Abstract

Research has demonstrated the efficacy of brief motivational interventions (BMI) and alcohol expectancy challenge (AEC) in reducing alcohol use and/or problems among college students. However, little is known about variables that may qualify the effectiveness of these approaches. The present analyses tested the hypothesis that need for cognition (NFC), impulsivity/sensation-seeking (IMPSS) and readiness to change (RTC) would moderate the effects of BMI and AEC. Participants (N = 335) were heavy drinking college students enrolled in a randomized 2×2 factorial study of BMI and AEC. Latent growth curve analyses indicated significant interactions for BMI × NFC and AEC × RTC on alcohol use but not problems. Simple slopes analyses were used to probe these relationships and revealed that higher levels of NFC at baseline were associated with a stronger BMI effect on drinking outcomes over time. Similarly, higher levels of baseline RTC were associated with stronger AEC effects on alcohol use. Future preventive interventions with this population may profit by considering individual differences and targeting approaches accordingly.

Keywords: college students, alcohol use, individual differences, brief interventions

Considerable research has documented the efficacy of brief motivational interventions (BMI) in reducing alcohol use and related negative consequences among college students (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Larimer & Cronce, 2002, 2007). Additionally, modest support has been demonstrated for the efficacy of alcohol expectancy challenge (AEC; Darkes & Goldman, 1993, 1998; Wood, Capone, Laforge, Erickson, & Brand, 2007), particularly among men. However, little is known about individual-level variables that may influence the effectiveness of these approaches (e.g., C. Dunn, Deroo, & Rivara, 2001). Identification of moderators of alcohol focused interventions may aid efforts to target interventions appropriately, potentially boosting effectiveness.

Research examining moderators of BMI effectiveness is limited. Fromme and Corbin (2004) found that greater readiness to change drinking was associated with lower levels of alcohol use following a group intervention. A recent report also found support for readiness to change in predicting drinking outcomes, although it did not demonstrate a moderating effect. However, in the same study self-regulation did moderate BMI effects in that students who endorsed greater self-regulation skills benefitted more from the BMI (Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2007).

Similarly, research investigating moderators of AEC effects is also limited. To date, gender appears to be the most relevant moderating variable, albeit inconsistently, with some studies showing limited efficacy in women (Weirs & Kummeling, 2004) and others showing no effectiveness (M. E. Dunn, Lau, & Cruz, 2000; Musher-Eizenman & Kulick, 2003; Weirs, Van de Luitgaarden, Van den Wildenberg, & Smulders, 2005). Our own previous research revealed gender equivalence across both BMI and AEC conditions, suggesting uniform effects on drinking outcomes (Wood et al., 2007). These outcomes were recently replicated for AEC (Lau-Barraco & Dunn, 2008). Further research is needed to elucidate additional moderators of intervention effects in order to refine existing approaches and inform the development of new ones.

In considering potential moderators of intervention effects for the present study, we sought to broaden the scope of individual difference variables than has previously been studied. We were guided in our efforts by previous social psychological research and etiological studies of alcohol use. One promising construct is need for cognition (NFC), which refers to the tendency to engage in and enjoy effortful cognitive processing (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). From this perspective, individuals high in NFC make sense of their world through reflection and inquiry and show an affinity for tasks that require reasoning and problem-solving. NFC has been shown to be a consistent moderator of attitude-behavior relations (Cacioppo, Petty, Feinstein, & Jarvis, 1996).

Another potential moderator of intervention effectiveness is readiness to change (RTC), a key concept in theories of behavior change, particularly those based on the principles of motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The transtheoretical model (TTM; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992) proposes that readiness to change a given behavior progresses through a series of five stages: precontemplation, in which an individual is not considering change; contemplation, in which an individual experiences ambivalence and begins to consider the risks/rewards of change; preparation, where the benefits of change outweigh the costs and planning for change occurs; action, in which steps are taken to implement the plan for change; and maintenance, which focuses on perpetuating the behavior change. These stages are not viewed as a linear progression, but rather as a cycle through which an individual may move back and forth over time (DiClemente, Schlundt, & Gemmell, 2004). Among college students, higher levels of readiness have been observed in heavier drinkers who experience greater negative consequences (Shealy, Murphy, Borsari, & Correia, 2007). Additionally, greater readiness to change has been associated with reductions in alcohol use and problems in this population (Carey, Henson et al., 2007).

