Crystal structures of ModA from M. acetivorans in the apo and ligand-bound conformations confirm domain rotation upon ligand binding.

Keywords: ModA, molybdate, Methanosarcina acetivorans, periplasmic binding proteins

Abstract

The trace-element oxyanion molybdate, which is required for the growth of many bacterial and archaeal species, is transported into the cell by an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily uptake system called ModABC. ModABC consists of the ModA periplasmic solute-binding protein, the integral membrane-transport protein ModB and the ATP-binding and hydrolysis cassette protein ModC. In this study, X-ray crystal structures of ModA from the archaeon Methanosarcina acetivorans (MaModA) have been determined in the apoprotein conformation at 1.95 and 1.69 Å resolution and in the molybdate-bound conformation at 2.25 and 2.45 Å resolution. The overall domain structure of MaModA is similar to other ModA proteins in that it has a bilobal structure in which two mixed α/β domains are linked by a hinge region. The apo MaModA is the first unliganded archaeal ModA structure to be determined: it exhibits a deep cleft between the two domains and confirms that upon binding ligand one domain is rotated towards the other by a hinge-bending motion, which is consistent with the ‘Venus flytrap’ model seen for bacterial-type periplasmic binding proteins. In contrast to the bacterial ModA structures, which have tetrahedral coordination of their metal substrates, molybdate-bound MaModA employs octahedral coordination of its substrate like other archaeal ModA proteins.

1. Introduction

Climate change and global warming have recently reached the forefront of scientific, social and political concerns, spurring a renewed search for alternative fuels and more efficient uses of natural resources. Methane is one of the main greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere, largely via methanogenesis, a biological process that is carried out exclusively by methanogenic archaea (Galagan et al., 2002 ▶; Gribaldo & Brochier-Armanet, 2006 ▶). The efficient harvesting and recycling of this abundant gas for alternative fuel-production purposes may prove one viable means of reducing global warming. In natural habitats, the majority of biologically synthesized methane (approximately 60%) is derived from the conversion of acetate to CH4 and CO2 (Zinder, 1993 ▶; Galagan et al., 2002 ▶). The metabolically and environmentally versatile model methanogen Methanosarcina acetivorans is able to utilize acetate as well as a variety of one-carbon substrates including methanol and trimethyl, dimethyl and monomethyl amines. It displays the largest archaeal genome, containing 4528 ORFs within its 5.75 Mb (Galagan et al., 2002 ▶), and offers insight into the unique metabolic pathways that are needed for methane synthesis (Oelgeschlager & Rother, 2008 ▶). Ultimately, determining which specific proteins and metabolic pathways render this organism and others in its genus so well suited to methane synthesis could lead to their exploitation as energy sources.

M. acetivorans was isolated from a marine canyon, where acetate is normally expected to be utilized mainly for sulfate reduction (Sowers et al., 1984 ▶). Molybdate uptake may be a key factor in the survival of M. acetivorans in this habitat. It has been demonstrated that the addition of molybdate to a solution of acetate prevented sulfate reducers from accumulating acetate, allowing methanogens to outcompete sulfate reducers in acetate acquisition (Scholten et al., 2000 ▶). Molybdate is an essential metal in the biochemical conversion of acetate plus all other known methanogenic substrates to methane. Key enzymes in M. acetivorans include the molybdenum-type formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase involved in electron transfer and CO2 formation and the molybdenum-type nitrogenase used for nitrogen fixation (Galagan et al., 2002 ▶).

In Escherichia coli, molybdate uptake is accomplished by the high-affinity molybdate-transport system encoded by the modABCD operon. The protein components include ModA, the molybdate-binding protein located in the periplasmic space, ModB, a transmembrane protein that provides the substrate-translocation pathway across the cell membrane, and ModC, an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) protein associated with the cytoplasmic face of ModB that couples ATP hydrolysis to transport of the substrate (Maupin-Furlow et al., 1995 ▶). The function of the fourth protein in the operon, ModD, is unclear and it is not essential for molybdate transport (Maupin-Furlow et al., 1995 ▶). ModA-type proteins are ubiquitously present in bacteria and archaea (Balan et al., 2008 ▶) and there are multiple operons in the M. acetivorans genome that have been annotated as molybdate-transport systems, although only the ModBC complex (MaModBC) encoded by the MA0281/MA0282 genes has been characterized. The crystal structure of MaModBC has been determined and the ability of the oxyanions molybdate and tungstate to inhibit substrate uptake has been demonstrated (Gerber et al., 2008 ▶). The MA0281/MA0282 genes are preceded by a gene (MA0280) which encodes a protein annotated as a putative molybdate substrate-binding protein. While there are no experimental results addressing the physiological ligand of any of the archaeal ModA proteins, the evidence points toward the MA0280/MA0281/MA0282 system being an oxyanion-transport system for molybdate or tungstate.

