Abstract

The role of aldosterone has been implicated in the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases. The biological actions of aldosterone are mediated through mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). Nuclear receptor-mediated gene expression is regulated by dynamic and coordinated recruitment of coactivators and corepressors. To identify new coregulators of the MR, full-length MR was used as bait in yeast two-hybrid screening. We isolated NF-YC, one of the subunits of heterotrimeric transcription factor NF-Y. Specific interaction between MR and NF-YC was confirmed by yeast two-hybrid, mammalian two-hybrid, coimmunoprecipitation assays, and fluorescence subcellular imaging. Transient transfection experiments in COS-7 cells demonstrated that NF-YC repressed MR transactivation in a hormone-sensitive manner. Moreover, reduction of NF-YC protein levels by small interfering RNA potentiated hormonal activation of endogenous target genes in stably MR-expressing cells, indicating that NF-YC functions as an agonist-dependent MR corepressor. The corepressor function of NF-YC is selective for MR, because overexpression of NF-YC did not affect transcriptional activity mediated by androgen, progesterone, or glucocorticoid receptors. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments showed that endogenous MR and steroid receptor coactivator-1 were recruited to an endogenous ENaC gene promoter in a largely aldosterone-dependent manner, and endogenous NF-YC was sequentially recruited to the same element. Immunohistochemistry showed that endogenous MR and NF-YC were colocalized within the mouse kidney. Although aldosterone induces interaction of the N and C termini of MR, NF-YC inhibited the N/C interaction. These findings indicate that NF-YC functions as a new corepressor of agonist-bound MR via alteration of aldosterone-induced MR conformation.

Keywords: Gene/Transcription, Histones/Deacetylase, Hormones/Steroid, Receptors/Nuclear, Transcription/Coactivators, Transcription/Repressor, NF-YC, Aldosterone, Corepressor, Mineralocorticoid Receptor

Introduction

Aldosterone, through binding to mineralocorticoid receptor (MR, NR3C2),2 promotes renal sodium reabsorption and potassium secretion in epithelial cells, most notably in the kidney and colon. Aldosterone also plays important roles in non-epithelial cells, such as cardiac myocytes and vascular walls (1, 2). Primary aldosteronism, which is defined as hypertension, high plasma aldosterone concentration, and suppressed plasma renin activity level, reveals higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases than essential hypertension. Recent data also indicate that inappropriate levels of aldosterone, in the presence of moderate to high salt intake, result in significant tissue damage in non-epithelial cells, such as endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, and myocardial fibrosis through MR activation. Two clinical trials, the randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (3) and Eplerenone Post-acute Myocardial Infarction Heart Failure Efficacy and Survival Study (4), shed new light on MR as an important pathogenic mediator of cardiac and vascular remodeling, because treatment with MR antagonist spironolactone or eplerenone was effective in significantly reducing the morbidity and mortality of patients with congestive heart failure. However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of the successful treatment with MR antagonist remain to be elucidated.

Over the past decade, it has become clear that an increasing number of nuclear receptor coregulators is required to either enhance or repress nuclear receptor-mediated transactivation of target genes. Nuclear receptor coregulators are composed of both coactivators and corepressors and are defined as cellular factors, which interact with nuclear receptors to potentiate or attenuate transactivation (5–12). A subset of coregulators may contribute to tissue and ligand specificity to MR-mediated responses due to their structural and functional diversity. Unexpectedly, among over 300 coregulators, the number of MR-interacting coregulators identified to date is very limited (9, 13). MR ligand-binding domain interacts strongly with only a few specific coactivator peptides, such as p160 family coactivators, steroid receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1), SRC-2, and SRC-3, activating signal cointegrator 2, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α in the presence of aldosterone (9, 13–15). In addition, several coactivators, such as RHA (16), ELL (12), and Ubc9 (17), interact with the MR N-terminal AF-1 domain. It is now recognized that coregulators play an important role in a range of diseases, including cancer, inflammatory disease, and metabolic disorders.

We have previously reported that Ubc9 functions as a coactivator of MR by forming a complex with the MR N terminus and SRC-1, independently of its E2 SUMO-1-conjugating enzyme activity (17). In this study, we have identified NF-YC as a novel molecular partner of MR using a yeast two-hybrid screening with a full-length MR. NF-Y is a ubiquitous heterotrimeric transcription factor, composed of NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC subunits, which recognizes a CCAAT box motif found in many eukaryotic promoter and enhancer elements (18–22). We describe a new function of NF-YC as a corepressor of agonist-bound MR, the function of which is independent of histone deacetylase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Constructs

Several MR fragments, such as MR-(1–984), MR-(1–670), and MR-(671–984), were subcloned into pGBKT7, pcDNA3.1/His, and pDsRed vectors as described previously (17). MR-(602–984) was subcloned into pGBKT7. In detail, MR fragment was first obtained by PCR amplification with primers containing oligonucleotide linkers of restriction enzyme sites (XmaI-SalI), followed by TA cloning into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The pCRII-TOPO-MR-(602–984) construct was then digested with XmaI-SalI and subcloned into pGBKT7 yeast expression vector. pGADT7-NF-YC was cloned as an MR interacting protein by using a yeast two-hybrid system. pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC was constructed by inserting the 2.1-kb EcoRI fragment of pGADT7-NF-YC from the 3.5-kb original cDNA into the EcoRI site of pcDNA3.1/His vector (Invitrogen). pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC-(1–115) was constructed by using DNA Blunting Kit (TaKaRa) after excluding the small ClaI-XhoI fragment of pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC. pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC-(116–335) was constructed by using the DNA Blunting Kit (TaKaRa) after excluding the small BamHI-ClaI fragment of pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC. Gal4-DBD-NF-YC mammalian expression plasmid of Gal4-DBD-NF-YC (pM-NF-YC) was constructed by inserting the EcoRI fragment of pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC into the EcoRI site of pM vector. pEGFP-NF-YC was constructed by inserting the EcoRI fragment of pGADT7-NF-YC into the EcoRI site of pEGFP vector. DNA sequencing of all the constructs was confirmed by ABI PRISM dye terminator cycle sequencing analysis (Amersham Biosciences). 3×MRE-Elb-Luc was a generous gift from Dr. Bert W. O'Malley (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston). pRShMR was a generous gift from Dr. Ronald M. Evans (The Salk Institute for Biological Studies). pG5-Luc, pVP16-MR-(1–597), and pM-MR (672–984) encoding Gal4-DBD-MR (672–984) for mammalian two-hybrid assays were generous gifts from Dr. Peter J. Fuller (Prince Henry's Institute of Medical Research). pSG5-NF-YC was a generous gift from Dr. Roberto Mantovani. pCMV-hGRα was a generous gift from Dr. John A. Cidlowski (National Institutes of Health). pcDNA3-hAR and pcDNA3-hPRB were generous gifts from Dr. Shigeaki Kato (University of Tokyo).

