Abstract

Extracellular ATP represents an important autocrine/paracrine signaling molecule within the liver. The mechanisms responsible for ATP release are unknown, and alternative pathways have been proposed, including either conductive ATP movement through channels or exocytosis of ATP-enriched vesicles, although direct evidence from liver cells has been lacking. Utilizing dynamic imaging modalities (confocal and total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy and luminescence detection utilizing a high sensitivity CCD camera) at different scales, including confluent cell populations, single cells, and the intracellular submembrane space, we have demonstrated in a model liver cell line that (i) ATP release is not uniform but reflects point source release by a defined subset of cells; (ii) ATP within cells is localized to discrete zones of high intensity that are ∼1 μm in diameter, suggesting a vesicular localization; (iii) these vesicles originate from a bafilomycin A1-sensitive pool, are depleted by hypotonic exposure, and are not rapidly replenished from recycling of endocytic vesicles; and (iv) exocytosis of vesicles in response to cell volume changes depends upon a complex series of signaling events that requires intact microtubules as well as phosphoinositide 3-kinase and protein kinase C. Collectively, these findings are most consistent with an essential role for exocytosis in regulated release of ATP and initiation of purinergic signaling in liver cells.

Keywords: Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases, Subcellular Organelles/Vesicles, Tissue/Organ Systems/Liver, Transport, Purinergic Receptor, ATP Release, Purinergic Signaling, Exocytosis, Nucleotides

Introduction

Extracellular ATP functions within liver as a key autocrine/paracrine signaling molecule. The purinergic signaling cascade is initiated by release of ATP from intracellular stores, but the mechanisms involved are poorly understood. However, P2 receptors are expressed on all liver cell types, and once outside of the cell ATP has multiple effects, including (i) coordination within the liver lobule of cell-to-cell [Ca2+]i signaling (1), (ii) maintenance of cell volume within a narrow physiological range (2), and (iii) coupling of the separate hepatocyte and cholangiocyte contributions to bile formation and stimulation of biliary secretion (3). Specifically, cellular ATP release leads to increased concentrations of ATP in bile sufficient to activate P2 receptors in the apical membrane of targeted cholangiocytes, resulting in a robust secretory response through activation of Cl− channels in the apical membrane. Moreover, multiple signals including intracellular calcium, cAMP and bile acids appear to coordinate ATP release, which has been recognized recently as a final common pathway responsible for biliary secretion (3–5). Accordingly, definition of the mechanisms involved in ATP release represents a key focus for efforts to modulate liver function and the volume and composition of bile.

Previous studies indicate that increases in cell volume serve as a potent stimulus for physiologic ATP release in many epithelia and in liver cells increase extracellular nucleotide concentrations 5–10-fold (6). Two broad models for ATP release by nonexcitatory cells have been proposed, including (i) opening of ATP-permeable channels and/or (ii) exocytosis of ATP-containing vesicles (7). There is evidence, for example, for conductive movement of ATP4− across the plasma membrane, consistent with a channel-mediated mechanism, and connexin 36 hemichannels (8), ATP-binding cassette proteins, and P2X7 receptor proteins (9) each have been proposed to function as ATP-permeable transmembrane pores where opening permits movement of ATP from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space (10). Alternatively, ATP can be co-packaged into vesicles with other signaling molecules in endothelial and chromaffin cells, and exocytosis results in rapid point source increases in extracellular ATP concentrations (11, 12). Quinacrine taken up by the cell is concentrated in ATP-containing vesicles, and fluorescence imaging of intracellular ATP stores in pancreatic acinar cells shows a punctate distribution consistent with a vesicular localization (13). Given the diverse functions of ATP as an agonist, it is likely that more than one pathway is operative with substantial differences among cell types in the mechanisms involved.

In the liver, expression of the ATP-binding cassette protein MDR1 increases ATP release, but the effects of P-glycoproteins on ATP release can be dissociated from P-glycoprotein substrate transport, suggesting that MDR1 per se is not likely to function as an ATP channel (14). Similarly, in biliary cells, the related cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) is expressed in the apical membrane and plays an important regulatory role in ATP release through a mechanism not yet defined (3, 15). Recent indirect observations suggest an important role for vesicular pathways in hepatic ATP release. In a cholangiocyte cell line, increases in cell volume stimulate an abrupt increase in exocytosis to rates sufficient to replace 15–30% of plasma membrane surface area within 1 min through a mechanism dependent on both protein kinase C and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, and interruption of this exocytic response inhibits volume-sensitive ATP release (16). Similarly, intracellular dialysis through a patch pipette with the lipid products of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the absence of an increase in cell volume is sufficient to stimulate ATP release (6, 17). Together, these findings suggest that functional interactions between cell volume and exocytosis modulate purinergic signaling in liver through effects on ATP release. Accordingly, the purpose of these studies was to assess the kinetics of volume-sensitive ATP release, to assess whether liver cells possess vesicles enriched in ATP, and to determine whether exocytosis and ATP release are functionally related.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Models

Studies were performed in HTC rat hepatoma cells, which express all components of the P2-signaling axis, including mechanosensitive ATP release, Ca2+ signaling, and coupled changes in ion permeability (2, 6, 18). Cells were passaged at weekly intervals and maintained in HCO3−-containing minimal essential medium (Invitrogen), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 IU/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37 °C in 5% CO2 as described previously (19).

Luminometry

Bulk ATP release was studied from confluent cells using the luciferin-luciferase (L-L)2 assay as described previously (20). Cells were grown to near confluence on 35-mm tissue culture-treated dishes (Falcon, BD Biosciences) and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (600 μl, twice). 600 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) containing L-L (Fl-ATP assay mix, Sigma; reconstituted according to the manufacturer's directions and used at a final dilution of 1:50 with Opti-MEM) was added, and then cells were placed into a modified Turner TD 20/20 Luminometer in complete darkness. After a 5–10-min equilibration period, readings were obtained every 15 s, and cumulative bioluminescence over 15-s photon intervals was quantified in real time as arbitrary light units (ALU). Studies were performed at room temperature because luciferase activity decreases at higher temperatures (21, 22).

