Abstract

Furin belongs to the family of proprotein convertases (PCs) and is involved in numerous normal physiological and pathogenic processes, such as viral propagation, bacterial toxin activation, cancer and metastasis. Furin and related furin-like PCs cleave their substrates at characteristic multibasic consensus sequences, preferentially after an arginine residue. By incorporation of decarboxylated arginine mimetics in P1 position of substrate analogue peptidic inhibitors we could identify highly potent furin inhibitors. The most potent compound, phenylacetyl-Arg-Val-Arg-4-amidinobenzylamide (15), inhibits furin with a Ki-value of 0.81 nM and has also comparable affinity to other PCs like PC1/3, PACE4, and PC5/6, whereas PC2 and PC7 or trypsin-like serine proteases were poorly affected. In fowl plague virus (influenza A, H7N1)-infected MDCK cells inhibitor 15 reduced proteolytic hemagglutinin cleavage and was able to reduce virus propagation in a long term infection test. Molecular modelling revealed several key interactions of the 4-amidinobenzylamide residue in the S1 pocket of furin contributing to the excellent affinity of these inhibitors.

Introduction

Furin belongs to the proprotein convertases (PCs), a family of Ca2+-dependent multidomain mammalian endoproteases that contain a catalytic serine protease domain of the subtilisin type.1 Together with six other members of this family, PC2, PC1/3, PACE4, PC4, PC5/6, and PC7, furin possesses a strong preference for substrates containing the multibasic cleavage motif Arg-X-Arg/Lys-Arg↓-X.2-4

Furin and its analogues are responsible for the maturation of a huge number of inactive protein precursors5, 6 and are therefore involved in many normal physiological processes. However, several studies have also revealed a function of these proteases in numerous diseases, such as viral and bacterial infections, tumorigenesis, neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes and atherosclerosis.3, 4 For instance, furin-like PCs can process the HIV-1 surface protein gp160 into gp120 and gp41, which form an envelope complex necessary for the virulence of HIV-1.7 Additional potential substrates are surface proteins of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses of the H5 and H7 subtypes, from the hemorrhagic Ebola and Marburg viruses or from the measles virus that all must be cleaved at multibasic consensus sites to form their mature and fusogenic envelope glycoproteins.8-11 Furin is also involved in the pathogenicity of Bacillus anthracis because of its ability to activate the protective antigen precursor, one component of anthrax toxin.12 Early endosomal furin also activates several other bacterial toxins, such as Pseudomonas exotoxin, Shiga-like toxin-1, and diphtheria toxins.4 Upregulation of PCs was observed in many tumors and in some cases elevated PC expression could be correlated with enhanced malignancy and invasiveness, probably via activation of metalloproteases, angiogenic factors, growth factors and their receptors.13-16 However, the function of PCs in the regulation of tumor growth and progression seems to be more complex, because other reports describe that PCs are also involved in the activation of proteins with tumor suppressor functions, such as cadherins.17 PCs are involved in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer's disease by activation of α-, β- and γ-secretases or via the release of amyloidogenic peptides.18 The intracellular endoproteolytic PC-catalyzed activation of membrane-bound MT1-MMP in macrophages is important for plaque stability in atherosclerosis.19 The cleavage efficacy of the PCs towards a large number of potential substrates, some of which are likely to be involved in additional diseases, has been recently investigated in detail.5 Therefore, PC inhibitors might represent potential drugs for the treatment of these diseases.

Compared to other arginine-specific proteases, such as the trypsin-like serine proteases thrombin or factor Xa, only moderate progress has been achieved in the field of PC inhibitors. PCs are inhibited by various naturally occurring macromolecular protein-based inhibitors, additional bioengineered inhibitors have been designed by incorporation of the PC's consensus sequence into variants of the serpin α1-antitrypsin, the leech-derived eglin C, and of the third domain of turkey ovomucoid.20, 21 Most of the small molecule PC inhibitors belong to three groups, pure peptides, peptide mimetics or nonpeptidic compounds. Peptides derived from the PC prodomains22 or identified from a combinatorial library inhibit furin and some related PCs in the micromolar range.23 Improved activity was obtained by polyarginine24 or poly-d-arginine derived analogues, the most potent compound nona-d-arginine inhibits furin with a Ki value of 1.3 nM.25 The first potent peptidomimetic furin inhibitors were developed by coupling of appropriate multibasic substrate sequences to a P1 arginyl chloromethyl ketone group. The irreversible inhibitor decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK has now been used by many groups as reference to study the effects of furin and related PCs.9 Other groups developed ketone-based transition state analogues, which most-likely inhibit furin via formation of a reversible hemiketal.26 Although these ketone-derived inhibitors are valuable biochemical tools, especially for X-ray analysis27 and for preliminary in vivo studies – for example with fowl plaque virus8 – they are less suited for drug design. Ketones are often prone to racemization at the P1 Cα-carbon and can be attacked by numerous nucleophiles, which limits their stability in vivo.28 A boroarginine derived transition state inhibitor was used for the determination of the crystal structure of Kex2, a furin analogue protease from yeast.29

Excellent potency was described for a series of non-peptidic multibasic 2,5-dideoxystreptamine derivatives, which inhibit furin with Ki values < 10 nM and are highly selective towards trypsin-like serine proteases.30 Very recently, several non-peptidic inhibitors with micromolar affinities were identified by high-throughput screening.31

In the last years numerous groups have developed substrate analogue inhibitors for trypsin-like serine proteases containing decarboxylated P1 arginine mimetics, e.g., for the clotting proteases thrombin32, 33 and factor Xa.34 Such analogues are not susceptible towards degradation by carboxypeptidases and do not contain a negatively charged P1 carboxylate group, which should repel the inhibitor from the serine nucleophile in the enzyme's active site. Therefore, we incorporated some of these P1 residues in tetrapeptide derivatives derived from furin's consensus sequence and could identify the 4-amidinobenzylamide group as an excellent arginine replacement. Herein, we report the activity of these compounds on furin inhibition; for selected compounds we also describe their specificity towards the PC family and certain trypsin-like serine proteases. A model in complex with furin reveals several interactions of the P1 group which might contribute to the excellent potency of these compounds. One inhibitor was used to inhibit the replication of a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAIV) of subtype H7 in a cellular assay.

