The structure of nitric oxide-treated bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) in the fully reduced state was determined at 50 K under light illumination.

Keywords: cytochrome c oxidase, NO-bound, CuB

Abstract

The X-ray crystallographic structure of nitric oxide-treated bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) in the fully reduced state has been determined at 50 K under light illumination. In this structure, nitric oxide (NO) is bound to the CcO oxygen-reduction site, which consists of haem and a Cu atom (the haem a 3–CuB site). Electron density for the NO molecule was observed close to CuB. The refined structure indicates that NO is bound to CuB in a side-on manner.

1. Introduction

Cytochrome c oxidase (CcO) is the terminal oxidase of the respiratory chain and resides in the mitochondrial inner membrane or the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane (Ferguson-Miller & Babcock, 1996 ▶). CcO contains four redox-active metal sites: haem a, haem a 3, CuA and CuB. The haem a 3–CuB site in the transmembrane region catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to two water molecules. Substrate O2 is transferred to the haem a 3–CuB site through a hydrophobic channel in the transmembrane region. The electrons are transmitted from cytochrome c on the positive-side (exterior) surface of CcO through the CuA site and haem a. The protons are taken up from the negative-side (interior) region and are transferred through specific hydrogen-bond networks in the transmembrane region. In addition to the protons for water production, protons are transferred through CcO across the membrane, generating the proton electrochemical gradient.

Nitric oxide (NO), which is an excellent probe for the O2-reduction site, inhibits the catalytic activity of CcO (Cooper & Brown, 2008 ▶; Brunori et al., 2006 ▶). Previous spectroscopic studies have reported that NO binds to the haem a 3–CuB site in the reduced state (Brudvig et al., 1980 ▶; Rousseau et al., 1988 ▶). NO can be photodissociated from the haem a 3 iron (Fea3) and rebinds to Fea3 in a temperature-dependent manner (Yoshida et al., 1980 ▶; LoBrutto et al., 1984 ▶). The rebinding rate of NO to Fea3 2+ is negligibly slow at temperatures below 60 K.

In previous studies, we have determined the atomic structure of the haem a 3–CuB site of bovine heart CcO in both oxidized and reduced states and in complex with inhibitors (Yoshikawa et al., 1998 ▶; Tsukihara et al., 2003 ▶; Aoyama et al., 2009 ▶). Of the four redox-active metal sites of CcO, the function of CuB is the least well understood, since no reliable spectroscopy is available for structural and functional studies of the CuB site. By analogy to the photodissociated CO derivative of CcO (Fiamingo et al., 1982 ▶), binding of NO to CuB under light illumination is most likely. However, formation of the CuB–NO complex has not been demonstrated experimentally. In order to probe the CuB site with NO, we examined the X-ray structure of the NO adduct of bovine heart CcO under light illumination. Here, we report the NO-bound structure of bovine heart CcO in the fully reduced state at 50 K under light illumination.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of crystals of the complex of bovine heart CcO with NO

CcO in the fully oxidized state was purified from bovine heart mitochondria and crystallized as described previously (Tsukihara et al., 1995 ▶). The oxidized crystals were stabilized at 277 K in 40 mM MES–Tris buffer pH 5.8 containing 0.2%(w/v) n-decyl β-d-maltoside and 1%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 4000 (Sigma). The CcO crystals were reduced with 5 mM sodium dithionite supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 1 µM glucose oxidase and 0.5 µM catalase as described previously (Tsukihara et al., 2003 ▶). The NO-bound reduced enzyme was prepared by the addition of 5 mM sodium nitrite (Yonetani et al., 1972 ▶; Brudvig et al., 1980 ▶). Binding of NO to the fully reduced crystal was confirmed by measurement of the α-band absorption using a microspectrometer as described previously (Aoyama et al., 2009 ▶). For the X-ray diffraction measurements, the crystals were frozen in a cryo-helium stream at 50 K in the presence of 45% ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant and illuminated with a halogen lamp.