Finally, a growing body of literature has implicated behavioral undercontrol, an index of personality traits including impulsivity and sensation-seeking (IMPSS), in the etiology of alcohol involvement among college students (e.g., Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991). Greater levels of behavioral undercontrol have consistently been associated with greater alcohol use and problems, particularly in the context of a positive family history of alcoholism (Capone & Wood, 2008; Finn, Sharkansky, Brandt, & Turcotte, 2000; Grekin & Sher, 2006). Likewise, behavioral undercontrol traits have been shown to affect treatment outcomes among adult cocaine (Patkar et al., 2004) and alcohol (Muller, Weijers, Boning, & Wiesbeck, 2008) dependent individuals, as well as substance use treatment seeking adolescents (Winters, Stinchfield, Latimer, & Stone, 2008). Thus, these personality traits may reflect underlying temperaments that may make certain individuals less responsive to intervention efforts but to our knowledge have not been examined as moderators of alcohol interventions in college populations.

The Present Study

The aim of the present analyses was to add to the small body of research examining moderators of alcohol intervention effects among college students. Specifically, we investigated the moderating effects of need for cognition (NFC), readiness to change (RTC) and impulsivity/sensation-seeking (IMPSS) on the relationships between BMI and AEC and drinking outcomes. Due to the reflective nature of the individualized-feedback BMI approach, we hypothesized that NFC would moderate its effects such that individuals higher in NFC would benefit more from the intervention than those lower on this trait. Based on the literature described above, we also hypothesized that RTC and IMPSS would moderate the effects of both BMI and AEC on alcohol use and related problems such that individuals high on RTC and low on IMPSS would be more responsive to these interventions.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 335 heavy drinking college students enrolled in a 2 × 2 factorial study of BMI and AEC. Heavy drinking status was defined as consumption of 14 or more drinks per week for men (10 or more for women), at least one episode of heavy drinking during the past month, and endorsement of two or more alcohol-related consequences during the past year. Over half of the participants were women (52.5%) and the majority was White (89.5%). At baseline, men averaged 23.13 (SD = 10.69) drinks per week; women reported an average of 15.75 (SD = 7.27) drinks per week. Men reported an average of 9.92 (SD = 4.52) heavy drinking episodes in the 30 days prior to baseline, while women reported 9.53 (SD = 4.55) heavy drinking episodes.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions: BMI, AEC, a combined condition (BMI + AEC, counterbalanced), or assessment only (AO) control. Follow-up assessments were conducted one, three, and six months post-intervention. Attrition at each follow-up was 17.6%, 24.5%, and 27.5%, respectively. No differences were observed between completers and non-completers on the outcome variables; however, attrition was significantly higher among older participants and those in the AEC conditions. Of note, the majority of missing data in this study was due to dropout by design, rather than from exposure to the interventions. Specifically, we elected not to follow up those participants randomized to the AEC conditions (n = 45) who did not attend at least one of the two group AEC sessions. Accordingly, 76% of those missing at Time 2 (and 49% of those missing over all time points) were dropped from the study by design.

Details regarding recruitment of participants and intervention procedures have been reported elsewhere (Wood et al., 2007). Briefly, participants in the BMI conditions attended a one-on-one session (45-60 minutes) conducted by clinical psychology graduate students in which a personalized feedback report was reviewed. Discussion focused on the effects of alcohol at different blood alcohol levels (BAL), provision of normative information regarding alcohol use among college students, feedback on alcohol-related consequences, and strategies to reduce the risk of harm related to drinking.

Participants assigned to the alcohol expectancy challenge (AEC) conditions attended two group sessions (approximately 90 minutes each) in a simulated bar environment. Both sessions followed the same format—a placebo manipulation followed by an interactive discussion of alcohol expectancies. Participants who were 21 or older were randomly assigned to receive two beverages containing alcohol or placebo-alcohol (those who were under 21 received the nonalcoholic beverages). After engaging in a social activity, participants were asked to identify who in the group had consumed alcohol and who did not, including themselves. Guided discussions followed, highlighting misattributions about alcohol use (present in every session) and focusing on the positive and negative effects of alcohol in social situations (Session 1) and sexual contexts (Session 2).

Measures

In the context of a larger assessment battery, participants completed the following measures.

Outcome measures

Past 30 day alcohol use was assessed at each timepoint with the Timeline Followback (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1995), which utilizes a calendar format to aid recall. Two primary outcome variables were derived from the TLFB, total alcohol use (quantity/frequency) and heavy episodic drinking (five drinks on one occasion, four for women). Alcohol-related problems were assessed at each timepoint with the 36-item Young Adult Alcohol Problems Screening Test (YAAPST; Hurlbut & Sher, 1992). Response options reflected past month consequences and ranged from 0 (never) to 5 (4 or more times in the past month). Coefficient alphas at baseline and follow-ups ranged from.79 to.85.

