Abstract

Purpose

FUS1, a novel tumor-suppressor gene located in the chromosome 3p21.3 region, may play an important role in lung cancer development. Currently, FUS1-expressing nanoparticles have been developed for treating patients with lung cancer. However, the expression of Fus1 protein has not been examined in a large series of lung cancers and their sequential preneoplastic lesions.

Experimental Design

Using tissue microarrays, we examined Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in 281 non – small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) and 22 small cell lung carcinoma tissue specimens and correlated the findings with patients’ clinicopathologic features. To investigate the expression of Fus1 in the early sequential pathogenesis of NSCLC, we studied Fus1 expression in 211 histologically normal and mildly abnormal bronchial epithelia, and 118 bronchial and alveolar preneoplastic lesions obtained from patients with lung cancer.

Results

Loss and reduction of expression was detected in 82% of NSCLCs and 100% of small cell lung carcinomas. In NSCLCs, loss of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression was associated with significantly worse overall survival. Bronchial squamous metaplastic and dysplastic lesions expressed significantly lower levels of Fus1 compared with normal (P = 0.014 and 0.047, respectively) and hyperplastic (P = 0.013 and 0.028, respectively) epithelia.

Conclusions

Our findings show a high frequency of Fus1 protein loss and reduction of expression in lung cancer, and suggests that this reduction may play an important role in the early pathogenesis of lung squamous cell carcinoma. These findings support the concept that FUS1 gene and Fus1 protein abnormalities could be used to develop new strategies for molecular cancer therapy for a significant subset of lung tumors.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States (1). Lung cancer consists of several histologic types (2), the most frequent being small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) and two types of non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma (3). In spite of advances, the underlying processes involved in the early pathogenesis of lung cancer remain unclear. NSCLCs are believed to arise after the progression of sequential preneoplastic lesions, including bronchial squamous dysplasias for squamous cell carcinoma and atypical adenomatous hyperplasias (AAH) for a subset of adenocarcinomas (4). An increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis and progression of lung cancer may lead to new and more effective strategies for early detection and targeted chemoprevention and treatment.

Tumor-suppressor genes play a major role in the pathogenesis of human lung and other cancers (2). Lung cancer cells harbor mutations and deletions in multiple known tumor-suppressor genes; however, genetic alterations and allelic losses (loss of heterozygosity) on the short arm of chromosome 3 sites (3p25–26, 3p21.3–22, 3p14, and 3p12) are among the most frequent and earliest molecular abnormalities detected in the pathogenesis of lung cancer (5, 6). In particular, chromosomal abnormalities at the 3p21.3 region and expressional deficiencies in 3p21.3 genes are frequently found in lung cancer (7). In addition, 3p21.3 allelic losses have been frequently detected in histologically normal bronchial epithelia and preneoplastic lesions in lung cancer patients and smokers (6, 8).

The novel FUS1 gene is one of the candidate tumor-suppressor genes that have been identified in a 120-kb homozygous deletion region in human chromosome 3p21.3 (5, 9–11). Genomic alterations of the FUS1 gene and resultant loss of expression or deficiency of posttranslational modification of the Fus1 protein have been found in a majority of NSCLC cell lines and in almost all SCLCs (9–11). Recently, it was reported that Fus1 is a myristoylated protein and that myristoylation in its NH2 terminus is required for FUS1-mediated tumor suppression activity (9). Immunohistochemical Fus1 expression examination of 20 NSCLC tissue specimens showed loss of protein in 15 of 20 (75%) cases, and these findings were confirmed by mass spectrometric analysis (11). To translate these findings into clinical applications for molecular cancer therapy, a novel FUS1-expressing nanoparticle has been developed for treating patients with lung cancer (12), suggesting that FUS1 gene and protein abnormalities could be used to develop new strategies for molecular cancer therapy. To date, however, the expression of Fus1 has not been studied comprehensively in lung cancer tumors and lung preneoplastic lesion tissues.

To better understand the importance of Fus1 expression in lung cancer pathogenesis and progression, we investigated Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in a large series of NSCLC and SCLC tumor tissue specimens and adjacent lung bronchial and alveolar epithelial foci using tissue microarray specimens, and we correlated those findings with the clinico-pathologic features of patients with lung cancer.

Materials and Methods

Case selection and tissue microarray construction

We obtained archival, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded material from surgically resected lung cancer specimens containing tumor and adjacent lung tissues from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence Tissue Bank at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) from 1997 to 2001. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Tumor tissue specimens from 303 lung cancers (22 SCLCs, 172 adenocarcinomas, and 109 squamous cell carcinomas) were histologically examined, classified using the 2004 WHO classification system (3), and selected for tissue microarray construction. After histologic examination, the tissue microarrays were constructed using triplicate 1 mm diameter cores from each tumor.