2.2. X-ray structure determination

X-ray diffraction intensity data were collected at a wavelength of 0.9 Å on BL44XU at SPring-8, Hyogo, Japan. Data processing and scaling were carried out using DENZO and SCALEPACK (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). The structure amplitudes (F o) were calculated using the CCP4 program TRUNCATE (French & Wilson, 1978 ▶). The initial phases to 4 Å resolution were obtained by the molecular-replacement (MR) method using the previously determined structure of the fully oxidized protein (Shinzawa-Itoh et al., 2007 ▶; PDB code 2dyr) as a model. Phase extension to 2.0 Å resolution was carried out by density modification in conjunction with noncrystallographic symmetry averaging using the CCP4 program DM (Cowtan, 1994 ▶). The resultant phase angles (αMR/DM) were used to calculate the electron-density map (MR/DM map) with Fourier coefficients F oexp(iαMR/DM).

The atomic coordinates of fully reduced CcO (Muramoto et al., 2007 ▶; PDB code 2eij) were used to build an initial model in the MR/DM map. Structural refinement was carried out using the program X-PLOR (Brünger et al., 1987 ▶) and the CCP4 program REFMAC5 (Murshudov et al., 1997 ▶). Bulk-solvent correction, anisotropic scaling of the observed and calculated structure amplitudes and TLS parameters were incorporated into the refinement calculation. The individual anisotropic B factor was refined for all the Fe and Cu atoms. During the refinement, the N—O bond length was fixed at 1.15 Å, but the Fea3—N, Fea3—O, CuB—N and CuB—O distances and the Fea3—N—O, O—N—CuB and N—O—CuB angles were not geometrically restrained. The progress of the refinement was assessed by a decrease in the R and R free values (Brünger, 1992 ▶) calculated at each step of the refinement. The correct geometry of the refined structure of NO was confirmed by visual inspection of the electron density observed in (F o − F c)exp(iαc) difference Fourier electron-density maps, where F c and αc are the structure amplitudes and phase angles, respectively, calculated from the refined model excluding NO.

3. Results and discussion

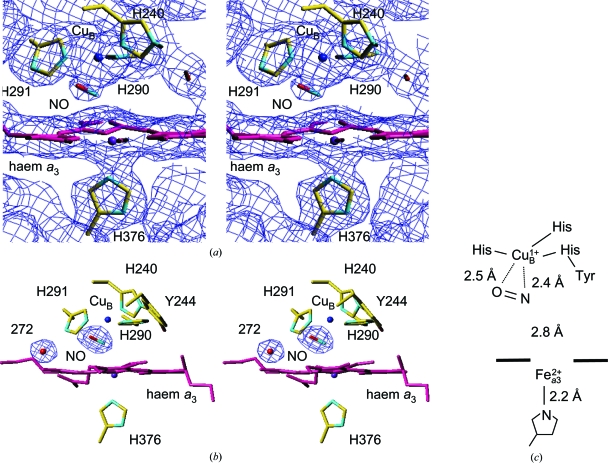

3.1. Structure of the NO-bound CuB in bovine CcO

The X-ray diffraction data set for fully reduced CcO complexed with NO was collected at 50 K under light illumination. Statistics for the data set at 2.0 Å resolution are summarized in Table 1 ▶. The MR/DM electron-density map calculated as described in §2 clearly revealed electron density around the haem a 3–CuB site (Fig. 1 ▶ a). The electron-density hump between CuB and Fea3 is assignable as the NO molecule because no electron density is observed in the fully reduced CcO structure (Yoshikawa et al., 1998 ▶). The electron density of NO is close to CuB, which indicates that NO interacts with CuB rather than with Fea3.

