Abstract

We studied separately the effects of weight-loss by dieting or by running on apolipoprotein (apo) A-I, apo A-II, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) subfractions in sedentary, moderately overweight men assigned at random into three groups: exercise without calorie restriction, calorie restriction without exercise, and control. The absorbance of protein-stained polyacrylamide gradient gels was used as an index of mass concentrations for five HDL subclasses that have been identified by their particle sizes: HDL3c (7.2 to 7.8 nm), HDL3b (7.8 to 8.2 nm), HDL3a (8.2 to 8.8 nm), HDL2a (8.8 to 9.7 nm), and HDL2b (9.7 to 12.8 nm). During the l-year trial, the exercisers ran (mean ± SD) 15.8 ± 8.1 km/wk, and the dieters reported eating 340±71 fewer calories per day than at baseline. Total body weight and fat weight were both reduced significantly more in dieters (−7.2 ± 4.1 and −6.2 ± 4.1 kg, respectively) and in exercisers (−4.0 ± 3.9 and −4.6 ± 3.5 kg) than in controls (0.6 ± 3.7 and −0.7 ± 2.7 kg). As compared with mean changes in controls, exercisers and dieters each decreased HDL3b and increased HDL2b. Exercisers also significantly increased plasma apo A-I concentrations. Analysis of covariance was used to statistically adjust the mean lipoprotein changes for the effects of weight-loss. The adjustment eliminated the significant reductions in HDL3b and the significant increases in HDL2b in exercisers and dieters, and it eliminated the significant increase in apo A-I in exercisers. When adjusted, the dieters’ mean changes in HDL2b had significantly decreased relative to those of both exercisers and controls. These results suggest that the changes in HDL3b, HDL2b, and apo A-I during 12 months of exercise could be due to metabolic changes associated with exercise-induced weight-loss. Reduced calorie flux or other factors appear to attenuate the increase in HDL2b and apo A-I during diet-induced weight-loss.

Running increases the plasma mass and cholesterol concentrations of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)2 in men [1–3]. The HDL3 response to running is less clear, with some studies showing an increase and other studies showing either a decrease or no change [1,2,4]. HDLs may be further divided into two HDL2 and three HDL3 subclasses by nondenaturing polyacrylamide gradient gel electrophoresis [5]. They are defined by their estimated particle diameters: HDL3c (7.2 to 7.8 nm), HDL3b (7.8 to 8.2 nm), HDL3a (8.2 to 8.8 nm), HDL2a (8.8 to 9.7 nm), and HDL2b (9.7 to 12.9 nm) [5]. These HDL subclasses show relationships to other lipoprotein variables that suggest that HDL2a and HDL2b are inversely related, and HDL3b is positively related to coronary heart disease risk [6]. To our knowledge, the effects of exercise or diet on HDL subclass measurements by gradient gel electrophoresis have not been previously reported.

This report describes the effects of diet-induced weight-loss and exercise-induced weight-loss on plasma apolipoprotein (apo) A-I and apo A-II concentrations, and on protein-stained HDL subclasses as identified by electrophoresis. These were measured as part of a l-year, randomized, controlled clinical trial of initially sedentary overweight men [1,2]. We have previously reported that both interventions significantly increased plasma HDL2 concentrations as compared with the control condition [2]. The increases were significant both during active weight-loss (7-month) and after weight-loss had stabilized for 6 weeks (12-month). Statistical analyses showed that the increases in the exercisers’ and dieters’ HDL2 are largely attributable to weight-loss. This finding is important because it challenges the belief that the elevated HDL concentrations of runners are principally due to muscular adaptations to exercise [3,7–9].

This report also tests for a potential source of bias in cross-sectional studies of runners. Many cross-sectional studies show that HDL levels in runners are only weakly related to body weight [9]. However, these analyses are based on the runners’ current weight rather than on the amount of weight they lost since starting to run. A recent review of published cross-sectional studies suggests that weight-loss since starting to run appears to explain most of the published HDL-cholesterol differences between runners and sedentary men [10]. This conclusion is consistent with the report that previously obese runners have higher HDL-cholesterol levels than runners of comparable leanness who were never obese [11]. Current weight was unrelated to HDL in these men. In the present study, we use multiple regression to test which of two variables is the better predictor of the runners’ final apolipoprotein and HDL subclass measurements: change in weight since starting to run, or weight at the time of the final HDL measurement.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects and Laboratory Measurements

As described previously, we recruited 155 sedentary men aged 30 to 59 years who were 20% to 60% over Metropolitan ideal weight, nonsmokers, not on medication that might affect lipid metabolism, nonhypertensive (blood pressure < 160/100 mm Hg), and nonhyperlipidemic (plasma total cholesterol < 8.28 mmol/L and triglycerides < 5.65 mmol/L). After their baseline evaluation, these men were assigned at random into one of three experimental conditions: diet (calorie restriction without increasing exercise); exercise (increase in physical activity, primarily running, with no change in diet); and control (no change in diet or exercise). During the last 6 weeks of the trial, the dieters stabilized their weight-loss by adjusting their energy intake, and the exercisers stabilized their weight-loss by adjusting their exercise level while keeping energy intake constant.

At baseline, 7 months, and 1 year, the men reported to our clinic in the morning, after having abstained for 12 to 16 hours from all food intake and any vigorous activity. We estimated body compositions by hydrostatic weighing and maximal oxygen uptakes in mL/kg/min (VO2 max) by recording gas exchange during treadmill tests to exhaustion [1]. Energy intakes were estimated by computer analysis of the food diaries maintained by the participants over a 7-day diet period [12]. The runners recorded their exercise duration and frequency in diaries. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Results are usually displayed for changes in BMI, rather than for changes in percent body fat, because its regression and correlation coefficients are expected to be less biased by measurement error [13].

Venous blood was collected through a butterfly catheter into a syringe, with the subject in a supine position for less than 10 minutes. The blood was immediately transferred into tubes containing sodium EDTA (1 mg/L). HDL-cholesterol was measured by dextran sulfate-magnesium precipitation, followed by enzymatic determination of cholesterol [14]. These measurements were consistently in control as monitored by the Lipid Standardization Program of the Center for Disease Control and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. HDL3-cholesterol was determined by a dextran sulfate-magnesium precipitation method, and HDL2-cholesterol was calculated as the difference between HDL cholesterol and HDL3-cholesterol [15]. Plasma apo A-I and A-II concentrations were determined by radialimmunodiffusion [16]. HDL-mass concentrations were determined by analytic ultracentrifugation [17].

