Abstract

Distal hereditary motor neuropathies comprise a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders. We recently mapped an X-linked form of this condition to chromosome Xq13.1-q21 in two large unrelated families. The region of genetic linkage included ATP7A, which encodes a copper-transporting P-type ATPase mutated in patients with Menkes disease, a severe infantile-onset neurodegenerative condition. We identified two unique ATP7A missense mutations (p.P1386S and p.T994I) in males with distal motor neuropathy in two families. These molecular alterations impact highly conserved amino acids in the carboxyl half of ATP7A and do not directly involve the copper transporter's known critical functional domains. Studies of p.P1386S revealed normal ATP7A mRNA and protein levels, a defect in ATP7A trafficking, and partial rescue of a S. cerevisiae copper transport knockout. Although ATP7A mutations are typically associated with severe Menkes disease or its milder allelic variant, occipital horn syndrome, we demonstrate here that certain missense mutations at this locus can cause a syndrome restricted to progressive distal motor neuropathy without overt signs of systemic copper deficiency. This previously unrecognized genotype-phenotype correlation suggests an important role of the ATP7A copper transporter in motor-neuron maintenance and function.

Introduction

The distal hereditary motor neuropathies (distal HMNs) comprise a clinically and genetically heterogeneous group of disorders predominantly affecting motor neurons in the peripheral nervous system.1 Affected distal HMN individuals manifest progressive weakness and wasting beginning in the distal muscles of the limbs and have no notable sensory symptoms. Distal HMNs have been classified into seven subgroups based on mode of inheritance, age of onset, distribution of muscle weakness, and clinical progression.2 Fifteen genetic loci for distal HMN have been mapped, and eight genes have been identified.3 These encode a functionally diverse array of gene products, including a transfer RNA synthetase,4 two heat-shock proteins,5,6 and a microtubule motor protein involved in axonal transport.7 A form of distal HMN with linkage to chromosome Xq13.1-q21 (DSMAX; SMAX3 [MIM 300489]) was reported in a Brazilian family.8 We recently mapped and refined this locus in a second unrelated North American family of European descent.9 The 14.2 Mb region contained more than 50 annotated genes, including ATP7A (MIM 300011), which encodes a copper-transporting P-type ATPase.9

Copper is an essential trace metal with potential toxicity and requires exquisite homeostatic control; its regulation involves mechanisms governing gastrointestinal uptake, transport to the developing brain, targeted intracellular delivery to copper enzymes, and hepatic excretion of copper into the biliary tract.10–13 These functions are largely fulfilled by a pair of evolutionarily related copper-transporting ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B (MIM 606882). The ATP7A gene is mutated in Menkes disease (MK; MNK [MIM 309400]), a severe infantile-onset developmental disorder.14–17 An allelic variant, occipital horn syndrome (OHS [MIM 304150]), is similar in many clinical and biochemical aspects, although the neurologic phenotype is far less severe.18,19 Neither condition features overt motor neuropathy.

In this study, we evaluated the ATP7A copper transporter in two families whose affected members had X-linked distal motor neuropathy.

Material and Methods

Subjects

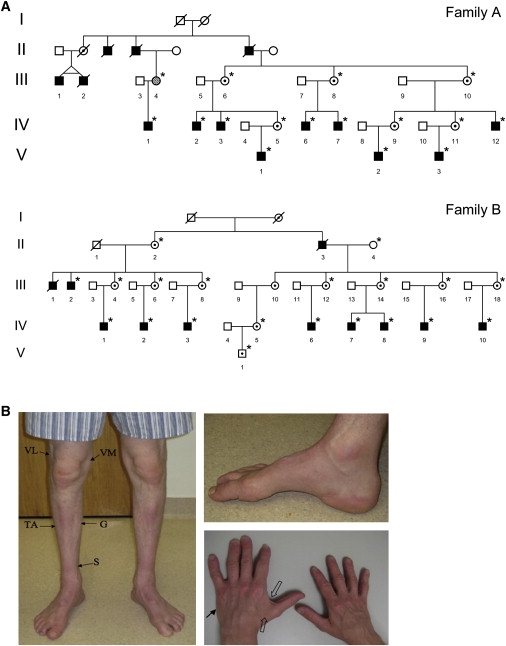

Pedigrees and linkage studies were previously reported for the North American and Brazilian families. Family A (North American) and family B (Brazilian) (Figure 1A) demonstrated X-linked inheritance of a distal motor neuropathy phenotype (Figure 1B) defined by decreased motor action potentials, normal nerve conduction velocities, and limited or no sensory involvement.1 Both families are of European descent. A total of 31 individuals from family A and 30 individuals from family B were examined for neurological signs. Clinical, biochemical, and electrophysiologic findings in affected members of these families are summarized (Table 1). The ethics review committees of all participating institutions approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from subjects or parents of subjects less than 18 years of age.

Figure 1.

Inheritance Pattern and Clinical Findings in X-Linked Distal Motor Neuropathy

(A) Pedigrees of family A, modified from Kennerson et al.,9 and family B, modified from Takata et al.8 The pedigrees show the key branches of the families with affected individuals. Squares indicate males, and circles indicate females. Solid symbols denote affected family members, and open symbols denote unaffected family members. The hatched circle (III-4 in family A) indicates an asymptomatic female with minimal clinical signs of motor neuron disease. Internal dots indicate obligate gene carriers. Asterisks denote individuals who are confirmed carriers of the gene mutations and were examined by one or more of the authors in this study. Diagonal lines through symbols indicate deceased individuals.

