Abstract

Previous single studies have found inconsistent results on sex differences in positive schizotypy, women scoring mainly higher than men, whereas in negative schizotypy studies have often found that men score higher than women. However, information on the overall effect is unknown. In this study, meta-analytic methods were used to estimate sex differences in Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales developed to measure schizotypal traits and psychosis proneness. We also studied the effect of the sample characteristics on possible differences. Studies on healthy populations were extensively collected; the required minimum sample size was 50. According to the results, men scored higher on the scales of negative schizotypy, ie, in the Physical Anhedonia Scale (n = 23 studies, effect size, Cohen d = 0.59, z test P < .001) and Social Anhedonia Scale (n = 14, d = 0.44, P < .001). Differences were virtually nonexistent in the measurements of the positive schizotypy, ie, the Magical Ideation Scale (n = 29, d = −0.01, P = .74) and Perceptual Aberration Scale (n = 22, d = −0.08, P = .05). The sex difference was larger in studies with nonstudent and older samples on the Perceptual Aberration Scale (d = −0.19 vs d = −0.03, P < .05). This study was the first one to pool studies on sex differences in these scales. The gender differences in social anhedonia both in nonclinical samples and in schizophrenia may relate to a broader aspect of social and interpersonal deficits. The results should be taken into account in studies using these instruments.

Keywords: anhedonia, magical thinking, prodrome, schizophrenia, schizotypal personality

Introduction

Many studies have found differences in psychological characteristics between men and women.1 On the other hand, Hyde2 argued on the basis of her meta-analysis using a large range of various psychometric measurements that men and women are in fact similar on most, but not all, psychological variables. Several studies and even some meta-analyses have been published on sex differences in cognition, communication, and social factors, for example.2 There have not been any meta-analyses on sex differences in schizotypy.

In schizophrenia, previous studies on sex differences have found, eg, that men have earlier age of onset, poorer course, and lower family morbid risk of schizophrenia.3,4 There have also been studies related to sex differences in symptomatology. Most studies, eg, Hambrecht et al,5 have reported that men with schizophrenia have more negative symptoms although some studies have reported that there are no differences,6 and one study even found that women have more severe negative symptoms than men.7 Studies have found that women have more affective symptoms, whereas studies on positive symptoms indicate no major sex differences.3,4 Gur et al8 have studied sex differences in symptoms by age; they found that sex differences are evident across the life span. These studies on sex differences in schizophrenia have been reviewed, eg, by Salem and Kring3 and Leung and Chue.4

Construct of Psychosis Continuum and Schizotypy

There are different views regarding the term “schizotypy.” Some, mainly American, researchers use the term to refer to persons with underlying latent liability for schizophrenia but who have not expressed the illness. These persons have a latent personality with genetic vulnerability for schizophrenia, but they may never decompensate into clinical psychosis.9 There is evidence that psychotic symptoms are expressed on a continuum from mild, clinically irrelevant forms to manifestly psychotic symptoms.10 Schizotypy is also suggested, mainly by European researchers, to be expressed on a continuum ranging from psychological well-being to schizophrenia-spectrum personality disorders and to schizophrenia.11,12

Also a multidimensional model of schizotypy has been proposed, with proposed dimensions such as positive schizotypy, negative schizotypy, cognitive disorganization, paranoia, and nonconformity.12 Of these, positive and negative schizotypy are the most consistently replicated dimensions. The positive symptoms of schizophrenia include symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions. In schizotypy, the psychotic-like or “positive” symptoms include, eg, perceptual and magical thinking distortions. Examples of negative symptoms of schizophrenia include, eg, flat affect and social withdrawal, whereas schizotypal patients with negative symptoms are often characterized by, eg, constricted affect and social isolation.13 Men are suggested to score higher in negative schizotypy and women in positive schizotypy; similar sex differences have been found in schizophrenic symptomatology, especially in negative symptoms. Concepts of schizotypy and it's relation to schizophrenia has been reviewed, eg, by Raine.14

Schizotypal personality disorder (SPD) can be seen as one form of schizotypy. According to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, SPD is a “lifelong, pervasive, and enduring disorder with an onset by early adulthood and a stable course”; however, it is also suggested to refer to attenuated form of schizophrenia that may also represent a premorbid stage of this disorder.14 SPD can be approached in 2 ways. Clinically and categorically, it can be assessed by utilizing psychiatric diagnostic criteria, eg, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition).15 Dimensionally it can be measured by utilizing so-called “psychosis proneness” scales, eg, the Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ)16 or the Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales.17–19

Measurements of Schizotypy

Several instruments have been developed to identify subjects at risk for psychotic illness, especially schizophrenia and related psychoses.20 These schizotypy or psychosis proneness scales can be used to identify, eg, vulnerable but symptom-free relatives of schizophrenia patients. Among the oldest and most frequently used schizotypy scales are the Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales developed by Chapman and colleagues. The scales include true-false items for diverse symptoms of the psychosis-prone. The scales are mainly based on the theory of schizotypal traits developed by Meehl.9 His model emphasizes a genetically influenced aberration in neural transmission that could eventuate in different clinical schizophrenia, nonpsychotic schizotypic states, or apparent normalcy depending on the coexistence of other factors.21,22 An important assumption in Meehl's model is that schizotypy can manifest itself behaviorally and psychologically in various degrees of clinical compensation.9,21,22

The Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales include the Magical Ideation Scale (MIS), Perceptual Aberration Scale (PER), Physical Anhedonia Scale (PAS), and Social Anhedonia Scale (SAS). MIS and PER are considered to measure so-called positive and PAS and SAS so-called negative schizotypy. This categorization has been used, eg, recently by Miller and Burns23 in a study on gender differences in schizotypy. MIS measures magical ideation, which is defined as belief in forms of causation that by conventional standards are invalid.19 PER measures distorted perceptions of one's own body and other objects.18 High scorers on PAS have decreased ability to experience physical and sensory pleasures,17 while high scorers on SAS have schizoid lack of interest in social interaction.17 Sample items in these scales are such as “At times I perform certain little rituals to ward off negative influences” (MIS), “Parts of my body occasionally seem dead or unreal” (PER), “I have seldom enjoyed any kind of sexual experience” (PAS), and “People sometimes think that I am shy when I really just want to be left alone” (SAS).

