 | <.001 | Excitement-seek | 0.32 | 0.001 |

| Deliberation | 0.39 | <.001 | Pos Emotion | 0.38 | 0.001 |

Note: bolded facets are significant at Bonferroni correction level of p=0.008

We next analyzed the relationship between JH scores and NEO PI-R style groups. Among the ten possible two-domain combinations, four combinations revealed a significant ANOVA test adjusted by the Bonferroni correction (p=0.005): EC (p<.001), EO (p<.001), OC (p<.001), NE (p<.001), AC (p=0.002), and NC (p=0.002). Further pairwise comparisons of these means using the Tukey-Kramer correction revealed that only one style, high E/high C was significantly different from other styles in each group after correction (Table 3). The high E/high C style of activity, or the “Go-Getters,” was significantly higher on JH (M=52.09) than all other E and C combinations (E+C−, p=0.008; E−C+, p=0.02; E−C−, p<.001), and also had the highest mean among all possible 50 quintiles. In contrast, the low E/high O style or the “Introspectors” group, was lower on JH (M=45.54) than other E and O combinations, marginally lower than E−O−, (E+O−, p=0.02; E+O+, p<.001; E−O−, p=0.07), and also had the lowest mean among all possible 50 quintiles.

Table 3.

John Henryism Scores for the Six Significant NEO PI-R Personality Styles, Controlling for Age, Sex, Race and Socioeconomic Status.

| NC Combinations | N | Mean | std err | EC Combinations | N | mean | std err |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undercontrolled N+C− | 73 | 47.54 | 0.66 | Funlovers E+C− | 56 | 47.88 | 0.82 |

| Overcontrolled N+C+ | 39 | 49.50 | 0.90 | Go-getters E+C+ | 50 | 52.09 | 0.79 |

| Directed N−C+ | 33 | 51.78 | 0.10 | Plodders E−C+ | 18 | 47.41 | 1.28 |

| Relaxed N−C− | 52 | 47.60 | 0.77 | Lethargic E−C− | 63 | 46.97 | 0.70 |

| NE Combinations | N | Mean | std err | AC Combinations | N | mean | std err |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloomy pessimists N+E− | 51 | 47.37 | 0.87 | Well-intentioned A+C− | 41 | 46.57 | 0.89 |

| Overly emotional N+E+ | 57 | 48.80 | 0.74 | Effective altruists A+C+ | 35 | 51.20 | 0.95 |

| Upbeat optimists N−E+ | 52 | 51.09 | 0.80 | Self-promoters A−C+ | 42 | 50.35 | 0.88 |

| Low-keyed N−E− | 31 | 46.43 | 1.00 | Undistinguished A−C− | 88 | 48.20 | 0.63 |

| OC Combinations | N | Mean | std err | EO Combinations | N | Mean | std err |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreamers O+C− | 64 | 46.80 | 0.69 | Mainstream consumers E+O− | 35 | 49.28 | 0.94 |

| Good students O+C+ | 56 | 50.68 | 0.76 | Creative interactors E+O+ | 80 | 50.07 | 0.65 |

| By-the-bookers O−C+ | 21 | 51.42 | 1.20 | Introspectors E−O+ | 36 | 45.29 | 0.92 |

| Reluctant scholars O−C− | 64 | 48.10 | 0.72 | Homebodies E−O− | 48 | 48.54 | 0.82 |

Note: bolded means are significantly different from other styles within group. Centered quintile is not included.

Discussion

Contrary to expectations, the association between JH and personality was moderated by SES only for the N domain. After controlling for demographic variables, JH was positively associated with E and C as predicted, but only as a main effect. Also, contrary to expectations, it was not the combination of low SES and high JH that was most strongly associated with high N; rather, it was the combination of high SES and low JH. As Figure 1 shows, N changed little in low SES subjects as JH increased, but declined significantly among high SES subjects as JH increased.