(B) Clinical findings in X-linked distal motor neuropathy. Evidence of distal muscle wasting in a 43-year-old male (IV-2, family A; Figure 1A) with the P1386S ATP7A mutation. Both legs showed decreased mass of the vastus lateralis (VL), vastus medialis (VM), tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (G), and soleus (S) muscles. Both feet showed pes cavus deformities. There was moderate wasting of the first dorsal interosseus (open arrows) and the hypothenar (arrow) muscle groups of the hand. The patient's hair was normal in texture and had no pili torti under light microscopy. The palate showed normal contour. The thorax showed no deformities, and the cardiac and pulmonary examinations were normal. The joints and skin did not show excessive laxity. Radiographic studies showed no wormian bones of the skull, no occipital exostoses, and normal clavicular heads. Plasma catecholamine ratios and the urine concentration of beta-2-microglobulin, biomarkers often elevated in Menkes disease,22 were normal.

Table 1.

Clinical, Neurophysiologic, and Biochemical Features in Study Subjects

| Family/ Patient | Age (yr) |

Onset (yr) |

Weakness | Atrophy | Sensory Exam | DTRs |

Median CMAP (mV) |

Median NCV (m/s) |

Tibial CMAP (mV) |

Median SNAP (μV) |

Serum Cu (nmol/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/III-4 | 52 | ∼50 | Mild distal L > A | Mild H | Normal | Absent Achilles | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| A/IV-1 | 22 | ∼4 | Moderate distal L, mild H | F, mild H | Normal | Absent Achilles | 4.3 | 57.6 | 1.9 | 13.3 | NR |

| A/IV-2 | 43 | ∼15 | Distal, L > A | F, lower L, H | Mild distal toes, fingers | Absent Achilles | 2.62 | 61.5 | 2.80 | 26.6 | 15.4 |

| A/IV-3 | 44 | 10 | Distal, L > A | F, Distal L, H | Mild distal lower L | Absent Achilles | 3.6 | 46.8 | NR | 17 | NR |

| A/IV-6 | 62 | 61 | Mild distal L | Mild distal L, F | Mod. distal L vibratory loss | Absent Achilles | NR | NR | 2.73 | NR | 13.2 |

| A/IV-7 | 53 | 30 | Mild L > A | H, F | Normal | Normal | 12.0 | 57.5 | 2.3 | NR | 12.5 |

| A/IV-12 | 57 | 10 | Distal L > A | F, distal L,H | Mild distal L reduction | Normal | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR |

| A/V-1 | 16 | 13 | Mild distal L | None | Normal | Normal | 6.3 | 64.7 | 13.5 | NR | NR |

| A/V-2 | 41 | 35 | Distal L | Mild F atrophy | Mild distal L sensory loss | Normal | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| A/V-3 | 33 | 25 | Mild H | Mild H | Normal | Normal | 8.0 | 56.8 | 4.8 | NR | NR |

| B/IV-2 | 26 | 8 | Distal L | Moderate distal A,L | Normal | Absent L | 2.7 | 50.5 | NR | 25.8 | 15.3 |

| B/IV-3 | 29 | 2 | Distal L, A | Severe distal L,F,H | Normal | Areflexic | 0.33 | 41.2 | 0.07 | 66.0 | 13.4 |

| B/V-1 | 5 | Absent | Absent | Normal | Normal | NR | NR | NR | 62.0 | NR | |

| Reference Ranges | |||||||||||

| ≥4 | ≥50 | ≥4 | >20 | 11-23.622 | |||||||

Abbreviations are as follows: L, leg; F, foot; H, hand; A, arm; DTR, deep tendon reflexes; CMAP, compound motor action potential; SNAP, sensory nerve action potential NR, not recorded. Reference ranges for neurophysiological measurements are from Clinical Neurophysiology.47

Mutation Analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood samples using standard protocols or saliva samples using the Oragene Kit (DNA Genotek). Mutation analysis was performed using high resolution melt protocols established in our laboratory.9 PCR amplicons for mutation scanning were designed to cover the coding exons and flanking intronic sequences. Primers for all genes including the ATP7A gene were designed using the LightScanner Primer Design Software (version 1.0.R.84 Idaho Technology). Melt acquisition was performed on a 96-well Light Scanner (Idaho Technology) and the data analyzed with Light Scanner Call-IT 2.0 (Version 2.0.0.1331). Amplicons of differential melt curves were sequenced using BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing protocols at the ACRF Facility, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Australia.

Cell Culture

Human fibroblast cells obtained by skin biopsies from affected patients from family A and B, a Menkes disease patient with deletion of ATP7A exons 20–23, a normal healthy male, and the fibroblast cell line GM3652 from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum under humidified air at 37°C in 5% CO2. Experimental variations in culture media or temperature are indicated in the text, figures, or legends where relevant. Copper concentrations in fibroblast tissue extracts were determined by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry as previously described.20

Real-Time Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was generated from 5 μg RNA with AffinityScript reverse transcriptase (Stratagene). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with specific primers for ATP7A (5′-GCTACCTTGTCAGACACGAATGAG-3′ and 5′-TCTTGAACTGGTGTCATCCCTTT-3′) and β-actin (5′-GACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGATTACT-3′ and 5′-TGATCCACATCTGCTGGAAGGT-3′) as previously described.21

Immunoblot Analysis

Total cell lysates were denatured by the addition of 5× loading buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Quality Biological) and heating at 50°C for 10 min. Samples (40 μg total protein) were electrophoresed through 4%–12% NOVEX Tris-glycerin SDS-poly-acrylamide (Invitrogen) and transferred to polyvinylidine fluoride membranes. Membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight in Tris-buffered saline blocking buffer (0.9% (v/v) NaCl, 20 mM Tris/HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5% SDS (v/v), 0.1% Tween 20 v/v) containing 5% (w/v) nonfat milk. Blots were washed three times for 5 min each with Tris-buffered saline, then incubated for 3 hr with a 1:1000 dilution of a rabbit ATP7A antibody raised against the carboxy-terminal 18 amino acids (NH2-DKHSLLVGDFREDDDTAL-COOH) of human ATP7A (Antibody Solutions). After being washed, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hr at room temperature, washed again, and developed with SuperSignal West Pico Luminol/Enhancer Solution (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After membranes were stripped, incubation with a primary mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed so that β-actin could be detected; an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent was used for development, as above.

