Abstract

Serum amyloid A (SAA) is a major acute phase protein involved in multiple physiological and pathological processes. This study provides experimental evidence that CD36, a phagocyte class B scavenger receptor, functions as a novel SAA receptor mediating SAA proinflammatory activity. The uptake of Alexa Fluor® 488 SAA as well as of other well established CD36 ligands was increased 5–10-fold in HeLa cells stably transfected with CD36 when compared with mock-transfected cells. Unlike other apolipoproteins that bind to CD36, only SAA induced a 10–50-fold increase of interleukin-8 secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells when compared with control cells. SAA-mediated effects were thermolabile, inhibitable by anti-SAA antibody, and also neutralized by association with high density lipoprotein but not by association with bovine serum albumin. SAA-induced cell activation was inhibited by a CD36 peptide based on the CD36 hexarelin-binding site but not by a peptide based on the thrombospondin-1-binding site. A pronounced reduction (up to 60–75%) of SAA-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion was observed in cd36−/− rat macrophages and Kupffer cells when compared with wild type rat cells. The results of the MAPK phosphorylation assay as well as of the studies with NF-κB and MAPK inhibitors revealed that two MAPKs, JNK and to a lesser extent ERK1/2, primarily contribute to elevated cytokine production in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. In macrophages, four signaling pathways involving NF-κB and three MAPKs all appeared to contribute to SAA-induced cytokine release. These observations indicate that CD36 is a receptor mediating SAA binding and SAA-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion predominantly through JNK- and ERK1/2-mediated signaling.

Keywords: Cell/Epithelial, Cytokines, Lipoprotein/LDL, Lipoprotein/Receptor, Peptides, Signal Transduction/Protein Kinases/MAP, CD36 receptor, scavenger receptors class B, serum amyloid A

Introduction

During infection, acute inflammation, trauma, neoplastic growth, or any other tissue damage in general, the host undergoes a series of biochemical and physiological changes known as the acute phase response (APR),3 a reaction that plays a critical role in the innate immune response to tissue injury (1). APR features a cascade of events leading to the hepatic production of acute phase proteins that play an important role in the defense response of the host. Serum amyloid A (SAA), normally present in plasma in only trace amounts, is a major acute phase reactant, whose plasma levels may increase up to 1000-fold (1–3) within hours in response to various insults. SAA is an amphipathic α-helical apolipoprotein that is transported in the circulation primarily in association with high density lipoprotein (HDL) (4–6). Although acute phase SAA is predominantly expressed and produced by liver cells, there are growing numbers of reports describing its extrahepatic production by various tissues and cells. In humans, the expression and production of acute phase SAA have been found in several cell types within atherosclerotic lesions, including endothelial cells, macrophages, adipocytes, and smooth muscle cells (7) as well as in the epithelial cells of several normal tissues (8).

In addition to its well established acute response to inflammatory stimuli, an SAA response can also be observed in some chronic inflammatory conditions. Thus, SAA was found to be expressed in the brains of patients with Alzheimer disease (9) and in synovial fibroblasts of rheumatoid arthritis patients (10). Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated a significant association of altered SAA levels with several pathological states, particularly chronic inflammatory diseases such as secondary amyloidosis (11, 12), atherosclerosis (13, 14), and rheumatoid arthritis (15, 16). In addition, SAA levels are increased in conditions associated with increased cardiovascular risk, including obesity (17, 18), insulin resistance (17, 19), metabolic syndrome (20), and diabetes (17, 19, 21).

In vitro studies have suggested a number of pathways involving SAA in host defense mechanisms, inflammation, and atherogenesis. Lipid-poor SAA can act as a chemoattractant for inflammatory cells such as monocytes, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and T-lymphocytes (22, 23), all of which are involved in host defense mechanisms. It has been reported that SAA significantly stimulates the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by cultured human neutrophils, lymphocytes (24), and THP-1 monocytic cells (5). SAA can act as opsonin for Gram-negative bacteria, thereby enhancing bacterial phagocytosis as well as bacterium-stimulated cytokine release by peripheral blood mononuclear cell-derived macrophages (25). By displacing apoA-I from HDL (26), lipoprotein-associated SAA may play a role in redirecting HDL to the sites of tissue destruction and cholesterol accumulation (27). In addition, non-HDL-associated SAA promotes cholesterol efflux by both ABCA1-dependent and -independent mechanisms (28). SAA may also contribute to HDL-mediated clearance of cellular cholesterol by modulating lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase activity (29) as well as by modulating cholesterol metabolism by serving as a cholesterol-binding protein (30).

The importance of SAA in various physiological and pathological processes has raised considerable interest in the identification of receptors that could potentially mediate binding/internalization and pro-inflammatory effects of SAA. Recent studies revealed several proteins that are capable of binding and/or mediating various SAA activities. FPRL1 (formyl peptide receptor like-1), a protein found in neutrophils, has been shown to mediate SAA-induced leukocyte chemotaxis (31) as well as release of cytokines and matrix metalloproteinase-9 from human leukocytes (32). The scavenger receptor SR-BI has been demonstrated to mediate the cholesterol efflux function of HDL-associated SAA (33), whereas its human orthologue CLA-1 has been shown to internalize and mediate the pro-inflammatory activity of lipid-poor SAA via MAPK signaling pathways (34). Finally, recent experimental evidence suggests that toll-like receptors (TLRs) act as novel SAA receptors. TLR2 has been demonstrated to bind SAA and mediate SAA-stimulated pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in bone marrow-derived macrophages (35), while functional TLR4 was shown to be required for SAA-induced NO production through the activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs in murine peritoneal macrophages (36).

Both TLRs and scavenger receptors are abundantly expressed in mononuclear phagocyte lineage cell types and play an essential role in innate immunity as pattern recognition receptors capable of recognizing a broad range of molecular patterns commonly found on pathogens. A widely accepted concept is that ligand binding to scavenger receptors leads to endocytosis and lysosomal degradation (37, 38), whereas engagement of TLRs transmits transmembrane signals to activate NF-κB and MAPK pathways (39–41). Microbial recognition, signaling, and modulation of TLR responses are known to require the presence of co-receptors/accessory molecules. By analogy with CD14 that is required for ligand recruitment to TLR4, recent findings demonstrated that scavenger receptor CD36 is an essential co-receptor involved in recognizing and presenting lipoteichoic acid and certain diacylglycerides to TLR2/6-mediated signaling pathways (42, 43). At the same time, there is mounting evidence supporting an essential role of scavenger receptors as independent signaling molecules capable of activating signaling pathways upon ligand binding (44–46). In our previous study (34), we demonstrated that human class B scavenger receptor CLA-1 could function as an SAA signaling receptor, mediating its cytokine-like activity via a MAPK signaling pathway.

CD36 is an 88-kDa double-spanning plasma membrane glycoprotein and a member of the class B scavenger receptor family. As a pattern recognition receptor, CD36, by analogy with CLA-1/SR-BI, binds a broad variety of ligands, including native, oxidized, and acetylated low density lipoprotein (LDL) (47, 48), anionic phospholipids (49), long chain fatty acids, thrombospondin-1 (50), fibrillar β-amyloid, (51), and apoptotic cells (52). Most recent studies implicated class B scavenger receptors, SR-BI and CD36, in recognizing ligands that trigger an innate immune response. In particular, these ligands include Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (53–55), as well as the structural components of their bacterial cell walls (42, 54, 55). Synthetic amphipathic peptides, possessing one or more class A amphipathic helices in their structure, have been earlier shown to be potent ligands for both CLA-1/SR-B1 and CD36 receptors (34, 55, 56). The discovery of the multiple ligands shared by these two scavenger receptors along with the fact that SAA is also known to be an amphipathic protein with two amphipathic α-helical regions in the 1–18 N-terminal and 72–86 C-terminal sequences (3) prompted us to investigate the potential role of CD36 as an SAA receptor for both uptake and signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

All media, serum preparations, cell trackers, reactive fluorescent dyes and antibiotics were obtained from Invitrogen. Recombinant synthetic human apo-SAA was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). The lipid content of the recombinant apo-SAA was analyzed by the phospholipids B enzymatic method (Wako, Richmond, VA), and the cholesterol content was determined by an enzymatic cholesterol method on a Cobas Fara II analyzer (Roche Applied Science). These assays indicated that the SAA preparation contained only small amounts of phospholipids (5 ng/μg) and cholesterol (<2 ng/μg) and hence was considered as a lipid-poor form of SAA throughout this study. The endotoxin level in both SAA and HDL preparations was less than 0.1 ng per μg (1 EU/μg). The anti-CD36 monoclonal antibody FA16 was purchased from Abcam Inc. (Cambridge, MA). Anti-SAA polyclonal IgG was purified by affinity chromatography from a rabbit anti-recombinant human SAA serum obtained through Custom Polyclonal Antibody Service (Primm Biotech, Needham, MA). Synthetic amphipathic peptides were synthesized by a solid phase procedure (57, 58). Peptide sequences were described in a previous report (59). CD36-derived peptides were synthesized by the CBER/FDA Core Facility (Bethesda). Human HDL and LDL, as well as apolipoproteins A-I (apoA-I) and A-II (apoA-II), were purchased from EMD Biosciences (San Diego). Extensively oxidized LDL (oxLDL) was prepared by incubation with 5 μm CuSO4 at 37 °C for 24 h as described previously (60). The MAPK inhibitors PD98059, SB203580, SP600125 were purchased from EMD Biosciences. The NF-κB inhibitors, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC) and sulfasalasine, recombinant mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, LPS from Salmonella enterica (serotype Minnesota), and Staphylococcus aureus LTA were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Cultures

