Abstract

Stem cells have emerged as a key element of regenerative medicine therapies due to their inherent ability to differentiate into a variety of cell phenotypes, thereby providing numerous potential cell therapies to treat an array of degenerative diseases and traumatic injuries. A recent paradigm shift has emerged suggesting that the beneficial effects of stem cells may not be restricted to cell restoration alone, but also due to their transient paracrine actions. Stem cells can secrete potent combinations of trophic factors that modulate the molecular composition of the environment to evoke responses from resident cells. Based on this new insight, current research directions include efforts to elucidate, augment and harness stem cell paracrine mechanisms for tissue regeneration. This article discusses the existing studies on stem/progenitor cell trophic factor production, implications for tissue regeneration and cancer therapies, and development of novel strategies to use stem cell paracrine delivery for regenerative medicine.

Keywords: cancer, immune modulation, paracrine actions, stem cells, tissue regeneration, trophic factors

Regenerative medicine therapies, fueled by advances in stem cell biology and technologies, seek to direct inherent nonhealing injuries towards full restoration of tissue structure and subsequent function. Numerous studies have demonstrated that mobilization of endogenous stem cells or exogenous administration of a number of stem cell populations to injured tissues has resulted in structural regeneration of tissue as well as functional improvement. While the original hypothesis underlying stem cell regenerative therapies was based on functional recovery as a consequence of stem cell differentiation, it is now clear that other mechanisms of action are at play. A recent paradigm shift has emerged suggesting that the biomolecules synthesized by stem cells may be as important, if not more so, than differentiation of the cells in eliciting functional tissue repair. The fate of a stem cell is determined by its niche, or local microenvironment, consisting of surrounding cells and the secreted products of the stem cell [1]. Stem cells actively contribute to their environment by secreting cytokines, growth factors and extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules that act either on themselves (autocrine actions) or on neighboring cells (paracrine actions). Therefore, a clearer understanding of stem and progenitor cell biomolecule production may yield new insights into the regulation of cell phenotypes, better define the functional role of stem cells in tissue repair processes and ultimately determine appropriate cell source(s) for specific tissue repair and regeneration applications. As such, current research directions include efforts to elucidate, augment and harness stem cell autocrine and paracrine mechanisms for regenerative medicine.

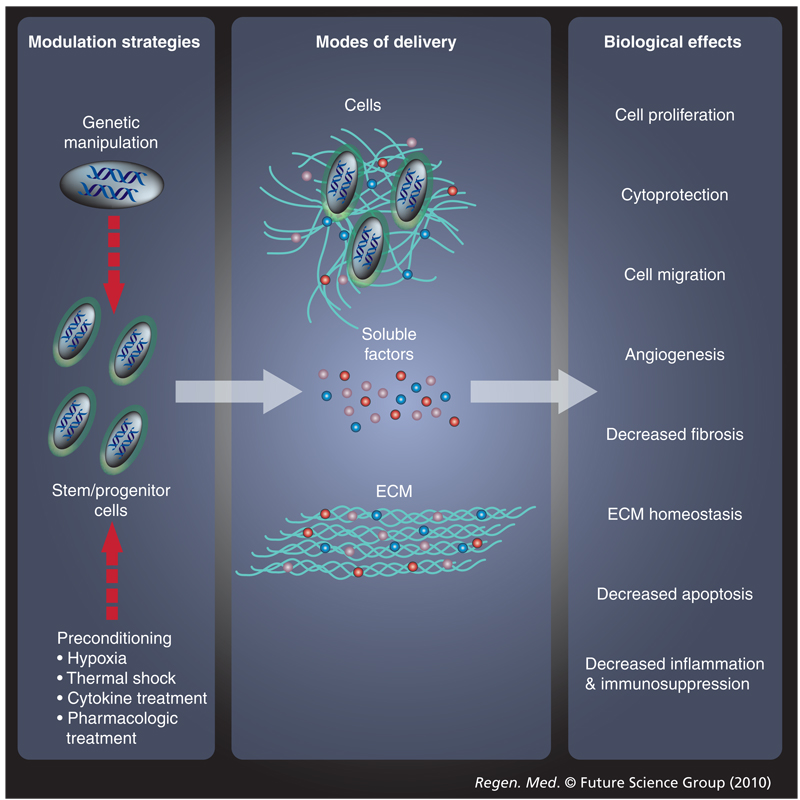

Recent efforts to characterize biomolecule production by stem cells have utilized genomic and proteomic approaches to analyze cell-conditioned media in conjunction with in vitro bioactivity assays [2–6]. Stem cells are capable of producing a broad spectrum of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and ECM molecules. While the majority of published reports to date focus on adult multipotent stem cells (i.e., bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells [BM-MSCs] and hematopoietic stem cells [HSCs]), several studies have also examined pluripotent stem cell (i.e., embryonic stem cell [ESC] and induced pluripotent stem cell [iPSC]) and lineage-restricted progenitor cell (i.e., skeletal myoblast [skMb]) secreted factor production. Growth factors secreted by a number of stem/progenitor cell populations are capable of promoting cell proliferation, cytoprotection and migration. Stem and progenitor cells can also protect other cells from damaging oxygen free radicals through the production of antioxidants and anti-apoptotic molecules. In addition, these cells secrete angiogenic factors, antifibrotic factors, factors responsible for ECM homeostasis such as collagens, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue-derived inhibitors (TIMPs), and anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive factors. Furthermore, stem/progenitor cells not only produce the aforementioned factors, but also consume pro-apoptotic and inflammatory molecules. Since most exogenous cell therapies for tissue repair and regeneration typically involve transplantation of cells into an ischemic environment with varying degrees of inflammation, stem/progenitor cells may also produce a variety of molecules that serve to mediate tissue repair and regeneration via anti-apoptotic, immunosuppressive, proliferative and/or angiogenic mechanisms. Therefore, novel research directions aspire to use stem/progenitor cells as biologically complex drug delivery vehicles to contribute molecular cues to facilitate tissue regeneration (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stem cell paracrine actions can be modulated and administered in different manners to evoke a variety of biological responses

ECM: Extracellular matrix.

The purpose of this review article is to provide an overview of stem/progenitor cell trophic factor production, the implications for tissue regeneration (Table 1) and methods for modulating (Table 2) and harnessing the paracrine actions of these cells. Although a number of stem and progenitor cell populations have been isolated and characterized, the majority of published reports focus on BM-MSCs, due to their wide-spread preclinical and clinical use for tissue regeneration. As a result, the majority of the concepts discussed in this article are based on trophic function of BM-MSCs, but for each application, studies on biomolecule production by other stem/progenitor cell populations have also been included.

Table 1.

Commonly secreted paracrine factors, the organs and disease states they act upon, and their specific functions.

| Secreted factor | Organ system/ disease state |

Functions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ang-1 and -2 | Heart | Angiogenesis | [5,80,81,95] |

| Wound healing | Angiogenesis | ||

| BDNF | Nervous system | Protects dysfunctional motor neurons; increases dopaminergic neuron survival | [47,49–51,54,61,133–135] |

| bFGF | Heart | Cardioprotection; angiogenesis | [5,56,70,71,76,81,90,99,100,102] |

| Wound healing | Enhances granulation tissue thickness, epithelialization and capillary formation | ||

| Bone | Involved in bone formation and repair | ||

| Nervous system | Neuroprotection | ||

| BMP-4 | Nervous system | Determines the lineage specification of NSCs and NPCs | [62,102] |

| Bone | Involved in bone formation and repair | ||

| Collagens | Heart | Re-establishes ECM homeostasis; inhibits fibrosis | [86–89,102] |

| Bone | Regulates bone-related ECM | ||

| GDNF | Nervous system | Protects dysfunctional motor neurons; increases dopaminergic neuron survival | [47,49,50,132] |

| HGF | Immune system | Inhibits T-cell proliferation, cytokine production and cytotoxicity | [5,15,76,80,83,85,89,99,100] |

| Heart | Cardioprotection; angiogenesis; recruits progenitor cells; activates CSCs | ||

| Wound healing | Enhances granulation tissue thickness, epithelialization, and capillary formation | ||

| IDO | Immune system | Inhibits T-cell and NK cell proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxicity; mediates T cell apoptosis | [17,18,27] |

| IGF-1 | Nervous system | Protects dysfunctional motor neurons | [48,69–71,76,82,85,89] |

| Heart | Cardioprotection; angiogenesis; recruits progenitor cells; activates CSCs | ||

| IL-1 | Immune system | Mediates T-cell proliferation | [20,29,32,69,81] |

| Heart | Cardioprotection; angiogenesis | ||

| IL-6 | Immune system | Mediates T-cell proliferation; mediates B-cell proliferation; mediates DC phenotype, maturation, activation and antigen presentation; protects neutrophils from apoptosis | [2,20,23,25,30,109,111,112] |

| Bone marrow | Supports hematopoiesis | ||

| Cancer | Purported role in promoting tumor growth and migration | ||

| IL-7 | Bone marrow | Supports hematopoiesis | [2,5] |

| MMPs | Heart | Re-establishes ECM homeostasis; inhibits fibrosis | [63,87,102,108,112,118] |

| Bone | Regulates bone-related ECM | ||

| Cancer | Purported role in promoting tumor growth and migration | ||

| NGF | Nervous system | Increases dopaminergic neuron survival; determines the lineage specification of NSCs and NPCs | [49,53,56,61] |

| NT-3 | Nervous system | Supports the survival and differentiation of existing neurons; encourages the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses |

[50,54,55] |

| TGF-β | Immune system | Inhibits T-cell and NK cell proliferation, cytokine production and cytotoxicity | [14,15,20,28,54,86,102] |

| Heart | Re-establishes ECM homeostasis; inhibits fibrosis | ||

| Bone | Involved in bone formation and repair | ||

| TIMPs | Heart | Re-establishes ECM homeostasis; inhibits fibrosis | [5,86–88] |

| TNF-α | Heart | Angiogenesis | [15,20,29,32,81] |

| VEGF | Nervous system | Protects dysfunctional motor neurons; determines the lineage specification of NSCs and NPCs | [5,48,56,61,69– 71,80,81,89,90,95,99,100,109,111] |

| Heart | Cardioprotection; angiogenesis | ||

| Wound healing | Angiogenesis; enhances granulation tissue thickness, epithelialization and capillary formation | ||

| Cancer | Purported role in promoting tumor growth and migration |

Ang: Angiopoietin; bFGF: Basic FGF; BMP: Bone morphogenetic protein; CSC: Cardiac stem cell; DC: Dendritic cell; ECM: Extracellular matrix; IDO: Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinase; NK: Natural killer; NPC: Neuronal progenitor cell; NSC: Neural stem cell; NT: Neurotrophin; TIMP: Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase.

Table 2.

Methods to modulate stem cell paracrine actions and resultant outcomes.

| Modification | Organ systems/ disease states |

Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic modification | |||

| Akt | Heart | Increased graft survival; decreased apoptosis, VEGF, IGF-1, bFGF and HGF secretion |

[66,75,76,155] |

| Bcl-2 | Heart | Increased graft survival; decreased apoptosis; increased VEGF secretion |

[130] |

| BDNF | Nervous system | Secretion of neuroprotective factors; decreased apoptosis | [132–135,136,137] |

| BMPs | Bone | Accelerated bone formation and regeneration; angiogenesis | [157–159] |

| GDNF | Nervous system | Secretion of neuroprotective factors | [132–135] |

| HGF | Heart | Increased cell engraftment; increased angiogenesis | [146,148] |

| IFN-β | Cancer | Inhibited tumor growth and angiogenesis | [160–162] |

| IGF-1 | Bone | Accelerated bone formation and regeneration; angiogenesis | [159] |

| IL-2 | Cancer | Delayed tumor growth | [164] |

| NT-3 | Nervous system | Secretion of neuroprotective factors | [132–135] |

| SDF-1 | Heart | Induced stem cell homing to infarcted myocardium, trophic support of cardiomyocytes |

[84,154] |

| VEGF | Heart | Increased cell engraftment; increased angiogenesis; increased myogenic cell commitment |

[84,145,147,150–153,157] |

| Bone | Accelerated bone formation and regeneration; angiogenesis | ||

| Preconditioning | |||

| Hypoxic exposure | Increased expression of VEGF, bFGF, IGF-1 and HGF; increased expression of anti-apoptotic genes; cytoprotection |

[66,70,76,130,169] | |

| Thermal shock induction | Cytoprotection; immune modulation | [172–174] | |

| Pharmacologic treatment | Increased cell survival | [175–179] | |

| Proinflammatory cytokine exposure |

Modulating host immune response | [15,32,37] | |

| Laser treatment | Cytoprotection; immune modulation | [180] | |

| Mechanical conditioning | Modulating ECM synthesis, deposition and mineralization | [181–184] | |

bFGF: Basic FGF; BMP: Bone morphogenetic protein; NT: Neurotrophin; SDF: Stem cell-derived factor.

Stem cell modulation of physiological systems

Stem cell paracrine actions & immune modulation

Human BM-MSCs and embryonic stem cell-derived MSCs (ESC-MSCs) are immunotolerant and may modulate the immune response alone and when co-transplanted with other cell types. MSCs express MHC class I molecules (such as HLA-A, -B and -C), but not MHC class II molecules (such as HLA-DR) or costimulatory molecules (e.g., CD40, CD80 and CD86) [7–10]. Recently, human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs), ESC-MSCs and umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells (UCBs) have also been characterized to share similar surface immunophenotypes [6,11,12]. The immunosuppressive effects of BM-MSCs were first demonstrated in an in vivo model using BM-MSCs to delay rejection of histocompatible skin grafts in a baboon [13]. Since then, research has focused on elucidating the role of these cells in modulating host immune response and, furthermore, on the utility of these cells as ‘protectors’ for other cell types upon cell transplantation.

MSCs & immune cells

It has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo that human BM-MSCs can regulate immune response via cells of both the innate and adaptive immune systems. BM-MSCs influence T-cell, B-cell, natural killer (NK) cell, dendritic cell (DC), macrophage and neutrophil immune activity. Experimental data suggest that MSCs not only inhibit T-cell proliferation, cytokine activity and cytotoxicity (due to BM-MSC secretion of several factors including TGF-β1 [14,15], HGF [15], nitric oxide [16], indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase [IDO] [14,17,18] and prostaglandin E2 [PGE2] [15,19]), but that they also stimulate these cells under certain conditions (through the secretion of cytokines IL-1 and -6 and the chemokine RANTES) [20]. IDO has also been shown to play a role in T-cell apoptosis [18,21]. BM-MSCs inhibit B-cell proliferation, maturation, migration, and immunoglobulin and antibody production [22]. Secretion of IL-6 by BM-MSCs may mediate the inhibitory effects on B-cells; however, the exact molecules and mechanisms responsible have yet to be fully elucidated [23]. MSCs can have an inhibitory effect on immature and mature DC phenotype, maturation, activation and antigen presentation, and these effects are thought in part to be due to BM-MSC IL-6, M-CSF and PGE2 secretion [24–26]. BM-MSCs may modulate immune response through inhibition of DC maturation and subsequent DC inhibition of T-cell proliferation [25]. In addition, BM-MSCs inhibit NK cell proliferation, cytokine production and cytotoxicity through IDO, TGF-β, HLA-G and PGE2 [27,28]. ESC-MSCs have also been implicated in impeding cell lysis by NK cells via the downregulation of cell surface receptors necessary for NK cell activation [12]. More recently, data have emerged suggesting that BM-MSCs play a role in macrophage and neutrophil function. BM-MSC IL-1 receptor agonist secretion inhibits TNF-α production by activated macrophages [29], and IL-6 secretion protects neutrophils from apoptosis [30]. Taken together, these data demonstrate that MSCs act to modulate host immune response and protect other cells from innate and adaptive immune responses.

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation & graft-versus-host disease

Certain stem cell populations can benefit patients undergoing HSC transplantation (HCT) as a result of a hematological disorder or leukemia. It was first determined in the 1970s that mesenchymal stromal cell cultures could support hematopoietic cells in vitro [31], and thus they were subsequently used for this purpose for many years. In recent years, both BM-MSCs and ASCs have been shown to support hematopoiesis (via regulation of hematopoietic cell production) through the secretion of a number of hematopoietic cytokines such as G-CSF, M-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-7 and FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand [2,5]. In addition, BM-MSCs secrete the hematopoietic cytokines IL-12 and -6, and stem cell factor [2]. These data suggest that it may be possible to co-transplant BM-MSCs or ASCs with allogeneic HSCs to treat hematological malignancies and to enhance recovery of immune competence and blood production following aggressive chemotherapy in cancer patients. It should be noted, however, that endogenous or exogenous proinflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1α or -1β, are necessary to elicit the immunosuppressive effects of BM-MSCs [15,32]. Consequently, the immune environment plays an active role in modulating stem cell immunosuppression.