The molybdate-bound bacterial ModA structures from E. coli (Hu et al., 1997 ▶), Azotobacter vinelandii (Lawson et al., 1998 ▶) and Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri (Balan et al., 2008 ▶) have been solved and show a high degree of tertiary structure conservation, as well as a lesser but still remarkable degree of similarity in hydrogen-bonding interactions in the anion-binding site. A recent study that determined the structure of five archaeal ModA homologues bound to the molybdate analog tungstate, including the M. acetivorans ModA encoded by MA0280, has revealed that archaeal ModA proteins employ octahedral coordination of their metal substrates, in contrast to the tetrahedral coordination seen in bacterial proteins (Hollenstein et al., 2009 ▶). Information on the mechanism by which molybdate is transported across the cell membrane has been derived from the structures of the archaeal Archaeoglobus fulgidus ModA, which has been crystallized in molybdate and tungstate-bound conformations and as a complex of tungstate-bound ModA with the A. fulgidus ModBC molybdate transporter (Hollenstein et al., 2007 ▶).

Here, we present high-resolution crystal structures of the M. acetivorans MA0280 ModA protein (MaModA) in both the apo and the molybdate-bound forms. Comparison of the apo and bound structures reveals the large conformational change that must occur upon ligand binding and confirms that MaModA binds substrate through a hinge-bending motion that rotates the two lobes of the protein towards each other. Comparison of molybdate-bound MaModA with previously solved archaeal ModA structures (Hollenstein et al., 2007 ▶, 2009 ▶), including tungstate-bound MaModA, confirms that molybdate binding occurs through octahedral coordination of the substrate.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Expression and purification of M. acetivorans ModA

MaModA (MA0280) was amplified from M. acetivorans C2A genomic DNA using forward (5′-GGGGCCATGGCTGATAACCAGCCAGAGCCCGGGAATACC) and reverse (5′-GGGGGCGGC CGC ATTATACTACAAGGGCCTGCAATTCTTCAGGCATTGAG) primers that incorporated NcoI and NotI restriction-enzyme sites (bold), respectively. The forward primer was designed to omit the N-terminal 26 amino acids, which contain a signal sequence for protein secretion across the cytoplasmic membrane (amino acids 1–23) and a putative lipoprotein-attachment site (Cys25), while the reverse primer contained the native stop codon (italic). The PCR amplicon was cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and subcloned into the pETM-11 expression vector (Pinotsis et al., 2006 ▶) which appended the encoded N-terminal sequence MKHHHHHHPMSDYDIPTTENLYFEGAMA, which includes a hexahistidine tag for affinity purification and a TEV protease sequence for removal of the N-terminal tag. Nucleotide sequencing confirmed that the MaModA gene sequence was intact and in frame.

MaModA was expressed in E. coli BL21-Gold (DE3) cells (Stratagene) grown in 4×YT medium buffered with MOPS pH 7.0 and supplemented with kanamycin (20 µg ml−1). Protein expression was induced by the addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM and the growth temperature was reduced from 310 to 298 K. Cells were harvested after 4 h by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer [20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol, 0.2 µg ml−1 lysozyme, 2 µg ml−1 DNase I and 1:100 protease-inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich)] and lysed at 20.7 MPa using a French pressure cell. The cell lysate was loaded onto Ni–NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen) pre-equilibrated in binding buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol) and washed sequentially with one column volume each of binding buffer, high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol) and imidazole wash buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 50 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol). The protein was eluted with buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 10% glycerol. The protein was further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 75 HiLoad 16/60 Prep Grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in storage buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol). Peak fractions containing MaModA were pooled and concentrated. The molecular weight of the recombinant protein and the purity of the sample were confirmed by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. The hexahistidine tag was not removed for subsequent studies.

2.2. Crystallization

Initial crystallization trials were carried out using the sitting-drop and hanging-drop vapor-diffusion methods with commercially available crystallization screens from Hampton Research and Emerald BioSystems. Drops containing 1 µl protein stock solution (16–23 mg ml−1) and 1 µl reservoir solution were equilibrated against 100 µl reservoir solution at room temperature for apo MaModA and at 293 K for cocrystallization experiments. Crystal optimization was performed by varying the pH, the precipitant concentration and the ratio of protein stock to reservoir solution volume.

2.2.1. Crystallization of the apo structure and preparation of caesium-soaked crystals for phasing

Initial crystals that diffracted X-rays to 3.53 Å resolution were obtained at room temperature from condition No. 21 (1.8 M ammonium citrate pH 7.0) of Index Screen (Hampton Research). Optimization of the crystallization conditions yielded octahedral and pentagonal bipyramidal crystals that formed when 1 µl purified protein solution (21–23 mg ml−1) was mixed with 1 µl reservoir solution (1.4 M ammonium citrate pH 6.4 or 1.4 M ammonium citrate pH 6.0, 4 mM sodium sulfate) and equilibrated over a 100 µl reservoir at 293 K. Crystals grew within a week and were cryoprotected by soaking them in reservoir solution containing 20% glycerol for 30 s. The crystals were found to diffract to maximum resolutions of 1.95 and 1.69 Å for the two different reservoir solutions, respectively. Structural and refinement statistics are outlined in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for MaModA.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| PDB code | 3k6u | 3k6v | 3k6w | 3k6x | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conformation | Open | Open | Apo, low resolution | Apo, high resolution | Ligand-bound crystal form I | Ligand-bound crystal form II |

| Active-site ligand | N/A | N/A | None | Citrate | Molybdate | Molybdate |

| Data-collection temperature (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Other ligands | Iodide | Caesium | None | None | Sulfates | Sulfates |