Point Source Chemiluminescence Assay

Cells were grown to near confluence on 35-mm tissue culture-treated dishes, and media were removed. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline, L-L (1:25 dilution) was added, and cells were placed in a light-tight box with optical imaging apparatus and attached to a perfusion system (Pump 33, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). The perfusion system allowed delivery of the hypotonic stimulus to the cells without interrupting imaging or opening the light-sealed chamber. Light produced by the catalysis of the L-L reaction by released ATP was detected by a high sensitivity electron-multiplying CCD camera (Princeton Instruments/ACTON PhotonMAX 512B with the e2v CCD97 sensor, 512 × 512 pixels), mounted in a vertical orientation on an x-y-z stage. A relay lens consisting of two 25.4-mm format lenses (Schneider Xenon f/# 0.95) coupled front-to-front with each focused at infinity with full aperture was used to image at 1×, similar to macroscopic geometries previously utilized in CCD-based γ-camera configurations (23, 24). Focusing was performed by translating the z axis. Images were collected at a frequency of 9–10 Hz with a 100-ms exposure time during basal (isotonic) and hypotonic conditions. Typical stacks of 500–700 images were streamed to hard disk for storage and data analysis. Full electron-multiplication stage gain was utilized in all experiments for maximum sensitivity. Base-line image stacks prior to hypotonic stimulation were also obtained for residual ATP detection and electron-multiplication noise characterization. Precautions were taken to avoid overexposure of the high-gain sensor mode because this has been shown to reduce sensitivity.

Cell Staining

Quinacrine (Sigma), an acridine derivative, has a very high affinity for ATP and has been utilized to label intracellular ATP-enriched vesicles in neuronal and epithelial cell types (12, 13, 25–28). Cells cultured on Lab-Tech glass-bottom 8-well imaging coverglasses (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY), were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and stained with quinacrine (5 μm × 5 min), washed, and placed in isotonic buffer. In select studies, FM 4-64 (4 μm for 10–120 min; Invitrogen/Molecular Probes), to label the plasma membrane and endocytic vesicles, preceded or was administered concurrently with quinacrine as indicated.

Confocal Imaging

Cells were culture on Lab-Tek 8-well chambered coverglass (Nalge Nunc), stained with FM 4-64 and quinacrine and imaged under basal and hypotonic conditions as described above. Imaging was performed using a PerkinElmer Biosciences UltraVIEW ERS spinning disk confocal microscope (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). An argon ion laser and a krypton laser (Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) were utilized as a light source (excitation at 488 and 561 nm, respectively), and data were captured with a Hamamatsu ORCA-AG high resolution cooled CCD (Hamamatsu Photonics, Bridgewater, NJ) controlled by the UltraVIEW ERS software. Images were recorded using a Zeiss Plan Apo ×63/1.40 numerical aperture oil immersion objective lens. Fast multicolor images were captured using emission band pass filters to allow effective separation of overlapping wavelengths, and 2 × 2 binning was selected for all images. Speed of acquisition was increased by subarraying the camera to reduce the size of the captured image. Image analysis was performed utilizing ImageJ (available on the World Wide Web), and Imaris 5.0 (Bitplane Inc., Saint Paul, MN) was used for three-dimensional volume rendering of z stacks after background correction and edge-enhancing anisotropic diffusion filtering. The Imaris spot detection algorithm was applied to detect and measure objects (vesicles) after specifying minimum diameter so that speckle noise was not detected. We defined small vesicles as those between 0.4 and 0.99 μm versus large vesicles, defined as those of ≥1 μm. Potential co-localization between FM4-64- and quinacrine-labeled vesicles was evaluated by application of Imaris 5.0–6.2 (Bitplane, Inc.) utilizing the co-localization feature, with complete (100%) co-localization indicated by a Person's coefficient of ≥1.00.

Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Imaging

Cells were cultured on a Lab-Tek 8-well chambered coverglass (Nalge Nunc), stained with quinacrine, and imaged under basal and hypotonic conditions, as described above. TIRF imaging was performed on an Olympus IX71 microscope equipped with an Olympus TIRF module. Quinacrine TIRF was excited with the 488-nm line of a 10-milliwatt argon laser (Melles Griot) through a ×60 PlanApo-N 1.45 numerical aperture oil immersion lens or a PLAPO ×100 1.45 numerical aperture TIRF microscope oil immersion lens as described (29, 30). Laser intensity was modulated by neutral density filters and Uniblitz electronic shutters (Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY). Time-lapse images were acquired every 300 ms with exposure times of 100–200 ms using SlideBook (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Inc., Denver, CO) to control a Hamamatsu Orca II ERG camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) and the electronic shutters.

Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Release

LDH measurements were performed pre- and posthypotonic exposure using an enzymatic colorimetric cytotoxicity assay (CytoTox 96, Promega, Madison, WI). Calibration of the assay was performed with cell-free controls and reagents only (no LDH release), LDH standard at a dilution of 1:5000 (amount of LDH in ∼13,000 lysed cells), and after exposure of cells to lysis solution (maximum LDH release).

Reagents

Wortmannin was obtained from Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences (La Jolla, CA), and calphostin C was obtained from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). All other reagents were obtained from Sigma. None of the reagents affected L-L luminescence as measured during cell-free conditions.