Acute graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) is a major, life-threatening complication that often results from allogeneic HCT. To prevent GvHD, graft recipients often receive immunosuppressive drugs; however, drug suppression is frequently inadequate, and few treatment options exist for severe, treatment-resistant GvHD. Furthermore, global immune suppression can result in complications due to infection and, therefore, local immune suppression is generally preferable. To date, several clinical trials have demonstrated that BM-MSC transplantation can aid HSC engraftment and abate, or in some cases completely resolve, GvHD through reducing severe inflammation [33–36]. However, overall, reports on GvHD prevention with BM-MSC co-transplantation and treatment with BM-MSC administration post-HCT provide conflicting results, suggesting that BM-MSC immunosuppressive ability may depend on the inflammatory environment present in the host. It has been demonstrated that BM-MSCs become active upon exposure to IFN-γ [32]. Therefore, quantifying serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines in graft recipients in order to determine the optimal time for administration of BM-MSCs or ASCs following HCT may prevent or attenuate morbidity and mortality due to GvHD [37].

Autoimmune diseases

Hematopoietic stem cells, BM-MSCs, UCBs and ASCs, given their ability to modulate host immune response, have been proposed as a potential cellular treatment to combat autoimmune diseases such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, autoimmune encephalomyelitis, systemic sclerosis and multiple sclerosis, and several Phase I and II clinical trials are currently ongoing [38–45]. In these cases, it is postulated that local paracrine actions of secreted growth factors (e.g., protection of damaged tissues and transplanted cells) with concurrent local immunosuppression confer therapeutic benefits.

While compelling evidence exists for the role of stem cell paracrine actions in modulating host immune response, further elucidation of the effective amounts of molecules involved, the stimuli for their release and their exact mechanisms of action is necessary. In addition, while most data suggest that stem cells exert an inhibitory effect on host immune cells, some evidence to the contrary exists and has been attributed to differences in stem cell subpopulation and culture conditions [46]. Isolation of a relevant stem/progenitor cell subpopulation and determination of optimal culture conditions may enhance stem cell immunoregulatory action in the treatment of numerous diseases.

Stem cell paracrine actions & tissue regeneration

Although it has been demonstrated in recent years that most organ systems of the body have a resident pool of somatic, tissue-specific stem cells, in many cases of traumatic injury or disease, the quantity and potency of endogenous stem cell populations are insufficient to regenerate compromised tissues. As such, research has focused on exogenous or nontissue-specific stem and progenitor cell sources for tissue repair and regeneration. Initially, efforts to use stem cells for this purpose centered on the directed differentiation of these cells to the intended cell phenotype(s), and functional improvements in a number of tissues were noted with cell transplantation and attributed to stem or progenitor cell differentiation. More recently, however, it has become apparent that many of the functional improvements attributed to stem cells may be due to paracrine actions in the host tissue rather than cell differentiation and repopulation. A resultant shift in research has seen the emergence of studies aiming to elucidate the paracrine mechanisms underlying tissue repair and regeneration with stem or progenitor cell transplantation.

Neuroprotection & neural regeneration

Stem and progenitor cell growth factor secretion has been implicated in repair and regeneration of the CNS following traumatic injury or disease. Recent directions in research on neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease aim to elucidate the production of neurotrophic factors, and subsequent neuroprotective properties of stem cells. There is evidence suggesting that human neural stem cells (NSCs), human UCBs and murine BM-MSCs secrete glial cell- and brain-derived neurotrophic factors (GDNF and BDNF), IGF-1 and VEGF, which may protect dysfunctional motor neurons, thereby prolonging the lifespan of the animal into which they are transplanted in models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [47–51]. In addition, NSCs have been shown to secrete NGF and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) [49,50]. The secretion of GDNF, BDNF and NGF by BM-MSCs has been implicated in increased dopaminergic neuron survival in in vitro and in vivo models of PD, and the release of anti-inflammatory molecules by BM-MSCs has been shown to attenuate microglia activation, thereby protecting dopaminergic neurons from death [52,53]. BM-MSCs and UCBs are also capable of secreting NT-3, which supports the survival and differentiation of existing neurons and encourages the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses [54,55]. In addition, human UCBs secrete antioxidants, NGF, VEGF and basic FGF (bFGF), which may lend to the neuroprotective properties of these cells [54,56].

Stroke-induced damage to the brain and CNS can be caused by focal or global ischemia [57,58]. Focal ischemia, via occlusion of an artery and thrombus formation, leads to infarct formation in the brain and is a common experimental model for studies of stroke [58]. Exogenous BM-MSCs secrete factors that determine the lineage specification of NSCs and neuronal progenitor cells (NPCs). Specifically, as a consequence of various culture conditions, BM-MSCs can differentially release soluble factors that drive NSCs and NPCs to either the neurogenic or astrocytic phenotype [59]. In addition, BM-MSCs secrete trophic factors that provide support to NSC- or NPC-derived neuronal cells in ischemic tissues and promote neurite and axonal outgrowth in vitro and in vivo [59]. Furthermore, transplantation of BM-MSCs into ischemic brain resulted in gain of coordinated function in rats, and it is hypothesized that such an effect is due to BM-MSC soluble factor release resulting in inhibited scar formation and apoptosis, increased angiogenesis and neuronal commitment of NSCs and NPCs [60]. The aforementioned neuroprotective and cell fate effects of BM-MSCs can be attributed to secretion of NGF, VEGF and bone morphogenic protein (BMP)-4 [61,62], among other factors.

Cardioprotection & myocardial regeneration

Improvements in myocardial function following stem cell transplantation have traditionally been attributed to stem cell differentiation to the cardiomyocyte lineage within host myocardium. However, in the last decade it has been demonstrated that few, if any, exogenous stem cells actually engraft and differentiate [63–66] and that perceived cardiomyocyte differentiation may be a result of fusion of transplanted stem cells with host myocardial cells [67,68]. Thus, researchers have sought alternative explanations for observed functional improvements. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that BM-MSCs secrete cytoprotective molecules that reduce apoptosis and necrosis in cardiomyocytes and other myocardial cell populations [69–73]. ESC transplantation into infarcted myocardium also attenuates cell apoptosis, hypertrophy and fibrosis via ESC-secreted autocrine and paracrine factors [74]. Cardioprotective molecules secreted by stem cells include bFGF, VEGF, PDGF, IL-1β, IL-10, stem cell-derived factor (SDF)-1, HGF, IGF-1, thymosin-β4 and Wnt5a [69–71,75–78].

The functional benefits of stem cell transplantation have been attributed to several other mechanisms in addition to cardioprotection. Secretion of bioactive molecules such as bFGF, HGF, angiopoietin-1 and -2 (Ang-1 and -2), VEGF and cysteine-rich protein 61 by BM-MSCs and ASCs leads to increased vascular density and blood flow in ischemic myocardium, resulting in increased perfusion and function [5,79,80]. In addition, cardiac levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, factors implicated in angiogenesis, were shown to be elevated following BM-MSC transplantation [81]. The expression of SDF-1, IGF-1, HGF and PEDF are known to promote repair and regeneration by facilitating circulating progenitor cell recruitment to injured tissues [4,82–84]. In addition, secretion of HGF and IGF-1 is essential for activation of cardiac stem cells, which may contribute to endogenous repair mechanisms [85]. Stem cell transplantation may also attenuate left ventricular chamber dilation postmyocardial infarction (MI) via the secretion of collagens, TGF-β, MMPs, TIMPs, serine proteases and serine protease inhibitors, which act to re-establish ECM homeostasis and inhibit cardiac fibrosis [86]. BM-MSCs in vitro express a number of molecules implicated in ECM synthesis and remodeling (e.g., collagen I and III, MMPs and TIMPs) and inhibit cardiac fibroblast proliferation and collagen synthesis [87,88]. Furthermore, levels of MMP-2 and -9, which are significantly increased in hearts with dilated cardiomyopathy, are limited to normal levels in hearts treated with BM-MSCs and less collagen deposition is found than in untreated hearts [89]. It has also been noted that expression of several of these molecules is enhanced under hypoxic conditions [75,76,90]. Taken together, these results suggest that stem cells may be potent mediators of ECM remodeling post-MI.