Detailed clinical and pathologic information, including demographic data, smoking history (never- and ever-smokers) and status (never, former, and current smokers), pathologic tumor-node-metastasis staging (13), overall survival, and time of recurrence, was available in most cases (Table 1). Patients who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime were defined as smokers, and smokers who quit smoking at least 12 months before lung cancer diagnosis were defined as former smokers.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinicopathologic data regarding the lung cancer and respiratory epithelial samples studied for Fus1 immunohistochemical expression

| Type and histology of samples | No. | Sex |

Stage* |

Smoking history† |

Smoking status‡ |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | I | II | III | IV | Yes | No | Never | Former | Current | ||

| Total cancers | 303 | 155 | 148 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| SCLC | 22 | 7 | 15 | — | — | — | — | 22 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| NSCLC | 281 | 148 | 133 | 178 | 57 | 38 | 8 | 194 | 80 | 80 | 117 | 73 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 172 | 105 | 67 | 118 | 22 | 27 | 5 | 108 | 61 | 61 | 63 | 41 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 109 | 43 | 66 | 60 | 35 | 11 | 3 | 86 | 19 | 19 | 54 | 32 |

| Total epithelial foci | 329 | 136 | 193 | — | — | — | — | 274 | 50 | 50 | 120 | 145 |

| Normal epithelium | 68 | 35 | 33 | — | — | — | — | 53 | 15 | 15 | 26 | 27 |

| Hyperplasia | 120 | 31 | 89 | — | — | — | — | 107 | 11 | 11 | 50 | 57 |

| Squamous metaplasia | 23 | 10 | 13 | — | — | — | — | 18 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 9 |

| Low grade dysplasia | 14 | 6 | 8 | — | — | — | — | 14 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 6 |

| High grade dysplasia | 48 | 12 | 36 | — | — | — | — | 44 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 24 |

| AAH | 56 | 42 | 14 | — | — | — | — | 38 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 22 |

Staging is shown only for NSCLC cases. All SCLCs were limited stage.

Patient smoking history was not available for seven NSCLC and five epithelial specimens.

Patient smoking status was not available for 12 SCLC, 11 NSCLC, and 14 epithelial specimens.

To assess Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in the pathogenesis of NSCLC from the surgically resected formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens, we included 329 bronchial epithelium specimens which had normal histology (n = 68), basal cell hyperplasia (n = 120), squamous metaplasia (n = 23), squamous dysplasia (n = 62), and AAH lesions (n = 56) for analysis (Table 1). Histologic classification of epithelial lesions was done using the 2004 WHO classification system for lung preneoplastic lesions (3). For Fus1 expression analysis, squamous dysplasias were arranged into two groups: (a) low-grade, mild and moderate dysplasias (n = 14); and (b) high-grade, severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (n = 48).

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation

The rabbit anti-Fus1 polyclonal antibody used for immunohistochemical staining was raised against a synthetic oligopeptide derived from NH2-terminal amino acid sequence (NH2-GASGSKARGLWPFAAC; ref. 11). Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue histology sections (5 µm thick) were deparaffinized, hydrated, and heated in a steamer for 10 min with 10 mmol/L of sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for antigen retrieval. Peroxide blocking was done with 3% H2O2 in methanol at room temperature for 15 min, followed by 10% bovine serum albumin in TBS-t for 30 min. The slides were incubated with primary antibody at 1:400 dilution for 65 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, incubation with biotin-labeled secondary antibody for 30 min followed. Finally, the samples were incubated with a 1:40 solution of streptavidin-peroxidase for 30 min. The staining was then developed with 0.05% 3′,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride prepared in 0.05 mol/L of Tris buffer at pH 7.6 containing 0.024% H2O2 and then counterstained with hematoxylin. Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lung tissues with normal bronchial epithelia were used as a positive control. For a negative control, we used the same specimens used for the positive controls, replacing the primary antibody with PBS.