Results

Chemistry

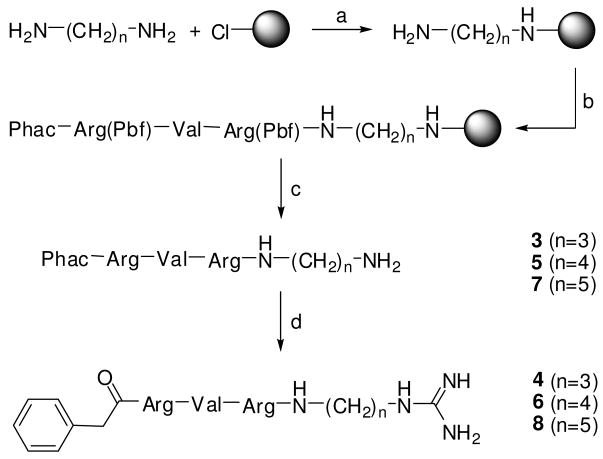

A combined solution and solid phase approach was used for inhibitor synthesis. All compounds containing a symmetric P1 diamine moiety as well as their guanylated analogues (3-12) were prepared on tritylchloride resin by standard Fmoc SPPS. Initially the resin was loaded with the diamine, followed by coupling of the P2 to P5 residues. The peptides were cleaved from resin to yield the unprotected amines. These were finally modified by treatment with 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine35 in a mixture of a Na2CO3-solution with DMF (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of inhibitors 3-8.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Tritylchloride resin, 2 equiv diamine, dry THF, 2 h; (b) Fmoc SPPS, double couplings with 4 equiv amino acid (or phenylacetic acid), HOBt and HBTU, respectively and 8 equiv DIPEA; (c) TFA/TIS/H2O (95/2.5/2.5, v/v/v), 2 h; (d) 3 equiv 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine · HCl, 4 equiv DIPEA in DMF/1 M Na2CO3 solution (1/1, v/v), 16 h.

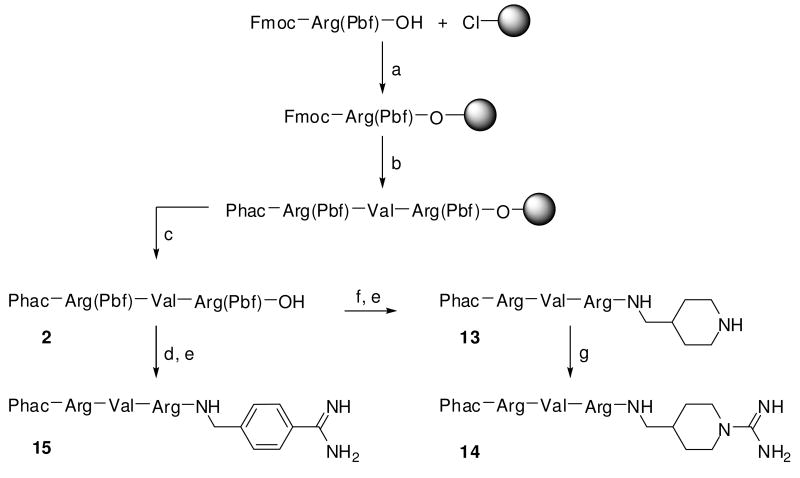

The P5-P2-segments of inhibitors 13-18 were prepared by standard Fmoc SPPS on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin (Scheme 2). After liberation of the side chain protected intermediate 2 from resin, 4-amidinobenzylamine · 2 HCl (1) was coupled in solution using PyBOP/DIPEA in presence of excess Cl-HOBt. Final side chain deprotection provided inhibitor 15. In analogy, 1-Boc-4-(aminomethyl)piperidine was coupled to fragment 2, followed by cleavage of protecting groups to yield 13, which was converted by treatment with 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine and DIPEA to inhibitor 14. The synthesis of compounds 16-18 was performed in analogy to inhibitor 15, using decanoic or acetic acid in the final coupling step.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of inhibitors 13–15.

Reagents and conditions: (a) Loading of 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, 4 equiv DIPEA, dry DCM, 2h; (b) Fmoc SPPS, conditions see scheme 1; (c) 1 % TFA in DCM, 2 × 30 min; (d) 1, 1.1 equiv PyBOP, 3 equiv 6-Cl-HOBt, 3 equiv DIPEA in DMF, 2 h; (e) TFA/TIS/H2O (95/2.5/2.5, v/v/v), 2 h; (f) 1-Boc-4-(aminomethyl)piperidine, 1.1 equiv PyBOP, 3 equiv 6-Cl-HOBt, 3 equiv DIPEA in DMF, 2 h; (g) 3 equiv 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine · HCl, 4 equiv DIPEA in DMF, 16 h.

Determination of inhibition constants

Our initial work was focused on the identification of a more drug-like P1 residue to replace the arginine ketone moieties used in previously described furin inhibitors. The peptide sequence of the inhibitors was derived from the chloromethyl ketone decanoyl-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK,7 whereas the P2 residue was changed to arginine to avoid a second guanylation of an unprotected Lys side chain during reactions with 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine, which would lead to homoarginine derivatives. In addition, the N-terminal decanoyl group was substituted by a hydrophobic phenyl acetyl group to facilitate UV detection, especially when intermediates without aromatic systems were to be analyzed on HPLC, e.g., analogues with aliphatic diamines in P1 position. The structures of the inhibitors synthesized are summarized in table 1.

Table 1.

