Abstract

Snake venoms are a mixture of pharmacologically active proteins and polypeptides that have led to the development of molecular probes and therapeutic agents. Here, we describe the structural and functional characterization of a novel neurotoxin, haditoxin, from the venom of Ophiophagus hannah (King cobra). Haditoxin exhibited novel pharmacology with antagonism toward muscle (αβγδ) and neuronal (α7, α3β2, and α4β2) nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) with highest affinity for α7-nAChRs. The high resolution (1.5 Å) crystal structure revealed haditoxin to be a homodimer, like κ-neurotoxins, which target neuronal α3β2- and α4β2-nAChRs. Interestingly however, the monomeric subunits of haditoxin were composed of a three-finger protein fold typical of curaremimetic short-chain α-neurotoxins. Biochemical studies confirmed that it existed as a non-covalent dimer species in solution. Its structural similarity to short-chain α-neurotoxins and κ-neurotoxins notwithstanding, haditoxin exhibited unique blockade of α7-nAChRs (IC50 180 nm), which is recognized by neither short-chain α-neurotoxins nor κ-neurotoxins. This is the first report of a dimeric short-chain α-neurotoxin interacting with neuronal α7-nAChRs as well as the first homodimeric three-finger toxin to interact with muscle nAChRs.

Keywords: Methods/X-ray Crystallography, Protein, Protein/Chemistry, Toxins, Neurotoxin, Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors, Snake Venom, Acetylcholine Receptor, Neurotoxin, Snake Venom

Introduction

Snake venoms are a rich source of pharmacologically active proteins and polypeptides targeting a variety of receptors with high affinity and specificity (1). Because of their high specificity, some of these molecules have contributed significantly (a) to the isolation and characterization of different receptors and their subtypes in the field of molecular pharmacology and (b) as lead compounds in the development of therapeutic agents (2, 3). For example, the discovery of α-bungarotoxin, a postsynaptic neurotoxin from the venom of Bungarus multicinctus, led to the identification of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR),3 the first isolated receptor protein (4) as well as the first one to be characterized electrophysiologically (5) and biochemically (6, 7). Subsequently, it was also used to characterize several other nAChRs (8–10).

Snake venom proteins can be broadly classified as enzymatic and non-enzymatic proteins. Three-finger toxins (3FTxs) are the largest group of non-enzymatic snake venom proteins (1, 11). They are most commonly found in the venoms of elapid and hydrophiid snakes. Recently, our laboratory has also demonstrated the presence of 3FTxs from colubrid venoms (12, 13), and 3FTx transcripts have been found in the venom gland transcriptome of viperid snakes (14, 15). The proteins in this family of toxins share a common structural scaffold of three β-sheeted loops emerging from a central core (11, 16). Despite the overall similarity in structure, these proteins have diverse functional properties. Members of this family include neurotoxins targeting the cholinergic system (7, 11, 16), cytotoxins/cardiotoxins interacting with the cell membranes (17), calciseptine and related toxins that block the L-type Ca2+ channels (18), dendroaspins, which are antagonists of various cell adhesion processes (19), and β-cardiotoxin antagonizing the β-adrenoceptors (20). The subtle variations in their structures, such as the presence of extra disulfide bonds, differences in size and overall conformation (twists and turns) of the loops, and longer C-terminal and/or N-terminal extensions (21), may contribute to the observed functional diversity as well as specificity of these toxins (22).

This family contains several types of neurotoxins that interact with different subtypes of nicotinic and muscarinic receptors involved in central and peripheral cholinergic transmission. Depending on the target receptors, these neurotoxins can be broadly divided into various groups. Curaremimetic or α-neurotoxins that target muscle (αβγδ or α1 subtype) nAChRs (7, 16, 23) belong to short-chain and long-chain neurotoxins (classified based on size and number of disulfide bridges (24)). Long-chain neurotoxins, but not short-chain neurotoxins, also target neuronal α7-nAChRs associated with neurotransmission in the brain (25). κ-Neurotoxins, such as κ-bungarotoxin (B. multicinctus), show specificity for other neuronal subtypes, α3β2- and α4β2-nAChRs (26, 27). Muscarinic 3FTxs, unlike many small molecule ligands, can distinguish between different types of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) (for review, see Ref. 28) and hence are useful in the characterization of these receptor subtypes. Muscarinic toxin 1, isolated from the venom of Dendroaspis angusticeps, interacts with mAChR subtype 1 (M1) (29), whereas muscarinic toxin 3 (MT3), isolated from the same snake, interacts with M4 mAChRs (30). In recent years, new 3FTxs with distinct and novel receptor specificities have been characterized and added to this growing library (12, 13, 31–36), justifying their usefulness as pharmacological tools to dissect the cholinergic circuitry to understand the role of individual receptor subtypes or offer clues to the rational design of specific therapeutics.

All neurotoxins characterized to date exist as monomers with the exception of κ-neurotoxins from Bungarus sp. (37, 38), which is a non-covalently linked homodimer that binds neuronal (α3β2 and α4β2) but not muscle (αβγδ) nAChRs. More recently, we published the first report of a covalent heterodimeric neurotoxin, irditoxin from the venom of Boiga sp., which was a uniquely irreversible inhibitor of muscle (αβγδ) nAChRs (13). Here, we report the purification, pharmacological characterization, and a high resolution crystal structure of a novel non-covalent homodimeric neurotoxin from the venom of Ophiophagus hannah (King cobra). Although its quaternary structure is similar to κ-neurotoxins, it exhibited novel pharmacology with potent blocking activity on muscle (αβγδ) as well as neuronal (α7, α3β2, and α4β2) nAChRs. Based on the high resolution crystal structure (1.55 Å) we have explored its structural similarities with other neurotoxins. This new toxin was named haditoxin (O. hannah dimeric neurotoxin) and is the first homodimeric three-finger neurotoxin interacting with α1-nAChRs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Lyophilized O. hannah venom was obtained from PT Venom Indo Persada (Jakarta, Indonesia) and Kentucky Reptile Zoo (Slade, KY). Reagents for N-terminal sequencing by Edman degradation are from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). KCl, acetonitrile, and trifluoroacetic acid were from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. Precision Plus protein standards, dual color (marker for SDS-PAGE), and bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate (BS3) were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories and Pierce, respectively. Superdex 30 HiLoad (16/60) column and Jupiter C18 (5 μ, 300 Å, 4.6 × 150 mm) were purchased from GE Healthcare and Phenomenex (Torrance, CA), respectively. Crystal screening solution and accessories were obtained from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, CA). All other chemicals including α-bungarotoxin from B. multicinctus were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All the reagents were of the highest purity grade. Water was purified using a MilliQ system (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Animals

Animals (Swiss albino mice and Sprague-Dawley rats) were acquired from the National University of Singapore Laboratory Animal Center and acclimatized to the Department Animal Holding Unit for at least 3 days before the experiments. They were housed, four per cage, with food and water available ad libitum in a light controlled room (12-h light/dark cycle, light on at 7:00 a.m.) at 23 °C and 60% relative humidity. Domestic chicks (Gallus gallus domesticus) were purchased from Chew's Agricultural Farm, Singapore, and delivered on the day of experimentation. Animals were sacrificed by exposure to 100% carbon dioxide. All experiments were conducted according to the Protocol (021/07a) approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National University of Singapore.

Purification of the Protein

O. hannah crude venom (100 mg dissolved in 1 ml of MilliQ water and filtered) was loaded onto a Superdex 30 gel filtration column, equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer; pH 7.4, and eluted with the same buffer using an ÄKTA purifier system (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the toxin of interest were further subfractionated by reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a Jupiter C18 column, equilibrated with 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid, and eluted with a linear gradient of 80% (v/v) acetonitrile in 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. Elution was monitored at 280 and 215 nm. Fractions were directly injected into an API-300 liquid chromatography-tandem MS system (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) to determine the mass and homogeneity of the protein as described previously (20). Analyte software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) was used to analyze and deconvolute the raw mass data. Fractions showing the expected molecular mass were pooled and lyophilized.

Capillary Electrophoresis

Capillary electrophoresis was performed on a BioFocus3000 system (Bio-Rad) to determine the homogeneity of the protein after RP-HPLC. The native protein (1 μg/μl) was injected to a 25 μm × 17 cm coated capillary using a pressure mode (5 p.s.i./s) and run in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) under 18 kV at 20 °C for 7 min. The migration was monitored at 200 nm.