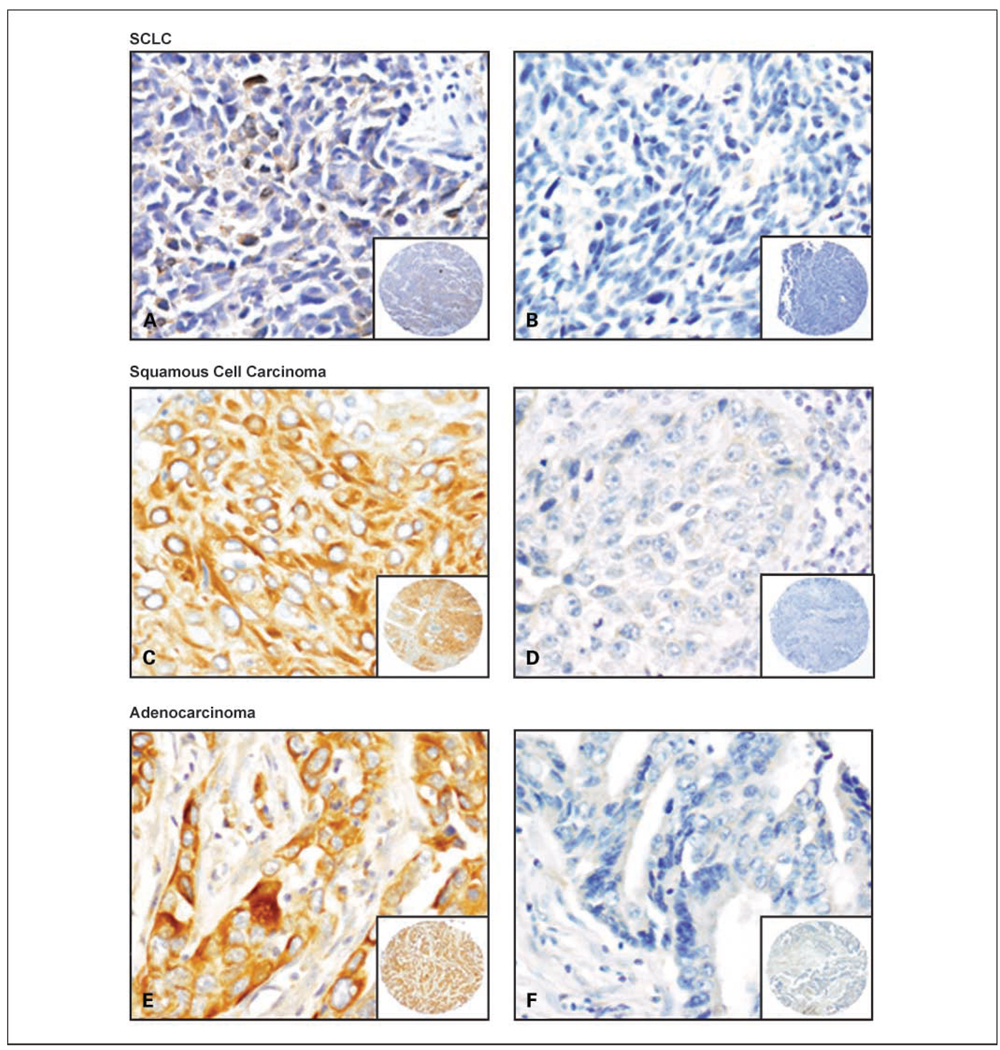

Fus1 immunostaining was detected in the cytoplasm of epithelial and tumor cells (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical expression was quantified by two independent pathologists (L. Prudkin and I.I. Wistuba) using a four-value intensity score (0, 1+, 2+, and 3+) and the percentage of the reactivity extent. A consensus value on both intensity and extension was reached by the two independent observers. Correlation analyses were done between the three quantifications and all showed statistical significance (r = 0.75; P < 0.001). A final consensual score was obtained by multiplying both intensity and extension values (range, 0–300), and four levels of staining were calculated based on that score: (a) negative (score 0), (b) low (score ≤100), (c) intermediate (score >100 to ≤200), and (d) and high (score >200) expressions. On the basis of the high level of expression detected in normal bronchial epithelium specimens, high score levels were defined as preserved staining pattern, whereas intermediate and low score levels were defined as reduced staining pattern, and negative score as loss of expression. Levels and scores were used for analysis.

Fig. 1.

Representative examples of Fus1 immunohistochemical staining of lung cancer specimens. SCLC with reduced (A) and negative (B) Fus1 expression. Squamous cell carcinoma with high (C) and negative (D) Fus1 expression. Adenocarcinoma with high (E) and negative (F) Fus1 expression. A to F, original magnification, ×400 (pictures), and ×40 (insets).