Immunohistochemical Analysis and Confocal Microscopy

Dermal fibroblasts were fixed on glass slides with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde. Blocking was performed with 3% (v/v) goat serum at room temperature for 1 hr. Samples were incubated with the rabbit anti-human carboxy-terminal ATP7A primary antibody (described under Immunoblot Analysis) at a dilution of 1:2000 at 4°C overnight; subsequently, Texas Red-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes) was used as the secondary antibody for incubation at room temperature for 2 hr. Cells were viewed with a confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse, Nikon), and images captured with Confocal Assistant software.

ATP7A Trafficking

Fibroblasts were grown in duplicate on 12 mm glass coverslips in 24-well trays and cultured at 30°C for 16 hr. The growth media were replaced with either basal media (0.5−1 μM copper) or media supplemented with 200 μM CuCl2 for 3 hr. Fibroblasts were then fixed with 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min, and blocked with 1% BSA and 0.25% gelatin in PBS at room temperature for 20 min. Cells were incubated with the sheep anti-human N-terminal ATP7A antibody21 and a mouse monoclonal antibody to the trans Golgi marker p230 (BD Transduction Laboratories) diluted 1:1000 and 1:500, respectively, in 1% BSA at 4°C overnight and then with the secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (green) donkey anti-sheep IgG (Molecular Probes) (1:4000) or Alexa Fluor 594 (red) donkey anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes) at room temperature for 1 hr. Confocal images were collected with a Leica confocal microscope system TCS SP2 (Leica). As a semiquantitative assessment, normal control and affected patient fibroblasts were scored for ATP7A staining in the trans Golgi after copper exposure, and chi square analysis was used for statistical comparison. The trafficking experiments were performed in quadruplicate.

Yeast Complementation

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed as described19,22 for generation of the P1386S ATP7A mutant allele. Plasmid DNA from the yeast expression vector del20-23/pYES22 containing bases 1–3800 of the ATP7A cDNA was double-digested with SpeI and SacI so that a 523 bp fragment containing a KpnI restiction site would be removed from the plasmid sequence. The fragment was replaced by a 511 bp fragment without the KpnI site via PCR of pYES DNA with primers 5′GCGACTAGTACGGATTAGAAGCCGCCGAGCGGGTGACAGCCCTCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCGAGCTCAATATTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTACAG-3′ (reverse); T4 DNA ligase and an insert-to-vector ratio of 1.6:1 (35 fmoles: 22 fmoles) were used. The construct generated from this cloning was named del20-23/pYES/sKs (single KpnI site). A 501 bp fragment of the ATP7A cDNA then was excised from del20-23/pYES/sKs via double digestion with KpnI and ApaI, replaced with a 1201 bp fragment containing the P1386S mutation (C-to-T transition), and named P1386S/pYES/sKs. DNA fidelity was confirmed by automated sequencing. Yeast complementation and timed growth assays were carried out as previously described19,22 except that plates and liquid media contained 100 μg/ml blasticidin.

