Abstract

Ceramides with different fatty acyl chains may vary in their physiological or pathological roles; however, it remains unclear how cellular levels of individual ceramide species are regulated. Here, we demonstrate that our previously cloned human alkaline ceramidase 3 (ACER3) specifically controls the hydrolysis of ceramides carrying unsaturated long acyl chains, unsaturated long-chain (ULC) ceramides. In vitro, ACER3 only hydrolyzed C18:1-, C20:1-, C20:4-ceramides, dihydroceramides, and phytoceramides. In cells, ACER3 overexpression decreased C18:1- and C20:1-ceramides and dihydroceramides, whereas ACER3 knockdown by RNA interference had the opposite effect, suggesting that ACER3 controls the catabolism of ULC ceramides and dihydroceramides. ACER3 knockdown inhibited cell proliferation and up-regulated the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1. Blocking p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation attenuated the inhibitory effect of ACER3 knockdown on cell proliferation, suggesting that ACER3 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation because of p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation. ACER3 knockdown inhibited cell apoptosis in response to serum deprivation. ACER3 knockdown up-regulated the expression of the alkaline ceramidase 2 (ACER2), and the ACER2 up-regulation decreased non-ULC ceramide species while increasing both sphingosine and its phosphate. Collectively, these data suggest that ACER3 catalyzes the hydrolysis of ULC ceramides and dihydroceramides and that ACER3 coordinates with ACER2 to regulate cell proliferation and survival.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Fatty Acid, Membrane Proteins, siRNA, Sphingolipid, Ceramidase, Ceramide, Proliferation, Unsaturated Acyl Chain, p21CIP1/WAF1

Introduction

Ceramidases catalyze the hydrolysis of ceramides to form free fatty acids and sphingosine (SPH)3 (1), and as such they are important intermediates of complex sphingolipids that play an important role in the integrity and function of cell membranes. Ceramides also act as bioactive molecules to mediate various cellular responses such as cell growth arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis in response to a variety of stress stimuli, including the cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (2), cancer chemotherapeutic agents (3), UV (4), and ionizing radiation (5). Similar to ceramides, SPH also potently induces cell growth arrest, differentiation, or apoptosis (6, 7). SPH is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases to generate sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) (8, 9). In contrast to ceramides and SPH, S1P mainly promotes cell proliferation and survival (10). Therefore, ceramidases may play an important role in regulating the levels of ceramides, SPH, and S1P as well as cellular responses mediated by these bioactive lipids.

Ceramidases, according to their pH optima for in vitro activity, are classified into acid, neutral, and alkaline types (1, 11). Five human ceramidases encoded by five distinct genes have been identified as follows: the acid ceramidase (ASAH1) (12); neutral ceramidase (ASAH2) (13); alkaline ceramidase 1 (ACER1/ASAH3 (14); alkaline ceramidase 2 (ACER2/ASAH3L) (15); and alkaline ceramidase 3 (ACER3/APHC/PHCA) (16).

Ceramidases have different cellular localizations and substrate specificities. ASAH1 is a lysosomal ceramidase that uses medium-chain (C10–14) ceramides as its best substrates, and it hydrolyzes C18:1- or C18:2-ceramide more efficiently than C18:0-ceramide (17). ASAH2 is localized to the plasma membrane or secreted from cells (18). ASAH2 prefers long-chain (C16–22) to very long-chain (≥C24) ceramides as substrates (19). ACER1 is an endoplasmic reticulum ceramidase that only uses very long-chain ceramides as substrates and hydrolyzes the unsaturated very long-chain C24:1-ceramide more efficiently than the saturated very long-chain C24:0-ceramide (14). ACER2 is a Golgi ceramidase that uses both long-chain and very long-chain ceramides as substrates (15).4

Different ceramidases have distinct roles in regulating cellular responses likely due to the differences in their cellular localizations and substrate specificities. A genetic deficiency in ASAH1 causes Farber disease, a sphingolipid storage disease (20, 21), suggesting an important role in sphingolipid catabolism. Recent studies showed that ASAH1 expression is increased in prostate tumors and that its up-regulation may promote tumor cell growth and survival by decreasing ceramide (22). Wu et al. (23) showed that ASAH2 protein is decreased in gemcitabine-treated cells and that its knockdown by RNAi induces cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase, suggesting that ASAH2 plays a role in cell proliferation. In contrast to ASAH1 and ASAH2, ACER1 helps mediate growth arrest and differentiation of epidermal keratinocytes (major epidermal cell type) (14). Depending on its expression level, ACER2 plays a role in either cell proliferation or growth arrest (15). Low ACER2 expression promotes cell proliferation likely through decreasing ceramide and increasing S1P, whereas high expression induces cell growth arrest because of an accumulation of SPH in cells.

ACER3 was the first mammalian alkaline ceramidase to be cloned by our group (16), but its roles in regulating the metabolism of sphingolipids and cellular responses remain unclear. ACER3 is localized to both the Golgi complex and ER, and it is highly expressed in various tissues compared with the other two alkaline ceramidases (16). We previously showed that ACER3 hydrolyzes a synthetic ceramide analogue d-ribo-C12-NBD-phytoceramide in vitro; thus, it is formerly referred to as the human alkaline phytoceramidase (haPHC) (16). However, its natural ceramide substrates remain to be identified.

In this study, we investigate the roles of ACER3 in sphingolipid metabolism and signaling. We show that ACER3 catalyzes the hydrolysis of specific ceramides/dihydroceramides/phytoceramides carrying unsaturated long acyl chains (C18:1, C20:1, or C20:4), so-called unsaturated long-chain (ULC) ceramides/dihydroceramides/phytoceramides. With quantitative (q) PCR in conjunction with alkaline ceramidase activity assays, we show that ACER3 is highly expressed in various cell types. We further illustrate that ACER3 plays a role in cell proliferation by regulating the hydrolysis of ULC ceramides and dihydroceramides in cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Minimal essential medium, Epilife medium, medium 200, human mammary epithelium cell medium, fetal bovine serum, trypsin/EDTA, phosphate-buffered saline, and penicillin/streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen. Antibodies against β-actin, GM130 (a membrane-bound protein in the Golgi complex), and p21CIP1/WAF1 were from BD Biosciences. Antibodies against poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and cleaved caspase 3 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Yeast minimal synthetic defined base containing dextrose (SD base/glu), minimal synthetic defined base containing galactose and raffinose (SD base/gal/raf), and dropout supplement lacking uracil (Ura DO) were purchased from Clontech. d-e-C20:1 and C20:4-ceramides, d-e-C18:1, C20:1, C20:4-dihydroceramides, d-ribo-C16:0, C18:1, C20:1, and C20:4-phytoceramides were synthesized in the Lipidomics Core Facility at the Medical University of South Carolina as described previously (24). Other ceramides, dihydroceramides, phytoceramides, sphingoid bases, and their phosphates were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Other unlisted chemicals were from Sigma.

Cell Culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells, aortic smooth muscle cells, neonatal epidermal keratinocytes, and mammary epithelial cells were purchased from Invitrogen and cultured in Epilife medium, Medium 200, Medium 231, and human mammary epithelium cell medium, respectively, according to the manufacturer's instructions. HSC-1 cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma cells were purchased from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (Shinjuku, Japan) and cultured in minimal essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Foreskin fibroblast cells (DFB), a kind gift of Dr. Maria Trojanowska at the Medical University of South Carolina, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum.