Inhibition of furin by inhibitors of the general formula R-Arg-Val-P2-P1.

| Inhibitor | R | P2 | P1 | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

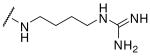

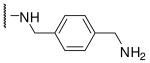

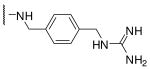

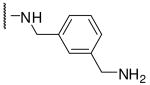

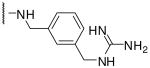

| 3 | Phac | Arg |  |

3020 |

| 4 | Phac | Arg |  |

63 |

| 5 | Phac | Arg | 7490 | |

| 6 | Phac | Arg |  |

78 |

| 7 | Phac | Arg | 553 | |

| 8 | Phac | Arg | 1070 | |

| 9 | Phac | Arg |  |

627 |

| 10 | Phac | Arg |  |

1430 |

| 11 | Phac | Arg |  |

1320 |

| 12 | Phac | Arg |  |

2730 |

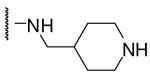

| 13 | Phac | Arg |  |

9710 |

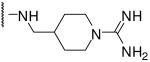

| 14 | Phac | Arg |  |

53 |

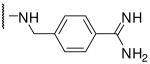

| 15 | Phac | Arg |  |

0.81 |

| 16 | Dec | Arg |  |

1.6 |

| 17 | Ac | Arg |  |

1.0 |

| 18# | Dec | Lys |  |

3.3 |

This compound was synthesized according to scheme 2 using Fmoc-Lys(Cbz)-OH for coupling of the P2 amino acid. The Cbz-group was removed in the final step by hydrogenation in 90 % acetic acid at room temperature overnight using Pd/C as catalyst.

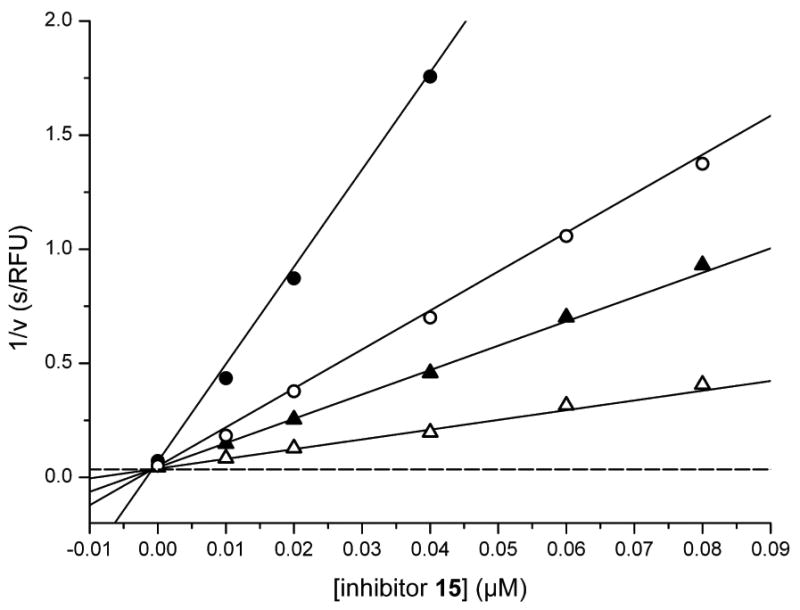

Initially we incorporated an agmatine moiety in P1 position, which directly corresponds to a decarboxylated arginine. Similar as described for substrate analogue thrombin inhibitors we prepared also the shorter and longer analogues36 and purified their corresponding amines (e.g., 5), which were obtained as intermediates directly after cleavage from resin. A similar inhibitory potency towards furin was observed for the agmatine (6) and noragmatine (4) derivatives, whereas their analogue amines are significantly less potent and have Ki values > 1 μM. In contrast, for the longer diaminopentane inhibitor 7 a slightly stronger potency compared to its guanylated analogue 8 was found. A poor potency was observed for both diaminoxylene inhibitors and their guanylated analogues (9-12), whereas the N-(amidino)piperidine-derived inhibitor 14 binds to furin with a Ki value of 53 nM. In preliminary investigations we could find only a poor inhibition of furin with simple benzamidine and 4-aminomethylbenzamidine (1) with inhibition constants of 0.75 and 1.2 mM, respectively. Therefore, we were delighted to observe excellent potency with the 4-amidinobenzylamide compound 15. Enzyme kinetic studies revealed that all compounds summarized in Table 1 act as reversible competitive inhibitors, as an example the Dixon-plot for inhibitor 15 is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dixon plot of inhibitor 15. Kinetic measurements were performed with four different substrate concentrations (pyroGlu-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC: ● 5, ○ 12.5, ▲ 20, and △ 50 μM) in presence of 0.95 nM furin using various inhibitor concentrations ≥ 10 nM. The dashed line represents 1/Vmax, which was obtained from a Michaelis-Menten curve measured at the same time in parallel on the same 96-well plate (Km = 4.9 μM, Vmax = 28.4 RFU/s).

For comparison to the reference inhibitor Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK we also prepared analogues with N-terminal decanoyl and acetyl groups and a P2-Lys-derivative. Whereas slightly reduced potency was observed for the decanoyl compound 16, an excellent Ki value was found for the acetylated inhibitor 17. The P2 Lys-inhibitor 18 has comparable activity compared to its Arg analogue 16 which indicates that both residues are well accepted by furin's S2 pocket.

Although some differences in substrate specificity exist between furin-like PCs,5 they all share a strong preference for similar multibasic cleavage sequences. Therefore, we assumed that these substrate analogue inhibitors also have the potential to inhibit other PCs. To prove this hypothesis, we selected five compounds and measured their selectivity towards related PCs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Specificity of selected inhibitors towards furin-like PCs and trypsin-like serine proteases (n.d., not determined).

| Ki (nM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitor | |||||||||

| furin | hPACE4 | hPC5/6 | hPC7 | hPC1/3 | hPC2 | thrombin | fXa | plasmin | |

| 6 | 78 | 42 | 85 | >10000 | 53 | > 10000 | 102000 | 83000 | 97000 |

| 14 | 53 | 67 | 173 | >10000 | 70 | > 10000 | 50000 | 123000 | >1000000 |

| 15 | 0.81 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 6154 | 0.75 | 312 | 23000 | 40000 | 6000 |

| 16 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 6.3 | 968 | 3.65 | 55 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| 17 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 3.6 | 5131 | 1.7 | 1388 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

As expected, also other PCs, such as hPACE4, hPC5/6, hPC2 were inhibited in a similar range by the selected inhibitors, whereas hPC7 and hPC2 were less affected. Surprisingly, the highest potency for hPC2 was observed with the decanoyl analogue 16. To further analyse selectivity three inhibitors with different P1 residues were also tested towards the trypsin-like serine proteases thrombin, factor Xa and plasmin, however, only a marginal inhibition of these proteases was found.