N-terminal Sequencing

N-terminal sequencing of the native protein was performed by automated Edman degradation using a Procise 494 pulsed liquid-phase protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems) with an on-line 785A phenylthiohydantoin derivative analyzer. The phenylthiohydantoin amino acids were sequentially identified by mapping the respective separation profiles with the standard chromatogram.

CD Spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra (260–190 nm) were recorded using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco Corp., Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (20). The protein samples (concentration range 0.25–1 mg/ml) were dissolved in MilliQ water.

In Vivo Toxicity Study

Native protein (200 μl dissolved in 0.89% NaCl) was injected intraperitoneally using a 27-gauge 0.5-inch needle (BD Biosciences) into male Swiss albino mice (15 ± 2 g) at doses of 5, 10, and 25 mg/kg (n = 2). The symptoms of envenomation were observed, and in the event of death, the time of death was noted. The control group was injected with 200 μl of 0.89% NaCl. Postmortem examinations were conducted on all animals.

Ex Vivo Organ Bath Studies

Isolated tissue experiments were performed as described previously (13, 31) using a conventional organ bath (6 ml) containing Krebs solution of the following composition (in mm): 118 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 25 NaHCO3, 2.4 MgSO4, and 11 d-(+)glucose); pH 7.4, at 37 °C. This is continuously aerated with carbogen (5% carbon dioxide in oxygen). The resting tension of the tissues was maintained at 1–2 g, and the preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 30–45 min. Electrical field stimulation was carried out through platinum ring electrodes using a Grass stimulator S88 (Grass Instruments, West Warwick, RI). The magnitude of the contractile response was measured in gram tension. Data were continuously recorded on PowerLab/Chart 5 data acquisition system via a force displacement transducer (Model MLT0201) (AD Instruments, Bella Vista NSW, Australia). Neuromuscular blockade produced by a toxin is expressed as a percentage of the original twitch height in the absence of exposure to toxin. Dose-response curves representing the percent blockade after 30 min of exposure to the respective toxins were plotted.

Chick Biventer Cervicis Muscle (CBCM) Preparations

The CBCM nerve-skeletal muscle preparation (39) was isolated from chicks (6 days old) and mounted in the organ bath chamber under similar experimental conditions as described previously (12, 31). The effect of haditoxin (0.05–5 μm; n = 3) or α-bungarotoxin (0.01–1.0 μm; n = 3) on nerve-evoked twitch responses of the CBCM were studied. In separate experiments, the recovery from complete neuromuscular blockade was assessed by washing out the toxin with Krebs solution at 30-min intervals (three cycles of 30-s on pulse, 30-s off pulse) over a 120-min period.

Rat Hemidiaphragm Muscle (RHD) Preparations

The RHD muscle associated with the phrenic nerve (40) was isolated and mounted in a 5-ml organ bath chamber under similar conditions as stated for CBCM, as described previously (13). The effects of haditoxin (0.15–15 μm; n = 3) or α-bungarotoxin (0.01–1.0 μm; n = 3) on nerve-evoked twitch responses of the RHD were investigated. Recovery of neuromuscular blockade was assessed similarly as described above for CBCM.

Electrophysiology

Two-electrode voltage clamp experiments were done using Xenopus oocytes. The oocytes were prepared and injected as described by Hogg et al. (41). Briefly, 2 ng of cDNA encoding for human α4β2-, αβδϵ-, α7-, and α3β2-nAChRs were injected into the oocytes. Two-electrode voltage clamp measurements were done 2–3 days after injection. During recordings, the oocytes were perfused with OR2 (oocyte ringer) containing (in mm): 82.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 Ca2Cl, 5 HEPES, and 20 μg/ml bovine serum albumin; pH 7.4. Atropine (0.5 μm) was added to all solutions to block activity of endogenous muscarinic receptors. Just before use, acetylcholine (ACh) and haditoxin were dissolved the OR2 solution. All recordings were performed with an automated two-electrode voltage clamp robot. Oocytes were clamped at −100 mV, and data were digitized and analyzed off-line using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA).

Gel Filtration Chromatography

The oligomeric states of the protein were examined by gel filtration chromatography on a Superdex 75 column (1 × 30 cm) equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) using an ÄKTA purifier system at a flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. Calibration was done using bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), cytochrome c (12.4 kDa), aprotinin (6.5 kDa), and blue dextran (200 kDa) as molecular mass markers. Native protein (0.25–10 μm) as well as samples (0.25–10 μm) treated with 0.6% SDS (2 h of incubation at room temperature) (37) were loaded separately onto the column, and respective elution profiles were recorded. For the SDS-treated samples, the column was equilibrated with the same buffer containing 0.1% SDS.

Electrophoresis

Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE of the protein of interest in the presence or absence of cross-linker BS3 (42) was performed on a 12% gel, under reducing conditions, using the Bio-Rad Mini-Protean II electrophoresis system. The concentration of BS3 used was 5 mm. The protein bands were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

Crystallization and Data Collection

Crystallization conditions for the protein were screened with Hampton Research screens using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Lyophilized protein was dissolved in 10 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, with 100 mm NaCl. Crystallization experiments were performed at room temperature 297 K (24 °C) with drops containing equal volumes (1 μl) of reservoir and protein solution. Small rod-shaped crystals were formed within 2–3 days and grew to diffraction quality after 3 weeks. They were briefly soaked in the reservoir solution supplemented with 10% glycerol as cryo-protectant prior to the x-ray diffraction data collection. Then these were flash-frozen in a nitrogen cold stream at 100 K (−173 °C). Diffraction up to 1.55 Å was obtained using a CCD detector (Platinum135) mounted on a Bruker Microstar Ultra rotating anode generator (Bruker AXS, Madison, WI). A complete data set was collected, processed, and scaled using the program HKL2000 (43).