| Data-collection statistics | ||||||

| Resolution (Å) | 90.00–2.70 | 80.00–3.05 | 90.00–1.95 | 90.00–1.69 | 90.00–2.45 | 90.00–2.25 |

| Space group | P61 | P61 | P61 | P61 | C2 | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters | ||||||

| a (Å) | 81.74 | 81.22 | 82.18 | 81.63 | 94.51 | 147.20 |

| b (Å) | 81.74 | 81.22 | 82.18 | 81.63 | 66.12 | 65.59 |

| c (Å) | 105.245 | 105.289 | 104.94 | 104.64 | 61.46 | 94.77 |

| β (°) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 95.99 | 123.95 |

| Radiation source | ALS 8.2.2 | Rigaku FR-D | ALS 8.2.2 | ALS 8.2.2 | ALS 8.2.2 | ALS 8.2.2 |

| Radiation wavelength (Å) | 1.459 | 1.542 | 0.954 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Measured reflections | 195952 | 163394 | 319700 | 492267 | 45594 | 78398 |

| Unique reflections | 21339 | 14879 | 29447 | 84835 | 13167 | 72180 |

| Completeness (%) | 100.0 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.0) | 99.9 (100.0) | 96.9 (82.3) | 93.7 (91.4) | 87.8 (84.7) |

| Rmerge† | 0.114 (0.617) | 0.110 (0.453) | 0.079 (0.468) | 0.040 (0.472) | 0.071 (0.431) | 0.045 (0.279) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 19.5 (5.9) | 19.5 (5.4) | 22.5 (10.4) | 32.7 (2.3) | 12.5 (2.0) | 12.7 (2.1) |

| Riso/high-resolution limit (Å) | 0.192/2.6 | 0.173/2.9 | ||||

| Phase determination | ||||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 20–2.50 | 20–2.94 | ||||

| RCullis‡ (isomorphous, acentric/centric) (%) | 83/84 | 98/98 | ||||

| RCullis§ (anomalous) (%) | 95 | 98 | ||||

| Phasing power¶ (acentric/centric) | 1.22/0.89 | 0.25/0.22 | ||||

| No. of sites | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Mean overall figure of merit (before/after DM) | 0.3685/0.6170 | |||||

| Refinement statistics | ||||||

| Rwork†† (%) | 17.6 | 18.9 | 20.6 | 23.6 | ||

| Rfree‡‡ (%) | 20.8 | 21.1 | 22.8 | 27.2 | ||

| No. of residues (protein/water) | 312/176 | 312/295 | 312/28 | 322 × 2/95 | ||

| R.m.s.d. bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.008 | ||

| R.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 1.392 | 0.975 | 1.727 | 1.714 | ||

R

merge(I) =

.

.

R

Cullis =

, where ∊ is the lack of closure.

, where ∊ is the lack of closure.

R

Cullis =

, where ∊ is the lack of closure.

, where ∊ is the lack of closure.

Phasing power = 〈F H/∊〉.

R

work =

.

.

R

free =

, where all reflections belong to a test set of 5% randomly selected data.

, where all reflections belong to a test set of 5% randomly selected data.

Attempts at molecular replacement using the E. coli ModA homolog (PDB code 1amf; Hu et al., 1997 ▶) failed and the structures of the archaeal ModA homologues were not available when this study was performed. Therefore, heavy-atom soaking experiments were conducted in order to obtain phase information. Native crystals grown in a slightly different reservoir solution (1.6 M ammonium citrate pH 6.4) were soaked in iodide and caesium to obtain phase information for isomorphous replacement and for structure solution of the apo form of MaModA. Crystals were separately soaked in an iodide-containing cryosolution [1.6 M ammonium citrate pH 7.0, 18%(v/v) glycerol and 0.36 M potassium iodide] and a caesium-containing cryosolution [1.6 M ammonium citrate pH 7.0, 18%(v/v) glycerol, 0.48 M caesium chloride] for 30 s and 18 min, respectively, before being flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen for X-ray diffraction analysis.

2.2.2. Cocrystallization of MaModA with molybdate

In contrast to the results of cocrystallization experiments with bacterial ModA homologues (Hu et al., 1997 ▶; Lawson et al., 1998 ▶), our initial attempts to cocrystallize the archaeal MaModA MA0280 protein with molybdate failed when using a fourfold to sevenfold molar excess of molybdate in crystal-soaking experiments. In search of the optimal molybdate concentration for cocrystallization, differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) was employed to screen for concentrations of molybdate that would increase the thermal stability of MaModA. DSF experiments were carried out as described by Vedadi et al. (2006 ▶). Briefly, purified MaModA at 50 µM was incubated with various concentrations of sodium molybdate (up to 1.5 M), the protein was heated from 298 to 368 K in 1 K intervals and the fluorescence signal was measured using a Mx3000P QPCR machine (Stratagene).