HeLa (Tet-Off) cells were transfected with FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics) using the expression plasmid pTRE2 (Clontech), encoding a human CD36 protein (pTRE2-CD36). Cells were co-transfected with pTRE2-hCD36 and pTK-Pur (Clontech), using a 1:20 ratio, and selected with 400 μg/ml puromycin. Puromycin-resistant cells were screened for the expression of the human CD36 protein utilizing mouse anti-hCD36 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) in Western blotting. The HEK293 cell line was stably transfected with CD36 pIRES-hrGFP-2a plasmid (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) followed by selecting cells with the highest green fluorescent protein expression. HeLa (Tet-Off) cells (Clontech), hCD36-overexpressing HeLa cells, as well as the human embryonic kidney cell line HEK293 (ATCC, Manassas, VA), both wild type and CD36-overexpressing, were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mm glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 μg/ml G418 at 37 °C in a 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere. THP-1 cells, a human monocyte cell line (ATCC), were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with the same additives as indicated above. Rat cd36-null (cd36−/−) and wild type (cd36+/+) macrophages were isolated from bone marrow cells of spontaneously hypertensive Wistar-Kioto male rats (SHR/NCrl) and its control strain Wistar-Kyoto/NCrl (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA), respectively. Initial breeding pairs of cd36−/− mice were generously provided by Dr. K. Moore (Harvard Medical School, Lipid Metabolism Unit). Mice used in these studies were propagated by homozygous mating colonies and maintained at the National Institutes of Health pathogen-free animal facility. Murine cd36−/− and cd36+/+ macrophages were isolated from bone marrow cells of CD36 null and control wild type mice, respectively. The macrophages were differentiated by culturing in RPMI 1640 medium, 20% FCS, in the presence of 10 ng/ml mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor and 10 ng/ml mouse IL-4 for 7–10 days. Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells were generated from primary cultures of femoral marrow by culturing in the presence of 10 ng/ml mouse recombinant granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for 7–10 days. Kupffer cells (KC) were isolated from livers of CD36-deficient and normal rats using the method described by Smedsrød et al. (61), with some modifications (62), using OptiPrep Density gradient reagent (Sigma) instead of Percoll for density gradient centrifugation. In brief, the liver was perfused with 500 ml of Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution followed by the perfusion with 50 ml of 0.05% collagenase type H (Invitrogen) in Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 5 μm CaCl2. Hepatocytes were sedimented by repetitive centrifugations for 3 min at 50 × g in ice-cold Hanks' balanced salt solution. Supernatants containing sinusoidal nonparenchymal liver cells were collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g. Pelleted sinusoidal nonparenchymal liver cells were resuspended in 18% of OptiPrep density gradient reagent in Hanks' balanced salt solution and centrifuged at 1500 × g for 20 min. The sinusoidal nonparenchymal liver cells, banded at the top of the supernatant, were collected and pelleted by additional centrifugation for 5 min at 300 × g. The sinusoidal nonparenchymal liver cells suspension was plated in serum-free DMEM into 96-well culture plates for 15 min to allow KC to attach and spread. Nonattached cells were removed from the culture plates by extensive washing, and the KC were further cultivated in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS and 10 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

Fluor-labeled Ligand Uptake

SAA, native and oxidized lipoproteins, apoA-I, apoA-II, L3D-37pA, and BSA were conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488, using a protein labeling kit (Invitrogen) following the vendor's instructions. HeLa cells were incubated with fluoro-labeled ligands at 37 °C for 1 h and then washed extensively with phosphate-buffered saline, detached with Cellstripper dissociation solution (Mediatech, Herndon, VA), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and analyzed by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS, model A; Hitachi).

Competition Studies with Alexa Fluor 488 SAA

CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells grown in 24-well plates were incubated with 5 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 488 SAA without or with increasing concentrations of unlabeled ligands at 37 °C for 2 h, then washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline, and detached from the plate surface by incubation in 200 μl of Cellstripper solution for 30 min at room temperature with continuous rocking on Rocker II (Boekel Scientific). Aliquots of cell suspension were transferred into 96-well black microplates and were read in a fluorescence plate reader (Wallac Victor 1420 Multilabel Counter, PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

125I-SAA Binding Assay

The recombinant human SAA preparation was iodinated by the Iodogen method (Pierce) to a specific activity of 200–300 cpm/ng protein. Confluent HeLa cells, mock-transfected and CD36-overexpressing, grown on 24-well plates were incubated in serum-free DMEM for 24 h prior to the onset of the assay. Saturation binding experiments were performed at 4 °C using 125I-SAA concentrations between 1 and 10 μg/ml. All incubations were performed in DMEM containing 20 mg/ml BSA and 20 mm HEPES. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 20-fold excess unlabeled SAA. After a 2-h incubation on ice, the cells were rinsed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and detached with Cellstripper dissociation solution (Mediatech, Herndon, VA). Aliquots of the resulting cell suspension were utilized for radioactivity measurements as reported earlier (63). Specific binding was determined as the difference between total and nonspecific binding and normalized by the protein content.

Cytokine Secretion Analyses

Cytokine secretion was analyzed in culture supernatants after a 20-h period of incubation in serum-free media with or without BSA (2 mg/ml) utilizing commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for human IL-8 (Invitrogen), rat IL-6, and rat TNF-α (Pierce) following the manufacturer's instructions. All samples and standards were measured in duplicate.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription-PCR

Cells were seeded into 6-well culture plates, and the total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommended protocol. RNA samples were reverse-transcribed by Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Superscript Reverse Transcription; Invitrogen) and oligo(dT)15 primers (Promega, Madison, WI). 5′-Fluorescein-labeled primers were obtained from Operon Biotechnologies (Huntsville, AL). cDNA was amplified in a System 2400 DNA thermal cycler (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) with denaturation for 1 min at 94 °C, annealing for 1 min at temperatures specified below for each pair of primers, and extension for 2 min at 72 °C. Primer sequences and specific PCR conditions are summarized in Table 1. PCR products were separated by PAGE using 8% TBE gels (Invitrogen), and the intensity of the fluorescent signal for each band was detected using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primer sequences used for reverse transcription-PCR

| Gene | Oligonucleotides sequences 5′ to 3′ | Annealing temperature | Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| °C | |||

| GAPDH | GTCTTCACCACCATGGAGAAG | 50 | 28 |

| GCTTCACCACCTTCTTGATGTCATC | |||

| CD36 | GCGACATGATTAATGGTACAGATGC | 55 | 30 |

| GATGGCTTGACCAATAGGTTGAC | |||

| SR-B1 | CCACCCAACGAAGGCTTCTGC | 50 | 28 |

| CTGAATGGCCTCCTTATCC | |||

| TLR2a | AAGCTTTCCAAGGAAGAATCCTCCAATCAGGCTTCTC | 61 | 44 |

| TCTAGATGGGAACCTAGGACTTTATCGCAGCTCTCAG | |||

| TLR4a | GGTACCACGCATTCACAGGGCCACTGCTGCTCAC | 63 | 36 |

| GCTGCCTAAATGCCTCAGGGGATTAAAGCTCAG | |||

| FPRL1b | ACGGTGAGGAGTATTCTGACGG | 58 | 45 |

| GACGCTGGTGTACATGTTGTGG |

Preparation and Analysis of SAA·HDL Complexes

HDL (2 mg/ml) was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with increasing concentrations (from 10 μg/ml to 1 mg/ml) of Alexa Fluor 488 SAA (for native electrophoresis analysis) or unlabeled SAA (for cytokine secretion assays), thus imitating different SAA/HDL molar ratios found under physiological conditions or during APR. Following the incubation, aliquots of the incubation mixture were analyzed on 4–20% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) under nondenaturing conditions, and Alexa Fluor 488 signal was detected using a Typhoon 9200 imager (Amersham Biosciences).

Pepscan Analysis

132 overlapping (by 3 amino acids) 20-mer peptides, spanning amino acids 28–440 of the CD36 extracellular domain, were spot-synthesized on a Whatman 50 cellulose membrane (JPT Peptide Technologies GMBH, Berlin, Germany) and ligand-blotted using Alexa Fluor 488 SAA. Briefly, after membrane blocking in DMEM containing 2 mg/ml BSA at 37 °C for 2 h with continuous rocking, it was subjected to a 2-h incubation with 5 μg/ml of Alexa Fluor 488 SAA in the same media followed by the triple washing, 5-min each, in phosphate-buffered saline containing 10% FCS at room temperature. Fluorescent spots of the membrane were visualized using a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (GE Healthcare).

Measurement of Lactate Dehydrogenase

Levels of the lactate dehydrogenase as an indicator of the cell membrane damage and cytotoxicity were analyzed in cell culture supernatants using the Synchron LX-20 automated chemistry analyzer (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA).

Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Assay

The endotoxin activity of recombinant human SAA was determined by an automated Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Kinetic-QCL, BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. This assay has an analytical sensitivity of 0.005 EU/ml (∼0.5 pg of highly purified LPS/ml).

Statistical Analyses

All data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. Differences between groups were analyzed by the Student's t test, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

SAA Receptor Expression in HEK293 Cell Lines

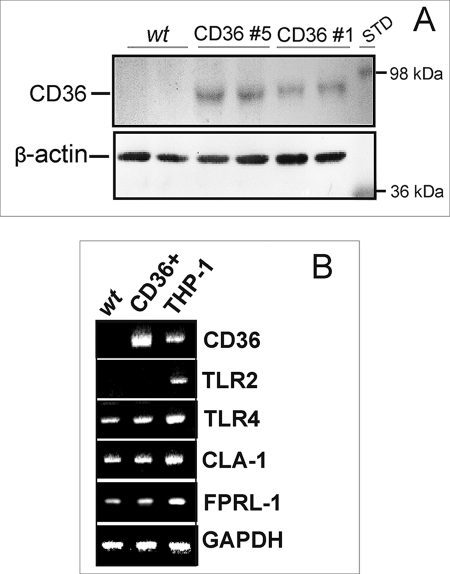

The results of the Western blot analyses did not reveal any detectable expression of CD36 protein in wild type HEK293 cells. Two CD36-transfected clones demonstrating different levels of CD36 protein expression (Fig. 1A) were used in our study. Using reverse transcription-PCR analyses, we performed a comparative expression assessment of other known SAA receptors in WT HEK293 cells versus CD36-overexpressing clone 5. As shown in Fig. 1B, WT and CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells demonstrated similar levels of mRNA expression for CLA-1, TLR4, and FPRL-1, which are known to be capable of mediating SAA binding and signaling (32, 34, 36). Although it was previously reported that the HEK293 cell line has little or no expression of TLR2 and TLR4 (66, 67), we observed readily detectable levels of TLR4 mRNA expression in both CD36-overexpressing and control cells but no TLR2 expression in either WT or CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cell lines.

FIGURE 1.

