Abstract

Objective: To find new protein biomarkers for the detection and evaluation of liver injury and to analyze the relationship between such proteins and disease progression in concanavalin A (Con A)-induced hepatitis. Methods: Twenty-five mice were randomly divided into five groups: an untreated group, a control group injected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and groups with Con A-induced hepatitis evaluated at 1, 3 and 6 h. Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) and mass spectrometry (MS) were used to identify differences in protein expression among groups. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed to verify the results. Results: In mice with Con A-induced hepatitis, expression levels of four proteins were increased: RIKEN, fructose bisphosphatase 1 (fbp1), ketohexokinase (khk), and Chain A of class pi glutathione S-transferase. Changes in fbp1 and khk were confirmed by qRT-PCR. Conclusion: Levels of two proteins, fbp1 and khk, are clearly up-regulated in mice with Con A-induced hepatitis.

Keywords: Concanavalin A (Con A), Liver injury, Protein, Two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE)

1. Introduction

Toxic liver disease is a worldwide health problem. The mechanisms that induce this disease are highly complex and involve numerous metabolic pathways and substances inside and outside the cells that respond to the toxin stimulus. The importance of this disease is demonstrated by the recent establishment of the liver toxicity biomarker study (LTBS) (McBurney et al., 2009). When mice are treated with concanavalin A (Con A), lymphokines are released from lymphocytes and other mononuclear cells (Kelso and Gough, 1987) and there is a rapid inflammatory alteration of the liver tissue, including obvious infiltration of neutrophils, macrophages and T cells, and a significant simultaneous increase in the level of transaminases in the peripheral blood. The murine model of Con A-induced hepatitis was first established by Tiegs et al. (1992) to study the expression of hemopoietic growth factor genes of T lymphocytes, and in recent years has been widely used as a model of toxic liver disease.

Since two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) was developed by O′Farrell (1975), it has been an important method for protein separation (Dominguez et al., 2007). 2-DE combined with mass spectrometry (MS) has been widely applied to the analysis of levels of protein expression and comparisons between diseased and normal individuals using this method are used for biomarker discovery (He et al., 2003). Here we used 2-DE/MS to evaluate samples from mice with Con A-induced hepatitis and compared them to those from normal mice to analyze changes in protein expression resulting from liver toxicity.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatments

We purchased twenty-five male BALB/c mice (18–20 g) from Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences and kept them for at least 1 week at 22 °C and 55% relative humidity in a 12 h day/night rhythm. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All experiments were conducted according to our institutional rules on animal experiments. Mice were randomly divided into five groups. One group was untreated; one group was injected with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). For the other three groups, mice were given Con A dissolved in pyrogen-free saline (20 mg/kg) via a tail vein injection. Mice were sacrificed at 1, 3 and 6 h after injection of Con A, and liver tissue and serum were collected at the time of sacrifice.

2.2. Histochemistry

Liver tissue was fixed with 10% (w/v) formalin/PBS and then stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H & E) according to standard protocols.

2.3. Analysis of alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities

We quantified liver injury by measuring plasma activities of ALT, AST, and LDH in the clinical laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University using standard protocols.

2.4. Protein sample preparation and 2-DE

Liver tissue was prepared as described by Henkel et al. (2006). Protein (200 μg per sample) was analyzed from each of the five mice in each group. We used 24-cm immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips (pH 3–10 non-linear) and the IPGphor isoelectric focusing (IEF) system (GE, UK) for the first dimension and 200 μg protein was loaded. The second dimension of electrophoresis was a vertical 12.5% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The process of isoelectric focusing, SDS-PAGE, silver staining and imaging of the 2-D gels was carried out as described in Yu et al. (2007). Samples from each mouse were analyzed three to five times. Selected protein spots from correlation analysis (van Belle et al., 2006) were excised from gels and placed in Eppendorf tubes and digested as described by Wilm et al. (1996).

2.5. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis of tryptic peptides

Mass analysis was performed using a Bruker-Daltonics AutoFlex TOF-TOF LIFT Mass Spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). MS spectra were acquired in reflector mode. The MALDI spectra were averaged over 50 laser shots. We used a standard peptide mixture [hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA)] to calibrate all mass spectra externally and trypsin auto-digestion peaks for internal calibration.

