Introduction

The expulsive component of cough is generated primarily by the coordinated activity of the anterolateral abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis, external oblique, and internal oblique). Input from the brainstem cough neural networks (for review see (Iscoe, 1998)) to the motoneuron pools for these primary expiratory muscles is disrupted following cervical and thoracic injuries involving the ventral and ventrolateral spinal cord (Davis and Plum,1972). In the cat, the motoneuron pools for these four muscles all terminate at L3, but they have varying rostral extents with the rectus abdominis extending most rostrally (T4); the external oblique to T6; the transverses abdominis to T9; and the internal oblique to T13 (Miller, 1987). Further, from T1-L3, expiratory axons originating in the brainstem arborize expansively throughout the contralateral side of the spinal cord, creating an extensive network spanning several spinal segments (Merrill, 1974).

In the present study lateral T9/10 hemisections were made in adult cats. These lesions transect the descending brainstem expiratory pathways on one side of the spinal cord, disrupting pre-motor drive to the caudal, ipsilateral expiratory motoneuron pools. Cough pressure generation and rectus abdominis muscle activity were characterized pre- and post-injury. Expiratory muscle recordings were made from the rectus abdominis because it contributes to the generation of cough expulsive forces in the cat (Tomori and Widdicombe, 1969), plays a significant role in increasing abdominal cavity pressure during cough (Bolser et al., 2000), and is easily accessed for repeated assessments. Based upon extensive ipsi- and contralateral arborizations of descending expiratory axons as well as expiratory associated thoracic interneurons with crossed axons spanning multiple segments (Kirkwood et al., 1988), we hypothesized that features of the cough reflex would recover following a T9/10 lateral hemisection. Our findings support this hypothesis and show that, despite considerable disruption of descending pre-motor drive from the brainstem to motoneuron pools of the primary expiratory muscles, the cough motor system shows substantial function by 4 weeks (earliest time point studied) following thoracic spinal cord injury (SCI).

Methods

Cough production was assessed pre- and post-spinal T9/10 left hemisection in six specific-pathogen-free adult, spayed female cats (6–8 lbs, Liberty Laboratories, NY). Hemisections and post-op care were performed as described previously (Tester and Howland, 2008). Surgeries were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. Buprenorphine (0.02mg/kg) was given TID for 48h, and bladders expressed manually for 1–5 days, post-SCI. Cat body weights were closely monitored post-injury and were maintained within 5% (+/−) of their pre-injury weights. Cats were housed on thick cushions in the AALAC accredited animal facility and trained on a variety of locomotor tasks (5x/week) for a parallel study. Animal procedures were in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Florida’s IACUC.

Cough was assessed in isoflurane anesthetized, spontaneously breathing cats pre-injury and at 4, 13 and 21 wks post-SCI. Atropine sulfate (0.1 mg/kg, SQ) was given to block salivation and tracheal secretions. End-tidal CO2 was monitored and isoflurane levels adjusted to maintain this parameter within 4–5%. Cats were placed in the supine position, and a sterile abdominal field prepared. Paired bipolar Teflon-coated stainless steel wire electrodes were placed 2–3 mm apart in the left and right rectus abdominis muscles approximately 2 cm caudal to the iliac crest and 1 cm lateral to midline. A ground electrode was placed in the left hamstring. An esophageal balloon catheter was placed at the midthoracic level and cough elicited by mechanical stimulation of the vocal folds and epiglottis using an oral approach and a small length of flexible plastic tubing (Bolser, 1991; Bolser et al., 1993). Isoflurane was administered via a nose cone. Once animals reached a surgical plane of anesthesia, determined by lack of reflex responses to whisker stimulation, paw web pinch or cutaneous stimulation of the eye, the nose cone was removed and cough was mechanically elicited. Once the cough bout ended, the nose cone was replaced and the sequence repeated with the goal of collecting approximately 20 coughs for each cat. Following cough stimulation, animals were recovered and monitored for the next few hours to verify that they resumed eating and drinking.

Esophageal pressure (Pes) and left and right rectus abdominis (LRA and RRA) electromyograms (EMGs) were recorded. Pes (cmH2O) was used as it has been shown to reflect abdominal pressure (Bolser et al., 2000). The esophageal balloon catheter was calibrated prior to each experiment and placed in the midthoracic esophagus. The pressure response of the balloon catheter system was linear over the pressure range of coughing (0–120 mm Hg). EMGs were amplified and digitally band-pass filtered (200–5000 Hz). The EMGs were rectified and moving averages (sliding window 50 ms) of these signals were generated off-line using a custom script employing Spike2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Inc.). Coughs were identified by behavioral observation of the animal and the presence of Pes amplitude larger than 5 cm H2O in response to the mechanical stimulus. Six parameters were calculated: Pes, percentage of LRA and RRA normalized cough amplitudes, esophageal rise times, and LRA and RRA rise times. To obtain RA EMG normalized amplitudes, each cough amplitude was expressed as a percentage of the maximal burst at a given time point for each side in each cat. These normalized percentages were averaged for each cat at each time point. Statistical analyses were run on these normalized (percent) values of EMG magnitude. Rise times were determined as the elapsed time between 10% and 90% of the total rise time of the moving average. Individual cough rise times for each cat were averaged at each time-point.