Statistics

Results are presented as the means ± S.E., with n representing the number of culture plates or repetitions for each assay as indicated. Statistical analysis included Fisher's paired and unpaired t test and analysis of variance for multiple comparisons to assess statistical significance as indicated, and p values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Identification of Point Source Bursts of ATP Release from Liver Cells

Increases in liver cell volume result in an increase in bulk ATP concentration in the overlying media from ∼10 to ∼300 nm as measured by luciferin-luciferase bioluminescence (31). This response represents an integrated signal from >106 cells, peaks within ∼90 s, and gradually decays over minutes. In order to visualize the dynamics of ATP release, direct imaging of ATP in solution was performed using real-time bioluminescence to detect extracellular ATP across a field of cells (10). For these studies, cells in culture were superperfused with luciferin-luciferase-containing medium, maintained in a dark environment, and imaged with a high sensitivity electron-multiplying CCD camera (see supplemental Fig. S1). Under these conditions, the appearance of ATP in the medium was detected in real time by light emissions resulting from ATP-dependent luciferase-catalyzed oxidation of luciferin (10). A representative sequence of images from a single plate of cells is shown in Fig. 1. Under basal conditions, there was low background activity. When medium osmolality was reduced (by 33%) to produce an increase in cell volume, there was an increase in luminescence, but it was not evenly distributed across the field of cells. Rather, there were abrupt point source bursts of high intensity. Each burst reached maximal intensity within <2 s (the dead time of the instrument) and then decayed with t½ of 4.9 s as shown in Fig. 1. The maximal diameter of detectable ATP bursts averaged 201 ± 11 μm (n = 31). In the presence of high dose suramin to block P2 receptors, the average size of the individual events was unaffected (diameter 231 ± 18 μm, not significant, n = 13), confirming that each burst was a discrete event and did not represent propagation of ATP-dependent ATP release from neighboring cells. Further, ATP release was restricted to single events, in that there was no evidence for subsequent open events at the same site. Finally, luminescence was eliminated completely by exposure to apyrase (1 unit/ml) to hydrolyze ATP (data not shown); there was no associated release of LDH and no evidence of cell injury or necrosis when visualized by conventional microscopy (not shown). Thus, volume-sensitive ATP release is not uniform but occurs as focal points of high intensity across a population of cells. Each event is discrete and nonrecurring and produces a localized zone of increased ATP concentration that diffuses rapidly over a range corresponding to ∼10 cell diameters before dropping to undetectable levels, consistent with the published values of the ATP diffusion coefficient and suggesting an autocrine/paracrine sphere of signaling.

FIGURE 1.

Point source ATP release. ATP release was detected from confluent HTC cells as focal increases in bioluminescence generated by ATP-dependent luciferin breakdown by luciferase (see supplemental Fig. S1). A, time lapse images of a representative study. Hypotonic solution was perfused onto confluent cells (shown in the first frame, bright field image; scale bar, 50 μm) from a pipette immediately above the cells and to the right of view (indicated by small gray triangle in the last frame). The first image was obtained 2 s after hypotonic addition, and sequential images (from left to right and top to bottom) represent 500-ms intervals. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, relative change in bioluminescence of the example shown in A. Total bioluminescence is shown as a solid line, and one individual burst event is shown as a dotted line. The maximal burst diameter was measured for 31 bursts, and the mean ± S.E. is shown in the inset.

Evidence for ATP-enriched Vesicles

This temporal profile of extracellular ATP kinetics is most compatible with point source release and rapid ATP diffusion/hydrolysis. In an effort to visualize candidate vesicles containing ATP, cells were preincubated with quinacrine, which has a high affinity for ATP and, when exposed to blue light, produces a concentration-dependent fluorescence (13). Fig. 2, using TIRF microscopy to visualize the submembrane space of ∼100 nm adjacent to the coverslip, demonstrates that that quinacrine visualization of cellular ATP stores is not uniform. Rather, fluorescence is detected as discrete foci 0.5–1.0 μm in diameter, which vary in intensity over a 4-fold range. When visualized in real time, these focal regions of high intensity are not static but vacillate in a Brownian manner. Further, occasional vesicles move toward the membrane and demonstrate a transient increase in fluorescence intensity followed by rapid disappearance (see supplemental Fig. S2). This transient increase in intensity is analogous to exocytosis of pancreatic secretory vesicles loaded with acridine orange (32), suggesting concentration of quinacrine (and presumably ATP) within a population of vesicles and subsequent exocytic release of quinacrine/ATP into the extracellular space (Fig. 2B). Although Figs. 1 and 2 are visually similar, Fig. 1 corresponds to macroscopic visualization of extracellular ATP diffusing over ∼200 μm, and Fig. 2 detects intracellular stores packaged into discrete domains of ∼1 μm. Under basal conditions (23 °C), these release events occurred spontaneously at a rate of 0.13 ± 0.06 events/cell/min (Fig. 2C). Increases in cell volume (33% decrease in osmolality) increased the rate to 0.88 ± 0.27 events/cell/min (n = 35, p < 0.01). Moreover, increasing temperature to 35 °C increased both basal (0.73 ± 0.09 events/cell/minute) and volume-sensitive (1.48 ± 0.19 events/cell/min) responses (n = 41 for each, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 2.

TIRF microscopy reveals a population of submembrane quinacrine-rich vesicles. HTC cells were loaded with quinacrine (10 min), and the submembrane space to a depth of ∼100 nm was illuminated by the evanescent field generated during TIRF. A, time lapse images of single vesicle exocytosis. The dotted white line outlines approximate plasma membrane of one cell. Quinacrine fluorescence appears in focal areas of high concentration ∼1 μm in diameter. In response to hypotonic exposure (33%), vesicles increase in mobility and occasionally fuse with the plasma membrane in a “burst” of fluorescence (see supplemental Fig. S2 of this cell). These sequential images (from left to right and from top to bottom) represent the same cell at 720-ms intervals. A yellow arrowhead marks the position of one representative exocytic event in this field of view. In this example, fluorescence intensity increases sharply, is accompanied by an increase in the diameter of the fluorescent burst, and then rapidly decreases in intensity back to basal levels. Scale bar, 5 μm. B, fluorescence intensity of the single event shown in A was quantified by enclosing the vesicle in a circle and measuring the fluorescence intensity over time. Red hash marks indicate the period of time represented in the images shown in A. C, cumulative data demonstrating total number of events per cell imaged during TIRF at both 23 °C and 35 °C. Black bar, basal events; gray bar, events after hypotonic exposure (33% decrease in osmolality), mean ± S.E. for 35–42 individual cells each. *, hypotonic versus basal at 23 °C, n = 35 each, p < 0.01. #, basal at 35 °C (n = 42) versus basal at 23 °C (n = 35), p < 0.01; **, hypotonic versus basal at 35 °C, n = 42 each, p < 0.01; ##, hypotonic at 35 °C (n = 42) versus hypotonic at 23 °C (n = 35), p < 0.05.