MaModA at 32 mg ml−1 in storage buffer was diluted to 16 mg ml−1 by the addition of an equal volume of storage buffer containing 500 mM sodium molybdate and incubated for 15 min at 277 K. The molybdate-containing protein stock was screened using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method and commercially available screens from Hampton Research and Emerald BioSystems. For each condition, three 150 nl crystal drops were set up using different protein:reservoir solution ratios of 130:20, 75:75 and 20:130 nl and equilibrated against 100 µl reservoir solution. Crystals observed in the 1:1 protein:reservoir solution drop with condition No. 5 of Hampton Crystal Screen 2 [2.0 M ammonium sulfate, 5%(v/v) 2-propanol] were optimized by varying the ammonium sulfate and 2-propanol concentrations. The crystals that yielded the molybdate-bound structures were grown using the hanging-drop method by mixing 113 nl protein solution with 113 nl reservoir solution and equilibrating against 100 µl reservoir solution at 293 K using 43 mg ml−1 protein diluted twofold as previously described. The final reservoir compositions were 2.1 M ammonium sulfate and either 1%(v/v) or 3%(v/v) 2-propanol (crystal form I) and 2.4 M ammonium sulfate, 4%(v/v) 2-propanol (crystal form II). Molybdate-bound ModA crystals were cryoprotected by soaking the crystals in reservoir solution containing 25% glycerol for 30 s.

2.3. Diffraction data collection and processing

Diffraction data were collected on Advanced Light Source (ALS) beamline 8.2.2 with an ADSC Quantum 315 CCD detector. The exception was the iodide-soaked crystal diffraction data, which were collected using an R-AXIS IV++ detector in combination with a Rigaku FR-D rotating-anode generator generating Cu Kα radiation. Selected data-collection statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. X-ray diffraction data were processed with DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). SHELXD found five iodide sites and two caesium sites using the single-wavelength anomalous signals from two separate data sets (Sheldrick, 2008 ▶). Despite the larger number of sites and higher phasing power from the iodide data set, phase calculation could not be completed without merging the caesium data set. The programs MLPHARE and DM from the CCP4 suite were used for phase calculations and modification (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶). An electron-density map was generated using the program FOURIER, also from the CCP4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4, 1994 ▶). The automatic tracing program ARP/wARP built over 75% of the chain of the initial model (Perrakis et al., 1999 ▶). The finished model of the apo form of MaModA was used as the starting model for the citrate-bound apo structure. The molybdate-bound MaModA structures were solved by molecular replacement using the EPMR program (Kissinger et al., 1999 ▶). The search model for molecular replacement was created by independently superimposing the two lobes of the apo MaModA model on the molybdate-bound E. coli ModA structure (PDB code 1amf) using MAPS (Zhang et al., 2003 ▶) and then merging the transformed lobes into a single model.

The apo and MoO4 2−-bound MaModA models were built using O (Jones et al., 1991 ▶) and Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▶) and refined with REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶). Refinement statistics are given in Table 1 ▶. The correctness of the final structures was verified by submitting them to the NIH–MBI SAVS validation server (http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/SAVS/) for analysis with the programs ERRAT (Colovos & Yeates, 1993 ▶), PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993 ▶) and WHAT_CHECK (Vriend & Sander, 1993 ▶). Figures were prepared with PyMOL (DeLano, 2002 ▶). Structural homology searches were performed with DALI. The least-squares superposition was calculated using MAPS (Zhang et al., 2003 ▶). Coordinates and molecular structure factors have been deposited in the PDB under the accession codes 3k6u (open conformation, 1.95 Å resolution), 3k6v (open conformation, 1.69 Å resolution), 3k6w (closed conformation, 2.45 Å resolution) and 3k6x (closed conformation, 2.25 Å resolution, two ModA molecules per asymmetric unit).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall structure of M. acetivorans ModA

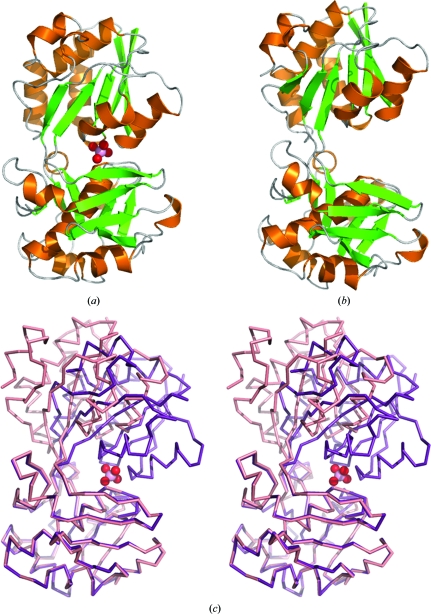

In this study, both the apo and molybdate ligand-bound structures of MaModA were determined. In both conformations the main chain is well ordered and there is clear density for amino acids 41–352; the mature processed ModA is predicted to contain amino acids 25–352, with amino acids 26–40 of MaModA being disordered in both the apo and ligand-bound structures (Fig. 1 ▶). In crystal form II of the ligand-bound conformation there is additional density for ten amino acids from the N-terminal affinity tag. Our MaModA ligand-bound structures have the same overall fold as the previously determined ModA structures that have been described in detail (Hu et al., 1997 ▶; Lawson et al., 1998 ▶; Hollenstein et al., 2007 ▶, 2009 ▶; Quiocho & Ledvina, 1996 ▶). With the exception of the tungstate-bound MaModA structure, the MaModA structure (Fig. 1 ▶) is most similar to the structure of AfModA, with which MaModA shares 58% sequence homology (discussed below).