Results

Gene Mutation Analysis

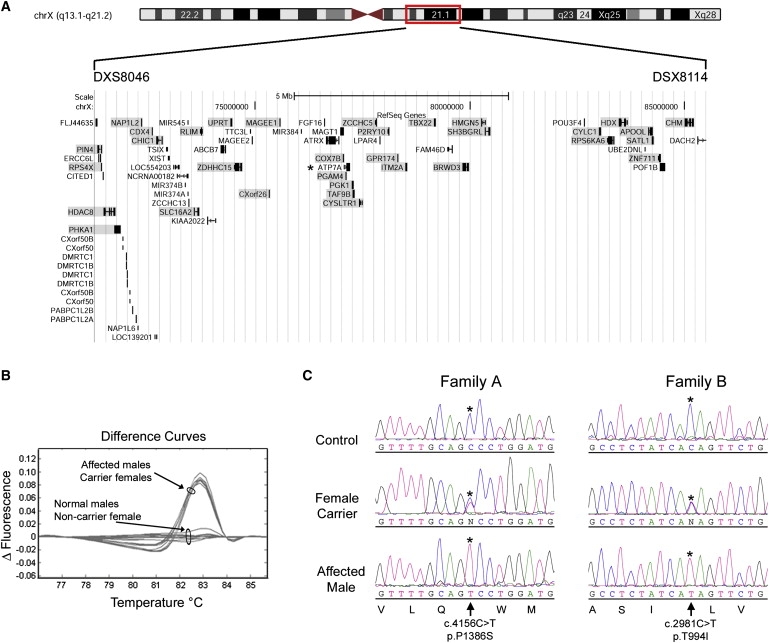

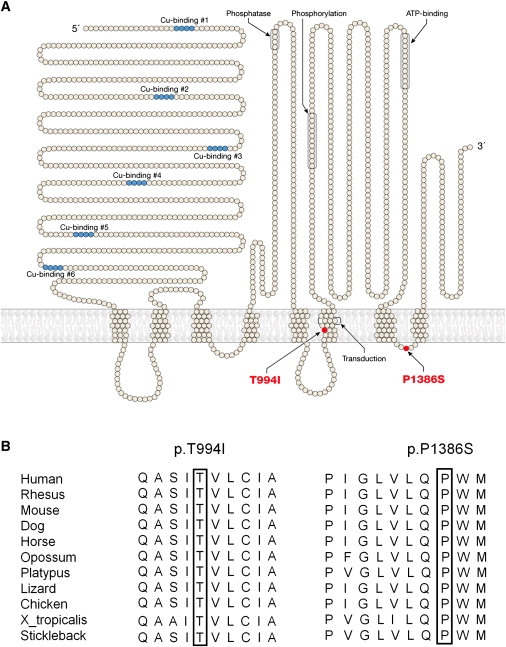

Thirty-three genes that underwent mutation analysis in this study are shown in Figure 2A. High-resolution melt analysis of ATP7A exon 22 showed differential subtractive melt curves between affected male/carrier female and normal male/noncarrier female groups in family A (Figure 2B). Sequence analysis of nine affected males identified a transition mutation of c.4156C > T in exon 22 (Figure 2C, family A), which predicts an amino acid substitution of p.P1386S. The alteration was not present in seven unaffected male members from family A. ATP7A was sequenced in ten affected males from family B, and a transition mutation of c.2981C > T in exon 15 was identified (Figure 2C, family B), predicting a p.T994I amino acid substitution. The alteration was not present in six unaffected males from family B. The p.P1386S and p.T994I, alterations were absent from 800 unrelated, ethnically matched control chromosomes. The documented mutations all occur in the carboxyl half of the ATP7A protein (Figure 3A) and are highly conserved (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Genetic Basis of X-linked Distal Motor Neuropathy

(A) Display of annotated genes in the interval between the markers DXS8046 and DXS8114; data are from the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) Genome Browser (Human March 2006 Assembly; NCBI Build 36.1). Redundant genes are not shown, and the coding region of genes formally excluded in family A are shaded. An asterisk denotes the ATP7A gene, which maps between PGAM4 and PGK1. High-resolution melt analysis was used for scanning all genes except for HDAC8, RLIM, and PGAM4, which underwent sequence analysis.9

(B) Subtractive difference plot for affected/carrier and normal/noncarrier samples in family A for exon 22 of ATP7A. The differential shape and grouping of affected/carrier and normal/noncarrier difference plots suggested that a DNA variant was segregating with the distal motor neuropathy phenotype in this family.

(C) Sequence data in affected males, carrier females, and normal males for p.P1386S and p.T994I. An asterisk denotes the base change resulting in missense mutations that segregate with distal motor neuropathy in the respective families. The GenBank sequences NM_00052 and NP_000043.3 were used as the reference sequences for the ATP7A cDNA and the ATP7A protein, respectively. Mutations are designated on the basis of numbering of the A in the ATG translation initiation site as +1.

Figure 3.

Locations and Sequence Alignments of ATP7A Mutations Causing Distal Motor Neuropathy

(A) Topological depiction of the p.T994I and p.P1386S mutations in the ATP7A copper-ATPase associated with distal hereditary motor neuropathy.

(B) Alignment analysis of the p.T994I and p.P1386S mutations for ATP7A orthologs in different species. Amino acid positions 994 and 1386 are boxed.

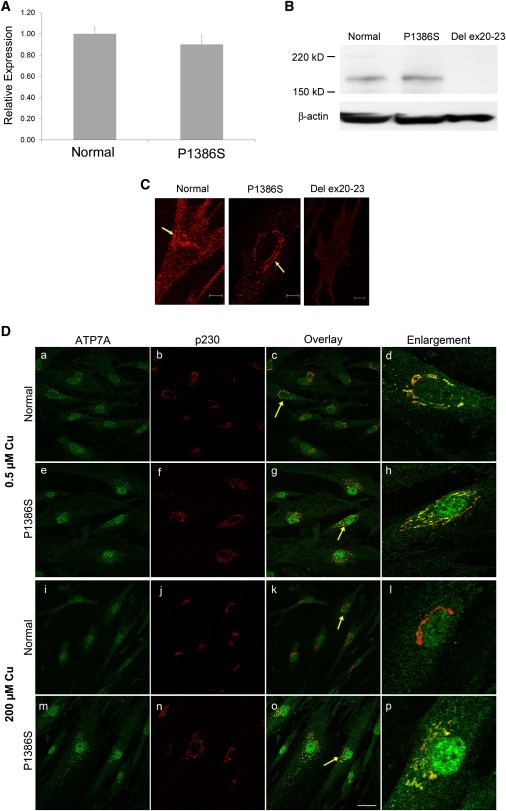

P1386S ATP7A RNA and Protein Analysis

We used quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting to determine whether mRNA and protein levels were altered in P1386S fibroblasts. The level of mRNA expression was not significantly changed (Figure 4A), and immunoblot analyses of fibroblast protein extracts (Figure 4B) showed a similar amount and size of the protein when these were compared to normal controls.

Figure 4.

Characterization of P1386S ATP7A

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR showing ATP7A mRNA levels from P1386S fibroblasts relative to control fibroblasts from a normal individual. The error bars indicate standard deviation. Each sample was run in triplicate.

(B) Immunoblot showing the proper size (≈178 kDa) and amount of ATP7A from P1386S fibroblasts relative to a normal control (fibroblast cell line GM3652). A negative control (fibroblast protein with deletion of exons 20–23 from a patient with Menkes disease22) shows no detectable ATP7A. Lower panel: beta-actin control for loading.