Total Cellular ATP Vesicles

Similar results were obtained when quinacrine-enriched vesicles were assessed using digital reconstruction of spinning disk confocal z stacks to estimate the size of the vesicular pool involved (Fig. 3A). In the example shown, the plasma membrane is shown in red (FM4-64), and vesicles are shown in green (quinacrine). Exposure to hypotonic medium decreased the total number of quinacrine-stained vesicles in responding cells by 76 ± 8% (n = 14 cells); which represented a decrease of 76 ± 6% of small (0.4–0.99-μm) and a decrease of 58 ± 8% of large (≥1-μm) vesicle populations (Fig. 3C). Similar to the point source ATP bursts described above, not all cells within a given area reacted similarly, with a loss of quinacrine vesicles, in response to the hypotonic stimulus. In confluent cell preparations, 69 ± 14% of cells responded to a hypotonic stimulus with a loss of quinacrine-labeled vesicles, as shown in this representative example (Fig. 3B). Together, these findings are compatible with previous studies demonstrating close coupling between volume-stimulated exocytosis and ATP release. Moreover, the findings suggest that the ATP-containing vesicular pool might be limited in size and subject to depletion over the time course of these studies. Loss of quinacrine-stained vesicles was not due to photobleaching because cells exposed to isotonic solution and then imaged under identical conditions did not lose fluorescence (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Confocal imaging and three-dimensional reconstruction of HTC cells dually labeled with quinacrine and FM4-64. A, representative single cell. Prehypotonic (top) and 1 min posthypotonic (33%) (bottom) exposure are shown. Large grid squares represent 1 μm. B, representative confluent monolayer. Prehypotonic (top) and 1 min posthypotonic (33%) (bottom) exposure are shown. A spot detection algorithm was applied to count small (0.4–0.99 μm, gray spheres) and large (≥1 μm, blue spheres) vesicles during basal conditions and 1 min after equal volumes of either isotonic or hypotonic buffers were applied. Representative responding cells (defined as a loss of ≥5% of total vesicles) and nonresponding cell are outlined in yellow and white boxes, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, cumulative data of responding cells reported as percentage of remaining vesicles per cell. Note that only responding cells are included in the analysis. The numbers of total (dark gray bar), large (black bar), and small (light gray bar) vesicles all decreased in response to hypotonic exposure. *, p < 0.01 versus isotonic for each (n = 14).

ATP Vesicle Formation Is Dependent on V-type ATPase

To determine the origin of the ATP-enriched vesicles, a dual staining strategy was employed with quinacrine and FM4-64 to label endosomes (Fig. 4). Two staining protocols were utilized: (i) concurrent FM4-64 and quinacrine staining in which cells were incubated with both dyes and imaged at defined time points for up to 45 min and (ii) sequential labeling in which cells were first exposed to FM4-64 for 15–120 min and then dye was removed, followed by exposure to quinacrine and imaging at the defined time points. Utilizing these protocols, two vesicle populations were observed: endocytic vesicles due to incorporation of FM4-64-stained plasma membrane and a second pool of quinacrine-labeled vesicles that was distinct from the FM4-64 endocytic pool. No dual staining was observed within 30 min of labeling (Pearson's coefficient = 0.42) with either of the protocols. However, co-localization was observed at 45 min with 96% of the quinacrine-labeled vesicles co-localizing with the FM4-64-labeled vesicles (Pearson's coefficient = 0.85). The same staining protocol was utilized after cells were exposed to hypotonicity (33%) to determine if endosomal or rapid refilling occurs after an ATP-depleting stimulus. Once again, no dual labeling was identified until 30 min postexposure (data presented in supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Together, these studies demonstrate that the quinacrine-labeled vesicles do not co-localize with the FM4-64-labeled vesicles until after 30 min, suggesting that these vesicles may derive from a late endosomal compartment. No co-localization was observed at early time points (before 30 min), excluding rapid refilling of early endosomes as a source of the ATP-enriched compartment.

FIGURE 4.

Formation of quinacrine vesicles. HTC cells labeled with FM4-64 and quinacrine and imaged with confocal microscopy as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, in the continuous presence of quinacrine (green) and FM4-64 (red), no significant co-localization (yellow) is observed until 45 min (Pearson's coefficient = 0.85). Scale bar, 10 μm. B, bafilomycin A1 inhibits quinacrine vesicle formation and ATP release. First column, quinacrine; second column, FM4-64; third column, merged images. Top row, control; bottom row, postincubation with bafilomycin A1 (4 μm for 30 min). Scale bar, 10 μm. C, bulk ATP release (measured as arbitrary light units) was measured from confluent HTC cells after isotonic and hypotonic (33%) exposures in control (black circles) or after incubation with bafilomycin A1 (open circles). Each point represents mean ± S.E. for n = 7 trials each. *, basal, isotonic, and hypotonic buffer-stimulated ATP release was significantly inhibited, p < 0.01.

Bafilomycin A1, a macrolide antibiotic, is a potent inhibitor of V-type ATPase and impairs storage of ATP in chromaffin granules and secretory vesicles in astrocytes (28). Incubation of cells with bafilomycin (4 μm × 30 min) significantly inhibited the appearance of quinacrine-stained ATP vesicles 1.12 ± 0.48 versus control 31.62 ± 3.35 vesicles/unit area (square pixels), n = 8 each, p < 0.01 (Fig. 4B, bottom). In complementary real-time measurements of ATP release, bafilomycin blocked basal (57.9 ± 9.1 ALU), mechanically stimulated (67.6 ± 11.1 ALU), and volume-stimulated (92.6 ± 17.1 ALU) ATP release versus control (219.3 ± 4.3, 251.4 ± 7.8, and 384.4 ± 9.1 ALU, respectively, n = 7 trials each, p < 0.01 (Fig. 4C)). Together, these studies demonstrate that the V-type ATPase, a necessary component of vesicle formation and trafficking, contributes to liver cell ATP release through effects on ATP uptake into vesicles.