Statistical analysis

The data were summarized using standard descriptive statistics and frequency tabulations. Associations between categorical variables were assessed via cross-tabulation, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test. Wilcoxon rank sum test and Kruskal-Wallis test were done to assess the differences between patients’ clinicopathologic groups with respect to continuous variables. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the effect of covariates on overall survival and recurrence-free survival. All computations were done using SAS and Splus 2000 (Insightful) statistical software. The mixed effect model was used to assess the differences in scores between normal and abnormal epithelia. The generalized estimating equation approach was used to estimate differences in the means for the data in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in lung cancer and epithelial foci using tissue microarray specimens

| Histology of samples |

No. of samples |

Fus1 score, mean (SD) |

Fus1 score levels |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost (negative) n (%) |

Reduced (low + intermediate) n (%) |

Preserved (high) n (%) |

P value, Fus1 levels | ||||

| Cancer specimens | Comparison between tumors | ||||||

| SCLC | 22 | 57 (67.4) | 9 (41) | 13 (59) | 0 | 0.0008 | |

| NSCLC | 281 | 121 (87.3) | 36 (13) | 194 (69) | 51 (18) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 172 | 127 (91.8) | 25 (15) | 110 (64) | 37 (22) | 0.07 | |

| Squamous cell Carcinoma | 109 | 111 (79.1) | 11 (10) | 84 (77) | 14 (13) | ||

| Epithelial specimens | Comparison between normal and abnormal epithelia* |

||||||

| Score | Level | ||||||

| Normal epithelium | 68 | 251 (46.6) | 0 | 27 (40) | 41 (60) | Ref† | Ref† |

| Basal cell hyperplasia | 120 | 263 (47.5) | 0 | 40 (33) | 80 (67) | 0.35 | 0.68 |

| Squamous metaplasia | 23 | 215 (46.0) | 0 | 18 (78) | 5 (22) | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Squamous dysplasia | 62 | 224 (51.3) | 0 | 25 (45) | 31 (55) | 0.0004 | 0.047 |

| Low-grade dysplasia | 14 | 200 (39) | 0 | 12 (86) | 2 (14) | 0.010 | 0.28 |

| High-grade dysplasia | 48 | 231 (53) | 0 | 23 (48) | 25 (52) | 0.005 | 0.019 |

| AAH | 56 | 250 (52.3) | 0 | 25 (45) | 31 (55) | 0.61 | 0.79 |

Mixed effect model was used to assess difference of scores between normal and abnormal epithelia. A GEE model was used to compare the differences in FUS1 level between normal and abnormal epithelia.

Normal epithelium was used as reference value (Ref).

Results

Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in lung cancer specimens

Lung cancer histologies varied in their pattern of immunohistochemical expression of Fus1 in the cytoplasm of the tumor cells. We detected a statistically significant difference (P = 0.001) in the Fus1 expression mean score among the three major types of lung cancer histologies examined. SCLCs had the lowest mean score (57; SD, 67.4), with tumors having either no protein expression (41%) or reduced expression (59%; Table 2; Fig. 1). Squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas showed intermediate levels of Fus1 expression, with mean scores of 127 (SD, 91.8) and 111 (SD, 79.1), respectively. Overall, 82% (230 of 281) of NSCLCs had lower Fus1 expressions (69%) or no Fus1 expression (13%). We note that the difference between squamous cell and adenocarcinoma histologies was not shown to be statistically significant at the 0.05 level (P = 0.07; Table 2). There was a significant difference (P = 0.0008) in the levels of Fus1 expression between SCLCs and NSCLCs (Table 2). Overall, lung tumor specimens showed lower scores and levels of expression compared with normal epithelium. Most tumors (231 out of 303, 76%; 91% of SCLCs and 75% of NSCLCs) had a score of <200, which was never associated with normal tissue.

Correlation between Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in NSCLC and clinicopathologic features

Using Fus1 expression mean scores and score levels, we detected no statistically significant correlation and/or association between protein expression and the clinicopathologic data, including sex, age, ethnicity, smoking history, and tumor-node-metastasis pathologic stage. Overall and disease-free survival analyses for Fus1 expression were done in 280 patients with tumor-node-metastasis stages I to IV (median follow-up, 3.90 years), and in 218 patients with stages I and II (median follow-up, 4.03 years) NSCLCs, who did not receive neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapies. Of interest, in both univariate and multivariate Cox model analyses, the hazard ratios for overall survival were much lower in cases having any level of Fus1 expression (low, intermediate, and high) compared with absence (negative) of protein expression (Table 3). These differences were statistically significant in most comparisons. Although the hazard ratios for recurrence-free survival showed similar trends than overall survival, the P values were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox model assessing effects of covariates on overall survival

| (A) Univariate Cox model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | All stages (n = 280) |