Table 1. X-ray diffraction data and refinement statistics for NO-bound reduced CcO at 50 K under light illumination.

| Diffraction data | |

| σ cutoff | −3 |

| Resolution (Å) | 75.6–2.00 (2.02–2.00) |

| Observed reflections | 1946933 (61603) |

| Independent reflections | 444573 (14713) |

| Averaged redundancy† | 4.4 (4.2) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉‡ | 18.6 (1.57) |

| Completeness§ (%) | 98.9 (99.2) |

| Rmerge¶ (%) | 10.4 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 40.0–2.00 (2.03–2.00) |

| R†† (%) | 18.3 (28.0) |

| Rfree‡‡ (%) | 21.9 (34.0) |

| R.m.s.d.§§ bonds (Å) | 0.032 |

| R.m.s.d.§§ angles (°) | 2.7 |

Redundancy is the number of observed reflections for each independent reflection.

〈I/σ(I)〉 is the average of the intensity signal-to-noise ratio.

Completeness is the percentage of independent reflections observed.

R

merge =

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity value of the ith measurement of hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the corresponding mean value of Ii(hkl) for all i measurements. The summation is over reflections with I/σ(I) larger than −3.

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity value of the ith measurement of hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the corresponding mean value of Ii(hkl) for all i measurements. The summation is over reflections with I/σ(I) larger than −3.

R is the conventional crystallographic R factor, R =

, where F

obs and F

calc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

, where F

obs and F

calc are the observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

R free is the free R factor in the program X-PLOR (Brünger, 1992 ▶) evaluated for 5% of the reflections that were excluded from the refinement.

Root-mean-square deviation.

Figure 1.

(a) Stereoview of the MR/DM electron-density map of the NO-bound reduced haem a 3–CuB sites. The electron density (blue cages) is contoured at the 1.2σ level. (b) Stereoview of the refined structure of the NO-bound reduced haem a 3–CuB sites. The (F o − F c) electron density (blue cages), in which NO and one water (wat272) were omitted from the F c calculation, is contoured at the 5.8σ level. C, N and O atoms in the model structure are shown in yellow, blue and red, respectively. The figures were drawn using the program TURBO-FRODO (Jones, 1978 ▶). (c) Schematic representation of the haem a 3–CuB site. The distance between Fea3 and CuB is 4.9 Å.

The NO molecule was incorporated into the electron density and refinement was continued. The Fea3—NO and CuB—NO bond distances were not restrained in the course of the refinement. The refined structure showed that the Fea3—N distance (2.8 Å) was significantly longer than the CuB—N (2.4 Å) and CuB—O (2.5 Å) distances (Figs. 1 ▶ b and 1 ▶ c) and that NO bound to CuB in a side-on binding mode without coordination to Fea3. An alternative refinement was performed to confirm the side-on binding. An initial structure of NO bound to CuB in an end-on mode was converted to the side-on binding to CuB by the refinement. The refined temperature factors of the N and O atoms in NO and Fea3 and CuB were 32, 36, 27 and 29 Å2, respectively, indicating that temperature factor of NO is slightly higher than those of the surrounding molecules or that the occupancy of NO is not full. Since an alternative structure in which the two atoms of NO are mutually exchanged cannot be excluded in the present crystal structure determination, the assignment of the N and O atoms is arbitrary.

Based on spectroscopic data from previous studies, NO is bound to the reduced Fea3 in the haem a 3–CuB site (Brudvig et al., 1980 ▶; Rousseau et al., 1988 ▶). The treatment of CcO crystals with dithionite and nitrite in this study must provide an Fea3 site that is saturated with NO, as confirmed by absorption spectroscopic analysis of the crystal. Previous reports (Yoshida et al., 1980 ▶; LoBrutto et al., 1984 ▶) strongly suggested that under the present conditions (illumination with a halogen lamp at 50 K) NO is photodissociated from Fea3 and rebinding to Fea3 is negligible. Therefore, the observed geometry of NO in this study indicates that the photodissociated form of NO stabilizes the nearby CuB in a side-on binding. It should be noted that no direct experimental evidence has been reported for NO binding to CuB. Three histidine imidazoles serve as the CuB ligands. Therefore, NO is stabilized at the fourth coordination position of CuB, where no ligand is located in the fully reduced state of CcO, although the space is wide enough for binding of a diatomic ligand (Figs. 1 ▶ b and 1 ▶ c). This structure, together with the geometry of NO at CuB 1+ showing a weak side-on binding, strongly suggests that CuB controls O2 supply to Fea3 2+ by reversibly trapping O2 without forming the peroxide intermediate.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase, 3abk