Assessment of Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was determined by BrdUrd incorporation assays using cell proliferation ELISA kits (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells in microplates were labeled for 12 h with the BrdUrd reagent at 37 °C before labeling medium was removed by vacuum aspiration. The cells were then fixed in the FixDenat solution for 30 min at room temperature before being washed three times with the washing buffer and then incubated with anti-BrdUrd antibody peroxidase conjugate (anti-BrdUrd-POD) for 60 min at room temperature. The microplates were washed three times with the washing buffer before the cells were incubated with 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate solution for 20 min at room temperature. Finally, the absorbance at λ450 nm in each well of the microplates was recorded on a microplate reader.

Assessment of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was determined using cell death detection ELISA kits (Roche Applied Science), which quantitatively detect apoptotic nucleosomes in the cytoplasm, i.e. DNA fragmentation. Cells in microplates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline before being lysed for 30 min at room temperature in lysis buffer (from the kit). Microplates were centrifuged for 10 min at 200 × g at room temperature, and aliquots of the supernatants (cell lysates) were transferred to streptavidin-coated microplates (from the kit) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with the immune reagent containing an anti-DNA antibody conjugated with peroxidase and anti-histone antibody conjugated with biotin. Microplates were washed three times with the kit incubation buffer before incubation (15 min at room temperature) with the kit peroxidase substrate 2,2′-azinobis[3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid]-diammonium salt in the kit substrate buffer. The absorbance at λ405 nm was measured in each cell sample on the microplate reader.

qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from various cell types using RNeasy kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Five μg of total RNA from each cell sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA as described previously (25). qPCR was performed on an iCycler system (Bio-Rad) using the following primer pairs: 5′-TGATGCTTGACAAGGCACCA-3′/5′-GGCAATTTTTCATCCACCACC-3′ for ACER1; 5′-AGTGTCCTGTCTGCGGTTACG-3′/5′-TGTTGTTGATGGCAGGCTTGAC-3′ for ACER2; 5′-CAATGTTCGGTGCAATTCAGAG-3′/5′-GGATCCCATTCCTACCACTGTG-3′ for ACER3; and 5′-CAATGTTCGGTGCAATTCAGAG-3′/5′- GGATCCCATTCCTACCACTGTG-3′ for β-actin. Standard reaction volume was 25 μl, including 12.5 μl of iQTM SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad), 10 μl of cDNA template, and 2.5 μl of a primer mixture. The initial PCR step was 3 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of a 10-s melting at 95 °C and a 45-s annealing/extension at 60 °C. The final step was 1 min of incubation at 60 °C. All reactions were performed in triplicate. qPCR results were analyzed using Q-Gene software that expresses data as mean normalized expression (26). Mean normalized expression is directly proportional to the amount of mRNA of the target gene ACER3 relative to the amount of mRNA of the reference gene (β-actin).

ACER3 Expression in Yeast Cells

ACER3 was expressed in Δypc1Δydc1 yeast mutant cells as described in our previous study (16). The Δypc1Δydc1 yeast strain lack endogenous yeast alkaline ceramidase activity because of disruption of both the yeast alkaline ceramidases YPC1 and YDC1 genes. The Δypc1Δydc1YES2 and Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 strains were obtained by transforming Δypc1Δydc1 with the yeast expression empty vector pYES2 and an ACER3 expression construct pYES2-ACER3, respectively. These yeast stains were maintained in SD-glu medium containing Ura DO supplement. ACER3 expression in Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 was induced in SD-gal/raf medium containing Ura DO supplement.

ACER3 Overexpression in Mammalian Cells

The coding sequence of the FLAG-tagged ACER3 was subcloned into pcDNA3 from the plasmid pYES2-FLAG-aPHC (ACER3), which was previously constructed (16). The resulting ACER3 expression construct, pcDNA3-ACER3, directs the expression of ACER3 tagged with FLAG at the N terminus in mammalian cells. HSC-1 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ACER3 using the transfection reagent Effectene (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, HSC-1 cells were plated onto 10-cm culture plates at a density of 105 cells/ml. The next day, a pcDNA3 DNA/Effectene or pcDNA3-ACER3 DNA/Effectene mixture was added dropwise to HSC-1 cells in the culture plates, which were gently rocked. At 48–72 h post-transfection, HSC-1 cells were harvested for Western blot analyses, alkaline ceramidase activity assays, or ESI/MS/MS analyses.

RNA Interference

A control siRNA (siCON, 5′-UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUACUU-3′ (sense)/5′-GUAUCUCUUCAUAGCCUUAUU-3′ (antisense)) and ACER3-specific siRNA number 1 (siACER3-1, 5′-UGGGAUCCUGGUGCUUCCA-3′ (sense)/5′-UGGAAGCACCAGGAUCCCA-3′ (antisense)) and number 2 (siACER3-1, 5′-CUACUCCGUGACCUGGUACUU-3′ (sense)/5′-GUACCAGGUCACGGAGUAGUU (antisense)) were synthesized at Dharmacon, Inc. (Chicago). A predesigned and validated p21CIP1/WAF1 siRNA (sip21) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. siRNA transfection was performed with Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) as described in our previous study (15).

Protein Concentration Determination

Protein concentrations were determined with bovine serum albumin as a standard using a BCA protein determination kit (Thermo Scientific; Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed essentially as described previously (15). Briefly, proteins separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membranes, which were blocked for 1 h with 10% (w/v) defatted milk in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 2, PBST. The blocked NC membranes were then incubated for 1–2 h with a primary antibody at an appropriate dilution. After thorough washing with PBST, the NC membranes were incubated for 1 h with a secondary antibody coupled with horseradish peroxidase. The NC membranes were washed with PBST four times, 15 min each, before protein bands labeled by horseradish peroxidase on the NC membranes were detected by an ECL plus system (GE Healthcare) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Ceramidase Activity Assay

Ceramidase activity was determined by the release of SPH, dihydrosphingosine, or phytosphingosine (PHS) from ceramides, dihydroceramides, and phytoceramides, respectively, as described previously (15). Briefly, a substrate was dispersed by water bath sonication into a substrate buffer (25 mm glycine-NaOH (pH 9.0), containing 5 mm CaCl2, 150 mm NaCl, and 0.3% Triton X-100). The lipid/detergent mixture was boiled for 30 s and chilled on ice immediately to form homogeneous lipid-detergent micelles, which were mixed with an equal volume of microsomes suspended in the same buffer lacking Triton X-100. Enzymatic reaction was initiated by incubating the substrate/enzyme mixture at 37 °C for 20 min. Both enzyme concentration and reaction time were kept in a linear range. The reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of methanol, and the reaction mixture was completely dried on a Savant SpeedVac system (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA). The reaction mixture was hydrolyzed for 30 min at 37 °C with a methanolic KOH solution (0.125 m) to remove phospholipids before long-chain bases were extracted by the Bligh-Dyer method (27). Long-chain bases were derivatized with o-phthaldialdehyde and were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (28).

ESI/MS/MS Analysis

Sphingolipids were determined by ESI/MS/MS performed on a Thermo Finnigan TSQ 7000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, operating in a multiple reaction monitoring positive ionization mode as described previously (29). Briefly, cells were harvested and washed with ice-cold 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, and 5 mm EGTA. Fifty μl of a mixture (1 μm) of internal sphingolipid standards, including C17SPH, C17SPH 1-phosphate, d-e-C16-ceramide (d 17:1/16:0), and d-e-C18-ceramide (d 17:1/18:0), was added to each cell pellet sample before lipid extraction with 4 ml of the ethyl acetate/isopropyl alcohol/water (60:30:10%; v/v) solvent system. After centrifugation, 1 ml of the lipid extract was used for phospholipid (Pi) determination as described previously (30), and the remaining extract was used for ESI/MS/MS. Lipid extracts were dried under a stream of nitrogen gas. For ESI/MS/MS, the dried lipid extract was dissolved in HPLC mobile phase (150 μl, 1 mm ammonium formate in methanol containing 0.2% formic acid). Twenty μl of lipid samples was injected on the Surveyor/TSQ 7000 LC/MS system and gradient-eluted from the BDS Hypersil C8, 150 × 3.2 mm, 3-μm particle size column, with 1.0 mm methanolic ammonium formate, 2 mm aqueous ammonium formate mobile phase system. Peaks corresponding to the target sphingolipid analytes and internal standards were collected and processed using the Xcalibur software system. Quantitative analysis was based on the calibration curves generated by spiking an artificial matrix with the known amounts of the target analyte synthetic standards and an equal amount of internal sphingolipid standards. The target analyte/internal sphingolipid standards peak areas ratios were plotted against analyte concentration, which were normalized to their respective internal sphingolipid standards and compared with the calibration curves, using a linear regression model. Levels of sphingolipids in different cell samples were normalized to Pi.