2.6. Identification of differentially expressed proteins

We used peptide mass fingerprints obtained by the MALDI-TOF MS to search non-redundant protein database (NCBInr) using Mascot software. The parameters were peptide mass between 1 000 and 3 000 U and carbamidomethyl and oxidation allowed for modifications. One missed cleavage site was allowed and mass accuracy was ±1 U. The species was restricted to Mus musculus. The criteria for positive protein identification were: (1) the protein score was −10×logP, where P is the probability that the observed match is a random event; protein scores greater than 64 were significant (P<0.05) and (2) 100×10−6 or better mass accuracy was required.

2.7. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

To verify the result of 2-DE, we performed qRT-PCR to measure the mRNA expression of related proteins. We isolated mRNA from hepatic cells according to standard protocols and converted it to complementary DNA (cDNA) as described by Zhang et al. (2004). The SYBR green assay (ABI, USA) was carried out as per the manufacturer’s protocols using an ABI 7900 thermocycler. qRT-PCR was performed to quantify the amplification of target cDNA using β-actin expression as an internal control. The parameters for qRT-PCR were as described by Farago et al. (2008). The following primers were used: β-actin sense, 5′-AACAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCAC-3′; β-actin antisense, 5′-CGTTGACATCCGTAAAGACC-3′; RIKEN sense, 5′-GGTTGCTTGGGCTGTT-3′; RIKEN antisense, 5′-GTCCACGCTCATCACG-3′; fructose bisphosphatase 1 (fbp1) sense, 5′-CTGCGGCTGCTGTATG-3′; fbp1 antisense, 5′-TCGGTGGGAACGATGTCT-3′; ketohexokinase (khk) sense, 5′-GCTATGGTGAGGTGGTGTT-3′; khk antisense, 5′-GTGGGAAGGCATCTGAGTG-3′.

2.8. Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance (P<0.05) was determined using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post-testing was performed using the Bonferroni method.

