Abstract

Purpose

To generate and evaluate a modular recombinant transporter (MRT) for targeting 211At to cancer cells overexpressing the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

Methods and Materials

The MRT was produced with four functional modules: (1) human epidermal growth factor as the internalizable ligand, (2) the optimized nuclear localization sequence of simian vacuolating virus 40 (SV40) large T-antigen, (3) a translocation domain of diphtheria toxin as an endosomolytic module, and (4) the Escherichia coli hemoglobin-like protein (HMP) as a carrier module. MRT was labeled using N-succinimidyl 3-[211At]astato-5-guanidinomethylbenzoate (SAGMB), its 125I analogue SGMIB, or with 131I using Iodogen. Binding, internalization, and clonogenic assays were performed with EGFR-expressing A431, D247 MG, and U87MG.wtEGFR human cancer cell lines.

Results

The affinity of SGMIB-MRT binding to A431 cells, determined by Scatchard analysis, was 22 nM, comparable to that measured before labeling. The binding of SGMIB-MRT and its internalization by A431 cancer cells was 96% and 99% EGFR specific, respectively. Paired label assays demonstrated that compared with Iodogen-labeled MRT, SGMIB-MRT and SAGMB-MRT exhibited more than threefold greater peak levels and durations of intracellular retention of activity. SAGMB-MRT was 10–20 times more cytotoxic than [211At]astatide for all three cell lines.

Conclusion

The results of this study have demonstrated the initial proof of principle for the MRT approach for designing targeted α-particle emitting radiotherapeutic agents. The high cytotoxicity of SAGMB-MRT for cancer cells overexpressing EGFR suggests that this 211At-labeled conjugate has promise for the treatment of malignancies, such as glioma, which overexpress this receptor.

Keywords: Modular recombinant transporters, Epidermal growth factor receptor, 211At, Radionuclide therapy, Nuclear targeting

INTRODUCTION

Although the mechanisms through which radiation can interfere with cellular proliferation are complex, strong empirical evidence has shown that with both conventional and high linear energy transfer (LET) radiation, increasing the energy deposition in the cell nucleus results in a decreased cell survival fraction (1, 2). Strategies that shift the site of radionuclide decay from the cell surface to the nucleus are advantageous for two reasons. First, they increase the geometric probability (solid angle) that the nucleus will be traversed by the radiation. Even with the multicellular range β-emitter 131I, dosimetry calculations and in vitro experiments have shown that shifting the site of decay from the cell membrane to the cytoplasmic vesicles near the nucleus increases the cell nucleus radiation dose and cytotoxicity by a factor of two to three (3). Second, radiation in the subcellular range cannot be effective unless the site of decay is within the range of the cell nucleus. For example, if an α-particle emitter can be localized in the cell nucleus, one can also exploit the cytotoxic potential of the α-particle recoil nucleus created during α-decay, which has a subcellular tissue range of <100 nm and an LET of about 10 times greater than that of the α-particle itself (4, 5). When located outside the cell, α-particle recoil nuclei are not cytotoxic. The radiation dose deposited in the cell nucleus from radionuclides decaying in various cellular sites has been calculated for different cell geometries, and the results have indicated a significant increase in the dose to the cell nucleus for sources located within the cell nucleus (6).

We have confirmed the predicted exquisite cytotoxicity of 211At when localized in the cell nucleus in studies with 5-[211At]astato-2′-deoxyuridine (AUdR) (7, 8). Effective killing of tumor cells, including a human glioma line, could be achieved in vitro after only about one to three α-particle hits per cell. This labeled compound allowed us to demonstrate the concept of developing targeted α-particle therapeutics that undergo decay in the cell nucleus; however, AUdR is not suitable for patient treatment because of its lack of tumor specificity and poor in vivo stability.

