Abstract

Purpose: Due to its limited angular scan range, breast tomosynthesis has lower resolution in the depth direction, which may limit its accuracy in quantifying tissue density. This study assesses the quantitative potential of breast tomosynthesis using relatively simple reconstruction and image processing algorithms. This quantitation could allow improved characterization of lesions as well as image processing to present tomosynthesis images with the familiar appearance of mammography by preserving more low-frequency information.

Methods: All studies were based on a Siemens prototype MAMMOMAT Novation TOMO breast tomo system with a 45° total angular span. This investigation was performed using both simulations and empirical measurements. Monte Carlo simulations were conducted using the breast tomosynthesis geometry and tissue-equivalent, uniform, voxelized phantoms with cuboid lesions of varying density embedded within. Empirical studies were then performed using tissue-equivalent plastic phantoms which were imaged on the actual prototype system. The material surrounding the lesions was set to either fat-equivalent or glandular-equivalent plastic. From the simulation experiments, the effects of scatter, lesion depth, and background material density were studied. The empirical experiments studied the effects of lesion depth, background material density, x-ray tube energy, and exposure level. Additionally, the proposed analysis methods were independently evaluated using a commercially available QA breast phantom (CIRS Model 11A). All image reconstruction was performed with a filtered backprojection algorithm. Reconstructed voxel values within each slice were corrected to reduce background nonuniformities.

Results: The resulting lesion voxel values varied linearly with known glandular fraction (correlation coefficient R2>0.90) under all simulated and empirical conditions, including for the independent tests with the QA phantom. Analysis of variance performed on the fit line parameters revealed statistically significant differences between the two different background materials and between 28 kVp and the remaining energies (26, 30, and 32 kVp) for the dense experimental phantom. However, no significant differences arose between different energies for the fatty phantom, nor for any of the many other combinations of parameters.

Conclusions: These strong linear relationships suggest that breast tomosynthesis image voxel values, after being corrected by our outlined methods, are highly positively correlated with true tissue density. This consistent linearity implies that breast tomosynthesis imaging indeed has potential to be quantitative.

Keywords: tomosynthesis, phantoms, digital simulation, tissue composition, cancer, breast imaging

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

In current clinical practice, mammography is the standard imaging modality for breast cancer screening and diagnosis.1 The advantages of mammography include a reasonably high sensitivity, high resolution, and low patient dose. However, a mammogram still suffers from being a two-dimensional projection of a three-dimensional object. The resulting overlap of normal fibroglandular tissue cannot only obscure the detection and characterization of lesions but also present false alarms leading to unnecessary recall studies.2, 3

To address this key limitation of mammography, 3D x-ray imaging techniques have been developed, including dedicated breast computed tomography (CT), which takes cone-beam x-ray projection images of the uncompressed breast in a full 360° scan, thus enabling reconstruction of a 3D breast volume.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Digital x-ray tomosynthesis9, 10 (often abbreviated as “tomo”) for the breast is a form of limited-angle cone-beam CT.11, 12 A restricted number of projection images are acquired in an arc in the conventional mammography projection geometry, while the breast is compressed adjacent to the detector. Although some information is lost due to angular undersampling, breast tomo still creates a 3D volume at a dose comparable to that of traditional mammography. Moreover, the tomo device itself is usually based on an existing full-field digital mammography (FFDM) system. Although compression is required, this ensures proper posterior tissue coverage, immobilization to minimize motion artifacts, and a low dose.13 The similarity of tomo to FFDM in terms of patient positioning, image acquisition, and aspects of image display suggests that there is minimal retraining required for the technologist or radiologist.14 As such, breast tomosynthesis is a 3D breast imaging modality with the potential to replace mammography.

Extracting quantitative information from tomosynthesis images could potentially allow improved characterization of lesions. In addition, it may facilitate clinically acceptable processing of tomosynthesis images, such as with the application of film characteristic curves, such that tomo slice images more closely mimic the appearance of mammography. However, the quantitative ability of breast tomo is potentially limited by several factors when compared to CT. The central-slice theorem dictates that the narrow tube arc limits the amount of spatial information available in the z-direction. The commonly used reconstruction method of filtered backprojection (FBP) also incorporates a ramp filter that reduces lower spatial frequency information.15 These shortcomings were manifested as out-of-plane slice contributions and in-plane ringing artifacts that appear in areas of large density changes throughout the reconstructed volume.

The current study will investigate breast tomo quantification using both Monte Carlo simulations with voxelized phantoms as well as empirical measurements done on a prototype breast tomo system with tissue-equivalent uniform phantoms. This is the first time that such simulated and empirical phantom analyses have been combined exclusively for breast tomo quantification. Finally, we hypothesize that a simple new image processing technique may quantify tissue density in a single slice from reconstructed breast tomo images, and we will assess strengths and limitations of this approach.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was performed using two platforms: Monte Carlo simulations were conducted using voxelized phantoms and breast tomosynthesis geometry,16 and then empirical studies were performed using tissue-equivalent plastic phantoms that were imaged on an actual breast tomosynthesis prototype system.