Expression levels of CD36 and other known receptors of SAA in wild type (wt) and CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. A, CD36 protein expression as determined by Western blot analyses in WT and two clones of CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. STD, standard. B, comparison of mRNA expression levels assessed by reverse transcription-PCR analysis for different SAA receptors in WT, CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells, and the THP-1 cell line. Each sample was analyzed for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH) mRNA as a housekeeping gene. The data are from one of three independent determinations that yielded similar results.

Uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled SAA Is Enhanced in hCD36-transfected Versus Mock-transfected HeLa Cells

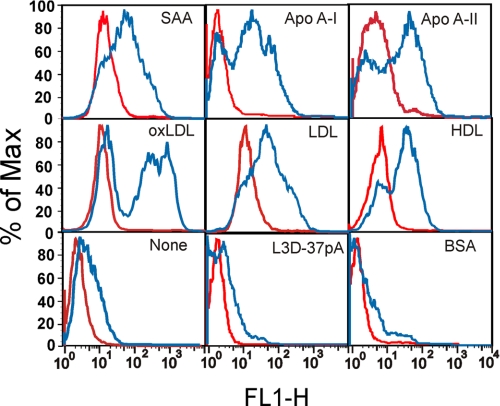

Consistent with the well established role of CD36 as a receptor for native lipoproteins (68) as well as for modified LDL (48), our FACS analyses demonstrated that the uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled HDL (∼4-fold increase), LDL (∼6-fold increase), and oxLDL (∼5-fold increase) was increased in CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells when compared with mock-transfected cells (Fig. 2). CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells demonstrated an ∼7-fold increase in Alexa Fluor 488-labeled SAA uptake when compared with control cells (Fig. 2). As could be predicted from the presence of α-helical motifs in apoA-I and apoA-II, both apolipoproteins also appeared to be CD36 agonists, as CD36-overexpressing cells also demonstrated an ∼10-fold increase in uptake for these apolipoproteins when compared with mock-transfected cells. In contrast, no appreciable uptake of L3D-37pA or BSA, both lacking an α-helical motif, was observed.

FIGURE 2.

Uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled ligands in CD36-overexpressing and mock-transfected HeLa cells. Cells were incubated with each of the following ligands for 1 h at 37 °C: 2.5 μg/ml SAA, 5 μg/ml oxLDL, LDL, or HDL, 10 μg/ml apoA-I, apoA-II, BSA or L-3D37pA. The uptake of each ligand in CD36-overexpressing (blue line) or mock-transfected (red line) cells is indicated on the plot area. Cell-associated fluorescence was estimated by FACS analyses. Data are from one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results.

Competition of Known CD36 Ligands with Alexa Fluor 488 SAA Uptake in CD36-overexpressing HeLa Cells

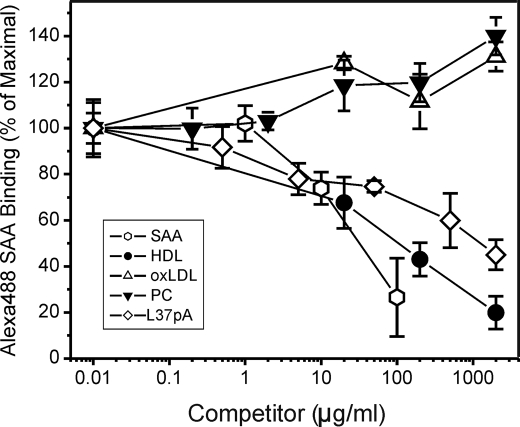

The potency of known CD36 ligands, including lipoproteins and synthetic peptides, as inhibitors of Alexa Fluor 488 SAA uptake was analyzed using CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells. Data in Fig. 3 show that unlabeled SAA competed with Alexa Fluor 488 SAA in a dose-dependent manner. HDL also efficiently competed with labeled SAA, and in contrast, neither preparation of phosphatidylcholine micelles nor oxLDL had any inhibitory effect upon Alexa Fluor 488 SAA uptake in CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells. Because SAA is typically associated with lipoproteins or bound to apolipoprotein-free phospholipids in vivo, micellar complexes of phosphatidylcholine with an apoA-I mimetic peptide L-37pA (formed in molar ratio 1:2.5) were analyzed. L-37pA blocked SAA uptake by as much as 55%. No competition was found with the L3D-37pA peptide that did not interact with CD36 (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 3.

Competition of CD36 ligands with Alexa Fluor 488 SAA uptake in CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells. Cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml Alexa Fluor 488 SAA without or with indicated concentrations of unlabeled competitors for 2 h at 37 °C. Unlabeled SAA was used as a control. Cell-associated fluorescence was estimated by FACScan analyses. The inhibition curves are expressed as percent of maximal Alexa Fluor 488 SAA uptake in cells incubated in the absence of unlabeled competitor. The data (mean ± S.D.) represent one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results and were performed with triplicate determinations.

SAA-induced Secretion of IL-8 Is Increased in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 Cells

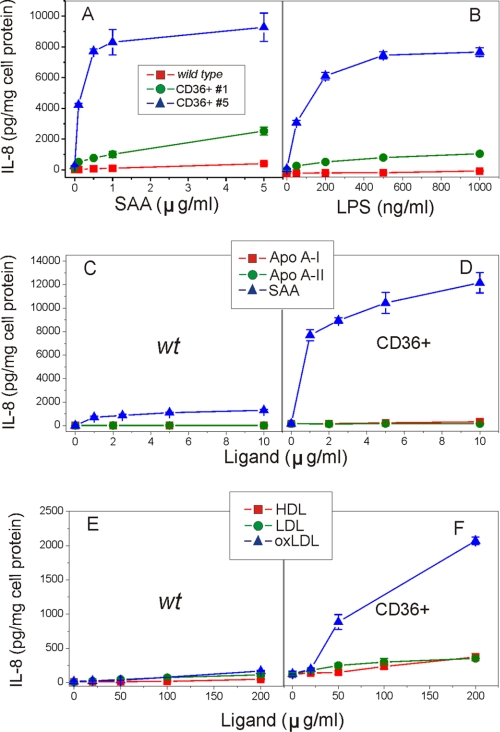

SAA induces secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in cultured human phagocytic cells such as neutrophils (24, 69) and THP-1 cells (5, 32). Our previous study demonstrated that some SAA effects can be associated with CLA-1 activity (34). To evaluate if CD36-mediated SAA uptake can induce increased cytokine production, levels of IL-8 secretion were assessed in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells upon stimulation with increasing doses of SAA (0–5 μg/ml). After a 20-h treatment with SAA, we observed a 5–10-fold increase of IL-8 release in the CD36-overexpressing clone having a low CD36 expression. A more dramatic increase (50–100-fold) was detected in the clone with high CD36 expression, when compared with WT control (Fig. 4A). A similar dose-dependent increase in IL-8 secretion levels was observed in both CD36-expressing clones versus control cells upon LPS treatment (Fig. 4B), previously shown to be capable of inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production via the CD36 receptor (55). We further tested whether other CD36 ligands, including native and modified lipoproteins, as well as apolipoproteins such as apoA-I and apoA-II, were capable of initiating pro-inflammatory response through CD36. Our results presented in Fig. 4, C–F, demonstrate that of all ligands tested only oxLDL induced dose-dependent IL-8 secretion, a response that was 5–7 times higher in CD36-overexpressing cells compared with control cells. This observation is consistent with the earlier report of Rahaman et al. (46) who demonstrated oxLDL-induced signaling via a CD36-dependent pathway in macrophages. In contrast, cell stimulation with native LDL or HDL as well as apoA-I and apoA-II did not have any effect (Fig. 4, C–F).

FIGURE 4.

Dose-dependent IL-8 secretion induced by various CD36 ligands in CD36-overexpressing and WT HEK293 cells. Control WT cells and two clones of HEK293 cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of SAA (A) or LPS (B) for 20 h. Control WT cells (C and E) and clone 5 (D and F) of HEK293 cells were incubated with increasing doses of apolipoproteins apoA-I, apoA-II, or SAA (0–10 μg/ml) or lipoproteins (0–200 μg/ml) for 20 h. IL-8 levels were determined in cell culture supernatants. Data represent one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results.

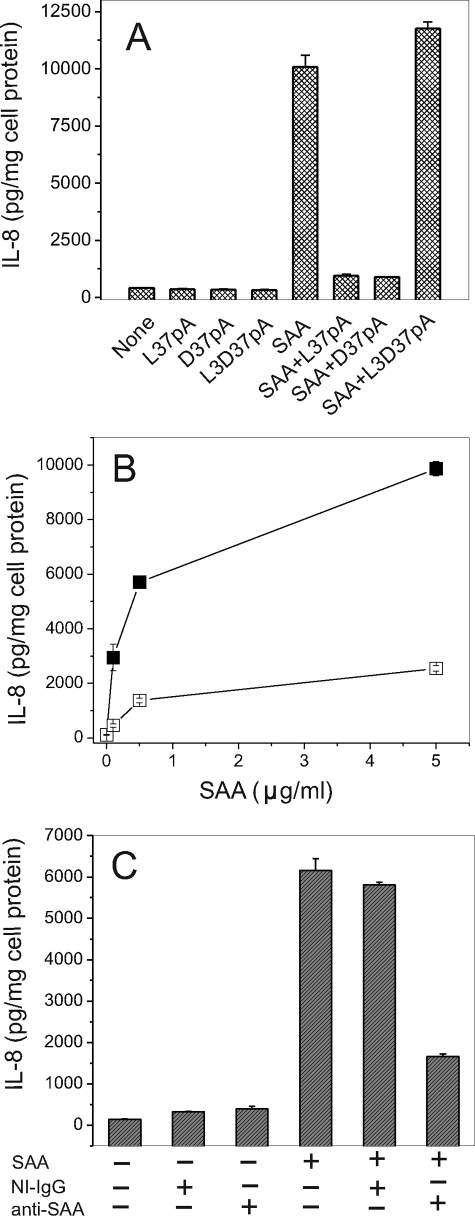

The amphipathic α-helical motif containing peptides, L-37pA and D-37pA, known CD36 ligands (55), efficiently blocked SAA-stimulated IL-8 release in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells (Fig. 5A). L3D-37pA peptide, containing three d-amino acid substitutions, known to disturb the amphipathic α-helical motif, did not affect SAA-induced IL-8 secretion. The SAA ability to induce cytokine release was reduced upon heat denaturation (100 °C for 25 min) by 75–85% (Fig. 5B), indicating that the effect was not due to contamination with endotoxin, which is known to retain its activity in these conditions. Similarly, anti-SAA antibody reduced SAA-stimulated IL-8 secretion by ∼75%, whereas the nonimmune IgG was without effect (Fig. 5C). In addition, LPS at a concentration of 0.5 ng/ml (the amount present in SAA at a concentration of 5 μg/ml) was unable to stimulate IL-8 release in HEK293 CD36-overexpressing cells (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Amphipathic α-helical peptides, heat treatment of SAA preparation, and anti-SAA-specific antibody reduce SAA-stimulated IL-8 release by HEK293 CD36-overexpressing cells. A, cells were pre-incubated with 10 μg/ml L-37pA, D-37pA, or L3D-37pA for 45 min prior to a 20-h SAA (1 μg/ml) treatment. B, cells were incubated for 20 h with increasing concentrations of intact (filled squares) or heat-treated (empty squares) (25 min at 100 °C) SAA. C, prior to SAA (1 μg/ml) addition, cells were pre-incubated for 45 min with either anti-SAA IgG or isotype-matched IgG at the same concentrations. IL-8 levels were determined in cell culture supernatants after 20 h.