Antibodies

Goat anti-human NF-YC (C-19) antibody, and rabbit anti-human NF-YC (H-120) antibody, goat anti-human MR (N-17) antibody, goat anti-human SRC-1 (M-341), and normal goat IgG were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Rabbit anti-human NF-YA antibody and rabbit anti-human NF-YB antibody were obtained from Abcam.

Generation of Human MR-expressing Cell Line, 293-MR

Human-293F embryonic kidney cells and transformants were routinely maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, UT). 293-MR cells stably expressing human MR have been established and described in detail previously (17).

Cloning of NF-YC by a Yeast Two-hybrid System

Yeast two-hybrid screening was conducted with a MACHMAKER Two-Hybrid System 3 Kit (Clontech) and full-length human MR (amino acids 1–984) as bait. A human heart cDNA library was prepared as follows. Human heart poly(A) RNA was obtained from Clontech Laboratories, and cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription of the mRNA with an oligo(dT)18 linker. We then transformed Escherichia coli competent cells with cDNAs by electroporation, and ligated the cDNAs into the pGADT7 vector. Yeast strain AH109 containing pGBKT7-hMR-(1–984) was transformed with a human heart cDNA library in pGADT7 (Clontech) and plated on synthetic complete medium lacking tryptophan, adenine, leucine, and histidine (23). His+ and Ade+ colonies exhibiting β-galactosidase activity by filter lift assay were further characterized according to the manufacturer's protocol (Clontech). β-Galactosidase activity was determined with chlorophenol red β-d-galactopyranoside as described previously (24). To recover the library plasmids, total DNA from the yeast was isolated with a Zymoprep Yeast Plasmid Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Orange, CA) and used to transform E. coli (HB101) in the presence of ampicillin. To ensure that the correct cDNAs were identified, the library plasmids isolated were transformed into Y187 containing pGBKT7-hMR-(1–984), and β-galactosidase activity was determined. The specificity of the interaction of NF-YC, one of the five positive clones, with hMR was determined by mating with Y187, which contains pGBKT7-lamin (Clontech). The β-galactosidase activity of these diploids was examined by the filter lift and chlorophenol red β-d-galactopyranoside methods. The sequence of the NF-YC clone was identical to the GenBankTM-submitted sequence of NF-YC, respectively. The yeast two-hybrid system was also used to determine protein-protein interaction of NF-YC and deletion mutants of hMR.

Mammalian Cell Culture, Transient Transfections, and Luciferase Assays

COS-7 cells and HEK293 cells were routinely maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Protocols of transient transfections and luciferase assays were described elsewhere.

Western Blots and Coimmunoprecipitation Assays

Whole cell lysates were prepared by homogenization in buffer composed of 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mm EDTA, and 2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Protocols of Western blots and coimmunoprecipitation assays were described elsewhere (17, 25, 26).

Fluorescence Imaging

HEK-293 cells were transient transfected with expression vectors of pEGFP-NF-YC and pDsRed-MR. Live cell microscopy of GFP fusion and DsRed fusion proteins was performed on a confocal microscope (Axiovert 100M, Carl Zeiss Co., Ltd.).

RNA Interference

COS-7 cells were transfected with siRNAs, and luciferase assays were performed as described previously (17). COS-7 cells were plated into 24-well plates, grown until reaching 30–50% confluence, and transfected with 10 pmol/well of NF-YC specific siRNA (SC37733, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or Silencer Negative Control siRNA (Ambion) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following manufacturer's instructions.

ChIP Assay

A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed as described previously (17, 26). The cross-linked, sheared chromatin solution was used for immunoprecipitation with 3 μg of anti-NF-YC (C-19) antibody, anti-MR (N-17) antibody, anti-SRC-1 (M-341) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-NF-YA antibody, anti-NF-YB antibody (Abcam), and normal IgG. The immunoprecipitated DNAs were purified by using a QIAquick® PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and investigated by quantitative real-time PCR. We used the ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR® GREEN PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and primers flanking the MRE region or control region as follows: ENaC MRE sense primer, 5′-TTC CTT TCC AGC GCT GGC CAC-3′ (−1567/−1547); ENaC MRE antisense primer, 5′-CCT CCA ACG TTG TCC AGA CCC-3′ (−1317/−1297); ENaC control sense primer, 5′-ATG GGC ATG GCC AGG-3′ (+1/+15); and ENaC control antisense primer, 5′-CCT GCT CCT CAC GCT-3′ (+251/+265). DNA samples with serial dilution were amplified by PCR to determine the linear range for the amplification (data not shown).

Quantitative Real-time Reverse Transcription-PCR

The effect of endogenous NF-YC on the endogenous SgK levels in the presence of 10−8 m aldosterone was investigated by quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR. The primers/probes used in this study were as follows: NF-YC (Hs00360261_m1), SgK (Hs00178612_m1), and ENaC (Hs00168906_m1). Standard curves were generated by serial dilution of a preparation total RNA, and mRNA quantities were normalized against 18 S RNA determined by using eukaryotic 18 S rRNA endogenous control reagents (Applied Biosystems).

Immunohistochemical Staining

Tissues were isolated from 2-month-old wild-type male mice, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C, dehydrated in graded ethanol, and then processed for paraffin embedding. Primary antibodies used in this experiment were as follows: mouse anti-MR, rabbit anti-NF-YC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protocols of immunohistochemical staining were described elsewhere.

Statistics

All experiments were performed in triplicate several times. The error bars in the graphs of individual experiments correspond to the S.D. of the triplicate values. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test for unpaired comparisons (SPSS Statistics, version 17.0.1).

RESULTS

Isolation of NF-YC That Interacts with MR by Yeast Two-hybrid Screening

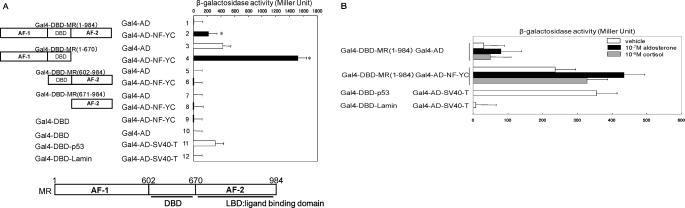

To identify proteins that regulate hormonal activity of MR, we performed a yeast two-hybrid screening with a full-length MR encoding amino acids 1–984 as bait and a cDNA library prepared from a human heart. In this manner, we identified a full-length clone of NF-YC that had a 3.5-kb insert containing an entire open-reading frame encoding 335 amino acids. NF-YC is a subunit of heterotrimeric transcription factor NF-Y that binds CCAAT box on mammalian DNA and has transcriptional activation function. First, we performed yeast two-hybrid assays to demonstrate that NF-YC interacted specifically with MR, and the interaction was specific, as no interaction between Gal4-DBD-MR (amino-acids 1–984) fusion and Gal4-activation domain (Gal4-AD: empty vector) was observed (bars 1 and 2 of Fig. 1A). In addition, NF-YC did not interact with unrelated bait corresponding to lamin (data not shown). To identify interaction domains more precisely, various fragments of MR and NF-YC were cotransformed in yeast, and β-galactosidase liquid assays were performed to quantitate the protein-protein interaction. Gal4-DBD-MR encoding amino acids 1–670 that contains activation function-1 and DNA-binding domain strongly interacted with NF-YC (bars 3 and 4 of Fig. 1A). Neither Gal4-DBD-MR encoding amino acids 602–984 that contains DNA-binding domain and ligand-binding domain nor amino acids 671–984 that has ligand-binding domain alone interacted with NF-YC (bars 5–8 of Fig. 1A). The interaction between NF-YC and MR was enhanced in the presence of 10−8 m aldosterone or 10−7 m cortisol (Fig. 1B). Taken together with the interaction data in yeast, the N-terminal fragment of MR encoding amino acids 1–602 interacted with full-length NF-YC and the interaction between NF-YC and MR was increased in the presence of aldosterone or cortisol.