Breast tomosynthesis geometry

All studies were based on a Siemens prototype MAMMOMAT Novation TOMO breast tomosynthesis system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a W∕Rh anode∕filter and 45° total angular span (Breast tomosynthesis is an investigational practice and is limited by U.S. law to investigational use. It is not commercially available in the U.S. and its future availability cannot be ensured). Twenty-five projection images were taken for each scan, with approximately 2° angular spacing. The pixel pitch of the 24×30 cm2 amorphous selenium detector was 0.085 mm, and no antiscatter grid was used. The source was located 65 cm from the detector and 59 cm from the tube axis of rotation; the anode focal spot was 0.3 mm.

Monte Carlo simulations

The simulations were carried out with PENELOPE Monte Carlo software.17 The geometry used was identical to that used by Saunders et al. to mimic the aforementioned Siemens prototype system.18 The x-ray spectrum used was generated using a DOS-based Spectrum program to simulate 28 kVp beam with a tungsten target filtered with 50 μm rhodium.19 The simulations included added electronic noise, and the voxelized phantom was modeled as a 4.5 cm thick breast equivalent material that contained 11 1×1×0.5 cm cuboid lesions with densities ranging from 0% to 100% glandular fraction at 10% intervals. The lesions were embedded at three different depths within the phantom: 5 mm from the detector cover (lesions near the bottom of the phantom), 20 mm from the detector cover (lesions at the center of the phantom), and 35 mm from the detector cover (lesions near the top of the phantom) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

To-scale schematic of voxelized phantom used in the Monte Carlo simulations. The phantom is 4.5 cm thick with three identical sets of 11 cuboid lesions each. One lesion set was placed at each of three depths within the phantom.

The elemental composition of each lesion was estimated by linearly interpolating between NIST published values for adipose and breast tissue (ICRU-44). The material surrounding the lesions was set to be either fat or glandular equivalent, thus requiring two separate simulation runs of three experimental settings each (Table 1). For each simulation experiment, 25 projection images were generated (one per tomosynthesis angle), keeping primary and scattered photon counts separate to facilitate independent analysis. These simulations were run on a Linux–Intel shared computing cluster at Duke using 25 parallel computing nodes per simulation run (one per projection image) and 8–9 h per node. In total, the two simulation runs involved a computational cost of approximately 400 CPU hr.

Table 1.

Parameters tested in the three simulation experiments: Effects of overlapping material (material density), lesion distance from detector cover (depth in phantom), and scattered radiation.

| Overlapping material | Lesion distance from detector cover (mm) | Radiation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | 5 | 20 | 35 | Primary only | Primary and scattered |

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

| x | x | x | ||||

Empirical measurements

Images were taken of tissue-equivalent plastic phantoms under several configurations. All phantoms comprised of two “background” slabs of 10×15×2 cm3 uniform tissue-equivalent plastic (CIRS Inc., Norfolk, VA). For each phantom image, the background consisted of two slabs of either fat-equivalent plastic or glandular-equivalent plastic. To facilitate comparison against the aforementioned virtual phantoms, eleven lesions varying in density from 0% glandular∕100% adipose to 100% glandular∕0% adipose in increments of 10% glandular manufactured by CIRS (cylindrical 1 cm diameter by 0.5 cm height) were placed in 0.5 cm of Crisco brand vegetable shortening (J.M. Smucker Co., Orrville, OH) to avoid large density changes due to air contrast, resulting in a single thin slab that could be placed at different depths relative to the background slabs (Fig. 2). Ordering of the eleven lesions was randomized to minimize false trend effects due to gradual background changes such as beam hardening or scatter. The experimental settings tested dependence on one parameter at a time, holding all else constant (Table 2). Additionally, the proposed analysis methods were validated using a different, widely available QA phantom. Though the surrounding plastic is still uniform, the phantom contains a 1 cm thick five-part stepwedge, microcalcification specks, nylon fibers, a line pair target, and 75% dense hemispheric masses of varying sizes. For this test, the CIRS Model 11A breast phantom was imaged with a 27 kVp beam and exposure of 180 mA s. The stepwedge inclusions were used to test the ability of the proposed technique to correctly quantify the three largest 75% dense masses.

Figure 2.

Schematic of phantom arrangements used to test for lesion depth dependence. The lesion layer was identical for all images, whereas the background slabs were both either fat-equivalent or glandular-equivalent plastic. To test energy and exposure dependence, the central arrangement was used for all images.

Table 2.

Parameters tested in the empirical experiments: Effects of overlapping material (material density), lesion distance from detector cover (depth in phantom), beam energy, and tube exposure.

| Overlapping material | Lesion distance from detector cover (mm) | Energy (kVp) | Exposure (mA s) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | 0 | 20 | 40 | 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 125 | 150 | 175 | 200 | 225 |

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

Image reconstruction and analysis

All image reconstruction was performed with a FBP algorithm (TOMOENGINE software, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany).20 The reconstruction rendered volumetric data sets with voxels of 0.085×0.085×1 mm3 (i.e., slice thickness of 1 mm). The voxel values were left as floating point numbers rather than rescaled to integer values to avoid loss of precision. Quantitative analysis was performed by measuring the mean and standard deviation for a 5×5 mm region of interest (ROI) in each lesion in one slice per image volume. The slice analyzed was that traversing the center of each lesion set based on the known geometry of the acquisition. The relationship between the mean image intensity value and the known glandular fraction for each lesion could then be investigated and evaluated in terms of linearity by calculating the correlation coefficient R2 for each least-squares line, one per set of imaging parameters. Calculation of R2 follows Eq. 1

| (1) |

where yi is each mean intensity value, is the overall mean of intensity values, xi is each known glandular fraction, and is the overall mean of the known glandular fractions.