Specific Binding of 125I-SAA Is Increased in CD36-overexpressing Versus Control Mock-transfected HeLa Cells

To further characterize CD36 as an SAA receptor, the ability of CD36- and mock-transfected HeLa cells to bind 125I-SAA was assessed. The control HeLa cell line demonstrated negligible or no 125I-SAA specific binding, although a marked increase in specific binding was observed after cell transfection with CD36. Scatchard analyses demonstrated that SAA bound to the CD36-overexpressing cells with Kd = 8.1 μg/ml, and the binding was saturable (Bmax = 0.8 μg/mg cell protein). Taking into consideration that in aqueous media SAA tends to form oligomeric complexes about the size of 300 kDa (70), Kd and Bmax values expressed in molar terms were 2.7 × 10−8 m and 2.7 nm/mg of cell protein, respectively.

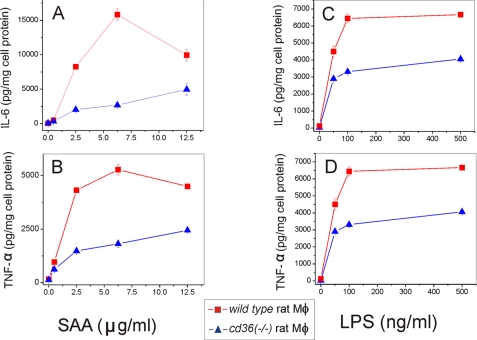

SAA- and LPS-induced Cytokine Production Is Significantly Impaired in Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages and Kupffer Cells Isolated from CD36-deficient Rat

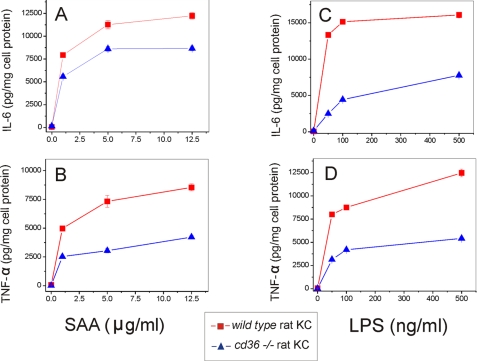

The role of CD36 role as a potential SAA receptor was tested further using cultured bone marrow-derived macrophages and liver KC, representing two types of macrophages, naturally expressing high levels of scavenger receptors, including CD36. Following a 20-h cell treatment with increasing concentrations of SAA or LPS, the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α secretion in normal cd36+/+ and cd36−/− rat macrophages and KC were determined. cd36−/− macrophages demonstrated significantly decreased levels of IL-6 (60–70% reduction) and TNF-α (40–60% reduction) upon SAA stimulation when compared with cd36+/+ macrophages (Fig. 6, A and B). Similar levels of cytokine production impairment occurred in the absence of a functional CD36 upon stimulation with LPS (Fig. 6, C and D) with markedly decreased (by at least 50%) levels of both cytokines. The levels of cytokine release upon SAA stimulation in cd36−/− KC were also reduced compared with the wild type KC, although the difference in IL-6 levels was less (30–35% reduction) than observed in macrophages (Fig. 7, A and B). This suggests the involvement of other receptors in SAA-induced cytokine production in these cells (35, 36). At the same time, LPS-stimulated levels of both cytokines in KC from CD36-null rats were significantly (by 60–65%) lower when compared with cd36+/+ cells (Fig. 7, C and D). These data indicate that along with other receptors, in particular TLRs (35, 36) and SR-BI (33, 34), CD36 significantly contributes to SAA- and LPS-induced pro-inflammatory signaling in phagocytic cells.

FIGURE 6.

Dose-dependent SAA- and LPS-induced secretion of IL-6 (A and B) and TNF-α (C and D) in cd36+/+ and cd36−/− rat macrophages. Cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of SAA or LPS for 20 h, and cytokine levels were determined in cell culture supernatants. The results are shown as means ± S.D. from duplicate measurements. Data are from one of the three separate experiments that yielded similar results.

FIGURE 7.

Dose-dependent SAA- and LPS-induced secretion of IL-6 (A and B) and TNF-α (C and D) in cd36+/+and cd36−/− rat Kupffer cells. Cells were exposed to increasing doses of SAA or LPS for 20 h, and cytokine levels were determined in cell culture supernatants. The results are shown as means ± S.D. from duplicate measurements. Data are from one of the two separate experiments that yielded similar results.

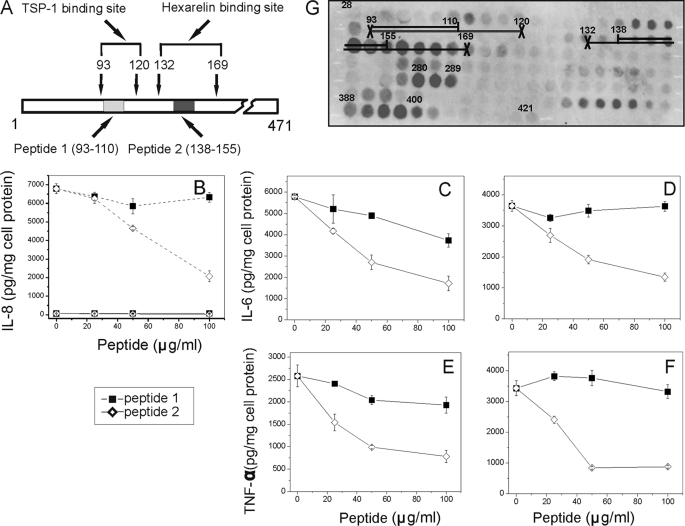

Effects of Synthetic Peptides Derived from CD36-binding Sites for TSP-1 and Hexarelin on SAA-stimulated IL-8 Release in HEK293 Cells and upon SAA- and LPS-induced Cytokine Secretion in Normal Rat Macrophages

To determine the CD36 domain responsible for SAA-dependent signaling, the ability of CD36-derived synthetic peptides (peptide 1 and peptide 2, Fig. 8A) having sequences based on the binding sites previously identified for CD36 ligands TSP-1 and hexarelin (71), respectively, to inhibit SAA- and LPS-induced cytokine release was tested. Fig. 8B demonstrates that SAA-stimulated IL-8 secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 was reduced by 40–70% with peptide 2 and was not affected by peptide 1, while wild type HEK 293 cells were unresponsive to SAA (1 μg/ml) stimulation. The blocking ability of both peptides upon SAA- and LPS-induced cytokine secretion was also tested in bone marrow-derived rat macrophages. As seen in Fig. 8, C–F, peptide 2 efficiently (by 70–75%) blocked both SAA- and LPS-stimulated secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α in a dose-dependent manner, whereas peptide 1 had a very weak inhibitory effect. Peptides at these concentrations were not cytotoxic as revealed by the lactate dehydrogenase release test (data not shown). These results suggest that SAA and LPS might share a common CD36-binding site that overlaps with the CD36-(Asn132–Met169) sequence previously identified as the binding domain for hexarelin (71).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of CD36-derived synthetic peptides upon SAA-stimulated IL-8 secretion in HEK293 cells and SAA- and LPS-induced cytokine production in bone marrow-derived rat macrophages. A, location of the binding sites for TSP-1 and hexarelin on the primary sequence of CD36. B, WT HEK293 (solid lines) and CD36-overexpressing (dashed lines) cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml of SAA (A) in the presence or absence of various concentrations of peptides for 20 h. C–F, normal bone marrow-derived macrophages were incubated with 2.5 μg/ml SAA (C and E) or 25 ng/ml LPS (D and F). After harvesting the media, IL-8 (A), IL-6 (C and D), and TNF-α (E and F) levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The data (mean ± S.D.) represent one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results. G, Pepscan image of SAA interaction with human CD36 extracellular domain epitopes. Reactivity of 132 20-mer overlapping peptides, spanning the amino acid sequence of the CD36 extracellular loop (aa residues 28–421), with Alexa Fluor 488 SAA was assessed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Sequences of the peptides within the regions with the most intensive fluorescent spots (145–166, 280–289, and 388–400) were identified as potential sites of SAA interaction with CD36. Numbers placed over the spots indicate the numbers of the first amino acids of the 20-mer peptide sequence.

Pepscan Analyses

To further identify potential SAA-binding sites within CD36, Pepscan analyses of the extracellular domain sequence were performed. The Pepscan results identified three potential SAA-binding sites that spanned the following amino acid sequences, 145–166, 280–289, and 388–400 (Fig. 8G). Only one binding site (sequences 145–166) completely coincided with the sequence of the hexarelin-binding site. The two other identified SAA-binding sequences within CD36 have never been reported. None of the SAA-binding sequences had any overlap with the TSP-binding site (sequences 93–120), whereas 30% overlapping could be seen between the oxLDL-binding site (sequences 155–183) and the 145–166 SAA-binding domain. The Pepscan results were consistent with our data demonstrating that CD36-derived peptide 2 (sequences 138–155), having homology with the 145–166 SAA-binding site, effectively blocked CD36-mediated activation by SAA, whereas peptide 1 (sequences 93–110) failed to block SAA-induced cytokine secretion in our experiments (Fig. 8, B–F).