A major challenge in the development of specific and effective cancer treatments is that exploiting a molecular target that is accessible (i.e., cell membrane or extracellular matrix) is critical for achieving tumor selectivity while delivery of the therapeutic agent to the cell nucleus is generally required for maximizing the therapeutic effect. An intriguing approach to this conundrum is to use a hybrid molecule to achieve both goals by linking together peptides with different functionalities. Originally, this was attempted through the use of bifunctional cross-linking reagents (9, 10). We have now used a recombinant technology to develop targeted therapeutic agents that include modules for addressed delivery both to tumor cells and into compartments within these cells that are the most sensitive to the drug (11, 12). These modular recombinant transporters (MRTs) are polypeptides possessing (1) an internalizable ligand module providing target cell recognition and subsequent receptor-mediated endocytocis by the cell; (2) an endosomolytic module ensuring escape of the MRT from the endosomes; (3) a module containing a nuclear localization sequence (NLS), thereby enabling interaction of the transporter with importins, the intracellular proteins ensuring active translocation into the cell nucleus; and (4) a carrier molecule for attachment of the drug (i.e., photosensitizer, radionuclide; Fig. 1). A significant advantage of MRTs is the interchangeable nature of the modules, offering the exciting prospect of generating an MRT cocktail using a mixture of ligands tailored to the molecular profile of an individual patient’s tumor.

Fig. 1.

Steps in targeting of modular recombinant transporter (MRT) from surface to nucleus of cancer cell. EGF = epidermal growth factor.

In the present study, we evaluated the potential utility of using an MRT for targeting 211At to cancer cells overexpressing epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (EGFR). The results of this study have demonstrated that an MRT with four functional modules retained high affinity and specific binding to EGFR after radiolabeling. An MRT labeled using N-succinimidyl 3-[211At]astato-5-guanidinomethylbenzoate (13) was significantly more cytotoxic than [211At]astatide against three different EGFR-expressing human cancer cell lines.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Cell lines

The human epidermoid carcinoma cell line A431 (14) (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and the human glioblastoma cell lines D247 MG (15) and U87MG.wtEGFR (16) (both provided by Dr. Darell Bigner, Duke University Medical Center) have been reported to overexpress EGFR. The cells were cultured in Zinc Option medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 U/mL) at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. All tissue culture reagents were obtained from Gibco/Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Modular recombinant transporter

The MRT used in these experiments was DTox-HMP-NLS-EGF of 76.3 kDa (heretofore designated as MRT), where DTox is the translocation domain of diphtheria toxin, serving as an endosomolytic module; HMP is an E. coli hemoglobin-like protein, serving as a carrier module; NLS is the optimized simian vacuolating virus 40 (SV40) large T-antigen NLS; and EGF is epidermal growth factor and served as the ligand module (12). The MRT was purified to >98% purity on Ni-NTA-agarose (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) according to the standard procedure furnished by the supplier. The MRT modules retained their functions. They demonstrated high-affinity interaction with EGFR and α/β-importin dimers, ensuring nuclear transport of NLS-containing proteins, and they formed holes in lipid bilayers at endosomal pH and accumulated in the nuclei of A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells (12).

Radionuclides

Sodium [125I]iodide and sodium [131I]iodide with a specific activity of 2,200 Ci/mmol and 1,200 Ci/mmol, respectively, were obtained from Perkin-Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). 211At was produced at the Duke University Medical Center by bombarding a natural bismuth internal target with 28-MeV α-particles by way of the 209Bi(α, 2n)211At reaction and isolated from the cyclotron target using a dry distillation method (17).

Labeling MRT with 125I and 211At using N-succinimidyl 3-[211At]astato-5-guanidinomethylbenzoate and its 125I analogue SGMIB

Detailed methods for the radiosynthesis of N-succinimidyl 3-[211At]astato-5-guanidinomethylbenzoate (SAGMB) and its 125I analogue SGMIB have been previously published (13, 18). In brief, sodium [125I]iodide was added to a solution of 3% (vol/vol) acetic acid (3 µL), 30% (wt/vol) tert-butylhydroperoxide (5 µL), and a solution of N-succinimidyl 4-[N1,N2-bis(tert-butyloxycarbonyl) guanidinomethyl]-3-(trimethylstannyl)benzoate (0.2 mg, 15 µL), all in chloroform. After stirring at room temperature for 30 min, [125I]SGMIB-Boc was isolated by normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Conversion to [125I]SGMIB was accomplished by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid for 5 min at room temperature. After evaporating the solvent under argon, any trace amounts of trifluoroacetic acid that remained were co-evaporated three times with 25 µL ethyl acetate. A similar procedure was used for the synthesis of SAGMB, except for starting with 20–74 MBq 211At in 1–3 µL 0.1N NaOH. A solution of the MRT (50 µL, 3 mg/mL) in 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.5) was added to either [125I]SGMIB or [211At]SAGMB, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min, after which 150 µL of 10 mM glycine was added to terminate the reaction. The radiolabeled polypeptide conjugates were purified by gel-filtration through a PD-10 column (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA) that was eluted with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5). The yield for these radioconjugation reactions was 70–80%, and >99% of the isolated conjugate was precipitable in trichloroacetic acid. The specific activity of the SAGMB-MRT preparations used in the cytotoxicity experiments ranged from 133 to 192 kBq/µg.

