Abstract

Physiological and anatomical investigations are commonly combined in experimental models. When studying the lower urinary tract (LUT), it is often of interest to perform both urodynamic studies and retrogradely labeled neurons innervating the peripheral target organs. However, it is not known whether the use of anatomical tracers for the labeling of e.g. spinal cord neurons may interfere with the interpretation of the physiological studies on micturition reflexes. We performed cystometry and external urethral sphincter (EUS) electromyography (EMG) under urethane anesthesia in adult female rats at 5-7 days after injection of a 5% fluorogold (FG) solution or vehicle into the major pelvic ganglia (MPG) or the EUS. FG and vehicle injections into the MPG and EUS resulted in decreased voiding efficiency. MPG injections increased the duration of both bladder contractions and the inter-contractile intervals. EUS injections decreased EUS EMG bursting activity during voiding as well as increased both the duration of bladder contractions and the maximum intravesical pressure. In addition, the bladder weight and size were increased after either MPG or EUS injections in both the FG and vehicle groups. We conclude that the injection of anatomical tracers into the MPG and EUS may compromise the interpretation of subsequent urodynamic studies and suggest investigators to consider experimental designs, which allow for physiological assessments to precede the administration of anatomical tracers into the LUT.

Keywords: Fluorogold, major pelvic ganglion, autonomic preganglionic neuron, motoneuron

Introduction

It is commonly of interest to determine both the functional state and anatomical innervation of the lower urinary tract (LUT). Such combined assessments are of particular importance following injury and repair of, for instance, lumbosacral ventral roots and the peripheral nerves, which innervate the pelvic ganglia and external urethral muscle (Chang and Havton, 2008; Damaser et al., 2007; Hoang et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2009a,b; Kerns et al., 2000). For this purpose, urodynamic studies are commonly used to determine physiologic properties of the LUT. Specifically, cystometry (CMG) is performed to examine contractile properties of the bladder and its reflex functions. Electromyography (EMG) of the external urethral sphincter (EUS) may be performed to study somatic motor unit activity of the urethral sphincter during the bladder filling phase and voiding. To determine anatomical connectivity between subsets of spinal cord neurons and the LUT, retrogradely transported tracers are typically injected into the peripheral targets. A variety of anatomical tracers have been injected into e.g. pelvic autonomic ganglia and the EUS (Harji et al., 1998; Hoang et al., 2006; Hosoya et al., 1994; Pikov and Wrathall, 2001). However, it is not well understood how to best combine the anatomical and physiological studies in the same subject. Specifically, it is not known whether injection of an anatomical tracer into the LUT or the intracellular presence of a tracer substance in labeled neurons may compromise the interpretation of detailed urodynamic studies.

Therefore, we injected the retrogradely transported tracer fluorogold (FG) into the major pelvic ganglia (MPG) and the EUS in rats to investigate its effect on urodynamic studies, including CMG and EUS EMG recordings. FG was chosen as a tracer because of its versatility as a tracer and wide-spread use in the neuroscience community. For instance, FG is readily detected in retrogradely labeled neurons by epifluorescence microscopy (Schmued et al., 1989). Immunohistochemistry, using an antibody to FG, allows for a light stable reaction product and detection in the light microscope (Akhavan et al., 2006; Hoang et al., 2003). FG-labeled neurons may also be detected in the electron microscope using a recently developed post-embedding immuno-gold protocol (Persson and Havton, 2009).

We demonstrate that FG and vehicle injections into the MPG and EUS adversely affect micturition reflexes with an overall decrease in voiding efficiency (VE). Specifically, the contractile properties of the bladder were compromised by both the MPG and EUS injections, whereas EUS bursting activity during voiding was reduced only by injections into the EUS. In addition, bladder weight and size were increased after FG and vehicle injections into both the MPG and EUS.

Experimental Procedures

A total of 33 adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (252 ± 7 g, Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC) were included in the study. The animals were divided into five experimental groups based on method of tracer and vehicle injections: 1) FG injection into the bilateral MPG (MPG/FG rats, n=6); 2) Sterile water vehicle injection into the bilateral MPG (MPG/W rats, n=6); 3) FG injection into the EUS (EUS/FG rats, n=7); 4) Sterile water vehicle injection into the EUS (EUS/W, n=7); 5) Naïve rats without any tracer or vehicle injection (control rats, n=7). All animal procedures were performed according to the standards established by the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23, revised 1996). The experimental protocols were approved by the Chancellor’s Animal Research Committee at UCLA. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Retrograde pre-labeling of spinal cord neurons