Stages I and II (n = 213) |

|||

| Hazard ratio | P | Hazard ratio | P | ||

| Age | 1.044 | <0.0001 | 1.057 | <0.0001 | |

| Histology | Squamous cell vs. adenocarcinoma | 1.585 | 0.02 | 1.667 | 0.03 |

| Tumor* | T 2 + 3 + 4 vs. T1 | 2.024 | 0.002 | — | — |

| T2 + 3 vs. T1 | — | — | 2.175 | 0.002 | |

| Lymph node* | N1 + 2 vs. N0 | 2.122 | 0.0003 | 2.531 | 0.0002 |

| N1 vs. N0 | — | — | — | — | |

| Tumor stage* | II + III + IV vs. I | 2.01 | 0.0005 | — | — |

| II vs. I | — | — | 2.47 | 0.0002 | |

| Fus1 score mean | 0.999 | 0.70 | 0.999 | 0.61 | |

| Fus1 score level | Low † vs. negative ‡ | 0.535 | 0.06 | 0.502 | 0.07 |

| Intermediate † vs. negative ‡ | 0.744 | 0.35 | 0.831 | 0.60 | |

| High§ vs. negative‡ | 0.685 | 0.28 | 0.536 | 0.13 | |

|

(B) Multivariate Cox model | |||||

| Variable |

All stages |

Stages I and II |

|||

| Hazard ratio | P | Hazard ratio | P | ||

| Age | 1.047 | <0.0001 | 1.059 | <0.0001 | |

| Histology | Squamous cell vs. adenocarcinoma | 1.528 | 0.04 | 1.438 | 0.13 |

| Tumor stage* | II + III + IV vs. I | 2.163 | 0.0002 | — | — |

| II vs. I | — | — | 2.519 | 0.0004 | |

| Fus1 score level | Low† vs. negative‡ | 0.357 | 0.002 | 0.312 | 0.003 |

| Intermediate† vs. negative‡ | 0.474 | 0.02 | 0.544 | 0.10 | |

| High§ vs. negative‡ | 0.518 | 0.06 | 0.415 | 0.03 | |

Pathologic tumor, lymph node, and metastasis stage.

Low and intermediate, reduced Fus1 immunohistochemical expression.

Negative, absence of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression.

High, preserved or normal Fus1 immunohistochemical expression.