Radioiodination by Iodogen method

For radioligand assays and comparative experiments, human EGF (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) and the MRT were labeled directly with 125I and 131I, respectively, using Iodogen (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The proteins and 10–20 MBq of radioiodide in 0.05 M sodium borate buffer (pH 8.5) were incubated in glass vials coated with 10 µg of Iodogen for 15 min on ice. Radioiodinated EGF and MRT were purified as described in the previous section.

Binding assays

The EGFR status of the cells was tested using [125I]iodoEGF (specific activity 4.4 TBq/mmol). In brief, the cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates. After 36 h, serial dilutions of [125I]iodoEGF in 0.25 ml were added to the wells in triplicate, and the cells were incubated with ligands for 14 h at 4°C in the medium without sodium bicarbonate supplemented with 10 mg/mL of bovine serum albumin and 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7.5). The addition of nonlabeled EGF, 1 µM, was used to measure nonspecific binding. The cells were washed four times with the same medium on ice, lysed in 0.5 M NaOH for 30 min, and the radioactivity associated with the cell lysates was measured. The binding of [125I]iodoMRT was determined in a similar fashion. Competition experiments were carried out in triplicate with labeled [125I]iodoEGF under the same conditions as the binding assay. The data were analyzed using nonlinear-regression techniques with a least-squares curve fitting (19).

Evaluation of internalization and cellular retention of labeled MRT

Internalization and cellular retention assays (13, 18) were performed in paired-label format using A431 cells as the EGFR-expressing target. Two assays were performed, one comparing [125I]SGMIB-MRT to 131I-labeled MRT prepared using Iodogen and the other comparing [211At]SAGMB-MRT to 131I-labeled MRT labeled using Iodogen. In brief, approximately 5 × 105 cells per well in 24-well plates were incubated in 0.25 mL of medium containing 40 nM of each radiolabeled MRT (~37 kBq) for 1 h at 4°C. After washing, the plates were brought to 37°C and processed in triplicate at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h as follows. The surface-bound radioactivity was removed from the washed cells by trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid solution (20), with subsequent centrifugation on a desktop centrifuge, followed by additional washing of the cells with the medium. We used a trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid wash instead of acidic buffers because the MRT can interact with lipid membranes at an acidic pH (12). The counts in the cell culture medium, washes (cell surface-bound), and cell pellets (internalized) were determined using a dual-channel automated gamma counter and were expressed as the percentage of activity initially bound to the cells after the 1 h incubation at 4°C.

The kinetics of binding and accumulation of [125I]SGMIB-MRT was measured in triplicate at 15 and 30 min and 1, 2, 3, and 4 h. Approximately 7 × 105 A431 cells per well in 24-well plates were incubated in 0.25 mL of medium with 90 nM of the labeled MRT at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. Incubations with the addition of 1 µM nonlabeled EGF were done in parallel wells to assess for nonspecific binding and accumulation.

Cytotoxicity assays

The cells from each line were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 per well in 6-well plates. At 36–48 h later, the plates were washed, and 12 dilutions of either [211At]SAGMB-MRT (0–100 kBq/mL) or [211At]astatide (0–700 kBq/mL) were added in triplicate to the cells in a total volume of 550 µL of medium. The cells were incubated with the 211At-labeled MRT or [211At]astatide for the indicated time at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. After the incubation, the cells were trypsinized, resuspended, counted, and seeded for a colony-forming assay in 25-cm2 flasks and grown at 37°C in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere. After 8–10 days, the colonies were stained and counted.

The results on the plots represent the mean values, with bars indicating the ± standard error of the triplicate wells.