To preliminarily assess how materials in each slice affect surrounding slices, we likewise measured the mean and standard deviation for a 4.25×4.25 mm2 ROI with the same center as that previously used for the empirical and simulated 10% and 70% glandular lesions in all slices throughout the entire phantom. Slightly smaller ROIs were used in this portion of the study to minimize artifacts from aliased lesion edges entering the regions measured. The relationship between slice distance from the protective plastic cover resting 1.55 cm above the detector (or depth in the phantom) and voxel value could then be used to assess slice-to-slice continuity and out-of-plane contributions as the lesion comes into and out of focus.

Nonuniform background correction

In order to reduce false background trends due to local nonuniformities that are a result of heel effect, scattered radiation, and tomo reconstruction, a simple in-plane background correction method was applied. For each lesion ROI, an adjacent ROI of identical size was measured in the surrounding material (either Crisco® or simulated tissue-equivalent plastic), and the mean intensity of the background ROI was subtracted from that of the lesion ROI [Eq. 2].

| (2) |

where D(lesion) is the “corrected” lesion voxel value, V(lesion)meas is the lesion ROI voxel value as measured from the image, and V(bkgd)meas is the corresponding ROI mean value for the surrounding material.

Moreover, because the correction method depends on the material surrounding the lesions, and the virtual phantoms contain one of two contrasting background materials (either fat or glandular-equivalent plastic), another normalization was necessary to compare the corrected ROI voxel values. This additional subtraction is equivalent to setting the corrected ROI mean for the 0% glandular lesion to zero despite the surrounding material, as demonstrated in Eq. 3

| (3) |

where D(0%) is the corrected value for the 0% lesion ROI, V(0%)meas is the raw image voxel value measured in a region determined to be “true fat” by the human observer, and V(bkgd0%)meas is the raw measured voxel value of an ROI from material adjacent to the predetermined true fat region. Then, Eq. 4 [in combination with Eq. 3] will complete the conversion to surrounding material-invariant voxels

| (4) |

where D(0%) is determined with Eq. 3, and, as mentioned previously, V(lesion)meas and V(bkgd)meas are the raw values measured from image ROIs, and D(lesion)NoBkgd is the new surrounding material-invariant net intensity value for each lesion. Therefore, by definition

| (5) |

This correction method was applied to all reconstructed images prior to plotting the corrected tomo voxel values against known glandular density.

RESULTS

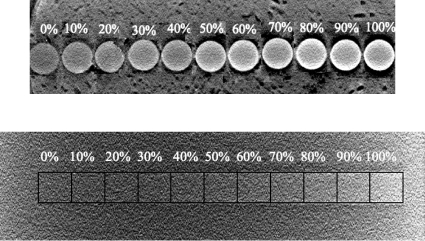

After reconstruction, there was a visible difference in brightness of the lesions: Denser lesions appeared brighter in the images for both the virtual voxelized and the actual tissue-equivalent plastic phantoms (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(Top) One slice through the cylindrical lesions from a reconstructed volume image with the known glandular fraction (in percent) of each plastic piece. For display purposes, the regions of interest were resorted from the actual random order. (Bottom) The same was done for the cuboidal lesions from a Monte Carlo simulation result. Note the change in grayness from left to right in both images (lesion brightness increases with density); however, it is difficult to distinguish between the simulated lesions because lesions are placed directly adjacent to each other in order of increasing density; dark outlines and labels were added later to facilitate lesion distinction.

Simulation results

The efficacy of our background correction method is well-demonstrated in plotting the first simulation results under the “ideal” scenario of scatter-free projection images for the glandular-overlapped phantom; one can clearly see the variation seen in the tomo values from ROIs placed in the background material adjacent to each lesion, especially those near the 0% and 100% lesions due to their placement near the edge of the phantom (Fig. 4). The raw voxel values are negative before correction because of the limited number of projections acquired in tomo; negative contributions from backprojected, filtered projection images would typically cancel out in the case of complete angular sampling. Moreover, due to the ramp filter incorporated in reconstruction, the low frequencies are suppressed which causes the average float value for the image to be near zero, and hence the small, negative raw voxel values.

Figure 4.

Demonstration of local background correction method. Original lesion values (squares) were corrected by subtracting nearby background values (pluses) to produce corrected lesion values (x’s) plotted on the secondary y-axis that vary linearly with lesion glandularity. Least-squares best fit line for corrected (postsubtraction) voxel values is shown R2=0.989. Bars on corrected voxel values represent standard error.