Effects of MAPK and NF-κB Inhibitors on SAA-induced Cytokine Secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 Cells and Bone Marrow-derived Rat Macrophages

Cytokine production is known to be a distal event of the NF-κB and MAPK signaling cascades activated by numerous agents, including lipid-poor SAA (5, 24, 34, 35, 69). To test whether the increased IL-8 release induced by SAA in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells is associated with activation of NF-κB or any of the MAPKs, we used various pharmacological inhibitors known to selectively block these signaling pathways. Treatment of CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells with the specific MAPK inhibitors, PD98059, SB203580, or SP600125 that selectively block MEK1, the upstream kinase of ERK1/2, p38 kinase, and JNK kinase activity, respectively, resulted in a partial decrease of SAA-induced IL-8 secretion (Table 2). Although all MAPK inhibitors reduced IL-8 release to some extent, SP600125, a highly selective JNK1/2/3 inhibitor (72), was the most potent blocking agent of this process resulting in ∼60–65% inhibition. Three different NF-κB inhibitors were also tested for their ability to interfere with the cytokine release induced by SAA in HEK293 CD36-overexpressing cells. These cells have little or no expression of TLR2/4 receptors (66, 67), which are known to mediate ligand-induced signaling primarily via NF-κB activation (73), and recently have been proposed as novel receptors for SAA (35, 36). In contrast to MAPK inhibitors (Table 2), NF-κB inhibitors were less effective, as only a moderate (∼25%) inhibition of SAA-induced IL-8 secretion was observed with the highest dose of each of the NF-κB inhibitors used. These results provide indirect evidence that the CD36-mediated pro-inflammatory response induced by SAA in HEK293 cells predominantly involves activation of the JNK signaling pathway. To further assess the potential contribution of different signaling pathways to SAA-induced cytokine production, we compared the blocking potency of the MAPK inhibitors and the established NF-κB inhibitor, PDTC, on bone marrow-derived rat macrophages as a cell model with high expression of both TLR2/4 and CD36 receptors. The results from Table 3 demonstrate that all three MAPK inhibitors and PDTC strongly (by 75–85%) reduced IL-6 secretion in SAA-stimulated macrophages. This suggests that in macrophages, in contrast to HEK293 cells, activation of both MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways is required for the manifestation of the SAA-induced inflammatory response. The blocking activity of all tested inhibitors appeared to be comparable at their highest concentration (50 μm); however, we can not rule out the possibility of nonspecific inhibitory effects, due to their high concentrations, upon the activity of some other upstream kinases. At lower concentrations (within the range of 5–25 μm), MAPK inhibitors exhibited more significant inhibition (∼70–80%) on SAA-induced IL-6 release than did PDTC (∼45–60%).

TABLE 2.

Effects of NF-κB and MAPK inhibitors on SAA-induced IL-8 secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells

Data are presented as means ± S.D. of one of two separate experiments that were performed in duplicate and yielded similar results. IL-8 levels are expressed in nanograms per mg of cell protein.

| Inhibitora | IL-8 |

|---|---|

| ng/mg of cell protein | |

| SN50 inhibitor peptide | |

| 0 μm | 3.04 ± 0.188 |

| 5 μm | 3.33 ± 0.48 |

| 10 μm | 3.22 ± 0.52 |

| 25 μm | 2.32 ± 0.15b |

| Sulfasalasine | |

| 0 μm | 3.04 ± 0.188 |

| 0.1 mm | 3.41 ± 0.087 |

| 1 mm | 2.24 ± 0.126b |

| PDTC | |

| 0 μm | 6.68 ± 0.161 |

| 1 μm | 5.85 ± 0.245 |

| 5 μm | 5.42 ± 0.108b |

| 20 μm | 5.05 ± 0.131b |

| 50 μm | 7.15 ± 0.23 |

| PD98059 (MEK inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 3.72 ± 0.24 |

| 5 μm | 3.08 ± 0.015 |

| 20 μm | 2.77 ± 0.29b |

| 50 μm | 2.63 ± 0.138b |

| SB 203589 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 3.72 ± 0.24 |

| 1 μm | 2.93 ± 0.184b |

| 5 μm | 2.75 ± 0.27b |

| 25 μm | 2.29 ± 0.17b |

| SP600125 (JNK1/2/3 inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 3.72 ± 0.24 |

| 5 μm | 2.43 ± 0.26b |

| 20 μm | 1.34 ± 0.039b |

| 50 μm | 1.19 ± 0.62b |

a Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of inhibitors for 1 h prior to a 20-h stimulation with SAA (100 ng/ml).

b p < 0.05, IL-8 levels in the presence of inhibitor versus control (in the absence of inhibitor), Student's t test, are shown.

TABLE 3.

Effects of NF-κB and MAPK inhibitors on SAA-induced IL-6 secretion in rat bone marrow-derived macrophages

Data are presented as means ± S.D. of one of two separate experiments that were performed in duplicate and yielded similar results. IL-8 levels are expressed in nanograms per mg of cell protein.

| Inhibitora | IL-6 |

|---|---|

| ng/mg of cell protein | |

| PD98059 (MEK inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 16.8 ± 1.15 |

| 10 μm | 6.08 ± 0.21b |

| 25 μm | 3.95 ± 0.074b |

| 50 μm | 2.4 ± 0.118b |

| SB203589 (p38 MAPK inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 16.8 ± 1.15 |

| 5 μm | 15.69 ± 1.36 |

| 20 μm | 3.45 ± 0.49b |

| 50 μm | 2.18 ± 0.045b |

| SP600125 (JNK1/2/3 inhibitor) | |

| 0 μm | 16.8 ± 1.15 |

| 5 μm | 6.88 ± 0.32b |

| 10 μm | 4.4 ± 0.15b |

| 25 μm | 1.92 ± 0.15b |

| 50 μm | 1.26 ± 0.03b |

| PDTC | |

| 0 μm | 16.8 ± 1.15 |

| 5 μm | 8.91 ± 0.41b |

| 10 μm | 7.38 ± 0.088b |

| 25 μm | 6.84 ± 0.19b |

| 50 μm | 3.22 ± 0.34b |

a Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of inhibitors for 1 h prior to a 20-h stimulation with 2.5 μg/ml SAA.

b p < 0.05, IL-8 levels in the presence of inhibitor versus control (in the absence of inhibitor), Student's t test, are shown.

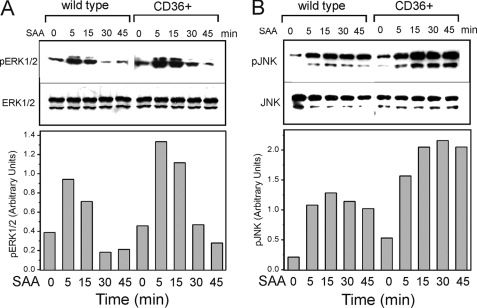

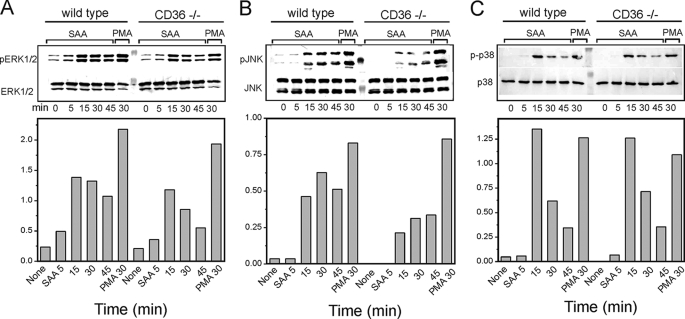

SAA-induced MAPK Activation Is Enhanced in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 Cells and Reduced in CD36-deficient Murine Macrophages

Previously, several receptors, including FPRL1, CLA-1, TLR2, and TLR4, have been demonstrated to contribute to SAA-induced MAPK-mediated signaling. To elucidate the role of CD36 in SAA-induced signaling mediated via the specific MAPK family members, we assessed the levels of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 phosphorylation in CD36-overexpressing and control HEK293 cells following SAA stimulation. Fig. 9 demonstrates elevated levels of ERK1/2 (∼1.5–1.8-fold; Fig. 9A) and JNK (∼1.5–2-fold; Fig. 9B) activation in CD36-overexpressing cells compared with wild type HEK293 cells after treatment with 1 μg/ml SAA for 5–45 min. At the same time, we did not observe any detectable levels of phosphorylated p38 in control or CD36-overexpressing cells in the presence or absence of SAA (data not shown). Next, we compared contribution of CD36 to activation of specific MAPKs by SAA in another cell model, murine macrophages from wild type and CD36-deficient mice. As shown in Fig. 10 upon cell treatment with SAA (0.5 μg/ml) for 0–45 min, all three MAPKs are transiently phosphorylated in both cell types; however, cd36−/− macrophages demonstrated markedly reduced levels of ERK1/2 (by 35–50%; Fig. 10A) and JNK phosphorylation (by 35–55%; Fig. 10B), when compared with cd36+/+ control cells, although no appreciable difference in p38 activation could be observed between the two cell types (Fig. 10C). Cell stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 30 min resulted in a pronounced activation of all three MAPKs tested with no significant difference between the two cell types.

FIGURE 9.

Immunoblot analyses of SAA-induced ERK1/2 (A) and JNK (B) MAPK phosphorylation in wild type and CD36-overexpressing HEK293. Cells were treated with 1 μg/ml SAA for the indicated time intervals. The expression of nonphosphorylated forms of MAPKs is shown as the loading control. The resulting bands were quantified using ImageJ image processing software (National Institutes of Health). The data are presented as the ratio of integral optic density for phosphorylated MAPK bands to the corresponding integral optic density values for total MAPK bands. The data represent one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results.

FIGURE 10.