Figure 1.

Comparison of apo and molybdate-bound MaModA. (a) Ribbon diagram of the molybdate-bound conformation of MaModA (PDB code 3k6w). β-Strands are shown in green, α-helices in orange and loops in gray. The molybdate ligand is shown in space-filling representation with the O atoms colored red and the molybdenum in pink. (b) Ribbon diagram of the apo conformation of MaModA (PDB code 3k6u) colored as in (a). (c) Superposition of the ligand-bound and apo conformations of the MaModA backbone shown in stereo stick representation. The ligand-bound conformation is colored purple and the apo conformation is in salmon. The molybdate is colored as in (a).

MaModA has a mixed α/β bilobal structure in which the two lobes of the protein are separated by a deep cleft. Both the N- and C-termini of the protein are located in one lobe of the protein as the polypeptide chain passes from the first lobe into the second and returns to the first, thus creating two flexible amino-acid ‘hinge’ segments that connect the lobes. In contrast to the bacterial ModA structures, MaModA, like other archaeal ModA proteins (Hollenstein et al., 2009 ▶), contains an additional four-stranded β-sheet element (strands S7, S8, S12 and S13) attached to the second lobe of the protein (Fig. 2 ▶). The function of this additional structural element is unclear as it is not located in a position to affect substrate binding or the interaction of ModA with its cognate ABC transporter. In crystal form II of the ligand-bound protein there are two ModA molecules in the asymmetric unit (ASU). The two molecules in the ASU interact with each other through the four-stranded β-sheet subdomain, with the two subdomains forming an eight-stranded β-barrel that has parallel strands at the seams of the barrel (Fig. 2 ▶). In crystal form I of the ligand-bound structure there is a single MaModA molecule in the ASU that contacts a molecule in the adjacent asymmetric unit by again forming a β-barrel structure. This interaction is not observed in the crystal-packing arrangements for the archaeal ModA structures of Hollenstein and coworkers, as truncations of their expression constructs to enhance protein stability appear to have favored alternate lattice contacts. Since MaModA was determined to be a monomer in solution by size-exclusion chromatography, we believe that dimeric MaModA is the result of crystal packing.

Figure 2.

The β-barrel formed by the four-stranded β-sheet appendage. Two views are shown of the two ligand-bound MaModA molecules found in the asymmetric unit of crystal form II. The β-strands that contribute to the β-barrel are shown in ribbon representation, while the remaining main-chain residues are shown in stick representation.

3.2. The apo MaModA structure and ligand-induced domain reorientation

The previously solved structures of ModA orthologues only represent ligand-bound forms of the protein. Since we solved the apo MaModA structure at 1.95 Å resolution and subsequently determined a higher resolution structure at 1.69 Å from an isomorphous crystal grown from the same crystallization conditions, several points are now evident. Both apo structures contain a single MaModA molecule in the asymmetric unit with unambiguous electron density for amino-acid residues 41–352 (Fig. 1 ▶ b). The two structures are virtually identical and superimpose well upon each other, with an r.m.s.d. of 0.1 Å over 312 Cα atoms. The higher resolution structure has a citrate molecule from the crystallization buffer nonspecifically bound to Ser50 and Ser78 of the ligand-binding site. The side chains of these amino acids have the same orientation in both structures; thus, the geometry of the active site is unperturbed.

The apo MaModA structure, together with the ligand-bound ModA structures, provides crystallographic evidence for the conformational change that has been demonstrated to accompany ligand binding in bacterial ModA proteins (Rech et al., 1996 ▶). Substrate-binding proteins undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding that vary between subtle repositioning of amino-acid residues in the substrate-binding pocket to large rigid-body domain rearrangements involving hinge bending or shear motion (Gerstein et al., 1994 ▶; Brylinski & Skolnick, 2008 ▶). Based on the conformational change that accompanies ligand binding, periplasmic binding proteins (PBPs) have been grouped into two classes: those that bind ligand by hinge bending, such as maltose-binding protein (Sharff et al., 1992 ▶) and sulfate-binding protein (Pflugrath & Quiocho, 1988 ▶), and those in which more modest interdomain conformational changes accompany ligand binding, such as BtuF (Karpowich et al., 2003 ▶) and FhuD (Clarke et al., 2000 ▶). The presence of a hinge region between the two lobes allows members of the former class of PBPs to alternate between open and substrate-bound closed states. Our apo and ligand-bound structures of MaModA reveal the large domain reorientation that MaModA undergoes as a result of the ligand-binding event (Fig. 1 ▶). Comparison of the apo and ligand-bound structures reveals that a hinge region is formed by two amino-acid segments (residues 120–122 and 289–292) that are free of defined secondary structure. Superposition of the first lobe of the apo and ligand-bound structures reveals that one lobe of MaModA, like many of the other periplasmic binding proteins, undergoes a twisting rotation (≃39.4°) about the hinge region, rotating towards the other lobe (this study). As a result, the ligand is bound by amino acids from both the first (Gly49, Ser50 and Ser78) and second lobe (Asp161, Ala163, Glu227 and Tyr245) of the protein (Fig. 3 ▶).