For all reconstructed images, once the ROI values were collected and corrected as governed by Eqs. 2, 4, least-squares analysis was used to determine the relationship between voxel value and known lesion glandular fraction for each imaging scenario (both empirical and simulated). The correlation coefficient R2, as defined previously in Eq. 1, can be considered a figure of merit for the linearity of the relationship between corrected voxel value and known lesion density under each set of imaging parameters. Error bars were not shown in Fig. 4 for the lesion and background means because standard errors were less than 1E-03, such that error bars would have been smaller than the markers themselves.

Simulation experiments 1 and 2: Effects of scattered radiation and background density

Once our background correction was applied, the effects of scattered radiation on linearity can be seen for the lesions centrally embedded in each of the two different overlapping materials in Fig. 5. The following relationships were obtained from least-squares analysis (Table 3):

Figure 5.

Plot of image voxel values for simulations comparing both background material density and the effects of scattered radiation along with trend lines determined by least-squares analysis and standard error bars

Table 3.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for simulation experiments comparing density of overlapping material and inclusion of scattered radiation (lines displayed with data in Fig. 5).

| Overlapping material | Radiation | Least-squares results (line parameters) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | P | P+S | Slope (*10−4) | Y -Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | x | (1.97, 2.24) | (−8.18, 7.28) | 0.993 | ||

| x | x | (1.37, 1.67) | (−13.5, 3.99) | 0.984 | ||

| x | x | (1.91, 2.17) | (−0.0960, 15.0) | 0.993 | ||

| x | x | (1.26, 1.55) | (2.51, 20.2) | 0.981 | ||

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) between the best fit line parameters (i.e., slopes and intercepts) revealed that there is a statistically significant difference between the line slopes and intercepts for images containing both primary and scattered photon counts and the images that only contain the primary signal (p⪡1E-04) for both phantom backgrounds. Comparing the background materials under each condition revealed statistically significant differences in intercepts between fat and glandular backgrounds for images with both primary and scattered signal (p<0.003) but not in slopes (p>0.20). No statistically significant differences were reported between the fit lines for fat and glandular backgrounds in the images reconstructed without scatter (p>0.08 for both slope and intercept).

Simulation experiment 2: Effect of depth

After correction and subsequent least-squares analysis, the relationships and fitness values derived are seen in Table 4, and the corrected voxels values with fit lines are in Fig. 6.

Table 4.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for simulation experiments comparing lesion depth, all include scattered radiation. (Lines are displayed with data in Fig. 6.)

| Overlapping material | Distance from detector cover (mm) | Least-squares results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | 5 | 20 | 35 | Slope (*10−4) | Y -Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | x | (1.37, 1.67) | (−13.5, 3.99) | 0.984 | |||

| x | x | (1.40, 1.72) | (−15.8, 3.08) | 0.982 | |||

| x | x | (1.55, 1.83) | (−13.8, 2.45) | 0.989 | |||

| x | x | (1.43, 1.68) | (5.12, 19.8) | 0.989 | |||

| x | x | (1.52, 1.76) | (−3.76, 10.2) | 0.991 | |||

| x | x | (1.45, 1.67) | (0.985, 14.1) | 0.991 | |||

Figure 6.

Plot of voxel values for different lesion depths for the virtual phantoms with (left) fat background and (right) glandular background with bars showing standard error. Both plots share the same y-axis scale. Legend refers to lesion set location (“bottom” meaning closest to detector).

An ANOVA between the best fit line parameters along with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) test for multiple comparisons of means on the ANOVA results21 revealed that, in the fat background phantom, the fit lines for centrally embedded lesions had a statistically significantly different intercept from that for the lesion set farthest away from the detector (padj=0.047), whereas all slopes can be considered homogeneous (p>0.18). For the glandular background phantom, homogeneous line slopes (p>0.46) and intercepts (p>0.065) were observed.

Empirical results

Empirical experiment 1: Effect of depth

After performing identical operations to the ROI measurements made in the simulation images to the empirical measurements, an ANOVA revealed that there was no significant difference between the least-squares fit lines for any of the three different slice depths tested for each of the overlapping materials tested (all p>0.60). The slope and intercept confidence intervals for the relationship between corrected voxel value and known glandular percentage along with correlation coefficients are seen in Table 5. The fit lines and corrected voxel values are seen in Fig. 7. Standard error bars are not shown in any of the empirical image plots because for all conditions the standard error was less than 2.5E-04, so the bars would be smaller than marker symbols.

Table 5.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for empirical experiments comparing lesion depth (Lines are displayed with data in Fig. 7).

| Overlapping material | Distance from detector cover (mm) | Least-squares results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | 0 | 20 | 40 | Slope (*10−4) | Y -Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | x | (2.46, 3.79) | (−22.1, 56.6) | 0.926 | |||

| x | x | (2.71, 3.67) | (−8.02, 49.0) | 0.961 | |||

| x | x | (2.75, 3.34) | (1.31, 36.3) | 0.984 | |||

| x | x | (2.11, 3.21) | (−58.7, 6.57) | 0.930 | |||

| x | x | (1.95, 3.20) | (−50.1, 24,2) | 0.905 | |||

| x | x | (2.27, 3.06) | (−49.4, −2.79) | 0.963 | |||

Figure 7.

(Left) Plot showing lack of dependence of corrected voxel values on depth for the fat background phantom and (right) likewise for the glandular phantom. Legend refers to relative position of lesion layer to background slabs. Standard error bars not shown as they are smaller than marker symbols.