There are no extensive reviews or meta-analyses on sex differences in schizotypal traits, eg, on the Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales. Previous single studies have found inconsistent results on sex differences in magical ideation. Higher scores in men have been reported, eg, by Chmielewski et al,24 and higher scores in women, eg, by Eckblad and Chapman.19 Similarly, in perceptual aberration some studies have found higher scores among men25 and some among women.26 In the positive schizotypy subscales of the SPQ, women have scored higher than men.27 In negative schizotypy, previous single studies have found that men score higher than women,24 but information on the overall effect and on how, eg, age relates to sex differences is unknown.

The Present Study

In this study, using a meta-analytic approach, we pooled previously published studies on Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales presenting mean values by sex in nonclinical samples. The aim was to get estimates for sex differences in these scales and to study the effects of age and student status of the sample on possible sex differences. We hypothesized that men would have more negative and women somewhat more positive schizotypal symptoms. We also expected that in samples with younger mean age or comprising only students, men could have relatively more schizotypal symptoms because men have on average younger age at onset of psychotic illness than women.3,4

Methods

Design

Studies on Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales in healthy adult population were systematically searched from the Medline (Pubmed and Ovid), PsycINFO, SCOPUS, and ISI (Science and Social Science Citation Index) databases in November 2007. The main search used the keywords “physical anhedonia” OR “social anhedonia” OR “perceptual aberration” OR “magical ideation” OR “Chapman scales.” This search resulted in 519 journal articles. Articles were also searched from Google Scholar and from the reference lists of the included articles. We also contacted over 80 authors who have used these scales and asked for possible unpublished data. We included studies using the by far most commonly used versions of the scales, the 30-item MIS, the 35-item PER, the 61-item revised PAS, and the 40-item revised SAS.

Other inclusion criteria were the following. A minimum total sample size of 50 was required, including no fewer than 15 subjects in each sex. Only samples from nonpsychiatric populations (including student samples) were included. In the case of articles with possible overlapping samples, the study with a larger or more informative sample was included. We required information on mean scores and standard deviations (SDs) for the scales by sex.

Location of the study (ie, country and state, if United States, where the data were collected) and available information on the age of the participants (mean or median, SD, and range) were also collected. The data of all the included articles were independently checked by the 2 authors.

Original Studies Presenting Sex Differences

Forty-four studies with samples from 12 countries were included in the final study. Many of the articles used several Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales. Table 1 presents the instruments used, reference, location of the study, sample size (by sex), description of the study population, and information on age of the subjects for the included studies. The included samples often represented unselected populations, although many of the studies included only students (see table 1).

Table 1.

Studies of Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales Included in the Meta-analysis

| Reference | Year | Scales | Location | Sample Size (Men/Women) | Population | Age of the Sample (y) Mean ± SD [range] |

| Atbasoglu et al28 | 2003 | MIS | Turkey | 332 (181/151) | Medical students | 19.9 ± 1.3 [17–28] |

| Bailer et al29 | 2004 | SAS | Germany | 83 (35/48) | Students and employees | 33.5 ± 8.2 |

| Balogh and Merritt30 | 1990 | MIS | Indiana | 3249 (1247/2002) | Undergraduate students | — |

| Barnett and Corballis31 | 2002 | MIS | New Zealand | 250 (70/180) | Undergraduate psychology students | 23.8 [18–59] |

| Berry et al32 | 2006a | SAS | United Kingdom | 230 (58/158)b | Students | Md = 21 [17–67] |

| Camisa et al33 | 2005a | MIS, PER, SAS | Indiana | 54 (35/19) | Colunteers | 34.5 ± 12.1 |

| Chapman et al26 | 1980 | PAS, PER | Wisconsin | 2576 (1209/1367) | College students | — |

| Chapman and Chapman | Unpublished | MIS, SAS | Wisconsin | 1615 (775/840) | College students | — |

| Chen and Su34 | 2006a | PER | Taiwan | 905 (446/459) | Junior high school students | 14.0 ± 0.9 |

| Chen et al35 | 1997a | PER | Taiwan | 115 (52/63) | Junior high school students | 14.0 ± 0.8 |

| Chen et al35 | 1997a | PER | Taiwan | 345 (165/180) | Community | 41.3 ± 12.9 |

| Chmielewski et al24 | 1995 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Illinois | 7691 (3648/4043) | College students | Md = 18 |

| Diduca and Joseph36 | 1997 | MIS | United Kingdom | 201 (87/114) | 45% University students, others employees | 31.3 ± 12.3 [17–71] |

| Dumas et al37 | 1999 | MIS | France | 134 (60/74) | Students | 20.1 ± 1.5 |

| Dumas et al38 | 2000 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | France | 233 (108/225) | Undergraduate students | 21.2 ± 1.5 |

| Etain et al39 | 2007a | PAS | France | 170 (98/72) | Blood donors | 42.7 ± 9.7 [19–64] |

| Farias et al40 | 2005 | MIS | United Kingdom | 99 (43/56) | 54% Students, others volunteers | 38.2 ± 21.1 [17–79] |

| Franken et al41 | 2007a | PAS | The Netherlands | 219 (37/182) | Undergraduate psychology students | 20.0 ± 2.2 [17–28] |

| Glatt et al42 | 2006a | MIS, PAS, PER | Maryland | 55 (24/31) | Volunteers | 17.6 ± 3.7 |