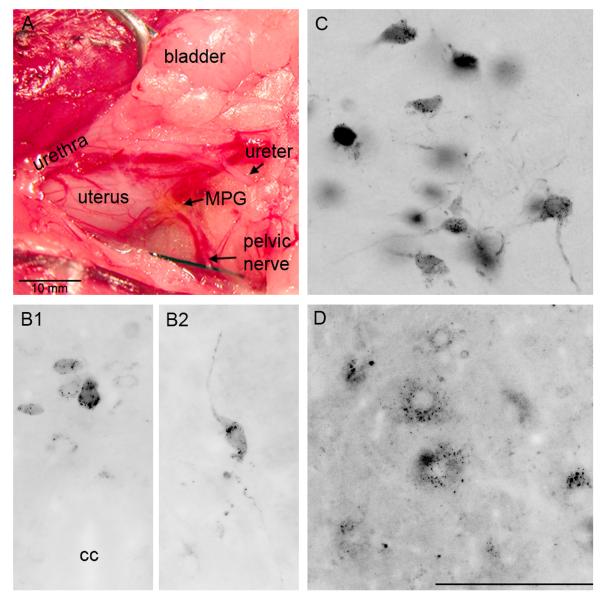

Under gas anesthesia (isoflurane, 2-2.5 %), a midline abdominal incision was made in the rats of the MPG/FG and MPG/W groups. Pelvic nerves were found bilaterally using a combination of anatomical landmarks, including the ureter and urethra (Chang et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2007). The MPG was identified at the distal portion of the pelvic nerve (Fig. 1A). In the MPG/FG rats, 1.0 μl of a 5% FG solution in sterile water was slowly injected manually into the MPG using a 32 gauge needle connected to a 10 μl Hamilton syringe. Following the tracer injection, the needle was held in place for 1 minute before being withdrawn. The injection site was next rinsed with saline. No significant bleeding took place. In the MPG/W group, 1.0 μl of sterile water was similarly injected into MPG instead of FG solution. No significant bleeding or leakage of tracer took place. The muscle and skin were closed in layers and the animals were allowed to recover. Under gas anesthesia (isoflurane, 2-2.5 %), a low abdominal incision was made in the rats of the EUS/FG and EUS/W groups. Along the bladder and bladder neck, the EUS was then identified. In the EUS /FG rats, a total of 1.5 μl of a solution containing 5% FG (Fluorochrome, Denver, CO, USA) in sterile water was injected manually into 3 sites of the EUS using a 32-gauge needle attached to a 10 μl Hamilton syringe. Following the tracer injection, the needle was held in place for 1 minute before being withdrawn. The injection site was next rinsed with saline. In the EUS/W group, a total 1.5 μl of sterile water was injected into 3 sites of the EUS. The muscle and skin were closed in layers, and all animals were allowed to recover. Buprenex® (0.045 mg subcutaneously, Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceutical Inc., Richmond, VA, USA) was given every 12 hours for 48 hours for pain control post-operatively. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole oral suspension, USP (40mg/200mg per 5 ml, Hi-tech Pharmacal Co., Inc., Amityville, NY, USA) was added into drinking water (1 ml of oral suspension per 100 ml drinking water) for 10 days post-operatively. All animals underwent urodynamic experiments before the termination of studies. In the age-matched control rats, no FG or vehicle was administered.

Fig. 1.

Major pelvic ganglion (MPG) was identified by ureter, urethra and pelvic nerve. A 5% fluorogold (FG) solution was injected into MPG (A). Retrogradely labeled sympathetic neurons were found in the dorsal commissural nucleus (B1) and intermediolateral nucleus (B2) of L1-L2 spinal segments in MPG/FG rats. Retrogradely labeled parasympathetic neurons were shown in S1 of spinal cord in MPG/FG rats (C). Retrogradely labeled motoneurons were mainly found in the dorsolateral nucleus of EUS/FG rats (D). The calibration bar in D indicates 100 μm in B1, B2, C and D. cc, central canal.

Urodynamic recordings

All animals underwent urodynamic recordings at 5-7 days after tracer or vehicle injection. For this purpose, rats were anesthetized by a subcutaneous injection of urethane (1.2 g/kg) and placed on a heating pad to maintain the body temperature at 37 °C. The loss of the toe pinch reflex was used to determine a surgical level of anesthesia. To prepare the animals for urodynamic recordings, the urinary bladder was exposed by a midline abdominal incision. A catheter (PE-50) was inserted through the top of the bladder to measure intravesical pressure (IVP) of the bladder. The bladder catheter was connected to a pressure transducer and an infusion pump for CMG. The bladder was continuously infused with saline (0.12 ml/min) at room temperature. For recording EUS EMG activity, two 50 μm epoxy-coated platinum-iridium wire electrodes (A-M Systems, Everett, WA, USA) were hooked at the tip of a 27-gauge needle and inserted into both sides of the EUS. The needle was withdrawn, and the electrodes were left embedded in the muscle. The abdominal incision was closed, while allowing the bladder catheter and two wire electrodes to exit and connect to a personal computer. CMG and EUS EMG data were amplified and digitized (CMG at 5 samples/sec and EUS EMG at 6250 samples/sec) by using a 12-bit data acquisition system (DataLab 2000, Model 70754, Lafayette Instruments, Lafayette, IN, USA). The urodynamic recording sessions lasted for 3-4 hours for each animal (Chang and Havton, 2008a; Chang and Havton, 2008b; Hoang et al., 2006).