Using SPSS software 14.0 (Chicago, IL), separate repeated measures, within-subjects ANOVAs were conducted to determine if esophageal parameters (pressure and rise time) differed across time points. Mixed (time × side) two-factor ANOVAs were conducted to determine if there was an effect of time or side on rectus abdominis EMG rise times and normalized percent amplitudes. Post-hoc Fishers LSD tests were used to isolate any differences identified with ANOVAs. Spearman correlation coefficients were conducted to determine if any variation in lesion size was associated with any of the behavioral parameters assessed. An α level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. Data are shown as averages ± standard deviations.

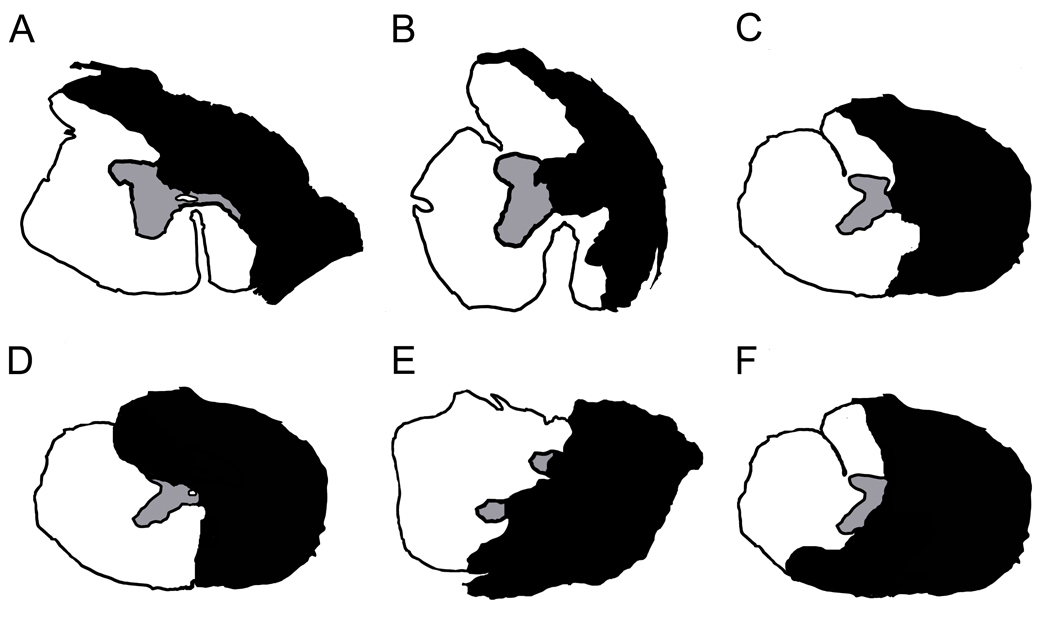

Following the last cough data collection at 21 wks post-SCI, cats were deeply anesthetized (sodium pentobarbital, >35 mg/kg I.P.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline (200–400 mls) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer (3.5L, pH 7.4). Spinal cord tissue was removed, blocked, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose-paraformaldehyde, and sectioned at 25um on a cryostat. Four of the cats’ lesions were cut coronally (axially) and the remaining two cut longitudinally. One section of every ten was mounted onto chrom alum and poly-L-lysine-coated slides (chromium potassium sulfate and poly-L-lysine, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO; gelatin, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) and processed with cresyl violet (cresyl violet with acetate, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis MO) and myelin (Eriochrome Cyanine R, Fluka, New York, NY) stains for basic histology to determine the extent of injury following procedures detailed previously (Tester and Howland, 2008). The damage for each animal at the lesion epicenter was determined by microscopic examination of cresyl violet and myelin stained sections throughout the lesion site and represented in cross section. For four of the cats, the lesion areas were directly outlined from cross sections of tissue (Fig. 1A, B, C, and E). For the remaining two cats, whose tissue had been cut longitudinally, the representations were produced by examining multiple longitudinal sections to appreciate the cross-sectional extent of the lesions which were then imposed upon a representative cross sectional drawing. (Fig. 1D, F).

Figure 1.

Cross-section lesion extents. The smallest lesions were incomplete hemisections with ipsilateral ventro-medial white matter sparing (A, B). The complete-hemisections had ipsilateral gray and white matter damage and contralateral gray and white matter sparing (C). The largest lesions were over-hemisections with variable contralateral gray and white matter damage dorsally and ventrally (D, E, F). White indicates areas of remaining tissue; Black indicates areas of tissue loss/damage and scar tissue.