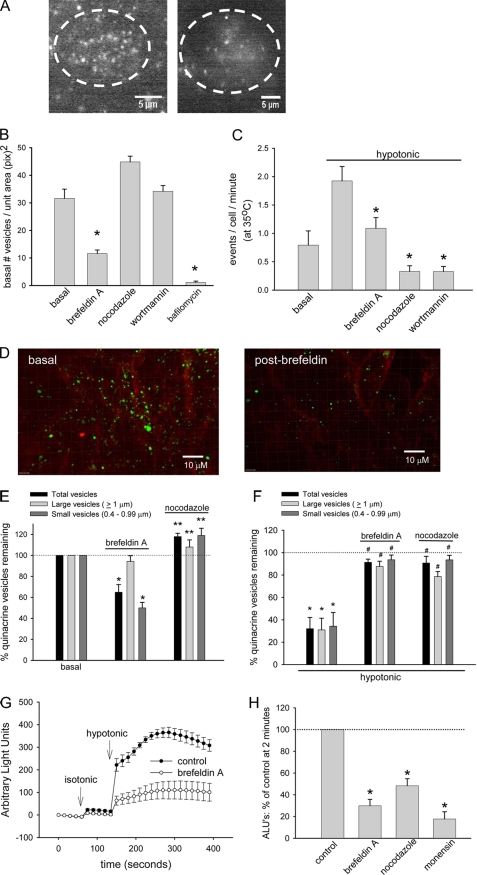

Regulation of Exocytosis and ATP Release

Previous studies using measurements of ATP in bulk solution suggest that volume-sensitive exocytosis and ATP release is potentiated by protein kinase C (16) and requires intact phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling (6). If the vesicles visualized by quinacrine play a role in this process, then parallel regulation of exocytosis and ATP release would be anticipated. The strategy for addressing this possibility is shown in Fig. 5. First, following exposure of cells to brefeldin A (4–6 h), an inhibitor of protein translocation through the Golgi, cells were exposed to quinacrine to label vesicles and imaged by TIRF microscopy. Brefeldin exposure decreased the number of quinacrine-stained vesicles under basal conditions (11.61 ± 1.28 vesicles/unit area (square pixels)) versus control (31.62 ± 3.35 vesicles/unit area (square pixels)), suggesting depletion of the submembrane pool in question (Fig. 5A). Studies utilizing digital reconstruction of spinning disk confocal z-stacks demonstrated a similar loss of the cellular pool of quinacrine-stained vesicles after brefeldin (decrease of 35.1 ± 7.3% from basal, n = 11, p < 0.01 (Fig. 5, D and E)). Interestingly, the effect was most pronounced on the pool of small (<1-μm) vesicles (decrease of 50.1 ± 5.3% from basal, n = 11, p < 0.01). Dynamic confocal imaging after hypotonic exposure revealed that brefeldin significantly inhibited the normal loss of quinacrine-stained vesicles observed in control cells (decrease of only 8.7 ± 2.8% versus 67.9 ± 10.1% of total vesicles, n = 11, p < 0.01 (Fig. 5F)). In parallel, the dynamics of ATP release in bulk solution were measured using luminometry (integrated signal from >106 cells/plate (Fig. 5, G and H)). Under control conditions, the addition of isotonic solution as a control for mechanical stimulation caused a small increase in detectable ATP (from 1.22 ± 0.15 to 22.8 ± 4.9 ALU), whereas exposure to the same volume of hypotonic solution to increase cell volume caused a much greater release (365.7 ± 23.2 ALU at 2 min, n = 9, p < 0.05) as described previously (6). Preincubation with brefeldin A using conditions sufficient to deplete quinacrine staining inhibited the response to isotonic (8.4 ± 3.1 ALU, n = 9, p < 0.05) and hypotonic exposure (110.3 ± 39.4 ALU, n = 9, p < 0.05, Fig. 5, G and H).

FIGURE 5.

Regulation of exocytosis and ATP release. A, representative TIRF image of the submembrane space of a single HTC cell, labeled with quinacrine according to protocol, during control conditions and after incubation with brefeldin A (10 μm for 1 h). B, cumulative data demonstrating basal number of vesicles in submembrane space visualized by TIRF. Incubation with brefeldin A (n = 21) or bafilomycin A1 (4 μm × 30 min, n = 8) significantly decreased the basal number of vesicles. *, p < 0.01 versus basal (n = 21). Nocodazole (n = 25) or wortmannin (n = 30) did not affect basal number of vesicles in submembrane space. C, cumulative data demonstrating number of exocytic events/cell/min during basal conditions and after hypotonic exposure (33% decrease osmolality) during TIRF. Incubation with brefeldin A (10 μm, n = 13), nocodazole (10 μm, n = 25), or wortmannin (50 nm, n = 30) significantly inhibited the number of exocytic events. *, p < 0.01 compared with control (n = 21). D, representative confocal images of confluent HTC cells dually labeled with FM4-64 and quinacrine according to the protocol shown in Fig. 3. Incubation with brefeldin A (10 μm × 1 h) decreased the number of quinacrine-stained vesicles. E, cumulative data demonstrating basal number of vesicles as visualized by confocal microscopy and quantified by a computer algorithm described in the legend to Fig. 3. Incubation with brefeldin A significantly decreased the number of total (black bar) and small (dark gray bar) vesicles (*, p < 0.01 versus basal) but had little effect on large vesicles (n = 11). Incubation with nocodazole (10 μm × 15 min) increased the basal number of vesicles. **, p < 0.05 versus basal (n = 10). F, cumulative data demonstrating number of vesicles remaining after hypotonic exposure. *, p < 0.01 versus basal. Both brefeldin A (n = 11) and nocodazole (n = 10) significantly inhibit the loss of quinacrine-stained vesicles. #, p < 0.05 versus hypotonic control (n = 11). G, bulk ATP release (arbitrary light units) was measured from confluent HTC cells after isotonic and hypotonic (33%) exposures in control (black circles) or after incubation with brefeldin A (open circles). Each point represents mean ± S.E. (n = 6 each). H, cumulative data demonstrating effect of inhibitors of vesicle formation and trafficking on bulk ATP release. Values represent percentage of maximal control ATP release at 2 min. Brefeldin A, nocodazole, and monensin (100 μm) significantly inhibited ATP release in response to hypotonic exposure. *, p < 0.05 versus control, n = 5–6 each.