Perfusion and tissue preparation

All rats were intravascularly perfused with 200 ml of phosphate buffer saline followed by 400 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (pF) at 1-2 hours after the completion of the urodynamic recordings. The spinal cord were removed, postfixed in 4% pF for 24 hours, and transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for 24 hours. All tissues were dissected, blocked and stored in a − 80 °C freezer. Transverse sections (40 μm) of the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal segments in MPG/FG and EUS/FG groups were cut by using a cryostat. FG-labeled cells were readily detected in wet sections using a Nikon E600 light microscope equipped for epifluorescence microscopy. Next, the sections were processed for immunohistochemical detection of FG to augment the signal of any occasional faintly labeled cells. Primary antibodies were diluted in 0.3% Triton X-100/Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) to increase tissue permeability. The sections were rinsed in PBS, and incubated 1h with 5% normal donkey serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at room temperature as well as overnight with rabbit anti-FG antibody (1:200, Fluorochrome) at 4°C. All sections were then rinsed in PBS and placed in secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor 594; 1:500; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 h at room temperature. All sections were then rinsed in PBS, mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and examined in a Nikon E600 light microscope equipped for epifluorescence microscopy. Images were captured with a Spot RT-slider monochrome camera (Diagnostics Instruments, Sterling heights, MI) attached to the microscope. Following the intravascular perfusion, the bladders were blotted dry, weighed, and flattened to measure their length (L) and width (W). The formula [(4/3) × π × L × W2] was used to estimate the bladder volume (Hoang et al., 2006).

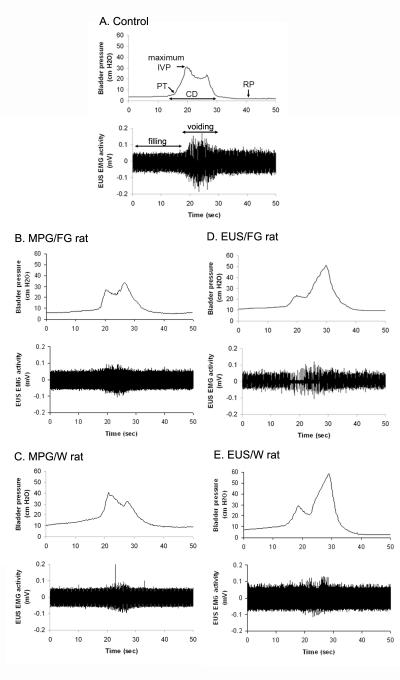

Analysis of urodynamic recordings

In all animals, a minimum of 15 bladder contractions with associated EUS EMG tonic and bursting activity were analyzed. For CMG recordings, maximum IVP and inter-contraction interval (ICI) were determined (Chang and Havton, 2008a; Chang and Havton, 2008b; Maggi et al., 1986a; Maggi et al., 1986b). The pressure threshold (PT), resting pressure (RP) and contraction duration (CD) were also measured (Fig. 2A; Chang and Havton, 2008a; Chang and Havton, 2008b; Maggi et al., 1986a; Maggi et al., 1986b). Voided volume (Vv) was measured in each voiding cycle by collecting urine. The total micturition volume (Vt) was estimated by calculating the product of the ICI and bladder filling rate. VE, the percentage of the bladder volume voided, was then calculated by using the formula (Vv/Vt × 100) (Yoo et al., 2008; Yoshiyama et al., 2005). For the EUS EMG recordings, precise placement of the thin wire electrodes may vary between subjects, affect the recorded amplitude, and may be a source for some variation in baseline amplitude values (Callsen-Cencic and Mense, 1998). Therefore, the baseline fluctuations caused by a low-frequency component of the EMG, generally attributed to activity of the internal urethral sphincter, were filtered out using a baseline zero correction at 100 ms intervals. The EUS EMG activity was rectified and analyzed using custom software written in Visual Basic (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) with Measurement Studio ActiveX components (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). The amplitudes of EUS tonic and bursting activity during bladder filling and voiding were calculated (Chang and Havton, 2008a; Chang and Havton, 2008b; Hoang et al., 2006). The frequency of bursts of EUS bursting was calculated as the number of individual bursts per second (Chang and Havton, 2008b; Cheng and de Groat, 2004). As a marker for the coordinated function of the bladder and EUS, the latency between the PT of the bladder contraction and the onset of EUS tonic activity (CMG-EUS latency) during the same voiding cycle was determined (Chang and Havton, 2008a).

Fig. 2.