3. Results

3.1. Con A-induced liver injury

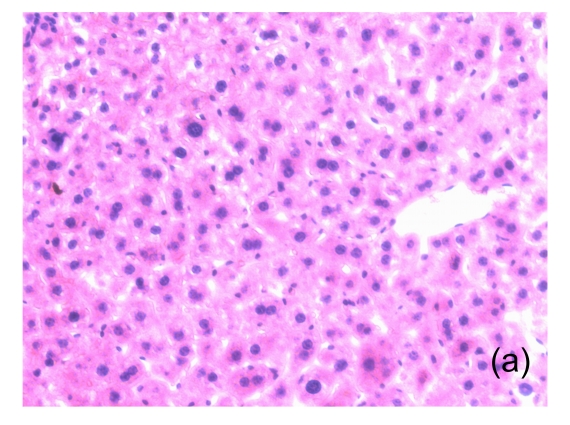

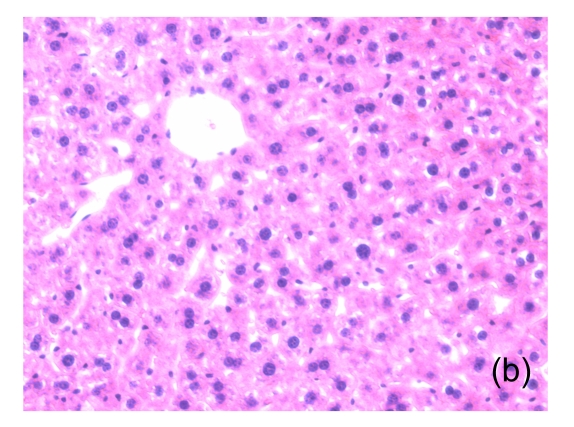

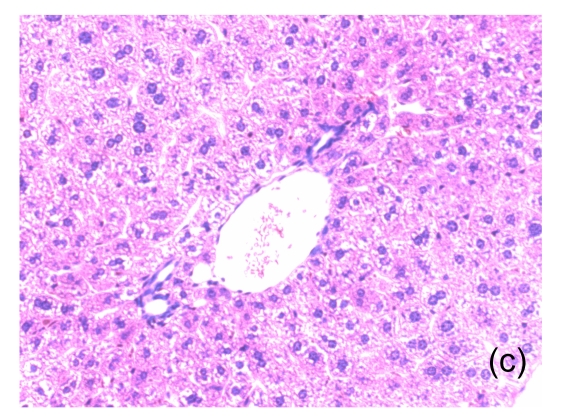

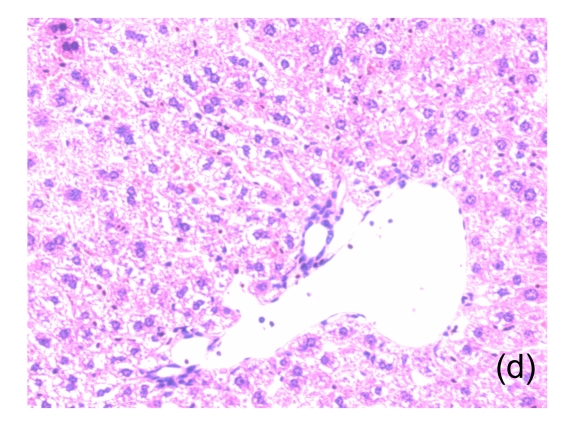

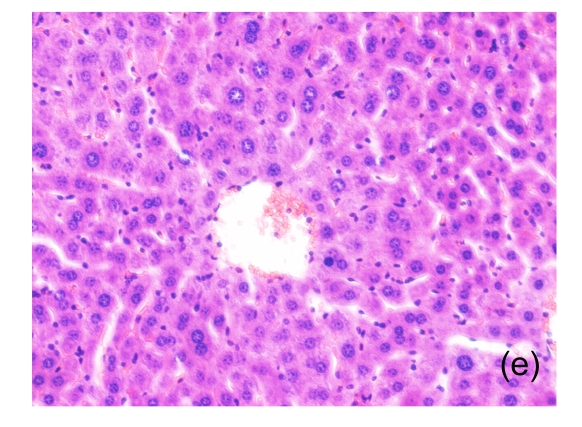

Acute hepatitis was induced by intravenous injection with Con A via a tail vein. Mice were sacrificed at 1, 3, and 6 h after injection, and serum and liver tissue were collected for biochemical and histological evaluation. No deaths occurred in any groups due to treatment. Progressive elevation of biochemical markers ALT [from (64.40±5.36) U/L at 1 h to (1 262.0±1 014.50) U/L at 6 h], AST [from (202.20±64.89) U/L at 1 h to (900.20±730.99) U/L at 6 h], and LDH [from (978.60±151.83) U/L at 1 h to (4 046.40±2 245.91) U/L at 6 h] was observed in the Con A-treated animals, whereas no significant alterations were found in control animals (Table 1). Histological analysis confirmed that the development of liver injury paralleled increases in levels of these biochemical markers (Fig. 1). This histological alteration was liver-specific and no obvious changes were observed in liver tissues of control animals (data not shown).

Table 1.

Dose dependence of Con A-induced liver injury in mice

| Group | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | LDH (U/L) | Number of mice |

| Untreated | 38.20±1.64 | 85.33±2.86 | 832.40±66.92 | 5 |

| PBS | 36.20±1.92 | 85.09±2.73 | 846.80±48.82 | 5 |

| Con A, 1 h | 64.40±5.36 | 202.20±64.89* | 978.60±151.83 | 5 |

| Con A, 3 h | 1 131.40±691.14* | 266.00±124.97* | 3 308.80±1 278.87* | 5 |

| Con A, 6 h | 1 262.00±1 014.50* | 900.20±730.99* | 4 046.40±2 245.91* | 5 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD

P≤0.05 vs. untreated and PBS control groups

Multiple comparisons were collected using the Bonferroni method

Fig. 1.