RESULTS

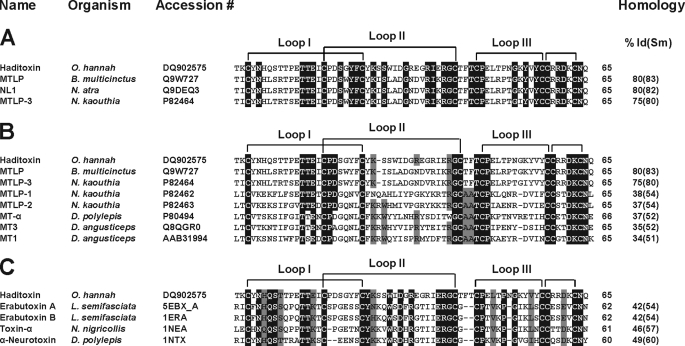

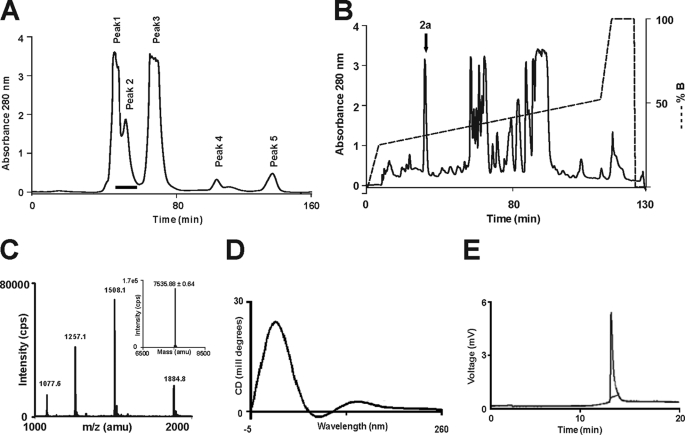

Five novel 3FTxs were identified from the cDNA library of the venom gland tissue of O. hannah, and one of them, named β-cardiotoxin, has been characterized previously (20). Here, we describe the characterization of the second novel toxin, identified previously as an MTLP-3 homolog based on sequence homology (20) (Fig. 1). The liquid chromatography/MS profile of O. hannah venom (44) showed the presence of a 7,535.67 ± 0.60 Da protein, similar to the expected molecular mass of the protein being characterized. This protein was purified from the crude venom using a two-step chromatographic approach. Firstly, the venom components were separated based on their sizes into five peaks using gel filtration chromatography (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, each peak was fractionated by RP-HPLC, and the fractions were analyzed by ESI-MS to identify the presence of the protein of interest (Fig. 2A, black bar). Further, these fractions were pooled and separated by RP-HPLC (Fig. 2B). The ESI-MS of fraction 2a (Fig. 2C, black arrow) showed three peaks with mass/charge (m/z) ratios ranging from +4 to +6 charges (Fig. 2C), and the final reconstructed mass spectrum showed a molecular mass of 7,535.67 ± 1.25 Da, which matched the calculated mass of 7,534.42 Da (Fig. 2C, inset). The secondary structural elements of haditoxin were analyzed using far-UV CD spectroscopy. The spectrum shows maxima at 230 and 198–200 nm and a minimum at 215 nm (Fig. 2D). Thus, haditoxin was found to be composed of β-sheeted structure similar to all other 3FTxs (11, 16). The presence of a single protein peak in the electropherogram (Fig. 2E) indicates the homogeneity of the protein, ensuring the absence of contaminants, especially other α-neurotoxin(s) and cytotoxins present in the venom. Identification was further confirmed by N-terminal sequencing of the first 36 residues, which matched the cDNA sequence of the MTLP-3 homolog (20). This protein was found to be a homodimer (see below) and hence was renamed as haditoxin (O. hannah dimeric neurotoxin) following the nomenclature of dimeric 3FTxs (12, 13).

FIGURE 1.

Multiple sequence alignment of novel proteins. A–C, sequence alignment of haditoxin with the most homologous sequences (A), muscarinic toxin homologs (B), and short-chain α-neurotoxins (C). Toxin names, species, and accession numbers are shown. Conserved residues in all sequences are highlighted in black. Disulfide bridges and loop regions are also shown. At the end of each sequence, the numbers of amino acids are stated. The homology (sequence identity and similarity (% Id(Sm))) of each protein is compared with haditoxin and shown at the end of each sequence. N. atra, Naja atra; N. kaouthia, Naja kaouthia; D. polylepis, Dendroaspis polylepis; and L. semifasciata, Laticauda semifasciata.

FIGURE 2.

Purification of haditoxin from the venom of O. hannah. A, gel filtration chromatogram of crude venom. Crude venom (100 mg/ml) was fractionated using a Superdex 30 HiLoad (16/60) column. The column was pre-equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). Proteins were eluted at a flow rate of 1 ml/min using the same buffer. A black bar at Peak 2 indicates the fractions containing haditoxin. B, RP-HPLC profile of the gel filtration fractions containing haditoxin. Jupiter C18 (5 μ, 300 Å, 4.5 × 250 mm) analytical column was equilibrated with 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid. Protein of interest was eluted from the column with a flow rate of 1 ml/min with a gradient of 23–49% buffer B (80% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid). The dotted line indicates the gradient of the buffer B. The downward arrow at Peak 2a indicates fractions containing haditoxin. C, ESI-MS profile of the RP-HPLC fraction containing haditoxin. The spectrum shows a series of multiply charged ions, corresponding to a single, homogenous peptide with a molecular mass of 7,535.88 Da. Inset, reconstructed mass spectrum of haditoxin; CPS = counts/s; amu = atomic mass units. D, far-UV CD spectrum of haditoxin. The protein was dissolved in MilliQ water (0.5 mg/ml), and the CD spectra were recorded using a 0.1-cm path length cuvette. E, electropherogram of haditoxin. The sample was injected using pressure mode 5 p.s.i./s, and electrophoresis runs were carried out using a coated capillary (17 cm × 25 μm) at 18 kV, with 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) at 20 °C for 7 min.

Investigation of Haditoxin for Muscarinic Effects

As detailed in Fig. 1, A and B, haditoxin showed high similarity (80–83%) with muscarinic toxin homologs (MTLP and MTLP-3) as well as similarity with muscarinic toxins (MT-α, MT7, and MT3) (51–52%). As such, we examined the effects of haditoxin on in vitro smooth muscle preparations, the rat ileum and rat anococcygeus muscle, pharmacologically characterized to represent M2 (45) and M3 mAChRs (46), respectively. In both preparations, the protein had no effect on the contractile response of the muscle to exogenously applied ACh or electrical field stimulation, suggesting that haditoxin does not interact with M2 and M3 mAChRs (supplemental Fig. 1). Therefore, it is likely that the observed sequence similarity with muscarinic toxin homologs is probably coincidental due to either phylogeny or structure, including the presence of the core disulfide bridges, and not the function. This merits further investigation, including electrophysiological studies and/or binding assays on other subtypes of mAChRs.

In Vivo Toxicity of Haditoxin

In preliminary experiments to observe the biological effects of haditoxin, all mice injected with the toxin (5, 10, and 25 mg/kg) showed typical symptoms of peripheral neurotoxicity, such as paralysis of hind limbs and labored breathing, and finally died, presumably due to respiratory paralysis (47, 48). The time of death was recorded for each animal, with the average calculated to be 94, 32.5, and 20 min, respectively, for the 5, 10, and 25 mg/kg doses. On postmortem, no gross changes in the internal organs, notably hemorrhage, were observed.

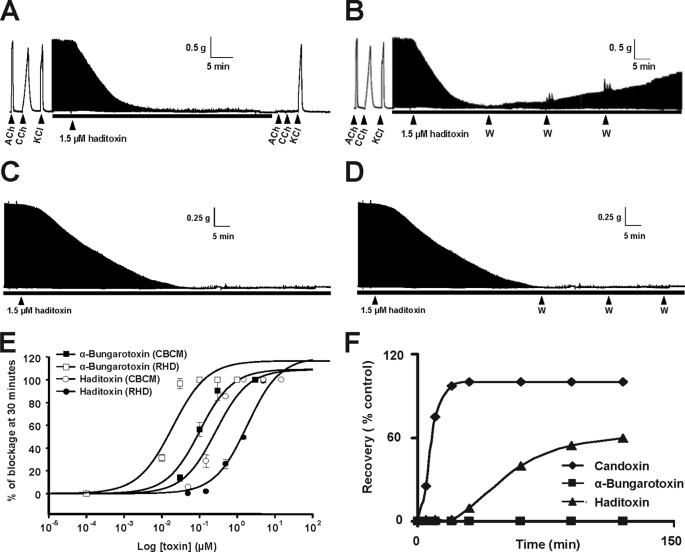

Ex Vivo Neurotoxic Effects of Haditoxin

The observed peripheral neurotoxic symptoms produced by haditoxin in vivo warranted detailed pharmacological characterization on neuromuscular transmission using CBCM and RHD preparations. Haditoxin (1.5 μm) produced a reproducible time- and dose-dependent neuromuscular blockade in both preparations (Fig. 3, A and C). In the CBCM, it completely inhibited the contractile response to exogenous agonists (ACh and carbachol (CCh)), whereas response to exogenous KCl and twitches evoked by direct muscle stimulation were not inhibited, indicating a postsynaptic neuromuscular blockade and an absence of direct myotoxicity.

FIGURE 3.

Pharmacological profile of haditoxin. A–D, a segment of tracing showing the effect of haditoxin (1.5 μm) on CBCM preparations (A), reversibility of CBCM preparation (B), RHD preparations (C), and reversibility of RHD preparation (D). Contractions were produced by exogenous ACh (300 μm), carbachol (CCh; 10 μm), and KCl (30 mm). The black bar indicates the electrical field stimulation. The point of washing out the toxin with Krebs solution in reversibility studies is indicated by the abbreviation W. E, dose-response curve of haditoxin and α-bungarotoxin on CBCM and RHD. The block is calculated as a percentage of the control twitch responses of the muscle to supramaximal nerve stimulation. Each data point is the mean ± S.E. of at least three experiments. F, comparative reversibility profile of α-bungarotoxin, haditoxin, and candoxin.

The IC50 of haditoxin on CBCM and RHD was 0.27 ± 0.07 and 1.85 ± 0.39 μm, respectively (Fig. 3E) (considering the fact that the protein exists as dimer in solution; see below). When compared with α-bungarotoxin (IC50 on CBCM 12.1 ± 5.4 nm and RHD 100.5 ± 22.5 nm) (Fig. 3E), haditoxin was about 50 times less potent on both avian (CBCM) and mammalian (RHD) neuromuscular junctions.