Results

A total of 256 coughs from six cats were analyzed across four time points: pre-injury (n=37); 4 weeks post-hemisection (wphx, n=87); 13 wphx (n=75); and 21 wphx (n=57). Cresyl violet and myelin stained serial sections of each lesion were assessed to determine the extent of SCIs. The lesions ranged from under-hemisections with partial ipsilateral medial-ventral white matter sparing (Fig. 1A,B) to complete a hemisection (Fig. 1C) to over-hemisections with variable disruption of contralateral gray and white matter in the dorsal or ventral aspect of the spinal cords (Fig. 1D, E, F). Spearman correlation coefficients showed no significant relationship between lesion size and behavioral parameters suggesting that the expiratory pressures and bilateral RA EMGs features assessed in this study were not influenced by these injury differences.

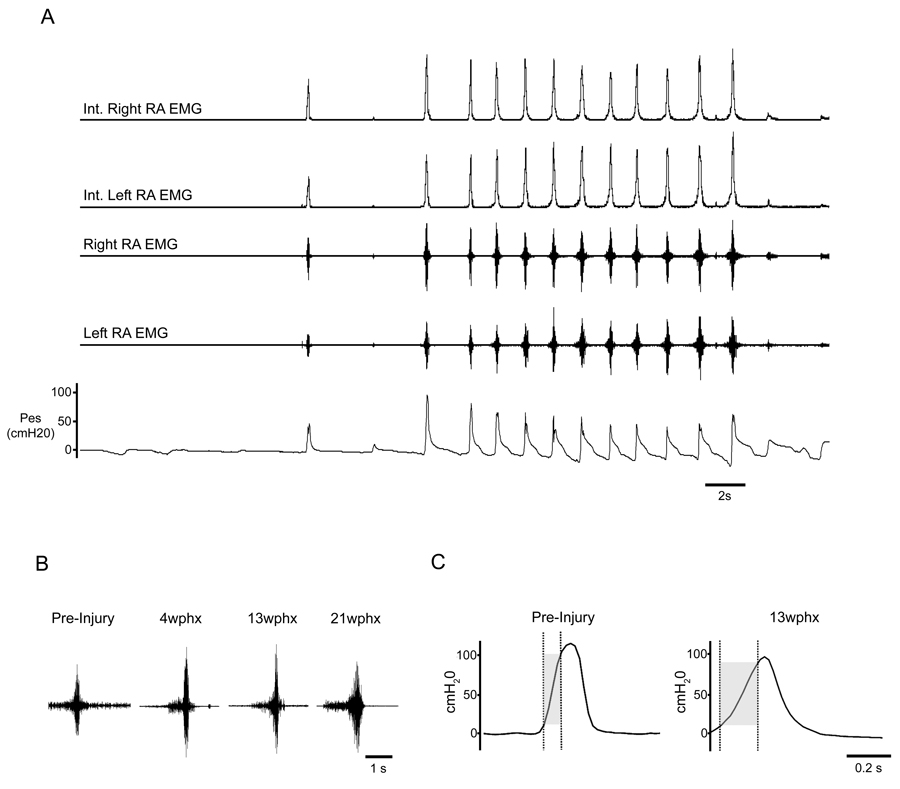

All cats generated coughs pre- and post-injury under anesthesia in response to mechanical stimulation of the epiglottis and vocal folds. As assessed by EMGs, the RA muscles were normally silent during eupneic breathing. RA EMGs and Pes increased during mechanically-elicited cough. Individual coughs as well as repetitive cough bouts were frequently generated after injury (Fig. 2A). Pes and RA EMGs during coughing were similar to pre-injury recordings. The EMG patterns at all post-injury time points were typical of ballistic-like bursting observed in uninjured animals (Bolser et al., 2000) (Fig. 2B). Moreover, they were present bilaterally. Finally, the peak EMG activities of the LRA and RRA during cough occurred simultaneously and were correlated with increases in Pes. Thus, qualitatively, these general cough characteristics appeared similar to those observed prior to injury. Quantitative assessments below support these observations.

Figure 2.

Cough characteristics. Representative un-filtered and moving average integrated electromyograms of the right rectus abdominis and left rectus abdominis with corresponding esophageal pressures (cmH20) during cough in a cat 13 weeks post-hemisection (A). The single cough, as well as the subsequent bout of coughing, show robust esophageal pressures and EMG activities bilaterally which are similar to those seen in normal cats. Representative unfiltered RA EMGs show the pre-expulsive behavior seen during some coughs at all post-SCI timepoints during the inspiratory phase (B). The duration of pre-expulsive EMG activity was similar to previously reported studies. (C). A prolonged Pes rise time was seen in some coughs at 13wphx compared to other time points. When this prolonged rise time occurred, it was not accompanied by an increase in Pes.