Microscopic appearance of the liver in mice representative of each group

(a) Untreated mice; (b) PBS-treated mice; (c) 1 h after injecting Con A intravenously; (d) 3 h after injecting Con A intravenously (note a small amount of hepatocyte swelling); (e) 6 h after injecting Con A intravenously (note severe hepatocyte swelling and necrosis)

3.2. Differential proteome analysis of 2-DE maps

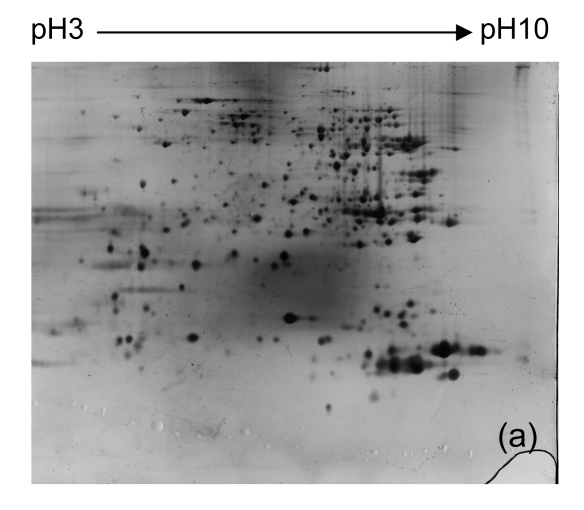

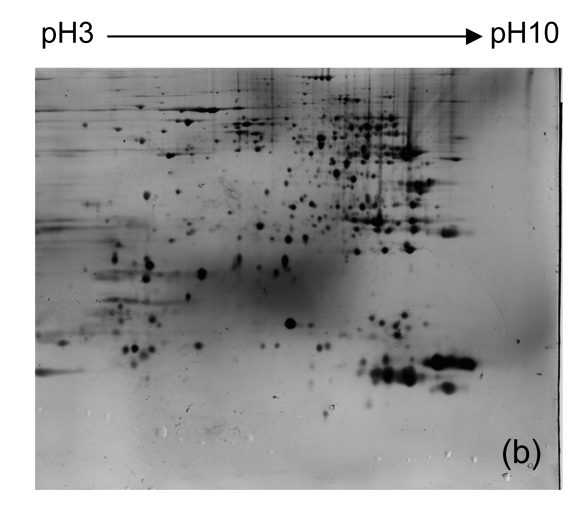

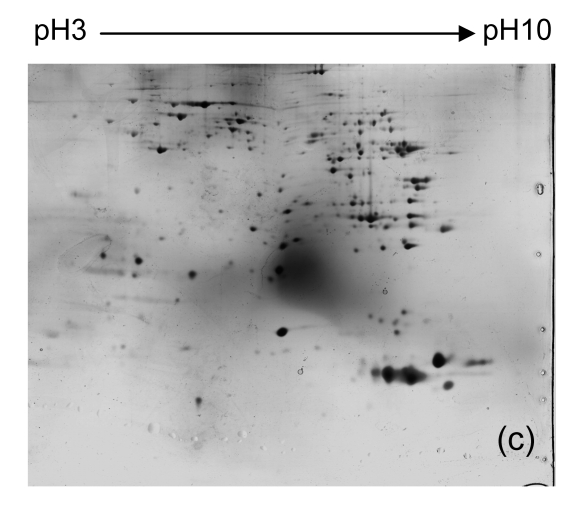

To identify proteins with differential expression in the liver between Con A-treated and control tissues, we isolated protein from livers of all mice from each group. We then used 2-DE and silver staining to separate and visualize proteins. Representative 2-DE patterns are shown in Fig. 2. Nearly 500 proteins spots were obtained in the range of M r 14 400–94 000, and pI 3–10.