Figure 3.

Superposition stereoview of the ligand-binding sites of the molybdate-bound MaModA structure (PDB code 3k6x) and the tungstate-bound MaModA structure (PDB code 3cfx). (a) Molybdate-bound MaModA is shown in ribbon representation and is colored gray, with the molybdenum colored cyan. The tungstate-bound MaModA is shown in pale green as is the tungstate ligand. Residues that interact with the ligands are shown in stick representation and bonds between the molybdate-bound structure and its ligand are shown by dashed lines. (b) Two-dimensional representation of the octahedral coordination of the molybdate substrate by MaModA.

In addition to the protein–ligand interactions, the ligand-bound structure is stabilized by bonds formed between the two lobes of the protein as a result of the conformational change that accompanies ligand binding. In the apo structure there are three hydrogen bonds between the two lobes of the protein. In the ligand-bound structure one of these bonds is broken and 12 new hydrogen bonds are formed between the two lobes of the protein. The majority of these inter-lobe hydrogen bonds cover the top of the ligand-binding site, thus trapping the ligand deep in the substrate-binding cleft. Additional hydrogen bonds are found on either side of the ligand-binding site, as are two salt bridges that are formed between the two lobes of the protein. One salt bridge is between Arg83 NH2 of the first lobe and Asp160 OD1 of the second lobe, while the second is between Arg120 NH2 of the first lobe and Ile292 O of the second lobe. In the apo structure approximately 460 Å2 of each lobe, an average of 6.6% of the accessible surface area of each lobe, is buried in the interdomain interface, while in the ligand-bound structure 845 Å2 of each subunit, an average of 12% of the accessible surface area of each lobe, is buried in the interdomain interface. As a result of the change in protein conformation, a network of bonds between the two lobes of the protein and between the protein and ligand effectively sequesters the ligand from the surrounding aqueous environment.

The large conformational change demonstrated by our apo and ligand-bound states of MaModA suggests that molybdate transport by the ModB2C2A complex follows the model proposed for ABC transporter-mediated substrate translocation across membranes (Davidson et al., 2008 ▶). In this model the ligand-induced conformational change in ModA alters the proximity of features on the surface of ModA, allowing it to bind to the membrane-spanning ModB subunits of the ABC transporter, the configuration that is seen in the ModB2C2A complex (Hollenstein et al., 2007 ▶). Binding of the liganded ModA to ModB propagates a signal across the membrane that stimulates ATP hydrolysis by the ModC motor domains, which results in the opening of a cavity on the periplasmic face of ModB and the transfer of the substrate from ModA to this cavity. The substrate completes its transit across the membrane as the transporter returns to its resting state. As the transport cycle is completed the now substrate-free ModA protein is released from the transporter and is free to acquire molybdate to reinitiate the transport cycle.

3.3. Ligand-bound MaModA and geometry of the ligand-binding site

Our initial experiments to obtain a molybdate-bound MaModA structure using a tenfold molar excess of molybdate to protein were unsuccessful. This was unexpected as studies with ModA from E. coli have shown that ModA has high affinity for molybdate and tungstate, with K d values of approximately 5 µM (Rech et al., 1996 ▶). Furthermore, the recent tungstate-bound MaModA structure determined by Hollenstein and coworkers used a fourfold to sixfold molar excess of tungstate to MaModA for cocrystallization. However, the inability to obtain molybdate-bound MaModA crystals with a tenfold molar excess of molybdate was confirmed by gel-shift assays, which demonstrated that our MaModA expression construct does not bind molybdate at lower concentrations (data not shown). To determine the appropriate cocrystallization conditions we used differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). The DSF experiments (data not shown) also yielded unexpected results as the melting temperature of MaModA was increased by as much as 33.5 K in the presence of 1.5 M sodium molybdate. A final concentration of 250 mM sodium molybdate, approximately a 500-fold molar excess of substrate to protein, was chosen for cocrystallization trials and molybdate-bound crystals were successfully obtained.

In this study, we obtained two crystal forms of molybdate-bound MaModA. Both crystal forms belonged to space group C2 but crystal form I, which diffracted to 2.45 Å resolution, contains one molecule in the asymmetric unit, while crystal form II, which diffracted to 2.25 Å resolution, contains two molecules per asymmetric unit. The molybdate-bound MaModA structures from the two crystal forms are essentially identical, with the two molecules from crystal form II superimposing well on each other as well as on the single molecule from crystal form I, with least-squares superposition of the three molecules giving r.m.s.d. values of less than 0.3 Å. Likewise, the tungstate-bound MaModA structure (Hollenstein et al., 2009 ▶) is virtually identical to our molybdate-bound MaModA structure (superposition of chain A of molybdate-bound MaModA, PDB code 3k6x, with chain A of tungstate-bound MaModA, PDB code 3cfx, gives an r.m.s.d. of 0.5 Å for the alignment of 292 residues).