Statistic Analysis

The Student's t test was applied for statistical analysis using the software GraphPad Prism. Values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. Data represent mean values ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments.

RESULTS

ACER3 Only Uses ULC (Dihydro/Phyto)ceramides as Substrates

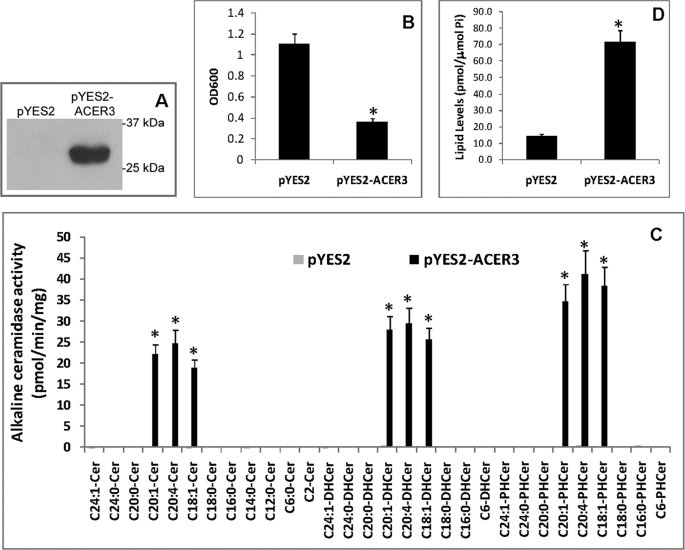

To determine the substrate specificity of ACER3, we investigated what natural substrates ACER3 hydrolyzes in vitro. Because mammalian cells express several ceramidases that may interfere with ACER3 activity assays, we expressed ACER3 in yeast mutant cells (Δypc1Δydc1) that lack endogenous alkaline ceramidase activity because of the deletion of the yeast alkaline ceramidase genes YPC1 and YDC1 (16, 31, 32). We previously generated an ACER3-overexpression yeast strain Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 (16), in which ACER3 expression is directed by the galactose-inducible promoter (Gal1) of the yeast vector pYES2. We also generated the yeast strain Δypc1Δydc1YES2, which contains the empty vector pYES2 and serves as the negative control (16). Δypc1Δydc1YES2 or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells were grown in medium containing galactose before ACER3 expression was determined by Western blot analysis. Because ACER3 was tagged with the epitope tag FLAG, the expression of ACER3 could be minored with an anti-FLAG antibody. Western blot analysis showed that the FLAG-tagged ACER3 was expressed in Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells but not in Δypc1Δydc1YES2 cells (Fig. 1A). It was noted that compared with the growth of Δypc1Δydc1YES2 cells, the growth of Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells was markedly inhibited in the galactose-containing medium (Fig. 1B). To obtain sufficient cell mass for biochemical characterization of ACER3, Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells were grown in glucose-containing medium before being switched to the galactose-containing medium to induce ACER3 expression. Microsomes were isolated from Δypc1Δydc1YES2 or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells and were used for alkaline ceramidase activity assays. When C18:1-, C20:1-, C20:4-ceramides, dihydroceramides, or phytoceramides were used as substrates, Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 microsomes exhibited high alkaline ceramidase activity (Fig. 1C). In contrast, no activity was detected when (dihydro/phyto)ceramides with a medium acyl chain (C12:0 or C14:0), saturated long acyl chain (C16:0, C18:0, C18:1, or C20:0), saturated very long acyl chain (C24:0), or unsaturated very long acyl chain (C24:1) were used as substrates. As expected, Δypc1Δydc1YES2 microsomes exhibited no activity for any of the above mentioned ceramides, dihydroceramides, or phytoceramides. These data suggest that ACER3 uses mono- or poly-ULC phytoceramides, dihydroceramides, and ceramides as substrates.

FIGURE 1.

ACER3 hydrolyzes C18:1-, C20:1-, and C20:4-(phyto/dihydro)ceramides specifically. A, Δypc1Δydc1YES2 (pYES2) or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 (pYES2-ACER3) cells were grown in galactose-containing medium (SD-gal/raf) before microsomes were isolated from these cells. Proteins were solubilized with 1% Triton X-100 from the microsomes and were analyzed by Western blot using anti-FLAG antibody at a 1:1000 dilution. Each lane contained 40 μg of proteins. B, Δypc1Δydc1YES2 or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells were grown to the stationary phase in glucose-containing medium (SD-glu) before being diluted to SD-gal/raf medium. Yeast cells were then grown in SD-gal/raf medium for 16 h before cell density was determined by absorbance at 600 nm (A600). Note that the growth of Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells was significantly inhibited compared with the growth of Δypc1Δydc1YES2 cells. C, Δypc1Δydc1YES2 or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells grown in SD-glu medium were switched to SD-gal/raf medium. At 8 h post-medium switch, yeast cells were harvested, and microsomes were prepared. Microsomal alkaline ceramidase activity was determined at pH 9.0 using various ceramides (Cer), dihydroceramides (DHCer), and phytoceramides (PHCer) as substrates. Each enzymatic reaction contained 150 μm substrate and ∼40 μg of proteins. D, lipids were extracted from Δypc1Δydc1YES2 or Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells grown in SD-gal/raf medium according to the Bligh-Dyer method (27), and PHS levels were determined by HPLC. PHS levels were normalized to total inorganic phosphate (Pi) in lipid extracts. Numerical data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Image datum represents one of three independent experiments with similar results. *, p < 0.05 versus control, n = 3.

Because ACER3 can catalyze the hydrolysis of ULC phytoceramides to generate PHS in vitro, we investigated whether ACER3 overexpression increased the generation of PHS in yeast cells that express high levels of phytoceramides. HPLC analysis showed that Δypc1Δydc1ACER3 cells grown in galactose-containing medium had greater than a 4-fold increase in PHS, compared with Δypc1Δydc1YES2 cells grown in the same medium (Fig. 1D), suggesting that ACER3 overexpression also increases the hydrolysis of phytoceramides in yeast cells.