Skeletal myoblasts are myogenic progenitor cells with the ability to expand and form new fibers following muscle injury, and therefore have also been investigated as a potential cell source for post-MI myocardial repair. SkMbs in vitro express a number of anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl-2 and BAG-1) and genes associated with ECM remodeling (MMP-2, -7 and -9), and a number of growth factors implicated in angiogenesis, proteases involved in matrix remodeling and cytokines involved in apoptosis are secreted by skMbs cultured in vitro under normoxic and hypoxic conditions [63]. While several clinical trials have demonstrated improved left ventricular functional outcomes in patients treated with skMbs [91–93], the clinical benefit of skMb transplantation in heart failure is questionable at this time [94].

Wound healing

Optimal wound healing requires a complex series of biological events such as cell migration, proliferation, ECM remodeling and angiogenesis [95]. In addition, the impairment of cytokine production by inflammatory cells is crucial to wound healing [95–97]. Therefore, stem and progenitor cell secretion of the factors mentioned in previous sections of this review (those implicated in immunoregulation, cell proliferation and migration, neovascularization, and ECM synthesis and remodeling), may accelerate wound healing when administered to the site of injury. Studies on BM-MSC, ASC and amnion-derived progenitor cell administration to dermal wounds have demonstrated such acceleration [7,98–101]. In addition to their previously discussed immunosuppressive properties, BM-MSCs and ASCs administered to chronic wounds enhanced capillary density, but without engraftment in vascular structures. Upon closer examination, it was determined that BM-MSCs induced neovascularization through secretion of the pro-angiogenic factors Ang-1 and VEGF within the wound beds [95]. ASCs implanted into chronic dermal wounds enhanced granulation tissue thickness, epithelialization and capillary formation by secreting angiogenic cytokines such as bFGF, PDGF, VEGF and HGF [99,100]. Human amniotic progenitor cells have been shown to inhibit neutrophil and macrophage migration to the site of injury through the secretion of migration inhibitory factor and the suppression of IL-1α and -1β. Amniotic progenitor cells also release several anti-inflammatory factors that prevent apoptosis and enhance wound healing [8]. While the paracrine actions of stem and progenitor cells are now known to play a role in wound healing, the entirety of biomolecule production by various progenitor cell populations and their role in wound healing has yet to be thoroughly characterized.

Osteogenic regeneration

Fetal endochondral bone healing has been demonstrated to be a scar-free process. The difference in the bone-forming ability of children and adults has in part been attributed to differential expression of several growth factors such as TGF-β1, TGF- β3 and bFGF. Microarray analysis of calvarial regenerates from juvenile and adult mice demonstrated a marked increase of pro-osteogenic cytokines (e.g., BMP-2, -4 and -7, bFGF and IGF-2) in juvenile samples. In addition, increased levels of bone-related ECM proteins, such as procollagens Col6a1, Col3a1 and Col4a1, as well as MMP-2 and -14, pleiotrophin and cathepsin K, were found in juvenile regenerates compared with adults [102]. Given the aforementioned secretion profiles of certain stem and progenitor cell populations in vitro and in vivo, it follows that these cells may provide a cell source capable of modulating bone regeneration through paracrine actions, and genetically modified stem and progenitor cells have been used to this end [103].

While preliminary results using stem and progenitor cells to regenerate tissues following disease or traumatic injury are promising, the efficacy of stem/progenitor cell transplantation is still under debate, and further characterization of the various stem and progenitor cell populations and subpopulations and their secretion profiles, differentiation potential and ability to release growth factors in adequate amounts to produce functional benefits in patients is needed. Further methods to modulate the paracrine actions of stem and progenitor cells and to harness biomolecules produced by these cells are currently under investigation.

Stem cell paracrine actions & cancer

Cancers are characterized by aberrant growth processes and can occur in response to tissue damage. While stem cells are normally necessary for the repair of injured tissues, it has been speculated that they may enable tumor formation, growth and maintenance. A critical factor in tumor formation and growth is the microenvironment consisting of a number of cell types (including fibroblasts, endothelial cells and recruited inflammatory cells), the ECM and local, soluble molecules [104]. Tumor-supportive cells release growth factors, cytokines and chemokines that provide trophic support to the tumor by providing not only nutrients, but also an adequate blood supply [105–107]. Following intravenous administration in animal models, stem and progenitor cells have been shown to selectively home to the site of a tumor and to replenish the cancer-associated stroma [108–111]. Stem cell tumor tropism exists in response to tumor cell secretion of growth factors, cytokines and ECM molecules, such as PDGF, VEGF, EGF, IL-6 and -8, MMP-1 and SDF-1, and inhibition of these factors leads to loss of such tropism [108,109,111]. Given their secretion of angiogenic and proinflammatory molecules, such as VEGF and IL-6 and matrix-degrading enzymes such as MMPs, it has been hypothesized that certain stem cell populations may promote rather than impede tumor growth and migration [112,113].

To date, conflicting reports have emerged demonstrating increased, decreased and unchanged in vitro and in vivo tumor cell proliferation in the presence of human BM-MSCs or BM-MSC soluble factors [46,114–116]. It has been postulated that stem cell effects on tumor cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo could be a result of several mechanisms. Crosstalk between stem cells and malignant cells could result not only in increased tumor cell proliferation, but also in a stem cell phenotypic change to cells that support neoplastic cell growth [115]. Downregulation of tumor-suppressive immune responses as a result of anti-inflammatory molecule secretion by stem cells could also enable tumor growth [117]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that stem cell expression of MMPs and the chemokine CCL5 (RANTES) can facilitate tumor motility and metastasis [118]. Subpopulations of BM-MSCs in vitro expressing MMP1 exhibited increased tumor tropism when compared with subpopulations that did not express MMP1 [108]. Conversely, tumor growth may be impeded through cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of tumor cells in response to stem cell transplantation [46,119].

The confounding results of these studies have been attributed to the differences and heterogeneity of tumor and stem cell populations. Determination of the specific interactions between tumor cells and stem cells in different types of cancer could yield insights into possible novel stem cell therapies to combat cancer, and the complex relationship between stem cells and tumor formation, maintenance and growth is discussed in greater detail elsewhere [120–127]. Given these conflicting results, and the potential for stem cells to accelerate tumor growth and metastasis, stem cell treatments for various cancers have been approached with much caution thus far. However, given their tumor tropism, MSCs are being investigated as potential tumor-targeting cells that could have utility as localized delivery vehicles for anticarcinogenic agents to tumors.

Modulating stem cell paracrine actions

Since the realization that the beneficial effects of stem cell transplantation may be due to the localized release of a number of trophic factors, and not attributed (in part or entirely) to stem cell differentiation, many scientists have focused on modulating the paracrine actions of stem cells to enhance therapeutic efficacy. A number of different approaches, primarily focused on genetic manipulation and in vitro preconditioning, have been examined to increase stem cell survival upon transplantation (thereby increasing the total amount of secreted trophic factors and prolonging the duration of secretion) and to directly enhance biomolecule production in order to effect greater functional benefit with stem cell transplantation for tissue regeneration.

Genetic manipulation of stem cells

Stem and progenitor cells have been genetically engineered with a number of transgenes to more effectively engraft in hostile environments and to secrete increased amounts of trophic factors. A number of approaches to genetically modify stem cells have been utilized, including viral and nonviral delivery of plasmids and switches for conditional gene expression in order to determine the most efficient route of gene delivery and subsequent expression for each cell population and application for tissue regeneration [128,129].

Engineered stem cells for improved graft survival

In a majority of cases where stem cells are transplanted into injured tissues, they are introduced into a hostile, ischemic environment. Thus, many transplanted cells do not survive and undergo apoptosis, thereby limiting their paracrine actions. In order to increase graft survival, BM-MSCs have been modified with anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2, Akt and HO-1. BM-MSC overexpression of Bcl-2 has been shown to increase MSC VEGF secretion (and resultant capillary density) under hypoxic conditions in vivo and decrease apoptosis of BM-MSCs in vitro and in vivo [130]. Akt-modified BM-MSCs have been shown to be resistant to apoptosis through secretion of a number of molecules such as VEGF, IGF-1, bFGF and HGF, and it has been demonstrated that secretion of these molecules is increased under hypoxic conditions [66,75,76]. Finally, HO-1-expressing MSCs demonstrate enhanced tolerance for hypoxia–reoxygenation in vitro and are protected from apoptosis and inflammatory injury in vivo [131].