Reversibility of the neuromuscular blockade was tested for both preparations with intermittent washing (Fig. 3, D and F, black arrows). Partial recovery of the contractile response (60% recovery in 2 h) was observed in the CBCM (Fig. 3B) but not in the RHD (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that unlike typical α-neurotoxins such as α-bungarotoxin, haditoxin exhibits partial reversibility in action, at least in the CBCM.

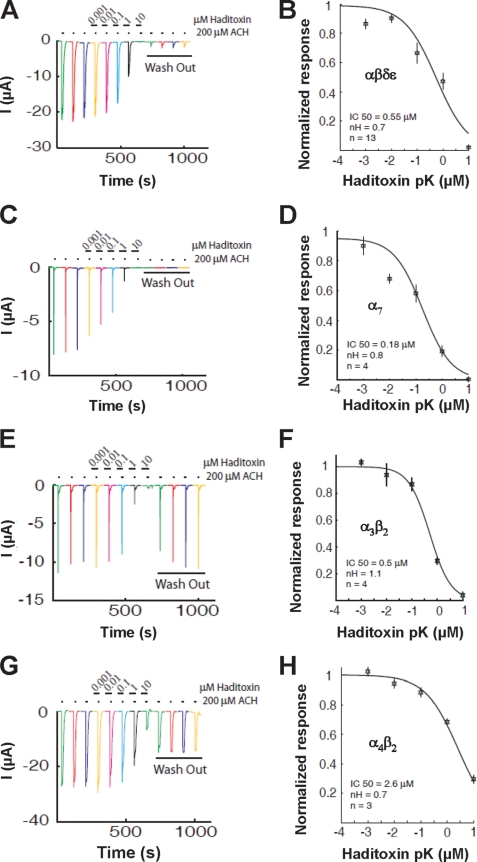

Effect of Haditoxin on Human nAChRs

Because haditoxin blocked the muscle activity of the CBCM and RHD, we examined its activity on human αβδϵ-nAChRs. Haditoxin completely inhibited the ACh-induced αβδϵ currents at a concentration of 10 μm (Fig. 4A) with an IC50 value of 550 nm (n = 13) (Fig. 4B). This inhibition was practically irreversible within 8 min of washout. This result is in good agreement with the findings on ex vivo studies with RHD as discussed earlier. Next, we tested the activity of haditoxin on α7- and α3β2-nAChRs. On α7-nAChRs, an irreversible block was observed at 10 μm concentration of haditoxin (Fig. 4C) with an IC50 value was 180 nm (n = 4) (Fig. 4D). As shown in Fig. 4E, 10 μm haditoxin fully blocked the response of α3β2-nAChRs, with an IC50 value of 500 nm (n = 4) (Fig. 4F). Notably, the blockade at α3β2 was fully reversible, whereas long-lasting blockade was observed at α7-nAChRs. This suggests that the KOff value at the α7 receptor is much smaller than at α3β2-nAChRs. As these two receptors display about equivalent IC50 values, this indicates that their respective KOn values are probably significantly different. However, the experimental protocol used herein prevents the detailed analysis of the KOn and KOff values. An additional difference between these two receptors resides in their structural composition. Although it is thought that α7-nAChRs display five identical ligand binding sites, only two binding sites are proposed for the α3β2-nAChRs. The difference in number of binding sites and effects on competitive blockade was previously discussed for α7- and α4β2-nAChRs, showing significant functional outcomes (49). Interestingly, haditoxin was almost 3-fold more potent to block ACh-induced responses mediated by α7-nAChRs (IC50 = 180 nm, n = 4) when compared with αβδϵ- and α3β2-nAChRs. There was no recovery after application of haditoxin. Finally, we tested the effect of haditoxin on α4β2-nAChRs. Application of 10 μm haditoxin blocked only 70% of the current with partial reversibility (Fig. 4G). The IC50 value of the blockade is in the micromolar range (IC50 = 2.6 μm, n = 3) (Fig. 4H). However, further experiments will be necessary to discriminate between the different mechanisms of blockade and recovery. These results show that haditoxin had a higher potency for α7-nAChRs than for the other nAChRs. IC50 values for αβδϵ- and α3β2-nAChRs were in the same nanomolar range, whereas for α4β2-nAChRs, it was in the micromolar range.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of haditoxin on human nACHRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes. A, C, E, and G, inhibition of ACh-induced currents in αβδϵ- (neuromuscular junction) (A), α7- (C), α4β2- (E), and α3β2-nAChRs (G). Neuromuscular junction currents were activated by 10 μm ACh, whereas 200 μm was used to activate α7-, α4β2-, and α3β2-nAChRs. The first three traces are controls, followed by a 2-min exposure to several haditoxin concentrations ranging from 10 nm to 10 μm. Each experiment was terminated by a 8-min wash out. Little or no recovery was observed for αβδϵ- and α7-nAChRs, whereas partial to full recovery was observed for α4β2- and α3β2-nAChRs. Inhibition curves of the fitted data, IC50, and Hill coefficient (nH) for αβδϵ-nAChRs (B) were 0.55 μm and 0.7; for α7-nAChRs (D), they were 0.18 μm and 0.8; for α3β2-nAChRs (F), they were 0.5 μm and 1.1; and for α4β2-nAChRs (H), they were 2.6 μm and 0.7. Error bars indicate S.E.

Haditoxin Is a Dimer

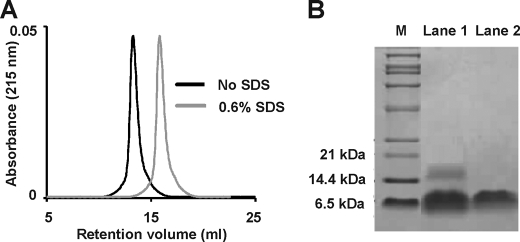

During the gel filtration of the crude venom, we observed that haditoxin eluted earlier when compared with other 3FTxs (Fig. 2A, most of the 3FTxs elutes in Peak 3). This led us to investigate the oligomeric states of this protein. Thus, we carried out analytical gel filtration experiments using a Superdex G-75 column. Protein, at concentrations (0.25–10 μm) covering the IC50 in CBCM (0.27 ± 0.07 μm) and RHD (1.85 ± 0.39 μm) preparations, was loaded onto the column. At all of these concentrations, the presence of a single peak corresponding to a relative molecular mass of 16.25 kDa was observed (Fig. 5A), supporting the existence of a dimeric species. To observe the effect of SDS on dimerization, we treated the protein (0.25–10 μm) with SDS and eluted using the same column. It eluted as a single peak with a Mr of 8.16 kDa (Fig. 5A), similar to the monomeric species.

FIGURE 5.

Dimerization of haditoxin. A, gel filtration profile of haditoxin with (gray) and without (black) SDS. 1 μm haditoxin was loaded onto a Superdex 75 column (1 × 30 cm) equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). The protein was eluted out with the 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) or 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.6% SDS at flow rate of 0.6 ml/min. B, Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE analysis of haditoxin with (lane 1) and without (lane 2) cross linker (BS3). M is the marker lane. The concentration of BS3 is 5 mm.

The dimerization was further confirmed by Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE analysis in the presence and absence of a cross-linker, BS3 (Fig. 5B). In the presence of BS3, both the dimeric and the monomeric species were visualized (Fig. 5B, lane 1), whereas only the monomeric species were observed in its absence (Fig. 5B, lane 2). These results, together with MS data (showing monomeric mass, Fig. 2C), indicate the existence of haditoxin as a homodimer in solution at pharmacologically relevant concentrations, and the dimerization occurs through non-covalent interactions. Further, as haditoxin loses its β-sheeted structure and becomes random coil in the presence of SDS (as indicated by CD studies; data not shown), its overall conformation may play a critical role in the dimerization.