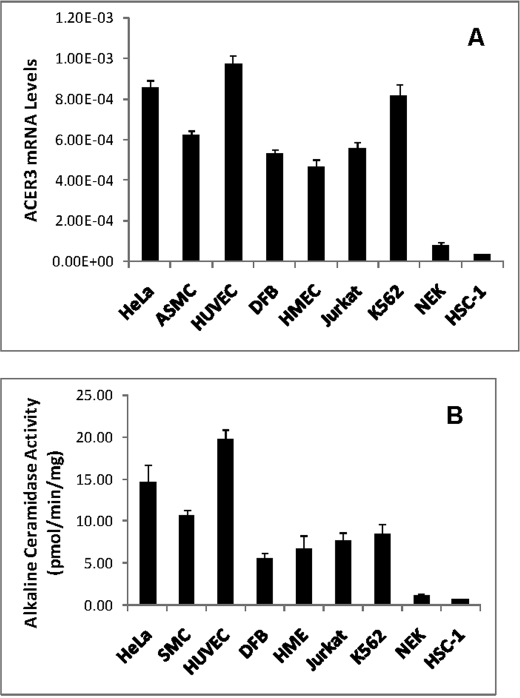

ACER3 Is Highly Expressed in Various Cell Types

We previously demonstrated by Northern blot analysis that ACER3 mRNA transcripts are highly expressed in various tissues (16). To better understand the role of ACER3 in sphingolipid metabolism, we determined its cell type-specific expression. qPCR revealed that ACER3 mRNA transcripts were high in various cell types, including endothelial, epithelial, fibroblast, smooth muscle, and hematopoietic cells (Fig. 2A), suggesting that ACER3 is highly expressed in most cell types. Interestingly, ACER3 is expressed at the lowest levels in normal and malignant epidermal keratinocytes (Fig. 2A). To determine whether its mRNA levels correlate with its activity, we measured alkaline ceramidase activity on its specific synthetic substrate, d-ribo-C12-NBD-phytoceramide, in different cell types. Microsomes were isolated from the indicated cell types and subjected to alkaline ceramidase assays. Microsomal alkaline ceramidase activity of normal or malignant epidermal keratinocytes was much lower than that of the other cell types (Fig. 2B), suggesting a correlation between ACER3 mRNA levels and activity in cells.

FIGURE 2.

ACER3 mRNAs are highly expressed in various cell types. A, total RNA was isolated from different cell types, and ACER3 mRNA levels were determined by qPCR analysis. B, microsomes were isolated from indicated cell types, and alkaline ceramidase activity in the microsomes was measured using d-ribo-C12-NBD-phytoceramide (100 μm) as substrate. ASMC, aortic smooth muscle cells; DFC, dermal fibroblast cells; HMEC, human mammary epithelial cells; and NEK, normal human epidermal keratinocytes. Data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

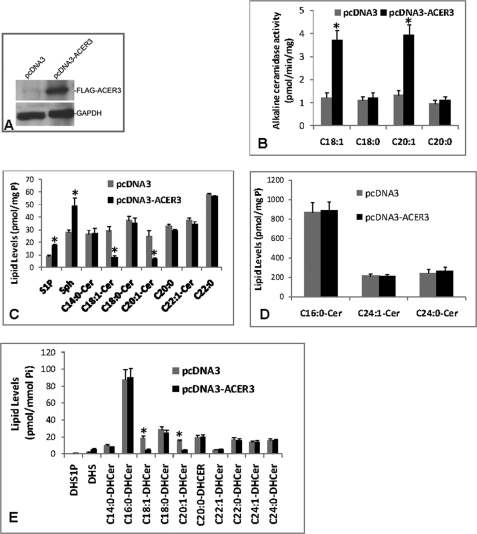

ACER3 Overexpression Decreases ULC Ceramides and Dihydroceramides in Cells

To determine whether ACER3 has cellular ceramidase activity on C18:1- or C20:1-ceramide or dihydroceramide, we evaluated the effects of ACER3 overexpression on cellular ceramides, dihydroceramides, sphingoid bases, and their metabolites. We overexpressed ACER3 in HSC-1 squamous cell carcinoma cells that express the lowest levels of endogenous ACER3 among the cell types that we tested (Fig. 2A). HSC-1 cells were transiently transfected for 72 h with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ACER3. Western blot analysis showed that transfection with pcDNA3-ACER3 but not pcDNA3 induced the expression of FLAG-tagged ACER3 in HSC-1 cells (Fig. 3A). In vitro activity assays showed that compared with transfection with pcDNA3, transfection with pcDNA3-ACER3 increased alkaline ceramidase activity on C18:1- or C20:1-ceramide but not on C18:0- or C20:0-ceramide in HSC-1 cells (Fig. 3B), confirming that ACER3 has activity on unsaturated but not saturated long-chain ceramides. ESI/MS/MS analysis showed that, compared with transfection with pcDNA3, transfection with pcDNA3-ACER3 decreased ULC (C18:1 and C20:1) ceramides or dihydroceramides but increased SPH and S1P in HSC-1 cells without affecting other ceramide or dihydroceramide species (C12:0, C14:0, C16:0, C18:0, C20, C22:0, C22:1, C24:0, C24:1, C26:0, and C26:1) (Fig. 3, C–E). Phytoceramide was undetectable in HSC-1 cells, and ACER3 overexpression failed to alter C18:1- or C20:1-phytoceramide levels in these cells. This suggests that ACER3 also catalyzes the hydrolysis of ULC ceramides or dihydroceramides in cells.

FIGURE 3.

ACER3 overexpression decreases ULC ceramides while increasing SPH and S1P in cells. A, HSC-1 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ACER3 using Effectene according to the manufacturer's instructions. At 72 h post-transfection, microsomes were prepared from cells. Proteins (80 μg) solubilized from a portion of each microsomal preparation were analyzed by Western blot using an anti-FLAG antibody at a 1:1000 dilution. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. B, remaining portion of each microsomal preparation from A was measured for alkaline ceramidase activity at pH 9.0 and with the indicated ceramides (150 μm) as substrates. C–E, HSC-1 cells transected with pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-ACER3 were analyzed by ESI/MS/MS for sphingolipids. Sphingolipid levels were normalized to total phospholipids (Pi). Numerical data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Image datum represents one of two independent experiments with similar results. *, p < 0.05 versus control.

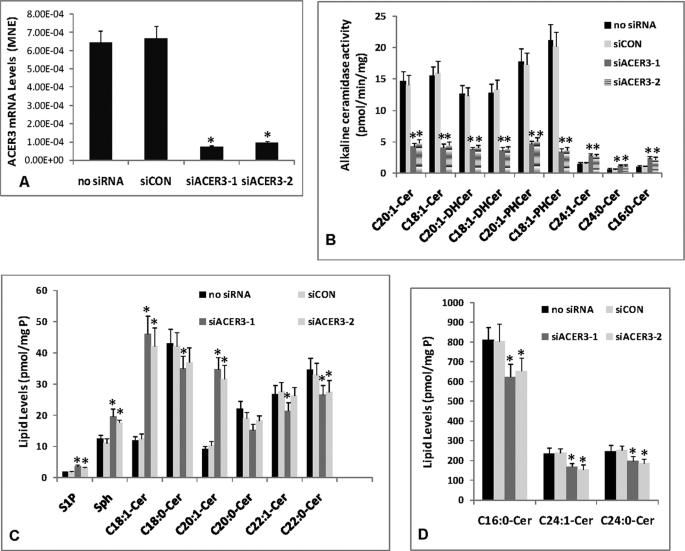

ACER3 Knockdown by RNAi Increases ULC Ceramides and Dihydroceramides in Cells

Overexpression studies suggest that ACER3 can regulate cellular levels of ULC ceramides, SPH, and S1P. To support this observation, we determined the effect of ACER3 knockdown on cellular ceramides, dihydroceramides, sphingoid bases and their phosphates. Because HeLa cervical tumor cells express high levels of both ACER3 mRNAs and activity, we knocked down ACER3 in these cells by RNAi. HeLa cells were transfected with each of two ACER3-specific siRNAs (siACER3-1 and siACER3-2) targeting different regions of the ACER3 coding sequence or a control siRNA (siCON) or treated with buffer only (no siRNA). qPCR analysis demonstrated that compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or ACER3-2 markedly decreased ACER3 mRNA levels in HeLa cells (Fig. 4A). In vitro alkaline ceramidase activity was measured in microsomes isolated from transfected cells. Compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 markedly decreased microsomal alkaline ceramidase activity toward d-ribo-C18:1- or C20:1-phytoceramide, d-e-C18:1- or C20:1-ceramide, and d-e-C18:1- or C20:1-dihydroceramide (Fig. 4B), suggesting that transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 effectively down-regulates the expression of ACER3 in HeLa cells. Interestingly, compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 slightly but significantly increased alkaline ceramidase activity toward C16:0-, C24:0-, and C24:1-ceramide, the major mammalian ceramide species that ACER3 cannot hydrolyze in vitro (Fig. 4B), suggesting that ACER3 knockdown may increase another alkaline ceramidase(s) that uses all the three major ceramides as substrates.