Why we required high concentrations of molybdate to obtain molybdate-bound MaModA crystals is puzzling as MaModA was successfully cocrystallized using a fourfold to sixfold molar excess of tungstate and AfModA was cocrystallized with a twofold to threefold molar excess of sodium molybdate. Three possibilities may address this issue: (i) the N-terminal truncation of MaModA has altered the substrate-binding properties of the protein, (ii) tungstate, not molybdate, is the actual substrate of the protein encoded by MA0280 and (iii) the interactions of MaModA with the ModBC transporter may result in subtle changes in the MaModA structure that increase the affinity of MaModA for its metal substrate. The tungstate-bound MaModA structure of Hollenstein and coworkers (PDB code 3cfx) and our molybdate-bound MaModA structures are very similar, with a high degree of conservation in the overall tertiary structure and in the geometry of the ligand-binding site (Fig. 3 ▶). That there is no major difference in overall tertiary structure implies that ligand binding is unaffected and would rule out the first scenario. The second possibility has to be considered owing to the low affinity of MaModA (MA0282) for molybdate that we have seen in vitro. There are two additional proteins (MA2280 and MA1237) in the M. acetivorans genome that have been annotated as molybdate-binding proteins. Both of these proteins are located in operons that encode genes that have been annotated as ABC transporters involved in molybdate uptake. A sequence alignment of ModA homologues that have solved structures with the two additional M. acetivorans ModA proteins reveals that three residues (Ser50, Ser78 and Tyr245 in MA0280 numbering) that interact with the molybdate ligand via their side chains are conserved (Fig. 4 ▶). Examination of the other residues that would be involved in ligand binding suggests that these proteins are more closely related to the E. coli ModA homologue. Structural and biochemical studies to determine the physiological ligand of each of these proteins are in progress. Interestingly, the sequence alignment of ModA proteins (Fig. 4 ▶) reveals that the additional M. acetivorans ModA proteins (MA2280 and MA1237) lack the four-stranded β-sheet appendage (composed of β-strands S7, S8, S12 and S13 in MaModA) that is seen in all of the archaeal ModA structures. The third possibility, that interactions between ModBC and ModA might specify the affinity for molybdate binding by ModA, is also possible. For some bacterial solute transporters the substrate-binding protein is known to associate with the transporter while in the unliganded form (Prossnitz et al., 1988 ▶; Austermuhle et al., 2004 ▶). MaModA could potentially fall into this scheme and interactions with MaModB may modulate MaModA activity. Interestingly, the structure of the MaModBC ABC transporter has revealed the presence of a 120-amino-acid regulatory domain at the C-terminus of the MaModC nucleotide-binding domain (Gerber et al., 2008 ▶). Binding of two molybdate or tungstate molecules, one at each interface of the two MaModC subunits, locks the transporter into a configuration that prevents ATP hydrolysis and therefore inhibits the transport cycle. Altered molybdate binding by MaModA as a result of trans-inhibition of the MaModBC transporter could be a means of molybdate-transport regulation in M. acetivorans. Under this scenario, a low cellular molybdate concentration would result in the transporter stimulating molybdate binding by ModA by modulating its affinity for molybdate. High cellular levels of molybdate would result in trans-inhibition of the transporter, which could then exert an effect on MaModA that decreases its molybdate-binding capacity.

Figure 4.

Sequence alignment of MaModA, E. coli ModA and archaeal ModA homologues for which structures have been determined. Two additional proteins from M. acetivorans (MA1237 and MA2280) that have been annotated as ModA proteins but whose structures have not yet been determined are included. Secondary-structure elements for molybdate-bound MaModA (MA0280, PDB codes 3k6w and 3k6x, this study) are shown above the alignment. Amino-acid residues that have been determined to interact with either molybdate or tungstate ligands from cocrystal structures are indicated as follows: blue, interaction with ligand via backbone amine; red, interaction with ligand via side chain; green, interaction with ligand via both backbone amine and side chain. Identical residues are shaded in dark gray and conserved residues are shaded in light gray. Protein sequences are MA0280, Methanosarcina acetivorans ModA; Archaeoglobus fulgidus ModA, PDB code 2onr; Methanocaldococcus jannaschii ModA, PDB code 3cfz; Pyrococcus horikoshii ModA, PDB code 3cg3; P. furiosus ModA, PDB code 3cg1; E. coli ModA, PDB code 1amf.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have determined the first crystal structure of a molybdate-bound ModA protein from a methanogen (M. acetivorans). The apo and ligand-bound conformations demonstrate the existence of two distinct conformations of the ModA periplasmic binding protein and the conformational change that ModA undergoes in response to ligand binding. The molybdate-bound MaModA conformation retains the octahedral coordination of the metal substrate seen in the tungstate-bound MaModA structure and in other substrate-bound archaeal ModA homologues. The actual physiological ligand of MaModA as well as the role of the other ModA proteins from M. acetivorans remain as yet unresolved.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: ModA, open conformation, 1.95 Å resolution, 3k6u

PDB reference: open conformation, 1.69 Å resolution, 3k6v

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.45 Å resolution, 3k6w

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.25 Å resolution, 3k6x

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of beamline 8.2.2 at the Advanced Light Source for assistance with data collection. We thank the UCLA–DOE Protein Expression Technology Center and UCLA–DOE X-ray Crystallography Core Facility (both supported by Department of Energy Grant DE-FC02-02ER63421) and the UCLA Crystallization Core Facility. We thank Julian Whitelegge at the UCLA Pasarow Mass Spectrometry Laboratory for assistance with LC/MS. We also thank Aled Edwards, Masoud Vedadi, Frank Niesen, Abdellah Allali-Hassani and Patrick Finerty from the Structural Genomics Consortium at the University of Toronto for assistance with the differential scanning fluorimetry experiments. This research was supported by Department of Energy Biosciences Division grant award DE-FG02-08ER64689 (to RPG).