Cough Pes, measured in cmH20, at each time point were: 64.06±39.75 (pre-SCI), 58.38±32.00 (4 wphx), 39.94±25.91 (13 wphx) and 68.93±38.51 (21 wphx). No significant change in the average Pes was seen across time points (p=0.410). In addition, during some individual coughs post-operatively, Pes reached or exceeded 100cm H2O indicating that the injured system was capable of generating the substantial pressures sometimes seen pre-injury, as well as in other reports of normal cats (Bolser et al., 2000). A significant effect of time on Pes rise time was found, F (3, 12) = 4.29, p = 0.028. However, post-hoc Fisher’s LSD tests did not reveal significant differences between any time points. Despite this, a prolonged Pes rise time was present at 13 weeks post-injury during some coughs. When this prolonged rise time occurred, it was manifested without a change in the magnitude of mechanical Pes (Fig. 2C). Average rise times were 0.089±0.02 (pre-SCI), 0.087±0.03 (4 wphx), 0.12±0.02 (13 wphx) and 0.082±0.02 seconds (21 wphx).

Normalized EMG amplitudes during cough showed that the percent of maximal burst of the LRA averaged 70.50±21.70 pre-SCI, 60.55±7.15 at 4 wphx, 72.21±9.18 at 13 wphx, and 70.01±14.53 at 21 wphx. Similarly, the percent of maximal burst of the RRA averaged 78.76±11.36 pre-SCI, 60.64±13.58 at 4 wphx, 71.22±9.71at 13 wphx and 74.85±6.86 at 21 wphx. A two-factor ANOVA revealed no significant change in the average percent of maximum amplitude over time (p=0.67) or between the left and right RA muscles (p=0.587). As with LRA and RRA normalized amplitudes, no significant effects of time (p=0.183), side (0.136) or the interaction of time by side (0.690) were seen for EMG rise times. Average rise times (seconds) for the LRA were 0.111±0.04 pre-SCI, 0.095±0.05 at 4 wphx, 0.159±0.02 at 13 wphx, and 0.139±0.08 at 21wphx and for the RRA were 0.094±0.04 pre-SCI, 0.102±0.06 at 4 wphx, 0.146±0.03 at 13 wphx,, and 0.119±0.08 at 21wphx.

Rectus abdominis EMG activity was observed during the inspiratory phase of coughing in the majority of animals at all time points (Fig. 2B). This muscle activity was termed pre-expulsive because it occurred during the inspiratory phase and before the expulsive cough phase. There was no qualitative change in pre-expulsive activity in the RA EMG at any post-injury time point compared to pre-injury values and the duration of this pre-expulsive activity was similar to the 600–700 ms range reported by Bolser and colleagues (Bolser et al., 2000).

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that expiratory motor drive to abdominal muscles is not significantly impaired during cough in cats that are chronically hemisected in the lower thoracic spinal cord. Furthermore, the mechanical features of the cough reflex as determined from esophageal pressure measurements are similarly resilient. This is the first study to assess the chronic effects of low thoracic hemisection on the cough reflex.

The results of the study may be subject to caveats associated with repeated data collection across time in which EMG electrodes are removed and replaced. The Pes records are independent of electrode placements and provide a constant measurement of mechanics across time points. In contrast to the peak EMG and Pes amplitudes, the rates of rise were not normalized. Placement of the electrodes likely varied within a region of ~1cm, and therefore different motor unit populations were likely sampled at different post-SCI time points. To our knowledge, there is no evidence suggesting regional differences in EMG patterns within a given anterolateral muscle during cough. Additionally, the data collected are of multi-unit EMGs, not single units. This is evident in the intense motor bursts recorded which are consistent with the simultaneous responses of very large groups of motor units.

The regenerative capacity of the central nervous system is limited (Steward et al., 2008). However, following incomplete spinal lesions in humans (Dietz et al., 1998; Dobkin et al., 2007; Fawcett et al., 2007) and animals (Bareyre et al., 2004; Courtine et al., 2005; Courtine et al., 2008; Rossignol et al., 1999; Weidner et al., 2001) some locomotor recovery can occur without apparent intervention. Our studies suggest that the cough motor system shows similar endogenous recovery and/or has substantial preservation of function following a range of incomplete thoracic lesions.

Following injury, function may be mediated through indirect or bypass pathways. Premotor drive to the motoneuron pools of the four primary expiratory muscles arises primarily from bulbospinal neurons in the caudal part of the ventral respiratory column (cVRC), corresponding to the caudal portion of the nucleus retroambigualis and descend into the contralateral ventral column of the lateral spinal cord (Kirkwood 1995; Merrill, 1970). Kirkwood and colleagues (Kirkwood et al., 1988; Schmid et al., 1993) have proposed that spinal interneurons play an important role in mediating this descending expiratory drive. Many of the expiratory-associated thoracic interneurons they identified had crossed axons and spanned multiple segments. They suggested that these crossed interneuronal connections might mediate heterogeneous functions including inhibition of inspiratory thoracic motoneurons during the expiratory phase of breathing and excitation of chest wall motoneurons. It is reasonable that these interneurons may provide a mechanism by which drive from each cVRC is bilaterally represented in the spinal cord. This would enable expiratory cough muscles with motoneurons caudal and ipsilateral to a hemisection to receive cVRC input via multisynaptic connections. Recently, contralaterally projecting cervical interneurons associated with phrenic (respiratory) motoneurons in the rat also have been identified (Lane et al., 2008) suggesting that respiratory-associated interneurons are present at multiple spinal levels in the normal and injured spinal cord. The potential importance of interneurons for recovery also has been reported recently with respect to locomotor recovery (Courtine et al., 2008). Following SCI in the mouse, thoracic interneurons were reported to mediate recovery of basic stepping in the relative absence of direct descending supraspinal connections to the spinal segments containing the hindlimb motoneurons.