FIGURE 1.

Interaction of NF-YC with human MR in yeast two-hybrid assays. A, interactions of NF-YC with full-length (1–984), N-terminal domain (1–670), C-terminal domain containing DNA- and ligand-binding domains (602–984) or C-terminal ligand-binding domain alone (671–984) of MR were determined in yeast two-hybrid assays. Statistically significant differences as compared with Gal4-AD are indicated by the asterisk (p < 0.05). B, interaction of NF-YC with full-length MR in the presence or absence of 10−7 m aldosterone or 10−6 m cortisol was determined in yeast two-hybrid assays. β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in liquid cultures in three separate experiments, each with triplicate samples. Values were expressed as the average Miller units (± S.D.) of triplicate values.

Interaction and Subcellular Localization of MR and NF-YC

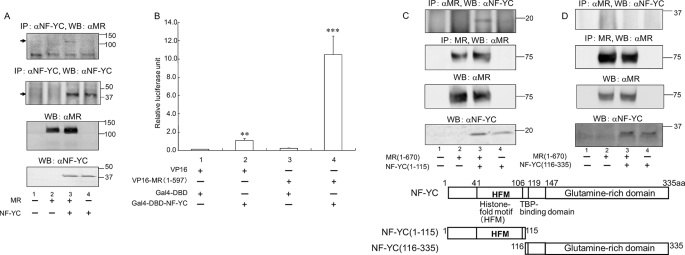

The association between MR and NF-YC was further investigated by coimmunoprecipitation assays. HEK293 cells were transfected with mammalian expression plasmids of MR and NF-YC. Polyclonal anti-NF-YC antibody was first used to precipitate the protein complexes containing NF-YC, and the presence of MR protein in these complexes was subsequently examined by immunoblotting with a polyclonal anti-MR antibody. The immunoprecipitation with anti-NF-YC antibody was considered to be effectively performed, because subsequent Western blotting with anti-NF-YC antibody successfully detected NF-YC protein bands (lanes 3 and 4 of Fig. 2A, second top panel, and supplemental Fig. S1). The presence of MR protein was detected in lysates from cells transfected with both NF-YC and MR (lane 3 of Fig. 2A, top panel), but not with NF-YC or MR alone (lanes 2 and 4 of Fig. 2A, top panel). These findings showed that NF-YC interacted with MR in mammalian cells. To define the interaction between NF-YC and N-terminal MR, we performed mammalian two-hybrid assays. COS-7 cells were transfected with the N-terminal MR (amino acids 1–597) fused to VP16 activation domain and NF-YC fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. We used each empty vector as negative controls. The Gal4-responsive reporter containing five copies of Gal4 binding sites (Gal4 × 5-Luc) was slightly induced after cotransfection of Gal4-DBD-NF-YC and empty pVP16 vector (lane 2 of Fig. 2B), indicating that NF-YC contains a transferable activation domain. In contrast, cotransfection of Gal4-DBD-NF-YC and VP16-MR-N (amino acids 1–597) markedly increased Gal4 × 5-Luc reporter activity (lane 4 of Fig. 2B). To address specific interaction between MR and NF-YC, we generated two truncated mutants of NF-YC, NF-YC-(1–115) and NF-YC-(116–335). NF-YC-(1–115) contains histone-fold motifs at the C terminus, and NF-YC-(116–335) contains glutamine-rich domain (18–22). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments utilizing these two truncated mutants and N-terminal MR showed that the N-terminal NF-YC region (1–115), but not C-terminal region (116–335), markedly interacted with N-terminal MR-(1–670) (top panel of Fig. 2, C and D). These data together with yeast two-hybrid, mammalian two-hybrid, and coimmunoprecipitation confirmed interaction between N-terminal MR and N-terminal NF-YC.

FIGURE 2.

NF-YC interacts with MR in mammalian cells. A, coimmunoprecipitation assays showed that NF-YC interacted with MR in mammalian cells. HEK293 cells were transfected with human MR-(1–984) and/or NF-YC, and the amount of DNA was kept constant by the addition of empty expression vectors. Whole cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-NF-YC antibody, and immunoprecipitates were subsequently analyzed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-MR antibody (top panel) or anti-NF-YC antibody (second panel). Levels of corresponding proteins were determined by WB with anti-MR antibody (third panel) and anti-NF-YC antibody (bottom panel). B, mammalian two-hybrid assay showed that NF-YC interacted with the N-terminal MR-(1–597). COS-7 cells were transfected with N-terminal of MR-(1–597) fused to a VP16 activation domain, NF-YC fused the Gal4 DNA-binding domain, and the Gal4-responsive luciferase reporter vector pG5-Luc. All Gal4 expression plasmids were transfected at 0.1 μg/3 wells, and the pG5-Luc and all VP16 expression plasmids were transfected at 0.5 μg/3 wells with 0.02 μg/3 wells of pRL-null. Each empty vector was used as negative controls. The cells were incubated for 18–24 h, and then luciferase activity was measured. Results are expressed as mean ± S.D. Statistically significant differences as compared with control conditions are as follows: **, p < 0.01 versus lane 1; ***, p < 0.001 versus lanes 1–3. C and D, coimmunoprecipitation assays showed that N-terminal, but not C-terminal region of NF-YC interacted with N-terminal MR. HEK293 cells were transfected with human MR-(1–670) and/or the N- or C-terminal region of NF-YC, and the amount of DNA was kept constant by the addition of empty expression vectors. Whole cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MR antibody, and immunoprecipitates were subsequently analyzed by WB with anti-NF-YC antibody (top panel) or anti-MR antibody (second panel). Levels of corresponding proteins were determined by WB with anti-MR antibody (third panel) and anti-NF-YC antibody (bottom panel).