Electrophoresis of HDL in the ultracentrifuged d ≤ 1.20 g/mL fraction was performed on a Pharmacia Electrophoresis Apparatus (GE 4-B) using slab gradient gels (PAA 4/30, Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), as described by Blanche et al [5]. The protein-stained gradient gels were scanned with a model RPT densitometer (Transidyne, Ann Arbor, MI) at a wavelength of 603 nm. A mixture of four globular proteins (HMW Calibration Kit, Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) was run on the central lane to calibrate for particle size. Thyroglobulin was added to each HDL sample. The migration distances (Rf) for HDL were measured relative to the Rf of the peak of bovine serum albumin, one of the protein standards. The thyroglobulin peak was identified for each sample and assigned the Rf value for thyroglobulin on the calibration lane. Calculus was used to transform the HDL distributions from the Rf scale to the particle diameter scale [18]. The height of the distribution as measured by absorbance at each diameter value was then determined by interpolation for each 0.01 nm value between 7.2 and 12.0 nm. We did not standardize the gradient gel profiles for the area of the thyroglobulin peak because the adjustment was found to increase the sample variance.

Statistics

ANOVA was used to assign significance levels to the differences between the exercise, diet, and control groups. Pearson correlation coefficients and linear regression describe the pair-wise associations between lipoprotein mass concentrations, weight-loss, distance run per week, maximum aerobic capacity (VO2 max), and energy intake. Analysis of covariance was used to adjust changes in lipoproteins for changes in percent body fat or BMI. Adjustment by this method assumes that the relationship between the dependent variable and covariate is the same within each group. The equality of the regression slopes was tested prior to adjustment.

Correlation coefficients and significance levels from regression analyses and ANOVA are unaffected by conversions involving the addition and/or multiplication of numerical constants. Conversion from absorbance to plasma concentration is therefore not required for comparing protein-stained HDL levels. The statistical tests used in this report are invariant to translations of scale or location. Therefore, the statistics and significance levels for absorbance will be identical to those based on plasma concentrations. Moreover, differences in chromogenicity by particle diameter will not affect the pattern of correlations over the HDL distribution because the conversion factors can be different at each diameter value. The significance levels presented in the figures and tables were further verified by Spearman’s correlations and Wilcoxon two-sample sign rank tests. Nonparametric statistical tests of the protein-stained absorbance will be identical to those based on the unknown plasma concentrations, provided that ordering the gels from lowest to highest optical density is the same as ordering the gels from lowest to highest plasma concentrations (i.e., monotonic transformations).

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of each study group are described by Wood et al [1]. During the l-year trial, the exercisers ran (mean ± SD) 15.6 ± 9.1 km/wk, and the dieters reported eating 340 ± 71 kcal less than they had eaten at baseline. Total body weight was reduced significantly more in exercisers (−4.0 ± 3.9 kg) and dieters (−7.2 ± 4.1 kg) than in controls (0.6 ± 3.7 kg). The loss of weight was primarily due to reductions in fat body mass in exercisers (−4.6 ± 3.5 kg) and dieters (−6.2 ± 4.1 kg). Lean body mass decreased significantly more in dieters (−1.2 ± 2.4 kg) than in exercisers (−0.1 ± 2.1 kg) or controls (1.3 ± 2.0 kg). Changes in lipids, lipoprotein cholesterol, and lipoprotein mass measurements during the trial are described by Wood et al [1] and Williams et al [2].

Apo A-I and A-II

Plasma apo A-I and A-II concentrations were measured at all three clinic visits in 46 exercisers, 42 dieters, and 42 controls. Baseline apo A-I concentrations were similar in exercisers (137.0 ± 21.6 mg/dL), dieters (138.6 ± 21.0 mg/dL), and controls (135.3 ± 21.9 mg/dL). Baseline apo A-II concentrations were slightly higher in dieters (32.9 ± 5.2 mg/dL) than in exercisers (30.4 ± 6.7 mg/dL) or controls (30.1 ± 4.5 mg/dL).

Mean differences between groups

Apo A-I appears to increase during exercise-induced weight-loss. Table 1 shows that by 12 months, apo A-I had increased significantly more in exercisers than in controls, but not more than in dieters. The results were statistically adjusted to equivalent change in BMI by analysis of covariance. This adjustment (1) eliminated the significant difference between exercisers and controls at 12 months, and (2) created significant differences between the exercisers and dieters after both 7 and 12 months. Therefore, the increase in apo A-I during exercise can be attributed to weight-loss. Reduced caloric flux or other factors could attenuate the increase in apo A-I associated with diet-induced weight-loss. Although apo A-II concentrations decreased significantly less in exercisers than in dieters, this difference could be, in part, an artifact of the dieters’ high baseline value.

Table 1.

Changes in apo A-l and A-II concentrations in exercisers, dieters, and controls

| Controls (Mean±SE) | Exercise-Control (Difference±SE) | Diet-Control (Difference±SE) | Exercise-Diet (Difference±SE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo A-I (mg/dL) | ||||

| Δ7 months | ||||

| Unadjusted | −2.48 ± 1.90 | 2.45 ± 3.25 | −3.04 ± 3.33 | 5.49 ± 3.27 |

| Δ BMI adjusted | −0.62 ± 2.81 | 1.09 ± 3.49 | −6.86 ± 4.73 | 7.95 ± 3.80* |

| Δ12 Months | ||||

| Unadjusted | −5.67 ± 1.90 | 8.49 ± 3.07* | 4.06 ± 3.14 | 4.43 ± 3.09 |

| Δ BMI adjusted | −1.76 ± 2.54 | 4.09 ± 3.35 | −3.32 ± 3.99 | 7.42 ± 3.18* |

| Apo A-II (mg/dL) | ||||

| Δ7 Months | ||||

| Unadjusted | −0.58 ± 0.61 | −0.20 ± 0.85 | −2.30 ± 0.87† | 2.10 ± 0.85* |

| Δ BMI adjusted | −1.71 ± 0.71 | 0.74 ± 0.89 | 0.17 ± 1.20 | 0.57 ± 0.97 |

| Δ12 Months | ||||

| Unadjusted | 0.94 ± 0.61 | 1.45 ± 0.89 | −1.16 ± 0.91 | 2.61 ± 0.90† |

| Δ BMI adjusted | −1.61 ± 0.75 | 2.21 ± 0.99* | 0.12 ± 0.18 | 2.09 ± 0.94* |

Signficance levels by analysis of variance or covariance:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01.