Empirical experiment 2: Effect of background material

Since there was no significant difference for the different slice depths, only the centrally placed lesion phantoms taken at 28 kVp and 175 mA s were plotted to compare the two different overlapping materials (Fig. 8). As expected from viewing the plot, the fit line intercepts are indeed significantly different for the different background materials (p<4E-05); the line slopes, on the other hand, were not significantly different (p>0.20).

Figure 8.

Plot illustrating the dependence of corrected voxel values on background material density for the empirical phantoms. Standard error bars are not shown, as they are smaller than marker symbols.

Empirical experiment 3: Effect of energy

Testing the different energies while keeping the exposure, overlapping material, and lesion placement constant showed that, for the fat-overlapping phantom (Fig. 9), none of the energies tested have fit lines that are statistically significantly different from each other (from ANOVA, p>0.50 for both slopes and intercepts). The least-squares derived line parameters’ 95% confidence intervals are shown in Table 6 below.

Figure 9.

Plot demonstrating lack of dependence of voxel values on energy for phantom with fat-equivalent plastic as the background material. Standard error bars are not shown, as they are smaller than marker symbols.

Table 6.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for empirical experiments comparing energy for fat background (Lines are displayed with data in Fig. 9).

| Energy (kVp) | Least-squares results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | Slope (*10−4) | Y -Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | (2.69, 3.86) | (−19.1, 50.1) | 0.947 | |||

| x | (2.46, 3.79) | (−22.1, 56.6) | 0.926 | |||

| x | (2.37, 3.50) | (−10.6, 56.6) | 0.938 | |||

| x | (2.20, 3.44) | (−16.4, 57.5) | 0.921 | |||

However, for the glandular-overlapping phantom (Fig. 10), an ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test showed that the fit line intercept value is significantly different at 28 kVp (padj<0.049 for all comparisons of energies with 28 kVp). The remaining energies’ line intercepts are not significantly different from each other (padj>0.80). No statistically significant difference exists between any of the line slopes for all four energies (p>0.50). The best fit line parameter confidence intervals for each energy are seen in Table 7 below, and data values are plotted with the lines in Fig. 10.

Figure 10.

Plot demonstrating the dependence on energy for glandular background phantom imaged at 28 kVp and independence of energy for same phantom imaged at 26, 30, or 32 kVp. Standard error bars are not shown, as they are smaller than marker symbols.

Table 7.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for empirical experiments comparing energy for glandular background (Lines are displayed with data in Fig. 10).

| Energy (kVp) | Least-squares results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 28 | 30 | 32 | Slope (*10−4) | Y -Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | (2.34, 3.57) | (−43.7, 29.4) | 0.929 | |||

| x | (2.11, 3.21) | (−58.7, 6.57) | 0.930 | |||

| x | (2.42, 3.16) | (−24.0, 19.7) | 0.970 | |||

| x | (2.26, 2.87) | (−14.1, 22.3) | 0.975 | |||

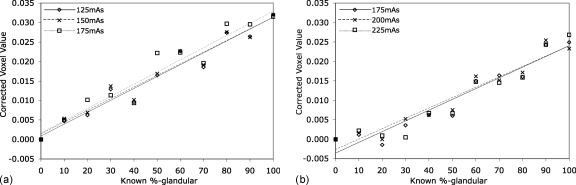

Empirical experiment 4: Effect of exposure

For the different exposures tested, all other parameters including energy, overlapping material, and lesion placement were held constant for comparison. For each different background, no statistically significant difference in fit line parameters was noted between the three exposure levels tested (p>0.50 for both slopes and intercepts). This is especially made apparent in the corrected voxel values plot (Fig. 11). Line parameter confidence intervals are in Table 8.

Figure 11.

Plots showing lack of lack of dependence on exposure level for the corrected image voxel values within each background density (fat left, glandular right). Standard error bars are not shown, as they are smaller than marker symbols

Table 8.

Summary of least-squares analysis results (95% confidence intervals) for empirical experiments comparing exposure (Lines are displayed with data in Fig. 11).

| Overlapping material | Exposure (125–175 mA s fat; 175–225 mA s glandular) | Least-squares results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fat | Glandular | Low | Mid | High | Slope (*10−4) | Y-Intercept (*10−4) | R2 |

| x | x | (2.51, 3.57) | (−23.1, 40.8) | 0.948 | |||

| x | x | (2.45, 3.52) | (−16.8, 46.7) | 0.946 | |||

| x | x | (2.46, 3.79) | (−22.1, 56.6) | 0.926 | |||

| x | x | (2.17, 3.36) | (−71.4, −0.829) | 0.924 | |||

| x | x | (2.11, 3.21) | (−58.7, 6.57) | 0.930 | |||

| x | x | (2.11, 3.42) | (−73.9, 3.63) | 0.910 | |||

Phantom testing

All studies above were based on a single type of phantom (eleven 0.5 cm thick, customized lesions within uniform material) for both empirical and simulation experiments. As a preliminary test of robustness, the background correction rescaling method was applied to a different, commonly available CIRS Model 11A breast phantom. Linearity was well-demonstrated for the five inclusions comprising the stepwedge (Fig. 12) with R2=0.989, and our methods were further tested on three of the 75% dense masses. Densities of these masses were underestimated as shown by the markers appearing below the fitted line, with greater errors observed for smaller masses. The smallest mass would appear to be approximately 55% dense instead of its known density of 75%.