In this study, the combination of high SES and high JH was associated with a generally healthy personality profile, specifically low N, high C and high E. However, the combination of low JH and high SES was associated with high N in this sample. As previously noted, the low N and high C personality style has been associated with increased participation in relaxation activities (42), more wellness behaviors and less risk taking (43). Other studies have noted the benefit of high JH among those with high SES vis-à-vis blood pressure (9, 14, 17, 57), and Bonham, Sellers and Neighbors (58) reported that high JH in a sample of high SES African-American men was associated with better self-reported physical health as measured by the short form health survey (SF-12). This latter finding was recently replicated among Asian immigrants to the US, in that higher JH was associated with both higher self-rated health and physical functioning (20).

Our premise that high JH coupled with high SES is associated with positive personality characteristics is consistent with published findings from community studies of JH showing that the most favorable cardiovascular health profile is usually found for persons (especially, but not exclusively for African Americans – see (59)) who are high in both SES and JH (8, 14-16, 19). In contrast, low JH coupled with high SES could be problematic since, at least in this sample, it was associated with lower C and E plus greater N, the latter a putative marker of impaired psychological health.

The combination of low JH and high SES may not be associated solely with poorer psychological health (e.g. higher N). In the Pitt County Study, for example, James et al. (19) found that high SES African American men who scored low on JH had higher levels of perceived stress, and correspondingly, higher levels of hypertension. Hence, low JH scores may indicate a low (or deteriorating) sense of environmental mastery resulting from past unsuccessful high-effort coping by high SES men. This issue warrants further study.

In addition to the health-damaging effects of the combination of high N and low C, high N levels alone could contribute to risk for poor health. The high SES/low JH individuals in this study reported N values in the ‘high’ range (1 SD greater than population average), a particularly important finding considering that N has been associated with health risk in previous research. High N may indicate a predisposition to engage in unhealthy behaviors and even early mortality (34, 36, 60-62). A body of research suggests that N is related to a variety of diseases and disabilities from depression, and pain conditions to eating disorders, psychosomatic complaints and poor coping (63-66). Additional research suggests that those high in N are more likely to exhibit medical conditions of the tension type such as migraine, neck pain and high blood pressure (67).

Neuroticism is a broadly defined construct with several facets. Our study found that N facets Hostility and Self-Consciousness were the primary drivers of the JH*SES interaction, and both have been shown to be predictors of important health outcomes and health behaviors. Hostility has consistently been associated with an unhealthy lifestyle (e.g., obesity, social isolation), fasting glucose and insulin sensitivity, and increased risk of cardiac and all-cause mortality (53, 68-70). While fewer studies have looked at the effect of Self-Consciousness, some suggest that it may be an important moderator of destructive drinking behavior (71, 72) and of subsequent illness for those with previous stress (73), and it may be a significant predictor of social phobia (74), of subjective memory impairment (75), of irritable bowel syndrome (76), and of exercise (77, 78). Thus, while it is likely that the combined effect of high SES and low JH increases one's risk for certain poor health outcomes, future research is needed to determine if the high N facets, Hostility and Self-Consciousness, account for any observed excess health risks in this group.

This study provides evidence that the same qualities (e.g., high E and high C) previously found to be associated with longevity, even when controlled for smoking and obesity (60, 79-81) are also associated with high JH. This suggests that high JH alone, regardless of SES, could be positively associated with longevity. On the other hand, low JH may be unfavorable to health since it is associated with lower C and E. In this study, C facets Competence, Dutifulness, Achievement Striving, Self-Discipline, and Deliberation as well as E facets Warmth, Assertiveness, Activity, Excitement-Seeking and Positive Emotion were drivers of the significant association between C and E domains and JH.

Finally, our analysis of the relationship between JH and NEO PI-R styles revealed some interesting profiles. Individuals high on JH were more likely to have a high E/high C style of impulse control referred to as “Go Getters.” The latter, according to Costa & McCrae (55), are productive and efficient workers who set a fast pace. They know what is necessary and are eager to contribute. They might design their own plan of action and follow it dutifully. They may also come across as bossy by imposing their style of working on others (55).