Engineered stem cells for neural regeneration

For more efficient neural regeneration, genetically modified cells overexpressing neuroprotective factors or neurotransmitters have been investigated. NPCs and NSCs were virally transduced with a neurotrophic factor, NT-3, BDNF or GDNF, and genetically modified cells survived for extended periods of time upon transplantation and improved functional outcomes via secretion of neurotrophic factors [132–135]. BM-MSCs modified to overexpress BDNF were significantly more effective in eliciting functional recovery from ischemia and decreasing the number of apoptotic cells in the infarct zone in a rat stroke model when compared with unmodified BM-MSCs [136,137]. Genetically engineered rat and human BM-MSCs also produced increased amounts of dopamine in vitro and in vivo, thereby providing a potential treatment for patients suffering from PD [128,138]. Furthermore, NPCs derived from mouse ESCs modified with a disruption of the ADK gene released adenosine in vitro and in vivo. ESC-derived NPCs that released adenosine demonstrated increased survival when transplanted in vivo. More strikingly, mice and rats receiving ADK-modified ESC-derived NPCs demonstrated a marked inhibition in seizure activity, thereby suggesting the utility of these cells as an antiepilepsy treatment [139–141]. Human BM-MSCs have also been genetically modified to produce adenosine and used to suppress seizures in mice [140,142]. Mouse ESCs have also been genetically modified to overproduce γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in a controllable manner in order to suppress seizures [143]. These studies demonstrate that stem and progenitor cells can be genetically modified in order to produce factors implicated in neurodegenerative diseases.

Engineered stem cells for myocardial regeneration

Ischemic myocardium is a difficult milieu for cell engraftment and survival due to lack of oxygen and nutrients, dysfunctional mechanical forces and altered biochemical environments [144]. Research focusing on the use of cells as carriers for genes implicated in angiogenesis and myogenesis has emerged to increase the efficiency of cell transplantation. A variety of cell types, including skMbs, muscle-derived stem cells (MDSCs) and BM-MSCs, have been investigated as carriers of exogenous genes [145]. Cells have been modified to overexpress VEGF, HGF, myogenic determination gene MyoD, SDF-1α and Ang-1 for preclinical studies for myocardial repair following MI. Preliminary results from these studies show increased commitment of cells to the myogenic lineage, increased cell engraftment and increased angiogenesis in the ischemic region [84,146–154]. Studies evaluating numerous other angiogenic and myogenic genes, including other VEGF isoforms, PDGF and TGF-β1, have also been suggested for increasing the efficiency of cell therapy [145]. It has been demonstrated that Akt-modified BM-MSCs exert enhanced cardioprotective and inotropic effects on ischemic cardiomyocytes both in vitro and in vivo through the enhanced secretion of molecules such as VEGF, IGF-1, secreted frizzled-related protein 2, bFGF and HGF [66,75,76,155]. Transplantation of Akt-modified BM-MSCs into infarcted myocardium has also been shown to maintain normal metabolism in surviving myocardium for up to 2 weeks post-MI, an effect that was absent when unmodified BM-MSCs were administered, and this effect has been attributed at least in part to the paracrine actions of the modified MSCs [156]. In addition, Bcl-2-modified BM-MSCs have been shown to increase capillary density by secreting VEGF, thereby augmenting functional recovery in ischemic myocardium [130].

Engineered stem cells for osteogenic regeneration

Stem and progenitor cells have been modified with a number of genes for growth factors known to stimulate mineralization and enhance endochondral bone formation. A number of studies on enhanced bone repair with genetically modified cells have been conducted to date. Researchers have demonstrated that genetic modification of BM-MSCs, peripheral blood-derived cells, skMbs, MDSCs and ASCs to overexpress a number of BMPs (e.g., BMP-2, -4, -7 and -9), LIM mineralization protein-1 and IGF-1 have proven successful in the use of these cells to repair critical size bone defects [157–159]. In addition, MDSCs modified to overexpress both VEGF and BMP-4 resulted in enhanced BM-MSC recruitment, cell survival and endochondral cartilage formation when compared with unmodified cells and cells overexpressing VEGF alone. These results not only demonstrated a synergistic effect between VEGF and BMP-4 in bone repair, but also provided insight into VEGF’s role as a potent mediator of the osteoinductive signal provided by BMP-4 [157]. It has been noted that transduction of BM-MSCs with BMP-2 not only accelerates bone formation and regeneration, but also increases angiogenesis in the injured tissue [157].

Engineered stem cells for the treatment of cancer

Given their tropism for tumors, MSCs and ASCs can serve as a ‘Trojan horse’ for delivering anticancer genes, proteins and drugs to tumor cells. The gene IFN-β has been shown to exert antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on tumor cells in vivo; however, the amounts of IFN-β necessary for tumor inhibition via systemic administration is greater than that which can be tolerated by humans, and therefore, clinical trials for IFN-β therapy have failed [160]. In lieu of IFN-β systemic administration, researchers have transduced stem cells with the IFN-β gene. Intravenous administration of IFN-β-expressing NPCs and BM-MSCs in tumor-bearing mice resulted in stem cell incorporation into tumors and subsequent inhibition of tumor growth and angiogenesis [160–162]. BM-MSCs expressing a truncated VEGF receptor (tsFlk-1) also inhibited tumor growth in a mouse model of lymphoma [163]. While B16 (murine melanoma) cell injection into mice was demonstrated to result in tumor formation only with BM-MSC coinjection (thereby confirming the role of MSC immunosuppression in tumor formation), it has since been demonstrated that genetically modified BM-MSCs expressing IL-2 significantly delay B16 tumor growth [164]. In addition, ASCs and BM-MSCs transduced with the cytosine deaminase gene have been shown to possess the ability to home to tumors and exert potent antitumor effects by converting a coinjected prodrug into its toxic form via expression of the cytosine deaminase gene [165–167].

While genetic manipulation of stem cells increases cell survival in hostile host environments, enhances secretion of proteins that may aid functional recovery following injury and suppresses tumors, there are many questions that remain to be answered before clinical application of genetically modified cells can be considered feasible. For instance: What is the optimal method for genetic modification? What is the optimal stem cell source for each given application? What are the unexpected and possibly unwanted effects following transplantation of these cells? How long will these cells engraft and survive in the host and maintain their therapeutic potential? Are these cells immune privileged? Until such questions can be answered, human clinical trials with genetically modified stem cells will be approached cautiously.

Preconditioning stem cells

Preconditioning stem cells (i.e., intentionally exposing them to a controlled amount of stimulus for a defined period of time in order to produce a desired response) may have utility in enhancing cell secretion of trophic factors. In contrast to genetic engineering, which modifies a single target gene, preconditioning can be used to elicit a more global and complex cell response to a single stimulus. Some responses are due to known mechanistic relationships (as with hypoxia and angiogenic factor production), while the basis of some responses remain unknown to date (as with mechanical stimulation). A number of primary, stem and progenitor cells have been subjected to preconditioning regimens to increase production of desired trophic factors, thereby augmenting cell paracrine actions.

Hypoxic exposure

In vitro pretreatment with hypoxic or anoxic exposure (<5% O2) can enhance the paracrine actions of BM-MSCs through the induction of HIF-1α, a transcription factor, which binds to the hypoxia response elements in a number of target genes, including several angiogenic growth factors [111,168]. (It should be noted that hypoxic in vitro environments often mimic physiologic oxygen concentrations. Therefore, ‘hypoxic’ exposure is actually something of a misnomer and relative to normoxic atmospheric conditions = 21% O2.) While temporary exposure to hypoxia had no effect on cell survival in some studies, it did increase the expression of several growth factors such as VEGF, bFGF, IGF-1, thymosin-β4 and HGF [76,130], factors known to play a role in cell recruitment, apoptosis and angiogenesis. Hypoxic preconditioning also increased the in vitro expression of several anti-apoptotic genes such as Akt and eNOS [66,70]. Furthermore, BM-MSCs exposed to anoxic preconditioning were shown to exert enhanced cytoprotective effects on cardiomyocytes (compared with unconditioned BM-MSCs) when transplanted into infarcted myocardium [169]. Therefore, hypoxic pretreatment may lead to increased donor and host cell survival in ischemic environments and enhanced stem cell paracrine actions, thereby providing functional benefits to the host.