Crystal Structure of Haditoxin

To determine the three-dimensional structure of haditoxin, we used the x-ray crystallographic method. Diffraction quality crystals of haditoxin were obtained with 0.1 m Tris, pH 8.5, 20% v/v ethanol (Hampton Research crystal screen 2, condition 44). Diffraction up to 1.55 Å was observed, and the crystals belonged to the space group P21 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection | |

| Cell parameters (Å) | a = 37.27, b = 41.29, c = 40.98, β = 106.4° |

| Space group | P21 |

| Molecules/asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50–1.55 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Observed reflections | 82,388 |

| Unique reflections | 17,366 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.1 (92.9) |

| Rsym (%)a | 0.093 |

| I/σ (I) | 40.2 (6.0) |

| Refinement and quality | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 20–1.55 |

| Rwork (%)b | 19.4 |

| Rfree (%)c | 22.5 |

| r.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| r.m.s.d. bond angles (deg) | 1.274 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | 15.1 |

| Number of protein atoms | 1408 |

| Number of waters | 114 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |

| Most favored regions | 88.9 |

| Additional allowed regions | 9.3 |

| Generously allowed regions | 1.9 |

| Disallowed regions | 0 |

a Rsym = Σ|Ii − 〈I〉|/Σ|I|, where Ii is the intensity of the ith measurement, and 〈I〉 is the mean intensity for that reflection.

b Rwork = Σ|Fobs − Fcalc|/Σ|Fobs|, where Fcalc and Fobs are the calculated and observed structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

c Rfree = as for Rwork, but for 10% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

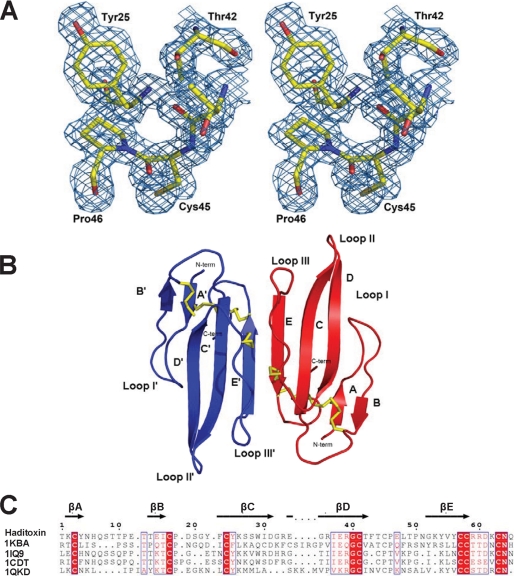

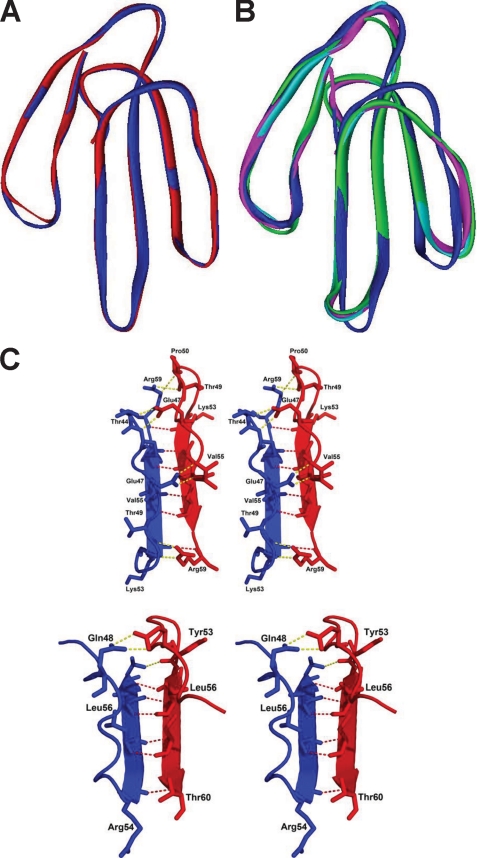

Structure Determination and Refinement

The structure of haditoxin was solved by the molecular replacement method (Molrep) (50). Initially, toxin-α, isolated from Naja nigricollis venom, was used as a search model (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1IQ9; sequence identity ∼48%). The rotation and translation resulted in a correlation factor of 0.07 and Rcryst of 0.57. Further minimization in Refmac (51) reduced the R factor to 0.42. An excellent quality electron density map was calculated at this stage, which allowed us to auto-build 90% of the haditoxin model with ARP/wARP (52). The resulting model with the electron density map was examined to manually build the rest of the model using the Coot program (53). After a few cycles of map fitting and refinement, we obtained an R factor of 0.194 (Rfree = 0.225) for reflections I > σI within 20-1.55 Å resolution. Throughout the refinement (Table 1), no noncrystallographic symmetry restraint was employed. All 65 residues (considering one subunit) are well defined in the electron density map (Fig. 6A), and statistics for the Ramachandran plot using PROCHECK (54) showed the presence of 88.9% of non-glycine residues in the most favored region. The coordinates and structure factors have been deposited with the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB) PDB (55) with the code 3HH7. The asymmetric unit consists of two monomers forming a tight dimer having an approximate dimension of 25 × 13 × 4 Å (Fig. 6B). This crystallographic dimer is consistent with the gel filtration and SDS-PAGE observations (Fig. 5). Both monomers are related by a two-fold symmetry, and their superposition yielded an r.m.s.d. of 0.2 Å for 65 Cα atoms (Fig. 7A). Each monomer adopts the common three-finger fold (11) consisting of three β-sheeted loops protruding from a central core, tightened by four highly conserved disulfide bridges (Cys-3–Cys-24, Cys-17–Cys-41, Cys-45–Cys-57, and Cys-58–Cys-63) (Fig. 6, B and C), and are structurally similar to short-chain α-neurotoxins such as toxin-α and erabutoxins (Fig. 7B). Loop I forms a two-stranded β-sheet (Lys-2–Tyr-4 and Thr-14–Ile-16), whereas loops II and III form a three-stranded β-sheet (Glu-34–Thr-42, Phe-23–Asp-31, and Lys-53–Cys-58). The antiparallel β-strands of the β-sheet are stabilized by main chain-main chain hydrogen bonding.

FIGURE 6.

Overall structure of haditoxin. A, stereo view of a portion of the final 2Fo − Fc map of haditoxin. The map was contoured at a level of 1.0 σ. B, monomers A and B are shown in blue and red, respectively. Disulfide bonds are shown in yellow. N and C termini (N-term and C-term), β-strands, and loops I, II, and III are labeled. C, structure-based alignment of three-finger toxins. Color coding of conserved residues is provided by boxed red text, and color coding of invariant residues is provided by red highlight. Accession numbers are shown on the left, and secondary structural elements of haditoxin are shown on top. Numbering is shown for haditoxin only. Sequence alignment was done by Strap (82) and displayed with ESPript (83).

FIGURE 7.

Structural details of haditoxin. A, superimposition of both subunits of haditoxin. Subunits A and B are shown in blue and red, respectively. B, superimposition subunit A of haditoxin with short-chain α-neurotoxins. Subunit A is shown in blue, erabutoxin-a is shown in magenta, erabutoxin-b is shown in cyan, and toxin-α is shown in green. C, stereo diagram of comparison of dimer interface of haditoxin (top) and κ-bungarotoxin (bottom). The residues to form the hydrogen bonds are labeled. The main chain-main chain hydrogen bonds are shown in red, and the other hydrogen bonds are shown in yellow.

Dimeric Interface

The dimeric interface was analyzed using the Protein Interfaces, Surfaces and Assemblies (PISA) server (56). It is mainly formed by loop III of each subunit. Strands D, C, E, E′, C′, and D′ form a six β-pleated sheet with an overall right-handed twist (Fig. 6B) in the dimer. Approximately 565 Å2 (or 12% of the total) surface areas and 17 residues of each monomer contribute to the dimerization. The close contacts between the monomers are maintained by 14 hydrogen bonds (<3.2 Å) and extensive hydrophobic interactions (Table 2). Six main chain-main chain hydrogen-bonding contacts exist across the interface involving strand E of monomer A and E′ of B (Table 2, Fig. 7C). Four are observed between the main chain amide hydrogen and carbonyl oxygen of Val-55 and Cys-57 from monomer A and Val-55′ and Cys-57′ from monomer B, and the remaining two exist between the carbonyl oxygen of Lys-53 (and Lys-53′) and the amide hydrogen of Arg-59 (and Arg-59′). In addition, there are another eight hydrogen-bonding contacts mediated through the side chains of Thr-44, Cys-45, Glu-47, Pro-50, and Arg-59 (Table 2, Fig. 7C). Two hydrophobic clusters further stabilize the dimeric structure. The side chains of Phe-23 and Leu-48 from both monomers form one cluster, whereas the disulfide bridge between Cys-45–Cys-57 and Val-55 of both monomers form the other. These observations strongly suggest the existence of haditoxin as non-covalent homodimeric species.