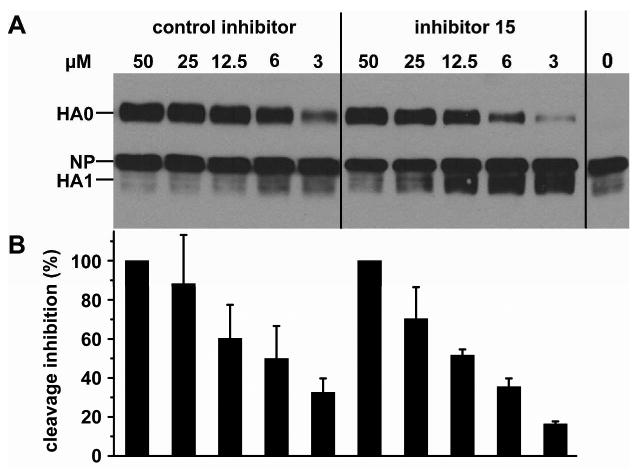

Inhibition of proteolytic hemagglutinin (HA) cleavage of fowl plague virus (FPV)

The virus surface HA-spike protein of FPV, which belongs to the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses of the subtypes H5 and H7, is synthesized as precursor molecule HA0. HA0 is cleaved by furin or by a furin-like protease, present in all cells, at a multibasic cleavage site into the distal subunit HA1 and the membrane-anchored subunit HA2. The cleavage occurs during the HA transport from the ER to the plasma membrane, where virus assembly and budding takes place.37, 38 At the beginning of infection, after receptor-binding and endocytosis, the viral envelope merges with endosomal membrane. The viral genome and accessory proteins are delivered into the cell nucleus, where multiplication of influenza virus progeny proceeds. The fusion step is essential for each host cell infection cycle and is absolutely dependent on correctly cleaved HA. However, it should be mentioned that cleavage is not required for hemagglutination and for virus assembly. We selected inhibitor 15 to study its effects on the proteolytic processing of HA0 in FPV infected cells (Figure 2). FPV-infected cell cultures were exposed to different concentrations of inhibitor 15 and Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK, which was used as control. When viruses in the cell supernatant reached a hemagglutination titer of 27 HAU, cell lysates were prepared and viral proteins analyzed. Cleavage of HA is most reduced with both inhibitors at a concentration of 50 μM (Figure 2A). Stepwise two-fold dilution of the inhibitors is associated with a gradual loss of non-cleaved HA0, which was quantified by using a near-IR dye-labelled antibody. The IC50 value of compound 15 is approximately 10 μM and is in a similar range to that found for the control inhibitor (Figure 2B). Very similar results in this cellular assay were also obtained with the decanoyl inhibitor 16, whereas the acetyl analogue 17 had reduced activity (data not shown). At 50 μM concentrations of the inhibitor 15 the virus particles obtained from inhibitor-treated cells contain considerable (> 80%) non-cleaved HA (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of fowl plague virus hemagglutinin cleavage by compound 15 and Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK as control. (A) Confluent MDCK cell cultures were infected with egg-grown influenza virus A/FPV/Rostock/34 (H7N1) at a MOI of 10 per cell. Inhibition of HA cleavage (PSKKRKKR↓GLFG) at different inhibitor concentrations was analyzed after cell lysis 16 h post infection. Proteins from virus-infected cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. Viral proteins were immunochemically detected by using rabbit anti-FPV serum and ECL reaction kit (Pierce): HA0 (82 kDa), nucleoprotein NP (56 kDa) and HA1 (∼50 kDa), whereas HA2 (32 kDa) was not detectable by the antiserum used. (B) Quantification of HA cleavage inhibition. Three independent experiments for both inhibitors were performed using a modified Western blot analysis technique allowing quantification by a near-IR dye-labelled second monoclonal antibody applicable for the LI-COR Odyssey Image-System. The maximum amount of HA0 obtained by inhibition with 50 μM Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK was normalized to 100 % cleavage inhibition. Other HA0 band intensities at different concentrations were measured and equalized by standardization of each HA0 value correlating with the corresponding nucleoprotein NP band (56 kDa).