Thermal shock induction

Heat-shock protein (Hsp) production, as the name implies, can be induced by transiently exposing cells to increased temperatures (typically 39–45°C). The family of Hsp molecules possesses cytoprotective properties through the negative regulation of Fas-mediated apoptosis and prevention of proinflammatory cytokine production [170–172]. It has been demonstrated that thermal shock induced via exposure of primary cardiomyocytes to hyperthermic conditions (39°C) resulted in increased expression of Hsp70, thereby protecting these cells from subsequent oxidant stress in vitro and in vivo [172,173]. Exposing human dental pulp stem cells to hyperthermic conditions (38–45°C) enhanced the production of the inflammatory modulator leukotriene B4 in conditioned cells compared with unconditioned controls [174]. However, characterization of enhanced trophic factor production by various stem cell populations upon exposure to thermal shock has yet to be rigorously examined. Given the role of Hsp molecules in cytoprotection and immune modulation, thermal shock preconditioning of stem and progenitor cells could prove to be a useful and simple means of augmenting paracrine actions.

Pharmacologic treatment

Pharmacologic preconditioning of a number of stem and progenitor cell populations in order to enhance graft survival and trophic factor secretion has also been investigated. SkMbs and BM-MSCs treated with diazoxide, a potassium channel activator, demonstrated increased cell survival upon transplantation into an ischemic environment. Enhanced Akt phosphorylation, cyclooxygenase-2 and IL-11 expression levels in skMbs were postulated to play a role in autocrine cell survival signaling mechanisms [175,176]. Increased secretion of Ang-1, VEGF, HGF and bFGF by preconditioned skMbs was postulated to increase angiomyogenesis through paracrine actions once transplanted [177]. While enhanced Akt phosphorylation was also evident with diazoxide-treated BM-MSCs, the mechanism of cell survival was demonstrably different for these cells when compared with skMbs [175,176]. Treatment of BM-MSCs with trimetazidine (1-[2,3,4-trimethoxybenzyl] piperazine), a widely used anti-ischemic drug for treating angina in cardiac patients, increased cell viability in response to H2O2 exposure [178]. In addition, treatment of rat BM-MSCs with β-mercaptoethanol upregulated Hsp72 expression resulting in increased resistance to oxidant stress [179] and providing a potential means for regulating host inflammatory response. Therefore, pharmalogic preconditioning of stem and progenitor cells in vitro may increase cell survival, thereby enhancing their paracrine actions in hostile environments.

Proinflammatory cytokine exposure

Since proinflammatory cytokines are necessary for the activation of certain stem cell populations, it has been postulated that preconditioning stem and progenitor cells with these cytokines could augment paracrine modulation of the host immune response. It has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo that MSCs suppress T-cells and alleviate the effects of GvHD only when IFN-γ is present in sufficient levels for MSC activation [32,37]. Furthermore, MSCs respond to IFN-γ in a dose-dependent manner in vivo, with increased doses of IFN-γ being more efficient at eliciting MSC immunosuppression [37]. More recently, it has been established that the addition of TNF-α could enhance MSC immunosuppression activated by IFN-γ [15,32]. Since IFN-γ provides the necessary stimulus for MSC immunosuppressive activity in vivo, it can be reasoned that preconditioning MSCs with IFN-γ, and possibly with TNF-α, in vitro prior to cell transplantation may provide a potential strategy for activating and increasing MSC immunosuppressive transplantation. Cytokine preconditioning methodologies may also work for other stem and progenitor cell populations and could have utility in modulating host immune response through enhanced paracrine actions.

Biophysical preconditioning

Recent reports on cell exposure to biophysical stimuli provide potential alternatives for boosting stem cell paracrine actions. The Holmium:YAG laser is extensively used in orthopedic surgeries, and efforts to characterize the effects of the laser on cell viability yielded intriguing results; shock waves and thermal shock caused by the laser-induced cell expression of Hsp70 [180]. As the Hsp family of molecules has been implicated in cytoprotection and immune modulation, laser preconditioning of stem and progenitor cells could provide a means of increasing their paracrine actions. In addition, while many published reports exist on in vitro stem cell differentiation in response to imposed mechanical strain, a number of these studies also report that imposed mechanical strain can modulate ECM synthesis, deposition and mineralization [181–184]. Given the robust role of ECM molecules in tissue repair and regeneration, it follows that mechanical conditioning may enhance stem and progenitor cell ECM molecule production, thereby augmenting their paracrine actions.

Harnessing stem cell paracrine factors

While cell therapies using stem and progenitor cells to treat traumatic injury or disease have yielded some promising preliminary results, a number of hurdles remain for the clinical implementation of regenerative cell therapies. One concern regarding the development of therapies from pluripotent stem cell sources is the potential for the cells to form teratomas in vivo [185–187]. On the other hand, the use of multipotent and lineage-restricted stem and progenitor cells, although potentially safer, is limited by their restricted plasticity and senescence when expanded in vitro. Finally, cell sourcing issues concerning obtaining adequate cell numbers and immune compatibility often reduce their potential for clinical use. Thus, many researchers have begun to consider alternatives to cell transplantation that rely upon harnessing and delivering the trophic factors produced by stem cells to stimulate tissue repair and regeneration.

Stem cell soluble factors

It has been postulated that the beneficial effects of stem cells are not dependent on cell–cell contacts, but that soluble trophic factors secreted by stem cells can exert potent paracrine effects on other cell types. This initially overlooked fact has now been demonstrated by a number of studies utilizing conditioned media, collected from a variety of stem cell populations, to exert beneficial effects on cells and tissues in vitro and in vivo.

The treatment of diabetic mice with BM-MSC-conditioned media resulted in lowered blood glucose levels at baseline and after a glucose load and protected pancreatic cells from apoptosis compared with controls, thereby demonstrating that the beneficial effects of MSC transplantation in a diabetic mouse may be due to the paracrine actions of MSC-secreted factors on injured pancreatic cells [188]. The presence of relatively high levels of anti-apoptotic and angiogenic factors in BM-MSC-conditioned media was confirmed using ELISAs. The transfer of BM-MSC-conditioned media to neonatal rat cardiomyocytes in vitro resulted in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by increasing total protein content, cell area, [3H]-leucine incorporation, and ANF gene expression [189]. It was concluded that the beneficial effect of BM-MSC transplantation into ischemic myocardium may therefore be attributed (at least in part) to the paracrine effects of MSCs on host cardiomyocytes.

Treatment with ASC-conditioned media blocked neuronal damage, tissue loss and functional impairment in a rat neonatal model of hypoxic–ischemic injury-induced encephalopathy [190]. Long-term, lasting beneficial effects on spatial learning and memory deficiency were observed in rats receiving conditioned media when compared with controls. ASC-conditioned media significantly decreased caspase-dependent cell death and exerted neuroprotective effects on host cells and tissues. It was concluded that relatively high levels of neuroprotective and anti-apoptotic factors in conditioned media, such as IGF-1 and BDNF, rescued neonatal brains injured by hypoxic–ischemic injury. The in vitro treatment of ovarian cancer cells with conditioned media from heat-shocked ASCs and amniotic fluid-derived stem cells resulted in decreased tumor cell viability compared with controls by inducing greater nuclear condensation and growth cycle arrest of tumor cells [191]. Cytokine arrays of conditioned media demonstrated that the effects on tumor cells were mediated by stem cell secretion of trophic factors such as angiogenin, IGF-binding protein 4, NT-3 and chemokine ligand 18.

Similar to other stem cell populations, the proliferative activity and differentiation potential of periodontal ligament-derived stem cells (PDLSCs) decrease with age. However, treatment of aged PDLSCs with conditioned media from young PDLSCs significantly increased proliferation and differentiation potential in vitro and in vivo. Conversely, the differentiation potential of young PDLSCs was decreased following treatment with conditioned media from aged PDLSCs. Taken together, these data suggest that conditioned media from young PDLSCs contain soluble growth factors and differentiation factors (e.g., IGF-1, PDGF, IL-1, TGF-β, BMP-2 and BMP-4) that may exert potent effects on aged stem cells in vitro and in vivo [192].