Associations with changes in weight, adiposity calorie intake, and distance ran

Correlations within the exercise group suggest that the exercise intervention produced changes in apo A-I concentrations. Table 2 presents the within-group correlations. Increases in apo A-I concentrations were associated with the exercisers’ running distance, loss of weight (BMI) and percent body fat, increased calorie intake, and increased fitness (i.e., maximum aerobic capacity and treadmill test duration). Decreased apo A-II concentrations were associated with the exercisers’ weight-loss, extended treadmill test duration, and increased calorie intake (7-month only). The correlations between changes in calorie intake and changes in apo A-II are significantly different in exercisers (negative correlations) and dieters (positive correlations).

Table 2.

Correlational analyses of changes in apo A-l and A-II concentrations in exercisers, dieters, and controls

| ΔApo A-I | ΔApo A-II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Diet | Exercise | Control | Diet | Exercise | |

| BMI | ||||||

| Δ7 months | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.24 | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.44† |

| Δ12 months | −0.04 | −0.25 | −0.42† | 0.21 | −0.08 | 0.30* |

| Percent body fat | ||||||

| Δ7 months | 0.00 | −0.23 | −0.32* | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.20 |

| Δ12 months | 0.01 | −0.21 | −0.36* | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.18 |

| Calorie intake | ||||||

| Δ7 months | 0.20 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.29 | −0.30* |

| Δ12 months | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.45† | 0.06 | 0.34* | −0.16 |

| Maximum aerobic capacity | ||||||

| Δ12 months | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.36* | 0.00 | 0.20 | −0.09 |

| Treadmill test duration | ||||||

| Δ12 months | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.33* | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.37* |

| Distance run | ||||||

| 0 to 7 months | 0.32* | −0.11 | ||||

| 0 to12 months | 0.39† | −0.20 | ||||

P < .05,

P < 0.01

Regression analysis of weight lost and post-treatment weight

Table 3 shows that apo A-I concentrations in 46 exercisers were more strongly related to the amount of weight lost than the leanness achieved. The table presents multiple linear regression for predicting posttreatment apo A-I (the dependent variable) from change in BMI since starting the trial (the independent variable representing the amount of weight lost), and post-treatment BMI (the independent variable representing the leanness achieved). Analyses are also presented for HDL2-cholesterol and HDL2 mass for comparison. At the end of 7 months of running, plasma apo A-I, HDL2-cholesterol, and HDL2-mass were more strongly related to changes in BMI between baseline and 7 months than to BMI at 7 months. Plasma apo A-I, HDL2-cholesterol, and HDL2-mass concentrations at 12 months were also more strongly related to changes in BMI between baseline and 12 months than to BMI at 12 months.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analyses (coefficients ± SE) showing that at end of 7-month and 12-month running programs, apo A-I and HDL2 concentrations were more strongly related to weight-loss than to leanness achieved.

| Dependent Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo A-I | Apo A-II | HDL2-cholesterol | HDL2-mass | |

| Dependent variable (mg/dL) measured cross-sectionally at end of 7-months training | ||||

| Intercept | 62.06 ± 41.57 | 31.32 ± 13.97 | 19.26 ± 19.70 | 107.55 ± 109.65 |

| Change in BMI between baseline and 7 mo (mg/dL per Δ kg/m2) | −11.87 ± 4.84* | −0.61 ± 1.24 | −5.58 ± 1.75† | −25.29 ± 9.75* |

| BMI at 7 mo (mg/dL per kg/m2) | 2.32 ± 1.86 | −0.08 ± 0.48 | −0.53 ± 0.67 | −3.17 ± 3.75 |

| Variance explained | 12.3% | 1.0% | 27.6% | 21.6% |

| Dependent variable (mg/dL) measured cross-sectionally at end of 12-months training | ||||

| Intercept | 102.70 ± 57.28 | 29.04 ± 14.71 | 14.80 ± 17.52 | 49.87 ± 92.38 |

| Change in BMI between baseline and 12 mo (mg/dL per Δ kg/m2) | −10.49 ± 4.29* | −0.77 ± 1.10 | −3.10 ± 1.32* | −15.18 ± 6.95* |

| BMI at 12 mo (mg/dL per kg/m2) | 0.85 ± 1.94 | 0.03 ± 0.50 | −0.31 ± 0.59 | −1.00 ± 3.10 |

| Variance explained | 16.7% | 1.8% | 26.4% | 21.7% |

Significance levels from the regression coefficients:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.0l.

Gradient Gel Electrophoresis of Protein-Stained HDL

We did not begin to collect the gradient gel data until after the start of the trial. Complete measurements were obtained in 35 exercisers, 31 dieters, and 31 controls. At baseline, men with gradient gel data were not significantly different from men without gradient gel data (i.e., P > 0.10) for BMI (29.40 ± 2.15 vs. 29.40 ± 2.53 kg/m2, respectively), HDL2-mass (24.9 ± 25.8 v 23.8 ± 25.6 mg/dL), HDL3-mass (212.8 ± 36.7 vs. 211.4 ± 39.2 mg/dL), apo A-I (139.3 ± 21.3 vs. 132.2 ± 22.7 mg/dL), or apo A-II (31.6 ± 5.5 vs. 29.8 ± 6.0 mg/dL) concentrations. During the trial, the 35 exercisers ran 15.5 ± 8.7 km/wk, and the 31 dieters ate 318 ± 460 fewer kilocalories than at baseline. These findings are similar to those of the complete sample. Moreover, as in the total sample, total body weight was reduced significantly more in the 31 dieters (−2.31 ± 1.34 kg) and 35 exercisers (−1.44 ± 1.03 kg) than in the 31 controls (0.21 ± 1.07 kg).