TABLE 2.

Hydrogen bonds in the dimeric interface of the haditoxin

| Hydrogen bonds | Monomer A | Monomer B | Distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Å | |||

| Main chain-main chain | Cys-57 (O) | Val-55 (N) | 2.93 |

| Val-55 (O) | Cys-57 (N) | 2.85 | |

| Cys-57 (N) | Val-55 (O) | 2.86 | |

| Val-55 (N) | Cys-57 (O) | 2.90 | |

| Lys-53 (O) | Arg-59 (N) | 3.10 | |

| Arg-59 (N) | Lys-53 (O) | 3.40 | |

| Side chain-side chain | Glu-47 (OE1) | Thr-44 (OG1) | 2.63 |

| Glu-47 (OE2) | Cys-45 (N) | 2.76 | |

| Pro-50 (O) | Arg-59 (NE) | 3.39 | |

| Thr-49 (O) | Arg-59 (NH2) | 3.37 | |

| Thr-44 (OG1) | Glu-47 (OE1) | 2.68 | |

| Cys-45 (N) | Glu-47 (OE2) | 2.81 | |

| Arg-59 (NH2) | Thr-49 (O) | 2.66 | |

| Arg-59 (NE) | Gly-52 (O) | 2.76 |

DISCUSSION

Nonenzymatic neurotoxins from snake venom belonging to the 3FTx family consist of closely related polypeptides with a molecular mass range of 6,500–8,000 Da. Functionally, most interfere with cholinergic neurotransmission and are highly specific for different subtypes of muscarinic or nicotinic cholinergic receptors (for details, see the Introduction). This underscores their immense potential as lead molecules in drug discovery and as research tools in the characterization of receptor subtypes.

Here, we have described the purification and characterization of a novel neurotoxin, haditoxin, from the venom of O. hannah. It is a non-covalent homodimer that produces potent postsynaptic neuromuscular blockade of the mammalian muscle (IC50 = 1.85 ± 0.39 μm) and avian muscle (IC50 = 0.27 ± 0.07 μm) (αβγδ) nAChRs (Fig. 3, A and C). In electrophysiological studies, it was an antagonist of muscle (αβδϵ) (IC50 = 0.55 μm) as well as neuronal α7- (IC50 = 0.18 μm), α3β2- (IC50 = 0.50 μm), and α4β2- (IC50 = 2.60 μm) nAChRs (Fig. 4). Interestingly, haditoxin exhibited a novel pharmacology with combined blocking activity on muscle (αβγδ) as well as neuronal (α7, α3β2, and α4β2) nAChRs but with the highest potency on α7-nAChRs, which is recognized by neither short-chain α-neurotoxins nor κ-neurotoxins.

The reversibility of this neuromuscular blockade was taxa-specific; it is partially reversible by washing in the chick neuromuscular junction, whereas it was almost irreversible in the rat neuromuscular junction. Earlier, we reported taxa-specific neurotoxicity of denmotoxin from Boiga dendrophila (12) and irditoxin from Boiga irregularis (13). Taxa specificity manifests the natural targeting of the venom toxins toward their prey (13, 57–59). Snakes from the Boiga sp. mainly feed on the non-mammalian prey such as birds (12, 13, 60), whereas elapids, including the king cobra, mainly prey on snakes and rodents and only occasionally and opportunistically on birds (61, 62). Venom compositions of snakes are known to be dependent on prey specificity to ensure efficiency in their capture and killing (58). Therefore, the taxa-specific reversibility of the neuromuscular blockade produced by haditoxin is likely due to the natural species specificity of the king cobra venom and not because of low toxicity.

Structurally Important Residues for Haditoxin

Haditoxin contains all 8 conserved cysteine residues that are essential for the three-finger folding (24, 63). They form four disulfide bridges located in the core region of the molecule. In addition, this molecule possesses several other structurally invariant residues, responsible for the stability of the three-finger fold. For example, Tyr-25 (numbering of the residues is according to erabutoxin-a, unless stated otherwise), the crucial residue stabilizing the antiparallel β-sheet structure (64), is conserved in a similar three-dimensional orientation. Similarly, the structurally invariant Gly-40, involved in the tight packing of the three-dimensional fold by accommodating the bulky side chain of the Tyr-25 (24), is also conserved. The 2 proline residues Pro-44 and Pro-48, potentially associated with the formation of the β-turn (24), are conserved in haditoxin as Pro-46 and Pro-50. The salt bridge between the N-terminal amino group and the carboxyl group of Glu-58 as well as the C-terminal carboxyl group and the guanidinium group of Arg-39 in erabutoxin-a (24) is maintained by the N-terminal amino group and the carboxyl group of Asp-58 as well as the C-terminal carboxyl group and the guanidinium group of the Arg-39 in haditoxin. Thus, the presence of these structurally invariant residues contributes to the stable three-finger fold of haditoxin.

Functionally Important Residues for Haditoxin

Extensive structure-function relationship studies on the short-chain α-neurotoxin, erabutoxin-a (24, 65, 66), and the long-chain α-neurotoxins, α-cobratoxin (67, 68) and α-bungarotoxin (69, 70), revealed the critical residues involved in the recognition of nAChRs by snake neurotoxins. The crucial residues for α-neurotoxins to bind to muscle (αβγδ) nAChRs are Lys-27, Trp-29, Asp-31, Phe-32, Arg-33, and Lys-47. Haditoxin possesses three of them (Trp-29, Asp-31, and Arg-33) in homologous positions. Additionally, each type of toxin possesses specific residues that recognize muscle or neuronal nAChRs. For muscle (αβγδ) nAChRs, these are His-6, Gln-7, Ser-8, Ser-9, and Gln-10 in loop I and Tyr-25, Gly-34, Ile-36, and Glu-38 in loop II of short-chain α-neurotoxins (65) and Arg-36 in loop II and Phe-65 in the C terminus tail of long-chain α-neurotoxins (67). His-6, Gln-7, and Ser-8 in the loop I and Tyr-25, Gly-34, Ile-37, and Glu-38 in the loop II are conserved in haditoxin as the muscle subtype-specific determinants of short-chain α-neurotoxins. Moreover, Arg-36, muscle subtype-specific determinant of long-chain α-neurotoxins, is also conserved in haditoxin. The presence of these multiple functional determinants may explain the potent neurotoxicity exhibited by haditoxin on mammalian and avian muscle (αβγδ) nAChR.

On the contrary, the specific determinants (Ala-28 and Lys-35; α-cobratoxin numbering) of long-chain α-neurotoxins toward the neuronal (α7) nAChRs (71) are not conserved in haditoxin. Significantly, haditoxin also lacks the fifth disulfide bridge responsible for the cyclization of loop II, which is considered to be a hallmark determinant for the ability of neurotoxins such as α-bungarotoxin and κ-bungarotoxins to interact with their specific neuronal nAChR targets (67, 71–74). This is somewhat surprising given the high affinity of haditoxin for α7- (IC50 = 0.18 μm), α3β2- (IC50 = 0.5 μm), and α4β2- (IC50 = 2.6 μm) nAChRs. Previously, candoxin, a non-conventional 3FTx (31), was found to be an exception of a 3FTx that did not have the fifth disulfide bridge in loop II (candoxin has a fifth disulfide bridge in loop I) but still retained the ability to interact with neuronal (α7) nAChRs (75). It was suggested thus that candoxin may likely interact with neuronal α7-nAChRs using alternate, novel points of contact. Likewise, it is plausible that haditoxin possesses unique combinations of determinants that enable its interaction with α7-, as well as α3β2- and α4β2-nAChRs. A detailed structure-function analysis to decipher these novel determinants is beyond the scope of this report.