RESULTS

Binding

Preliminary experiments were performed with [125I]iodoEGF to confirm the presence of EGFR on these cell lines. Scatchard analyses of the binding data indicated that the average number of EGFRs per cell were A431, 2.9 × 106, D247 MG, 2.4 × 105, and U87MG.wtEGFR, 4.3 × 106. The binding by EGFR of the MRT was assessed using A431 human epidermoid carcinoma and U87MG.wtEGFR human glioma cells overexpressing EGFR. The dissociation constant, Kd, for the MRT obtained from the displacement curves (competition of the unlabeled MRT with [125I]iodoEGF, Fig. 2) was 29.3 and 21 nM for the A431 and U87MG.wtEGFR cells, respectively. The dissociation constant determined by Scatchard analysis of the binding of [125I]SGMIB-MRT to A431 cells yielded a Kd of 22 nM, consistent with minimal alteration in MRT affinity for EGFR as a consequence of radiolabeling.

Fig. 2.

Radioligand binding analysis of [125I]iodoEGF and modular recombinant transporter (MRT) binding to (A) A431 carcinoma and (B) U87MG.wtEGFR glioma cells. Indicated concentrations of the MRT and either 2.2 nM [125I]iodoEGF (A) or 1.4 nM [125I]iodoEGF (B) were added to the cells and incubated at 4°C for 14 h.

The kinetics of binding and receptor-mediated internalization of [125I]SGMIB-MRT by the A431 cells were investigated during a 4-h period in both the presence and the absence of 1 µM EGF to determine the contribution of nonspecific processes. As shown in Fig. 3A, the total cell-associated activity (membrane bound plus intracellular) increased with time. Likewise, the fraction of cell-associated activity present in the intracellular compartment also increased with time. After a 4-h incubation period, the average number of MRT molecules per cell present on the cell surface and in the intracellular compartment was calculated as 2.5 × 105 and 9.5 × 105, respectively. The contribution of nonspecific membrane-bound and internalized molecules to total cell-associated activity was <4% and ≤0.5%, respectively (Fig. 3B). From these results, and taking into account the 7.2-h half life of 211At, a 4-h incubation period was used for most of the cytotoxicity assays.

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of binding and accumulation of [125I]SGMIB modular recombinant transporter (MRT) by A431 cells. (A) Total cell-associated MRT molecules (black squares); total (black rhombi) and specific (white rhombi) membrane-bound molecules; total (black triangles) and specific (white triangles) internalized molecules, all expressed in molecules of MRT per cell. (B) Nonspecific membrane (white squares) and internalized (black downward triangles) MRT, expressed as percentage of total cell-associated activity at indicated time.

Internalization and cellular retention of labeled MRT

Two paired-label assays were performed with the EGFR-expressing A431 cell line to determine the effect of the labeling method on the cellular retention of radioactivity. At every point studied, the percentage of radioiodine activity initially bound to the cells for [125I]SGMIB-MRT (Fig. 4) and [211At]SAGMB-MRT (Fig. 5) that was present in the intracellular compartment was significantly greater (p < 0.05; paired Student’s t test) than that for MRT labeled with 131I using Iodogen, with the difference increasing with time. Complementary differences were observed in the cell culture supernatant, for which the percentage of initially bound activity was significantly greater (p < 0.05) in both studies for MRT labeled using Iodogen. Intracellular activity peaked at either 1 h (Iodogen) or 2 h (SGMIB, SAGMB) but declined much more slowly for MRT labeled using the guanidine-substituted conjugation agents. After a 4-h incubation period at 37°C, the intracellular counts accounted for 56.4% ± 3.6% of the initially bound activity with SGMIB labeling compared with 15.5% ± 0.8% with Iodogen (Fig. 4). Likewise, the use of SAGMB for MRT labeling resulted in a more than threefold intracellular compartment delivery advantage compared with Iodogen labeling (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Paired-label internalization of radioiodinated modular recombinant transporter (MRT) by A431 cells. (A) [125I]SGMIB-MRT; (B) 131I Iodogen-labeled MRT. Data expressed as percentage of total activity initially bound to cells in incubation medium (rhombi), internalized (circles), and cell surface (squares).

Fig. 5.