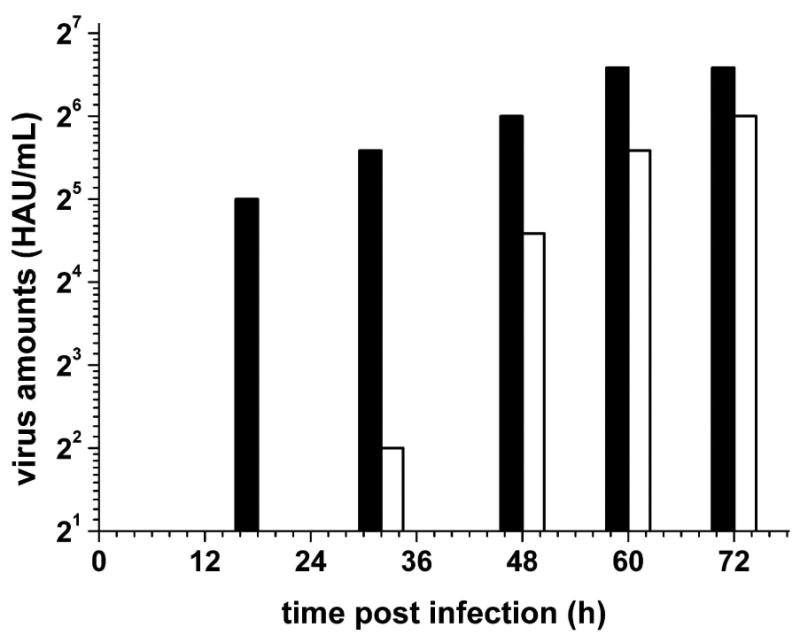

Multiple cycle replications of FPV in the presence and absence of inhibitors

Inhibitory effects on long-term virus infection were examined by multiple cycle replication of FPV after an inoculation of the cell cultures with low multiplicity of infection (MOI). This type of experiment results in a retardation and reduced virus replication in the presence of inhibitors.39 MDCK cells were infected by FPV at a low MOI of 10-5 and incubated in the presence of 25 μM compound 15 and in the absence of any inhibitor for up to 72 h. The FPV propagation in presence of compound 15 at 25 μM was monitored by virus titration of released virus into the cell culture supernatants using the standard hemagglutination test39 (Figure 3). Virus release appears delayed by about 24 h in comparison to FPV-infected cell cultures which were not treated with inhibitor and in which FPV has more rapidly proliferated. The fact that FPV is still produced after a period of delay up to nearly the same level as obtained without inhibitor demonstrates that the viability of the cells is not noticeably influenced in the presence of inhibitor.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of multiple cycle replication of FPV in cell culture in the absence (filled bars) and in the presence of inhibitor 15 (white bars). Cultures of MDCK cells were inoculated with the Rostock strain of FPV at an MOI of 10-5 PFU per cell and incubated in DMEM without FCS at 37°C. The inhibitor was added to the medium reaching a final concentration of 25 μM. At different times (10, 18, 32, 48, 60, and 72 h p.i.) the virus amount released into the medium was measured by hemagglutination titration (HAU), at 10 h no released viruses was detected in both groups. Mean values of four independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

A search for suitable replacements of the P1 arginylketones in a series of peptidic furin inhibitors revealed various alternatives among decarboxylated arginine mimetics, known from previous developments of trypsin-like serine protease inhibitors. The incorporation of 4-amidinobenzylamide, originally used for the development of the thrombin inhibitor melagatran and of its hydroxyamidino prodrug ximelagatran,32 of noragmatine,40 agmatine36 and 4-amidomethyl-N(amidino)piperidine41, provided potent inhibitors of furin and related PCs, such as hPACE4, hPC5/6, and hPC2. The limited selectivity towards the PC family might be a drawback of these inhibitors under some circumstances, but otherwise could provide some advantage for special applications, ie if PCs are coexpressed in cells and the inhibition of only one PC may not be sufficient. The low affinity of the selected inhibitors towards thrombin, factor Xa and plasmin, which is in the range of simple benzamidines, should be advantageous for maintaining the homeostasis of blood without affecting the well-balanced clotting and fibrinolysis systems. One of the reasons for the different affinities towards PCs and trypsin-like proteases is most likely the different requirements for the configuration of the P3 residue. Most of the potent non-covalent substrate analogue trypsin-like serine protease inhibitors contain a P3 residue in the d-configuration, whereas the herein-described PC inhibitors possess a L-amino acid at this position.

Very often peptidic structures suffer from poor stability due to rapid proteolysis. However, due to the missing C-terminal carboxyl group we assume that the inhibitors described in Table 1 are resistant towards cleavage by carboxypeptidases, whereas the N-terminal acetylation should stabilize them against aminopeptidases. However, at present we have no information regarding the stability of these compounds towards endoproteases.