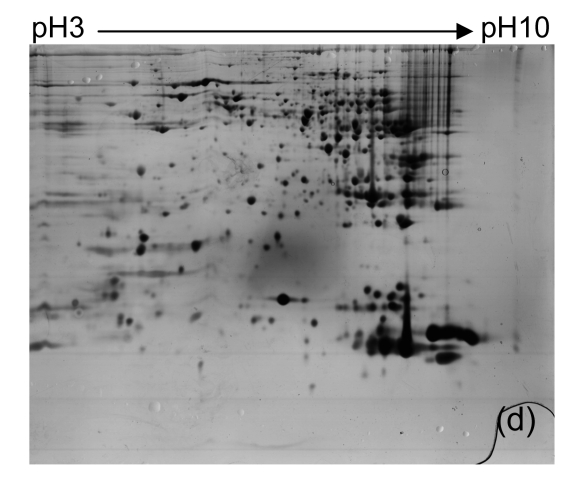

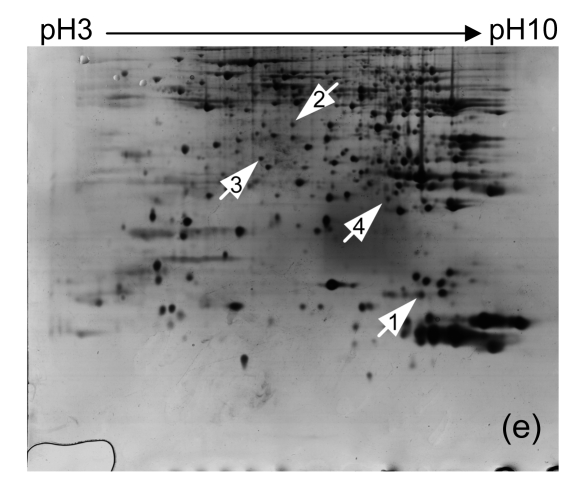

Fig. 2.

Representative 2-DE maps of liver proteins from samples from each group of mice. In the first dimension of electrophoresis, 200 μg protein was loaded on strips (240 mm, pH 3–10 non-linear); the second dimension of electrophoresis was a vertical 12.5% (w/v) SDS-PAGE

(a) Untreated controls; (b) PBS controls; (c)–(e) 1, 3, and 6 h after injecting Con A intravenously, respectively

3.3. Protein identification by MALDI-TOF MS

Four distinct protein spots (Fig. 2) were excised from gels. The intensity of each of these spots was up-regulated in liver tissue collected 6 h after Con A treatment when compared to controls. The proteins in these spots were digested with trypsin in the gel, and were eluted and analyzed using MALDI-TOF MS. The proteins were identified by comparison to data in the NCBInr using Mascot software (Table 2).

Table 2.

Identification of proteins with up-regulated expression after Con A treatment

| Spot number | Accession | Mr | Score | Peptide matched | Sequence covered (%) | Protein description |

| 1 | gi|17118017 | 14 228 | 93 | 6/12 | 43 | RIKEN |

| 2 | gi|9506589 | 37 288 | 111 | 8/10 | 20 | Fructose bisphosphatase 1 (fbp1) |

| 3 | gi|31982229 | 33 290 | 74 | 7/26 | 27 | Ketohexokinase (khk) |

| 4 | gi|576133 | 23 634 | 84 | 7/10 | 47 | Chain A of class pi glutathione S-transferase |