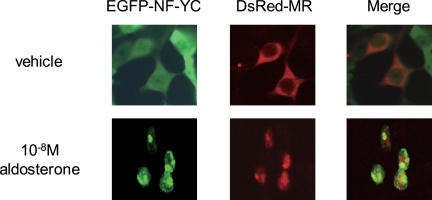

To determine whether MR and NF-YC could interact within a cellular environment, HEK293 cells were transfected with DsRed-tagged MR and EGFP-tagged NF-YC, alone or in various combinations, and photographed using fluorescence microscopy. After cotransfection of HEK293 cells with pDsRed-MR and pEGFP-NF-YC, EGFP-NF-YC was localized in both nucleus and cytoplasm in the presence of ethanol (vehicle) (Fig. 3, upper panel). Treatment with 10−8 m aldosterone resulted in nuclear accumulation of DsRed-MR and EGFP-NF-YC (Fig. 3, lower panel). These findings indicate that MR was colocalized with NF-YC in the nuclei in the presence of aldosterone.

FIGURE 3.

Subcellular localization of MR and NF-YC in cultured HEK293 cells. EGFP-NFYC was cotransfected with DsRed-MR in the presence of ethanol (vehicle) or 10−8 m aldosterone in HEK293 cells. NF-YC was colocalized with MR in the presence of aldosterone in the nuclei of the transfected HEK293 cells.

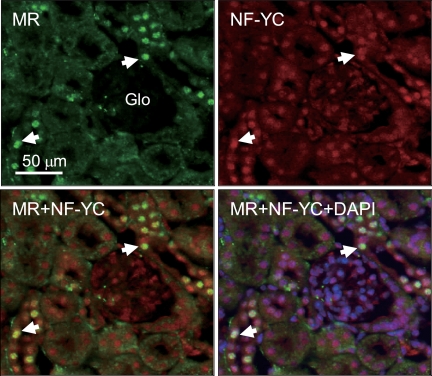

Immunohistochemistry for MR and NF-YC in the Mouse Kidney

To examine whether the physical interaction between MR and NF-YC had a potentially physiological significance, we investigated whether endogenous MR and NF-YC were indeed colocalized within the mouse kidney as an aldosterone-sensitive tissue by immunohistochemical analysis. Using specific antibody, we were able to demonstrate that MR interacted with NF-YC in the nuclei of cortical collecting duct cells of mouse kidney (Fig. 4), indicating relevance of interaction between MR and NF-YC in vivo.

FIGURE 4.

Colocalization of MR with NF-YC in the nuclei of the collecting duct cells from mouse kidney. Mouse kidney was used to immunologically detect NF-YC and MR. MR was colocalized with NF-YC in the nuclei of collecting duct cells but not glomerulus or mesangial cells. Arrows indicate representative nuclear colocalization of MR and NF-YC. The panel of MR was incubated with mouse anti-MR antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, whereas the panel of NF-YC was incubated with rabbit anti-NF-YC antibody, followed by Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG. The panel of MR+NF-YC was merged by each image. Nuclear staining was performed by using 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylidole. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Inhibitory Effect of NF-YC on MR Transactivation in a Dose- and Agonist Concentration-dependent Manner

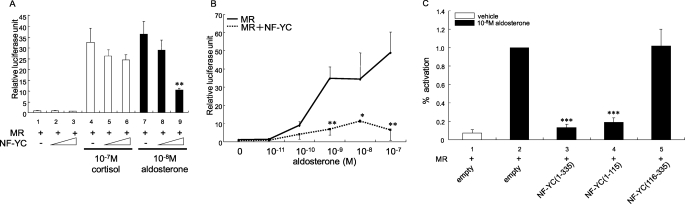

To address functional effects of interaction between MR and NF-YC, transient transfection assays were performed. Transfection of human MR cDNA expression plasmid significantly activated a reporter construct containing 3×MRE in an aldosterone-dependent manner in COS-7 cells (bar 7 of Fig. 5A). Coexpression of NF-YC repressed MR-mediated transactivation of the reporter construct in a dose-dependent manner (lanes 7–9 of Fig. 5A). The inhibitory effect of NF-YC on MR-responsive other reporters, such as MMTV-Luc and ENaC-Luc was observed in a similar manner (data not shown). Overexpression of NF-YC alone had no significant effects on the reporter activity in the absence of transfected MR (data not shown), indicating that the ability of NF-YC in repressing MR-mediated transactivation is dependent on interaction with MR. We tested the effects of ligands on the ability of NF-YC to mediated MR transcription. NF-YC had modest repressive effects on MR-mediated transcription in the presence of 10−7 m cortisol (lanes 4–6 of Fig. 5A). When increasing concentration of aldosterone treatment activated MR-mediated transactivation, coexpression of NF-YC repressed its transactivation in each concentration (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we examined which domain of NF-YC had repressive function by luciferase assays (Fig. 5C). Overexpression of the N-terminal NF-YC-(1–115) repressed aldosterone-mediated MR transactivation in a similar manner to the full-length NF-YC (lanes 3 and 4 of Fig. 5C). However, overexpression of the C-terminal NF-YC-(116–335), which has no interaction with MR, did not affect MR transactivation as expected (lanes 5 of Fig. 5C). The N-terminal NF-YC containing histone-fold motifs interacts with N-terminal MR, thus resulting in transcriptional repression. These findings indicate that interaction between MR and NF-YC is crucial to repress MR transactivation, and NF-YC is an aldosterone-dependent transcriptional corepressor of MR.

FIGURE 5.

NF-YC represses MR-mediated transcriptional activities in COS-7 cells. A, NF-YC repressed aldosterone-induced MR transactivation of a reporter gene in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.705 μg of total DNA, including 0.2 μg of MR (pRShMR), 0–0.2 μg of NF-YC construct or empty vector, and 0.005 μg of pRL-null with 0.3 μg of 3×MRE-E1b-Luc reporter DNA for each well of the 24-well dish indicated. After 18–24 h, the medium was changed to DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 10−8 m aldosterone or 10−7 m cortisol or vehicle. After an additional 24 h, cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity. Assays were performed in three separate experiments, each with triplicate samples. Statistically significant difference, as compared with a control condition (lane 7), is indicated: **, p < 0.01. B, NF-YC modulation of aldosterone-mediated transactivation properties in a concentration-dependent manner. COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.605 μg of total DNA, including 0.1 μg of MR plasmid (pRShMR), 0.005 μg of pRL-null, and 0.3 μg of 3×MRE-E1b-Luc with 0.2 μg of empty (pcDNA3.1/His) or NF-YC (pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC) plasmid. 24 h post-transfection, cells were treated with vehicle, 10−11, 10−10, 10−9, 10−8, or 10−7 m aldosterone, and cells were harvested at 48h post-transfection, and the extracts were assays for luciferase activity. Assays were performed in separate three experiments, each with triplicate samples. Statistically significant differences as compared with control conditions are as follows: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. C, the repressive function of NF-YC is located at the N-terminal region. COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.603 μg of total DNA, including 0.1 μg of MR plasmid (pRShMR), 0.03 μg of pRL-null, 0.2 μg of 3×MRE-Elb-Luc reporter DNA with 0.3 μg of various fragments of empty (pcDNA3.1/His) or various fragments of NF-YC (pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC-(1–335), pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC-(1–115), and pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC-(116–335)) for each well of the 24-well dish indicated. After 18–24 h, the medium was changed to DMEM with 10% bovine serum and 10−8 m aldosterone or vehicle. After an additional 24 h, cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity. Assays were performed with each triplicate samples. Data showed % activity of aldosterone-induced luciferase activity. Statistically significant differences as compared with control condition (lane 1) are as follows: ***, p < 0.001.