Using a similar approach, the effects on quinacrine vesicles of inhibitors of vesicular formation and trafficking were assessed by TIRF and confocal microscopy and compared with parallel studies of ATP release to develop insights into the signaling events important to ATP release. Preincubation with nocodazole (10 μm for 15 min), a microtubule-depolymerizing agent; or wortmannin (50 nm for 15 min), an inhibitor of phosphoinositide 3-kinase, each inhibited the volume-stimulated exocytic response seen under control conditions (increase of fluorescence events/cell/min (Fig. 5C)). This inhibition could not be explained by a decrease in the basal number of vesicles per unit area (Fig. 5B). In parallel, these same agents decreased volume-sensitive ATP release as well (Fig. 5H). Similarly, the carboxylic ionophore monensin, which is known to dissipate the transmembrane pH gradients in Golgi and lysosomal compartments, inhibited volume-stimulated ATP release from cell monolayers (Fig. 5H). Thus, quinacrine appears to be a good marker for ATP-containing vesicles, and there is close correlation between exocytic events as visualized by TIRF microscopy, total vesicle counts by spinning disk confocal microscopy, and measurement of ATP in solution. Further, intact mechanisms for vesicle formation, acidification, and trafficking are required for volume-sensitive ATP release.

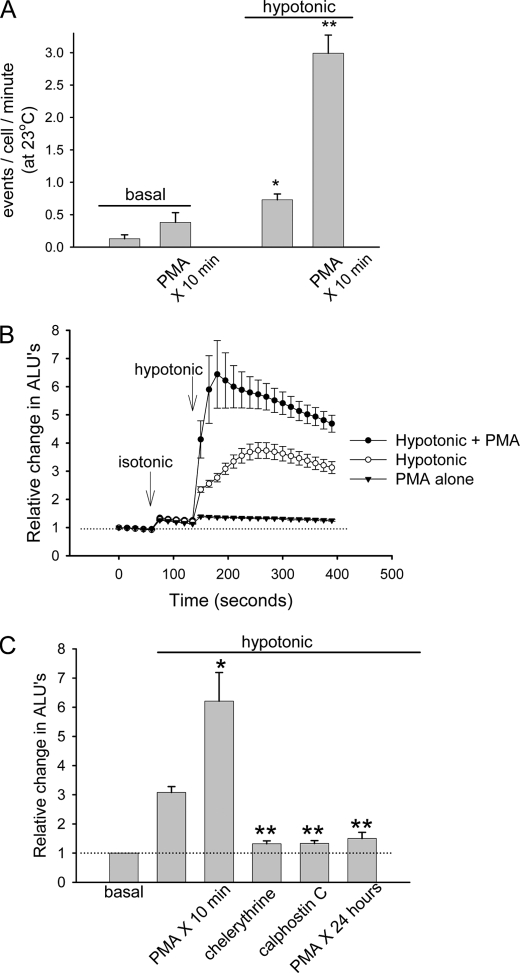

Regulation of Exocytosis by Protein Kinase C (PKC)

Increases in liver cell volume result in activation of phorbol-sensitive PKC isoforms, which in turn serve as a regulatory signal leading to volume-sensitive exocytosis and ATP release (16). In order to characterize the relationship between the quinacrine-enriched vesicles demonstrated herein and the more generalized exocytosis visualized by FM1-43, cells were loaded with quinacrine and again visualized by TIRF microscopy (Fig. 6), and the effects of PKC signaling were assessed. Prior exposure to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) to activate protein kinase C stimulated volume-sensitive (33% hypotonicity) exocytosis (2.99 ± 0.28 events/cell/min, n = 28) rates ∼4-fold above control (0.73 ± 0.09 events/cell/min, n = 35, p < 0.05 (Fig. 6A)). In parallel studies, exposure to PMA alone had no effect on basal ATP release but enhanced significantly the amount of ATP released following hypotonic exposure (relative change of 6.43 ± 1.2 ALU versus 3.73 ± 0.28 ALU in control cells, n = 5, p < 0.05 (Fig. 6B)). In other studies, inhibition of PKC by chelerythrine, calphostin C, or prolonged incubation with PMA (24 h) all inhibited significantly volume-sensitive ATP release (1.32 ± 0.10, 1.33 ± 0.09, 1.5 ± 0.21 ALU, respectively, versus 3.08 ± 0.21 ALU in control cells, n = 5–8 each, p < 0.05 for each (Fig. 6C)) as described for Mz-ChA-1 biliary cells (16). Thus, activation of PKC alone is not sufficient to stimulate detectable ATP release but potentiates the exocytic response to hypotonic exposure in a manner consistent with recruitment of a volume-sensitive pool of ATP-containing vesicles to a readily releasable state.

FIGURE 6.

Regulation of exocytosis and ATP release by PKC. A, HTC cells were labeled with quinacrine and imaged via TIRF microscopy according to the protocol in Fig. 2 at 23 °C. Cumulative data represent the number of exocytic events/cell/min. Incubation with PMA (1 μm × 10 min, n = 28) significantly increased the number of hypotonic buffer-stimulated (33% decrease in osmolality) exocytic events versus control (n = 35). *, p < 0.01 versus basal without PMA; **, p < 0.05 versus hypotonic control. B, bulk ATP release (arbitrary light units) was measured from confluent HTC cells after isotonic and hypotonic (33%) exposures in control (open circles) or after incubation with PMA (closed circles). Filled triangles, isotonic exposure followed by PMA exposure (without hypotonic exposure). Each point represents mean ± S.E. (n = 5 trials each). C, cumulative data demonstrating effects of PKC stimulation (PMA 1 μm × 10 min) or inhibition by chelerythrine (20 μm × 15 min), calphostin C (3 μm × 15 min), or PMA (1 μm × 24 h) on hypotonic buffer-stimulated ATP release. Data represent mean ± S.E. of maximal ATP release (n = 5–8 for each). *, hypotonic buffer-stimulated ATP release was significantly increased by PMA, p < 0.05 versus hypotonic control; **, hypotonic buffer-stimulated ATP release was significantly decreased by inhibition of PKC, p < 0.05 versus hypotonic control.