Putative moderators

Need for Cognition (NFC) was assessed at baseline with the 18-item Need for Cognition Scale (Cacioppo, Petty, & Kao, 1984). Participants were asked to determine the degree to which each item characterized them (e.g., “I really enjoy a task that involves coming up with new solutions to problems”). Response options ranged from 0 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 4 (extremely characteristic) and were summed to a total score. The NCS has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Cacioppo et al., 1996); coefficient alpha was.87 in our sample. Impulsivity and willingness to take risks was assessed at baseline with the Impulsive Sensation Seeking (ImpSS) scale from Zuckerman and Kuhlman's Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ; Zuckerman, Kuhlman, Joireman, Teta, & Kraft, 1993). Response options for the 18 items (e.g., “I often do things on impulse”) were dichotomous (true/false) and summed to a total score. Coefficient alpha was.76. Finally, Readiness to Change drinking (RTC) was assessed with the single-item Contemplation Ladder, adapted from previous smoking research (Biener & Abrams, 1991). Participants chose among five response options, depicted graphically as a ladder, corresponding to level of motivational readiness (e.g., “I am thinking about changing my drinking”).

Analysis Plan

Details and results of the main outcome analyses were presented in Wood et al. (2007). The goal of the analyses reported here was to examine hypothesized moderators of intervention effects on drinking outcomes over the six months of follow-up. Accordingly, latent growth curve (LGC) analyses were conducted to examine the moderating effects of baseline measures of need for cognition (NFC), impulsivity/sensation-seeking (IMPSS), and readiness to change (RTC). Outcome variables were total alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking, and alcohol-related consequences. Moderator effects were examined separately for each of the three outcome variables in parallel LGC models. Each model examined main effects of the intervention conditions (BMI, AEC, BMI+AEC) and the moderator variable as well as intervention by moderator interaction terms. Continuous predictor variables were centered prior to creating interaction terms. All analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in Mplus Version 5 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2007).

Results

A total of 335 heavy drinking college students were randomized to the four experimental conditions. Preliminary analyses confirmed successful randomization as evidenced by the fact that groups did not differ on any of the background, moderator or outcome variables assessed at baseline. Due to elevated skewness on the alcohol problems variable, the log transform of this variable was used in the analyses presented here.

As previously reported (Wood et al., 2007), results of the LGC analyses revealed main effects of both intervention conditions such that BMI and AEC were associated with reductions in total alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking over time. BMI but not AEC was also associated with reductions in alcohol problems. Main effects were observed for RTC on total alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking and alcohol problems. In all cases, higher readiness was associated with lower levels of drinking/consequences over time. NFC and IMPSS did not exhibit main effects on any of the outcome variables.