| Graves and Weinstein43 | 2004a | MIS, PAS, PER | Canada | 108 (36/72) | Volunteers, mostly students | 25.5 ± 9.4 [18–72] |

| Jaspers-Fayer and Peters44 | 2005 | MIS | Canada | 413 (156/257) | General population | 19.2 |

| Kelley | Unpublished | MIS | Maryland | 740 (302/438) | Undergraduate students | — |

| Kosmadakis et al45 | 1995 | PAS, SAS | France | 126 (53/73) | General population | 34.2 ± 10.1 [18–70] |

| Kwapil et al46 | In press | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | North Carolina | 6137 (1473/4664) | undergraduate students | 19.4 ± 3.7 y |

| Lenzenweger and Moldin47 | 1990 | PER | New York | 707 (325/382) | First year university students | “Nearly all over 18” |

| Leventhal et al48 | 2006a | PAS | Texas | 151 (46/105) | College students | 22.8 ± 5.3 [18–60] |

| Lipp et al49 | 1994 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Australia | 537 (166/371) | Undergraduate students | — [17–51] |

| Loas50 | 1995 | PAS | France | 384 (154/230) | General population | 31.8 ± 12.2 [17–76] |

| Mathews and Barch51 | 2006a | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Missouri | 389 (160/229)d | Undergraduate students | 19.5 ± 1.2 [18–26] |

| Meyer and Hautzinger52 | 1999 | MIS, PAS, PER | Germany | 279 (111/159) | Community | 23.3 ± 2.6 |

| Miettunen et al | Unpublished | PAS, PER, SAS | Finland | 4908 (2193/2715)d | General population | 30.9 ± 0.3 |

| Miller and Burns23 | 1995 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Georgia | 1106 (404/702) | Undergraduate students | 19.0 ± 2.0 [17–43] |

| Mohr and Leonards53 | 2005 | MIS, PAS | United Kingdom | 122 (20/102) | University students | 20.1 ± 3.5 [18–39] |

| Muntaner et al54 | 1988 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Spain | 735 (355/380) | First year university students | 19.2 ± 2.5 |

| Muris and Merckelbach55 | 2003a | MIS, PER | The Netherlands | 77 (34/43) | undergraduate students | 21.0±1.9 [18-27] |

| Nicholls et al56 | 2005 | MIS | Australia | 933 (212/721) | Undergraduate psychology students | Mode = 20 [17–56] |

| Overby57 | 1993 | MIS, PAS, PER | Texas | 2092 (920/1172) | Undergraduate students | — |

| Peeters | Unpublished | PAS | Canada | 199 (99/100) | University, volunteers | — [18–24] |

| Peltier and Walsh58 | 1990 | MIS, PAS, PER | Montana | 228 (89/139) | College students | — |

| Peeters et al59 | 1999 | MIS | United Kingdom | 267 (81/133)b | Open university students | 36.5 (10.2) [19–75]e |

| Ross et al60 | 2002 | MIS, PAS, PER, SAS | Canada | 473 (142/321) | Undergraduate college students | 20.1 ± 3.4 |

| Scherbarth-Roschmann and Hautzinger61 | 1991 | PAS, PER | Germany | 871 (428/418)b | Healthy volunteers, students, and employees | 22.5 ± 3.76 |

| Tobacyk and Wilkinson62 | 1990 | MIS | Ar-Lo-Mis-Tx | 282 (145/137) | College students | 19.7 ± 2.2 |

| White et al63 | 1995 | MIS | United Kingdom | 183 (78/105) | Normal volunteers | 34.2 ± 11.6 [18–70] |

Note: MIS = Magical Ideation Scale, PER = Perceptual Aberration Scale, PAS = Physical Anhedonia Scale, SAS = Social Anhedonia Scale; Md = median.

Also unpublished data from the authors.

All participants did not report sex.

Unpublished study, data presented in Kwapil et al.25

Maximum sample size, sample sizes vary by scale.

Age for total sample, including also subjects who fulfilled only other scales, in addition, not all participants reported their age. Ar-Lo-Mis-Tx = Arkansas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Texas.

Some studies did not give all the required information, which is why some compromises were required. Barnett and Corballis31 and Ross et al60 did not report SDs by sex, so the SDs from the total sample were used for both sexes. Jaspers-Fayer and Peters44 used a 4-point scale in MIS; however, they dichotomized the scale to 0/1 in the analyses to be comparable with previous studies, and these results are also used in the present study. Chmielewski et al24 and Kwapil et al46 reported results by ethnic groups; in this study, these groups were pooled. Balogh and Merritt30 reported normative data for MIS from 2 Indiana universities; these were pooled to one sample. If median or mode age was given instead of mean that was used in meta-regression. Nine of the samples did not report average statistics for age; these were excluded when studying the effect of age but were included when comparing the samples including only students to the other samples.

Many of the studies included have reported psychometric data on these scales. The main findings of validity studies have been that the internal consistency of the scales is good. Vollema and van den Bosch20 reviewed the Cronbach α values of the scales by the mid-1990s; α values were between .84 and .94 for PER, .82 and .87 for MIS, .71 and .93 for PAS, and 0.76 and 0.88 for SAS. The predictive validity for psychosis has been best for a combination of the MIS and PER, but also promising for the SAS scale.64

Statistical Methods

Effect sizes (ESs) for sex differences are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using forest plots.65 ES is calculated by dividing the difference between mean scores of men and women by the pooled SD. Cohen d values were used as measure for ES. Cohen66 describes a d value of 0.2 as being a small, 0.5 a medium, and 0.8 a large effect. In this study, negative values of d mean that women scored higher on a dimension, and positive values of d indicate that men scored higher. We studied the heterogeneity of the studies by the Q and I2 statistics (with 95% CI). Values of I2 range from 0% to 100%, reflecting the proportion of the total variation across studies beyond chance. A value of 25% describes low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity.67