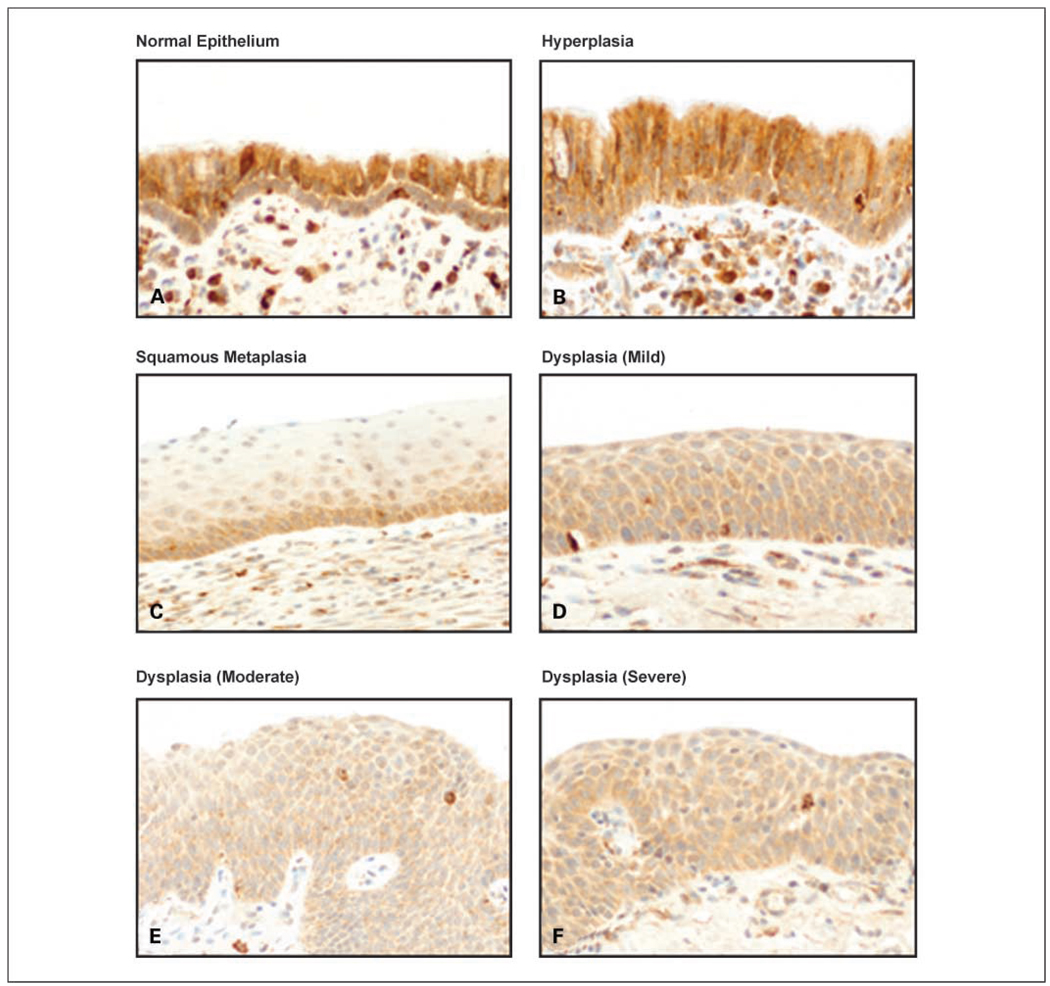

Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in the sequential pathogenesis of lung cancer

To characterize the pattern of Fus1 expression in the sequential pathogenesis of NSCLC, we investigated the protein immunohistochemical expression in histologically normal epithelium, hyperplasia, squamous metaplasia, and squamous dysplasia bronchial sites obtained from surgically resected NSCLC specimens (Fig. 2). We also examined 56 AAH lesions, a putative precursor lesion for adenocarcinomas (3, 4). Mean scores and score levels of Fus1 cytoplasmic expression in the epithelia were used for comparison between all different epithelial histologic categories. Overall, normal, mildly abnormal, and preneoplastic respiratory epithelia showed higher mean scores and score levels of Fus1 expression compared with tumors, and none of the nonmalignant epithelial specimens showed loss of expression. Normal and hyperplastic epithelia displayed high mean scores and score levels of Fus1 expression (Table 2), with high expression score levels in 60% (41 of 68) and 67% (80 of 120) of normal and hyperplastic foci, respectively. Squamous metaplasia and dysplasia lesions had significantly lower score means and score levels of Fus1 expression compared with histologically normal and hyperplastic epithelia, with 78% and 57% of the squamous metaplastic and dysplastic lesions, respectively, showing a lower protein expression (Table 2). No differences were detected in the level of Fus1 expression comparing low-grade (mild and moderate dysplasias) and high-grade (carcinoma in situ and severe dysplasia) squamous dysplastic lesions. No significant differences in the mean scores and score levels of Fus1 expression were detected comparing normal and hyperplastic bronchial epithelium with AAH lesions. No significant associations were observed between Fus1 expression and age, sex, or smoking status of NSCLCs patients from whom epithelial specimens were obtained.

Fig. 2.

Representative examples of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in histologically normal (A), hyperplastic (B), metaplastic (C), and dysplastic (D – F) bronchial epithelia. High levels of expression are shown in the normal and hyperplastic epithelia and reduced levels in squamous metaplasia and dysplasias. Original magnification, ×400.

Discussion

Mutations in 3p21.3 genes are rarely found in human tumors, including lung cancer (7). Therefore, some mechanisms other than the classic two-hit model, which requires mutation in one allele and silencing or loss on another allele, might be of importance in the ultimate inactivation of 3p21.3 genes. These alternative mechanisms include promoter methylation, haploinsufficiency, altered RNA splicing, as well as defects in transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational processes. In lung cancer, only a few FUS1 mutations that alter or truncate amino acid sequences have been detected (7), and its promoter methylation is a rare phenomenon (11). It has been hypothesized that this gene is inactivated in lung tumors by alternative mechanisms, such as influence from the stochastic effects of 3p21.3 allele haploinsufficiency (6) and a posttranslational modification of the gene product by deficient N-myristoylation of the Fus1 protein (11). It has been shown that myristoylation is required for FUS1-mediated tumor-suppressing activity, suggesting a novel mechanism for the inactivation of tumor-suppressor genes for human cancers (11). Uno et al. (11), using surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, analyzed the N-myristoylation status of Fus1 protein in frozen lung cancer tissue specimens and determined that protein loss of immunohistochemical expression correlated with loss of protein myristoylation.