Spontaneous plasticity and recovery also has been reported with respect to the respiratory system. Clinically, recovery of respiration does occur, allowing most spinal cord injured individuals to become independent of respiratory support within months after injury (Bluechardt et al., 1992; Linn et al., 2001). However, this recovery is usually incomplete, and many individuals achieving ventilator independence still experience respiratory deficits and impaired cough (Brown et al., 2006).

In the phrenic motor system, it is well established that there is a significant potential for spontaneous recovery and neuroplasticity post-SCI (for reviews see (Lane et al., 2008; Mitchell and Johnson, 2003)). Following upper cervical lateral hemisection, and interruption of inspiratory drive on one side of the spinal cord, the ipsilateral hemiparetic diaphragm spontaneously regains function following contralateral phrenic nerve transection. This injury-induced respiratory plasticity occurs via activation of pre-existing crossed pathways within the spinal cord (Goshgarian and Guth, 1977; Guth, 1976) and is largely serotonin dependent (Hadley et al., 1999; Tai et al., 1997). To our knowledge, only one paper has assessed respiratory function following incomplete experimental thoracic injuries. In this work, recovery of tidal volume and respiratory rate began sometime between 7 and 28 days post-injury in the rat (Teng et al., 1999). Our results demonstrate that a similar potential for recovery and neuroplasticity post-SCI may exist in the cough motor system. Based upon the current results, future studies should assess earlier time points to determine if the cough function seen is due to preservation of function, extensive potential for neuroplasticity, or a combination of both following low thoracic hemisection (Teng et al., 1999).

Upregulation of serotonin has been shown rostral to a complete transection (Shapiro et al., 1995), and several studies suggest that increased expression or activation of serotonin and its receptors may affect the onset and magnitude of respiratory plasticity (Choi et al., 2005; Fuller et al., 2005; Teng et al., 2003). Adenosine receptor activation also may be a key player in respiratory plasticity following SCI (Golder et al., 2008; James and Nantwi, 2006; Nantwi and Goshgarian, 2002). It is feasible that these systems could contribute to plasticity of the cough reflex following SCI. Another possible mechanism supporting the recovery or preservation of cough in our model is muscle-motoneuron reorganization. It clearly has been demonstrated that following incomplete cervical SCI, the partially denervated biceps muscle fibers are reinnervated by collateral sprouting of the remaining injured motoneurons (Nakamura et al., 1997). Remaining motoneurons within the rectus abdominis motoneuron pool may have this same potential for reorganization. Many possible mechanisms may underlie neuroplasticity within the cough system, peripherally and centrally. These may include plasticity in the sensory afferent fibers, changes in the release of neurochemicals at the central terminals of vagal afferent neurons such as glutamate and Substance P, or changes in synaptic input (for review see (Bonham et al., 2004)).

Although reports are mixed, the clinical literature indicates that individuals with thoracic spinal injuries generally maintain inspiratory capabilities but experience expiratory dysfunction due to partial paralysis (Hemingway et al., 1958) and atrophy (Davis, 1993; Kern et al., 2008) of the abdominal musculature. A variety of expiratory muscle conditioning or training techniques have been reported to improve some expiratory functions following SCI in humans (for review see (Van Houtte et al., 2006)). These include high frequency magnetic stimulation, surface muscle stimulation, and electrical spinal cord stimulation (Jaeger et al., 1993; Lee et al., 2008; Lim et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2001; Linder, 1993). Significant atrophy of the expiratory muscles along with decreased functional capacity also has been shown in the cat following a T6 complete spinal transection (Kowalski et al., 2007). Further, electrical stimulation of the spinal cord at T10 for 6 months following T6 transection appears to prevent the muscle atrophy and support greater expiratory function (DiMarco and Kowalski, 2008). Although specific conditioning of the abdominal muscles with respect to cough or other respiratory functions was not done in the current study, all cats were extensively trained on a variety of locomotor tasks 5×/week. Training involved treadmill walking as well as crossing of simple and challenging runways (for examples see (Tester and Howland, 2008)). Substantial evidence suggests that locomotor training can improve hindlimb/lower extremity motor functions post-SCI in animals and humans respectively (Behrman et al., 2006; Edgerton et al., 2004; Frigon and Rossignol, 2006; Thomas and Gorassini, 2005). Other studies indicate that it improves abdominal expiratory muscle activity in intact subjects (Halseth et al., 1995; Powers et al., 1997; Powers et al., 1992; Uribe et al., 1992) and that locomotor and respiratory rhythms are coupled (Kawahara et al., 1989; Kawahara et al., 1989; Romaniuk et al., 1994). Further, voluntary exercise has been shown to increase the production of several neurotrophins (Gomez-Pinilla et al., 2002; Ying et al., 2003) which may play significant roles in motor recovery and synaptic plasticity post-SCI (Ying et al., 2008). Although the effects of locomotor training on cough specifically have not been tested, the combined literature suggests it may have contributed to the substantial cough function seen in the current study. It will be important to test the effects of locomotor training on cough function following SCI in future studies.