FIGURE 4.

ACER3 knockdown by RNAi increases ULC ceramides in cells. A–D, HeLa cells at a 50% confluence were transfected with 5 nm siCON, siACER3-1, or siACER3-2, or with buffer only (no siRNA). At 48 h post-siRNA transfection, cells were harvested for qPCR analysis of ACER3 mRNA levels (A), alkaline ceramidase activity assays (B), or ESI/MS/MS analyses of sphingolipids (C and D). Data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 versus the control siCON or no siRNA. MNE, mean normalized expression.

ESI/MS/MS analysis revealed that, compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 increased C18:1- or C20:1-ceramide or dihydroceramide (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 slightly but significantly increased SPH and S1P (Fig. 4C) while decreasing other ceramide species (C14:0-, C16:0-, C18:0-, C20:0-, C24:0-, and C24:1-ceramide) (Fig. 4, C and D). These results suggest that RNAi-mediated ACER3 knockdown mainly increases ULC ceramides with slight but significant alterations in non-ULC ceramide species, SPH, and S1P in cells.

ACER3 Knockdown Up-regulates ACER2

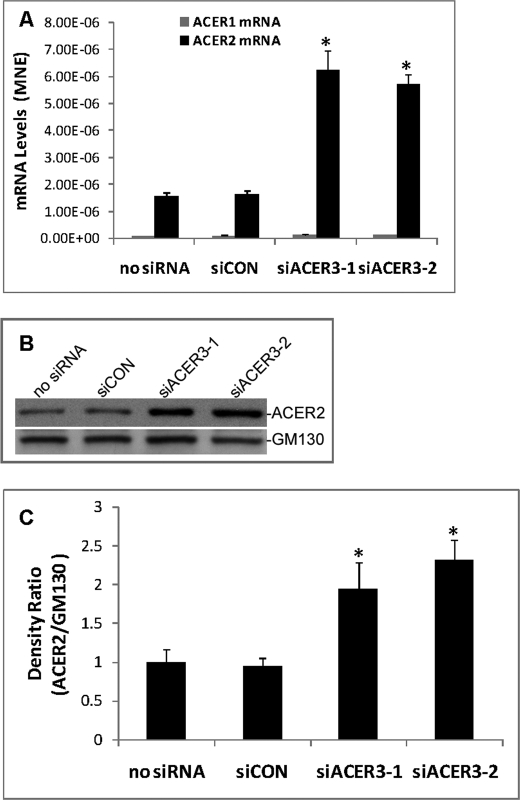

ACER3 knockdown increased alkaline ceramidase activity on the major ceramide species (C16:0, C24:0, and C24:1) while decreasing the cellular levels of these ceramide species, none of which ACER3 can hydrolyze. This prompted us to investigate whether ACER3 knockdown increases the expression of ACER2, whose up-regulation was shown to decrease most ceramide species in HeLa cells (15). qPCR analyses showed that compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 caused greater than a 3-fold increase in mRNA of ACER2 in HeLa cells without affecting mRNA of ACER1, another alkaline ceramidase (Fig. 5A). Western blot revealed that transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 also increased protein levels of ACER2 (Fig. 5, B and C). These results suggest that ACER3 knockdown indeed up-regulates the expression of ACER2 in HeLa cells.

FIGURE 5.

ACER3 knockdown up-regulates ACER2. A–C, HeLa cells were transfected with siCON, siACER3-1, or siACER3-2 or siACER3 at 5 nm or with no siRNA for 48 h before qPCR analysis for ACER1 or ACER2 mRNA levels (A), Western blot analysis for ACER2 and β-actin (B), or densitometry for ACER2 and β-actin (C) was performed. Densitometry was performed on a ChemiImager 4400 system (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). The ACER2/β-actin density ratio in cells transfected with no siRNA was arbitrarily set as 1, and the relative ACER2/β-actin density ratios were accordingly computed in cells transfected with each of other different siRNAs. Data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Image datum represents one of three independent experiments with similar results. *, p < 0.05 versus the controls (siCON or no siRNA). MNE, mean normalized expression.

ACER3 Down-regulation Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Up-regulates p21CIP1/WAF1

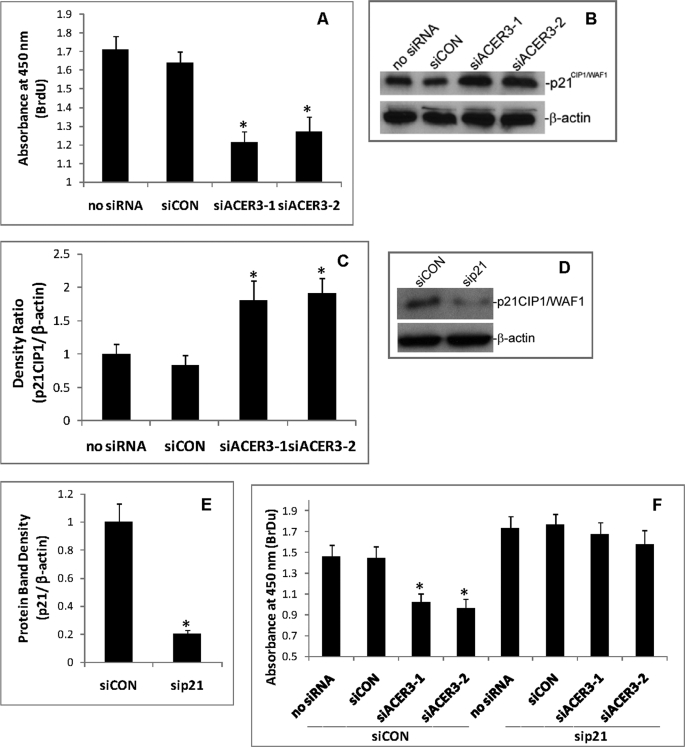

Because ACER3 knockdown altered the cellular levels of sphingolipids that are implicated in cell growth regulation, we determined the effect of ACER3 knockdown on cell proliferation. HeLa cells were transfected with siCON, siACER3-1, or siACER3-2 or with no siRNA for 72 h before cell proliferation was determined. qPCR confirmed that compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 knocked down ACER3 expression (data not shown). Cell proliferation assays revealed that, compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or ACER3-2 significantly decreased BrdUrd incorporation into nuclei of HeLa cells (Fig. 6A), suggesting that ACER3 knockdown inhibits the proliferation of HeLa cells.

FIGURE 6.

ACER3 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation. A, HeLa cells were transfected with siCON, siACER3-1, siACER3-2, or with no siRNA as described in Fig. 5 for 72 h before cell proliferation ELISA was performed. B and C, HeLa cells were transfected with each of the indicated siRNAs for 48 h before p21CIP1/WAF1 levels were analyzed by Western blot (B) and quantified by densitometry (C). D and E, HeLa cells were transfected with siCON (5 nm) or sip21 (5 nm), a sip21CIP1/WAF1-specific siRNA for 48 h before the content of p21CIP1/WAF1 was analyzed by Western blot with anti-p21CIP1/WAF1 antibody (D), followed by densitometry (E). F, HeLa cells were transfected with siCON plus siACER3-1, siCON plus siACER3-2, siCON plus buffer only (no siRNA), sip21 plus siCON, sip21 plus siACER3-1, sip21 plus siACER3, or sip21 plus buffer only (no siRNA) at 5 nm each. At 72 h post-siRNA transfection, cells were subjected to cell proliferation ELISA. Numerical data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Image datum represents one of three independent experiments with similar results. *, p < 0.05 versus the control (siCON or no siRNA).