Representative examples of bladder pressure and EUS EMG activity. Control recording and parameters were shown in (A). The recordings in MPG/FG and MPG/W rats were presented in (B) and (C), respectively. The recordings in EUS/FG and EUS/W rats were presented in (D) and (E), respectively. CD, contraction duration; IVP, intravesical pressure; PT, pressure threshold; RP, resting pressure.

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard error. To assess for differences between the three groups, the One Way Analysis of Variance was applied. The Student-Newman-Keuls Method was used for the multiple comparison procedures. We considered p<0.05 as indicating statistically significant differences between groups.

Results

Combined CMG and EUS EMG recordings were performed to study micturition reflexes in rats after retrograde FG-labeling of parasympathetic preganglionic neurons (PPNs), sympathetic preganglionic neurons (SPNs) and dorsolateral (DL) motoneurons. For this purpose, a FG solution was injected into the bilateral MPG or the EUS in female rats, and 5-7 days were allowed for retrograde transport of the tracer before the urodynamic studies. In parallel subsets of animals, sterile water was injected into the MPG or the EUS for vehicle control purposes. Naïve age-matched rats without tracer or vehicle injection served as intact controls.

Voiding behavior observations

All animals receiving FG or vehicle injection into the MPG and EUS were monitored closely post-operatively. All rats recovered well after the procedure and were examined for signs of urinary retention. A modest but transient urinary retention was detected by manual bladder expressions in some rats in the immediate post-operative period for all groups but always resolved within 24-48 hours after the surgery. No rats showed urinary retention at the time of the urodynamic studies.

Effects of MPG injections

Rats of both the MPG/FG (n=6) and MPG/W (n=6) series showed a decline in voiding function compared to control rats (n=7) (Table 1). Both groups exhibited significantly reduced VE with CMG recordings showing prolonged ICI and CD. In addition, EMG recordings in MPG/FG rats demonstrated increased amplitude of EUS tonic activity during the filling phase. Both MPG/FG and MPG/W rats showed a marked end organ effect with increased bladder volume and weight compared to controls.

Table 1.

Parameters of CMG and EUS EMG activity in control rats as well as MPG/FG and MPG/W rats.

| Control rats | MPG/FG rats | MPG/W rats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| VE, % | 83 ± 1 | 67 ± 6* | 65 ± 3* |

| Cystometry | |||

| ICI, s | 59 ± 6 | 83 ± 10* | 65 ± 3* |

| CD, s | 23 ± 1 | 58 ± 9* | 45 ± 4* |

| maximum IVP, cmH2O | 29 ± 1 | 32 ± 6 | 40 ± 5* |

| PT, cmH2O | 6 ± 0.4 | 7 ± 0.8 | 8 ± 0.5 |

| RP, cmH2O | 2 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.1 | 2 ± 0.1 |

| EUS EMG activity | |||

| EUS tonic activity, mV | 0.064 ± 0.008 | 0.100 ±0.007*,† | 0.061 ± 0.003 |

| EUS bursting, mV | 0.131 ± 0.019 | 0.127 ± 0.029 | 0.118± 0.013 |

| frequency of bursts, Hz | 6 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.5 |

| Co-ordination | |||

| CMG-EMG latency, s | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.007 | 0.21 ± 0.01 |

| Bladders | |||

| bladder volume, ml | 1.08 ± 0.328 | 1.567 ± 0.002* | 1.437 ± 0.151* |

| bladder weight, mg | 79 ± 2 | 112 ± 8* | 94 ± 4* |

Values are means ± SE. VE, voiding efficiency; ICI, intercontraction intervals; CD, contraction duration; IVP, intravesical pressure; PT, pressure threshold; RP, resting pressure.

P < 0.05, significantly compared to control rats.

P < 0.05, significantly changed compared to MPG/W rats.

Effects of EUS injections

Rats of both the EUS/FG (n=7) and EUS/W (n=7) series showed reduced voiding function compared to control rats (n=7) (Table 2). Both groups showed significantly reduced VE with markedly reduced EUS EMG bursting activity during voiding compared to controls. CMG recordings showed increased CD and maximum IVP for both EUS/FG and EUS/W series. In addition, the EUS/W rats demonstrated a significantly higher PT compared to the EUS/FG and control groups.

Table 2.