DISCUSSION

Although essentially all epithelia are capable of physiologic ATP release, definition of the mechanisms involved has proven to be challenging (7). The principal findings of these studies in a liver cell line are that (i) ATP release is not uniform but reflects point source release by a defined subset of cells; (ii) ATP within cells is localized to discrete zones of high intensity that are ∼1 μm in diameter, suggesting a vesicular localization; (iii) these vesicles originate from a bafilomycin A1-sensitive pool, are depleted by hypotonic exposure, and are not rapidly replenished from recycling of endocytic vesicles; and (iv) exocytosis of quinacrine-labeled vesicles in response to cell volume depends upon a complex series of signaling events that requires intact microtubules as well as PI-3 kinase and protein kinase C. Collectively, these findings are most consistent with an essential role for exocytosis in regulated release of ATP and initiation of purinergic signaling in liver cells. They do not, however, rule out the possibility that exocytosis is involved in trafficking of ATP-permeable channels as well.

Following the demonstration of ATP-containing vesicles in astrocytes, evidence has emerged to suggest that epithelial ATP release might also be related, at least in part, to exocytosis. Brefeldin A, which blocks trafficking between endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi, impairs ATP release in oocytes (33) and urogenital epithelium (34), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling in liver and Rho kinase and tyrosine kinase signaling in aortic endothelia are required for ATP release (17, 35). Both pathways are implicated in the regulation of cytoskeletal reorganization and vesicular trafficking. Finally, despite tantalizing clues to the contrary, it has been difficult to fully support direct roles for CFTR or MDR as ATP channels involved in the physiological release of ATP (reviewed in Ref. 7), despite the fact that these proteins are expressed in liver tissues.

Recently, a vesicular nucleotide transporter, SLC17A9, has been identified in humans and mice and appears to play an essential role in vesicular storage of ATP in ATP-secreting cells (36). Of relevance to the current studies, SLC17A9 localized to chromaffin granules, granules that represent the quinacrine-enriched fraction in adrenal tissues and store ATP (30, 37–40). These exciting studies provide further evidence of vesicular ATP storage and release in ATP-secreting cells and may provide a potential molecular target to modulate purinergic signaling pathways. The potential role of this protein in liver cell ATP release deserves future exploration.

In the current studies, increases in cell volume stimulated abrupt point source bursts of ATP as detected by bioluminescence. These focal zones expanded radially to ∼200 μm and then disappeared with a t½ of 4.9 s. Notably, the majority of cells failed to release ATP despite the fact that they were subject to the same increases in relative volume. This result was surprising given the apparent uniformity of hepatocytes in vivo. However, the findings appear analogous to real-time bioluminescence detection of ATP release from astrocytes stimulated by lowering extracellular calcium (10). In those studies, ATP appeared to emanate from a single cell, and connexin 43 overexpression increased ATP burst frequency, although the authors were careful to point out that this was not necessarily a result of ATP efflux through connexin hemichannels (10). Similar ATP burst kinetics were also detected using HUVEC and human bronchial epithelial cells, where the radial diffusion of extracellular ATP averaged 82–181 μm in diameter (10). Although the temporal and spatial scale of ATP bioluminescence is compatible with known roles in hepatic signaling, the lack of uniformity in ATP release across the field raises interesting questions regarding the potential presence of specialized cells or specialized conditions that generate such focal responses.

Dynamic viewing of the submembrane space of living cells with TIRF microscopy revealed a population of quinacrine-enriched vesicles that underwent fusion and release of their contents upon cell swelling. Notably, quinacrine is concentrated within ATP-containing vesicles (13, 41, 42). The pattern of distribution of quinacrine fluorescence revealed multiple (often >40 per cell) regions of high intensity consistent with a predominant vesicular localization. Under control conditions, these showed spontaneous three-dimensional Brownian type motion and a low rate of spontaneous exocytosis. Hypotonic exposure in amounts sufficient to increase bulk extracellular ATP increased the observed frequency of exocytic events ∼5-fold and decreased the number of quinacrine-labeled vesicles to ∼20% of initial values.

Several additional observations support the conclusion that vesicular release of ATP is probably related to the observed increase in extracellular ATP concentrations. First, both constitutive and volume-stimulated release were temperature-sensitive, consistent with an exocytic mechanism (43). Second, the number of ATP vesicles and the amount of ATP released were inhibited by incubation with bafilomycin or brefeldin A to inhibit vesicular acidification or trafficking, respectively (33, 34, 40). Third, intact microtubules and phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling are required for both vesicular exocytosis and ATP release. These conclusions are strengthened by the combined use of several modalities at different distance scales showing parallel regulation of exocytosis and ATP release. It is acknowledged that in bioluminescence studies, the point source pattern of ATP bioluminescence could result from channel-mediated ATP release, exocytosis of ATP containing vesicles, or exocytosis of ATP-permeable channels. Although the current studies do not resolve the molecular basis of ATP transport, they do support the conclusions that ATP is concentrated within vesicles and that intact exocytic mechanisms are required for volume-stimulated ATP release.

These findings are of interest in view of the recent identification of a volume-sensitive pool of vesicles in different liver cell models. Biliary cells, for example, possess a dense population of vesicles ∼140 nm in diameter in the subapical space (44), and increases in cell volume increase the rate of exocytosis ∼10-fold to values sufficient to replace 15–30% of plasma membrane surface area within minutes through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent mechanism (16). Both the rate of exocytosis and the amount of ATP released are potentiated by prior activation of PKC, suggesting that PKC is involved in the recruitment of these vesicles to a readily releasable state (16). These present observations support an analogous paradigm. Specifically, acute exposure to PMA to activate PKC had small effects on the rate of exocytosis of quinacrine-stained vesicles and no effect on the appearance of ATP in solution, indicating that activation of ATP alone is not sufficient to activate the full response. However, prior exposure to PMA greatly increased the response to hypotonic exposure as assessed by TIRF microscopy of quinacrine vesicles and measurement of ATP in solution. These observations suggest that PKC serves to prime a pool of ATP-containing vesicles, converting them from a nonreleasable to a readily releasable state, although there is no direct morphological evidence to support this conclusion (16).