Treatment with short-chain ceramide or bacterial sphingomyelinase that releases free ceramides from sphingomyelins has been shown to increase the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21CIP1/WAF1 (33–35), a key negative regulator of cell proliferation. These observations prompted us to investigate whether ACER3 knockdown also up-regulates p21CIP1/WAF1 in HeLa cells. In line with the previous results, Western blot revealed that, compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 increased p21CIP1/WAF1 in HeLa cells (Fig. 6, B and C), suggesting that ACER3 knockdown up-regulates p21CIP1/WAF1 expression.

To determine whether p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation is indeed associated with cell proliferation inhibition by ACER3 knockdown, we investigated whether inhibiting p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation by a p21CIP1/WAF1-specific siRNA (sip21) attenuates the inhibitory effect of ACER3 knockdown on cell proliferation. Western blot analysis confirmed the effectiveness of sip21 in knocking down p21CIP1/WAF1 in HeLa cells (Fig. 6, D and E). HeLa cells were transfected with siCON plus no siRNA, siCON plus siCON, siCON plus siACER3-1, siCON plus siACER3-2, sip21 plus no siRNA, sip21 plus siCON, sip21 plus siACER3-1, or sip21 plus siACER3-2 before cell proliferation was determined. Compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 inhibited the proliferation of HeLa cells transfected with siCON but not the proliferation of HeLa cells transfected with sip21 (Fig. 6F), suggesting that ACER3 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation because of p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation.

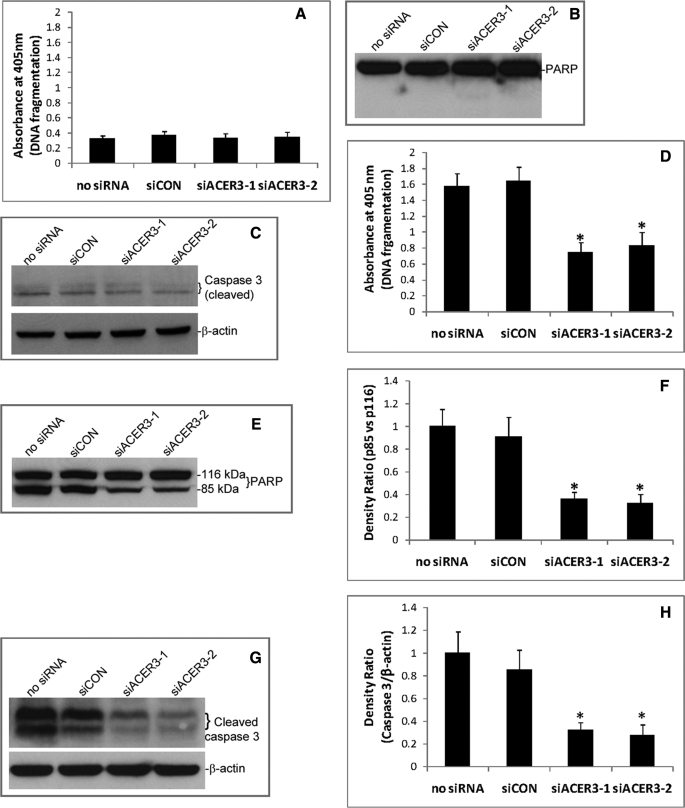

ACER3 Down-regulation Inhibits Apoptosis in Response to Serum Deprivation

Because ACER3 knockdown altered the cellular levels of sphingolipids that are implicated in cell apoptosis, we measured the effect of ACER3 knockdown on the apoptosis of HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with siCON, siACER3-1, or siACER3-2 or with no siRNA before cell apoptosis was assayed by cell death detection ELISA to measure mono- or oligonucleosomes released from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, i.e. DNA fragmentation, a hallmark of apoptosis. Compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 did not increase DNA fragmentation in HeLa cells in regular medium (Fig. 7A). Western blot revealed that transfection with any of the above siRNAs neither induced PARP cleavage, another hallmark of apoptosis (Fig. 7B), nor increased the cleaved (active) form of caspase 3 in HeLa cells in regular medium (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that ACER3 knockdown does not induce apoptosis of HeLa cells under normal culture conditions.

FIGURE 7.

ACER3 knockdown inhibits apoptosis in response to serum deprivation. A–C, HeLa cells were transfected with indicated siRNAs as described in Fig. 5 in regular medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 72 h before they were subjected to cell death detection ELISA (A), Western blot analysis for PARP cleavage (B), or caspase 3 cleavage (C). D–F, HeLa cells were transfected with indicated siRNAs for 24 h before they were switched to serum-free medium. At 48 h post-serum deprivation, the cells were subjected to cell death detection ELISA (D), Western blot analysis for PARP cleavage (E), densitometry of PARP (F), Western blot analysis for caspase 3 cleavage (G), and densitometry of caspase 3 (H). Numerical data represent mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Image data represent one of three independent experiments with similar results. *, p < 0.05 versus the control (siCON or no siRNA).

Because ceramides have been shown to mediate cell apoptosis in response to various stress stimuli, we determined whether ACER3 knockdown had any effect on cell apoptosis in response to a stimulus that induces the generation of ceramides, such as serum deprivation (36). HeLa cells transfected with different siRNAs were subjected to serum deprivation. Compared with transfection with no siRNA or with siCON, transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 significantly inhibited serum deprivation-induced DNA fragmentation (Fig. 7D), PARP cleavage (Fig. 7, E and F), or caspase 3 activation (Fig. 7, G and H). These results suggest that RNAi-mediated ACER3 knockdown inhibits cell apoptosis in response to serum deprivation.

DISCUSSION

ACER3 was the first mammalian alkaline ceramidase to be cloned by our group (16). Because of the unique substrate specificity of ACER3, our attempt to identify its natural substrates was initially fruitless. In this study, we not only successfully elucidated the substrate specificity of ACER3 but also defined its roles in the metabolism of sphingolipids and cellular responses. There are several major findings of this study. First, we found that ACER3 only uses monounsaturated (C18:1 and C20:1) or polyunsaturated (C20:4) long-chain ceramides, dihydroceramides, or phytoceramides as in vitro substrates. Second, we identified ACER3 as the first mammalian alkaline ceramidase that catalyzes the hydrolysis of natural phytoceramides to generate PHS in (yeast) cells. Finally, we revealed that ACER3 has the ability to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis by controlling the hydrolysis of ULC ceramides.

ACER3 differs from other human ceramidases by having unique substrate specificity. Unlike other human ceramidases that use at least one of the major mammalian ceramide species (C16-, C24:0-, and C24:1-ceramide) as substrate(s), ACER3 only catalyzes the hydrolysis of the minor ULC ceramide species (d-e-C18:1, C20:1, or C20:4-ceramide). Distinct from the other ceramidases that prefer SPH-containing ceramides over dihydroceramides or phytoceramides as substrates, ACER3 catalyzes the hydrolysis of ULC dihydroceramides or phytoceramides as efficiently as their ceramide counterparts. These results suggest that the composition of the ceramide acyl chain is more critical for ACER3 activity than the structure of the sphingoid base moiety. This indicates that ACER3 is a unique ceramidase in terms of substrate specificity.