Paired-label internalization of 211At- or 131I-labeled modular recombinant transporter (MRT) by A431 cells. (A) [211At]SAGMB-MRT; (B) 131I Iodogen-labeled MRT. Data expressed as percentage of total activity initially bound to cells in incubation medium (rhombi), internalized (circles), and cell surface (squares).

Cytotoxicity

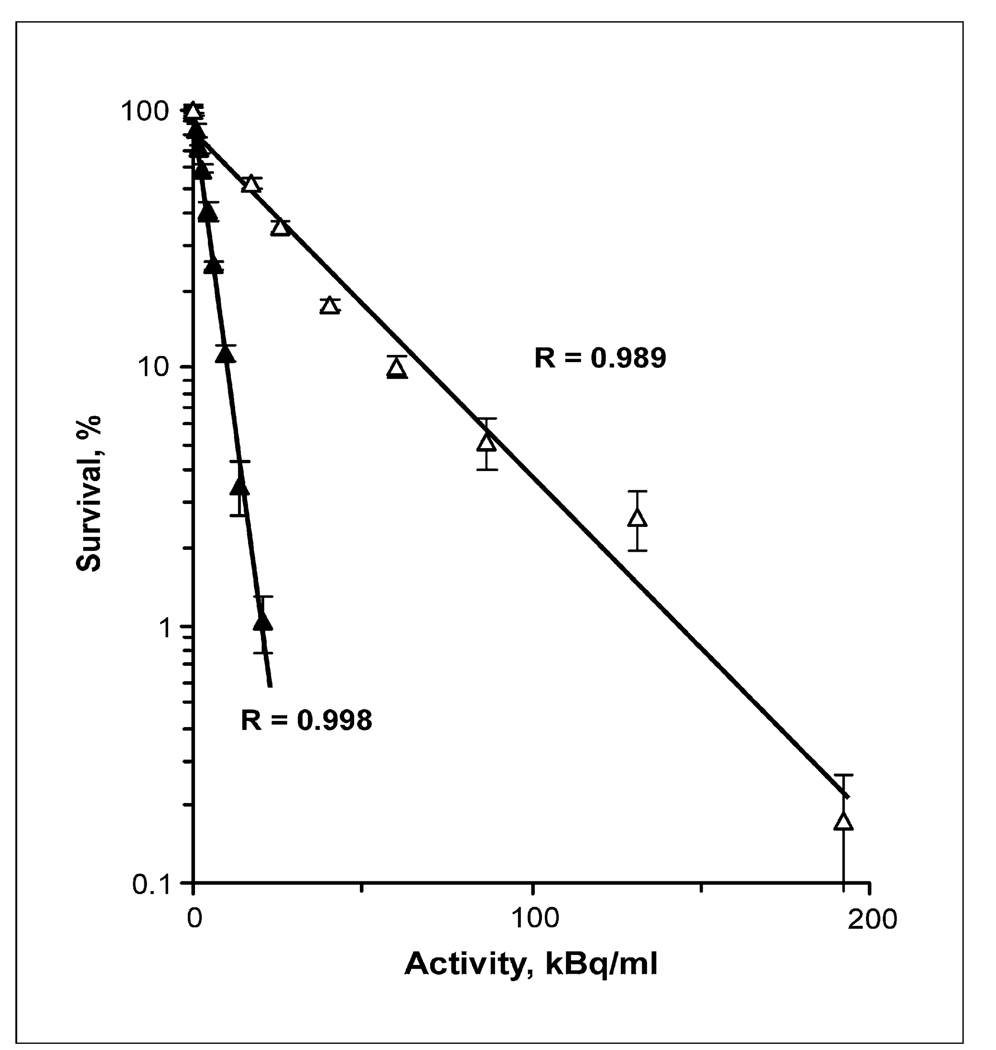

The clonogenic survival of A431, U87MG.wtEGFR, and D247 MG cells after a 4-h incubation period with varying activity concentrations of [211At]SAGMB-MRT and as a control for nonspecific killing, [211At]astatide, is presented in Fig. 6. The activity concentrations required to reduce survival to 37% (A37) were determined by regression analysis. The A37 values for [211At]SAGMB-MRT were significantly lower than those for [211At]astatide for all three cell lines. With A431 carcinoma cells (Fig. 6A), U87MG.wtEGFR (Fig. 6B) glioma cells, and D247 MG (Fig. 6C) glioma cells, the A37 values for astatide and SAGMB-MRT were 285 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 257–314) and 19.7 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 24.4–15.9; ratio, 14.5), 98.5 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 85.6–113.5) and 11.9 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 10.6–13.4; ratio, 8.25), and 69 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 62.5–76.5) and 3.8 kBq/mL (95% confidence interval, 3.3–4.4; ratio, 18.3), respectively. An additional cytotoxicity assay was performed with A431 cells incubated for 21 h 40 min with both 211At-labeled molecules. This period was equivalent to three physical half lives of 211At, with the result that the vast majority of the 211At decay occurred during the incubation period. The A37 value for [211At]astatide and [211At]-SAGMB-MRT was 32.6 kBq/mL and 4.4 kBq/mL (ratio, 7.4), respectively (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Clonogenic survival of (A) A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells and (B) U87MG.wtEGFR and (C) D247 MG human glioma cells after exposure for 4 h to varying activity concentrations of [211At]SAGMB-MRT (closed symbols) and [211At]astatide (open symbols).

Fig. 7.

Clonogenic survival of A431 human epidermoid carcinoma cells after exposure for 21 h 40 min to varying activity concentrations of [211At]SAGMB-MRT (closed symbols) and [211At]astatide (open symbols).

DISCUSSION

We have recently described a novel MRT, DTox-HMP-NLS-EGF, for targeting drugs to the nucleus of cancer cells overexpressing EGFR (12). The MRT was evaluated in the present study as a potential carrier for targeted radionuclide therapy for the numerous cancers that overexpress EGFR (21).

Our previous investigations (11, 12) with different MRTs carrying photosensitizers clearly demonstrated that the drugs displayed cytotoxicity when added to target cells. In contrast, nontarget cells, which express few specific receptors or do not express them at all, remained alive. Specifically, EGFR-overexpressing A431 cells, which are target cells for the same MRT used in the present study, died within the drug-MRT concentration range that did not influence survival of the “normal” cells expressing