Finally, conditioned media from human ESC-MSCs exerted a cardioprotective effect and preserved cardiac function in a porcine MI model [193]. Cardioprotection by ESC-MSCs is conferred through enhancing cell viability in the presence of oxidative stress and by decreasing apoptosis via the TGF-β signaling pathway. It was further ascertained that cardioprotection by ESC-MSC-conditioned medium was mediated by large complexes (>1000 kDa) that may include a number of proteins and lipids. However, the exact molecules mediating the beneficial effects of these cells remain to be elucidated.

While the aforementioned studies highlight several recent studies on the potent paracrine effects of stem cell-conditioned media, many such studies exist demonstrating the potential of stem cell-conditioned media for therapeutic application in lieu of cell transplantation. In addition to providing alternative stem cell therapies, conditioned media studies also help elucidate the mechanisms behind stem cell paracrine actions, thereby providing valuable insights into the biology and therapeutic application of these cells. Recent reports on methods to isolate and concentrate stem cell-conditioned media elucidate experimental protocols for harnessing the trophic factors produced by stem cells [194]. However, certain limitations exist to the therapeutic use of stem cell-conditioned media and include concerns on contamination by animal products, the in vitro half lives of molecules secreted by stem cells, and the relative amounts of secreted factors and the effective dosage necessary to elicit a functional response in vivo.

Stem cell extracellular matrices

The ECM is widely known to be composed of structural and functional elements responsible for maintaining normal tissue homeostasis and dynamically responding to tissue injury. Collagens, laminins and fibronectin are fibrillar molecules present in most basement membranes, and several isoforms of collagens and laminins have been documented [195–201]. Growth factors such as FGF, HGF, PDGF, VEGF and IGF can also be stably retained within the ECM by binding directly to ECM proteins or glycosylaminoglycans [202,203]. Potent morphogenic molecules such as WNTs and BMPs, as well as their antagonists, can also be found in the ECM [204,205].

Given possible limitations with cell sourcing and the therapeutic administration of conditioned media, it has been postulated that successful isolation of ECM from cells and tissues may provide an alternative approach to deliver potent reservoirs of morphogenic biomolecules. Decellularized tissues lack viable cells but retain natural ECM components from the tissue of origin [206–209], and such acellular biomaterials have been extracted from various tissue sources including small intestinal submucosa, skin, bladder, human placenta, liver, heart and blood vessels [210–221]. Studies have suggested that transplantation of acellular matrices from somatic tissues can lead to repair and/or regeneration in milieus where normal, homeostatic tissues cannot recapitulate the complex signaling environment directing morphogenic processes during tissue development or regeneration [222–224]. Furthermore, acellular biomaterials are less likely than other materials to elicit an inflammatory response when transplanted (due to conservation of ECM across species), and successful use of these materials has been demonstrated in soft and hard tissue repair, ranging from heart valves and nerve grafts to osteoinduction.

Recent studies have demonstrated successful isolation of acellular matrices from not only tissues, but also somatic cells in culture. Human foreskin fibroblast ECM was chemically isolated and used alone and in combination with poly(ε-caprolactone) in vitro. Hybrid ECM–poly(ε-caprolactone) electrospun scaffolds exhibited excellent biomechanical properties and supported the attachment and proliferation of human ASCs throughout the constructs [225]. Human dermal fibroblasts were demonstrated to produce ECM in a dose-dependent manner when treated with EGF [226]. In addition, ECM was mechanically isolated from cultured porcine chondrocytes and was demonstrated to more effectively direct ECM deposition by rabbit chondrocytes and production of high-quality cartilage in vitro when compared with a polyglygolic acid control scaffold [227]. While the aforementioned studies demonstrate successful isolation of ECM from somatic cells in vitro and the ability to seed a secondary cell type onto the acellular matrices, they do not characterize the effects of the ECM on cell behavior or the paracrine actions of the ECM in vitro and in vivo. Such studies would do much to explore the role of ECM insoluble factors on tissue regeneration.

To date, few studies on the isolation of acellular matrices from stem and progenitor cell populations currently exist. Considering the potent paracrine actions of stem cells, it follows that stem cell-derived acellular matrices may harbor a variety of trophic molecules. Murine BM-MSC ECM was shown to be composed of collagens I, III and IV, syndecan-1, perlecan, fibronectin, laminin, biglycan and decorin (similar to native bone marrow ECM). BM-MSC ECM preserved the colony-forming potential of murine MSCs in vitro compared with other tissue culture substrates and decreased the spontaneous osteogenic differentiation of MSCs seeded onto the ECM. Upon transplantation into immuno-compromised mice, murine MSCs seeded onto BM-MSC ECM generated five times as much bone and eight times as much hematopoietic marrow compared with MSCs cultured on tissue culture plastic [228]. It has been hypothesized that the enhanced performance of MSCs is due to BM-MSC-secreted proteins harbored within the ECM. Titanium scaffolds seeded with rat MSCs, cultured with osteogenic supplements, and subsequently decellularized were demonstrated to promote matrix mineralization by BM-MSCs even in the absence of osteogenic factors [229]. In addition, acellular ECM constructs promoted angiogenesis (but not osteogenesis) in vivo when applied in an intramuscular osteoinduction model where normal tissues are generally incapable of adequate neovascularization [230]. These results further demonstrate that BM-MSC-derived ECM contains a complex assortment of factors capable of directing the behavior of exogenous cell populations.

BM-MSC-derived ECM has also been shown to be neurosupportive. BM-MSCs were chemically decellularized, as were BM-MSCs stably transfected to express the Notch 1 intracellular domain protein. The neurosupportive effects of both MSC populations were determined to be due to ECM factors and not due to soluble factors or the cells themselves [231]. In addition, the fact that ECM produced by Notch 1 transfected MSCs was better at promoting neural cell growth compared with ECM from unmodified MSCs was attributed to enhanced expression of collagens, laminins, MMPs, TIMPs, tenascin and fibulin by transfected cells. Therefore, BM-MSC-derived ECM could be a potent mediator of neuroregeneration in vivo, and genetic modification of BM-MSCs could further enhance these ECM properties.

Recently, acellular matrices derived from ESCs (in the form of differentiating spheres called embryoid bodies) have been successfully isolated using chemical and physical decellularization methods [232–234]. Decellularization treatments inhibited cell viability while retaining ECM components such as collagen IV, laminin, fibronectin and hyaluronan [233]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that acellular matrices can be seeded with exogenous cells and maintained in vitro [234]. These cumulative data suggest that the exogenous administration of an acellular matrix derived from stem cells may catalyze tissue repair and regeneration through paracrine actions of molecules sequestered within the matrix. Furthermore, acellular matrices from various stem cell populations may differentially modulate tissue regeneration based on the potential (i.e., maturity), genetic modification and/or preconditioning of the stem cells prior to decellularization.

Future perspective

While stem cell therapies for tissue regeneration have been conventionally driven by stem cell differentiation for the replacement of damaged tissues, recent advances in the field have characterized the paracrine actions of these cells. It has been demonstrated that in many instances, the functional benefits of stem cells are due in large part to the variety of growth factors, chemokines, cytokines and immunosuppressive molecules secreted by these cells at the site of injury. Consequently, the intentional use of stem cells to modify tissue microenvironments is likely to become a focus of stem cell research in the near future. Regardless of differentiation to specific phenotypes, researchers may find that application of a variety of stem cell populations, in unlikely tissue environments, yields previously unanticipated, yet effective, results for tissue regeneration. For instance, transplantation of NPCs to ischemic myocardium may result in decreased cardiomyocyte apoptosis, increased neovascularization and increased recovery from ischemia as a result of neurotrophic and angiogenic factor secretion by these cells. In addition, optimal genetic engineering and preconditioning regimens of cells to augment trophic factor secretion for an intended application will become more widely investigated and characterized, leading to more effective and well-characterized mechanisms of paracrine action.

The application of stem cell-derived biomolecules for tissue regeneration may provide alternative, stem cell-derived therapies that overcome current cell sourcing issues. Stem cell-secreted soluble factors, from a variety of stem cell populations and in response to external stimuli, will be better characterized via proteomic analyses and more targeted to specific tissues in years to come. Acellular biomaterials derived from a number of stem cell populations under a variety of genetic modifications and preconditioning regimes will become more common. Hybrid biomaterials consisting of synthetic polymers and stem cell-derived matrices and/or secreted soluble factors will also be developed for a number of soft and hard tissue regeneration applications. Tumor-targeting therapies using stem cell-derived molecules, acellular matrices and hybrid biomaterials will also become more sophisticated in terms of stem cell use for the targeted delivery of antitumorigenic agents in the years to come. In conclusion, understanding the paracrine actions of stem cell populations and learning to modulate and harness them provides researchers with a myriad of treatment options for traumatic injury and disease that have so far been limited by cell sourcing issues. The forthcoming advances in defining and applying paracrine actions will significantly benefit the regenerative medicine applications of stem cells in the coming years.