Parameters of CMG and EUS EMG activity in control rats as well as EUS/FG and EUS/W rats.

| Control rats | EUS/FG rats | EUS/W rats | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| VE, % | 83 ± 1 | 67 ± 3* | 63 ± 3* |

| Cystometry | |||

| ICI, s | 59 ± 6 | 55 ± 3 | 72 ± 8*,† |

| CD, s | 23 ± 1 | 33 ± 2* | 37 ± 1* |

| maximum IVP, cmH2O | 29 ± 1 | 58 ± 10* | 62 ± 9* |

| PT, cmH2O | 6 ± 0.4 | 6 ± 0.3 | 9 ± 1.1*,† |

| RP, cmH2O | 2 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0.3 |

| EUS EMG activity | |||

| EUS tonic activity, mV | 0.064 ± 0.008 | 0.060 ± 0.008 | 0.067 ± 0.006 |

| EUS bursting, mV | 0.131 ± 0.019 | 0.084 ± 0.009* | 0.098 ± 0.012* |

| frequency of bursts, Hz | 6 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.3 |

| Co-ordination | |||

| CMG-EMG latency, s | 0.227 ± 0.011 | 0.201 ± 0.012 | 0.196 ± 0.014 |

| Bladders | |||

| bladder volume, ml | 1.082 ± 0.328 | 1.769 ± 0.194* | 1.433 ± 0.167* |

| bladder weight, mg | 79 ± 2 | 108 ± 5* | 99 ± 5* |

Values are means ± SE. VE, voiding efficiency; ICI, intercontraction intervals; CD, contraction duration; IVP, intravesical pressure; PT, pressure threshold; RP, resting pressure.

P < 0.05, significantly changed compared to control rats.

P < 0.05, significantly increased compared to control and EUS/FG rats.

Retrograde FG labeling

To confirm successful labeling of efferent spinal cord neurons in rats of the experimental series, the L1-L2 and L6-S1 spinal segments of the MPG/FG and EUS/FG rats were sectioned for epifluorescence microscopy. Retrogradely labeled SPNs were mostly found in the dorsal commissural nucleus (DCN, Fig.1, B1) but also in the intermediolateral (IML, Fig.1, B2) nucleus of L1-L2 spinal segments in MPG/FG rats. Retrogradely labeled PPNs were consistently demonstrated in the IML nucleus of the L6-S1 segments in MPG/FG rats (Fig. 1C), and retrogradely labeled motoneurons were found in the DL nucleus of EUS/FG rats (Fig. 1D).

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the effect of FG tracer injection into the MPG and EUS on the LUT in adult rats. For this purpose, we performed urodynamic studies in adult female rats, and outcome measures were obtained from CMG recordings, EUS EMG activity, and bladder size measurements. We demonstrate that both FG and vehicle injections into the MPG and EUS result in decreased VE compared to corresponding assessments in naïve controls. The urodynamic studies also showed that injections into the MPG predominantly alter the contractile properties of the bladder, whereas EUS injections affect both the voiding-associated bursting activity of the EUS and the bladder contractile properties. Interestingly, all groups receiving injection of either FG or vehicle into the MPG or EUS demonstrated a marked increase in their bladder weight and size.

Methodological considerations

For the present studies, standard protocols were used for tracer injections into the MPG and EUS and validated by the presence of retrogradely labeled neurons in the appropriate locations within the lumbosacral spinal cord. In previous morphological investigations on retrogradely labeled neurons, FG has been injected into muscle or applied to the cut end of a peripheral nerve in rats as a 2-10% solution in sterile water or saline (Hoang et al., 2006; Khristy et al., 2009; Novikova et al., 1997; Puigdellívol-Sánchez et al., 2002). Although 4-7 days are typically allowed to retrogradely label the somata of spinal motoneurons, FG may also be used for long-term pre-labeling studies (Akhavan et al., 2006). For retrograde labeling of neurons innervating the LUT, prior studies have injected 2-5 μl of tracer solutions into the MPG in male rats (Hinrichs and Llewellyn-Smith, 2009; Santer et al., 2002) 2-50 μl of tracer solution into the EUS (Hoang et al., 2006; Pikov and Wrathall, 2001). Thus, protocols used for tracer injections here are consistent with those used in an extensive body of prior studies.

Previous studies have suggested that FG may result in degenerative changes, which may be most readily detected in labeled neurons at prolonged post-injection time points (Naumann et al., 2000). However, long–term studies of FG-labeled motoneurons and autonomic preganglionic neurons did not show any detectable loss of the retrogradely labeled neurons up to 12 weeks after parenteral tracer administration (Akhavan et al., 2006). In the present studies, similar adverse effects on functional outcome measures were detected in both FG and vehicle injection groups, thereby suggesting that the observed functional compromise may be related to the injection procedure and not to the tracer itself.

MPG injections in female rats

Both parasympathetic and sympathetic postganglionic neurons are located in the MPG of rats, extend their axons to adjacent visceral organs and innervate the bladder, distal colon, and reproductive organs (Keast et al., 1989). However, sexual dimorphism exists with regards to the anatomical location and features of the MPG in rats. In male rats, the MPG is a prominent and anatomically distinct structure, which is readily accessible for e.g. tracer injections. As a result, a variety of anatomical markers have been injected into the MPG of male rats to retrogradely labeled preganglionic parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons in the spinal cord (Baron and Jänig, 1991; Hosoya et al., 1994; Nadelhaft and McKenna, 1987). In contrast, the MPG of female rats is much less prominent anatomically but may be identified at the distal end of the pelvic nerve, adjacent to the uterine wall. Although the MPG has been subjected to experimental manipulations and studies in rats of both genders (Persson et al.,1998; Vera and Meyer-Siegler, 2003), there has been a paucity of investigations attempting anatomical tracer injections into the MPG in female rats. Here, we demonstrate a practical surgical approach to identify the MPG and inject a tracer substance for retrograde labeling of autonomic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord of female rats.