Immunoblot analyses of SAA-induced ERK1/2 (A), JNK (B), and p38 (C) phosphorylation in wild type and cd36−/− murine macrophages. Cells were treated either with 0.5 μg/ml SAA for the indicated time intervals or with 25 ng/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 30 min. The expression of nonphosphorylated forms of MAPKs is shown as the loading control. The resulting bands were quantified using ImageJ image processing software. The data are presented as the ratio of integral optic density for phosphorylated MAPK bands to the corresponding integral optic density values for total MAPK bands. The data represent one of three separate experiments that yielded similar results.

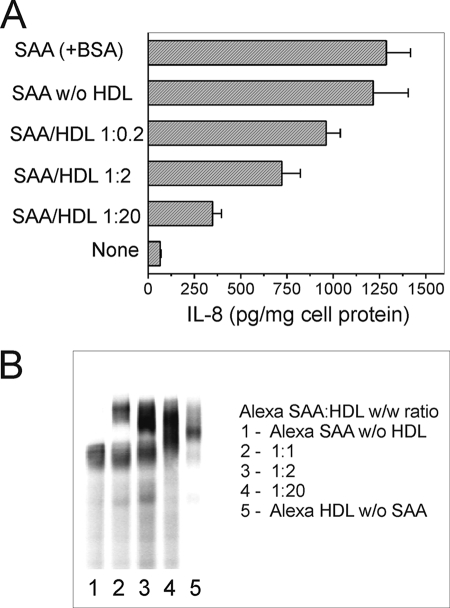

Effect of HDL-associated SAA on IL-8 Secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 Cells

The cytokine-stimulating activity of SAA associated with HDL was further assessed in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. As seen in Fig. 11A, the association of SAA with BSA did not have an effect on IL-8 secretion when compared with protein-free culture media. In contrast, SAA association with HDL markedly reduced its cytokine inducing activity in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. Nearly a 70% inhibition of IL-8 release, when compared with lipid-poor SAA, occurred upon cell stimulation with SAA·HDL complexes pre-formed at a protein ratio of 1:20 (w/w), which corresponds to the SAA/HDL ratio found in plasma upon moderate SAA increase observed in such clinical conditions as lupus erythematosus (74) or rheumatoid arthritis (75, 76). Of importance is that even with relatively moderately (∼10–20-fold) elevated plasma SAA (SAA/HDL (w/w) ratio ∼1:20), some portion of SAA could be found in a lipid-free form (Fig. 11B) that may account for the remaining cytokine inducing activity. An alternative explanation that the decrease of IL-8 release induced by SAA in the presence of HDL could be the result of the partially reduced cytokine inducing activity of SAA being in association with HDL seems less likely. It was previously reported that acute phase HDL are not capable of triggering pro-inflammatory cytokine release, indicating that cytokine inducing activity of SAA is completely lost when associated with HDL (24). An even more profound elevation (up to 100-fold) of SAA plasma levels, usually occurring during a strong APR, would result in a further increase of the SAA fraction not associated with lipoproteins. Our results confirm this suggestion, as up to 50% of Alexa-labeled SAA was detected not associated with HDL at a 1:1 (w/w) HDL/SAA protein ratio, as would be found in a strong APR, when the in vitro pre-formed SAA·HDL complexes were analyzed by nondenaturing PAGE (Fig. 11B). The presence of 1% FCS in the incubation media had little or no effect upon cytokine stimulating activity of SAA (data not shown), likely due to the low lipoprotein content of FCS and the absence of interference by other serum proteins.

FIGURE 11.

A, effects of the SAA·HDL complexes, pre-formed in vitro, on IL-8 secretion in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells. Cells were incubated with 5 μg/ml SAA, either lipoprotein-free or associated with HDL at various molar ratios (see “Experimental Procedures”) for 20 h, and IL-8 levels were determined in duplicate samples of cell culture supernatants. B, native PAGE of Alexa·SAA·HDL complexes. 10-μl aliquots containing 0.1 μg of Alexa-SAA, either HDL-free (lane 1) or pre-incubated with varying amounts of HDL (lanes 2–4), were analyzed in a 4–20% gradient gel under nondenaturing conditions. A sample containing 1 μg of Alexa-HDL was analyzed to determine the position of the SAA-free HDL (lane 5). Data from one of at least two representative experiments are shown.

DISCUSSION

Several receptors, including FPRL1, TLR2, and TLR4, have been implicated as mediators of SAA-induced pro-inflammatory activity in various immune cells (32, 35, 36, 69). We and others have demonstrated that scavenger receptor SR-BI/CLA-1 acts as an endocytic SAA receptor capable of mediating SAA-induced signaling (34) and acute phase HDL uptake (33). The CD36 receptor is structurally and functionally closely related to SR-BI. Both are trans-membrane glycoproteins with similar membrane topology, significant sequence homology (77, 78), and largely similar ligand binding specificity (49, 55, 59, 78, 79). The presence of amphipathic α-helices and/or negatively charged phospholipids appears to be a common feature shared by the majority of SR-BI and CD36 ligands, including apolipoproteins, anionic phospholipids, LPS, amphipathic helical peptides (34, 49, 59, 63), and lipoproteins (47, 48). However, no data have been reported on the possible role of CD36 as a receptor for SAA, an amphipathic helix containing proinflammatory acute phase apolipoprotein (3, 34). In this study, we investigated the ability of CD36 to bind SAA and mediate its cytokine-stimulating effects utilizing three cellular models, CD36-overexpressing epithelial cell lines, CD36-deficient rat bone marrow-derived macrophages, and liver Kupffer cells. Additionally, when assessing the role of CD36 in SAA-induced MAPK activation, we utilized macrophages isolated from the cd36−/− mice as an alternative model commonly used in CD36-related studies. This approach allowed us to study the role of CD36 as a binding and signaling receptor for SAA in cells with little or no expression of TLRs (HeLa (64) and HEK293 (66, 67) cell lines, also our data in Fig. 1B), as well as in phagocytic cells abundantly expressing TLRs and CD36. The results of our study provide new evidence that CD36 may function as a receptor for SAA, being involved in both its uptake and downstream signaling, as assessed by pro-inflammatory cytokine production. We have demonstrated that CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells have significantly enhanced (5–7-fold) Alexa Fluor 488 SAA uptake. The uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled lipoproteins and the amphipathic helical apolipoproteins A-I and A-II was also distinctly increased, whereas BSA and the L3D-37pA peptide, compounds lacking motifs recognized by CD36, were not taken up by mock-transfected or CD36-overexpressing cells. The results of the 125I-SAA binding assay further confirmed the role of CD36 as an SAA receptor. According to Scatchard analysis, SAA binds to CD36-overexpressing HeLa cells with relatively high affinity in a concentration-dependent and saturable manner. The binding parameters of the CD36-SAA interaction appeared to be comparable with those reported for other established CD36 ligands, including oxLDL, LDL, and HDL (65). The specificity of SAA binding with CD36 was additionally confirmed by competition studies. Ligands of CD36, such as HDL and the α-helical peptide L-37pA, blocked SAA uptake by 75 and 55%, respectively, indicating the presence of a common ligand-binding site for these agonists. oxLDL did not compete for SAA uptake in CD36-overexpressing cells, indicating that SAA does not interact with the oxLDL-binding site. Although Pepscan results pointed to a partial (∼30%) overlap between the SAA-binding domain and the oxLDL-binding sequence (155–183), apparently it is insufficient for oxLDL competition for SAA binding.

Substantially (10–50 times) higher SAA-induced IL-8 secretion was observed in CD36-transfected HEK293 cells when compared with wild type cells, which normally express very low CD36 levels. It is important to note that other CD36 ligands tested, in particular apoA-I, apoA-II, native LDL, and HDL, demonstrated little or no ability to induce cytokine production in CD36-overexpressing cells. One may speculate that the apolipoproteins apoA-I/II and unmodified lipoproteins such as LDL and HDL naturally function as CD36 antagonists preventing low grade inflammation induced by SAA or by low amounts of LPS, or other proinflammatory stimuli. Profound inhibition of SAA activity could be produced by the amphipathic α-helical peptides L-37pA and D-37pA, previously identified by us as high affinity CD36 ligands capable of blocking strong pro-inflammatory signaling induced by LPS and Escherichia coli (55). A similar amphipathic helical peptide D-4F was demonstrated to prevent development of atherosclerotic lesions in LDLR−/− and apoE−/− transgenic mice (80). It would be interesting to test if such peptides could prevent SAA accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions, a process recently reported for apoE−/− and LDLR−/− mice (81).

Using an alternative loss-of-function approach, we further confirmed a major role of CD36 in SAA-initiated pro-inflammatory signaling. The SAA-induced secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α was markedly reduced in cd36−/− rat macrophages compared with wild type cells. Although reduction of SAA-induced cytokine release was clearly observed in both types of CD36-deficient macrophages and Kupffer cells, the latter demonstrated a less pronounced decrease versus wild type cells, indicating involvement of other receptors, e.g. TLRs, as mediators of the cytokine-inducing effects of SAA.

In an attempt to define CD36-binding sites that could potentially interact with SAA and LPS, previously shown to be a CD36 ligand, we used synthetic peptides with amino acid sequences homologous to those previously identified as binding domains for two other known CD36 ligands, TSP-1 and hexarelin (71). While peptide 1 (identical to the 93–110 fragment of CD36 primary sequence) did not affect SAA-induced secretion of IL-8 in HEK293 CD36-overexpressing cells, peptide 2, homologous to 138–155 CD36 fragment localized within the hexarelin-binding site (Asn132–Met169), markedly inhibited CD36-dependent SAA-induced cytokine release (Fig. 8B). Similar peptide 1 results with very weak or no inhibitory activity along with a pronounced (up to 80%) dose-dependent inhibitory effect of peptide 2 upon SAA-induced cytokine secretion were obtained in experiments using bone marrow-derived rat macrophages. Furthermore, we demonstrated that LPS-stimulated cytokine release in macrophages is affected by treatment with peptide 1 or 2 in the same manner as SAA-induced cytokine release. These results suggest that both SAA and LPS interact with CD36 via a hexarelin-binding site, although not binding to the TSP-1-binding domain. Pepscan results also demonstrated that an SAA-binding site is located within the hexarelin-binding site. One of three domains of CD36 (spanning amino acids from 145 to 166) with the highest reactivity toward SAA encompassed a significant portion (∼60%) of the hexarelin-binding sequence as well as had overlap with the sequence of peptide 2. In contrast, no SAA binding activity was observed within the TSP-1-binding site (residues 93–120) homologous to synthetic peptide 1.