Due to the possible heterogeneity based on the CIs of I2, the studies were pooled using the more conservative random effects method in all the scales. Meta-regression with a z test65 was used to study the reasons for heterogeneity by exploring the effect of mean age of the sample as a continuous variable. We also studied whether samples including only students differed from other samples, which included mainly older participants. Meta-regression models were done both separately and simultaneously for these 2 variables. Estimated pooled mean values (with SDs) of the scales are presented by sex. We also made an influence analysis in which the meta-analysis estimates are computed omitting one study at a time.65 An α level of .05 was used for all statistical tests. The data were analyzed with Stata 9.0.68

Results

The included samples had a total of 41 003 participants (40% men). The studies were possible heterogeneous in sex differences in PER (I2 = 31%, 95% CI = 0%–59%, Q = 30.65, P = .08) but not in the other scales (I2 = 0%, 95% CI = 0%–41%, Q = 18.66, P = .91, in MIS; I2 = 0%, 95% CI = 0%–45%, Q = 14.79, P = .87, in PAS; I2 = 0%, 95% CI = 0%–55%, Q = 5.38, P = .97, in SAS).

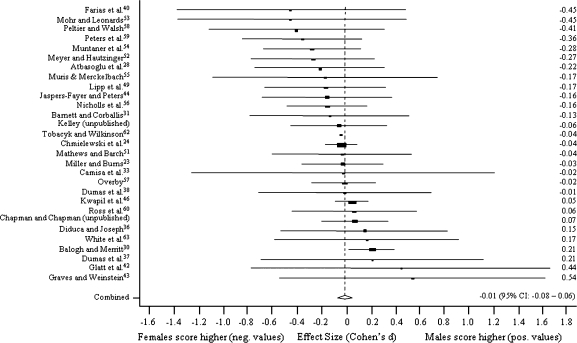

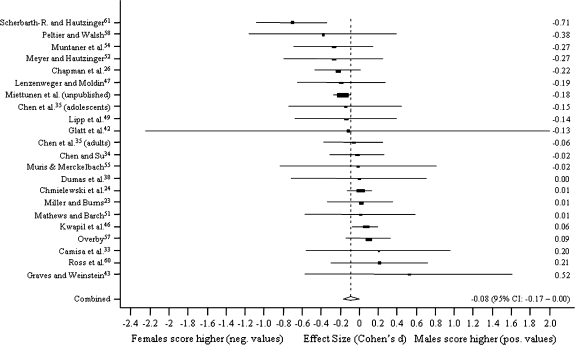

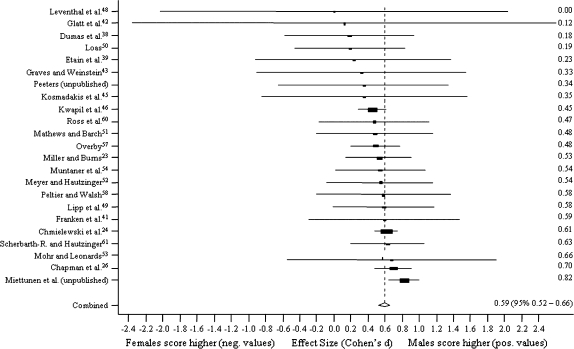

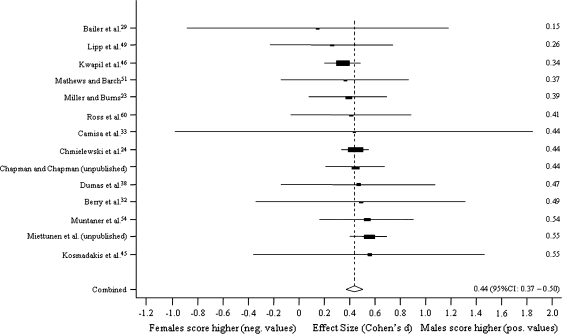

Figure 1 presents random method ESs for differences between men and women in MIS. The results are presented using ESs in forest plots with 95% CIs for the studies. The scores are sorted by the ES, and the pooled ES with 95% CI is also reported. The corresponding forest plots for PER, PAS, and SAS are presented in figures 2–4, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Sex Differences in Magical Ideation Scale.

Fig. 2.

Sex Differences in Perceptual Aberration Scale.

Fig. 3.

Sex Differences in Physical Anhedonia Scale.

Fig. 4.

Sex Differences in Social Anhedonia Scale.

Sex differences were virtually nonexistent in MIS (n = 29, pooled ES, Cohen d = −0.01, z test = −0.33, P = .74) and PER (n = 22, d = −0.08, z = −1.96, P = .05). Men scored higher on PAS (n = 23, d = 0.59, z = 15.91, P < .001) and SAS (n = 14, d = 0.44, z = 13.10, P < .001). In the influence study, ESs were not affected statistically significantly when one study was excluded at a time.

The mean age of the samples was not statistically significantly associated with ESs of sex differences when included as only predictor in the model. However, when sample selection (students vs others) was controlled for, in samples with a higher mean age ESs were higher in PER (z = 2.18, P = .03), ie, women scored relatively higher with increasing mean age of the sample. Furthermore, in samples which included also other subjects besides students, sex difference was larger in PER (d = −0.21 vs d = −0.01, z = 3.19, P = .001), also when adjusted for the sample mean age. Table 2 summarizes mean values by sex in all studies and dividing the samples to students only and to other samples.

Table 2.