Different cell types have distinct compositions of ceramides differing in both the length and unsaturation degree of the acyl chain. Ceramides are synthesized through the action of (dihydro)ceramide synthases (CERSs) (37, 38). To date, six human CERS isozymes have been cloned, and each CERS catalyzes the formation of ceramides with specific acyl chain lengths. The specificity of CERSs for the degree of unsaturation of acyl chains remains unclear, although CERS5/LASS5 was shown to be capable of synthesizing C18:1-ceramide (39). As mentioned earlier, there are also multiple human ceramidases, and each catalyzes the hydrolysis of ceramide species with certain acyl chain lengths and unsaturation degrees. Therefore, the composition of ceramide species in a particular cell type or tissue mainly is determined by the expression levels of both CERS and ceramidase isozymes.

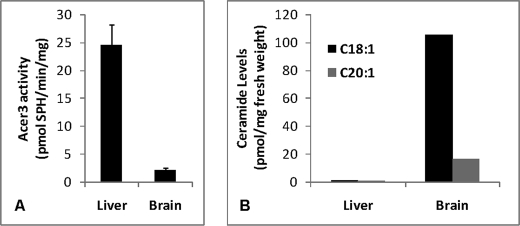

Consistent with its in vitro substrate specificity, ACER3 plays a specific role in controlling cellular ULC ceramides and dihydroceramides. This is supported by two lines of direct evidence. First, ACER3 overexpression decreased ULC ceramides but not other ceramide species in HSC-1 cells. Second, ACER3 knockdown significantly increased the cellular levels of C18:1- and C20:1-ceramides. Furthermore, the specific role of ACER3 in regulating ULC ceramide levels is supported by an inverse correlation between ACER3 activity and levels of ULC ceramides in cells or tissues. C18:1- and C20:1-ceramides are much greater in HSC-1 cells than in HeLa cells, although the opposite is true with ACER3 activity. There is also an inverse correlation between the mouse alkaline ceramidase 3 activity and the levels of ULC ceramides in mouse liver and brain (Fig. 8).

FIGURE 8.

ULC ceramides are abundant in the mouse brain with low ACER3 activity. A 2-month old male mouse was sacrificed, and liver and brain tissues were resected. The same fresh weight of liver and brain tissues were homogenized in 25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing EDTA (5 mm), EGTA (5 mm), and NaCl (150 mm). Tissue homogenates of each tissue were divided into 4 aliquots with the same volume. Two aliquots were assayed for ACER3 activity on NBD-C12-phytoceramide (A), and the remaining aliquots were analyzed by ESI/MS/MS for the of C18:0- and C20:1-ceramides (B).

In addition to ULC ceramides, ACER3 also plays a role in regulating cellular ULC dihydroceramides because ACER3 overexpression decreased, whereas its knockdown increased, cellular C18:1- and C20:1-dihydroceramides. Although we showed that ACER3 in vitro hydrolyzed ULC phytoceramides efficiently, ACER3 knockdown in HeLa cells failed to increase their cellular levels (data not shown), suggesting that phytoceramides may not be synthesized in this cell type or may be too low to detect. In other human cell types that do synthesize phytoceramides, ACER3 knockdown is expected to increase cellular levels of ULC phytoceramides because we showed that ACER3 could hydrolyze phytoceramides to generate PHS in (yeast) cells. Based on the aforementioned observations, we concluded that ACER3 plays a key role in regulating the homeostasis of ULC (phyto/dihydro)ceramides in cells or tissues.

It is noteworthy that d-e-C20:4-ceramide is also a substrate of ACER3, although this polyunsaturated long-chain ceramide is undetectable in HeLa or HSC-1 cells. In fact, to date, the existence of polyunsaturated long-chain ceramides or dihydroceramides has not been reported in any mammalian cell types or tissues, although polyunsaturated very long-chain ceramides, such as C28:4-ceramide, have been detected in mouse or rat testicular tissues (40). The absence of an arachidonoyl group in sphingolipids suggests that either none of CERS isozymes use arachidonoyl-CoA as substrate or ACER3 efficiently eradicates C20:4-ceramide from cells. The latter case is very likely because we previously demonstrated that ACER3 is highly expressed in most tissues (16). The physiological relevance for ACER3 to keep ULC and polyunsaturated long-chain ceramides at the lowest levels in cells and tissues remains unclear. Because complex sphingolipids in lipid rafts of the plasma membrane mainly have saturated acyl chains, the presence of mono- and polyunsaturated long acyl chains may have an adverse effect on the physiochemical properties of lipid rafts (41). Therefore, high ACER3 activity may be important for the integrity and function of lipid rafts by preventing polyunsaturated fatty acids from being incorporated into sphingolipids in lipid rafts. This possibility is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Interestingly, although ACER3 does not use saturated long-chain ceramides or very long-chain ceramides, ACER3 knockdown slightly but significantly deceased their cellular levels while increasing both SPH and S1P. These unexpected effects may be caused by up-regulation of ACER2 because ACER3 knockdown up-regulated the expression of ACER2, another alkaline ceramidase whose up-regulation was shown to decrease most ceramide species while increasing both SPH and S1P (15). We demonstrated that ACER2 in vitro catalyzes the hydrolysis of most mammalian ceramides, including ULC ceramides.4 ACER2 up-regulation did not affect the ACER3 knockdown-induced increase in cellular ULC ceramides, suggesting that ACER2 up-regulation cannot compensate for the ability of ACER3 to hydrolyze ULC ceramides in cells. This is probably because cells express much more ACER3 than those of ACER2. ACER2 up-regulation can compensate for the ability of ACER3 to generate both SPH and S1P in cells. This is because the substrates of ACER2 are much more abundant than the substrates of ACER3. The physiological relevance of ACER2 up-regulation may be to maintain SPH and S1P at constant levels in cells where ACER3 is down-regulated or inhibited. Therefore, ACER3 and ACER2 may have a complementary role in regulating the generation of SPH and S1P in cells.

Compared with transfection with siCON or with no siRNA, transfection with an ACER3-specific siRNA, siACER3-1 or siACER3-2, not only decreased ACER3 expression but also increased ACER2 expression, so the biological effects of siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 may be caused by ACER3 down-regulation, ACER2 up-regulation, or both. We demonstrated that transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 inhibited the proliferation of HeLa cells. Because we previously showed that a moderate increase in ACER2 expression does not affect the proliferation of HeLa cells in regular serum-containing medium, the inhibitory effect of siACER3-1 or ACER3-2 on cell proliferation may be caused by ACER3 knockdown but not by ACER2 up-regulation. Therefore, the inhibitory effect of ACER3 knockdown on cell proliferation is probably due to an accumulation of ULC ceramides and their derivatives. This idea is in line with a general view that ceramides are anti-proliferative bioactive lipids.

p21CIP1/WAF1 up-regulation has been suggested to be a mechanism by which synthetic short-chain ceramide or endogenous ceramide generated by treatment with bacterial sphingomyelinase induces cell growth arrest (33–35). In agreement with these studies, we showed that an increase in endogenous ULC ceramides also up-regulated p21CIP1/WAF1. Because p21CIP1/WAF1 has been implicated in growth arrest in various tumor cell types, its up-regulation appears to be important for cell growth arrest induced by increased ULC ceramides. This is supported by the finding that RNAi-mediated knockdown of p21CIP1/WAF1 significantly attenuated the inhibitory effect of ACER3 knockdown on cell proliferation. The mechanism by which ULC ceramides up-regulate p21CIP1/WAF1 is under investigation.