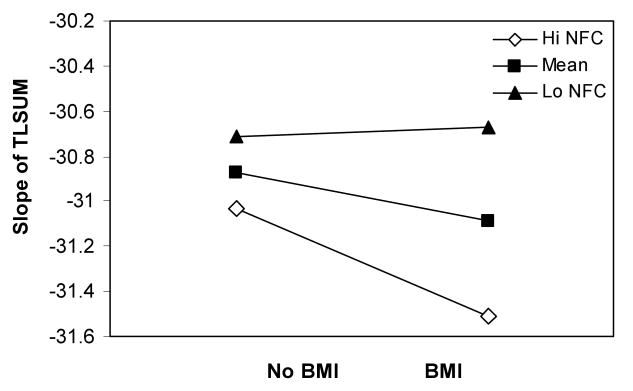

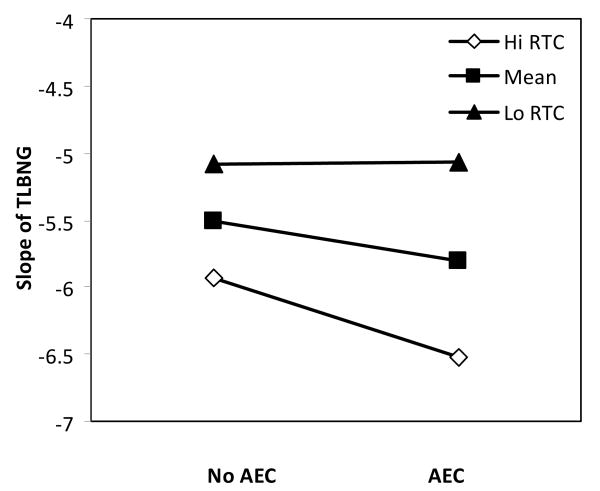

Two significant interactions were observed for both total alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking, BMI × NFC and AEC × RTC, and were associated with lower levels of drinking over time (see Figures 1 and 2). We did not observe significant moderator effects for any of the interactions involving the combined condition. Next, we conducted simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) in order to probe the significant interaction effects. For each moderator (NFC and RTC), separate variables were created that were ± 1 SD from the mean, resulting in “high” and “low” levels of the moderators. These variables were then included in separate LGC models along with an interaction term consisting of the revised moderator variable and the appropriate intervention condition (e.g., BMI × High-NFC, BMI × Low-NFC). As hypothesized, results of the simple slopes analyses indicated that higher levels of NFC were associated with stronger BMI effects on total alcohol use (β = -.48, p <.01) and heavy episodic drinking (β = -.52, p <.01) as compared to low NFC (ns). Also consistent with our hypotheses, higher levels of RTC were associated with stronger AEC effects on use (β = -.64, p <.01) and heavy drinking (β = -.59, p <.01) as compared to low RTC (ns).

Figure 1.

Moderation by NFC on total alcohol use (TLSUM).

Figure 2.

Moderation by RTC on heavy episodic drinking (TLBNG).

Discussion

We previously reported primary outcomes of this randomized factorial study of BMI and AEC in reducing college student drinking (Wood et al., 2007). In the present analyses we extend our findings and add to a small body of literature by examining the potential moderating effects of three individual difference variables—need for cognition, readiness to change, and impulsivity/sensation-seeking. Consistent with our hypotheses, two of the moderators (NFC and RTC) qualified intervention effects on drinking outcomes over time. Specifically, heavy drinking students demonstrating higher traits toward deliberative reflection benefitted more from BMI, as evidenced by greater reductions in both total alcohol use and heavy episodic drinking. A similar pattern emerged for RTC and the AEC condition; higher levels of motivational readiness at baseline were associated with stronger AEC effects on drinking over time. Contrary to our expectations, we did not observe a moderating effect of IMPSS in regard to either intervention. Additionally, no moderator effects involving the combined condition (BMI+AEC) were observed, likely due to the lack of power to detect higher order (3-way) interactions (Couper, Hosking, Cisler, Gastfriend, & Kivlahan, 2005).

Our findings are consistent with and extend previous research demonstrating an association between readiness to change and reductions in drinking among college students. For example, in the study by Carey et al. (2007), greater readiness was related to lower levels of drinking irrespective of whether or not students received a BMI. Fromme and Corbin (2004) found that RTC moderated intervention effects on one of five outcomes (heavy drinking) among voluntary but not mandated students. The present study revealed a main effect of RTC on alcohol use in our heavy drinking sample, in addition to a moderating effect of RTC for the AEC condition. Contrary to our expectations, we did not observe a moderational role for any of the individual difference variables on alcohol-related problems. Given the BMI intervention main effects on problems we reported earlier (Wood et al., 2007), this finding is consistent with the results of Carey et al. and suggests that BMI effects on problems are robust across several individual difference variables.

Strengths of this research include the factorial experimental design, the inclusion of women (particularly with respect to the AEC condition), and the examination of a range of outcome measures and individual difference variables in the context of LGCM. In addition to the strengths noted, there are limitations to the present research that should be considered. Consistent with the population of the study institution, our sample was largely ethnically homogenous. Consequently, our findings may not generalize to more diverse college student samples. Our overall attrition rate of 27.5% by the six-month follow-up is an additional limitation. While completers and non-completers did not differ at baseline according to gender or outcome measures of interest, they did differ significantly on age and AEC condition (the latter due in large part to our design decision).

Regarding our decision to drop individuals in the AEC conditions that could not be scheduled for at least one of the two sessions, two factors suggest that it is not a major limitation of the study. First, we observed no differences by overall attrition status on baseline alcohol use and related problems. Similarly, we did not observe any differences on these measures when comparing those dropped for AEC non-compliance with other dropouts or the remaining sample as a whole. Nonetheless, in retrospect, it would have been preferable to retain all randomized participants in the study, thus allowing for intent-to-treat analyses or complier average causal effect (CACE) modeling (Dunn et al., 2003).