few EGFR, NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (12). As shown in the present report, MRTs bind to, and internalize into, the target cells very selectively, in that 96% of binding and 99.5% of internalization were blocked when cell-surface EGFR was blocked by cold EGF. Thus, in the case of nontarget cells lacking EGFRs, the vast majority of [211At]astatinated MRT added to nontarget cells should remain noninternalized and unbound in the medium, such as is the case with free astatide ion, which was thus used as a control for nonspecific cytotoxicity.

These studies showed effective killing of glioma cell lines expressing an order of magnitude difference in average receptor number. Although the receptor number is an important parameter, it is important to remember that a significant reduction in cell survival with 211At-labeled targeted radiotherapeutic agents has been achieved with only an average of 1–10 decays/cell, a range that is several orders of magnitude less than the average EGFR number observed on most human tumor cell lines. Furthermore, the well-documented bystander effect of α-particle emitters (22) could help compensate for lower uptake of the 211At-labeled MRT in subpopulations in which the level of EGFR expression was relatively low.

Most receptors that are upregulated on cancer cells such as EGFR undergo rapid internalization after ligand binding. Because internalization can expose radioligands to additional catabolic processes, it is important that the radionuclide be retained intracellularly after the ligand has degraded. Our experience with the rapidly internalizing anti-EGFR variant III monoclonal antibody L8A4 has shown that labeling methods that result in the generation of charged catabolites after proteolytic degradation of the monoclonal antibody significantly increase tumor retention of the radiolabel. One of our optimal reagents, SAGMB, and its 125I analogue, SGMIB, have been shown to offer considerably greater tumor cell retention compared with conventional labeling approaches such as Iodogen (13, 18). The data presented here (Fig. 3) have confirmed this conclusion.

A combination of these approaches—the modular transporter for cell-specific nuclear delivery of antitumor drugs and the labeling method for permitting increased tumor retention of a radiolabel—has enabled the achievement of efficient killing of tumor cells overexpressing EGFR. In all cases, the survival curves were characterized by a lack of a shoulder at low activity concentrations, such as would be expected for high-LET radiation (1). With an exposure equivalent to three half lives of 211At, >87% of the decay occurred during the incubation period. The A37 value for [211At]astatide and [211At]SAGMB-MRT was 32.6 kBq/mL and 4.4 kBq/mL, respectively (7.4-fold difference; Fig. 7). We hypothesize that the enhanced cytotoxicity of [211At]SAGMB-MRT compared with [211At]astatide reflects a geometrically more favorable site of decay relative to the radiosensitive cell nucleus and the effects of α-particle recoil nuclei, which presumably require localization in close proximity to the cell nucleus to be cytotoxic owing to their <0.1-µm range.