In summary, in this model liver cell, increases in cell volume stimulate exocytosis of a pool of vesicles enriched in ATP. The localized increase in extracellular ATP concentrations appears rapidly and extends over ∼10 cell diameters, and within seconds, concentrations fall below detectable levels. The findings support a model wherein vesicular exocytosis is closely regulated to modulate the concentrations of ATP outside the cell in response to changing physiological demands. Moreover, because ATP can be metabolized into other purinergic agonists and liver cells express an array of purinergic receptor subtypes, regulation of ATP availability is likely to play important roles in a range of liver cell and organ functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

TIRF, spinning disk confocal imaging, and three-dimensional volume rendering measurements were carried out in the University of Texas Southwestern Live Cell Imaging Facility.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIDDK, Grants DK078587 (to A. P. F.), DK43278, and DK46082 (to J. G. F.). This study was also supported by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (FERANC08G0) and the Children's Medical Center Foundation.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- L-L

- luciferin-luciferase

- TIRF

- total internal reflection fluorescence

- LDH

- lactate dehydrogenase

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- PMA

- phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schlosser S. F., Burgstahler A. D., Nathanson M. H. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 9948–9953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Roman R., Lidofsky S. D., Fitz J. G. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 12020–12025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minagawa N., Nagata J., Shibao K., Masyuk A. I., Gomes D. A., Rodrigues M. A., Lesage G., Akiba Y., Kaunitz J. D., Ehrlich B. E., Larusso N. F., Nathanson M. H. (2007) Gastroenterology 133, 1592–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman R. M., Feranchak A. P., Salter K. D., Wang Y., Fitz J. G. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 276, G1391–G1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feranchak A. P., Fitz J. G. (2007) Gastroenterology 133, 1726–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feranchak A. P., Roman R. M., Schwiebert E. M., Fitz J. G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14906–14911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazarowski E. R., Boucher R. C., Harden T. K. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64, 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schock S. C., Leblanc D., Hakim A. M., Thompson C. S. (2008) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 368, 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suadicani S. O., Brosnan C. F., Scemes E. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 1378–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arcuino G., Lin J. H., Takano T., Liu C., Jiang L., Gao Q., Kang J., Nedergaard M. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 9840–9845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carabelli V., Carra I., Carbone E. (1998) Neuron 20, 1255–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodin P., Burnstock G. (2001) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 38, 900–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorensen C. E., Novak I. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 32925–32932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roman R. M., Lomri N., Braunstein G., Feranchak A. P., Simeoni L. A., Davison A. K., Mechetner E., Schwiebert E. M., Fitz J. G. (2001) J. Membr. Biol. 183, 165–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunstein G. M., Roman R. M., Clancy J. P., Kudlow B. A., Taylor A. L., Shylonsky V. G., Jovov B., Peter K., Jilling T., Ismailov I. I., Benos D. J., Schwiebert L. M., Fitz J. G., Schwiebert E. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6621–6630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gatof D., Kilic G., Fitz J. G. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 286, G538–G546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feranchak A. P., Roman R. M., Doctor R. B., Salter K. D., Toker A., Fitz J. G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30979–30986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roman R. M., Smith R. L., Feranchak A. P., Clayton G. H., Doctor R. B., Fitz J. G. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 280, G344–G353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodily K., Wang Y., Roman R., Sostman A., Fitz J. G. (1997) Hepatology 25, 403–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor A. L., Kudlow B. A., Marrs K. L., Gruenert D. C., Guggino W. B., Schwiebert E. M. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 275, C1391–C1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo K., Dutta A. K., Patel V., Kresge C., Feranchak A. P. (2008) J. Physiol 586, 2779–2798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda I., Shinoda F., Kamaya H. (1994) Biophys. J. 66, 2107–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soesbe T. C., Lewis M. A., Richer E., Slavine N. V., Antich P. P. (2007) IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 54, 1516–1524 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller B., Barrett H., Barber B., Wilson D. (2007) J. Nucl. Med. 48, Suppl. 2, 47P [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell C. H., Carré D. A., McGlinn A. M., Stone R. A., Civan M. M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7174–7178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White P. N., Thorne P. R., Housley G. D., Mockett B., Billett T. E., Burnstock G. (1995) Hear. Res. 90, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alund M., Olson L. (1979) Brain Res. 166, 121–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coco S., Calegari F., Pravettoni E., Pozzi D., Taverna E., Rosa P., Matteoli M., Verderio C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1354–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axelrod D. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 361, 1–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steyer J. A., Almers W. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 268–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feranchak A. P., Fitz J. G., Roman R. M. (2000) J. Hepatol. 33, 174–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuboi T., Zhao C., Terakawa S., Rutter G. A. (2000) Curr. Biol. 10, 1307–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maroto R., Hamill O. P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 23867–23872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knight G. E., Bodin P., De Groat W. C., Burnstock G. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 282, F281–F288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koyama T., Oike M., Ito Y. (2001) J. Physiol. 532, 759–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sawada K., Echigo N., Juge N., Miyaji T., Otsuka M., Omote H., Yamamoto A., Moriyama Y. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5683–5686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camacho M., Machado J. D., Montesinos M. S., Criado M., Borges R. (2006) J. Neurochem. 96, 324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Painter G. R., Diliberto E. J., Jr., Knoth J. (1989) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86, 2239–2242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa J. L., Sokoloski E. A., Morris S. J. (1984) Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 45, 389–398 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bankston L. A., Guidotti G. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 17132–17138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pangrsic T., Potokar M., Stenovec M., Kreft M., Fabbretti E., Nistri A., Pryazhnikov E., Khiroug L., Giniatullin R., Zorec R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 28749–28758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pryazhnikov E., Khiroug L. (2008) Glia 56, 38–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boudreault F., Grygorczyk R. (2004) J. Physiol. 561, 499–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doctor R. B., Dahl R., Fouassier L., Kilic G., Fitz J. G. (2002) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C1042–C1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.