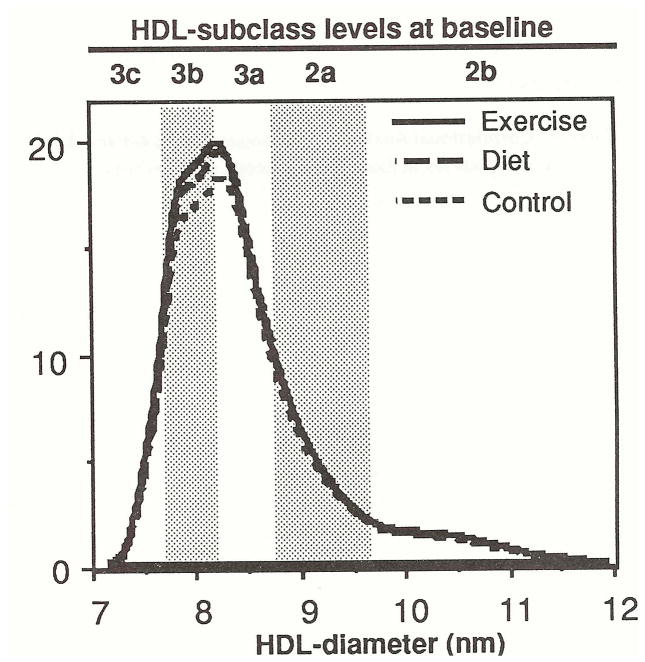

Figure 1 shows that the three groups were well matched at baseline for protein-stained HDL levels. The mean distribution for each group was created by averaging the heights of the individual participants’ distributions at each diameter value. There were no significant group differences at baseline for any diameter value. The proportion of men having a predominant HDL3b peak (i.e., the mode of their HDL distribution between 7.8 and 8.2 nm) also was not significantly different among exercisers (45.7%), dieters (45.2%), and controls (35.5%).

Fig 1.

Mean levels of protein-stained HDL by particle diameter in 35 exercisers, 31 dieters, and 31 controls at baseline. The approximate size intervals for the HDL3c HDL3b HDL3a HDL2a, and HDL2b, subclasses are shown [5]. There were no significant mean differences between groups at any diameter value.

Mean differences between groups

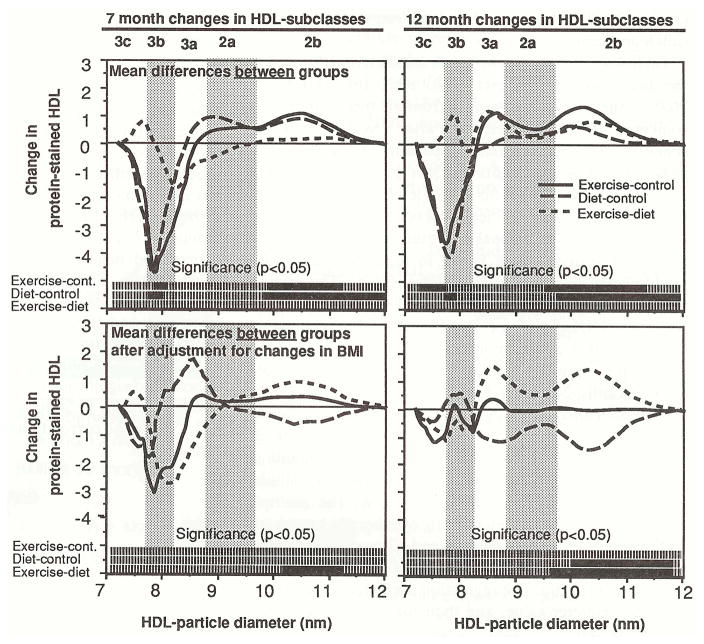

Figure 2 shows that weight-loss by exercise or by diet promoted significant decreases within HDL3c/3b and significant increases within HDL2b. This resulted in a shift towards larger HDL. The mean differences for changes in protein-stained HDL during active weight-loss (7 months) and after weight-loss had stabilized (12 months) are presented. The bars located at the bottom of each graph designate the diameter ranges that exhibit significant (solid bars) and nonsignificant (broken bars) differences between groups. As compared with controls, levels within HDL3b and HDL3c decreased significantly in exercisers after 7 months (significant for 7.79 to 7.99 nm) and 12 months (7.26 to 7.73 nm), and in dieters after 7 months (7.73 to 7.92 nm) and 12 months (7.54 to 7.88 nm). HDL2b increased in exercisers at 7 months (9.83 to 11.09 nm) and 12 months (9.57 to 11.44 nm), and in dieters after 7 months (9.77 to 11.84 nm). The results are similar for HDL measured during active weight-loss (7 months) and after weight stabilization (12 months).

Fig 2.

Differences between exercisers and controls, dieters and controls, and exercisers and dieters for 7-month and 12-month changes in HDL-protein by particle diameter. The men were actively losing weight at 7 months, and had stabilized their weight loss at 12 months. The bars at the bottom of each graph give the statistical significance. Solid bars designate significance (P<0.05), and broken bars designate nonsignificance. Mean differences between groups are also presented after adjustment for changes in BMI by analysis of covariance.

The exercisers’ and the dieters’ increases in HDL2b, and their decreases in HDL3b/3c, can be largely ascribed to weight-loss. Adjustment for change in BMI by analysis of covariance eliminated the exercisers’ increases in HDL2b at 7 months and 12 months, and the dieters’ increases in HDL2b at 7 months. Reductions in HDL3c/3b in exercisers and dieters were also eliminated by adjustment for changes in BMI.

Analysis of covariance suggests that when adjusted to an equivalent change in BMI, the increases within HDL2b were greater in exercisers than in dieters after 7 months (mean significance level, P = .04 for HDL protein between 10.21 and 11.36 nm) and 12 months (mean significance level, P = 0.008 between 9.64 and 11.71 nm). The dieters’ HDL2b levels decreased significantly when adjusted for their change in BMI (mean significance level, P = 0.04 for HDL protein between 10.07 and 11.31 nm). Similar results were also obtained when exercisers and dieters were adjusted to equivalent changes in percent body fat.