Even with complete disruption of the brainstem descending expiratory projections to the left side of the spinal cord below T9, cats in the current study showed substantially normal cough function and abdominal muscle activity bilaterally. Although only one of the four primary expiratory muscles was assessed (rectus abdominis), it is unlikely that its normal activity level alone would be sufficient to generate the Pes seen post-injury in our animals. The pressures generated at all post-injury time points were not significantly different from pre-injury values. All four anterolateral abdominal muscles undergo similar increases in EMG activity, peaking within ~35ms of each other, during cough in normal anesthetized cats (Bolser et al., 2000). This suggests that the other three abdominal muscles also were contributing to force generation.

Despite the fact that cough dysfunction is associated with significant morbidity in the human population following SCI, few experimental animal studies address this critical topic. In addition to contributing to the currently small base of knowledge in this area, the present work identifies several immediate areas of particular interest for future study. These include the importance of assessing earlier time points post-injury to determine if cough function is interrupted acutely in this model. The results of such studies will suggest whether the substantial function in the abdominal motor system seen by 4 weeks post- hemisection is supported by the partial sparing of bilaterally represented substrates normally found in the spinal cord or whether it is dependent upon plasticity of descending and/or intraspinal circuitry. Further, the importance of the pre- and post-locomotor training used in the current study is unknown. The growth factors that increase with voluntary exercise may impact synaptic plasticity pre- or post-injury and affect outcomes. These studies, and others, are critical for determining appropriate models for assessing cough following SCI and identifying mechanisms underlying any recovery of cough function.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH NINDS RO1 NS050699, HL70125, T32 HD043730, the Daniel Heumann Fund, and the Department of Veterans Affairs, RR&D Center funding. We thank Jimmy Lapnawan (biological technician) and Wilbur O'Steen (laboratory manager) who assisted with data collection and animal procedures throughout the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bareyre FM, Kerschensteiner M, Raineteau O, Mettenleiter TC, Weinmann O, Schwab ME. The injured spinal cord spontaneously forms a new intraspinal circuit in adult rats. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nn1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman AL, Bowden MG, Nair PM. Neuroplasticity after spinal cord injury and training: an emerging paradigm shift in rehabilitation and walking recovery. Phys. Ther. 2006;86:1406–1425. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20050212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluechardt MH, Wiens M, Thomas SG, Plyley MJ. Repeated measurements of pulmonary function following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1992;30:768–774. doi: 10.1038/sc.1992.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC. Fictive cough in the cat. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991;71:2325–2331. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC, Aziz SM, DeGennaro FC, Kreutner W, Egan RW, Siegel MI, Chapman RW. Antitussive effects of GABAB agonists in the cat and guinea-pig. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1993;110:491–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13837.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolser DC, Reier PJ, Davenport PW. Responses of the anterolateral abdominal muscles during cough and expiratory threshold loading in the cat. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000;88:1207–1214. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham AC, Sekizawa SI, Joad JP. Plasticity of central mechanisms for cough. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;17:453–457. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2004.09.008. discussion 469–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, DiMarco AF, Hoit JD, Garshick E. Respiratory dysfunction and management in spinal cord injury. Respir. Care. 2006;51:853–868. discussion 869–870. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Liao WL, Newton KM, Onario RC, King AM, Desilets FC, Woodard EJ, Eichler ME, Frontera WR, Sabharwal S, Teng YD. Respiratory abnormalities resulting from midcervical spinal cord injury and their reversal by serotonin 1A agonists in conscious rats. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:4550–4559. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5135-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Roy RR, Raven J, Hodgson J, McKay H, Yang H, Zhong H, Tuszynski MH, Edgerton VR. Performance of locomotion and foot grasping following a unilateral thoracic corticospinal tract lesion in monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Brain. 2005;128:2338–2358. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtine G, Song B, Roy RR, Zhong H, Herrmann JE, Ao Y, Qi J, Edgerton VR, Sofroniew MV. Recovery of supraspinal control of stepping via indirect propriospinal relay connections after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 2008;14:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nm1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GM. Exercise capacity of individuals with paraplegia. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993;25:423–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JN, Plum F. Separation of descending spinal pathways to respiratory motoneurons. Exp Neurol. 1972;34:78–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(72)90189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V, Wirz M, Curt A, Colombo G. Locomotor pattern in paraplegic patients: training effects and recovery of spinal cord function. Spinal Cord. 1998;36:380–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMarco AF, Kowalski KE. Effects of chronic electrical stimulation on paralyzed expiratory muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2008;104:1634–1640. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01321.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobkin B, Barbeau H, Deforge D, Ditunno J, Elashoff R, Apple D, Basso M, Behrman A, Harkema S, Saulino M, Scott M. The evolution of walking-related outcomes over the first 12 weeks of rehabilitation for incomplete traumatic spinal cord injury: the multicenter randomized Spinal Cord Injury Locomotor Trial. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2007;21:25–35. doi: 10.1177/1545968306295556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgerton VR, Tillakaratne NJ, Bigbee AJ, de Leon RD, Roy RR. Plasticity of the spinal neural circuitry after injury. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;27:145–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D, Bartlett PF, Blight AR, Dietz V, Ditunno J, Dobkin BH, Havton LA, Ellaway PH, Fehlings MG, Privat A, Grossman R, Guest JD, Kleitman N, Nakamura M, Gaviria M, Short D. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:190–205. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigon A, Rossignol S. Functional plasticity following spinal cord lesions. Prog Brain Res. 2006;157:231–260. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(06)57016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller DD, Baker-Herman TL, Golder FJ, Doperalski NJ, Watters JJ, Mitchell GS. Cervical spinal cord injury upregulates ventral spinal 5-HT2A receptors. J. Neurotrauma. 2005;22:203–213. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder FJ, Ranganathan L, Satriotomo I, Hoffman M, Lovett-Barr MR, Watters JJ, Baker-Herman TL, Mitchell GS. Spinal adenosine A2a receptor activation elicits long-lasting phrenic motor facilitation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2033–2042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3570-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla F, Ying Z, Roy RR, Molteni R, Edgerton VR. Voluntary exercise induces a BDNF-mediated mechanism that promotes neuroplasticity. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2187–2195. doi: 10.1152/jn.00152.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goshgarian HG, Guth L. Demonstration of functionally ineffective synapses in the guinea pig spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 1977;57:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(77)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth L. Functional plasticity in the respiratory pathway of the mammalian spinal cord. Exp. Neurol. 1976;51:414–420. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(76)90265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley SD, Walker PD, Goshgarian HG. Effects of serotonin inhibition on neuronal and astrocyte plasticity in the phrenic nucleus 4 h following C2 spinal cord hemisection. Exp. Neurol. 1999;160:433–445. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halseth AE, Fogt DL, Fregosi RF, Henriksen EJ. Metabolic responses of rat respiratory muscles to voluntary exercise training. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995;79:902–907. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.3.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemingway A, Bors E, Hobby RP. An investigation of the pulmonary function of paraplegics. J. Clin. Invest. 1958;37:773–782. doi: 10.1172/JCI103663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iscoe S. Control of abdominal muscles. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;56:433–506. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger RJ, Turba RM, Yarkony GM, Roth EJ. Cough in spinal cord injured patients: comparison of three methods to produce cough. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1993;74:1358–1361. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90093-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James E, Nantwi KD. Involvement of peripheral adenosine A2 receptors in adenosine A1 receptor-mediated recovery of respiratory motor function after upper cervical spinal cord hemisection. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2006;29:57–66. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2006.11753857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara K, Kumagai S, Nakazono Y, Miyamoto Y. Coupling between respiratory and stepping rhythms during locomotion in decerebrate cats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989;67:110–115. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.67.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara K, Nakazono Y, Yamauchi Y, Miyamoto Y. Coupling between respiratory and locomotor rhythms during fictive locomotion in decerebrate cats. Neurosci. Lett. 1989;103:326–330. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern H, Hofer C, Modlin M, Mayr W, Vindigni V, Zampieri S, Boncompagni S, Protasi F, Carraro U. Stable muscle atrophy in long-term paraplegics with complete upper motor neuron lesion from 3- to 20-year SCI. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:293–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA. Synaptic excitation in the thoracic spinal cord from expiratory bulbospinal neurones in the cat. J. Physiol. 1995;484(Pt 1):201–225. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkwood PA, Munson JB, Sears TA, Westgaard RH. Respiratory interneurones in the thoracic spinal cord of the cat. J. Physiol. 1988;395:161–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski KE, Romaniuk JR, DiMarco AF. Changes in expiratory muscle function following spinal cord section. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:1422–1428. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00870.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, Fuller DD, White TE, Reier PJ. Respiratory neuroplasticity and cervical spinal cord injury: translational perspectives. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane MA, White TE, Coutts MA, Jones AL, Sandhu MS, Bloom DC, Bolser DC, Yates BJ, Fuller DD, Reier PJ. Cervical prephrenic interneurons in the normal and lesioned spinal cord of the adult rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008;511:692–709. doi: 10.1002/cne.21864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BB, Boswell-Ruys C, Butler JE, Gandevia SC. Surface functional electrical stimulation of the abdominal muscles to enhance cough and assist tracheostomy decannulation after high-level spinal cord injury. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31:78–82. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2008.11753985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Gorman RB, Saboisky JP, Gandevia SC, Butler JE. Optimal electrode placement for noninvasive electrical stimulation of human abdominal muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2007;102:1612–1617. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00865.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin VW, Hsiao IN, Zhu E, Perkash I. Functional magnetic stimulation for conditioning of expiratory muscles in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001;82:162–166. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder SH. Functional electrical stimulation to enhance cough in quadriplegia. Chest. 1993;103:166–169. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn WS, Spungen AM, Gong H, Jr., Adkins RH, Bauman WA, Waters RL. Forced vital capacity in two large outpatient populations with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:263–268. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill EG. The lateral respiratory neurones of the medulla: their associations with nucleus ambiguus, nucleus retroambigualis, the spinal accessory nucleus and the spinal cord. Brain Res. 1970;24:11–28. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90271-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill EG. Finding a respiratory function for the medullary respiratory neurons, Essays on the nervous system. Oxford Eng.: Clarendon Press; 1974. p. viii. 511. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AD. Localization of motoneurons innervating individual abdominal muscles of the cat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;256:600–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell GS, Johnson SM. Neuroplasticity in respiratory motor control. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;94:358–374. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00523.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Fujimura Y, Yato Y, Watanabe M. Muscle reorganization following incomplete cervical spinal cord injury in rats. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:752–756. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nantwi KD, Goshgarian HG. Actions of specific adenosine receptor A1 and A2 agonists and antagonists in recovery of phrenic motor output following upper cervical spinal cord injury in adult rats. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2002;29:915–923. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SK, Coombes J, Demirel H. Exercise training-induced changes in respiratory muscles. Sports Med. 1997;24:120–131. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199724020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers SK, Grinton S, Lawler J, Criswell D, Dodd S. High intensity exercise training-induced metabolic alterations in respiratory muscles. Respir Physiol. 1992;89:169–177. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romaniuk JR, Kasicki S, Kazennikov OV, Selionov VA. Respiratory responses to stimulation of spinal or medullary locomotor structures in decerebrate cats. Acta. Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars) 1994;54:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossignol S, Drew T, Brustein E, Jiang W. Locomotor performance and adaptation after partial or complete spinal cord lesions in the cat. Prog. Brain. Res. 1999;123:349–365. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62870-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid K, Kirkwood PA, Munson JB, Shen E, Sears TA. Contralateral projections of thoracic respiratory interneurones in the cat. J. Physiol. 1993;461:647–665. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S, Kubek M, Siemers E, Daly E, Callahan J, Putty T. Quantification of thyrotropin-releasing hormone changes and serotonin content changes following graded spinal cord injury. J. Surg. Res. 1995;59:393–398. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1995.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steward O, Zheng B, Tessier-Lavigne M, Hofstadter M, Sharp K, Yee KM. Regenerative growth of corticospinal tract axons via the ventral column after spinal cord injury in mice. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6836–6847. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5372-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Q, Palazzolo KL, Goshgarian HG. Synaptic plasticity of 5-hydroxytryptamine-immunoreactive terminals in the phrenic nucleus following spinal cord injury: a quantitative electron microscopic analysis. J. Comp. Neurol. 1997;386:613–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YD, Bingaman M, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Pace PP, Gillis RA, Wrathall JR. Serotonin 1A receptor agonists reverse respiratory abnormalities in spinal cord-injured rats. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:4182–4189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04182.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng YD, Mocchetti I, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Gillis RA, Wrathall JR. Basic fibroblast growth factor increases long-term survival of spinal motor neurons and improves respiratory function after experimental spinal cord injury. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:7037–7047. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-16-07037.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester NJ, Howland DR. Chondroitinase ABC improves basic and skilled locomotion in spinal cord injured cats. Exp. Neurol. 2008;209:483–496. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SL, Gorassini MA. Increases in corticospinal tract function by treadmill training after incomplete spinal cord injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2844–2855. doi: 10.1152/jn.00532.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomori Z, Widdicombe JG. Muscular, bronchomotor and cardiovascular reflexes elicited by mechanical stimulation of the respiratory tract. J. Physiol. 1969;200:25–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe JM, Stump CS, Tipton CM, Fregosi RF. Influence of exercise training on the oxidative capacity of rat abdominal muscles. Respir. Physiol. 1992;88:171–180. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtte S, Vanlandewijck Y, Gosselink R. Respiratory muscle training in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Respir. Med. 2006;100:1886–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner N, Ner A, Salimi N, Tuszynski MH. Spontaneous corticospinal axonal plasticity and functional recovery after adult central nervous system injury. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98:3513–3518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051626798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, Gomez-Pinilla F. Voluntary exercise increases neurotrophin-3 and its receptor TrkC in the spinal cord. Brain Res. 2003;987:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03258-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Z, Roy RR, Zhong H, Zdunowski S, Edgerton VR, Gomez-Pinilla F. BDNF-exercise interactions in the recovery of symmetrical stepping after a cervical hemisection in rats. Neuroscience. 2008;155:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]