Our findings that individual difference variables moderated intervention effects have clear implications for future preventive intervention efforts. In our study, individuals with tendencies to engage in effortful cognitive processing benefitted more from BMI, an intervention approach guided by personalized feedback and discussion. On the other hand, individuals who endorsed a higher degree of readiness to change their drinking benefitted more from the AEC, perhaps because this approach is more attuned to the “action” stage of motivational readiness (Prochaska et al., 1992). In addition to the placebo manipulation typically employed in the AEC, we focused on debunking the notion that “more is better” using an interactive demonstration clearly showing that effects typically viewed as desirable (e.g., sociability, relaxation) occur at lower doses. Definitive resolution of this interpretation awaits translational research that systematically investigates AEC intervention content through approaches such as dismantling designs (Couper et al., 2005). In aggregate, our results provide further support for the use of BMI and AEC approaches with heavy drinking students. Here we identified two individual difference variables that should be considered in the design and implementation of future intervention efforts with this population.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grant R29AA012241-01 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Mark D. Wood.

Footnotes

Author Note: Christy Capone is now affiliated with Providence VA Medical Center, 830 Chalkstone Avenue, Providence, RI 02908 and Brown University, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Box G-S121-4, Providence, RI 02912.

Contributor Information

Christy Capone, Brown University, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Box G-S121-4, Providence RI 02912.

Mark D. Wood, University of Rhode Island, Department of Psychology, 10 Chafee Road, Suite 8, Kingston RI 02881

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, Abrams DB. The Contemplation Ladder: validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology. 1991;10:360–365. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Feinstein JA, Jarvis WBG. Dispositional differences in cognitive motivation: The life and times of individuals varying in need for cognition. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119:197–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, Kao CF. The efficient assessment of need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1984;48:306–307. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone C, Wood MD. Density of familial alcoholism and its effects on alcohol use and problems in college students. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:1451–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Which heavy drinking college students benefit from a brief motivational intervention? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:663–669. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: a meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper DJ, Hosking JD, Cisler RA, Gastfriend DR, Kivlahan DR. Factorial designs in clinical trials: options for combination treatment studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66 15:24–32. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:344–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: process and structure in the alcohol expectancy network. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:64–76. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Schlundt D, Gemmell L. Readiness and stages of change in addiction treatment. American Journal on Addictions. 2004;13:103–119. doi: 10.1080/10550490490435777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96:1725–1742. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961217253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G, Maracy M, Dowrick C, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Dalgard OS, Page H, et al. Estimating psychological treatment effects from randomised trials with both non-compliance and loss to follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:323–331. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Lau HC, Cruz IY. Changes in activation of alcohol expectancies in memory in relation to changes in alcohol use after participation in an expectancy challenge program. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2000;8:566–575. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.4.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Sharkansky EJ, Brandt KM, Turcotte N. The effects of familial risk, personality, and expectancies on alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:122–133. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin W. Prevention of heavy drinking and associated negative consequences among mandated and voluntary college students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:1038–1049. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grekin ER, Sher KJ. Alcohol dependence symptoms among college freshmen: prevalence, stability, and person-environment interactions. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:329–338. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbut SC, Sher KJ. Assessing alcohol problems in college students. Journal of American College Health. 1992;41:49–58. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1992.10392818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention and treatment: a review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002:148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention, and treatment revisited: individual-focused college drinking prevention strategies 1999-2006. Addict Behav. 2007;32:2439–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muller SE, Weijers HG, Boning J, Wiesbeck GA. Personality traits predict treatment outcome in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychobiology. 2008;57:159–164. doi: 10.1159/000147469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musher-Eizenman DR, Kulick AD. An alcohol expectancy-challenge prevention program for at-risk college women. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:163–166. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. Fifth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patkar AA, Murray HW, Mannelli P, Gottheil E, Weinstein SP, Vergare MJ. Pre-treatment measures of impulsivity, aggression and sensation seeking are associated with treatment outcome for African-American cocaine-dependent patients. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2004;23:109–122. doi: 10.1300/J069v23n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shealy AE, Murphy JG, Borsari B, Correia CJ. Predictors of motivation to change alcohol use among referred college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2358–2364. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol timeline followback user's manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weirs RW, Kummeling RHC. An experimental test of an alcohol expectancy challenge in mixed gender groups of young heavy drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weirs RW, Van de Luitgaarden J, Van den Wildenberg E, Smulders FTY. Challenging implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions in young heavy drinkers. Addiction. 2005;100:806–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Stinchfield RD, Latimer WW, Stone A. Internalizing and externalizing behaviors and their association with the treatment of adolescents with substance use disorder. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood MD, Capone C, Laforge R, Erickson DJ, Brand NH. Brief motivational intervention and alcohol expectancy challenge with heavy drinking college students: a randomized factorial study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2509–2528. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Kuhlman DM, Joireman J, Teta P, Kraft M. A comparison of three structural models for personality: The Big Three, the Big Five, and the Alternative Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:757–768. [Google Scholar]