References

- Aoyama, H., Muramoto, K., Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Hirata, K., Yamashita, E., Tsukihara, T., Ogura, T. & Yoshikawa, S. (2009). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 2165–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brudvig, G. W., Stevens, T. H. & Chan, S. I. (1980). Biochemistry, 19, 5275–5285. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A. T. (1992). Nature (London), 355, 472. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brünger, A., Kuriyan, J. & Karplus, M. (1987). Science, 235, 458–460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brunori, M., Forte, E., Arese, M., Mastronicola, D., Giuffrè, A. & Sarti, P. (2006). Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1757, 1144–1154. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C. E. & Brown, G. C. (2008). J. Bioenerg. Biomembr.40, 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cowtan, K. (1994). Jnt CCP4/ESF–EACBM Newsl. Protein Crystallogr.31, 34–38.

- Ferguson-Miller, S. & Babcock, G. T. (1996). Chem. Rev.96, 2889–2907. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fiamingo, F. G., Altshuld, R. A., Moh, P. P. & Alben, J. O. (1982). J. Biol. Chem.257, 1639–1650. [PubMed]

- French, S. & Wilson, K. (1978). Acta Cryst. A34, 517–525.

- Jones, T. A. (1978). J. Appl. Cryst.11, 268–272.

- LoBrutto, R., Wei, Y.-H., Yoshida, S., Van Camp, H. L., Scholes, C. P. & King, T. E. (1984). Biophys. J.45, 473–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Muramoto, K., Hirata, K., Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Yoko-o, S., Yamashita, E., Aoyama, H., Tsukihara, T. & Yoshikawa, S. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 7881–7886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997). Acta Cryst. D53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol.276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rousseau, D. L., Singh, S., Ching, Y. & Sassaroli, M. (1988). J. Biol. Chem.263, 5681–5685. [PubMed]

- Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Aoyama, H., Muramoto, K., Terada, H., Kurauchi, T., Tadehara, Y., Yamasaki, A., Sugimura, T., Kurono, S., Tsujimoto, K., Mizushima, T., Yamashita, E., Tsukihara, T. & Yoshikawa, S. (2007). EMBO J.26, 1713–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tsukihara, T., Aoyama, H., Yamashita, E., Tomizaki, T., Yamaguchi, H., Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Nakashima, R., Yaono, R. & Yoshikawa, S. (1995). Science, 269, 1069–1074. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tsukihara, T., Shimokata, K., Katayama, Y., Shimada, S., Muramoto, K., Aoyama, H., Mochizuki, M., Shinzawa-Itoh, K., Yamashita, E., Yao, M., Ishimura, Y. & Yoshikawa, S. (2003). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 15304–15309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yonetani, T., Yamamoto, H., Erman, J. E., Leigh, J. S. & Reed, G. H. (1972). J. Biol. Chem.247, 2447–2455. [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S., Hori, H. & Orii, Y. (1980). J. Biochem.88, 1623–1627. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, S., Itoh-Shinzawa, K., Nakashima, R., Yaono, R., Yamashita, E., Inoue, N., Yao, M., Fei, M. J., Libeu, C. P., Mizushima, T., Yamaguchi, H., Tomizaki, T. & Tsukihara, T. (1998). Science, 280, 1723–1729. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase, 3abk

PDB reference: bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase, 3abk