Summary of the Sex Differences and Pooled Mean Scores in Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales, in Total and Comparing Studies With Only Students and Other Studies

| Magical Ideation Scale | Perceptual Aberration Scale | Physical Anhedonia Scale | Social Anhedonia Scale | |||||||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| N | Mean | Mean | ES (d) | N | Mean | Mean | ES (d) | N | Mean | Mean | ES (d) | N | Mean | Mean | ES (d) | |

| All studies | 29 | 8.29 | 8.54 | −0.01 | 22 | 5.25 | 5.67 | −0.08 | 23 | 14.72 | 11.73 | 0.59 | 14 | 9.96 | 7.77 | 0.44 |

| Only students | ||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 21 | 8.62 | 9.08 | −0.05 | 15 | 5.72 | 6.11 | −0.03 | 14 | 14.62 | 11.37 | 0.47 | 10 | 9.89 | 7.71 | 0.42 |

| No | 8 | 7.42 | 7.11 | −0.02 | 7 | 4.25 | 4.72 | −0.19a | 9 | 14.86 | 12.27 | 0.40 | 4 | 10.13 | 7.91 | 0.42 |

Note: ES (d) = effect size (Cohen d). Statistically significant (P < .05, z test) ESs are in bold.

When compared with “only students,” ES was statistically significantly smaller in studies that included only students in Perceptual Aberration Scale (z = 3.19, P = .001).

Discussion

This is the first report that pools studies on sex differences in Wisconsin Schizotypy Personality Scales. The main results of this study were that men scored higher on physical and in social anhedonia, with ESs at medium level, 0.59 and 0.44, respectively. We found no sex difference in magical ideation and perceptual aberration; this was the opposite to that of presented in some of the previous reviews relating to positive schizotypy.14

Sex Differences in Magical Ideation and Perceptual Aberration

There were no sex differences in the scales related to positive schizotypy, ie, magical ideation and perceptual aberration. This finding is similar to that found in positive symptoms of schizophrenia.3,4 Some studies have compared mean scores between the sexes in other related schizotypy scales and have reported similar findings. However, previous reviews have also concluded that women tend to score higher in scales of positive schizotypy.14

SPQ is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Third Edition Revised) diagnostic symptoms of SPD.16 In the subscale “odd beliefs or magical thinking” of the SPQ, researchers have reported higher scores for women. For example, in the study by Raine,27 the ES was 0.28 and in the study by Miller and Burns23 0.14. In these studies, sex differences in the “unusual perceptual experiences” subscale were small and inconsistent. These varying results in sex differences in positive schizotypy could also be due to differences in the instruments used. In general, different psychological instruments may differ in the way they contain items that are more appropriate for different sexes; this has been suggested to be the case, eg, in a scale for neuroticism.69 It should be noted that the PER has a more clinical approach to schizotypy than the other schizotypy scales.70 The current study should be replicated using other schizotypy instruments, eg, in SPQ.16

We also found that in perceptual aberration women scored higher than men in nonstudent (mainly older) compared with student samples; however, the ES was still small (0.19). This may be due to chance because only a few studies included older subjects. Mason and Claridge71 studied the “unusual experiences” subscale of the Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE). The subscale correlated negatively with age (r = −0.18). The researchers found that women under 22 scored somewhat higher than did men under 22, men scored slightly higher among those aged 21–30 years, women scored higher in age group 31–50 years, while men scored slightly higher again among the older participants. These results may be due to small sample size or may indicate that the possible effect of age is not straightforward.

Sex Differences in Physical and Social Anhedonia

Berrios and Olivares72 have reviewed the history of the anhedonia concept. Anhedonia is a symptom commonly associated with both schizophrenia and depression. However, Chapman Anhedonia Scales do not measure depressive anhedonia. Anhedonia in schizophrenia has been reviewed recently by Wolf.73While the content validity of the Chapman Anhedonia Scales may be somewhat outdated, they remain the standard anhedonia questionnaires in the field.74

In our meta-analysis, men scored quite consistently higher on the 2 anhedonia scales. On the O-LIFE subscale of introvertive anhedonia, men scored higher in the study by Mason and Claridge,71 although the ES was only 0.11. In the study by Miller and Burns,23 men scored statistically significantly higher on the 2 subscales of SPQ, which relate to negative symptoms of schizophrenia. ESs were 0.33 on the “constricted affect” and 0.34 on the “no close friends” subscale.

John et al75 found in their retrospective study that women with schizophrenia commonly had anhedonic symptoms before the onset of illness, whereas men commonly had disciplinary problems. This could mean that although anhedonia is more common among men, the women having these symptoms could be at relatively higher risk of developing schizophrenia. Due to this, different gender-specific norms in anhedonia should be considered, eg, in high-risk designs.

Studies on sex differences in negative symptoms, such as anhedonia, among individuals with diagnosis of schizophrenia are inconsistent, although most studies have reported more symptoms among men. In schizophrenia, anhedonia is often present already in the premorbid phase.76 In our meta-analysis in healthy subjects, anhedonia increased with the mean age of the samples; there is also evidence for this in the original studies of other schizotypy scales. For example, in the UK study using O-LIFE, the introvertive anhedonia subscale correlated positively with age (r = 0.19).71 Among participants with familial risk for psychosis, Freedman et al77 found higher scores for physical anhedonia among men than women. The sex differences in schizophrenia, eg, in these traits, may reflect proneness to different subtypes of schizophrenia.3

Gender differences in social anhedonia (both in general population and among schizophrenia patients) may also relate to a broader aspect of interpersonal or social deficits rather than to the dichotomy of positive/negative schizotypy.23 The finding of Dworkin78 supports this: they found that male schizophrenia patients had poorer premorbid social competence than female patients, although they found no gender differences in negative symptoms. Primary (and persistent) negative symptoms often begin already at the premorbid level; thus, premorbid anhedonia (eg, measured by PAS and SAS) could be a risk factor especially for the development of schizophrenia with primary negative symptoms.23,76 Horan et al79 studied schizotypy scales and clinical symptoms in 3 assessment points, and they found that physical anhedonia is less sensitive to changes in symptomatology in schizophrenia than magical ideation and perceptual aberration. It has also been found that negative schizotypy (measured with PAS and SAS) is more heritable than positive schizotypy (measured with MIS and PER) (see Horan et al79). This genetic component may interact with psychosocial and environmental factors. The existence of gender differences in negative but not positive schizotypy in our sample supports this finding. In all, as we have found support for our results on studies using other schizotypy scales (O-LIFE and SPQ) indicating that the findings are likely to be independent of the scales used and are probably based on differences in psychopathology between males and females.

Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales and Risk of Schizophrenia

The link between schizotypy (eg, measured by the Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales) and schizophrenia is not straightforward. There are some studies that have found support for usefulness of the Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales in predicting psychotic symptoms and even schizophrenia: However, the sample sizes have been quite small, especially the number of new schizophrenia cases after the follow-up. For 10 years, Kwapil80 followed up subjects who had scored high in SAS (n = 34) and controls (n = 139); at follow-up, 24% of those in high-risk group were diagnosed with schizophrenia-spectrum diagnosis, compared with only 1% of the controls. Gooding et al81 followed up high scorers in SAS (n = 32) and a control group (n = 44) for 5 years; at the end of the follow-up 16% of the high scorers and none in control group had a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. In studies comparing subjects who already have schizophrenia and controls, schizophrenia patients have scored significantly higher in these scales; eg, in the study by Camisa et al32 ESs were large (about 1.5). Catts et al82 have reviewed studies on relatives of schizophrenia patients, and they concluded that relatives tend to score higher than controls in PAS but not in PER. These findings give support for the usefulness of the scales, but the scales could be developed further, eg, the wording of the items is somewhat old fashioned.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

There are limitations in this study design. Possible differences in the original samples may affect the results and conclusions of this meta-analysis because most of the samples included only students, for example. There were only 4–9 nonstudent samples in the different scales. The schizotypy scales are often used to estimate the risk of developing schizophrenia, and student age samples are useful for that. However, also among older subjects, scales of this kind may serve in epidemiological research as instruments to detect an intermediate phenotype or endophenotype, reflecting the genetic liability of an individual to psychotic disorder. In such research, the quantitative scales are hypothesized to be more informative than the dichotomous clinical diagnosis.83 College students differ from other subjects of that age in terms of intellectual ability; but they have been considered generally representative of their cohort in terms of their rates of psychopathology.84 In future, more studies using samples from general population are needed.

There is still controversy regarding the underlying nature of schizotypy, ie, whether it is fully continuous12 or not.9 This article studied scales based on the latter theory, without taking a stand to the nature of schizotypy. In addition, the dimensional structure of schizophrenia is still controversial.85 In most of the previous studies as well as in the current study, the SAS was thought to measure negative schizotypy; however, the recent study by Kwapil et al46 found that it also relates to positive schizotypy.

We used the mean age of the sample to study the association of age to sex difference; this is not the most efficient way to study this. Nevertheless, some associations were found, although there were only few older (nonstudent) samples. It would have been interesting to study differences between different cultures as well, but we were not able to locate any African and only a few Asian samples.

There are notable strengths in this study. This was the first meta-analysis on sex differences in schizotypal symptoms. These symptoms relating to the prodromal phase of psychosis are of increasing interest. Meta-analyses in general are laborious, and in this study, the literature search was particularly extensive, including several database searches and contacts with numerous researchers. All the studies included were read by 2 researchers. In addition, the use of meta-regression is an advantage to most meta-analyses. This enabled us to present the possible effect of age and being a student sample on sex differences in the scales.

Conclusions

This study was the first one to pool studies on sex differences in Wisconsin Schizotypy Scales. The results were quite concordant with the results in schizophrenia and other schizotypal scales. It can be concluded that compared with women, men had more physical and social anhedonia, which relate to negative schizotypy. The gender differences in social anhedonia found here in nonclinical samples, and also in schizophrenia, may relate to a broader aspect of interpersonal and social deficits. There were some sex differences in magical ideation and perceptual aberration in single studies, but when the studies were pooled no sex differences were found. This could mean that there really are no major sex differences in positive schizotypy; however, this should also be studied using meta-analytic methods in other schizotypy instruments. Based on the systematic search of the articles, we can also conclude that more studies using samples from general population are needed. The data provided on the sex differences in schizotypy should be taken into account in future studies, eg by giving norms by sex, and in general on studies on schizotypy and schizophrenia prediction.

Funding

Academy of Finland (120 479 to J.M.).

Acknowledgments

We thank the following researchers, who helped in the search for data: Katherine Berry, Wei J. Chen, Bruno Etain, Ingmar H. A. Franken, Stephen J. Glatt, Roger E. Graves, Martin Hautzinger, Michael P. Kelley, Adam M. Leventhal, Gwenolé Loas, Jennifer R. Mathews, Harald Merckelbach, Thomas D. Meyer, Peter Muris, Brian F. O'Donnell, and Sara Weinstein.