Tracer injections affect urodynamic recordings

The functional properties of reflexive micturition were affected by both MPG and EUS injections. Following tracer and vehicle injections into the MPG, the VE was reduced with primary urodynamic abnormalities detected as cystometric lengthening of the ICI and a prolonged CD. As the MPG is innervated by both parasympathetic and sympathetic preganglionic neurons (Baron and Jänig, 1991; Hosoya et al., 1994), it may appear reasonable that the autonomic functions of the bladder were also predominantly affected by the injection procedure. In contrast, tracer and vehicle injections into the EUS also resulted in decreased VE, which was associated with decreased EUS bursting activity during the voiding phase. This finding is likely functionally relevant, as EUS bursting activity is important for voiding function and a lack of EUS EMG activity is associated with reduced VE (Chang et al., 2006; Chang et al., 2007; Cheng and de Groat, 2004; Maggi et al., 1986a; Maggi et al., 1986b; Peng et al., 2008). For comparison, EUS EMG activity may also be reduced or eliminated after pudendal nerve injury by crush, transection, or vaginal distension (Kerns et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2009a, b) as well as after a lumbosacral ventral root avulsion injury (Hoang et al., 2006). In the present studies, the maximum IVP and CD were also increased after EUS injections, possibly representing a secondary effect due to post-injection swelling of the EUS causing increased urethral resistance to urinary flow.

Our findings show that tracer injections into the peripheral target organs of the LUT may represent a confounding factor for the interpretation of concurrent urodynamic studies. However, the studies do not determine whether a needle injection alone, without injection of a tracer or vehicle solution into ganglion and muscle targets of the lower urinary tract, is sufficient to compromise urodynamic function. Investigators wishing to combine retrograde labeling of neurons and urodynamic investigations thus face some specific limitations associated with combined anatomical and physiological studies. For instance, injections of anatomical tracers into peripheral organs for retrograde labeling of neurons typically need 4-7 days of retrograde transport time and thus need to be performed as part of a survival surgery procedure. Because the tracer injection may change the physiological properties of the detrusor and EUS, urodynamic studies are often preferably completed before tracer injections and by necessity performed as a survival procedure. For this purpose, anesthesia is typically required for the placement of the bladder catheter and EMG electrodes as well as to immobilize the animal during the CMG and EUS EMG recordings. Importantly, available anesthetics have different properties and may be more or less suited for urodynamic studies in experimental models (Cannon and Damaser, 2001; Morikawa et al., 1989; Yokoyama et al., 1997). For instance, isoflurane, a gas inhalation anesthetic, is commonly used for survival surgery procedures, but it suppresses EUS EMG activity and prolongs the intervals between reflex bladder contractions more than urethane, an injectable anesthetic (Chang and Havton, 2008a). However, urethane is commonly not recommended for survival procedures in rats due to its side effect profile (Field and Lang, 1988). In previous studies on cauda equina injury and repair in rats, we combined anatomical and physiological studies of the LUT and performed urodynamic studies under isoflurane anesthesia prior to the injection of an anatomical tracer for retrograde labeling of spinal cord neurons (Chang and Havton, 2008a; Hoang et al., 2006). Although the latter studies may have provided a conservative underestimation of the degree of functional reinnervation after a bilateral lumbosacral ventral root avulsion injury and replantation, the potential confounding effect of tracer injections was avoided.

Tracer injections affects bladder size and weight

The size and weight of the urinary bladder may change in response to neurological injuries in animal models, and such end organ responses have been well characterized after, for instance, traumatic injuries to the spinal cord. The severity of a traumatic spinal cord injury is an important determinant of the peripheral end organ responses, as weight drop contusion injuries with the least degree of white matter sparing at the segmental level of injury showed the most increase in bladder weight and size (Pikov and Wrathall, 2001). A lower motoneuron injury, in the form of a bilateral lumbosacral ventral root avulsion injury also resulted in urinary retention as well as increased bladder weight and size (Hoang et al., 2006). In the present investigation, we demonstrate markedly increased bladder weight and size, but in the absence of any urinary retention, after injection of the FG tracer solution or vehicle into the MPG or EUS. Interestingly, the end organ response was present at the relatively early time point of 5-7 days after the injection. Tracer and vehicle injections to MPG resulted in an increase of ICI and CD as well as a decrease VE. For comparison, tracer and vehicle injections to EUS resulted in an increased CD and maximum IVP as well as weak EUS bursting activity. Thus, we encountered signs suggestive of a larger bladder capacity, weak stream and/or increased urethral resistance. Such changes have previously been associated with the syndrome of partial bladder outflow obstruction (Berggren and Uvelius, 1998; Saito et al., 1997). We find that bladder size and weight represent sensitive markers for experimental manipulation of the LUT, especially as no rats showed any clinical signs of urinary retention.