References

- Austermuhle, M. I., Hall, J. A., Klug, C. S. & Davidson, A. L. (2004). J. Biol. Chem.279, 28243–28250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Balan, A., Santacruz-Perez, C., Moutran, A., Ferreira, L. C., Neshich, G. & Barbosa, J. A. (2008). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1784, 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brylinski, M. & Skolnick, J. (2008). Proteins, 70, 363–377. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Clarke, T. E., Ku, S. Y., Dougan, D. R., Vogel, H. J. & Tari, L. W. (2000). Nature Struct. Biol.7, 287–291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 760–763.

- Colovos, C. & Yeates, T. O. (1993). Protein Sci.2, 1511–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Davidson, A. L., Dassa, E., Orelle, C. & Chen, J. (2008). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev.72, 317–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W. L. (2002). PyMOL Molecular Viewer. http://www.pymol.org.

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Galagan, J. E. et al. (2002). Genome Res.12, 532–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gerber, S., Comellas-Bigler, M., Goetz, B. A. & Locher, K. P. (2008). Science, 321, 246–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gerstein, M., Lesk, A. M. & Chothia, C. (1994). Biochemistry, 33, 6739–6749. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gribaldo, S. & Brochier-Armanet, C. (2006). Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci.361, 1007–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hollenstein, K., Comellas-Bigler, M., Bevers, L. E., Feiters, M. C., Meyer-Klaucke, W., Hagedoorn, P. L. & Locher, K. P. (2009). J. Biol. Inorg. Chem.14, 663–672. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hollenstein, K., Frei, D. C. & Locher, K. P. (2007). Nature (London), 446, 213–216. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y., Rech, S., Gunsalus, R. P. & Rees, D. C. (1997). Nature Struct. Biol.4, 703–707. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones, T. A., Zou, J.-Y., Cowan, S. W. & Kjeldgaard, M. (1991). Acta Cryst. A47, 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Karpowich, N. K., Huang, H. H., Smith, P. C. & Hunt, J. F. (2003). J. Biol. Chem.278, 8429–8434. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kissinger, C. R., Gehlhaar, D. K. & Fogel, D. B. (1999). Acta Cryst. D55, 484–491. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Laskowski, R. A., MacArthur, M. W., Moss, D. S. & Thornton, J. M. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst.26, 283–291.

- Lawson, D. M., Williams, C. E., Mitchenall, L. A. & Pau, R. N. (1998). Structure, 6, 1529–1539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Maupin-Furlow, J. A., Rosentel, J. K., Lee, J. H., Deppenmeier, U., Gunsalus, R. P. & Shanmugam, K. T. (1995). J. Bacteriol.177, 4851–4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oelgeschlager, E. & Rother, M. (2008). Arch. Microbiol.190, 257–269. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perrakis, A., Morris, R. & Lamzin, V. S. (1999). Nature Struct. Biol.6, 458–463. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pflugrath, J. W. & Quiocho, F. A. (1988). J. Mol. Biol.200, 163–180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pinotsis, N., Petoukhov, M., Lange, S., Svergun, D., Zou, P., Gautel, M. & Wilmanns, M. (2006). J. Struct. Biol.155, 239–250. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Prossnitz, E., Nikaido, K., Ulbrich, S. J. & Ames, G. F. (1988). J. Biol. Chem.263, 17917–17920. [PubMed]

- Quiocho, F. A. & Ledvina, P. S. (1996). Mol. Microbiol.20, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rech, S., Wolin, C. & Gunsalus, R. P. (1996). J. Biol. Chem.271, 2557–2562. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scholten, J. C. & Stams, A. J. (2000). Microb. Ecol.40, 292–299. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sharff, A. J., Rodseth, L. E., Spurlino, J. C. & Quiocho, F. A. (1992). Biochemistry, 31, 10657–10663. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sowers, K. R., Baron, S. F. & Ferry, J. G. (1984). Appl. Environ. Microbiol.47, 971–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vedadi, M. et al. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 15835–15840.

- Vriend, G. & Sander, C. (1993). J. Appl. Cryst.26, 47–60.

- Zhang, Z., Lindstam, M., Unge, J., Peterson, C. & Lu, G. (2003). J. Mol. Biol.332, 127–142. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zinder, S. H. (1993). Methanogenesis: Ecology, Physiology, Biochemistry and Genetics, edited by J. G. Ferry, pp. 128–206. New York: Chapman & Hall.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: ModA, open conformation, 1.95 Å resolution, 3k6u

PDB reference: open conformation, 1.69 Å resolution, 3k6v

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.45 Å resolution, 3k6w

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.25 Å resolution, 3k6x

PDB reference: ModA, open conformation, 1.95 Å resolution, 3k6u

PDB reference: open conformation, 1.69 Å resolution, 3k6v

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.45 Å resolution, 3k6w

PDB reference: closed conformation, 2.25 Å resolution, 3k6x