Thus, to investigate the frequency and pattern of Fus1 protein expression abnormalities in lung cancer, we examined the immunohistochemical expression of the protein using tissue microarrays in a large series of primary tumor specimens with annotated clinical information. Our findings confirmed and further expanded previously reported data on loss of Fus1 protein expression in 20 NSCLC tissue specimens (11). Lung tumors showed lower levels of expression than normal bronchial epithelium. We found that loss or reduction of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression was present in all SCLCs and most (82%) of the NSCLCs (87% of the squamous cell carcinomas and 79% of the adenocarcinomas). Fus1 protein expression was absent in half of the SCLCs and in 13% of the NSCLCs. For NSCLCs, we found that loss of Fus1 expression is a significant independent adverse prognostic factor for patients’ overall survival. Our findings that retention of any level of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression significantly correlates with better outcome in NSCLC are in agreement with the potent effect of tumor suppressor activity of FUS1 gene as shown by in vitro and in vivo studies (11, 12). Although FUS1 is one of the nine putative tumor-suppressor genes located in the 3p21.3 region frequently deleted in lung and other tumor sites (7), our study is the first report on Fus1 protein expression abnormalities in a large series of human tumors arising at any site.

The ability to rescue the tumor phenotype by gene inactivation after the replacement of those genes is one of the criteria needed for a gene to be considered a tumor-suppressor gene. There is evidence indicating that the replacement of FUS1 in nonexpressive NSCLC cell lines inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis (9, 10). More importantly, Ji et al. (9) showed that intratumoral injection of adenovirus-FUS1 significantly reduces tumor growth in FUS1 region–deficient tumor xenografts and experimental metastasis. Following in vitro results, Ito et al. (12) reported that intratumoral and intravenous administration of FUS1 complexed to nanoparticles in mice bearing human lung cancer cell line xenografts resulted in the inhibition of tumor growth, a decreased number of metastases, and prolonged survival compared with results for untreated animals. The restoration of tumor-suppressor genes altered in cancer development is currently a valid therapeutic approach. On the basis of preclinical studies, a phase I clinical trial by our group using FUS1-mediated molecular therapy by systemic administration of FUS1-nanoparticles is currently under way in stage IV NSCLC patients at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. Our findings of a lack or reduction of expression of Fus1 protein in most lung tumors supports the concept of the delivery of functional FUS1 as an effective therapeutic strategy for human lung cancer.

Lung cancers are believed to be the consequence of a series of progressive preneoplastic changes in the respiratory mucosa that accumulate a sequence of genetic changes (14). These genetic abnormalities are frequently extensive and multifocal throughout the respiratory epithelium, indicating a field effect or field cancerization phenomenon (4). Although the sequential preneoplastic changes have been defined for squamous carcinomas, they have been poorly documented for lung adenocarcinomas and SCLCs (4). Mucosal changes in the large airways that may precede squamous cell carcinoma include squamous dysplasia and carcinoma in situ in the central airway (15, 16). Adenocarcinomas may be preceded by morphologic changes, including AAH in peripheral airway cells (17). In squamous cell carcinoma pathogenesis, genetic abnormalities commence in histologically normal epithelium and augment with increasing severity of histologic changes, with 3p21.3 allelic loss as the earliest genetic change being detected in patients with lung cancer and smokers (6, 8). Our findings of a significant reduction of Fus1 protein immunohistochemical expression in squamous metaplasia and dysplasia histologies compared with histologically normal and hyperplastic epithelia suggest that the reduction and partial inactivation of 3p21.3 FUS1 gene expression is an early phenomenon in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma. AAH lesions showed some reduction in the level of Fus1 immunohistochemical expression in a subset of cases (45%), but no differences compared with histologically normal and hyperplastic epithelia were detected. Although 3p12 and 3p14 allelic losses have been shown in ~ 20% of AAHs, no detailed mapping analysis of chromosome 3p that includes the FUS1 3p21.3 region has been done in these lesions (18).