(C) Immunocytochemistry for subcellular localization of P1386S ATP7A at 37°C in basal copper levels. Arrows show anti-ATP7A signal (red) with a perinuclear distribution consistent with trans Golgi localization in normal and P1386S fibroblasts. No antibody signal is evident in a del ex20–23 fibroblast cell. Cells were grown in media with normal copper concentration (0.5 μM) at 37°C and immunostained with an antibody against the carboxyl terminus of ATP7A. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

(D) Effect of temperature and copper concentration on the intracellular localization of ATP7A at 30°C. In 0.5 μM copper, both wild-type (a and c) and P1386S mutant (e and g) ATP7A (green in these panels) show extensive colocalization with the p230 trans Golgi marker (red in panels b and f) overlay in c and g. In 200 μM copper, the wild-type ATP7A shows trafficking out of the trans Golgi (i) and shows little localization with p230 (overlay in k). In contrast, the mutant P1386S did not show much movement out of the trans Golgi (m), and extensive perinuclear yellow remains, indicating colocalization with the p230 marker (o). Further demonstrating the difference in trafficking, cells indicated by the yellow arrows were enlarged and are shown in panels d, h, l, and p. Panels d and h clearly show the extensive areas of colocalization of both the wild-type and P1386S ATP7A in 0.5 μM copper. Panel l shows the complete trafficking of ATP7A out of the trans Golgi; only the red staining of p230 remains. Panel p shows extensive areas of yellow, indicating that much of the mutant ATP7A remains in the trans Golgi. Photographs were taken with a 63× objective lens on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope. The scale bar represents 40 μm.

Immunocytochemical and Biochemical Analyses and Trafficking of P1386S ATP7A Protein

In cultured mammalian cells, ATP7A localizes to the trans Golgi network in basal copper concentrations22,23 and relocates to small vesicles and the plasma membrane in cells exposed to elevated copper.23 Immunocytochemical analyses revealed correct trans Golgi localization of ATP7A in fibroblasts cultured at 37°C under basal copper conditions (Figure 4C, middle panel), whereas the steady-state fibroblast copper levels in P1386S fibroblast cell lines were intermediate between those in a normal control and a classical Menkes disease patient: fibroblasts from IV-2 and V-3 from family A contained 214.36 μg Cu/g dry weight ± 3.64 standard deviation (sd) and 118.08 μg Cu/g dry weight ± 6.97 SD, respectively, versus 84.12 ± 0.67 in the GM3652 normal cell line and 540.34 ± 19.45 SD in the del ex20–23 fibroblasts from a patient with Menkes disease22. Increased copper retention is characteristic of cultured fibroblasts from patients with Menkes disease and occipital horn syndrome,18 reflecting reduced capacity for copper exodus across the plasma membrane.

When we cultured P1386S fibroblasts at 30°C to assess the possibility of a conditional (temperature-sensitive) mutation,24,25 we observed impaired ATP7A trafficking in response to copper loading in these P1386S fibroblasts compared to normal fibroblasts (Figure 4D). Under basal copper conditions, the wild-type and mutant protein both showed extensive colocalization with the trans Golgi marker p230 (Figures 4D and 4Dh). After a 3 hr exposure to 200 μM copper, wild-type ATP7A was completely absent from the trans Golgi (Figure 4Dl), whereas the P1386S mutant protein remained substantially colocalized with the trans Golgi marker (Figure 4Dp). To confirm this observation, we scored 48 cells for the presence of ATP7A in the trans Golgi after copper exposure. This semiquantitative evaluation indicated that 24/27 (89%) P1386S cells retained ATP7A in the trans Golgi, as compared to 3/21 (14%) normal control cells (p < 0.0001). We also confirmed the presence of this trafficking abnormality in cultured T994I fibroblasts (Figure S1), which represents a delay in the expected movement of ATP7A-laden vesicles from the trans Golgi network to the plasma membrane after copper exposure.

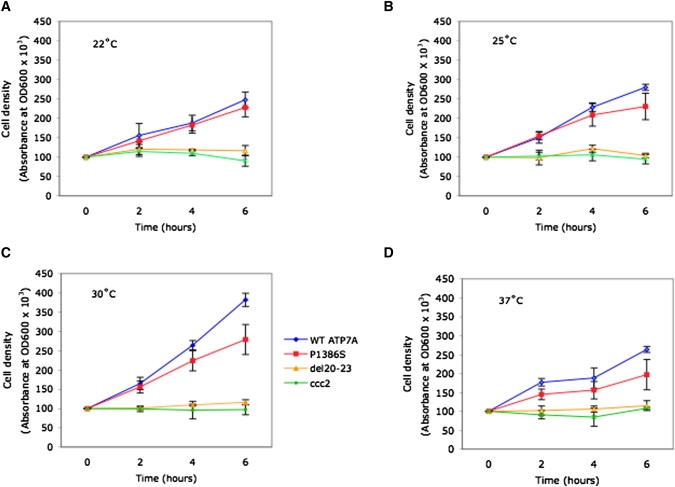

Yeast Complementation Studies

We also employed a yeast complementation assay19,22 to assess the capacity of the P1386S mutant allele to complement an S. cerevisiae copper-transport knockout, ccc2Δ. This assay measures the capacity of human ATP7A to replace the function normally performed by the ATP7A ortholog ccc2; specifically, this function is the delivery of copper to Fet3, a copper-containing protein required for high-affinity iron uptake.26 On copper- and iron-deficient solid media, the P1386S allele complemented ccc2Δ at 22°, 25°, 30°, and 37°C, whereas the ATP7A deletion allele, del ex20–23, did not (data not shown). To quantify the relative amount of residual copper-transport activity, we utilized a standard timed growth assay19,22,27–29 in copper- and iron-deficient liquid media at the four temperatures. The growth of ccc2Δ transformed with the P1386S allele was less than wild-type growth at all temperatures (Figure 5). At 30°C, the standard optimal temperature for yeast cell growth, the calculated copper-transport capacity of P1386S in ccc2Δ during exponential phase growth was 70% relative to that in ccc2Δ transformed by the wild-type ATP7A (Figure 5C). There was no further diminution in P1386S residual functional activity relative to the wild-type when the assay was performed at lower temperatures (22°C and 25°C, Figures 5A and 5B). As expected, ccc2Δ transformed with the del ex20–23 ATP7A allele (Figure 5, orange lines and triangles) grew poorly in the timed growth assay at all temperatures.