Figure 12.

Plot showing test of methods on CIRS Model 11A breast phantom 1 cm thick stepwedge and three of the seven hemispheric lesions with thicknesses noted on the plot legend.

Investigation of out-of-plane effects

Voxel values were measured in all slices above and below the central slice containing two cylindrical lesions of 10% and 70% glandular composition for empirical and two cuboid lesions of the same densities for simulated phantoms. All five cubic stepwedge lesions were likewise measured in the CIRS Model 11A breast phantom. The lesions were each embedded in a 0% (fat), a 100% (glandular), or a 50% dense surrounding background. The resulting plots are seen in Fig. 13.

Figure 13.

Plots of z-dependence of voxel values in slices above and below the 10% and the 70% lesion for phantoms containing 11 lesions and likewise for all five stepwedge lesions in the CIRS Model 11A phantom. Slices known to include the lesion cross-sections are marked with black bar near the x-axis. Analysis was performed using simulation (top row) and empirical phantoms (bottom rows), and with fat (left column) versus glandular (right column) versus 50% (bottom center) surrounding background.

DISCUSSION

There have been several previous studies in quantitative breast tomo that focus on optimization of dual energy image acquisition and subsequent iodine quantification.18, 22, 23, 24, 25 Other groups have investigated the use of tomo to assess cancer risk in terms of density or texture features.16, 26, 27 In previous studies from our group, before incorporating the in-plane background correction with an improved FBP reconstruction algorithm, the ability of tomo to quantify breast density was found to depend on both the x-ray beam energy and the tube exposure level.28

Specifically, in this study, a wide variety of parameters were evaluated which may affect the quantitative ability of breast tomo. First, Monte Carlo simulation techniques were used to establish feasibility while ensuring control over all parameters. Several effects were studied: Scattered radiation, lesion depth in the phantom, x-ray tube energy, and x-ray beam exposure level. Adding the effects of scattered radiation (Fig. 5) appeared to slightly reduce the goodness of fit in the data and to significantly decrease the slope of the least-squares line (Table 3); one effect of the scattered radiation was thus to reduce the lesion contrast. Second, the empirical measurements showed that the slope and intercept values from the best fit relationship between corrected voxel value and density did not depend on depth (distance from the detector cover), energy, or exposure level for the fat background phantoms. The lack of significant difference between fit line parameters for most energies in each background may be due to loss of low-frequency information from the FBP reconstruction. However, there was a significant difference in the fit line intercept for the glandular background phantom when imaged at 28 kVp as compared to that of other backgrounds or energies. It is unclear why this effect was observed. There was likewise no difference between line parameters for various exposure levels while keeping energy constant for each phantom. Thus, over a wide range of clinical energy and exposure levels, the linear relationship of corrected voxel value to known density depends only on the density of the overlapping material. Therefore, with the exception of a few specific conditions, the reconstructed voxel values were always highly positively correlated with true tissue density, with all least-squares “goodness of fit” R2 values above 0.9.

The proposed technique was equivalent to a subtraction of the background corresponding to fat, thus calibrating many different imaging conditions together into a common, linear framework. This subtraction likely was successful because it served to remove the low-frequency, nonuniform background within each slice due to such factors as heel effect, scatter, and reconstruction.

This study, despite its encouraging results, has several important limitations. We only applied our method to phantoms with uniform material surrounding each area of interest. It remains to be seen how well this technique would perform on anthropomorphic phantoms or, more importantly, on actual breasts which can be highly heterogeneous. Both the CIRS Model 11A phantom test and the z-dependence study revealed that out-of-plane contributions definitely play a role that deserves further study. Testing our background correction method on the 11A phantom yielded encouragingly linear results for the large, cuboid stepwedge inclusions. However, the voxel values for the 75% dense hemispherical masses fell below the fitted stepwedge line, which is likely a result of the contributing signal from the material above and below each slice which may be exacerbated by partial volume effects within the slice of interest. For each mass, as size decreased, there was greater contribution from the surrounding 50% dense material which correspondingly resulted in a lower estimate of the actual glandular density. In future work, it would be interesting to assess more thoroughly the effects of lesion size and shape upon quantitation.

The aforementioned saliency of out-of-plane contributions is likewise exemplified in the z-dependence investigation. As shown in Fig. 13, consistently across all simulations and empirical phantoms, the lesion in-plane contrast to its immediate surroundings appears to have propagated through all slices. This effect is demonstrated by comparing the central two plots in Fig. 13 in which the less dense Crisco® surrounding the lesions created positive lesion-to-background contrast that is carried throughout the volume, regardless of the density of the material surrounding the lesions in the z-direction. This may be attributed to the FBP reconstruction causing a loss of low-frequency information. This counterintuitive result further reinforces the need for a future investigation of alternative reconstruction algorithms (such as simple backprojection and statistical iterative reconstruction), which may provide better low-frequency information in the z-direction. Once the out-of-plane contributions can be fully accounted for in uniform phantoms and then quantified for anthropomorphic phantoms, our technique can perhaps be applied toward in-plane lesion density measurements in more realistic heterogeneous breasts and eventually volumetric risk-assessment measurements such as overall breast density.