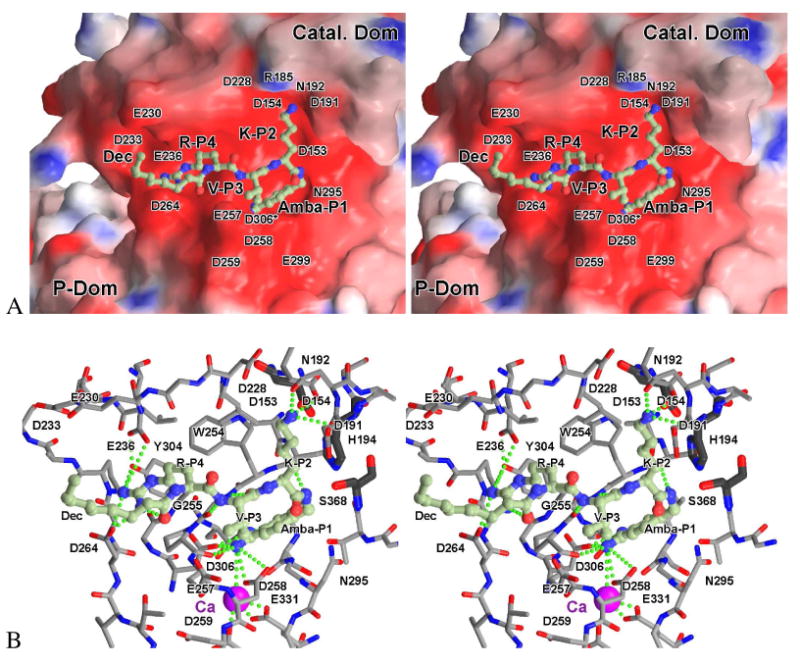

To get a first idea regarding the binding mode of the 4-amidinobenzylamide in the S1 pocket we modeled the complex of inhibitor 18 bound to furin, based on the known X-ray structure of mouse furin in complex with the irreversible inhibitor Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Arg-CMK.27 Therefore, we replaced the arginyl-chloromethyl ketone group in the 1p8j-complex by 4-amidinobenzylamide followed by energy minimization. As only three amino acid residues vary between the catalytic domains of the mouse and the human enzymes, none being in proximity to the catalytic cleft, the modeled complex between inhibitor 18 and the mouse-enzyme should also be representative of the human enzyme (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Stereoview of the modeled complex between inhibitor 18 (Dec-Arg-Val-Lys-Amba) and mouse furin. A) The inhibitor (ball-and-stick model) is shown in front of the solid surface of the catalytic domain, colored according to its calculated negative (-15 e/kT, red) and positive (15 e/kT, blue) electrostatic potential. Most of the amino acids responsible for the strong negative surface potential in the vicinity of the active site are labelled. Asp306 (denoted by an asterisk) is actually located below the enzyme surface at the bottom of the S1-pocket, making a direct contact with the amidino-moiety of the inhibitor (see also panel B). B) Stick model of the surrounding residues together with the inhibitor (ball-and-stick model, carbon in light green). Furin carbons are colored grey, oxygens red and nitrogens blue. The catalytic residues are shown as thicker dark-grey sticks, and the calcium 2 ion at the bottom of the S1-pocket as a purple sphere. For clarity water molecules were omitted and only important enzyme residues involved in interactions to the inhibitor and/or being responsible for the strong negative surface potential are labelled. Strong H-bond and salt bridge contacts discussed in the text are indicated by dotted green lines. Panel B was slightly rotated with respect to panel A to improve the visibility. A pdb file of the modelled complex is available as supporting information.

Based on the modelled structure we could identify several interactions between the P1 residue and furin which may explain the high potency of the 4-amidinobenyzlamide inhibitors. The amidino group binds to the carbonyl oxygen of Ala292 and makes salt bridges to the carboxyl side chains of Asp306, and Asp258. In addition, a weak hydrogen bond is formed between the carbonyl oxygen of Pro256 and the surrounding water molecules, connecting the amidinobenzyl-moiety via the Ca2+-ion to the carboxyl side chains of Glu331 and Asp301. The benzyl ring is sandwiched between the main chains of Trp254-Gly255 and Gly294-Asn295, similar to the guanidino group of the P1 Arg seen in the experimental structure. Several other hydrogen bonds are formed between the enzyme and the inhibitor, which are identical to the X-ray structure. The P2 Lys amino group binds to the carboxyl residue of Asp154, the side chain amide of Asn192, and weakly to the carbonyl of Asp191. In addition, hydrogen bonds are formed to a cluster of water molecules. A P2 Arg side chain should easily be accommodated by a slight rearrangement of those water molecules and – again after a slight structural rearrangement – potentially by additional interaction(s) with the carboxyl side chains of Asp228 and Asp191. The backbone of the P3 Val forms a short antiparallel β-sheet to Gly255, reminiscent of similar interactions between the d-P3-residue in trypsin-like serine protease inhibitors with the protease residue Gly216. However, in case of substrate analogue furin inhibitors an l-configuration of the P3 residue is required, because the space above the indole ring of Trp254 is filled by the side chain of Leu227 and is therefore not accessible for the side chain of a P3 amino acid in the d-configuration. The above mentioned β-sheet is completed by a hydrogen bond between the P1-amide NH and the carbonyl of Ser253. The NH and carbonyl oxygen of the P4 Arg and the decanoyl carbonyl group are involved in hydrogen bonds with surrounding water molecules, bridging interaction with the amide NH of Glu257. The P4 guanidine group makes salt bridges to Asp264 and Glu236. It forms further tight hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl oxygen of its own P5 residue and the OH of Tyr308, connecting it again with the carboxyl side chain of Glu236.

These newly described inhibitors should be useful tools for further studies of the physiological role of furin-like PCs. In a first application compound 15 inhibited the multiple cycle replication of FPV in cell culture and suppressed the activation of the HA precursor HA0 in FPV infected cells with similar potency as observed for the chloromethyl ketone-based control inhibitor. However, in contrast to the nanomolar Ki-values a significantly higher inhibitor concentration of approximately 10 μM was required in the cellular assay to obtain a 50% inhibition of HA0 cleavage. The reduced potency could be related to the predominant intracellular localization of furin within the trans-Golgi network,42 which makes the protease poorly accessible to such multibasic and polar inhibitors. A strong discrepancy between potent in vitro activity and significantly reduced efficacy in cellular assays was found also for many other furin inhibitors.25, 30, 43-45 In contrast, relatively low differences were determined for a recently discovered series of more hydrophobic dicoumarols, the obtained IC50-values from cellular assays were only slightly increased compared to their Ki-values, which were in the range between 1 and 20 μM.31

Despite equipotent activity between inhibitor 15 and the chloromethyl ketone inhibitor we believe that the 4-amidinobenzylamide derivatives have a significant advantage due to their improved stability. We could not detect any change in the elution profile of inhibitor 15 by HPLC, when a stock solution of the inhibitor was stored in water at room temperature over a period of two weeks. The synthesis and incorporation of the chemically stable 4-amidinobenzylamide group into peptidic inhibitors is less laborious than the preparation of arginyl ketone derivatives. Therefore, a more simple optimization of these PC inhibitors will be possible in future. Our work is presently focused on the design of inhibitors with different selectivity profiles and improved physicochemical properties, including the use of well known benzamidine prodrug strategies, to enhance cell permeability and bioavailability. We assume that these are important prerequisites to further enhance the activity of the 4-amidinobenzylamide-derived furin inhibitors in cellular assays and to identify suitable candidates for evaluation in animal models.

Experimental section

Analytical HPLC experiments were performed on a Shimadzu LC-10A system (column: Nucleodur C18, 5 μm, 100 Å, 4.6 × 250 mm, Machery-Nagel, Düren, Germany) with a linear gradient of acetonitrile (1-70 % in 69 min, detection at 220 nm) containing 0.1 % TFA at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The final inhibitors were purified to more than 95 % purity (detection at 220 nm) by preparative HPLC (pumps: Varian PrepStar Model 218 gradient system, detector: ProStar Model 320, fraction collector: Varian Model 701) using a C8 column (Nucleodur, 5 μm, 100 Å, 32 × 250 mm, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) and a linear gradient of acetonitrile containing 0.1 % TFA at a flow rate of 20 mL/min. All inhibitors were finally obtained as TFA-salts after lyophilization. The molecular mass of the synthesized compounds was determined using a QTrap 2000 ESI spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). The NMR 1H- and 13C-spectra were recorded on a ECX-400 (Jeol Inc., USA) at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively and are referenced to internal solvent signals.