Executive summary

Stem cell paracrine actions

A recent paradigm shift has suggested that the beneficial effects of stem cells may be due to paracrine actions and not just differentiation.

Stem cells secrete a broad spectrum of cytokines, chemokines and growth factors implicated in a number of biological phenomena.

Stem cell modulation of physiological responses

Stem cells modulate the immune response alone and when co-transplanted with other cell types.

Stem cells protect host cells and can attenuate graft-versus-host disease and autoimmune diseases via immunosuppression.

Stem cells secrete numerous trophic factors that have been implicated in neural, myocardial and osteogenic regeneration, as well as in wound healing.

Conflicting reports on stem cell paracrine effects on tumor growth, suppression and metastasis have emerged.

Manipulating stem cell paracrine actions

Stem cells have been genetically engineered to overexpress a number of genes implicated in graft survival and tissue regeneration.

Stem cells have also been genetically modified to overexpress and secrete antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic genes for tumor suppression.

Methods to precondition stem cells through exposure to hypoxia, pharmacologic agents, thermal shock and proinflammatory cytokines have proven successful in enhancing post-transplantation survival and paracrine actions of these cells.

A cellular stem cell paracrine approaches

Methods to harness stem cell paracrine factors for therapeutic application, independent of the cells themselves, circumvent issues surrounding cell transplantation.

Soluble trophic factors produced by stem cells in vitro can exert potent paracrine effects on other cell types in vitro and in vivo.

Stem cell-derived acellular matrices harboring morphogenic factors may catalyze tissue repair and regeneration when transplanted in vivo.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

PR Baraniak is funded by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the American Heart Association. TC McDevitt is funded by grants from the NIH (EB007316) and the Georgia Tech–Emory Collaboration for Regenerative Medicine and Engineering. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

- 1.Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilroy GE, Foster SJ, Wu X, et al. Cytokine profile of human adipose-derived stem cells: expression of angiogenic, hematopoietic, and proinflammatory factors. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007;212(3):702–709. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan AI. Why are MSCs therapeutic? New data: new insight. J. Pathol. 2009;217(2):318–324. doi: 10.1002/path.2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarojini H, Estrada R, Lu H, et al. PEDF from mouse mesenchymal stem cell secretome attracts fibroblasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;104(5):1793–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schinkothe T, Bloch W, Schmidt A. In vitro secreting profile of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17(1):199–206. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu CH, Hwang SM. Cytokine interactions in mesenchymal stem cells from cord blood. Cytokine. 2005;32(6):270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu X, Li H. Mesenchymal stem cells and skin wound repair and regeneration: possibilities and questions. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335(2):317–321. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0724-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilancheran S, Moodley Y, Manuelpillai U. Human fetal membranes: a source of stem cells for tissue regeneration and repair? Placenta. 2009;30(1):2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trivedi P, Hematti P. Derivation and immunological characterization of mesenchymal stromal cells from human embryonic stem cells. Exp. Hematol. 2008;36(3):350–359. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W. Mesenchymal stem cells in cancer: friends or foes. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7(2):252–254. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.2.5580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bochev I, Elmadjian G, Kyurkchiev D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow or adipose tissue differently modulate mitogen-stimulated B-cell immunoglobulin production in vitro. Cell Biol. Int. 2008;32(4):384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen BL, Chang CJ, Chen YC, Hu H-I, Bai C-H, Yen M-L. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal progenitors possess strong immunosuppressive effects toward natural killer cells as well as T lymphocytes. Stem Cells. 2009;27:451–456. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bartholomew A, Sturgeon C, Siatskas M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30(1):42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00769-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nasef A, Chapel A, Mazurier C, et al. Identification of IL-10 and TGF-β transcripts involved in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation during cell contact with human mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Exp. 2007;13(4–5):217–226. doi: 10.3727/000000006780666957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.English K, Barry FP, Field-Corbett CP, Mahon BP. IFN-γ and TNF-α differentially regulate immunomodulation by murine mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol. Lett. 2007;110(2):91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sato K, Ozaki K, Oh I, et al. Nitric oxide plays a critical role in suppression of T cell proliferation by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood. 2007;109(1):228–234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meisel R, Zibert A, Laryea M, Gobel U, Daubener W, Dilloo D. Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood. 2004;103(12):4619–4621. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plumas J, Chaperot L, Richard MJ, Molens JP, Bensa JC, Favrot MC. Mesenchymal stem cells induce apoptosis of activated T cells. Leukemia. 2005;19(9):1597–1604. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aggarwal S, Pittenger MF. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood. 2005;105(4):1815–1822. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559. ▪ Details interactions between bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and immune cells and elucidates mechanisms likely involved in mesenchymal stem cell modulation of inflammation.

- 20.Potian JA, Aviv H, Ponzio NM, Harrison JS, Rameshwar P. Veto-like activity of mesenchymal stem cells: functional discrimination between cellular responses to alloantigens and recall antigens. J. Immunol. 2003;171(7):3426–3434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang SH, Park MJ, Yoon IH, et al. Soluble mediators from mesenchymal stem cells suppress T cell proliferation by inducing IL-10. Exp. Mol. Med. 2009;41(5):315–324. doi: 10.3858/emm.2009.41.5.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asari S, Itakura S, Ferreri K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells suppress B-cell terminal differentiation. Exp. Hematol. 2009;37(5):604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmusson I, Le Blanc K, Sundberg B, Ringden O. Mesenchymal stem cells stimulate antibody secretion in human B cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2007;65(4):336–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramasamy R, Fazekasova H, Lam EW, Soeiro I, Lombardi G, Dazzi F. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation and function by preventing entry into the cell cycle. Transplantation. 2007;83(1):71–76. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000244572.24780.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Djouad F, Charbonnier LM, Bouffi C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the differentiation of dendritic cells through an interleukin-6-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2007;25(8):2025–2032. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spaggiari GM, Abdelrazik H, Becchetti F, Moretta L. MSCs inhibit monocyte-derived DC maturation and function by selectively interfering with the generation of immature DCs: central role of MSC-derived prostaglandin E2. Blood. 2009;113(26):6576–6583. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Selmani Z, Naji A, Gaiffe E, et al. HLA-G is a crucial immunosuppressive molecule secreted by adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Transplantation. 2009;87 Suppl. 9:S62–S66. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a2a4b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. 2006;107(4):1484–1490. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortiz LA, Dutreil M, Fattman C, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist mediates the antiinflammatory and antifibrotic effect of mesenchymal stem cells during lung injury. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104(26):11002–11007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raffaghello L, Bianchi G, Bertolotto M, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit neutrophil apoptosis: a model for neutrophil preservation in the bone marrow niche. Stem Cells. 2008;26(1):151–162. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Latsinik NV, Panasyuk AF, Keiliss-Borok IV. Stromal cells responsible for transferring the microenvironment of the hemopoietic tissues. Cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation. 1974;17(4):331–340. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koc ON, Gerson Sl, Cooper BW, et al. Rapid hematopoietic recovery after coinfusion of autologous-blood stem cells and culture-expanded marrow mesenchymal stem cells in advanced breast cancer patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18(2):307–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Le Blanc K, Frassoni F, Ball L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a Phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Blanc K, Rasmusson I, Sundberg B, et al. Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1439–1441. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ringden O, Uzunel M, Rasmusson I, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation. 2006;81(10):1390–1397. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polchert D, Sobinsky J, Douglas G, et al. IFN-γ activation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment and prevention of graft versus host disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008;38(6):1745–1755. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Augello A, Tasso R, Negrini SM, Cancedda R, Pennesi G. Cell therapy using allogeneic bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells prevents tissue damage in collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1175–1186. doi: 10.1002/art.22511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerdoni E, Gallo B, Casazza S, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells effectively modulate pathogenic immune response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Ann. Neurol. 2007;61(3):219–227. doi: 10.1002/ana.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]