Transfection with siACER3-1 or siACER3-2 protected cells from apoptosis in response to serum deprivation. The protective effect of siACER3 could also be due to ACER3 down-regulation, ACER2 up-regulation, or both. If ACER3 knockdown is responsible, increased ULC ceramides may have a protective role in apoptosis. This is contradictory to a general view that ceramides are pro-apoptotic bioactive lipids. Interestingly, although the synthetic d-e-C6-ceramide has been shown to induce the apoptosis of various cell types, Plummer et al. (42) demonstrated that treatment with C6-ceramide inhibits apoptosis of sympathetic neurons in response to nerve growth factor deprivation. C6-ceramide was shown to increase endogenous long-chain ceramides through a deacylation-reacylation recycling pathway (43). Because ULC ceramides are abundant in brain tissue (Fig. 8), treatment with exogenous C6-ceramide may preferentially increase ULC ceramides in sympathetic neurons, thus enhancing cell survival against nerve growth factor deprivation. We previously demonstrated that ACER2 up-regulation protects HeLa cells from apoptosis in response to serum deprivation by increasing the generation of S1P, a serum component that has been shown to potently inhibit the apoptosis of cells grown in serum-free medium (15). This supports the notion that ACER2 up-regulation and S1P increase may also be responsible for the anti-apoptotic effect of siACER3-1 or siACER3-2.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that ACER3 is highly expressed in various cell types and has distinct substrate specificity from other ceramidases. Its high expression plays a role in cell proliferation by minimizing the cellular levels of ULC ceramides, which are otherwise anti-proliferative. ACER3 also has the ability to control the generation of SPH and S1P in cells. Loss of this ability can be compensated by up-regulation of ACER2, another alkaline ceramidase, suggesting that alkaline ceramidases have a complementary role in regulating the generation of SPH and S1P in cells.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Jennifer Schnellmann for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P20RR017677 (to C. M.), R01CA104834 (to C. M.), and R01GM062887 (to L. M. O.). This work was also supported by a Veterans Affairs Merit award (to L. M. O.).

Sun, W., Jin, J., Xu, R., Hu, W., Szulc, Z. M., Bielawski, J., Obeid, L. M., and Mao, C. (January 20, 2010) J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M109.069203.

- SPH

- sphingosine

- S1P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- RNAi

- RNA interference

- ULC

- unsaturated long chain

- PARP

- poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- BrdUrd

- bromodeoxyuridine

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- ESI/MS/MS

- electrospray ionization/tandem mass spectrometry

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- NC

- nitrocellulose

- PHS

- phytosphingosine

- NBD

- 12-(N-methyl-N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl))

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- CERS

- (dihydro)ceramide synthase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mao C., Obeid L. M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1781, 424–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanna A. N., Berthiaume L. G., Kikuchi Y., Begg D., Bourgoin S., Brindley D. N. (2001) Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3618–3630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charles A. G., Han T. Y., Liu Y. Y., Hansen N., Giuliano A. E., Cabot M. C. (2001) Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 47, 444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magnoni C., Euclidi E., Benassi L., Bertazzoni G., Cossarizza A., Seidenari S., Giannetti A. (2002) Toxicol. In Vitro 16, 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaffrézou J. P., Bruno A. P., Moisand A., Levade T., Laurent G. (2001) FASEB J. 15, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuvillier O. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1585, 153–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuvillier O., Levade T. (2003) Pharmacol. Res. 47, 439–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kohama T., Olivera A., Edsall L., Nagiec M. M., Dickson R., Spiegel S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23722–23728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu H., Sugiura M., Nava V. E., Edsall L. C., Kono K., Poulton S., Milstien S., Kohama T., Spiegel S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 19513–19520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez S. E., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2007) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.el Bawab S., Mao C., Obeid L. M., Hannun Y. A. (2002) Subcell. Biochem. 36, 187–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koch J., Gärtner S., Li C. M., Quintern L. E., Bernardo K., Levran O., Schnabel D., Desnick R. J., Schuchman E. H., Sandhoff K. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 33110–33115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Bawab S., Roddy P., Qian T., Bielawska A., Lemasters J. J., Hannun Y. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21508–21513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun W., Xu R., Hu W., Jin J., Crellin H. A., Bielawski J., Szulc Z. M., Thiers B. H., Obeid L. M., Mao C. (2008) J. Invest. Dermatol. 128, 389–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu R., Jin J., Hu W., Sun W., Bielawski J., Szulc Z., Taha T., Obeid L. M., Mao C. (2006) FASEB J. 20, 1813–1825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mao C., Xu R., Szulc Z. M., Bielawska A., Galadari S. H., Obeid L. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 26577–26588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momoi T., Ben-Yoseph Y., Nadler H. L. (1982) Biochem. J. 205, 419–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang Y. H., Tani M., Nakagawa T., Okino N., Ito M. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Bawab S., Bielawska A., Hannun Y. A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 27948–27955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen W. W., Decker G. L. (1982) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 718, 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ehlert K., Frosch M., Fehse N., Zander A., Roth J., Vormoor J. (2007) Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 5, 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holman D. H., Turner L. S., El-Zawahry A., Elojeimy S., Liu X., Bielawski J., Szulc Z. M., Norris K., Zeidan Y. H., Hannun Y. A., Bielawska A., Norris J. S. (2008) Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 61, 231–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu B. X., Zeidan Y. H., Hannun Y. A. (2009) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1791, 730–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Usta J., El Bawab S., Roddy P., Szulc Z. M., Yusuf, Hannun A., Bielawska A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 9657–9668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao C., Xu R., Szulc Z. M., Bielawski J., Becker K. P., Bielawska A., Galadari S. H., Hu W., Obeid L. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31184–31191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller P. Y., Janovjak H., Miserez A. R., Dobbie Z. (2002) Biotechniques 32, 1372–1379 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959) Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37, 911–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merrill A. H., Jr., Wang E., Mullins R. E., Jamison W. C., Nimkar S., Liotta D. C. (1988) Anal. Biochem. 171, 373–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bielawski J., Szulc Z. M., Hannun Y. A., Bielawska A. (2006) Methods 39, 82–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Veldhoven P. P., Bell R. M. (1988) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 959, 185–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao C., Xu R., Bielawska A., Szulc Z. M., Obeid L. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31369–31378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mao C., Xu R., Bielawska A., Obeid L. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6876–6884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips D. C., Hunt J. T., Moneypenny C. G., Maclean K. H., McKenzie P. P., Harris L. C., Houghton J. A. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 1780–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J., Lv X. W., Shi J. P., Hu X. S. (2007) World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 1129–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alesse E., Zazzeroni F., Angelucci A., Giannini G., Di Marcotullio L., Gulino A. (1998) Cell Death Differ. 5, 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colombaioni L., Frago L. M., Varela-Nieto I., Pesi R., Garcia-Gil M. (2002) Neurochem. Int. 40, 327–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng W., Kollmeyer J., Symolon H., Momin A., Munter E., Wang E., Kelly S., Allegood J. C., Liu Y., Peng Q., Ramaraju H., Sullards M. C., Cabot M., Merrill A. H., Jr. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758, 1864–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pewzner-Jung Y., Ben-Dor S., Futerman A. H. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 25001–25005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mizutani Y., Kihara A., Igarashi Y. (2005) Biochem. J. 390, 263–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furland N. E., Zanetti S. R., Oresti G. M., Maldonado E. N., Aveldaño M. I. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18141–18150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wassall S. R., Stillwell W. (2008) Chem. Phys. Lipids 153, 57–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plummer G., Perreault K. R., Holmes C. F., Posse De Chaves E. I. (2005) Biochem. J. 385, 685–693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogretmen B., Pettus B. J., Rossi M. J., Wood R., Usta J., Szulc Z., Bielawska A., Obeid L. M., Hannun Y. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12960–12969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]