Associations with changes in weight, adiposity, calorie intake, and distance run

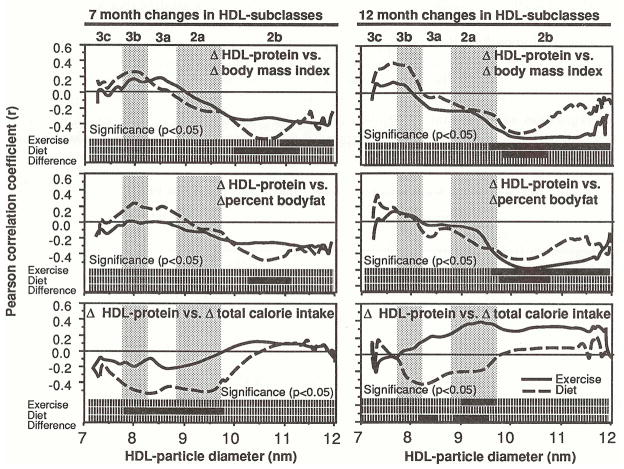

Figure 3 displays the correlations between changes in HDL-protein and BMI, percent body fat, and calorie intake in exercisers and dieters. The bars at the bottom of each graph designate the diameter values with correlations that are significantly different from zero. A third bar designates the diameter values where the exercisers’ correlation coefficient is significantly different from that of the dieters. Reductions in BMI correlated significantly with increases within HDL2b in exercisers after 7 months (11.03 to 11.92 nm) and 12 months (9.54 to 11.74 nm), and in dieters at 7 months (9.98 to 11.17 nm) and 12 months (9.80 to 10.65 nm). Reductions in percent body fat also correlated with increases within HDL2b in exercisers and in dieters. Changes in total calorie intake correlated negatively with the dieters’ HDL changes after 7 months (7.77 to 9.71 nm) and positively with the exercisers’ HDL changes after 12 months (9.07 to 9.60 nm diameter). The correlation of changes in calorie intake with changes in HDL protein within HDL3a and HDL2a was significantly different in exercisers and dieters (specifically between 8.24 and 9.57 nm). In exercisers, the correlations between changes in HDL-protein and distance run were not statistically significant.

Fig 3.

Correlation coefficients between changes in HDL-protein and changes in BMI, percent body fat, and caloric intake in 35 exercisers and 31 dieters. Coefficients are plotted at each diameter value. The bars at the bottom of each graph give the statistical significance. Solid bars designate significance (P=0.05), and broken bars designate nonsignificance. A third bar designates the diameter values where the exercisers’ correlation coefficient is significantly different from that of the dieters (solid).

Table 4 shows that weight-loss is associated with a shift of the predominant (highest) HDL peak from HDL3b to HDL3a. Specifically, when data from all three groups are combined, BMI decreased more after 1 year in men who changed from a predominant-3b peak to a predominant-3a peak (i.e., 3b → 3a transition) than it did in men who retained a predominant-3b peak (i.e., 3b → 3b transition). BMI also decreased significantly less in men who changed from a predominant-3a peak to a predominant-3b peak (i.e., 3a → 3b transition) than it did in men who retained a predominant-3a peak (i.e., 3a → 3a transition). The proportion of men who changed their predominant peak from HDL3b to HDL3a was not significantly different between exercisers (36% after 7 months, 22% after 1 year), dieters (33% after 7 months, 53% after 1 year), or controls (18% after 7 months, 24% after 1 year).

Table 4.

Mean changes in BMI in men who maintained and changed their predominant-HDL peak

| Sample Size | Changes in BMI (Mean±SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ 0 to 7mo | Δ 0 to 12mo | Δ 0 to 7mo | Δ 0 to 12mo | |

| Predominant-3b peak at baseline | ||||

| Changed (3b→3a) | 14 | 10 | −1.74 ± 0.32 | −2.69 ± 0.33 |

| No change (3b→3b) | 26 | 30 | −0.92 ± 0.27 | −0.74 ± 0.26 |

| Difference [(3b→3a) − (3a→3b)] | −0.83 ± 0.43 | −1.95 ± 0.41† | ||

| Predominant-3a peak at baseline | ||||

| Changed (3a→ 3b) | 16 | 20 | −0.63 ± 0.24 | −0.58 ± 0.24 |

| No change (3a→3a) | 41 | 37 | −1.25 ± 0.23 | −1.49 ± 0.27 |

| Difference [(3a→3b) − (3a→3a)] | 0.62 ± 0.33 | 0.91 ± 0.36* | ||

| Difference [(3b→3a) − (3a→3b)] | −1.21 ± 0.41* | −2.11 ± 0.41† | ||

NOTE. N = 97, all participants.

Significance levels for two-sample t test:

P < 0.0l,

P <0.000l.