Figure 5.

Effects of Temperature on Yeast Complementation by P1386S ATP7A

For each of the temperatures noted ([A] 22°C, [B] 25°C, [C] 30°C, [D] 37°C), cell densities (OD600) of shaking liquid cultures were measured at 0, 2, 4, and 6 hr for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae copper transport mutant, ccc2Δ transformed with the wild-type (WT) ATP7A allele (blue), or ATP7A alleles harboring P1386S (red), a deletion of the ATP7A carboxyl-terminal four exons, del 20–23 (orange), and nontransformed ccc2Δ (green). Error bars denote ±1 standard deviation from the mean of quadruplicate OD600 measurements. The growth of ccc2Δ transformed with the P1386S allele was less than that of ccc2Δ transformed with the wild-type allele at all temperatures tested. Growth of these two yeast transformants was suboptimal at 22°C, 25°C, and 37°C compared to 30°C. At 30°C, P1386S complemented the ccc2Δ knockout strain at 70% of the wild-type rate. Residual copper transport was estimated from cell density at time points during exponential-phase growth (4 hr and 6 hr). Ccc2Δ transformed with the deletion allele (orange) and nontransformed ccc2Δ (green) grew poorly at all temperatures.

Discussion

Our findings reveal a third clinical phenotype associated with mutations in the ATP7A copper transporter gene, which was shown previously to cause Menkes disease14–16 and occipital horn syndrome.18 This new allelic variant involves progressive distal motor neuropathy with minimal or no sensory symptoms. Affected patients with the distal motor neuropathy discussed here do not manifest the severe infantile central neurological deficits observed in Menkes disease, the signs of autonomic dysfunction seen in occipital horn syndrome, the hair and connective-tissue abnormalities found in both conditions, or any of the clinical biochemical features of those well-characterized phenotypes.17–19,22 These findings highlight the phenotypic distinction between this isolated distal motor neuropathy and the syndromes previously associated with ATP7A mutations. By comparison of the molecular bases, Menkes disease is caused by profound loss-of-function mutations, including deletions, splice-site mutations at canonical positions, nonsense mutations, and missense mutations that affect a critical functional domain in ATP7A or induce misfolding,14–16,25,28,30 whereas occipital horn syndrome is associated with molecular defects that allow considerable residual copper transport, often via leaky splice-junction mutations involving noncanonical bases.18,19,30 In contrast, the missense mutations we describe here do not disrupt critical functional domains, disturb proper splicing, or cause reduced levels of ATP7A protein (Figure 4B). They occur in exons 15 (p.T994I) and 22 (p.P1386S), locations in which ATP7A missense mutations appear to be exceedingly rare.30 The phenomenon of late, often adult-onset, distal muscular atrophy implies that these mutations produce somewhat attenuated effects that require years to provoke pathological consequences. The aberrant ATP7A trafficking in P1386S and T994I fibroblasts, the copper-retention phenotype in P1386S fibroblasts that is intermediate between normal and classical Menkes disease, and the partial complementation of the ccc2Δ copper-transport knockout by the P1386S allele are all consistent with this hypothesis.

It is known that individuals with acquired copper deficiency due to excess zinc ingestion, malabsorption, gastric bypass surgery, or nephrotic syndrome can develop myeloneuropathy involving a profound sensory ataxia that improves or stabilizes in response to copper repletion.31–35 Signs of lower motor-neuron disease, including proximal and distal muscle weakness and bilateral foot drops, have also been reported in copper-deficient individuals.36 Taken together with these reports, our molecular, clinical, and biochemical findings suggest that motor neurons might be particularly sensitive to perturbations in copper homeostasis.

The precise nature of such perturbations remains to be elucidated. The abnormal trafficking of mutant ATP7A in fibroblasts at 30°C raises the possibility that these variants represent a new class of cold-sensitive mutations, although clinical evidence of thermal sensitivity is not overtly apparent in affected individuals from these families.8,9 A previously studied temperature-sensitive ATP7A missense mutation involved abnormal intracellular localization due to protein misfolding, which was ameliorated at a lower temperature (30°C).25 Because the P1386S and T994I trafficking defect is clearly not improved at lower temperatures (Figure 4D and S1), protein misfolding seems unlikely to explain the impact of these two mutations. The absence of dramatic temperature effects in the yeast complementation experiments is not surprising because proper trafficking is not required for metalation of Fet3p, the capacity for which is measured by this assay.26 Our results revealed a modest loss of copper-transport function (70% of wild-type) in this process for P1386S (Figure 5C). We speculate that reduced conformational flexibility in P1386S and T994I ATP7A impedes normal trafficking of the protein and impairs copper transport into the secretory pathway for incorporation into nascent cuproproteins.

Superoxide dismutase 1 (MIM 147450), cytochrome c oxidase (MIM 516030), dopamine-beta-hydroxylase (MIM 609312), and peptidyl-amidating monooxygenase (MIM 170270) are cuproenzymes highly relevant to neurological function.37 Although gain-of-function missense mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 are implicated in a familial form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis involving upper as well as lower motor-neuron degeneration,38 the ATP7A mutations we report presumably would reduce, rather than exaggerate, activity of this enzyme. Even slightly subnormal activities of certain copper enzymes might contribute to distal motor neuropathy. For example, chronic mild deficiency of cytochrome c oxidase, an inner mitochondrial membrane enzyme containing two subunits that bind copper,39 could gradually induce mitochondrial dysfunction in motor neurons.40

The requirement for ATP7A in normal axonal outgrowth and synaptogenesis has recently been recognized.41 Anterograde axonal ATP7A trafficking is induced by activation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor that binds glutamate and might be associated with synaptic release of copper.42 Thus, possible alternative mechanisms for the distal motor neuropathy in our patients include impaired axonal trafficking, glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity, and altered synaptic activity of ATP7A. Because the axons and synapses of distal motor neurons extend a considerable distance from their cell bodies in the spinal cord, we speculate that these neuronal elements might be autonomous from their cell bodies in terms of requirements for ATP7A.