The loss of low-frequency information inherent to FBP reconstruction is also manifested in the lack of significant differences for the energies tested, which is contradictory to CT. The trend of decreasing slope with increasing energy is seen very subtly in both fatty and glandular backgrounds, but preservation of more low-frequency information should cause the lines in Figs. 910 to be further spread out as they would be in CT. Furthermore, since we only investigated different x-ray beam energies for the empirical images, it would be interesting to compare those results with Monte Carlo simulations run under equivalent energy-varying conditions (requiring three additional simulations per overlapping material density, equivalent to quadrupling the computational cost).

Another point to consider is that our correction scheme depended on the initial resetting of the true fat voxels to zero. Such operations might be difficult to perform on clinical images (e.g., heterogeneously or uniformly dense breasts). Possible solutions to this issue may include defining true fat based on using an external calibration phantom containing materials with known densities next to the breast, or locating a low-valued region among a slab average over several slices surrounding the slice of interest to be true fat.

It likewise remains to be determined what the effect is for different breast thicknesses on quantitation; all phantoms in this study (virtual and otherwise) were 4.5 cm thick, corresponding to an average breast thickness. After conducting the z-dependence study, we conjecture that out-of-plane contributions might be different for different phantom thicknesses. Thicker phantoms may have less contribution from air contrast above and below the phantom but may also have more out-of-plane degradation, especially with heterogeneous breasts. Given the uncertainties in future clinical AEC settings, it may also be worth investigating a wider range of exposures in the empirical images, especially when different thickness phantoms are tested. As we demonstrated previously that out-of-plane contributions must be more fully investigated under different conditions, it is likely that varying the thickness will change how these unwanted contributions affect quantitation.

CONCLUSIONS

This study assessed the quantitative potential of breast tomosynthesis using a prototype system and a relatively simple reconstruction and image processing algorithm. The Monte Carlo simulation studies and experimental phantom images, including the 11A test phantom, all imply that breast tomosynthesis imaging has potential to be quantitative. In other words, quantitative information can likely be obtained from reconstructed tomosynthesis images. Moreover, the fact that lesion intensity varies linearly with known density for the wide range of conditions imaged in this study implies the basis for image processing steps to translate voxel values to quantitative units (the tomosynthesis equivalent to CT numbers) after the proposed background correction scheme is applied. However, despite the encouraging results, the study possessed several limitations such as testing only uniform phantoms of equal thicknesses and the lack of corrections to alleviate out-of-plane contributions.

A successful approach toward fully quantitative tomosynthesis imaging may have many useful applications. For example, this approach may allow quantitative assessment of lesion density such as to discern solid, fatty, or fluid-containing lesions. It may also allow a more natural, mammogramlike visual display wherein screen brightness corresponds to radiographic density within each slice. Therefore, the quantitative potential of breast tomosynthesis is very encouraging and justifies the need for further investigation to ascertain the limits of the linear dependences determined in this study and to explore effects of other imaging or patient parameters.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH∕NCI Grant No. R01 CA112437, Siemens Healthcare, Cancer Research and Prevention Foundation, Clare Boothe Luce Fellowship Program, and Susan G. Komen for the Cure. Special thanks also go to Craig Beam of the University of Illinois at Chicago for statistical advice, to Thomas Mertelmeier of Siemens Healthcare for providing insightful explanations of tomo FBP reconstruction, and to Martin Tornai of Duke Radiology and Moustafa Zerhouni of CIRS for providing phantom materials.