Although a total loss of Fus1 protein immunohistochemical expression was detected in 50% of SCLCs and in 13% of NSCLSs, no normal and abnormal epithelial sites showed a complete lack of Fus1 protein expression. Because most lung cancers and adjacent preneoplastic lesions have shown allelic loss at the 3p21.3 region (6), FUS1 haploinsufficiency may play a role in the inactivation of Fus1 protein in lung cancer pathogenesis (19). In diploid cells, each gene exists in two copies, in contrast to haploids in which each cell contains a single copy of the genome. When one of the alleles is mutated or deleted, there is an ~ 50% reduction in the level of proteins synthesized. Generally, the haploinsufficiency occurs when the level of proteins synthesized decreases below a threshold level and is insufficient for the onset of some desired biological activity. We have detected lower Fus1 protein expression in a subset of all epithelial foci examined, including histologically normal, hyperplastic, metaplastic, and preneoplastic epithelia. Interestingly, the reduction of Fus1 expression in epithelial specimens, including 40% of histologically normal epithelia, was observed in samples from both smoker and never-smoker NSCLC patients, suggesting that this phenomenon is not necessarily associated with smoking. We speculate that allelic loss and the haplotype in the FUS1 3p21.3 region at very early stages of lung tumor pathogenesis may lead to a reduction of Fus1 protein synthesis. We hypothesize that a deficiency in myristoylation might lead to a greater reduction and complete loss of Fus1 protein expression in the later stages of tumor development, such as in microinvasive and invasive lesions.

In summary, our findings show a high frequency of Fus1 protein reduction and loss of expression in SCLC and NSCLC tissue specimens, and suggest that reduction of this protein may play an important role in the early pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinomas. All these findings support the concept that FUS1 gene and protein abnormalities could be used to develop new strategies for molecular cancer therapy for a significant subset of lung tumors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Specialized Program of Research Excellence in Lung Cancer (grant P50CA70907), National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, and Department of Defense (grant W81XWH-04-1-0142).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minna JD, Roth JA, Gazdar AF. Focus on lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:49–52. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Lyon: IARC; 2004. Pathology and genetics: tumours of the lung, pleura and heart, editors. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wistuba I. Genetics of preneoplasia: lessons from lung cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:3–14. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerman MI, Minna JD. The 630-kb lung cancer homozygous deletion region on human chromosome 3p21.3: identification and evaluation of the resident candidate tumor suppressor genes. The International Lung Cancer Chromosome 3p21.3 Tumor Suppressor Gene Consortium. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6116–6133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wistuba II, Behrens C, Virmani AK, et al. High resolution chromosome 3p allelotyping of human lung cancer and preneoplastic/preinvasive bronchial epithelium reveals multiple, discontinuous sites of 3p allele loss and three regions of frequent breakpoints. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1949–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji L, Minna JD, Roth JA. 3p21.3 tumor suppressor cluster: prospects for translational applications. Future Oncol. 2005;1:79–92. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wistuba II, Lam S, Behrens C, et al. Molecular damage in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1366–1373. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji L, Nishizaki M, Gao B, et al. Expression of several genes in the human chromosome 3p21.3 homozygous deletion region by an adenovirus vector results in tumor suppressor activities in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2715–2720. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kondo M, Ji L, Kamibayashi C, et al. Overexpression of candidate tumor suppressor gene FUS1 isolated from the 3p21.3 homozygous deletion region leads to G1 arrest and growth inhibition of lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:6258–6262. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uno F, Sasaki J, Nishizaki M, et al. Myristoylation of the fus1 protein is required for tumor suppression in human lung cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2969–2976. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito I, Ji L, Tanaka F, et al. Liposomal vector mediated delivery of the 3p FUS1 gene demonstrates potent antitumor activity against human lung cancer in vivo. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:733–739. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mountain CF. Revisions in the International System for Staging Lung Cancer. Chest. 1997;111:1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wistuba II, Mao L, Gazdar AF. Smoking molecular damage in bronchial epithelium. Oncogene. 2002;21:7298–7306. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colby TV, Wistuba II, Gazdar A. Precursors to pulmonary neoplasia. Adv Anat Pathol. 1998;5:205–215. doi: 10.1097/00125480-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hastings RH, Auger WR, Kerr KM, Quintana RA, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and lung injury after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Regul Pept. 2001;102:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(01)00304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westra WH, Slebos RJ, Offerhaus GJ, et al. K-ras oncogene activation in lung adenocarcinomas from former smokers. Evidence that K-ras mutations are an early and irreversible event in the development of adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 1993;72:432–438. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<432::aid-cncr2820720219>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamasaki M, Takeshima Y, Fujii S, et al. Correlation between genetic alterations and histopathological subtypes in bronchiolo-alveolar carcinoma and atypical adenomatous hyperplasia of the lung. Pathol Int. 2000;50:778–785. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zabarovsky ER, Lerman MI, Minna JD. Tumor suppressor genes on chromosome 3p involved in the pathogenesis of lung and other cancers. Oncogene. 2002;21:6915–6935. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.