NF-YC Does Not Affect AR-, GR-, and PR-mediated Transactivation

We next examined whether NF-YC has any effect on the function of other steroid receptors by transient transfection assays. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with human AR, GRα, or PR-B cDNA expression plasmids (pcDNA3-hAR, pCMV-hGRα, and pcDNA3-hPRB), 3×MRE-E1b-Luc, and NF-YC. Expression of AR, GRα, or PR-B significantly activated a reporter construct in an agonist-dependent manner in COS-7 cells (supplemental Fig. S2, A–C). Coexpression of increasing doses of NF-YC had no significant effects on AR-, GR-, or PR-mediated transactivation, indicating that repressive function of NF-YC appears to be relatively selective for MR.

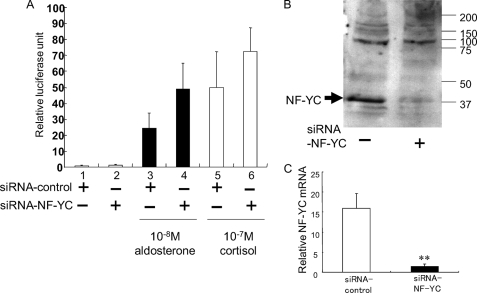

Endogenous NF-YC Contributes to MR-dependent Transrepression

If NF-YC functions as a corepressor of MR, reducing the endogenous level of NF-YC should increase the transcriptional activity by MR in transient transfection assays. Overexpression of MR activated 3×MRE-E1b-Luc reporter activity by 25-fold in the presence of aldosterone (lane 3 of Fig. 6A). To investigate the role of endogenous NF-YC in the MR transactivation, reduction of endogenous NF-YC by cotransfecting NF-YC siRNA (siRNA-NF-YC), which effectively reduced the endogenous level of protein (Fig. 6B) and mRNA (Fig. 6C) of NF-YC, increased the MR-mediated transactivation of the 3×MRE-E1b-Luc reporter construct by 2-fold in the presence of aldosterone (lanes 3 and 4 of Fig. 6A) as well as by 1.5-fold in the presence of cortisol (lanes 5 and 6 of Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Endogenous NF-YC is required for MR-dependent transrepression. A, knockdown of the endogenous NF-YC protein enhanced the MR-mediated transactivation of the 3×MRE-E1b-Luc reporter construct. COS-7 cells in 24-well dishes were transiently transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with 0.505 μg of DNA, including 0.2 μg of MR, 0.005 μg of pRL-null, and 0.3 μg of 3×MRE-E1b-Luc and 10 pmol of either NF-YC or control siRNA, as indicated. 24 h post-transfection of siRNA, plasmid DNAs were consecutively transfected, and cells were treated with 10−8 m aldosterone, 10−7 m cortisol or vehicle at 24 h after DNA transfection. 72 h post-transfection, cells were harvested, and the extracts were assayed for luciferase activity. B, Western blot analysis of endogenous NF-YC protein level that was efficiently reduced by transfection of NF-YC-specific siRNA duplex (siRNA-NF-YC) but not of negative control siRNA duplex (siRNA-control). C, quantitative real-time PCR analysis of endogenous NF-YC mRNA level that was efficiently reduced by confirmed the reduction of mRNA of NF-YC by transfection of NF-YC-specific siRNA duplex (siRNA-NF-YC) but not of negative control siRNA duplex (siRNA-control). Statistically significant difference, as compared with siRNA-control, is indicated: **, p < 0.01.

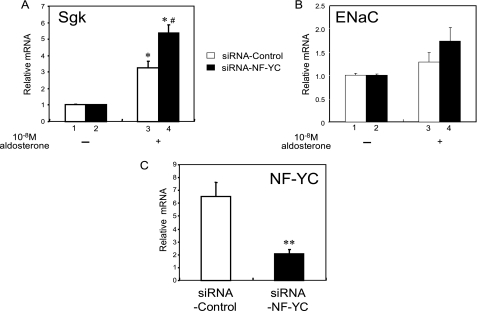

We also examined the effect of reducing endogenous NF-YC on endogenous MR target gene expression in stably MR-expressing 293-MR cells. First of all, treatment with aldosterone in 293-MR cells caused strong induction of Sgk mRNA levels by 3.3-fold, indicating that the stably expressing MR protein is physiologically functional (lane 3 of Fig. 7A). In a typical experiment, introduction of siRNA-NF-YC reduced endogenous levels of NF-YC mRNA by 30% compared with introduction of siRNA-control (Fig. 7C). In parallel with reduction of NF-YC, mRNA levels of endogenous Sgk and ENaC were reciprocally increased (Fig. 7, A and B); however, the effect was marginal on ENaC mRNA. These findings indicate that endogenous NF-YC normally functions as a transcriptional corepressor for the MR-mediated transactivation.

FIGURE 7.

NF-YC is necessary for efficient transcriptional attenuation by MR. MR-stably expressing 293-MR cells in 6-well dishes were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 with siRNA-NF-YC or siRNA control. The medium was changed to DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum at 18–24 h post-transfection. After an additional 24 h, total RNA was extracted from cells and reverse transcribed. An hour before RNA extraction, cells were treated with 10−8 m aldosterone or vehicle. The gene expression of SgK, ENaC, and NF-YC were assayed by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. A and B, levels of mRNA of Sgk and ENaC were increased by 10−8 m aldosterone (lane 3 of A and B). Reduction of endogenous NF-YC by introducing siRNA-NF-YC enhanced the mRNA levels (lane 4 of A and B). Statistically significant differences, as compared with respective control conditions, are as follows: *, p < 0.05 versus no hormone; #, p < 0.05 versus siRNA control (lane 3). C, levels of mRNA of NF-YC were efficiently reduced by introducing siRNA-NF-YC, but not siRNA control. Statistically significant difference, as compared with siRNA control, is indicated: **, p < 0.01.