Individuals low on JH were observed to exhibit the low E/high O “Introspectors” style (55). Introspectors have interests that center on activities that they can perform alone; individual creative hobbies like painting and music or non-creative hobbies like reading and writing often appeal to this group. Importantly, the current study found that the interaction between JH and SES had a similar effect on N for blacks and whites living in the same geographic region. Whereas most prior health studies of JH, or the JH*SES interaction, have been conducted on all African American samples (11), it is not known whether the same relationship between SES and JH vis-à-vis important health measures would be found in racially diverse populations living in the same geographic area. Our inclusion of both whites and blacks in this study is thus a major strength of the current study.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, and though the 233 study participants varied in terms of demographics (high and low SES groups), personality and coping features, some of our findings may have failed to reach statistical significance because of low statistical power for the low SES group (n=95). A second potential limitation was our decision to use a composite SES measure, and to dichotomize it for analysis, instead of using separate continuous measures for education and income. Our dichotomized SES measure may not have represented the full range of possible SES categories. However, other studies have emphasized difficulty in isolating and measuring SES experimentally and the lack of consensus on the best method for measuring SES (56, 82-84). Furthermore, our criteria for defining high and low SES were predetermined and used in the study design to recruit relatively equal numbers of high and low SES participants based on both their education and income.

Although JH correlates in interesting ways with the NEO PI-R, we do not view the two constructs/instruments as interchangeable. Each has its own theoretical and measurement history, and each is likely to be differentially predictive of a range of important health behaviors and health outcomes. The current study aimed to identify health-relevant dimensions of personality that contribute to variation in JH scores, a step viewed as appropriate to develop a fuller understanding of the multiple pathways through which JH might influence the well known inverse gradient between SES and health (10, 11, 85).

In conclusion, this study is the first systematic investigation of the relationship between the JH construct and global personality traits. Findings from this study provide some explanation for the frequently observed JH by SES effect on physiological health outcomes. Conditional on replicating our findings in other populations, especially in longitudinal studies, it should become increasingly possible to design early behavioral interventions targeting individuals who over-rely on persistent high-effort coping as a tactic for managing chronic life stressors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant P01HL36587, National Institute of Mental Health grant K05MH79482, Clinical Research Unit grant M01RR30, and the Duke University Behavioral Medicine Research Center. We thank Dr. Ilene Siegler for comments on an earlier version of this ms.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SES

Socioeconomic Status

- JH

John Henryism

- N

Neuroticism

- C

Conscientiousness

- E

Extraversion

- A

Agreeableness

- O

Openness

Footnotes

The formulas for computing the domain factor scores utilize scoring weights from each of the 30 facets to estimate each of the factor domain scores which are more nearly orthogonal than the domain scores yielded by summing the 6 facet scales in each domain. Formulas to calculate factor scores are provided in Table 2 of the NEO PI-R Professional Manual (24, p. 8).