In the case of κ-neurotoxins, which interact with neuronal α3β2- and α4β2-nAChRs with high affinity (26, 27), the critical functional residue was identified as Arg-34 (76). Haditoxin has Arg-33 in a homologous position, which may contribute in part to high affinity interaction with α3β2- (IC50 = 0.5 μm) and α4β2- (IC50 = 2.6 μm) nAChRs. Mutagenesis studies on κ-bungarotoxin revealed that the replacement of Pro-36 to an amino acid residue bearing a bulky, charged side chain, such as the Lys found in α-bungarotoxin, causes a 16-fold decrease in the efficacy of the toxin to block neurotransmission in the chick ciliary ganglion assay (76). Haditoxin bears an equivalent glycine residue, lacking a bulky, charged side chain, which can explain the high affinity of this toxin toward the neuronal (α3β2 and α4β2) nAChRs.

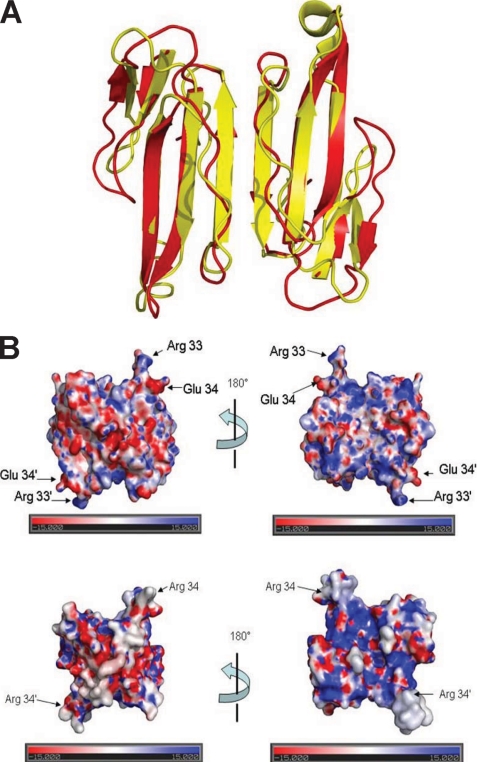

Comparison of Haditoxin with Other Dimeric 3FTxs

Few known examples of dimeric three-finger neurotoxins derived from snake venoms exist (13, 37, 72). Among them, the most well studied and characterized are the κ-neurotoxins, known to be composed of two identical monomers held together by non-covalent interactions (77, 78). The observed dimeric form of haditoxin, with the characteristic six β-pleated sheets, is similar to that formed by κ-bungarotoxin (77). Superposition of both molecules yielded an r.m.s.d. of 1.95 Å for 104 Cα atoms (Fig. 8A). The major deviations are located in the loops between the antiparallel β-strands. However, each monomer in κ-bungarotoxin is structurally homologous to long-chain α-neurotoxins unlike haditoxin, which resembles short-chain α-neurotoxins (Fig. 7C). The dimeric interface for both is maintained by six main chain-main chain hydrogen bonds (77). In addition, haditoxin has eight side chain hydrogen-bonding contacts between the monomers, whereas only three similar contacts were observed in κ-bungarotoxin (Fig. 7A) (77), suggesting that haditoxin forms tighter dimers than κ-bungarotoxin. The side chain interactions in κ-bungarotoxin are maintained by Phe-49, Leu-57, and Ile-20, which are strictly conserved in all κ-neurotoxins (77, 79). Mutagenesis studies have proven that replacing Phe-49 or Ile-20 with alanines renders a toxin with an apparent lack of ability to fold into the native structure, even as a monomer (79). The same result has been observed with deletion studies (deletion of Arg-54) with an aim to generate a 65-residue-long protein, as found in the α-neurotoxins, from the 66-residue-long κ-bungarotoxin (79), whereas haditoxin being a 65-residue-long protein lacks both Phe-49 and Ile-20 but still retains the intact dimeric structure. The electrostatic surface potentials for both molecules were apparently similar (Fig. 8B) except for the tip of loop II, which revealed a strong positive patch for haditoxin when compared with κ-bungarotoxin (77).

FIGURE 8.

Haditoxin versus κ-bungarotoxin. A, superimposition of haditoxin with κ-bungarotoxin. Haditoxin and κ-bungarotoxin are shown in red and yellow, respectively. B, electrostatic surface of haditoxin (top) and κ-bungarotoxin (bottom). The orientation is the same as in Fig. 6B. The locations of Arg-33 and Glu-34 of haditoxin and Arg-34 of κ-bungarotoxin are indicated.

Functionally, κ-neurotoxins interact with the neuronal (α3β2 and α4β2) nAChRs with high affinity (26, 27), whereas haditoxin interacts with both muscle (αβγδ) and a variety of neuronal (α7, α3β2, and α4β2) nAChRs. The crystal structure of the κ-bungarotoxin dimer showed that the guanidinium groups of the essential arginine residues, situated at the tip of the loop II, maintains nearly identical distance (44 Å) (77), like the acetylcholine binding sites in the pentameric receptor (30–50 Å) (80, 81). The κ-bungarotoxin dimer may both interact with the acetylcholine binding sites on a single neuronal receptor and physically block ion flow by spanning the channel (77, 79). However, this mode of interaction does not explain the inability of the κ-neurotoxins to block the muscle nAChRs. Haditoxin maintains a distance of ∼52 Å between the guanidinium groups of the critical arginine residues present in the turn region of the second loop, which is almost similar to the acetylcholine binding sites in the pentameric receptor mentioned above. However, unlike the κ-neurotoxins, haditoxin interacts with both muscle and neuronal nAChRs. This supports the fact that the dimeric toxins may have a unique mode of interaction with the nAChRs, which demands further investigation.

More recently, other heterodimeric 3FTxs from elapid venoms have been reported, including covalently (disulfide) linked homodimers of a long-chain α-neurotoxin (α-cobratoxin) and heterodimers of α-cobratoxin in combination with a variety of three-finger cytotoxins (72). Unlike haditoxin, all of these dimers are formed by covalent bonding (disulfide linkage) of the monomeric units. Functionally, the α-cobratoxin-cytotoxin heterodimers were able to block neuronal (α7) nAChRs, whereas the α-cobratoxin homodimer exhibited blockade of both neuronal α7- and α3β2-nAChRs, unlike monomeric α-cobratoxin, which interacts with muscle (αβγδ) and neuronal (α7) nAChRs (72).

Our laboratory has also reported on a colubrid venom-derived covalently linked heterodimeric 3FTx, irditoxin (13), which was found to target muscle (αβγδ) nAChRs, in sharp contrast to the reported function of elapid dimeric toxins (72). Another distinguishing feature was that the subunits of irditoxin structurally resemble non-conventional 3FTxs (13). Haditoxin is both structurally and functionally distinct from the α-cobratoxin hetero/homodimers as well as irditoxin. Structurally, haditoxin is a non-covalently linked homodimer of the short-chain α-neurotoxin type, and functionally, it has a broad pharmacological profile with high affinity and selectivity for muscle (αβγδ) and neuronal (α7, α4β2, and α3β2) nAChRs. Haditoxin exhibits a unique structural and functional profile and is the first reported dimeric 3FTx interacting with the muscle (αβγδ) nAChR as well as the first short-chain type of α-neurotoxin to interact with neuronal α7-nAChR with nanomolar affinity.

This work was supported by research grant from the Biomedical Research Council (BMRC), Agency for Science and Technology, Singapore (BMRC Grant R154-000-172-316) (to R. M. K.) and by Academic Research Fund funding support (Grant R154000438112) from National University of Singapore, Singapore (to J. S.).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3HH7) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1.