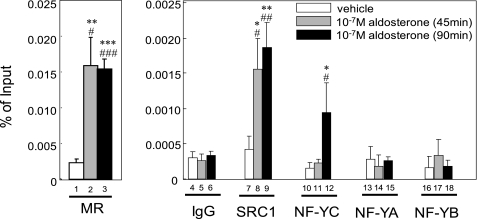

Endogenous MR and NF-YC Are Specifically Recruited to the MRE of the Human ENaC Gene Promoter

As mentioned above, the MR- NF-YC complex attenuated the MR-mediated transcription. ChIP assays were used to test whether stably expressing MR and endogenous NF-YC are recruited to the endogenous ENaC gene promoter in 293-MR cells. The cross-linked, shared chromatin preparations were subjected to immunoprecipitation with various antibodies, and the precipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR amplification of the MRE (−1567/−1297) of the ENaC promoter. We have confirmed that the size of the sonicated DNA was ∼300–600 bp, and these bands looked uniform (data not shown). After 45-min aldosterone treatment in 293-MR cells, MR and SRC-1, which was the already reported coactivator of MR, were efficiently immunoprecipitated in the MRE (−1567/−1297) of the ENaC promoter (lanes 2 and 8 of Fig. 8). But at this time, NF-YC was not recruited to the promoter (lane 11 of Fig. 8). After an additional 45 min, NF-YC was subsequently immunoprecipitated this region (lane 12 of Fig. 8). We next asked whether NF-YC alone or a complex of NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC is recruited to the ENaC promoter, because NF-YC is a subunit of heterotrimeric transcription factor NF-Y. Neither NF-YA nor NF-YB was recruited at both 45 and 90 min (lanes 13–18 of Fig. 8), indicating that, together with MR, NF-YC acts alone to repress MR transactivation. In the presence and absence of aldosterone, normal IgG and no antibody (data not shown) failed to precipitate the ENaC promoter. In contrast to the MRE of the ENaC promoter, the control region (+1/+265) of the ENaC gene was not detected in association with MR, SRC-1, or NF-YC (supplemental Fig. S3).

FIGURE 8.

NF-YC is sequentially recruited to the native αENaC promoter in an aldosterone-dependent manner followed by MR and SRC-1. For ChIP assays, when in the presence or absence (vehicle) of 10−7 m aldosterone, sheared chromatin from 293-MR cells was immunoprecipitated with anti-MR, anti-NF-YC, anti-SRC-1, anti-NF-YA, anti-NF-YB, or normal IgG. The coprecipitated DNA was amplified by quantitative real-time PCR, using primers to amplify the ENaC promoter containing MRE. At 45 min after aldosterone treatment, MR and SRC-1, interact with −1567/−1297 DNA segment containing MRE (bars 2 and 8). After additional 45 min, NF-YC sequentially interacts with −1567/−1297 DNA segment containing MRE (bar 12). Neither NF-YA nor NF-YB interacted with this region (bars 13–18). Immunoprecipitation with normal IgG (bars 4–6) was used as negative controls. Values are means ± S.D. for triplicates. Statistically significant differences as compared with control conditions are as follows: *, p < 0.05 versus 0 min; **, p < 0.01 versus 0 min; ***, p < 0.001 versus 0 min; #, p < 0.05 versus IgG; ##, p < 0.01 versus, IgG; and ###, p < 0.001 versus IgG.

These data highlight a finding that endogenous MR and NF-YC are recruited to an aldosterone-sensitive gene promoter in a largely hormone-dependent manner in the context of chromatin in vivo with a time lag. It indicated the possibility that NF-YC suppressed the excessive transactivation by coactivators such as SRC-1.

NF-YC Inhibits the Aldosterone-induced Interaction between the N- and C-terminal Regions of the MR

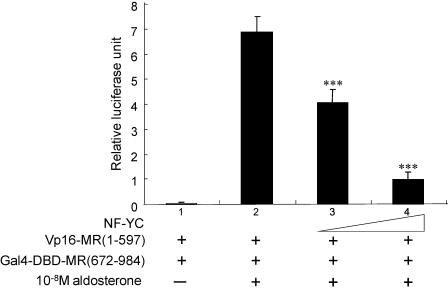

Like other steroid receptors, the conformation of MR is dramatically changed upon ligand binding. Several steroid receptors are reported in which the interaction between the N and C termini of their own occurred in the presence of their ligands (27–29). The conformational changes can be detected by intramolecular interaction between the N and C termini of MR only in the presence of aldosterone (30–33). They reported that the N/C interaction of the MR is linked to the aldosterone-induced MR activation. To determine the effect of NF-YC on the interaction between the N and C termini of MR, mammalian two-hybrid assays were performed. COS-7 cells were transfected with the N-terminal MR (amino acids 1–597) fused to the VP16 activation domain and C-terminal MR (amino acids 672–984) fused to the Gal4 DNA-binding domain. The G5-Luc reporter was strongly induced after aldosterone treatment as reported (lane 2 of Fig. 9). Of marked interest, overexpression of NF-YC inhibited the N/C interaction of MR in a dose-dependent manner (lanes 3 and 4 of Fig. 9). The results indicate that interruption of the N/C interaction of MR is involved in the corepressor function of NF-YC.

FIGURE 9.

NF-YC inhibits interaction between the N- and C-terminal MR. Interaction between the N- and C-terminal MR by 10−8 m aldosterone (lane 2) was inhibited by NF-YC (lanes 3 and 4). COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.73 μg of total DNA, including 0.17 μg of N-terminal of MR-(1–597) fused to VP16 activation domain, 0.03 μg of C-terminal region of MR-(672–984) fused to Gal4-DBD, 0.006 μg of pRL-null, and 0–0.3 μg/3 wells of NF-YC plasmid (pcDNA3.1/His-NF-YC) with 0.17 μg of the Gal4-responsive luciferase reporter vector pG5-Luc. The amount of DNA was kept constant by the addition of empty expression vector (pcDNA3.1/His-empty). 24 h post-transfection, cells were treated with either vehicle or 10−8 m aldosterone, and cells were harvested at 48 h post-transfection, and the extracts were assays for luciferase activity. Statistically significant difference as compared with control condition is indicated: ***, p < 0.001.

Repressive Function of NF-YC on MR Transactivation Does Not Depend on Histone Deacetylase Activity

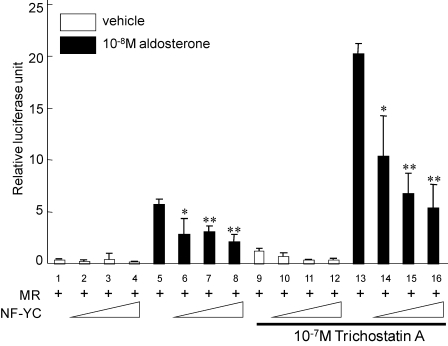

Previous studies have shown that the transcriptional repression of nuclear receptors by some corepressors, such as N-CoR and SMRT, is mediated through histone deacetylase pathways. In this regard, we investigated whether trichostatin A (TSA), a specific inhibitor of histone deacetylase activity, had any effects on the repression of the MR by NF-YC. Consistent with a previous report, treatment with 10−7 m TSA significantly increased aldosterone-induced MR transactivation by 4-fold (lane 13 of Fig. 10). However, TSA had no significant effect on the NF-YC-mediated repression (lanes 13–16 of Fig. 10), indicating that the transcriptional repression of the MR by NF-YC does not require TSA-sensitive histone deacetylase activity and that NF-YC may repress MR-mediated transactivation through other mechanisms.