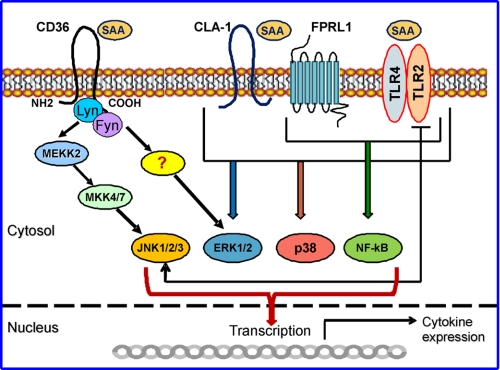

The role of CD36 as a cell surface receptor, binding a diverse set of ligands, has been recently extended to signal transduction. CD36 was shown to localize within the cholesterol-rich plasma membrane detergent-resistant microdomains, a location implicated in cell signaling and cholesterol transport (82, 83). Recent studies suggested that CD36 facilitates TLR2/TLR6-mediated signaling (42, 43, 54). Other data point to CD36 also functioning as a traditional signal transduction receptor capable of initiating signaling events upon ligand binding (44–46, 51). It was shown that the C-terminal domain of CD36 associates with the Src family member Lyn kinase and MEKK2, an upstream MAPK that regulates the JNK signaling pathway (46). Our previous data (55), obtained utilizing CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells expressing no TLR2 and relatively low levels of TLR4, indicates that CD36-mediated signaling initiated by E. coli and LPS, predominantly involves JNK activation and can proceed in the absence of functional TLRs. By utilizing specific signaling inhibitors, we demonstrated that SAA-induced cytokine production observed in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells was markedly inhibited by SP600125 (∼70%), a selective inhibitor of the JNK-mediated signaling cascade. In contrast, NF-κB inhibitors as well as blockers of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK demonstrated weak (∼25–30%) or no inhibition in these cells. Previous studies identified several receptors, including CLA-1, TLR2, TLR4, and FPRL1, as mediators of SAA-initiated signaling that engage MAPK signaling pathways (34–36, 69). Our results of the MAPK activation assays revealed direct involvement of CD36 in SAA-induced activation of 2 MAPK-ERK1/2 and JNK, as phosphorylation of both kinases was markedly increased as a result of CD36 overexpression in HEK293 cells. These results suggest that the enhanced SAA-stimulated IL-8 release observed in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells predominantly reflects increased ERK1/2 and JNK phosphorylation, whereas NF-κB activation, although generally required for IL-8 gene expression (84, 85), plays a less important role in the case of negligible TLRs expression. On the other hand, we have shown that SAA-initiated pro-inflammatory responses of macrophages, abundantly expressing both scavenger receptors and TLRs, are reduced to a similar extent in the presence of the NF-κB inhibitors and the inhibitors of all three signaling cascades involving ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPKs. These data are consistent with the results of previous reports demonstrating the activation of multiple signaling cascades, including NF-κB and MAPKs, as the prerequisite for SAA-induced pro-inflammatory signaling occurring in cells involved in the innate immune response, such as neutrophils (69) and macrophages (35). Upon further assessment of the SAA-induced MAPK activation in macrophages from wild type and CD36-deficient mice, we observed partially reduced (up to 50%) levels of ERK1/2 and JNK phosphorylation in cd36−/− cells. A schematic diagram of the SAA-induced signaling mediated by CD36 and other known SAA receptors is presented in Fig. 12. Although some of the previous reports characterized CD36 solely as an accessory protein facilitating TLR2/TLR6-mediated signaling (42, 43), our data obtained on CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells with no detectable TLR2 expression clearly indicates the independent role of CD36 in SAA-induced signal transduction via MAPK signaling cascades. We suggest that by analogy with other CD36 ligands, namely oxLDL, LPS, and bacteria, SAA binding to CD36 could also induce activation of the earlier identified CD36-associated signaling complex that contains Lyn and MEKK2 kinases (46) and regulates the JNK signaling pathway.

FIGURE 12.

Schematic diagram illustrating SAA-induced signaling mediated by CD36 and other known SAA receptors. TLR2, TLR4, FPRL1, and CLA-1 were identified as SAA receptors, mediating its signaling via the MAPK and/or NF-κB signaling pathways. CD36 is shown here as another novel SAA receptor that engages ERK1/2 and JNK signaling cascades upon SAA binding. In cells of the immune system (e.g. macrophages, dendritic cells, neutrophils, etc.) that express multiple SAA receptors, all signaling pathways could equally contribute to SAA-induced cytokine expression. In other cell types, such as epithelial cells, with low or negligible expression of TLR2/TLR4, CD36-dependent SAA-induced signaling via ERK1/2 and JNK-mediated pathways may play a predominant role in the pro-inflammatory cell response.

SAA is known to be carried in the plasma mainly as an apolipoprotein on HDL (1, 4–6). Because two previous reports demonstrated that SAA associated with HDL neutralized SAA as a chemoattractant (5) and lost its cytokine stimulating activity (24), we compared the cytokine-inducing potency of in vitro reconstituted SAA·HDL complexes as a function of the SAA/HDL ratio. The results of these experiments demonstrate that SAA being incorporated into HDL at a protein ratio 1:20 (w/w), equivalent to that found in plasma in such clinical conditions as rheumatoid arthritis (75, 76), was still capable of inducing cytokine release in CD36-overexpressing HEK293 cells, although the response was substantially (by 70%) reduced versus the cytokine levels induced by the lipid-free SAA. During the APR, when the serum concentration of SAA may reach levels up to 1000 μg/ml, the SAA/HDL protein ratio may shift toward 1:2–1:1.5 (w/w). Some portion (up to 15%) of the SAA during the LPS-induced APR in mice (86) can be found in a lipid-poor form and hence is able to induce pro-inflammatory responses, as demonstrated in our study (33) as well as by others (5, 35, 69). Significantly reduced (up to 90% or more) concentrations of HDL lipids and apolipoproteins in extravascular fluids, in particular lymph versus those measured in plasma (87, 88), could also create an environment more favorable for lipid-poor SAA formation. This aspect is particularly relevant because so many inflammatory conditions occur in extravascular environments. Additionally, SAA concentrations can be dramatically elevated locally due to local injury, inflammation, or infection (89). Considering that SAA synthesis may occur in several extrahepatic sites, including various cells of human atherosclerotic lesions, this may also contribute to high concentrations of lipid-poor SAA at the sites of inflammation (7, 89). Therefore, CD36 as a receptor able to potently mediate SAA-induced cytokine production and abundantly expressed in macrophages, known as critical effectors in inflammation and in atherosclerotic lesions, in particular, could certainly contribute to the pro-inflammatory environment at the atherosclerosis sites, as well as to the systemic inflammation, thus promoting atherosclerotic vascular disease.

In conclusion, our study identifies SAA as a novel ligand for the CD36 receptor, which is directly involved in SAA uptake and pro-inflammatory signaling. This finding, in addition to other recently reported receptors mediating SAA recognition and signaling, such as TLR2/4, FPRL1, and CLA-1, extends a network of SAA receptors facilitating activation of different signaling cascades, which can account for variable SAA phagocyte responses and specificity in different tissues/organs. The specificity of tissue/organ response might also be determined by the varying distribution of the network receptors among various phagocytic and epithelial cells. Our data demonstrating the inhibitory effect of a CD36-derived peptide, homologous to the hexarelin-binding domain of CD36, upon the SAA- and LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses, provide new insights into the mechanisms of the SAA/LPS interaction with CD36. Our results, especially those dealing with apolipoprotein mimetic peptides such as L-37pA and D-37pA, support the evaluation of therapeutic peptide interventions in the treatment of atherosclerosis (80, 90), rheumatoid arthritis (91), sepsis (59, 92), and other conditions (93).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. L. Vaisman and Dr. A. T. Remaley (NHLBI, National Institutes of Health) for the development, maintenance, and genotyping of a colony of CD36-null mice used in this study. We also thank Dr. Amar Marcelo (NHLBI, National Institutes of Health) for help with SAA labeling and Cornelio J. Duarte (NHLBI, National Institutes of Health) for lipoprotein preparation.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Programs of the Clinical Center, NIDDK, and NIAID.