The presence of intracellular protein aggregates has been described in many neurodegenerative diseases,37,38 and abnormal inclusions have been defined for heterogeneous forms of inherited distal motor neuropathy, typically identified when mutant proteins were overexpressed in mammalian cells.6,7,43–45 It will be useful to formally exclude or confirm such effects for the ATP7A mutations we report here.

The spectrum of genes implicated in the causation of distal motor neuropathy illustrates the diverse processes involved in motor neuron physiology.4–7,43,46 The identification of mutations in a gene essential to the homeostasis of trace metals reveals a new component in this system and further highlights the critical role of copper metabolism in neurodegeneration.37 Studies that explore and clarify the potential mechanisms suggested by our findings are warranted and might have relevance to other forms of motor-neuron disease, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Insights concerning the functions of ATP7A in motor neurons might lead to the development of rational treatments for this newly discovered form of X-linked distal motor neuropathy and other related disorders in which copper metabolism plays a previously under-appreciated role.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and family members for their participation in this study. We thank Rabia Chaudhry and Alison Blake for their assistance with cell cultures and Jose Centeno for fibroblast copper measurements. This work was supported by grants from the Motor Neuron Disease Research Institute of Australia, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the Intramural Research program of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the Methusalem project of the University of Antwerp, the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO-Flanders), the Medical Foundation Queen Elisabeth (GSKE), and the Interuniversity Attraction Poles program (P6/43) of the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO). J.B. and L.S. are supported by PhD fellowships of the FWO-Flanders and the University of Antwerp, respectively. We thank Professor David Handelsman for his useful constructive comments on the manuscript.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim

University of California, San Francisco Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