FIGURE 10.

The repressive function of NF-YC on MR transactivation dose not depend on TSA-sensitive histone deacetylase activity. COS-7 cells were transfected with 0.805 μg of total DNA, including 0.2 μg of MR (pRShMR), 0–0.3 μg of NF-YC construct (pSG5-NF-YC) or empty vector (pSG5-empty) and 0.005 μg of pRL-null with 0.3 μg of 3×MRE-E1b-Luc reporter DNA for each well of the 24-well dish as indicated. After 18–24 h, the medium was changed to DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 10−8 m aldosterone or vehicle. After an additional 12 h, transfected cells were exposed to 10−7 m TSA or DMSO for 12 h. The cell extracts were assayed for luciferase activity at 48 h post-transfection. Statistically significant differences as compared with control conditions are as follows: *, p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have identified NF-YC, which interacts with the N-terminal transactivation domain of MR and can function as a corepressor of MR-mediated transcription. The yeast β-galactosidase, mammalian two-hybrid, and coimmunoprecipitation assays showed the interaction between NF-YC and MR, specifically the N-terminal MR. Transient transfection assay together with small interfering RNA and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR indicated a physiological role of NF-YC as a corepressor for the MR-dependent transactivation. Furthermore, ChIP assay showed endogenous NF-YC and MR were recruited to the promoter of the ENaC gene only in the presence of aldosterone. Colocalization of NF-YC and MR was also observed in the nuclei of intact mouse renal tubule cells as a MR target tissue, indicating that interaction between MR and NF-YC is crucial in vivo.

NF-YC meets all the criteria for a transcriptional corepressor protein in the modulation of MR transcriptional properties. First, NF-YC specifically interacted with MR in yeast and mammalian cells, and the protein-protein interaction was increased in the presence of aldosterone as shown by yeast β-galactosidase and ChIP assays. Second, overexpression of NF-YC had no effect on the reporter activities in the absence of transfected MR. However, NF-YC reduced the transactivation mediated by MR. Third, reduction of endogenous NF-YC by small interfering RNA increased MR-mediated transactivation as well as expression of endogenous Sgk and ENaC genes, indicating that endogenous NF-YC normally contributes to MR-mediated transactivation. Forth, ChIP assay showed that endogenous MR and NF-YC were recruited to a native MR-regulated ENaC promoter, demonstrating functional coupling between MR and NF-YC. Fifth, cotransfected NF-YC did not reduce the expression of MR in the coimmunoprecipitation assay, indicating that NF-YC did not affect MR protein concentration. Therefore, NF-YC has all characteristics expected for the transcriptional corepressor protein of MR.

NF-YC is a subunit of the mammalian CCAAT-specific transcription factor NF-Y (18–22). NF-Y is a heterotrimeric transcription factor that is composed of NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC and activates transcription by binding to the CCAAT box present in ∼30% of eukaryotic promoters and enhancer regions. All of the subunits are necessary for CCAAT binding. Each subunit has a core region, which has been conserved throughout evolution. The conserved regions of the two subunits NF-YB and NF-YC contain histone fold motifs, which are required for the heterodimerization as a prerequisite for NF-YA association and CCAAT binding (18, 34, 35). The presence of histone fold motifs in the NF-YB and NF-YC implicates these proteins as being likely to have multiple protein-protein interactions with other transcription factors as well as being given protein modifications. The NF-YA and NF-YB/NF-YC heterodimer were shown to be separately imported to the nucleus through Importins β and 13, respectively (36). However, our coimmunoprecipitation and ChIP assays showed that NF-YC alone, not a complex of NF-YA, NF-YB, and NF-YC, is recruited to a MR-responsive ENaC gene promoter, thus resulting in MR-mediated transcriptional repression. We therefore conclude that NF-YC can function as a ligand-dependent MR corepressor.

Transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors is mediated by recruitment of coactivators and corepressors. Several models of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction have been currently delineated (37, 38). In the classic model, unliganded non-steroidal receptors, such as thyroid hormone receptor, bind corepressors, the silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT), or N-CoR, thus resulting in basal repression with recruitment of histone deacetylases, whereas ligand binding releases these corepressors and then recruits coactivator complexes and induces hormone-dependent transactivation. In the second model, both N-CoR and SMRT are shown to strongly bind antagonist-bound steroid receptors, including estrogen receptor. In that model, these corepressor molecules are considered to be responsible for antagonist action for the receptor. Recent reports showed a new paradigm that corepressors are recruited to the nuclear receptors even in the presence of agonist. N-CoR and SMRT are shown to be recruited to the vitamin D/retinoid X receptor heterodimers in a vitamin D3-dependent manner (37). Besides these corepressors, new corepressors, such as L-CoR (39) and REA (40), are shown to be involved in agonist-bound estrogen receptor. The mode of corepressor function implicates that these corepressors can function as physiological negative regulators of nuclear receptor transcription, because recruitment of the corepressor occurs strictly in the presence of agonist. Based on these findings, corepressors play multiple roles in nuclear receptor-mediated hormone action: basal repression, antagonist action, and negative regulator against agonist action. We have isolated NF-YC as the first corepressor of agonist-bound MR. In line with the new mode, we observed that treatment with TSA potentiated aldosterone-mediated MR transactivation, indicating that TSA-sensitive histone deacetylases are involved in the multiple coactivator complexes. However, the corepressor function of NF-YC was not canceled by treatment with TSA. We therefore assume that NF-YC plays a physiological negative regulator of aldosterone-mediated MR transactivation independent of TSA-sensitive histone deacetylases. The NF-YC recruitment to the MR in a strictly aldosterone-dependent manner may explain why NF-YC plays a crucial role in fine-tuning MR-dependent transactivation. Of marked interest, our ChIP assay showed that both MR and SRC-1 were recruited to the ENaC promoter, followed by delayed recruitment of NF-YC. The physiological significance of the sequential recruitment of SRC-1 followed by NF-YC to the MR is not known at present; however, it may implicate that NF-YC acts as an “emergency brake” of excessive aldosterone action.

At the pre-receptor level, ligand selectivity is regulated by 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 that is coexpressed in MR target tissue; however, molecular mechanisms of MR transactivation beyond ligand binding are not known. Intramolecular interaction of the N- and C-terminal AR has been investigated in the presence of agonist. The conformational changes are considered to be crucial for testosterone-mediated AR transcription. Although both aldosterone and cortisol can bind MR with equal affinity and induce MR transactivation, the N/C interaction occurs only in the presence of aldosterone, but not cortisol (31–33). We therefore assume that the conformational structure and mechanism of MR transactivation mediated by aldosterone and cortisol are different. In line with our data that the repressive effect of NF-YC on MR transactivation was more obvious in the presence of aldosterone than cortisol, we assume that NF-YC may affect the N/C interaction of MR induced by aldosterone. In fact, our mammalian two-hybrid assays showed overexpression of NF-YC inhibited the N/C interaction of MR induced by aldosterone, indicating that MR interaction with NF-YC affects aldosterone-induced conformational changes. This may be one of the mechanisms of corepressor function of NF-YC for MR.