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Anderson NB. Levels of analysis in health science. A framework for integrating sociobehavioral and biomedical research. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:563–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James SA. Psychosocial precursors of hypertension: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. Circulation. 1987;76:I60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams RB. Psychosocial and biobehavioral factors and their interplay in coronary heart disease. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:349–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Loon AJM, Tijhuis M, Surtees PG, Ormel J. Personality and coping: Their relationship with lifestyle risk factors for cancer. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;31:541–53. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avia MD, Sanz J, Sanchez-Bernardos ML, Martinez-Arias MR, et al. The five-factor model--II. Relations of the NEO-PI with other personality variables. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;19:81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger PM, Chang VW. Being poor and coping with stress: health behaviors and the risk of death. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:889–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsenkova VK, Dienberg Love G, Singer BH, Ryff CD. Coping and positive affect predict longitudinal change in glycosylated hemoglobin. Health Psychol. 2008;27:S163–71. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2(Suppl.).S163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James SA, Hartnett SA, Kalsbeek WD. John Henryism and blood pressure differences among black men. J Behav Med. 1983;6:259–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01315113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James SA, LaCroix AZ, Kleinbaum DG, Strogatz DS. John Henryism and blood pressure differences among black men. II. The role of occupational stressors. J Behav Med. 1984;7:259–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00845359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James SA. John Henryism and the health of African-Americans. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1994;18:163–82. doi: 10.1007/BF01379448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett GG, Merritt MM, Sollers JJ, III, Edwards CL, Whitfield KE, Brandon DT, Tucker RD. Stress, coping, and health outcomes among African-Americans: A review of the John Henryism hypothesis. Psychol Health. 2004;19:369–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TW, MacKenzie J. Personality and risk of physical illness. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:435–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKetney EC, Ragland DR. John Henryism, education, and blood pressure in young adults. The CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143:787–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Light KC, Brownley KA, Turner JR, Hinderliter AL, Girdler SS, Sherwood A, Anderson NB. Job status and high-effort coping influence work blood pressure in women and blacks. Hypertension. 1995;25:554–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.James SA, Strogatz DS, Wing SB, Ramsey DL. Socioeconomic status, John Henryism, and hypertension in blacks and whites. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:664–73. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wist WH, Flack JM. A test of the John Henryism hypothesis: cholesterol and blood pressure. J Behav Med. 1992;15:15–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00848375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Markovic N, Bunker CH, Ukoli FA, Kuller LH. John Henryism and blood pressure among Nigerian civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:186–90. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright LB, Treiber FA, Davis H, Strong WB. Relationship of John Henryism to cardiovascular functioning at rest and during stress in youth. Ann Behav Med. 1996;18:146–50. doi: 10.1007/BF02883390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James SA, Keenan NL, Strogatz DS, Browning SR, Garrett JM. Socioeconomic status, John Henryism, and blood pressure in black adults. The Pitt County Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:59–67. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haritatos J, Mahalingam R, James SA. John Henryism, self-reported physical health indicators, and the mediating role of perceived stress among high socioeconomic status Asian immigrants. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1192–203. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarus RS. Stress and emotion : a new synthesis. Springer Pub. Co.; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eysenck HJ. Personality and Cancer. In: Cooper CL, editor. Handbook of Stress, Medicine and Health. CRC Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenman RH. Handbook of Stress, Medicine and Health. CRC Press; New York: 1996. Personality, Behavior Patterns, and Heart Disease. In Cooper CL editor. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costa PT, Jr., McCrea RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Digman JM. Personality structure: Emergence of the five-factor model. Annu Rev Psychol. 1990;41:417–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.John OP. The “Big Five” factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural languages and in questionnaires. In: Pervin LA, editor. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. Guilford Press; New-York: 1990. pp. 66–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Trait Explanations in Personality Psychology. Eur J Pers. 1995;9:231–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCrae RR, Costa PT., Jr Personality trait structure as a human universal. Am Psychol. 1997;52:509–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.52.5.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savla J, Davey A, Costa PT, Jr., Whitfield KE. Replicating the NEO-PI-R factor structure in African-American older adults. Pers Individ Dif. 2007;43:1279–88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa PT, Jr., Terracciano A, McCrae RR. Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: robust and surprising findings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:322–31. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roepke S, McAdams LA, Lindamer LA, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Personality profiles among normal aged individuals as measured by the NEO-PI-R. Aging Ment Health. 2001;5:159–64. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heath AC, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Eaves LJ, Kendler KS. Evidence for genetic influences on personality from self-reports and informant ratings. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:85–96. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa PT, Jr., McCrae RR. Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. J Pers Assess. 1995;64:21–50. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shipley BA, Weiss A, Der G, Taylor MD, Deary IJ. Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey: a 21-year prospective cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:923–31. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815abf83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terracciano A, Costa PT., Jr Smoking and the Five-Factor Model of personality. Addiction. 2004;99:472–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1844–57. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegler IC, Blumenthal JA, Barefoot JC, Peterson BL, Saunders WB, Dahlstrom WG, Costa PT, Jr., Suarez EC, Helms MJ, Maynard KE, Williams RB. Personality factors differentially predict exercise behavior in men and women. Womens Health. 1997;3:61–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suarez EC, Harlan E, Peoples MC, Williams RB., Jr Cardiovascular and emotional responses in women: the role of hostility and harassment. Health Psychol. 1993;12:459–68. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.6.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siegman AW, Anderson R, Herbst J, Boyle S, Wilkinson J. Dimensions of anger-hostility and cardiovascular reactivity in provoked and angered men. J Behav Med. 1992;15:257–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00845355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pearson GL, Freeman FG. Effects of extraversion and mental arithmetic on heart-rate reactivity. Percept Mot Skills. 1991;72:1239–48. doi: 10.2466/pms.1991.72.3c.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jonassaint CR, Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Siegler IC, Barefoot JC. Facets of openness predict mortality in patients with cardiac disease. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:319–22. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318052e27d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marks GR, Lutgendorf SK. Perceived health competence and personality factors differentially predict health behaviors in older adults. J Aging Health. 1999;11:221–39. doi: 10.1177/089826439901100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Booth-Kewley S, Vickers RR., Jr Associations between major domains of personality and health behavior. J Pers. 1994;62:281–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1994.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernard NS, Dollinger SJ, Ramaniah NV. Applying the big five personality factors to the impostor phenomenon. J Pers Assess. 2002;78:321–33. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7802_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Personality and mortality in old age. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59:P110–6. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.3.p110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychol Bull. 2003;129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubzansky LD, Kawachi I, Sparrow D. Socioeconomic status, hostility, and risk factor clustering in the Normative Aging Study: any help from the concept of allostatic load? Ann Behav Med. 1999;21:330–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02895966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barefoot JC, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Siegler IC, Anderson NB, Williams RB., Jr Hostility patterns and health implications: correlates of Cook-Medley Hostility Scale scores in a national survey. Health Psychol. 1991;10:18–24. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Harper S, Lynch J, Hsu WL, Everson SA, Hillemeier MM, Raghunathan TE, Salonen JT, Kaplan GA. Life course socioeconomic conditions and adult psychosocial functioning. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korner A, Geyer M, Gunzelmann T, Brahler E. The influence of socio-demographic factors on personality dimensions in the elderly. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2003;36:130–7. doi: 10.1007/s00391-003-0085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Burroughs AR, Visscher WA, Haney TL, Efland JR, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, Jr., Siegler IC. Community recruitment process by race, gender, and SES gradient: lessons learned from the Community Health and Stress Evaluation (CHASE) Study experience. J Community Health. 2003;28:421–37. doi: 10.1023/a:1026029723762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams RB, Marchuk DA, Gadde KM, Barefoot JC, Grichnik K, Helms MJ, Kuhn CM, Lewis JG, Schanberg SM, Stafford-Smith M, Suarez EC, Clary GL, Svenson IK, Siegler IC. Serotonin-related gene polymorphisms and central nervous system serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:533–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Surwit RS, Williams RB, Siegler IC, Lane JD, Helms M, Applegate KL, Zucker N, Feinglos MN, McCaskill CM, Barefoot JC. Hostility, race, and glucose metabolism in nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:835–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.James SA. The John Henryism scale. In: Jones RL, editor. Handbook of tests and measurements for black populations. Cobb & Henry Publishers; Hampton, VA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Costa PT, Jr., Piedmont RL. Interpretation of Revised NEO Personality Inventory Profiles of Madeline G: Self, Partner, and an Integrated Perspective. In: Wiggins JS, editor. Paradigms of Personality Assessment. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, Posner S. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernander AF, Duran RE, Saab PG, Schneiderman N. John Henry Active Coping, education, and blood pressure among urban blacks. J Natl Med Assoc. 2004;96:246–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bonham VL, Sellers SL, Neighbors HW. John Henryism and self-reported physical health among high-socioeconomic status African American men. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:737–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duijkers TJ, Drijver M, Kromhout D, James SA. “John Henryism” and blood pressure in a Dutch population. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:353–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198807000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terracciano A, Lockenhoff CE, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, Costa PT., Jr Personality predictors of longevity: activity, emotional stability, and conscientiousness. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:621–7. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31817b9371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Viken RJ, Rose RJ, Morzorati SL, Christian JC, Li TK. Subjective intoxication in response to alcohol challenge: heritability and covariation with personality, breath alcohol level, and drinking history. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:795–803. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067974.41160.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Terracciano A, Lockenhoff CE, Crum RM, Bienvenu OJ, Costa PT., Jr Five-Factor Model personality profiles of drug users. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O'Brien TB, DeLongis A. The interactional context of problem-, emotion- and relationship-focused coping: The role of the big five personality factors. J Pers. 1996;64:775–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kentle RL. Headache symptomology and neuroticism in a college sample. Psychol Rep. 1989;65:976–8. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1989.65.3.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis C. Normal and neurotic perfectionism in eating disorders: An interactive model. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;22:421–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199712)22:4<421::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Costa PT., Jr Influence of the normal personality dimension of neuroticism on chest pain symptoms and coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1987;60:20J–6J. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)90679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson M. The vulnerability status of neuroticism: over-reporting or genuine complaints? Pers Individ Dif. 2003;35:877–87. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Barefoot JC. Hostility, age, and mortality in a sample of cardiac patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:64–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC. Hostility as a predictor of survival in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:629–32. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138122.93942.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siegler IC, Costa PT, Jr., Brummett BH, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, Dahlstrom WG, Kaplan BH, Vitaliano PP, Nichaman MZ, Day RS, Rimer BK. Patterns of change in hostility from college to midlife in the UNC Alumni Heart Study predict high-risk status. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:738–45. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000088583.25140.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Labrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C. Self-consciousness moderates the relationship between perceived norms and drinking in college students. Addict Behav. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.LaBrie J, Pedersen ER, Neighbors C, Hummer JF. The role of self-consciousness in the experience of alcohol-related consequences among college students. Addict Behav. 2008;33:812–20. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Suls J, Fletcher B. Self-attention, life stress, and illness: a prospective study. Psychosom Med. 1985;47:469–81. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198509000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fehm L, Hoyer J, Schneider G, Lindemann C, Klusmann U. Assessing post-event processing after social situations: a measure based on the cognitive model for social phobia. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21:129–42. doi: 10.1080/10615800701424672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pearman A, Storandt M. Self-discipline and self-consciousness predict subjective memory in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60:P153–7. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.3.p153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park KS, Ahn SH, Hwang JS, Cho KB, Chung WJ, Jang BK, Kang YN, Kwon JH, Kim YH. A survey about irritable bowel syndrome in South Korea: prevalence and observable organic abnormalities in IBS patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:704–11. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sin MK, LoGerfo J, Belza B, Cunningham S. Factors influencing exercise participation and quality of life among elderly Korean Americans. J Cult Divers. 2004;11:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dergance JM, Calmbach WL, Dhanda R, Miles TP, Hazuda HP, Mouton CP. Barriers to and benefits of leisure time physical activity in the elderly: differences across cultures. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:863–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iwasa H, Masui Y, Gondo Y, Inagaki H, Kawaai C, Suzuki T. Personality and all-cause mortality among older adults dwelling in a Japanese community: a five-year population-based prospective cohort study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16:399–405. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181662ac9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weiss A, Costa PT., Jr Domain and facet personality predictors of all-cause mortality among Medicare patients aged 65 to 100. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:724–33. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000181272.58103.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fry PS, Debats DL. Perfectionism and the Five-factor Personality Traits as Predictors of Mortality in Older Adults. J Health Psychol. 2009;14:513–24. doi: 10.1177/1359105309103571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andresen EM, Miller DK. The future (history) of socioeconomic measurement and implications for improving health outcomes among African Americans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1345–50. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.10.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shavers VL. Measurement of socioeconomic status in health disparities research. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1013–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams DR. Race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status: measurement and methodological issues. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26:483–505. doi: 10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health. The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]