References

- 1.De Jonghe P., Timmerman V., Van Broeckhoven C. 2nd workshop of the European CMT consortium: 53rd ENMC international workshop on classification and diagnostic guidelines for Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2 (CMT2-HMSN II) and distal hereditary motor neuropathy (distal HMN-Spinal CMT) 26–28 September 1997, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul. Disord. 1998;8:426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding A.E. Inherited neuronal atrophy and degeneration predominantly of lower motor neurons. In: Dyck P.J., Thomas P.K., Griffin J.W., Low P.A., Poduslo J.F., editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1993. pp. 1051–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irobi-Devolder J. A molecular genetic update of inherited distal motor neuropathies. Verh. K. Acad. Geneeskd. Belg. 2008;70:25–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonellis A., Ellsworth R.E., Sambuughin N., Puls I., Abel A., Lee-Lin S.Q., Jordanova A., Kremensky I., Christodoulou K., Middleton L.T. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:1293–1299. doi: 10.1086/375039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evgrafov O.V., Mersiyanova I., Irobi J., Van Den Bosch B.L., Dierick I., Leung C.L., Schagina O., Verpoorten N., Van Impe K., Fedotov V. Mutant small heat-shock protein 27 causes axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:602–606. doi: 10.1038/ng1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irobi J., Van Impe K., Seeman P., Jordanova A., Dierick I., Verpoorten N., Michalik A., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V. Hot-spot residue in small heat-shock protein 22 causes distal motor neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:597–601. doi: 10.1038/ng1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Puls I., Oh S.J., Sumner C.J., Wallace K.E., Floeter M.K., Mann E.A., Kennedy W.R., Wendelschafer-Crabb G., Vortmeyer A., Powers R. Distal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy caused by dynactin mutation. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:687–694. doi: 10.1002/ana.20468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takata R.I., Speck Martins C.E., Passosbueno M.R., Abe K.T., Nishimura A.L., Da Silva M.D., Monteiro A., Jr., Lima M.I., Kok F., Zatz M. A new locus for recessive distal spinal muscular atrophy at Xq13.1-q21. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:224–229. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennerson M., Nicholson G., Kowalski B., Krajewski K., El-Khechen D., Feely S., Chu S., Shy M., Garbern J. X-linked distal hereditary motor neuropathy maps to the DSMAX locus on chromosome Xq13.1-q21. Neurology. 2009;72:246–252. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000339483.86094.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Bie P., Muller P., Wijmenga C., Klomp L.W. Molecular pathogenesis of Wilson and Menkes disease: Correlation of mutations with molecular defects and disease phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:673–688. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.052746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Fontaine S., Mercer J.F. Trafficking of the copper-ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B: Role in copper homeostasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2007;463:149–167. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lutsenko S., Gupta A., Burkhead J.L., Zuzel V. Cellular multitasking: The dual role of human Cu-ATPases in cofactor delivery and intracellular copper balance. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;476:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veldhuis N.A., Gaeth A.P., Pearson R.B., Gabriel K., Camakaris J. The multi-layered regulation of copper translocating P-type ATPases. Biometals. 2009;22:177–190. doi: 10.1007/s10534-008-9183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chelly J., Tumer Z., Tonnesen T., Petterson A., Ishikawa-Brush Y., Tommerup N., Horn N., Monaco A.P. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease that encodes a potential heavy metal binding protein. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:14–19. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercer J.F., Livingston J., Hall B., Paynter J.A., Begy C., Chandrasekharappa S., Lockhart P., Grimes A., Bhave M., Siemieniak D. Isolation of a partial candidate gene for Menkes disease by positional cloning. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:20–25. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vulpe C., Levinson B., Whitney S., Packman S., Gitschier J. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease and evidence that it encodes a copper-transporting ATPase. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaler S.G. Menkes disease. Adv. Pediatr. 1994;41:263–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaler S.G., Gallo L.K., Proud V.K., Percy A.K., Mark Y., Segal N.A., Goldstein D.S., Holmes C.S., Gahl W.A. Occipital horn syndrome and a mild Menkes phenotype associated with splice site mutations at the MNK locus. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang J., Robertson S., Lem K.E., Godwin S.C., Kaler S.G. Functional copper transport explains neurologic sparing in occipital horn syndrome. Genet. Med. 2006;8:711–718. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000245578.94312.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lem K.E., Brinster L.R., Tjurmina O., Lizak M., Lal S., Centeno J.A., Liu P.C., Godwin S.C., Kaler S.G. Safety of intracerebroventricular copper histidine in adult rats. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2007;91:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ke B.X., Llanos R.M., Wright M., Deal Y., Mercer J.F. Alteration of copper physiology in mice overexpressing the human Menkes protein ATP7A. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;290:R1460–R1467. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00806.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaler S.G., Holmes C.S., Goldstein D.S., Tang J., Godwin S.C., Donsante A., Liew C.J., Sato S., Patronas N. Neonatal diagnosis and treatment of Menkes disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:605–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petris M.J., Mercer J.F., Culvenor J.G., Lockhart P., Gleeson P.A., Camakaris J. Ligand-regulated transport of the Menkes copper P-type ATPase efflux pump from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane: a novel mechanism of regulated trafficking. EMBO J. 1996;15:6084–6095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payne A.S., Kelly E.J., Gitlin J.D. Functional expression of the Wilson disease protein reveals mislocalization and impaired copper-dependent trafficking of the common H1069Q mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:10854–10859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim B.E., Smith K., Meagher C.K., Petris M.J. A conditional mutation affecting localization of the Menkes disease copper ATPase. Suppression by copper supplementation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:44079–44084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Askwith C.C., de Silva D., Kaplan J. Molecular biology of iron acquisition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 1996;20:27–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donsante A., Tang J., Godwin S.C., Holmes C.S., Goldstein D.S., Bassuk A., Kaler S.G. Differences in ATP7A gene expression underlie intrafamilial variability in Menkes disease/occipital horn syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:492–497. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.050013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang J., Donsante A., Desai V., Patronas N., Kaler S.G. Clinical outcomes in Menkes disease patients with a copper-responsive ATP7A mutation, G727R. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2008;95:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaler S.G., Tang J., Donsante A., Kaneski C.R. Translational read-through of a nonsense mutation in ATP7A impacts treatment outcome in Menkes disease. Ann. Neurol. 2009;65:108–113. doi: 10.1002/ana.21576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsi G., Cox D.W. A comparison of the mutation spectra of Menkes disease and Wilson disease. Hum. Genet. 2004;114:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-1045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodman B.P., Bosch E.P., Ross M.A., Hoffman-Snyder C., Dodick D.D., Smith B.E. Clinical and electrodiagnostic findings in copper deficiency myeloneuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2009;80:524–527. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelkar P., Chang S., Muley S.A. Response to oral supplementation in copper deficiency myeloneuropathy. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2008;10:1–3. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181828cf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar N., Ahlskog J.E., Klein C.J., Port J.D. Imaging features of copper deficiency myelopathy: A study of 25 cases. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:78–83. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-0016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spain R.I., Leist T.P., De Sousa E.A. When metals compete: a case of copper-deficiency myeloneuropathy and anemia. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009;5:106–111. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zara G., Grassivaro F., Brocadello F., Manara R., Pesenti F.F. Case of sensory ataxic ganglionopathy-myelopathy in copper deficiency. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;277:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weihl C.C., Lopate G. Motor neuron disease associated with copper deficiency. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:789–793. doi: 10.1002/mus.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desai V., Kaler S.G. Role of copper in human neurological disorders. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008;88:855S–858S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.3.855S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruijn L.I., Miller T.M., Cleveland D.W. Unraveling the mechanisms involved in motor neuron degeneration in ALS. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:723–749. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoubridge E.A. Cytochrome c oxidase deficiency. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;106:46–52. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Comi G.P., Bordoni A., Salani S., Franceschina L., Sciacco M., Prelle A., Fortunato F., Zeviani M., Napoli L., Bresolin N. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I microdeletion in a patient with motor neuron disease. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:110–116. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El Meskini R., Crabtree K.L., Cline L.B., Mains R.E., Eipper B.A., Ronnett G.V. ATP7A (Menkes protein) functions in axonal targeting and synaptogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2007;34:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlief M.L., Craig A.M., Gitlin J.D. NMDA receptor activation mediates copper homeostasis in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:239–246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Windpassinger C., Auer-Grumbach M., Irobi J., Patel H., Petek E., Horl G., Malli R., Reed J.A., Dierick I., Verpoorten N. Heterozygous missense mutations in BSCL2 are associated with distal hereditary motor neuropathy and Silver syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:271–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy J.R., Sumner C.J., Caviston J.P., Tokito M.K., Ranganathan S., Ligon L.A., Wallace K.E., LaMonte B.H., Harmison G.G., Puls I. A motor neuron disease-associated mutation in p150Glued perturbs dynactin function and induces protein aggregation. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:733–745. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maystadt I., Rezsohazy R., Barkats M., Duque S., Vannuffel P., Remacle S., Lambert B., Najimi M., Sokal E., Munnich A. The nuclear factor kappaB-activator gene PLEKHG5 is mutated in a form of autosomal recessive lower motor neuron disease with childhood onset. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:67–76. doi: 10.1086/518900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dion P.A., Daoud H., Rouleau G.A. Genetics of motor neuron disorders: new insights into pathogenic mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:769–782. doi: 10.1038/nrg2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daube J.R., Rubin D.I. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2009. Clinical Neurophysiology. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.