Reagents for synthesis: Fmoc amino acids, coupling reagents and reagents for synthesis were obtained from Orpegen, Novabiochem, Iris, Fluka, Aldrich or Acros. The automated solid phase peptide synthesis was performed in a Syro 2000 (MultiSynTech GmbH, Witten, Germany).

4-amidinobenzylamine · 2 HCl (1)

10 g (32 mmol) Boc-4-acetylhydroxyamidinobenzylamide34 was solved in 500 mL 90 % acetic acid and treated with 650 mg catalyst (10 % Pd/C) under an atmosphere of hydrogen. The mixture was hydrogenated over a period of 48 h, the catalyst was removed by filtration and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The remaining Boc-4-amidinobenzylamide · acetate was dissolved in 150 mL water and treated with 40 mL concentrated HCl. After stirring for 1.5 h at RT the solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was lyophilized from water (white solid; yield: 6.8 g, 30.6 mmol; MS calc.: 149.09, found 150.0, (M+H)+; 1H-NMR (400 MHz, D2O): δ [ppm] = 4,46 (s, 2 H), 7,80-8,01 (2d, 4 H, aromatic); 13C-NMR (100 Mhz, D2O): δ [ppm] = 42.64 (CH2), 128.65, 129.26, 129.62, 138.69 (aromatic), 166.47 (carbon amidino group)).

Phac-Arg(Pbf)-Val-Arg(Pbf)-OH (2)

Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH (1.509 g, 2.325 mmol, 1 equiv) was dissolved in 15 mL dry DCM and 1.548 mL (9.3 mmol, 4 equiv) DIPEA, which was immediately poured onto 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin (1.5 g, 1 equiv, resin loading: 1.55 mmol/g). The mixture was shaken for 2 h at RT followed by treatment with DCM/MeOH/DIPEA (17/2/1, v/v/v, 3 × 1 min), washed several times with DCM, DMF, DCM and dried in vacuo. The synthesis proceeded by manual Fmoc SPPS using a 4-fold excess of Fmoc-amino acid, HOBt and HBTU, respectively and 8 equiv DIPEA. The phenylacetic acid was coupled in accordance to the amino acids. The protected peptide was cleaved from resin by 1 % TFA in DCM (2 × 30 min) at RT. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the peptide lyophilized from 80 % tert-BuOH in water (white solid; yield 1.452 g, 1.38 mmol; purity > 97 % based on HPLC at 220 nm; retention time 64.6 min; MS calc.: 1051.49, found 1052.5 (M+H)+).

Phac-Arg-Val-Arg-3-(amido)propylamine · 3 TFA (3)

1,3-diaminopropane (50.03 μL, 0.6 mmol, 4 equiv) was dissolved in 1.2 mL dry THF and poured immediately onto tritylchloride resin (0.1 g, resin loading: 1.5 mmol/g). The mixture was shaken for 2 h at RT, followed by treatment with DCM/MeOH/DIPEA (17/2/1, v/v/v, 3 × 1 min) and was washed several times with DCM, DMF and DCM. The synthesis proceeded by automated Fmoc SPPS as described for the manual synthesis of compound 2. The product was cleaved by shaking the resin in TFA/TIS/H2O (95/2.5/2.5, v/v/v) for 2 h at RT, followed by filtration and precipitation with cold ether. The precipitate was washed two times with ether and dried. The product was purified by preparative HPLC and lyophilized from 80 % tert-BuOH in water (white solid; yield: 39 mg, 0.041 mmol; retention time: 22.2 min; MS calc.: 603.4, found 604.6 (M+H)+).

The synthesis of inhibitors 5, 7, 9 and 11 was performed in identical manner; for analytical data see supporting information.

Phac-Arg-Val-Arg-3-(amido)propylguanidine · 3 TFA (4)

To obtain compound 4, the corresponding amine was prepared in accordance to compound 3. The precipitated amine was solved in a mixture of 1 mL 1 M Na2CO3-solution/DMF (1/1, v/v) followed by addition of 1H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine · HCl (68.1 mg, 0.45 mmol) and DIPEA (106 μL, 0.6 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 16 h at RT and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by preparative HPLC and lyophilized from 80 % tert-BuOH in water (white solid; yield: 40 mg, 0.041 mmol; retention time: 23.4 min; MS calc.: 645.4, found 646.5 (M+H)+).

The synthesis of inhibitors 6, 8, 10 and 12 was performed by an identical procedure; for analytical data see supporting information.

Phac-Arg-Val-Arg-4-(amidomethyl)piperidine · 3 TFA (13)

Compound 2 (105.2 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1 equiv), 1-Boc-4-(aminomethyl)piperidine (Fluka, 21.43 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1 equiv), PyBOP (57.3 mg, 0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv), 6-Cl-HOBt (20.9 mg, 0.3 mmol, 3 equiv), DIPEA (51.36 μL, 0.3 mmol, 3 equiv) were dissolved in 0.5 mL DMF and the mixture was stirred for 2 h at RT. The solvent was removed in vacuo to yield a brownish oil. This was dissolved in TFA/TIS/H2O (95/2.5/2.5, v/v/v), stirred for 3 h at RT, precipitated by cold ether, washed two times with ether and dried. The precipitate was purified by preparative HPLC and lyophilized from 80 % tert-BuOH in water (white solid; yield: 55 mg, 0.056 mmol; retention time: 23.1 min; MS calc.: 643.43, found 644.5 (M+H)+).