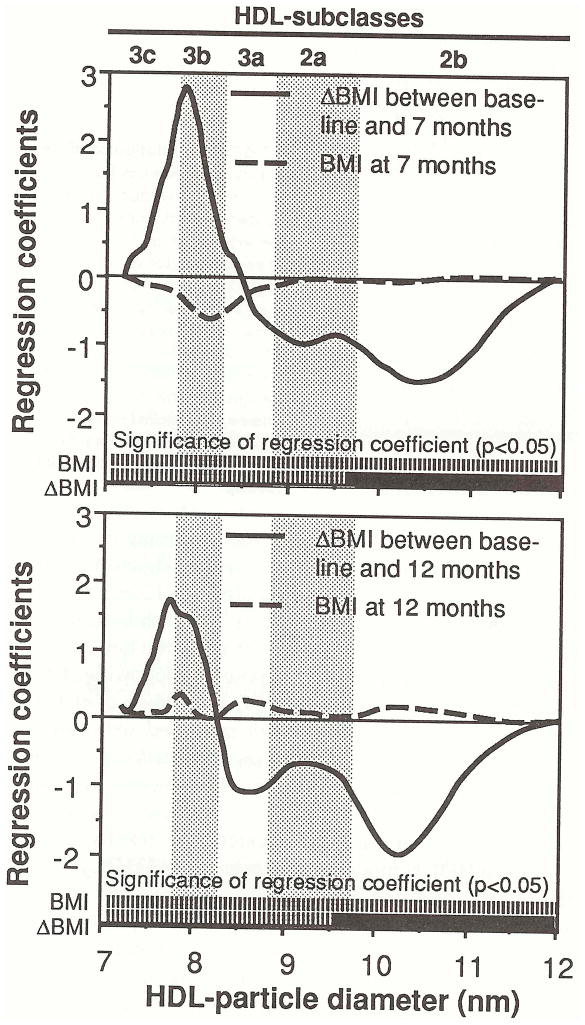

Regression analysis of weight-loss and post-treatment weight

Figure 4 shows that post-treatment HDL2b levels in 35 exercisers were more strongly related to the amount of weight-loss than to post-treatment weight. These are similar to the analyses presented in Table 3, i.e., the multiple regression analyses for determining whether the exercisers’ HDL-protein levels at 7 months and 12 months are better predicted by the post-treatment BMI or the change in BMI since starting to run. The regression coefficients are plotted for each diameter value, and their associated significance levels are given by the solid lines (P < .05) and broken lines (NS) at the bottom of the figures. The figure shows that the exercisers’ cross-sectional HDL2b levels at 7 months and 12 months were significantly related to the amount of weight lost since baseline, and not to the cross-sectional BMI measurements at 7 months and 12 months. At 7 months, cross-sectional HDL between 9.64 and 11.98 nm was related to the change in BMI from baseline (average significance level, P = 0.0l), but not to the cross-sectional BMI at 7 months (average significance level, P = .86). At 12 months, cross-sectional HDL between 9.60 and 11.72 nm was related to the change in BMI (average significance level, P = 0.03), but not to the cross-sectional BMI at 12 months (average significance level, P = 0.88). Similar results were obtained for regression analyses that used percent body fat as the dependent variable.

Fig 4.

Multiple regression analyses for testing whether post-treatment HDL levels in 35 exercisers were more strongly related to weight-loss since baseline or to posttreatment weight (BMI). For example, the top figure displays the α and β regression coefficients for the model HDL7 mo= intercept + α ΔBMI + βBMI7 mo, where ΔBMI is the change in BMI between baseline and 7 months, and BMI7 mo is the 7-month BMI measurement. The associated significance levels for the coefficients are given by the solid (P < 0.05) and broken bars (NS) at the bottom of the figure.

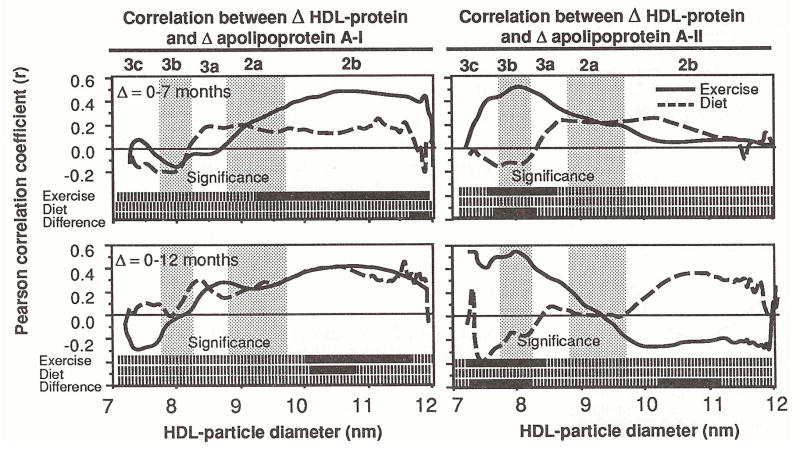

Relationships Between Changes in HDL Protein, Apo A-I, and Apo A-II

Figure 5 presents the correlations between changes in protein-stained HDL and changes in apo A-I and A-II in exercisers and dieters. As in Fig 2, significance levels are given at the bottom for whether the coefficients are different from zero, and for whether the exercisers’ and dieters’ coefficients are different from each other. Changes in exercisers’ apo A-II correlated positively with changes within HDL3c/3b at 7 months (7.51 to 8.32 nm) and at 12 months (7.52 to 8.42 nm). Changes in the dieters’ apo A-II correlated negatively with changes in HDL3b/3c, but not significantly. The correlations are significantly different between exercisers and dieters within the HDL3b/3c region at 7 months and 12 months (7.58 to 8.24 and 7.30 to 8.23 nm, respectively) and within the HDL2b region at 12 months (10.23 to 11.12 nm). Changes in the exercisers’ apo A-I correlated significantly with their changes within HDL2b at both 7 months (9.54 to 12.0 nm) and 12 months (10.00 to 11.23 nm); the correlations were not different from those of the dieters.

Fig 5.

Correlation coefficients between changes in HDL-protein and changes in apo A-I and A-II concentrations in exercisers and dieters. Coefficients are plotted at each diameter value. Two bars at the bottoms of the graphs give their statistical significance. Solid bars designate significance (P < 0.05), and broken bars designate nonsignificance. A third bar designates the diameter values where the exercisers’ correlation coefficient is significantly different from that of the dieters (solid).

DISCUSSION

Apo A-I and A-II

We have shown in this controlled randomized experiment that a 12-month exercise program significantly increased plasma apo A-I concentrations (Table 1). The increase appears to be due to the metabolic effects of weight-loss (see discussion below). When adjusted for weight-loss, the increase in apo A-I was significantly less in dieters than in exercisers (Table 1). Within the exercise group, changes in apo A-I correlated significantly with distance run, amount of weight lost, increased calorie intake, and improved fitness (Table 2). These results are consistent with cross-sectional studies that show that apo A-I is elevated in male long-distance runners [19–21]. Other approaches to studying apo A-I in exercisers have yielded less consistent results than cross-sectional studies. Studies on acute effects show that apo A-I may [22] or may not increase [23,24] after extended bouts of exercise. Some training studies show an increase in apo A-I [25], whereas others show no change [26–29]. Small sample size or short study duration may limit the statistical power of previous training studies to detect change, and most are uncontrolled. Although studies of diet-induced weight-loss usually show little or no change in apo A-I, their small sample size, uncontrolled design, and short duration make their negative findings difficult to interpret. Our findings support Schwartz’s finding that exercise-induced weight-loss increases apo A-I more than diet-induced weight-loss [8].

Gradient Gel Electrophoresis of Protein-Stained HDL

Cross-sectional studies show that runners have higher plasma concentrations of HDL2-cholesterol and HDL2-mass than sedentary men [19,30]. In the present study, we have previously reported that both exercise-induced and diet-induced weight-loss increase HDL2-cholesterol and HDL2-mass [1,2]. HDL2 includes two major subfractions: HDL2a and HDL2b. The analyses of Fig 2 show that the two weight-loss modalities increased the HDL2b subfraction without significantly altering HDL2a levels. Since HDL2a includes both apo A-I and apo A-II, whereas most particles within HDL2b contain apo A-I but not apo A-II, an increase in HDL2b should be associated with a predominant increase in apo A-I, without an increase in apo A-II concentrations, as was observed.