- APR

- acute phase response

- HDL

- high density lipoprotein

- KC

- Kupffer cells

- LDL

- low density lipoprotein

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEK

- MAPK kinase

- oxLDL

- oxidized LDL

- PDTC

- pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

- SAA

- serum amyloid A

- WT

- wild type

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- FCS

- fetal calf serum

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- FACS

- fluorescence-activated cell sorter

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IL

- interleukin

- SR-BI

- scavenger receptor class B, type I

- TLR

- toll-like receptor

- TNF

- tumor necrosis factor

- hCD36

- human CD36.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kushner I., Rzewnicki D. L. (1994) Baillieres Clin. Rheumatol. 8, 513–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kushner I. (1982) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 389, 39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uhlar C. M., Whitehead A. S. (1999) Eur. J. Biochem. 265, 501–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malle E., Steinmetz A., Raynes J. G. (1993) Atherosclerosis 102, 131–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel H., Fellowes R., Coade S., Woo P. (1998) Scand. J. Immunol. 48, 410–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coetzee G. A., Strachan A. F., van der Westhuyzen D. R., Hoppe H. C., Jeenah M. S., de Beer F. C. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 261, 9644–9651 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meek R. L., Urieli-Shoval S., Benditt E. P. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 3186–3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urieli-Shoval S., Cohen P., Eisenberg S., Matzner Y. J. (1998) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46, 1377–1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang J. S., Sloane J. A., Wells J. M., Abraham C. R., Fine R. E., Sipe J. D. (1997) Neurosci. Lett. 225, 73–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumon Y., Suehiro T., Hashimoto K., Nakatani K., Sipe J. D. (1999) J. Rheumatol. 26, 785–790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pepys M. B., Baltz M. L. (1983) Adv. Immunol. 34, 141–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Husebekk A., Skogen B., Husby G., Marhaug G. (1985) Scand. J. Immunol. 21, 283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malle E., De Beer F. C. (1996) Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 26, 427–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fyfe A. I., Rothenberg L. S., DeBeer F. C., Cantor R. M., Rotter J. I., Lusis A. J. (1997) Circulation 96, 2914–2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambers R. E., MacFarlane D. G., Whicher J. T., Dieppe P. A. (1983) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 42, 665–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Hara R., Murphy E. P., Whitehead A. S., FitzGerald O., Bresnihan B. (2000) Arthritis Res. 2, 142–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leinonen E., Hurt-Camejo E., Wiklund O., Hultén L. M., Hiukka A., Taskinen M. R. (2003) Atherosclerosis 166, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jousilahti P., Salomaa V., Rasi V., Vahtera E., Palosuo T. (2001) Atherosclerosis 156, 451–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebeling P., Teppo A. M., Koistinen H. A., Viikari J., Rönnemaa T., Nissén M., Bergkulla S., Salmela P., Saltevo J., Koivisto V. A. (1999) Diabetologia 42, 1433–1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leinonen E. S., Hiukka A., Hurt-Camejo E., Wiklund O., Sarna S. S., Mattson Hultén L., Westerbacka J., Salonen R. M., Salonen J. T., Taskinen M. R. (2004) J. Intern. Med. 256, 119–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haffner S. M., Agostino R. D., Jr., Saad M. F., O'Leary D. H., Savage P. J., Rewers M., Selby J., Bergman R. N., Mykkänen L. (2000) Am. J. Cardiol. 85, 1395–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badolato R., Wang J. M., Murphy W. J., Lloyd A. R., Michiel D. F., Bausserman L. L., Kelvin D. J., Oppenheim J. J. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 203–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu L., Badolato R., Murphy W. J., Longo D. L., Anver M., Hale S., Oppenheim J. J., Wang J. M. (1995) J. Immunol. 155, 1184–1190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furlaneto C. J., Campa A. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 268, 405–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah C., Hari-Dass R., Raynes J. G. (2006) Blood 108, 1751–1757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husebekk A., Skogen B., Husby G. (1987) Scand. J. Immunol. 25, 375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kisilevsky R., Subrahmanyan L. (1992) Lab. Invest. 66, 778–785 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stonik J. A., Remaley A. T., Demosky S. J., Neufeld E. B., Bocharov A., Brewer H. B. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321, 936–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steinmetz A., Hocke G., Saïle R., Puchois P., Fruchart J. C. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1006, 173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liang J. S., Sipe J. D. (1995) J. Lipid Res. 36, 37–46 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su S. B., Gong W., Gao J. L., Shen W., Murphy P. M., Oppenheim J. J., Wang J. M. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 189, 395–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee H. Y., Kim M. K., Park K. S., Bae Y. H., Yun J., Park J. I., Kwak J. Y., Bae Y. S. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330, 989–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Westhuyzen D. R., Cai L., de Beer M. C., de Beer F. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35890–35895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baranova I. N., Vishnyakova T. G., Bocharov A. V., Kurlander R., Chen Z., Kimelman M. L., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Thomas F., Eggerman T. L., Patterson A. P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8031–8040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng N, He R., Tian J., Ye P. P., Ye R. D. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 22–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandri S., Rodriguez D., Gomes E., Monteiro H. P., Russo M., Campa A. (2008) J. Leukocyte Biol. 83, 1174–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krieger M., Acton S., Ashkenas J., Pearson A., Penman M., Resnick D. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 4569–4572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson A. M. (1996) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 8, 20–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muzio M., Natoli G., Saccani S., Levrero M., Mantovani A. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 2097–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Faure E., Equils O., Sieling P. A., Thomas L., Zhang F. X., Kirschning C. J., Polentarutti N., Muzio M., Arditi M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 11058–11063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guha M., Mackman N. (2001) Cell. Signal. 13, 85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoebe K., Georgel P., Rutschmann S., Du X., Mudd S., Crozat K., Sovath S., Shamel L., Hartung T., Zähringer U., Beutler B. (2005) Nature 433, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Triantafilou M., Gamper F. G., Haston R. M., Mouratis M. A., Morath S., Hartung T., Triantafilou K. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31002–31011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiménez B., Volpert O. V., Reiher F., Chang L., Muñoz A., Karin M., Bouck N. (2001) Oncogene 20, 3443–3448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore K. J., El Khoury J., Medeiros L. A., Terada K., Geula C., Luster A. D., Freeman M. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47373–47379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahaman S. O., Lennon D. J., Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., Hazen S. L., Silverstein R. L. (2006) Cell Metab. 4, 211–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Febbraio M., Hajjar D. P., Silverstein R. L. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 785–791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Endemann G., Stanton L. W., Madden K. S., Bryant C. M., White R. T., Protter A. A. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 11811–11816 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rigotti A., Acton S. L., Krieger M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16221–16224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dawson D. W., Pearce S. F., Zhong R., Silverstein R. L., Frazier W. A., Bouck N. P. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 138, 707–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Medeiros L. A., Khan T., El Khoury J. B., Pham C. L., Hatters D. M., Howlett G. J., Lopez R., O'Brien K. D., Moore K. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10643–10648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savill J., Hogg N., Ren Y., Haslett C. (1992) J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1513–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Philips J. A., Rubin E. J., Perrimon N. (2005) Science 309, 1251–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stuart L. M., Deng J., Silver J. M., Takahashi K., Tseng A. A., Hennessy E. J., Ezekowitz R. A., Moore K. J. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 170, 477–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baranova I. N., Kurlander R., Bocharov A. V., Vishnyakova T. G., Chen Z., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Patterson A. P., Eggerman T. L. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 7147–7156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schulthess G., Compassi S., Werder M., Han C. H., Phillips M. C., Hauser H. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 12623–12631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merrifield R. B. (1969) JAMA 210, 1247–1254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fairwell T., Hospattankar A. V., Brewer H. B., Jr., Khan S. A. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 4796–4800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Vishnyakova T. G., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Thomas F., Patterson A. P., Eggerman T. L. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36072–36082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kunjathoor V. V., Febbraio M., Podrez E. A., Moore K. J., Andersson L., Koehn S., Rhee J. S., Silverstein R., Hoff H. F., Freeman M. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49982–49988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smedsrød B., Pertoft H., Eggertsen G., Sundström C. (1985) Cell Tissue Res. 241, 639–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zaĭtseva E. V., Khung Veĭ Vishniakova T. G., Frolova E. G., Repin V. S., Bocharov A. V. (1994) Biull. Eksp. Biol. Med. 117, 268–270 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vishnyakova T. G., Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Chen Z., Remaley A. T., Csako G., Eggerman T. L., Patterson A. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 22771–22780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wyllie D. H., Kiss-Toth E., Visintin A., Smith S. C., Boussouf S., Segal D. M., Duff G. W., Dower S. K. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 7125–7132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brandenburg L. O., Koch T., Sievers J., Lucius R. (2007) J. Neurochem. 101, 718–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gon Y., Asai Y., Hashimoto S., Mizumura K., Jibiki I., Machino T., Ra C., Horie T. (2004) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 31, 330–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lepper P. M., Triantafilou M., Schumann C., Schneider E. M., Triantafilou K. (2005) Cell Microbiol. 7, 519–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calvo D., Gómez-Coronado D., Suárez Y., Lasunción M. A., Vega M. A. (1998) J. Lipid Res. 39, 777–788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.He R., Sang H., Ye R. D. (2003) Blood 101, 1572–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kinkley S. M., Bagshaw W. L., Tam S. P., Kisilevsky R. (2006) Amyloid 13, 123–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demers A., McNicoll N., Febbraio M., Servant M., Marleau S., Silverstein R., Ong H. (2004) Biochem. J. 382, 417–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bennett B. L., Sasaki D. T., Murray B. W., O'Leary E. C., Sakata S. T., Xu W., Leisten J. C., Motiwala A., Pierce S., Satoh Y., Bhagwat S. S., Manning A. M., Anderson D. W. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 13681–13686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doyle S. L., O'Neill L. A. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 72, 1102–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maury C. P., Teppo A. M., Wegelius O. (1982) Ann. Rheum. Dis. 41, 268–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cunnane G., Grehan S., Geoghegan S., McCormack C., Shields D., Whitehead A. S., Bresnihan B., Fitzgerald O. (2000) J. Rheumatol. 27, 58–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Benson M. D., Cohen A. S. (1979) Arthritis Rheum. 22, 36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Greenwalt D. E., Lipsky R. H., Ockenhouse C. F., Ikeda H., Tandon N. N., Jamieson G. A. (1992) Blood 80, 1105–1115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Acton S. L., Scherer P. E., Lodish H. F., Krieger M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 21003–21009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vishnyakova T. G., Kurlander R., Bocharov A. V., Baranova I. N., Chen Z., Abu-Asab M. S., Tsokos M., Malide D., Basso F., Remaley A., Csako G., Eggerman T. L., Patterson A. P. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16888–16893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Navab M., Anantharamaiah G. M., Hama S., Garber D. W., Chaddha M., Hough G., Lallone R., Fogelman A. M. (2002) Circulation 105, 290–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.O'Brien K. D., McDonald T. O., Kunjathoor V., Eng K., Knopp E. A., Lewis K., Lopez R., Kirk E. A., Chait A., Wight T. N., deBeer F. C., LeBoeuf R. C. (2005) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 785–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schnitzer J. E., Oh P., McIntosh D. P. (1996) Science 274, 239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Babitt J., Trigatti B., Rigotti A., Smart E. J., Anderson R. G., Xu S., Krieger M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13242–13249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hoffmann E., Dittrich-Breiholz O., Holtmann H., Kracht M. (2002) J. Leukocyte Biol. 72, 847–855 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Roebuck K. A. (1999) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 19, 429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cabana V. G., Feng N., Reardon C. A., Lukens J., Webb N. R., de Beer F. C., Getz G. S. (2004) J. Lipid Res. 45, 317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sloop C. H., Dory L., Krause B. R., Castle C., Roheim P. S. (1983) Atherosclerosis 49, 9–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nanjee M. N., Cooke C. J., Olszewski W. L., Miller N. E. (2000) J. Lipid Res. 41, 1317–1327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meek R. L., Eriksen N., Benditt E. P. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 7949–7952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]