Conclusion

We conclude that micturition reflexes as well as bladder size and weight are affected by tracer or vehicle injections into the MPG and EUS in rats. We suggest that investigators exert caution when combining anatomical studies of the LUT, using the injection of retrogradely transported tracers, with physiological assessments of micturition reflexes. Our studies also suggest that bladder size and weight assessments may be used as a sensitive indicator of subclinical dysfunction of micturition in rat models.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NS042719) and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation.

Comprehensive list of abbreviations

- CD

contraction duration

- CMG

cystometry

- DCN

dorsal commissural nucleus

- DL

dorsolateral

- EMG

electromyography

- EUS

external urethral sphincter

- FG

fluorogold

- ICI

inter-contraction interval

- IML

intermediolateral

- IVP

intravesical pressure

- L

length

- LUT

lower urinary tract

- MPG

major pelvic ganglion

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- pF

paraformaldehyde

- PPNs

parasympathetic preganglionic neurons

- PT

pressure threshold

- RP

resting pressure

- SPNs

sympathetic preganglionic neurons

- VE

voiding efficiency

- Vt

total volume

- Vv

voided volume

- W

width

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Akhavan M, Hoang TX, Havton LA. Improved detection of fluorogold-labeled neurons in long-term studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;152:156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron R, Jänig W. Afferent and sympathetic neurons projecting into lumbar visceral nerves of the male rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;314:420–436. doi: 10.1002/cne.903140302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berggren T, Uvelius B. Cystometrical evaluation of acute and chronic overdistension in the rat urinary bladder. Urol Res. 1998;26:325–330. doi: 10.1007/s002400050064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callsen-Cencic P, Mense S. Abolition of cystitis-induced bladder instability by local spinal cord cooling. J Urol. 1998;160:236–241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon TW, Damaser MS. Effects of anesthesia on cystometry and leak point pressure of the female rat. Life Sci. 2001;69:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang HY, Cheng CL, Chen JJ, de Groat WC. Roles of glutamatergic and serotonergic mechanisms in reflex control of the external urethral sphincter in urethane-anesthetized female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R224–R234. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00780.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang HY, Cheng CL, Chen JJ, de Groat WC. Serotonergic drugs and spinal cord transections at different levels indicate that different spinal circuits are involved in tonic and bursting external urethral sphincter activity in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292:F1044–F1053. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00175.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang HY, Havton LA. Differential effects of urethane and isoflurane on external urethral sphincter electromyography and cystometry in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1248–F1253. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90259.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang HY, Havton LA. Re-established micturition reflexes show differential activation patterns after lumbosacral ventral root avulsion injury and repair in rats. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng CL, de Groat WC. The role of capsaicin-sensitive afferent fibers in the lower urinary tract dysfunction induced by chronic spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2004;187:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damaser MS, Samplaski MK, Parikh M, Lin DL, Rao S, Kerns JM. Time course of neuroanatomical and functional recovery after bilateral pudendal nerve injury in female rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F1614–F1621. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00176.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field KJ, Lang CM. Hazards of urethane (ethyl carbamate): a review of the literature. Lab Anim. 1988;22:255–262. doi: 10.1258/002367788780746331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harji F, Gonzales J, Galindo R, Dail WG. Preganglionic fibers in the rat hypogastric nerve project bilaterally to pelvic ganglia. Anat Rec. 1998;252:229–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199810)252:2<229::AID-AR8>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinrichs JM, Llewellyn-Smith IJ. Variability in the occurrence of nitric oxide synthase immunoreactivity in different populations of rat sympathetic preganglionic neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2009;514:492–506. doi: 10.1002/cne.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoang TX, Nieto JH, Tillakaratne NJ, Havton LA. Autonomic and motor neuron death is progressive and parallel in a lumbosacral ventral root avulsion model of cauda equina injury. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:477–486. doi: 10.1002/cne.10928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoang TX, Pikov V, Havton LA. Functional reinnervation of the rat lower urinary tract after cauda equina injury and repair. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8672–8679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1259-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosoya Y, Nadelhaft I, Wang D, Kohno K. Thoracolumbar sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the dorsal commissural nucleus of the male rat: an immunohistochemical study using retrograde labeling of cholera toxin subunit B. Exp Brain Res. 1994;98:21–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00229105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang HH, Pan HQ, Gustilo-Ashby MA, Gill B, Glaab J, Zaszczurynski P, Damaser M. Dual simulated childbirth injuries result in slowed recovery of pudendal nerve and urethral function. Neurourol Urodyn. 