Previous exercise and diet studies have reported inconsistent changes in HDL3 cholesterol and HDL3-mass. Although both HDL3-cholesterol and HDL3-mass increased significantly in this trial [1,2], both are poor indicators of HDL3b-protein [6]. In the present study, HDL3b/3c decreased during diet-induced and exercise-induced weight-loss (Fig 2). An earlier cross-sectional study that used analytic ultracentrifuge measurements of HDL-mass showed that runners had less F1.20 0 to 1.5 mass than sedentary men [30]. HDL mass within this flotation range correlates most strongly with HDL3b/3c [6]. However, unlike the gradient gel, the F1.20 0 to 1.5 region appears as part of the HDL continuum in the analytic ultracentrifuge, rather than as a separate HDL3b component.

HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II)

The exercise and diet effects we observed are probably the compilation of separate changes within two overlapping HDL-particle distributions. The distributions have different apo compositions. The HDL particles that contain both apo A-I and apo A-II make up the HDL(A-I with A-II) particle distribution, and those that contain apo A-I but no apo A-II make up the HDL(A-I without A-II) particle distribution [31]. In normal men, the HDL(A-I with A-II) includes major components within the HDL3b, HDL3a, and HDL2a subclasses [32]. The HDL(A-I without A-II) particle distribution includes major components within the HDL3c, HDL3a, and HDL2b subclasses. Studies by Atmeh et al suggest that HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II) have minimal exchange of their apo A-I [33]. Metabolic interconversions between HDL subclasses appear to occur principally within the HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II) families of particles [32].

There are some indications that the HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II) particle distributions may have been affected differently by exercise and diet. Table 2 shows that changes in the exercisers’ BMI correlated positively with apo A-II and negatively with apo A-I. Changes in the exercisers’ treadmill test duration also had opposite effects on apo A-II (negative correlation) and apo A-I (positive correlation). Reductions in apo A-II could reflect reductions in HDL (A-I with A-II), of which the HDL3b reductions are only part. There were also significant differences in the correlations between changes in apo A-II with HDL-protein in dieters and exercisers (Fig 5). This could reflect different effects of diet-induced and exercise-induced weight-loss on HDL(A-I with A-II) within the HDL3a/2a region. These may not appear in the total HDL profile because this is where the overlap between HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II) is greatest; disparate changes in the concentrations of HDL(A-I with A-II) and HDL(A-I without A-II) particles could occur within the HDL3a/2a region with little alteration in total protein-stained HDL. We may be able to detect changes in HDL2b and HDL3b/3c because these components are positioned at the ends of the distribution, which may be more homogeneous than the middle of the distribution.

Weight-Loss and HDL

In this study, we attempted to reduce weight by two different methods: (1) increase exercise while holding calorie intake constant, and (2) reduce calorie intake while holding exercise constant. The HDL changes that occurred by each weight-loss method were compared with those of controls who neither exercised nor dieted. Changes in apo A-I and HDL2b correlated with weight-loss in the exercise group. We adjusted the HDL changes for the effects of weight-loss by analysis of covariance. This eliminated the exercisers’ increases in apo A-I and HDL2b, their decreases in HDL3b/3c, and the dieters’ decreases in HDL3b/3c. These HDL changes could therefore be due to metabolic processes associated with weight-loss (e.g., increased adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity [34,35], reduced plasma free fatty acid concentrations [36,37], and reduced hepatic lipase activity [37,38]). Adjustment for weight-loss accentuated the mean differences between the exercisers’ and dieters’ apo A-I and HDL2b responses. The effects of increased adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity, reduced plasma free fatty acid concentrations, and reduced hepatic lipase activity on HDL may be mitigated by the reduced calorie flux in dieters and accentuated by increased calorie flux in exercisers.

Table 3 shows that post-treatment apo A-I, HDL2-cholesterol concentrations, and HDL2-mass concentrations at 7 months and 12 months were more strongly related to the amount of weight lost since the beginning of the trial than to the post-treatment weight. Figure 4 shows that this is also true for HDL2b levels at 7 months and 12 months. This observation was initially made for HDL-cholesterol and HDL2-mass in an earlier study of 35 men who had run for 1 year, which led Williams to propose the following theory: Long-distance runners have the HDL metabolism of men who are below their usual weight (their purported sedentary setpoint weight) and not the metabolism of equivalently lean men who are neither exercising or dieting [10]. The analyses of Table 3 confirm the initial observation in a new independent sample. Table 3 and Fig 5 also extend the results to three additional HDL components: protein-stained HDL2b, HDL2-cholesterol, and apo A-I. The analyses suggest that the metabolic effects of weight-loss on HDL metabolism depend on a frame of reference within an individual, e.g., relative to a person’s usual weight (within-person relativity), rather than on a frame of reference between individuals, e.g., the absolute measurement of adiposity relative to other members of the population (between-person relativity) [11]. The importance of distinguishing between these two frames of reference has been shown to be critical in interpreting HDL-cholesterol levels in runners [10]. Most cross-sectional studies have concluded that differences in runners and sedentary men are not due to the runners’ leanness, because they assume between-person relativity in their analyses. In contrast, analysis of covariance (Fig 2) and other analyses based on within-person relativity [10,11] suggest that the elevated levels of HDL-cholesterol, HDL2b, and apo A-I concentrations of long-distance runners are primarily consequences of reduced adiposity.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by Grants No. HL-24462, HL-02183, HL-18574, and HL-30086 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, and conducted at the Stanford Center for Research in Disease Prevention and at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory (Department of Energy Grant No. DE-ACO3-76SF0098 to the University of California).

We wish to thank Dr Marcia Stefanick, Dr Richard Terry, Dr Darlene Dreon, Barbara Frey-Hewitt, Nancy Ellsworth, and Laura Holl for their help in completing the study.