References

- 1.Miettunen J, Veijola J, Lauronen E, Kantojärvi L, Joukamaa M. Sex differences in Cloninger's temperament dimensions—a meta-analysis. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol. 2005;60:581–592. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salem JE, Kring AM. The role of gender differences in the reduction of etiologic heterogeneity in schizophrenia. Clin Psychol Rev. 1998;18:795–819. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung A, Chue P. Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:3–38. doi: 10.1111/j.0065-1591.2000.0ap25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Häfner H. Gender differences in schizophrenia in three cultures: results of the WHO collaborative study on psychiatric disability. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:117–121. doi: 10.1007/BF00788756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Addington D, Addington J, Patten S. Gender and affect in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewine RJ, Meltzer HY. Negative symptoms and platelet monoamine oxidase activity in male schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res. 1984;12:99–109. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(84)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gur RE, Perry RG, Turetsky BI, Gur RC. Schizophrenia throughout life: sex differences in severity and profile of symptoms. Schizophr Res. 1996;21:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(96)00023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meehl PE. Schizotaxia, schizotypy, schizophrenia. Am Psychol. 1962;17:827–838. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verdoux H, van Os J. Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2002;54:59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00352-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gooding DC, Iacono WG. Developmental Psychopathology. New York, NY: USA:Wiley & Sons; 1995. Schizophrenia through the lens of a developmental psychopathology perspective; pp. 535–580. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claridge G, McCreery C, Mason O, et al. The factor structure of ‘schizotypal’ traits: a large replication study. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35:103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1996.tb01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siever LJ. Brain structure/function and the dopamine system in schizotypal personality disorder. In: Raine A, Lencz T, Mednick SA, editors. Schizotypal Personality. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 272–288. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raine A. Schizotypal personality: neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:291–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association. American Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raine A. The SPQ: a scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophr Bull. 1991;17:555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Scales for physical and social anhedonia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85:374–382. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chapman LJ, Chapman JP, Raulin ML. Body-image aberration in schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1978;87:399–407. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.87.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eckblad M, Chapman LJ. Magical ideation as an indicator of schizotypy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:215–225. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vollema MG, van den Bosch RJ. The multidimensionality of schizotypy. Schizophr Res. 1995;21:19–31. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenzenweger MF. Psychometric high-risk paradigm, perceptual aberrations, and schizotypy: an update. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:121–135. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenzenweger MF. Schizotypy: an organizing framework for schizophrenia research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2006;15:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller LS, Burns SA. Gender differences in schizotypic features in a large sample of young adults. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183:657–661. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chmielewski PM, Fernandes LOL, Yee CM, Miller GA. Ethnicity and gender in scales of psychosis proneness and mood disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:464–470. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwapil TR, Crump RA, Pickup DR. Assessment of psychosis proneness in African-American college students. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58:1601–1614. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman LJ, Edell WS, Chapman JP. Physical anhedonia, perceptual aberration and psychosis-proneness. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6:639–653. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raine A. Sex differences in schizotypal personality in a nonclinical population. J Abnorm Psychol. 1992;101:361–364. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.2.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Atbaşoğlu EC, Kalaycioğlu C, Nalçaci E. Büyüsel Düşünce Ölçeği'nin Türkçe formunun üniversite öğrencilerindeki geçerlik ve güvenilirliği [Reliability and validity of Turkish version of Magical Ideation Scale in university students] Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2003;14:31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bailer J, Volz M, Diener C, Rey E-R. Reliability and validity of German versions of the Physical and Social Anhedonia Scales and the Perceptual Aberration Scale. Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 2004;33:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balogh DW, Merritt RD. Accounting for schizophrenics’ Magical Ideation scores: are college-student norms relevant? Psychol Assess. 1990;2:326–328. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnett KJ, Corballis MC. Ambidexterity and magical ideation. Laterality. 2002;7:75–84. doi: 10.1080/13576500143000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berry K, Wearden A, Barrowclough C, Liversidge T. Attachment styles, interpersonal relationships and psychotic phenomena in a non-clinical student sample. Pers Individ Dif. 2006;41:707–718. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Camisa KM, Bockbrader MA, Lysaker P, Rae LL, Brenner CA, O'Donnell BF. Personality traits in schizophrenia and related personality disorders. Psychiatr Res. 2005;133:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen WJ, Su CH. Handedness and schizotypy in non-clinical populations: influence of handedness measures and age on the relationship. Laterality. 2006;11:331–349. doi: 10.1080/13576500600572693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen WJ, Hsiao CK, Lin CCH. Schizotypy in community samples: the three-factor structure and correlation with sustained attention. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:649–654. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.4.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diduca D, Joseph S. Schizotypal traits and dimensions of religiosity. Br J Clin Psychol. 1997;36:635–638. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1997.tb01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dumas O, Saoud M, Gutknecht C, Dalery J, d'Amato T. Traductions et adaptations françaises des questionnaires d'idéation magique (MIS, Eckblad et Chapman, 1983) et d'aberrations perceptives (PAS, Chapman et al., 1978) [Magical Ideation Scale (MIS) and Perceptual Aberration Scale (PAS). Presentation of the French translations and preliminary norms in a sample of French students] Encephale. 1999;25:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dumas P, Bouafia S, Gutknecht C, Saoud M, Dalery J, d'Amato T. Validations des versions françaises des questionnaires d'idéation magique (MIS) et d'aberrations perceptives (PAS) [Validation of French versions of magical ideation and perceptual aberrations questionnaires] Encephale. 2000;26:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Etain B, Roy I, Henry C, et al. No evidence for physical anhedonia as a candidate symptom or an endophenotype in bipolar affective disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farias M, Claridge G, Lalljee M. Personality and cognitive predictors of New Age practices and beliefs. Pers Individ Dif. 2005;39:979–989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franken IHA, Rassin E, Muris P. The assessment of anhedonia in clinical and non-clinical populations: further validation of the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) J Affect Disord. 2007;99:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glatt SJ, Stone WS, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT. Psychopathology, personality traits and social development of young first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:337–345. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.016998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Graves RE, Weinstein S. A Rasch analysis of three of the Wisconsin scales of psychosis proneness: measurement of schizotypy. J Appl Meas. 2004;5:160–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaspers-Fayer F, Peters M. Hand preference, magical thinking and left-right confusion. Laterality. 2005;10:183–191. doi: 10.1080/13576500442000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosmadakis CS, Bungener C, Pierson A, Jouvent R, Widlocher D. Traduction et validation de l'Echelle Révisée d'Anhédonie Sociale (SAS Social Anhedonia Scale, M.L. Eckblad, L.J. Chapman et al., 1982). Étude des validités interne et concourante chez 126 sujects sains [Translation and validation of the Revised Social Anhedonia Scale. Study of the internal and concurrent validity in 126 normal subjects] Encephale. 1995;21:437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwapil TR, Barrantes-Vidal N, Silvia PJ. The dimensional structure of the Wisconsin schizotypy scales: factor identification and construct validity. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:444–457. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lenzenweger MF, Moldin SO. Discerning the latent structure of hypothetical psychosis proneness through admixture analysis. Psychiatry Res. 1990;33:243–257. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leventhal AM, Chasson GS, Tapia E, Miller EK, Pettit JW. Measuring hedonic capacity in depression: a psychometric analysis of three anhedonia scales. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:1545–1558. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipp OV, Arnold SL, Siddle DAT. Psychosis proneness in a nonclinical sample. I: a psychometric study. Pers Individ Dif. 1994;171:395–404. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loas G. L’évaluation de l'anhédonie en psychopathologie. In: Guelfi JD, Gaillac V, Dardennes R, editors. Psychopathologie Quantitative. Paris, France: Masson; 1995. pp. 230–239. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mathews JR, Barch DM. Episodic memory for emotional and non-emotional words in individuals with anhedonia. Psychiatry Res. 2006;143:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer TD, Hautzinger M. Intrafamiliäre Ähnlichkeit von Physischer Anhedonie, Wahrnehmungsabweichungen und Magischem Denken [Intrafamilial resemblance of Physical Anhedonia, Perceptual Aberration and Magical Ideation] Z Klin Psychol Psychother. 1999;28:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohr C, Leonards U. Does contextual information influence positive and negative schizotypy scores in healthy individuals? The answer is maybe. Psychiatry Res. 2005;136:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Muntaner C, Garcia-Sevilla L, Fernandez A, Torrubia R. Personality dimensions, schizotypal and borderline personality traits and psychosis proneness. Pers Individ Dif. 1988;9:257–268. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muris P, Merckelbach H. Thought-action fusion and schizotypy in undergraduate students. Br J Clin Psychol. 2003;42:211–216. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicholls MER, Orr CA, Lindell AK. Magical ideation and its relation to lateral preference. Laterality. 2005;10:503–515. doi: 10.1080/13576500442000265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Overby LA. Handedness patterns of psychosis-prone college students. Pers Individ Dif. 1993;15:261–265. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peltier BD, Walsh JA. An investigation of response bias in the Chapman Scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1990;50:803–815. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peters ER, Joseph SA, Garety PA. Measurement of delusional ideation in the normal population: introducing the PDI (Peters et al. Delusions Inventory) Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:553–576. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ross SR, Lutz CJ, Bailley SE. Positive and negative symptoms of schizotypy and the five-factor model: a domain and facet level analysis. J Pers Assess. 2002;79:53–72. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7901_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scherbarth-Roschmann P, Hautzinger M. Zur psychometrischen erfassung von schizotypy. Methodische überprüfung und erste validierung von zwei skalen zur erfassung von risikomerkmalen [Psychometric detection of schizotypy. Validation of a German version of the Physical Anhedonia scale and the Perceptual Aberration scale] Z Klin Psychol. 1991;20:238–250. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tobacyk JJ, Wilkinson LV. Magical thinking and paranormal beliefs. J Soc Behav Pers. 1990;5:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- 63.White J, Joseph S, Neil A. Religiosity, psychoticism, and schizotypal traits. Pers Individ Dif. 1995;19:847–851. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwapil TR, Chapman LJ, Chapman J. Validity and usefulness of the Wisconsin Manual for Assessing Psychotic-like Experiences. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:363–375. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sterne JAC, Bradburn MJ, Egger D. Meta-analysis in stata. In: Egger M, Davey Smith G, Altman D, editors. Systematic Reviews in Health Care: Meta-analysis in Context. London, UK: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 347–372. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks J, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stata Corporation. Stata User's Guide, Release 9. College Station, Tex: Stata Press. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jorm AF. Sex differences in neuroticism: a quantitative synthesis of published research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1987;21:501–506. doi: 10.3109/00048678709158917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johns LC, van Os J. The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1125–1141. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mason O, Claridge G. The Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences (O-LIFE): further description and extended norms. Schizophr Res. 2006;82:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.12.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Berrios GE, Olivares JM. The anhedonias: a conceptual history. Hist Psychiatry. 1995;6:453–470. doi: 10.1177/0957154X9500602403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolf DH. Anhedonia in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8:322–328. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Horan WP, Kring AM, Blanchard JJ. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: a review of assessment strategies. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:259–273. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.John RS, Mednick SA, Schulsinger F. Teacher reports as a predictor of schizophrenia and borderline schizophrenia: a Bayesian decision analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 1982;91:399–413. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.91.6.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Möller H-J. Clinical evaluation of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Freedman LR, Rock D, Roberts SA, Cornblatt BA, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. The New York High-Risk Project: attention, anhedonia and social outcome. Schizophr Res. 1998;30:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(97)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dworkin RH. Patterns of sex differences in negative symptoms and social functioning consistent with separate dimensions of schizophrenic psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:347–349. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Horan WP, Reise SP, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, Nuechterlein KH. The validity of Psychosis Proneness Scales as vulnerability indicators in recent-onset schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res. 2008;100:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kwapil TR. Social anhedonia as a predictor of the development of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:558–565. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gooding DC, Tallent KA, Matts CW. Clinical status of at-risk individuals 5 years later: further validation of the psychometric high-risk strategy. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:170–175. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Catts SV, Fox AM, Ward PB, McConaghy N. Schizotypy: phenotypic marker as risk factor. Austr N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:S101–S107. doi: 10.1080/000486700229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bearden CE, Freimer NB. Endophenotypes for psychiatric disorders: ready for primetime? Trends Genet. 2006;22:306–313. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Psychopathology associated with drinking and alcohol use disorders in the college and general adult populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. How many and which are the psychopathological dimensions in schizophrenia? Issues influencing their ascertainment. Schizophr Res. 2001;49:269–285. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(00)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]