References

- US Preventive Services Task Force, “Screening for breast cancer: Recommendations and rationale,” Ann. Intern Med. 137, 344–346 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher S. W. and Elmore J. G., “Clinical practice. Mammographic screening for breast cancer,” N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1672–1680 (2003). 10.1056/NEJMcp021804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore J. G., Armstrong K., Lehman C. D., and Fletcher S. W., “Screening for breast cancer,” JAMA, J. Am. Med. Assoc. 293, 1245–1256 (2005). 10.1001/jama.293.10.1245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning R., Conover D. L., Chen B., Schiffhauer L., Cullinan J., Ning Y., and Robinson A. E., “Flat-panel-detector-based cone-beam volume CT breast imaging: Phantom and specimen study,” Proc. SPIE 4682, 218–227 (2002). 10.1117/12.465562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B. and Ning R., “Cone-beam volume CT breast imaging: Feasibility study,” Med. Phys. 29, 755–770 (2002). 10.1118/1.1461843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Lindfors K. K., and Seibert J. A., “Dedicated breast CT: Radiation dose and image quality evaluation,” Radiology 221, 657–667 (2001). 10.1148/radiol.2213010334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Kwan A. L., Seibert J. A., Shah N., Lindfors K. K., and Nelson T. R., “Technique factors and their relationship to radiation dose in pendant geometry breast CT,” Med. Phys. 32, 3767–3776 (2005). 10.1118/1.2128126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindfors K. K., Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Yang K., Kwan A. L., and Miller D. F., “Dedicated breast CT: Initial clinical experience,” Radiology 246, 725–733 (2008). 10.1148/radiol.2463070410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant D. G., “Tomosynthesis: A three-dimensional radiographic imaging technique,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. BME-19, 20–28 (1972). 10.1109/TBME.1972.324154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J. T.DobbinsIII and Godfrey D. J., “Digital x-ray tomosynthesis: Current state of the art and clinical potential,” Phys. Med. Biol. 48, R65–R106 (2003). 10.1088/0031-9155/48/19/R01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Stewart A., Stanton M., McCauley T., Phillips W., Kopans D. B., Moore R. H., Eberhard J. W., Opsahl-Ong B., Niklason L., and Williams M. B., “Tomographic mammography using a limited number of low-dose cone-beam projection images,” Med. Phys. 30, 365–380 (2003). 10.1118/1.1543934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklason L. T. et al. , “Digital tomosynthesis in breast imaging,” Radiology 205, 399–406 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette M. et al. , “Digital breast tomosynthesis using an amorphous selenium flat panel detector,” Proc. SPIE 5745, 529–542 (2005). 10.1117/12.601622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karellas A., Lo J. Y., and Orton C. G., “Point/Counterpoint: Cone beam x-ray CT will be superior to digital x-ray tomosynthesis in imaging the breast and delineating cancer,” Med. Phys. 35, 409–411 (2008). 10.1118/1.2825612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertelmeier T., Orman J., Haerer W., and Dudam M. K., “Optimizing filtered backprojection reconstruction for a breast tomosynthesis prototype device,” Proc. SPIE 6142, 61420F (2006). 10.1117/12.651380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byng J. W., Boyd N. F., Fishell E., Jong R. A., and Yaffe M. J., “The quantitative analysis of mammographic densities,” Phys. Med. Biol. 39, 1629–1638 (1994). 10.1088/0031-9155/39/10/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempau J., Fernández-Varea J. M., Acosta E., and Salvat F., “Experimental benchmarks of the Monte Carlo code,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 207, 107–123 (2003). 10.1016/S0168-583X(03)00453-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R., Samei E., Badea C., Yuan H., Ghaghada K., Qi Y., Hedlund L. W., and Mukundan S., “Optimization of dual energy contrast enhanced breast tomosynthesis for improved mammographic lesion detection and diagnosis,” Proc. SPIE 6913, 69130Y (2008). 10.1117/12.772042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Fewell T. R., and Jennings R. J., “Molybdenum, rhodium, and tungsten anode spectral models using interpolating polynomials with application to mammography,” Med. Phys. 24, 1863–1874 (1997). 10.1118/1.598100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J., Mertelmeier T., Kunze H., and Härer W., “A novel approach for filtered backprojection in tomosynthesis based on filter kernels determined by iterative reconstruction techniques,” (cited as conference proceedings in a book chapter): Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Digital Mammography (Tucson, AZ), edited by Krupinski Elizabeth A., LNCS 5116 (Springer, Berlin, 2008), pp. 612–620.

- Tukey J. W., “Comparing individual means in the analysis of variance,” Biometrics 5, 99–114 (1949). 10.2307/3001913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carton A. K., Gavenonis S. C., Currivan J. A., Conant E. F., Schnall M. D., and Maidment A. D., “Dual-energy contrast-enhanced digital breast tomosynthesis—A feasibility study,” Br. J. Radiol. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carton A. -K., Ullberg C., Lindman K., Francke T., and Maidment A., “Optimization of a dual-energy contrast-enhanced technique for a photon counting digital breast tomosynthesis system,” (cited as conference proceedings in a book chapter): Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Digital Mammography (Tucson, AZ), edited by Krupinski Elizabeth A., LNCS 5116 (Springer, Berlin, 2008), pp. 116–123.

- Puong S., Patoureaux F., Iordache R., Bouchevreau X., and Muller S., “Dual-energy contrast enhanced digital breast tomosynthesis: Concept, method, and evaluation on phantoms,” Proc. SPIE 6510, 65100U (2007). 10.1117/12.710106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Puong S., Bouchevreau X., Duchateau N., Iordache R., and Muller S., “Optimization of beam parameters and iodine quantification in dual-energy contrast enhanced digital breast tomosynthesis,” Proc. SPIE 6913, 69130Z (2008). 10.1117/12.770148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakic P. R., Carton A. K., Kontos D., Zhang C., Troxel A. B., and Maidment A. D., “Breast percent density: Estimation on digital mammograms and central tomosynthesis projections,” Radiology 252, 40–49 (2009). 10.1148/radiol.2521081621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos D., Bakic P. R., Carton A. K., Troxel A. B., Conant E. F., and Maidment A. D., “Parenchymal texture analysis in digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer risk estimation: A preliminary study,” Acad. Radiol. 16, 283–298 (2009). 10.1016/j.acra.2008.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer C. M., Samei E., Saunders R. S., Zerhouni M., and Lo J. Y., “Toward quantification of breast tomosynthesis imaging,” Proc. SPIE 6913, 6913N (2008). [Google Scholar]