In the previous study (7, 8) comparing the cytotoxicity of DNA-incorporated AUdR and [211At]astatide, the A37 needed for the labeled thymidine analogue was about 1.9 times lower than the A37 ratio of 7.4 observed for SAGMB-MRT: astatide. The enhanced cytotoxicity of SAGMB-MRT compared with AUdR might be attributable to receptor-specific targeting of the former vs. the S-phase limited uptake of the latter, more stable labeling chemistry, and/or differences in the kinetics of cell binding and intracellular routing.

The A37 values observed with a 4-h incubation period differed considerably among the three cell lines for both [211At]-SAGMB-MRT and [211At]astatide. That it occurred with both labeled molecules suggests that this behavior might reflect differences in the sensitivity of the cell lines to high-LET radiation. An inverse relationship between the EGFR number and radiocurability has been reported (23), and the results obtained in the present study showed a similar trend. This was attributed to a lack of sensitivity to apoptosis in tumors with high EGFR, which might differ for high- and low-LET radiation.

In the present study, clonogenic survival was expressed as a function of the initial activity concentration of the labeled molecule present in the incubation medium. In particular, with [211At]SAGMB-MRT, effective killing of three different human cancer cell lines, with an A37 of <25 kBq/mL in all cases, was achieved. The present results can be compared with those obtained previously after exposure of D247 MG human glioma cells to other 211At-labeled compounds. The A37 value observed for [211At]SAGMB-MRT was lower than that observed for [211At]AUdR (7, 8) and several 211At-labeled monoclonal antibodies (24), including 211At-labeled chimeric 81C6, which has shown promise as a targeted radiotherapeutic agent in recurrent glioma patients (25). With regard to eventual clinical use of 211At-labeled MRT, we believe that settings such as surgically created glioma resection cavities, in which the labeled drug can be applied locally, would be best to avoid interaction with normal peripheral tissues expressing large amounts of EGFRs (e.g., liver) and to take advantage of the almost complete absence of EGFRs in the normal brain cortex (26).

CONCLUSION

In the present study, we have demonstrated the proof of principle for using MRTs as a platform for developing targeted radiotherapeutic agents for cancer therapy. With [211At]SAGMB-MRT, effective killing of three human cancer cell lines overexpressing EGFR was observed. This strategy can be readily expanded to deliver radionuclides to other molecular targets by changing the nature of the ligand module. For these reasons, MRTs warrant additional evaluation as a targeted radiotherapy approach that ultimately could be tailored to the tumor molecular signature of an individual patient.

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical assistance of Donna Affleck and Phil Welsh is gratefully acknowledged.