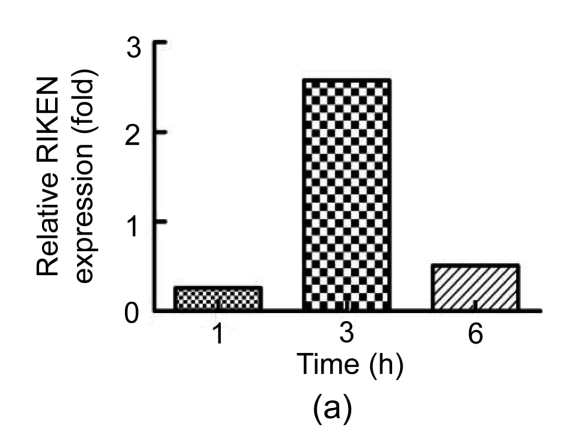

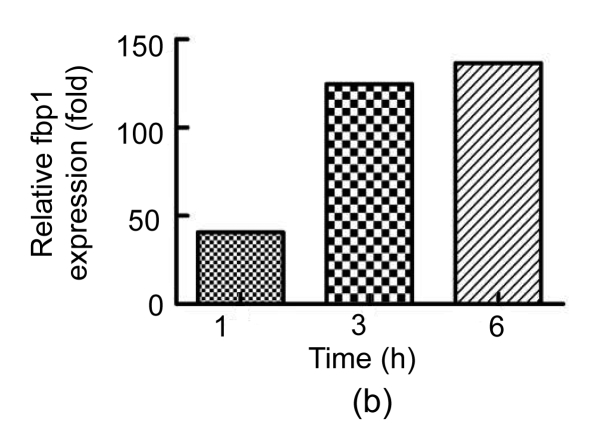

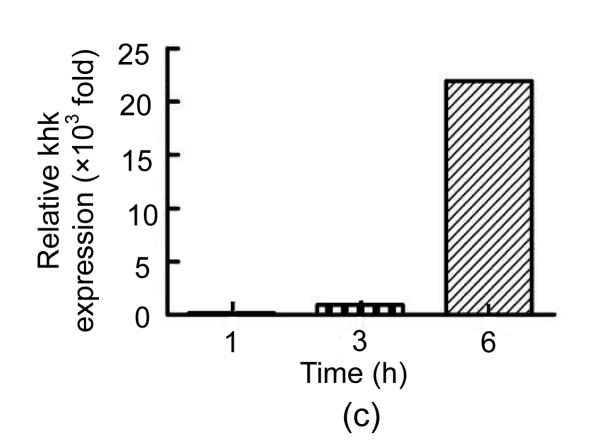

3.4. qRT-PCR analysis of selected proteins

To validate the results from 2-DE, we used qRT-PCR to measure the mRNA levels of the proteins identified. We were unable to find an accurate gene sequence for Chain A of the class pi glutathione S-transferase, so levels of only three of the four proteins were evaluated (Fig. 3). The untreated group’s ΔC t was used as a reference and calculated as described by Yuan et al. (2006). There was no significant difference between the levels of these mRNAs in the mice treated with PBS and untreated mice. Although protein levels were elevated in Con A-treated mice, the levels of RIKEN mRNA in Con A-treated mice were reduced by about 74% and 49% at 1 and 6 h, respectively, compared to those in untreated controls. The levels of fbp1 and khk mRNA were increased in Con A-injected mice compared to those in untreated controls. Thus, the mRNA expression of fbp1 and khk was consistent with the 2-DE analysis of protein levels.

Fig. 3.

qRT-PCR analysis of selected proteins

Relative expression of (a) RIKEN, (b) fbp1, and (c) khk at 1, 3 and 6 h after Con A injection compared with the levels in untreated controls

4. Discussion

In recent years, proteomic technologies have made an impact on biomedical research, especially on biomarker discovery. Proteins are responsible for carrying out biological functions and recent studies have shown that levels of protein and mRNA expression are not always correlated (Bodzon-Kulakowska et al., 2007). Therefore, it is of great interest to study the expression of proteins, which may be altered by different disease processes.

In this study, we established an acute hepatitis model by injecting Con A intravenously into mice. We then quantitatively analyzed the expression of liver proteins in Con A-treated and untreated mice. McBurney et al. (2009) searched for biomarkers for phase I of drug-induced liver injury; protein levels were evaluated 3 and 28 d after dosing. We chose time points at 1, 3 and 6 h after Con A injection because Tiegs et al. (1992) showed that liver injury was observed only 8 h after Con A treatment of male BALB/c mice. Thus, our analysis revealed changes in protein levels in the acute phase of liver injury. We confirmed the establishment of the model by biochemical testing and histological examination at each of the three time points. The liver protein profiles of the Con A-induced injury groups were compared to those of the corresponding controls by 2-DE, and proteins with altered expression were identified by MS. Four proteins were up-regulated by Con A treatment: RIKEN, fbp1, khk, and Chain A of class pi glutathione S-transferase.