2009a;28:229–235. doi: 10.1002/nau.20632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang HH, Gustilo-Ashby AM, Salcedo LB, Pan HQ, Sypert DF, Butler RS, Damaser MS. Electrophysiological function during voiding after simulated childbirth injuires. Exp Neurol. 2009b;215:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keast JR, Booth AM, de Groat WC. Distribution of neurons in the major pelvic ganglion of the rat which supply the bladder, colon or penis. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;256:105–112. doi: 10.1007/BF00224723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerns JM, Damaser MS, Kane JM, Sakamoto K, Benson JT, Shott S, Brubaker L. Effects of pudendal nerve injury in the female rat. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:53–69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(2000)19:1<53::aid-nau7>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khristy W, Ali NJ, Bravo AB, de Leon R, Roy RR, Zhong H, London NJ, Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ. Changes in GABA(A) receptor subunit gamma 2 in extensor and flexor motoneurons and astrocytes after spinal cord transection and motor training. Brain Res. 2009;1273:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maggi CA, Giuliani S, Santicioli P, Meli A. Analysis of factors involved in determining urinary bladder voiding cycle in urethane-anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1986;251:R250–R257. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1986.251.2.R250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maggi CA, Santicioli P, Meli A. The nonstop transvesical cystometrogram in urethane-anesthetized rats: a simple procedure for quantitative studies on the various phases of urinary bladder voiding cycle. J Pharmacol Methods. 1986;15:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(86)90064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morikawa K, Ichihashi M, Kakiuchi M, Yamauchi T, Kato I, Ito Y, Gomi Y. Effects of various drugs on bladder function in conscious rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;50:369–376. doi: 10.1254/jjp.50.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nadelhaft I, McKenna KE. Sexual dimorphism in sympathetic preganglionic neurons of the rat hypogastric nerve. J Comp Neurol. 1987;256:308–315. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naumann T, Härtig W, Frotscher M. Retrograde tracing with Fluoro-Gold: different methods of tracer detection at the ultrastructural level and neurodegenerative changes of back-filled neurons in long-term studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;103:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novikova L, Novikov L, Kellerth JO. Persistent neuronal labeling by retrograde fluorescent tracers: a comparison between Fast Blue, Fluoro-Gold and various dextran conjugates. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;74:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng CW, Chen JJ, Cheng CL, Grill WM. Role of pudendal afferents in voiding efficiency in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R660–R672. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00270.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Persson K, Alm P, Uvelius B, Andersson KE. Nitrergic and cholinergic innervation of the rat lower urinary tract after pelvic ganglionectomy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;274:R389–R397. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Persson S, Havton LA. Retrogradely transported fluorogold accumulates in lysosomes of neurons and is detectable ultrastructurally using post-embedding immuno-gold methods. J Neurosci Methods. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.07.017. (In Press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puigdellívol-Sánchez A, Valero-Cabré A, Prats-Galino A, Navarro X, Molander C. On the use of fast blue, fluoro-gold and diamidino yellow for retrograde tracing after peripheral nerve injury: uptake, fading, dye interactions, and toxicity. J Neurosci Methods. 2002;115:115–127. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pikov V, Wrathall JR. Coordination of the bladder detrusor and the external urethral sphincter in a rat model of spinal cord injury: effect of injury severity. J Neurosci. 2001;15:559–569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-02-00559.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saito M, Yokoi K, Ohmura M, Kondo A. Effect of ischemia and partial outflow obstruction on rat bladder function. Urol Res. 1997;25:207–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00941984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Santer RM, Dering MA, Ranson RN, Waboso HN, Watson AH. Differential susceptibility to ageing of rat preganglionic neurons projecting to the major pelvic ganglion and their afferent inputs. Auton Neurosci. 2002;96:73–81. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(01)00366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmued LC, Kyriakidis K, Fallon JH, Ribak CE. Neurons containing retrogradely transported Fluoro-Gold exhibit a variety of lysosomal profiles: a combined brightfield, fluorescence, and electron microscopic study. J Neurocytol. 1989;18:333–343. doi: 10.1007/BF01190836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vera PL, Meyer-Siegler KL. Anatomical location of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in urogenital tissues, peripheral ganglia and lumbosacral spinal cord of the rat. BMC Neurosci. 2003;4:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokoyama O, Yoshiyama M, Namiki M, de Groat WC. Influence of anesthesia on bladder hyperactivity induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;273:R1900–R1907. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.6.R1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoo PB, Woock JP, Grill WM. Bladder activation by selective stimulation of pudendal nerve afferents in the cat. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshiyama M, de Groat WC. Supraspinal and spinal alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid and N-methyl-D-aspartate glutamatergic control of the micturition reflex in the urethane-anesthetized rat. Neuroscience. 2005;132:1017–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]