Supported in part by the U.S. Civilian Research and Development Foundation Grant RUB-02-2663-MO-05, Dutch-Russian (NWORFFI) Scientific Cooperation Grant 047.017.025, Russian Foundation for Basic Research Grant 06-04-49273, and U.S. National Institutes of Health Grants CA42324 and NS20023.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hall EJ. Radiobiology for the radiologist. 4th ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akabani G, Carlin S, Welsh P, et al. In vitro cytotoxicity of 211At-labeled trastuzumab in human breast cancer cell lines: Effect of specific activity and HER2 receptor heterogeneity on survival fraction. Nucl Med Biol. 2006;33:333–347. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daghighian F, Barendswaard E, Welt S, et al. Enhancement of radiation dose to the nucleus by vesicular internalization of iodine-125–labeled A33 monoclonal antibody. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1052–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zidenberg-Cherr S, Parks NJ, Keen CL. Tissue and subcellular distribution of bismuth radiotracer in the rat: Considerations of cytotoxicity and microdosimetry for bismuth radiopharmaceuticals. Radiat Res. 1987;111:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roessler K, Eich G. Nuclear recoils from 211At decay. Radiochimica Acta. 1989;47:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goddu SM, Howell RW, Bouchet LG, et al. MIRD cellular S values: Self-absorbed dose per unit cumulated activity for selected radionuclides and monoenergetic electron and alpha particle emitters incorporated into different cell compartments. Reston, VA: Society of Nuclear Medicine; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaidyanathan G, Larsen RH, Zalutsky MR. 5-[211At]astato-2′-deoxyuridine, an α-particle emitting endoradiotherapeutic agent undergoing DNA incorporation. Cancer Res. 1996;56:204–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen RH, Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. The cytotoxicity of α-particle emitting 5-[211At]astato-2′-deoxyuridine in human cancer cells. Int J Radiation Biol. 1997;72:79–90. doi: 10.1080/095530097143563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhlynina TV, Rosenkranz AA, Jans DA, et al. Insulin-mediated intracellular targeting enhances the photodynamic activity of chlorin e6. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1014–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhlynina TV, Jans DA, Rosenkranz AA, et al. Nuclear targeting of chlorin e6 enhances its photosensitizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20328–20331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenkranz AA, Lunin VG, Gulak PV, et al. Recombinant modular transporters for cell-specific nuclear delivery of locally-acting drugs enhance photosensitizer activity. FASEB J. 2003;17:1121–1123. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0888fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilyazova DG, Rosenkranz AA, Gulak PV, et al. Targeting cancer cells by novel engineered modular transporters. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10534–10540. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Bigner DD, et al. N-succinimidyl 3-[211At]astato-4-guanidinomethylbenzoate: An acylation agent for labeling internalizing antibodies with α-particle emitting 211At. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:351–359. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velikyan I, Sundberg AL, Lindhe O, et al. Preparation and evaluation of 68Ga-DOTA-hEGF for visualization of EGFR expression in malignant tumors. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1881–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner MH, Humphrey PA, Bigner DD, et al. Growth effects of epidermal growth factor (EGF) and a monoclonal antibody against the EGF receptor on four human glioma cell lines. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;77:196–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00687431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luwor RB, Johns TG, Murone C, et al. Monoclonal antibody 806 inhibits the growth of tumor xenografts expressing either the de2-7 or amplified epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) but not wild-type EGFR. Cancer Res. 2001;55:5355–5361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zalutsky MR, Zhao X-G, Alston KL, et al. High-level production of α-particle emitting 211At and preparation of 211At-labeled antibodies for clinical use. J Nucl Med. 2001;42:1508–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Li J, et al. A polar substituent-containing acylation agent for the radioiodination of internalizing monoclonal antibodies: N-succinimidyl 4-guanidinomethyl-3-[131I]iodobenzoate ([131I]SGMIB) Bioconjugate Chem. 2001;12:428–438. doi: 10.1021/bc0001490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zakharova OM, Rosenkranz AA, Sobolev AS. Modification of fluid lipid and mobile protein fractions of reticulocyte plasma membranes affects agonist-stimulated adenylate cyclase: Application of the percolation theory. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1236:177–184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(95)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams JA, Bailey AC, Roach E. Temperature dependence of high-affinity CCK receptor binding and CCK internalization in rat pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1988;254:G513–G521. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.4.G513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocha-Lima CM, Soares HP, Raez LE, et al. EGFR targeting of solid tumors. Cancer Control. 2007;14:295–304. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mothersill C, Seymour CB. Radiation-induced bystander effects—Implications for cancer. Nature Revs Cancer. 2004;4:158–164. doi: 10.1038/nrc1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akimoto T, Hunter NR, Buchmiller L, et al. Inverse relationship between epidermal growth factor receptor expression and radio-curability of murine carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2884–2890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen RH, Akabani G, Welsh P, et al. The cytotoxicity and microdosimetry of astatine-211-labeled chimeric monoclonal antibodies in human glioma and melanoma cells. in vitro. Radiat Res. 1998;149:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zalutsky MR, Reardon DA, Akabani G, et al. First clinical experience with α-emitting astatine-211: Treatment of recurrent brain tumor patients with 211At-labeled chimeric 81C6 anti-tenascin monoclonal antibody. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:30–38. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Yong WH, Sun Y, et al. Receptor-targeted quantum dots: Fluorescent probes for brain tumor diagnosis. J Biomed Optics. 2007;12:044021. doi: 10.1117/1.2764463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]