These results clearly showed that NF-YC is a newly identified corepressor of agonist-bound MR. Interaction between MR and NF-YC was specific in several different interaction assays, including yeast two-hybrid, mammalian two-hybrid, coimmunoprecipitation, subcellular imaging, ChIP, and immunohistochemical stainings in intact animal. To explore the pathophysiological role of NF-YC in the MR function, it should be important to investigate whether the level of expression of NF-YC is changed under pathological states in animal models in the future. Because MR has been highlighted as an important pathogenic mediator of cardiac and vascular remodeling, therapeutic interventions that affect MR-NF-YC interaction or levels of expression of NF-YC may be a novel strategy to protect cardiovascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Bert W. O'Malley, Dr. Ronald M. Evans, Dr. Peter J. Fuller, Dr. John A. Cidlowski, Dr. Christie P. Thomas, and Dr. Robert Mantovani for plasmid contributions.

This work was supported by an investigator-initiated research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Inc. (to H. S.), a Health Labor Science Research Grant for Disorders of Adrenocortical Hormone Production from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (to H. S.), Keio Gijuku Fukuzawa Memorial Fund for the Advancement of Education and Research (to H. S.), Keio Gijuku Academic Development Funds (to H. S.), and a grant from Smoking Research Foundation (to H. I. and H. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- MR

- mineralocorticoid receptor

- NF-YC

- nuclear transcription factor C

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- DsRed

- Discosoma sp. Red

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- WB

- Western blot

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- AR

- androgen receptor

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- PR

- progesterone receptor

- Sgk

- serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase

- ENaC

- epithelial sodium channel

- SRC-1

- steroid receptor coactivator-1

- E2

- ubiquitin carrier protein

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- SMRT

- silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptor

- N-CoR

- nuclear receptor corepressor

- MRE

- mineralocorticoid-responsive element

- DBD

- DNA-binding domain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Viengchareun S., Le Menuet D., Martinerie L., Munier M., Pascual-Le Tallec L., Lombès M. (2007) Nucl. Recept. Signal. 5, e012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang J., Young M. J. (2009) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 43, 53–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitt B., Zannad F., Remme W. J., Cody R., Castaigne A., Perez A., Palensky J., Wittes J. (1999) N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 709–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitt B., Remme W., Zannad F., Neaton J., Martinez F., Roniker B., Bittman R., Hurley S., Kleiman J., Gatlin M. (2003) N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1309–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKenna N. J., O'Malley B. W. (2002) Cell 108, 465–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith C. L., O'Malley B. W. (2004) Endocr. Rev. 25, 45–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hermanson O., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (2002) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 13, 55–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamei Y., Xu L., Heinzel T., Torchia J., Kurokawa R., Gloss B., Lin S. C., Heyman R. A., Rose D. W., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G. (1996) Cell 85, 403–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y., Suino K., Daugherty J., Xu H. E. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 367–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oñate S. A., Tsai S. Y., Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. (1995) Science 270, 1354–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenfeld M. G., Glass C. K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36865–36868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascual-Le Tallec L., Simone F., Viengchareun S., Meduri G., Thirman M. J., Lombès M. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 1158–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hultman M. L., Krasnoperova N. V., Li S., Du S., Xia C., Dietz J. D., Lala D. S., Welsch D. J., Hu X. (2005) Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 1460–1473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S. K., Anzick S. L., Choi J. E., Bubendorf L., Guan X. Y., Jung Y. K., Kallioniemi O. P., Kononen J., Trent J. M., Azorsa D., Jhun B. H., Cheong J. H., Lee Y. C., Meltzer P. S., Lee J. W. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34283–34293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuse H., Kitagawa H., Kato S. (2000) Mol. Endocrinol. 14, 889–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitagawa H., Yanagisawa J., Fuse H., Ogawa S., Yogiashi Y., Okuno A., Nagasawa H., Nakajima T., Matsumoto T., Kato S. (2002) Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 3698–3706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Yokota K., Shibata H., Kurihara I., Kobayashi S., Suda N., Murai-Takeda A., Saito I., Kitagawa H., Kato S., Saruta T., Itoh H. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1998–2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellorini M., Zemzoumi K., Farina A., Berthelsen J., Piaggio G., Mantovani R. (1997) Gene 193, 119–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Silvio A., Imbriano C., Mantovani R. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 2578–2584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frontini M., Imbriano C., Manni I., Mantovani R. (2004) Cell Cycle 3, 217–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani R. (1999) Gene 239, 15–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matuoka K., Yu Chen K. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 253, 365–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durfee T., Becherer K., Chen P. L., Yeh S. H., Yang Y., Kilburn A. E., Lee W. H., Elledge S. J. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 555–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibata H., Nawaz Z., Tsai S. Y., O'Malley B. W., Tsai M. J. (1997) Mol. Endocrinol. 11, 714–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi S., Shibata H., Kurihara I., Yokota K., Suda N., Saito I., Saruta T. (2004) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 32, 69–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurihara I., Shibata H., Kobayashi S., Suda N., Ikeda Y., Yokota K., Murai A., Saito I., Rainey W. E., Saruta T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6721–6730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Métivier R., Penot G., Flouriot G., Pakdel F. (2001) Mol. Endocrinol. 15, 1953–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tetel M. J., Giangrande P. H., Leonhardt S. A., McDonnell D. P., Edwards D. P. (1999) Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 910–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Z. X., Lane M. V., Kemppainen J. A., French F. S., Wilson E. M. (1995) Mol. Endocrinol. 9, 208–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pippal J. B., Yao Y., Rogerson F. M., Fuller P. J. (2009) Mol. Endocrinol. 23, 1360–1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogerson F. M., Brennan F. E., Fuller P. J. (2003) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 85, 389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogerson F. M., Brennan F. E., Fuller P. J. (2004) Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 217, 203–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogerson F. M., Fuller P. J. (2003) Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 200, 45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bellorini M., Lee D. K., Dantonel J. C., Zemzoumi K., Roeder R. G., Tora L., Mantovani R. (1997) Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 2174–2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romier C., Cocchiarella F., Mantovani R., Moras D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1336–1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahle J., Baake M., Doenecke D., Albig W. (2005) Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 5339–5354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurevich I., Flores A. M., Aneskievich B. J. (2007) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 223, 288–298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sánchez-Martínez R., Zambrano A., Castillo A. I., Aranda A. (2008) Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 3817–3829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernandes I., Bastien Y., Wai T., Nygard K., Lin R., Cormier O., Lee H. S., Eng F., Bertos N. R., Pelletier N., Mader S., Han V. K., Yang X. J., White J. H. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montano M. M., Ekena K., Delage-Mourroux R., Chang W., Martini P., Katzenellenbogen B. S. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 6947–6952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.