- nAChR

- nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

- mAChR

- muscarinic acetylcholine receptors

- 3FTx

- three-finger toxin

- MT

- muscarinic toxin

- BS3

- bis(sulfosuccinimidyl) suberate

- CBCM

- chick biventer cervicis muscle

- RHD

- rat hemidiaphragm muscle

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- RP-HPLC

- reverse phase-high performance liquid chromatography

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- ESI-MS

- electrospray mass ionization-MS

- Tricine

- N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine

- MTLP

- muscarinic toxin-like protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey A. L. (1991) Snake Toxins, pp. 1–90, Pergamon Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewis R. J., Garcia M. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 790–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey A. L. (2002) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langley J. N. (1907) J. Physiol. 36, 347–384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz B., Thesleff S. (1957) J. Physiol. 138, 63–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grutter T., Changeux J. P. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 459–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Changeux J. P. (1990) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 11, 485–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor P., Molles B., Malany S., Osaka H. (2002) in Perspectives in Molecular Toxinology (Ménez A. ed) pp. 271–280, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, England [Google Scholar]

- 9.Changeux J. P., Kasai M., Lee C. Y. (1970) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 67, 1241–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun L. M., Patrick J. W. (1997) Adv. Pharmacol. 39, 191–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kini R. M. (2002) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29, 815–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawlak J., Mackessy S. P., Fry B. G., Bhatia M., Mourier G., Fruchart-Gaillard C., Servent D., Ménez R., Stura E., Ménez A., Kini R. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29030–29041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawlak J., Mackessy S. P., Sixberry N. M., Stura E. A., Le Du M. H., Ménez R., Foo C. S., Ménez A., Nirthanan S., Kini R. M. (2009) FASEB J. 23, 534–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pahari S., Mackessy S. P., Kini R. M. (2007) BMC. Mol. Biol. 8, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang M., Häggblad J., Heilbronn E. (1987) Toxicon 25, 1019–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsetlin V. (1999) Eur. J. Biochem. 264, 281–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar T. K., Jayaraman G., Lee C. S., Arunkumar A. I., Sivaraman T., Samuel D., Yu C. (1997) J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 15, 431–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Weille J. R., Schweitz H., Maes P., Tartar A., Lazdunski M. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 2437–2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDowell R. S., Dennis M. S., Louie A., Shuster M., Mulkerrin M. G., Lazarus R. A. (1992) Biochemistry 31, 4766–4772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajagopalan N., Pung Y. F., Zhu Y. Z., Wong P. T., Kumar P. P., Kini R. M. (2007) FASEB J. 21, 3685–3695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricciardi A., le Du M. H., Khayati M., Dajas F., Boulain J. C., Menez A., Ducancel F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18302–18310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohno M., Ménez R., Ogawa T., Danse J. M., Shimohigashi Y., Fromen C., Ducancel F., Zinn-Justin S., Le Du M. H., Boulain J. C., Tamiya T., Ménez A. (1998) Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 59, 307–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nirthanan S., Gwee M. C. (2004) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 94, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endo T., Tamiya N. (1991) in Snake Toxins (Harvey A. L. ed) pp. 165–222, Pergamon Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 25.Servent D., Antil-Delbeke S., Gaillard C., Corringer P. J., Changeux J. P., Ménez A. (2000) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 393, 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant G. A., Chiappinelli V. A. (1985) Biochemistry 24, 1532–1537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf K. M., Ciarleglio A., Chiappinelli V. A. (1988) Brain Res. 439, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Servent D., Fruchart-Gaillard C. (2009) J. Neurochem. 109, 1193–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey A. L., Kornisiuk E., Bradley K. N., Cerveñansky C., Durán R., Adrover M., Sánchez G., Jerusalinsky D. (2002) Neurochem. Res. 27, 1543–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olianas M. C., Ingianni A., Maullu C., Adem A., Karlsson E., Onali P. (1999) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 288, 164–170 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nirthanan S., Charpantier E., Gopalakrishnakone P., Gwee M. C., Khoo H. E., Cheah L. S., Bertrand D., Kini R. M. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17811–17820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lumsden N. G., Fry B. G., Ventura S., Kini R. M., Hodgson W. C. (2005) Toxicon 45, 329–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starkov V. G., Poliak Iu. L., Vul'fius E. A., Kriukova E. V., Tsetlin V. I., Utkin Iu. N. (2009) Bioorg. Khim. 35, 15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuruppu S., Reeve S., Smith A. I., Hodgson W. C. (2005) Biochem. Pharmacol. 70, 794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan L. C., Kuruppu S., Smith A. I., Reeve S., Hodgson W. C. (2006) Neuropharmacology 51, 782–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aird S. D., Womble G. C., Yates J. R., 3rd, Griffin P. R. (1999) Toxicon 37, 609–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiappinelli V. A., Lee J. C. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 6182–6186 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chiappinelli V. A., Wolf K. M. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 8543–8547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginsborg B. L., Warriner J. (1960) Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 15, 410–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bülbring E. (1997) Br. J. Pharmacol. 120, 3–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hogg R. C., Bandelier F., Benoit A., Dosch R., Bertrand D. (2008) J. Neurosci. Methods 169, 65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staros J. V. (1982) Biochemistry 21, 3950–3955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pung Y. F., Wong P. T., Kumar P. P., Hodgson W. C., Kini R. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 13137–13147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coulson F. R., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2004) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 308, 760–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weiser M., Mutschler E., Lambrecht G. (1997) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 356, 671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warrell D. A., Looareesuwan S., White N. J., Theakston R. D., Warrell M. J., Kosakarn W., Reid H. A. (1983) Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 286, 678–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laothong C., Sitprija V. (2001) Toxicon 39, 1353–1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palma E., Bertrand S., Binzoni T., Bertrand D. (1996) J. Physiol. 491, 151–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (1997) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 30, 1022–1025 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vagin A. A., Steiner R. A., Lebedev A. A., Potterton L., McNicholas S., Long F., Murshudov G. N. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2184–2195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perrakis A., Morris R., Lamzin V. S. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 458–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Berman H. M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T. N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I. N., Bourne P. E. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krissinel E., Henrick K. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barlow A., Pook C. E., Harrison R. A., Wüster W. (2009) Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 2443–2449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daltry J. C., Wüster W., Thorpe R. S. (1996) Nature 379, 537–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pahari S., Bickford D., Fry B. G., Kini R. M. (2007) BMC. Evol. Biol. 7, 175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mackessy S. P., Sixberry N. M., Heyborne W. H., Fritts T. (2006) Toxicon 47, 537–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mehrtens J. (1987) Living Snakes of the World, pp. 245–281, Sterling, New York [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coborn J. (1991) The Atlas of Snakes of the World, pp. 452–453, TFH Publications, New Jersey [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ménez A., Bouet F., Guschlbauer W., Fromageot P. (1980) Biochemistry 19, 4166–4172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Torres A. M., Kini R. M., Selvanayagam N., Kuchel P. W. (2001) Biochem. J. 360, 539–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Teixeira-Clerc F., Ménez A., Kessler P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25741–25747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trémeau O., Lemaire C., Drevet P., Pinkasfeld S., Ducancel F., Boulain J. C., Ménez A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 9362–9369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bourne Y., Talley T. T., Hansen S. B., Taylor P., Marchot P. (2005) EMBO J. 24, 1512–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antil S., Servent D., Ménez A. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 34851–34858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fruchart-Gaillard C., Gilquin B., Antil-Delbeke S., Le Novère N., Tamiya T., Corringer P. J., Changeux J. P., Ménez A., Servent D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3216–3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dellisanti C. D., Yao Y., Stroud J. C., Wang Z. Z., Chen L. (2007) Nat. Neurosci. 10, 953–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Antil-Delbeke S., Gaillard C., Tamiya T., Corringer P. J., Changeux J. P., Servent D., Ménez A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29594–29601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Osipov A. V., Kasheverov I. E., Makarova Y. V., Starkov V. G., Vorontsova O. V., Ziganshin R. Kh., Andreeva T. V., Serebryakova M. V., Benoit A., Hogg R. C., Bertrand D., Tsetlin V. I., Utkin Y. N. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 14571–14580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grant G. A., Luetje C. W., Summers R., Xu X. L. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 12166–12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Servent D., Mourier G., Antil S., Ménez A. (1998) Toxicol. Lett. 102–103, 199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nirthanan S., Charpantier E., Gopalakrishnakone P., Gwee M. C., Khoo H. E., Cheah L. S., Kini R. M., Bertrand D. (2003) Br. J. Pharmacol. 139, 832–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fiordalisi J. J., al-Rabiee R., Chiappinelli V. A., Grant G. A. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 3872–3877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dewan J. C., Grant G. A., Sacchettini J. C. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 13147–13154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oswald R. E., Sutcliffe M. J., Bamberger M., Loring R. H., Braswell E., Dobson C. M. (1991) Biochemistry 30, 4901–4909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grant G. A., Al-Rabiee R., Xu X. L., Zhang Y. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 3353–3358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herz J. M., Johnson D. A., Taylor P. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 12439–12448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Unwin N. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 229, 1101–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gille C., Frömmel C. (2001) Bioinformatics 17, 377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gouet P., Courcelle E., Stuart D. I., Métoz F. (1999) Bioinformatics 15, 305–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]