Fbp1 belongs to the protein family of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatases (Horecker et al., 1975). It catalyzes the fructose-1,6-biphosphate hydrolysis into fructose-6-phosphate and plays a critical role in gluconeogenesis. Duncan et al. (1994) demonstrated that fbp1 is a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that activates the far upstream element of c-Myc. Cuesta et al. (2006) found that fructose-1,6-bisphosphate prevents endotoxemia and liver injury induced by D-galactosamine in rats by inhibiting macrophage activation. They also found that exogenous fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase has anti-histaminic and anti-inflammatory action through its function as a K+ channel modulator. We hypothesize that the expression of fbp1 may be increased to a level above the threshold for its anti-inflammatory action in response to Con A challenge. Further research is needed to prove this hypothesis.

In dietary fructose metabolism, the first step is catalysis of the phosphorylation of fructose to fructose-1-phosphate (F1P) (Hwa et al., 2006). Khk plays an important role in this process. In higher eukaryotes, khk is believed to function as a dimer and K+ and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) are required for activity. In humans, a benign inborn error of metabolism caused by fructosuria is called hepatic khk deficiency (Bonthron et al., 1994). Wang et al. (1980) found that phosphofructokinase activity is increased in mouse spleen lymphocytes in culture 8 h after Con A stimulation. We found similar increases at 6 h after Con A injection but not at 3 h. This change in khk levels may be related to the mechanism of anti-inflammation. The role that Chain A of class pi glutathione S-transferase might play in liver toxicity is not clear. The 3D structure has been determined and its inhibitors may reduce inflammation (Párraga et al., 1998; García-Sáez et al., 1994). We noted that chain A was also up-regulated in the PBS group and thus it may be induced by non-specific stress.

The changes in fbp1 and khk protein levels were correlated with up-regulation in mRNA levels as shown by qRT-PCR in Con A-treated mice. However, RIKEN mRNA levels were decreased rather than increased in Con A-treated mice. We were unable to evaluate mRNA levels for glutathione S-transferase as the sequence has not yet been clearly established. Puppala et al. (2006) used a mouse model to study gallbladder disease and found clear correlations between mRNA and protein levels. Our qRT-PCR and 2-DE results were not so consistent. It may be that the expression of protein and mRNA is not necessarily correlated (Bodzon-Kulakowska et al., 2007).

In conclusion, this study provided information regarding several proteins up-regulated soon after induction of hepatitis in a mouse model. Up-regulation of the expression of these four proteins may be due to a direct cytopathic effect of Con A or a Con A-induced inflammatory response. Further analysis of these proteins in cell culture experiments will be required to determine their role in liver toxicity induced by Con A.

5. Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Shu-ping Li (the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China) for his help with 2D gel electrophoresis analysis and Dr. Jie Li and Dr. Dong-jiu Zhao (the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China) for advice on the discussion section. We also thank the researchers in the clinical laboratory of the First Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University for their assistance with biochemical tests.

Footnotes

Project (No. 20082X10002-007) supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