References

- 1.Wood PD, Stefanick ML, Dreon D, et al. Changes in plasma lipids and lipoproteins in overweight men during weight loss through dieting as compared with exercise. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1173–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Vranizan KM, et al. Changes in lipoprotein subfractions during diet-induced and exercise-induced weight loss in moderately overweight men. Circulation. 1990;81:1293–1304. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiens B, Lithell H. Lipoprotein metabolism influenced by training-induced changes in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:558–564. doi: 10.1172/JCI113918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PT, Wood PD, Krauss RM, et al. Does weight loss cause the exercise-induced increase in high density lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 1983;47:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(83)90153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanche PJ, Gong EL, Forte TM, et al. Characterization of human high-density lipoproteins by gradient gel electrophoresis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;665:408–419. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(81)90253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Vranizan KM, et al. Associations of lipoproteins and apolipoproteins with gradient gel electrophoresis estimates of high-density lipoprotein subfractions in men and women. Arteriosclerosis. 1992;12:332–40. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.3.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sopko G, Leon AS, Jacobs DR, et al. The effects of exercise and weight loss on plasma lipids in young obese men. Metabolism. 1985;34:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(85)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz RS. The independent effects of dietary weight loss and aerobic training on high-density lipoproteins and apolipoprotein A-I concentrations in obese men. Metabolism. 1987;36:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikkill EA. Role of lipoprotein lipase in metabolic adaptation to exercise training. In: Borensztajn J, editor. Lipoprotein Lipase. Chicago, IL: Evener; 1987. pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams PT. Weight-set point and the high-density lipoprotein concentrations of long-distance runners. Metabolism. 1990;39:460–467. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90003-u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams PT. Weight set-point theory predicts HDL cholesterol levels in previously-obese long-distance runners. Int J Obes. 1990;14:421–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nutrition Coordinating Center. Reference Food Table, version 10. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Vranizan KM, et al. The effects of long-distance running and weight loss on plasma low-density lipoprotein subfraction concentrations in men. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:623–632. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2+ precipitation procedure for quantitation of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1379–1380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Quantitation of high density lipoprotein subclasses after separation by dextran sulfate and Mg2+ precipitation. Clin Chem. 1982;28:1574. (abstr) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheung MC, Albers JJ. The measurement of apolipoprotein A-I and A-II levels in men and women by immunoassay. J Clin Invest. 1977;60:43–50. doi: 10.1172/JCI108767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindgren FT, Jensen LC, Hatch FT. The isolation and quantitative analysis of lipoproteins. In: Nelson GJ, editor. Blood Lipids and Lipoproteins: Quantitation, Composition and Metabolism. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1972. pp. 181–274. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Nichols A, et al. Identifying the predominant peak diameter of high-density (HDL) and low-density (LDL) lipoproteins by electrophoresis. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:1131–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert PN, Bernier DN, Cullinane EM, et al. High-density lipoprotein metabolism in runners and sedentary men. JAMA. 1984;252:1034–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg A, Frey I, Keul J. Apolipoprotein profile in healthy males and its relation to maximum aerobic capacity (MAC) Clin Chim Acta. 1986;161:165–171. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(86)90210-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lehtonen A, Viikari J, Enholm C. The effect of exercise on high density (HDL) lipoprotein apoproteins. Acta Physiol Stand. 1979;106:487–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1979.tb06430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamon-Fava S, McNamara JR, Farber HW, et al. Acute changes in lipid, lipoprotein, apolipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein particle size after endurance triathlon. Metabolism. 1989;38:921–925. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(89)90243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuusi T, Kostiainen E, Vartiainen E, et al. Acute effects of marathon running on levels of serum lipoproteins and androgenic hormones in healthy men. Metabolism. 1984;33:527–531. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(84)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wirth A, Diehm C, Kohlmeier M, et al. Effects of prolonged exercise on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Metabolism. 1983;32:669–672. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(83)90122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwartz RS. Effects of exercise training on high-density lipoproteins and apolipoprotein A-I in old and young men. Metabolism. 1988;137:1128–1133. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson PD, Cullinane EM, Sady SP, et al. Modest changes in high-density lipoprotein concentration and metabolism with prolonged exercise training. Circulation. 1988;78:25–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urata H, Sasaki J, Tanabe Y, et al. Effects of mild aerobic exercise on serum lipids and apolipoproteins in patients with coronary artery disease. Jpn Heart J. 1987;28:27–34. doi: 10.1536/ihj.28.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas TR, Adeniran SB, Iltis PW, et al. Effects of interval and continuous running on HDL-cholesterol, apolipoproteins A-I and B and LCAT. Can J Appl Sport Sci. 1985;10:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stubbe I, Gustafson A, Nilsson-Ehle P, et al. In-hospital exercise therapy in patients with severe angina pectoris. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1983;64:396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams PT, Krauss RM, Wood PD, et al. Lipoprotein subfractions of runners and sedentary men. Metabolism. 1986;35:45–52. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung MC, Albers JJ. Characterization of lipoprotein particles isolated by immunoaffinity chromatography: Particles containing A-I and A-II and particles containing A-I but no A-II. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:12201–12209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nichols AV, Blanche PJ, Shore VG, et al. Conversion of apolipoprotein-specific high-density lipoprotein populations during incubation of human plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1001:325–337. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atmeh RF, Shephard J, Packard CJ. Subpopulations of apolipoprotein A-I in human high-density lipoproteins, and their metabolic properties and response to drug therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;751:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(83)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nikkila EA, Taskinen MR, Rehunen S, et al. Lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of runners: Relation to serum lipoproteins. Metabolism. 1978;27:1661–1671. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(78)90288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz RS, Brunzell JD. Increase of adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase activity with weight loss. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:1425–1430. doi: 10.1172/JCI110171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vihko V, Sarviharju J, Souminen H. Effects of endurance training on concentrations of individual plasma free fatty acids in young men at rest and after moderate bicycle ergometer exercise. Ann Med Exp Biol Fenniae. 1973;51:112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bray GA. Metabolic effects of corpulence. In: Howard IA, editor. Recent Advances in Obesity Research. London, England: Newman; 1975. pp. 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marniemi J, Peltonen P, Vuori I, et al. Lipoprotein lipase of human postheparin plasma and adipose tissue in relation to physical training. Acta Physiol Stand. 1980;110:131–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1980.tb06642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]