References

- 1.Bodzon-Kulakowska A, Bierczynska-Krzysik A, Dylag T, Drabik A, Suder P, Noga M, Jarzebinska J, Silberring J. Methods for samples preparation in proteomic research. J Chromatogr B. 2007;849(1-2):1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonthron DT, Brady N, Donaldson IA, Steinmann B. Molecular basis of essential fructosuria: molecular cloning and mutational analysis of human ketohexokinase (fructokinase) Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3(9):1627–1631. doi: 10.1093/hmg/3.9.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuesta E, Boada J, Calafell R, Perales JC, Roig T, Bermudez J. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate prevented endotoxemia, macrophage activation, and liver injury induced by D-galactosamine in rats. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):807–814. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000202016.60856.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominguez DC, Lopes R, Torres ML. Proteomics technology. Clin Lab Sci. 2007;20(4):239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan R, Bazar L, Michelotti G, Tomonaga T, Krutzsch H, Avigan M, Levens D. A sequence-specific, single-strand binding protein activates the far upstream element of c-myc and defines a new DNA-binding motif. Genes Dev. 1994;8(4):465–480. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.4.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farago N, Kocsis GF, Feher LZ, Csont T, Hackler LJr, Varga-Orvos Z, Csonka C, Kelemen JZ, Ferdinandy P, Puskas LG. Gene and protein expression changes in response to normoxic perfusion in mouse hearts. J Pharmacol Toxicol Meth. 2008;57(2):145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Sáez I, Párraga A, Phillips MF, Mantle TJ, Coll M. Molecular structure at 1.8 A of mouse liver class pi glutathione S-transferase complexed with S-(p-nitrobenzyl) glutathione and other inhibitors. J Mol Biol. 1994;237(3):298–314. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He QY, Lau GK, Zhou Y, Yuen ST, Lin MC, Kung HF, Chiu JF. Serum biomarkers of hepatitis B virus infected liver inflammation: a proteomic study. Proteomics. 2003;3(5):666–674. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Henkel C, Roderfeld M, Weiskirchen R, Berres ML, Hillebrandt S, Lammert F, Meyer HE, Stühler K, Graf J, Roeb E. Changes of the hepatic proteome in murine models for toxically induced fibrogenesis and sclerosing cholangitis. Proteomics. 2006;6(24):6538–6548. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horecker BL, Melloni E, Pontremoli S. Fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase: properties of the neutral enzyme and its modification by proteolytic enzymes. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1975;42:193–226. doi: 10.1002/9780470122877.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwa JS, Kim HJ, Goo BM, Park HJ, Kim CW, Chung KH, Park HC, Chang SH, Kim YW, Kim DR, et al. The expression of ketohexokinase is diminished in human clear cell type of renal cell carcinoma. Proteomics. 2006;6(3):1077–1084. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelso A, Gough NM. Expression of Hemopoietic Growth Factor Genes in Murine T Lymphocytes. In: Webb DR, Goeddel DV, editors. Lymphokines. Vol. 13. London: Academic Press Inc; 1987. pp. 209–238. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBurney RN, Hines WM, von Tungeln LS, Schnackenberg LK, Beger RD, Moland CL, Han T, Fuscoe JC, Chang CW, Chen JJ, et al. The liver toxicity biomarker study: phase I design and preliminary results. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37(1):52–64. doi: 10.1177/0192623308329287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O′Farrell PH. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(10):4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Párraga A, García-Sáez I, Walsh SB, Mantle TJ, Coll M. The three-dimensional structure of a class-pi glutathione S-transferase complexed with glutathione: the active-site hydration provides insights into the reaction mechanism. Biochem J. 1998;333(Pt 3):811–816. doi: 10.1042/bj3330811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puppala S, Dodd GD, Fowler S, Arya R, Schneider J, Farook VS, Granato R, Dyer TD, Almasy L, Jenkinson CP, et al. A genomewide search finds major susceptibility loci for gallbladder disease on chromosome 1 in Mexican Americans. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(3):377–392. doi: 10.1086/500274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tiegs C, Hentschel J, Wendel A. A cell-dependent experimental liver injury in mice inducible by concanavalin A. J Clin Invest. 1992;90(1):196–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI115836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Belle W, Ånensen N, Haaland I, Bruserud Ø, Høgda KA, Gjertsen BT. Correlation analysis of two-dimensional gel electrophoretic protein patterns and biological variables. BMC Bioinf. 2006;7(1):198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T, Foker JE, Tsai MY. The shift of an increase in phosphofructokinase activity from protein synthesis-dependent to -independent mode during concanavalin A induced lymphocyte proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;95(1):13–19. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(80)90697-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilm M, Shevchenko A, Houthaeve T, Breit S, Schweigerer L, Fotsis T, Mann M. Femtomole sequencing of proteins from polyacrylamide gels by nano-electrospray mass spectrometry. Nature. 1996;379(6564):466–469. doi: 10.1038/379466a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu M, Wang XX, Zhang FR, Shang YP, Du YX, Chen HJ, Chen JZ. Proteomic analysis of the serum in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B. 2007;8(4):221–227. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan JS, Reed A, Chen F, Stewart CNJr. Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinf. 2006;7(1):85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang AS, Xiong S, Tsukamoto H, Enns CA. Localization of iron metabolism-related mRNAs in rat liver indicate that HFE is expressed predominantly in hepatocytes. Blood. 2004;103(4):1509–1514. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]