Phac-Arg-Val-Arg-4-(amidomethyl)-N-amidinopiperidine · 3 TFA (14)

Compound 13 (25 mg, 0.02 mmol, 1 equiv) and 1 H-pyrazole-1-carboxamidine · HCl (9.8 mg, 0.06 mmol, 3 equiv) were dissolved in 0.5 mL DMF and DIPEA (10.03 μL, 0.08 mmol, 4 equiv). The mixture was stirred for 16 h at RT. The solvent was removed in vacuo, the product purified by preparative HPLC and lyophilized from 80 % tert-BuOH in water (white solid; yield: 19.5 mg, 0.019 mmol; retention time: 24.4 min; MS calc.: 685.45, found 343.9 (M+2H)2+).

Phac-Arg-Val-Arg-4-(amidomethyl)benzamidine · 3 TFA (15)

Compound 2 (105.2 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1 equiv), compound 1 (22.21 mg, 0.1 mmol, 1 equiv), PyBOP (57.3 mg, 0.11 mmol, 1.1 equiv), 6-Cl-HOBt (20.9 mg, 0.3 mmol, 3 equiv) and DIPEA (51.36 μL, 0.3 mmol, 3 eq.) were dissolved in 0.5 mL DMF and stirred for 2 h at RT. After completion of the reaction (HPLC control) the solvent was removed in vacuo to give a brownish oil. The synthesis was continued similar to compound 13 (white solid; yield: 70 mg, 0.069 mmol; retention time: 24.2 min; MS calc.: 678,41, found 679.4 (M+H)+).

The synthesis of inhibitors 16-18 was performed in analogy to 15 using decanoic or acetic acid for coupling of the P5 residue. Inhibitor 18 was prepared by coupling of Fmoc-Lys(Cbz)-OH as P2 residue, the Cbz-group was removed in the final step by hydrogenation in 90 % acetic acid at room temperature overnight using Pd/C as catalyst. For analytical data see supporting information.

Enzyme kinetics with furin

The inhibition constants of recombinant soluble human furin25 were determined at room temperature according to the method of Dixon46 using a fluorescence plate reader Safire 2 (Tecan, Switzerland, λex = 380 nm, λem = 460 nm) and pyroGlu-Arg-Thr-Lys-Arg-AMC as substrate (Bachem, Switzerland) in 100 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.0, containing 0.2 % triton X-100, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.02 % sodium azide and 1 mg/ml BSA. The enzyme concentration used in the assay was 0.95 nM, and the substrate concentrations were normally 5, 20 and 50 μM; for inhibitor 15 a fourth substrate concentrations of 12.5 μM was used (Figure 1). The lowest inhibitor concentration was at least 10 times higher than the enzyme concentration used to avoid tight-binding conditions.

Information on enzyme kinetic studies with PC2, PC1/3, PACE4, PC5/6, and PC7 is given in the supplemental material. The Ki-values for the trypsin-like serine proteases thrombin, fXa und plasmin were determined from Dixon-plots as described previously.47

Modeling

Inhibitor 18 was manually docked into the active site cleft of furin and energy minimized using MAIN.48 Basically, the P1-arginine group of the Dec-Arg-Lys-Arg-CMK inhibited mouse furin crystal structure (1p8j.pdb)27 was replaced by 4-amidinobenzylamide and the entire inhibitor was locally energy-minimized using a force field based on the parameters by Engh & Huber,49 while keeping the amidino-moiety coplanar with the benzyl ring and rigidly retaining the coordinates of the enzyme and the Ca2+-ion. During minimization the P4-Arg side chain was forced to retain its crystallographically clearly defined conformation (but apparently somewhat unfavoured by the force field), as previously described.27 Figure 4 was prepared using Grasp,50 MolScript51 and Raster3D.52

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 593 TPB2 and TH 862/1-4) and by NIH (DA05084 to I. Lindberg). We thank Petra Neubauer-Rädel for excellent technical assistance and Sarah Fehling for data analysis of the cell assays.

Abbreviations List

- Ac

acetyl

- Amba

4-amidinobenzylamide

- Cbz

carboxybenzyl

- DCM

dichloromethane

- Dec

decanoyl

- DIPEA

diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- FPV

fowl plaque virus

- HA

all forms of the hemagglutinin

- HBTU

O-benzotriazolyl-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- HOBt

hydroxybenzotriazole

- HPAI virus

highly pathogenic avian influenza virus

- LPAI

low pathogenic or apathogenic influenza virus strains

- MDCK cells

Madin-Darby canine kidney cells

- PFU

plaque-forming units

- Phac

phenylacetyl

- PyBOP

(benzotriazolyl)-N-oxy-pyrrolidinium phosphonium hexafluorophosphate

- SPPS

solid-phase peptide synthesis

- TFA

trifluororacetic acid

- TIS

triisopropylsilane

- THF

tetrahydrofurane

Footnotes

Supporting information available: A table containing MS- and HPLC-data of all final inhibitors, conditions of enzyme kinetic studies with PC2, PC1/3, PACE4, PC5/6, and PC7, conditions of cellular assays to detect virus inhibition, as well as a pdb file of inhibitor 18 modelled in complex with mouse furin is available as supporting information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.van de Ven WJ, Voorberg J, Fontijn R, Pannekoek H, van den Ouweland AM, van Duijnhoven HL, Roebroek AJ, Siezen RJ. Furin is a subtilisin-like proprotein processing enzyme in higher eukaryotes. Mol Biol Rep. 1990;14:265–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00429896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rockwell NC, Krysan DJ, Komiyama T, Fuller RS. Precursor processing by kex2/furin proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4525–4548. doi: 10.1021/cr010168i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fugere M, Day R. Cutting back on pro-protein convertases: the latest approaches to pharmacological inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas G. Furin at the cutting edge: from protein traffic to embryogenesis and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:753–766. doi: 10.1038/nrm934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remacle AG, Shiryaev SA, Oh ES, Cieplak P, Srinivasan A, Wei G, Liddington RC, Ratnikov BI, Parent A, Desjardins R, Day R, Smith JW, Lebl M, Strongin AY. Substrate cleavage analysis of furin and related proprotein convertases. A comparative study. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20897–20906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803762200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Izidoro MA, Gouvea IE, Santos JA, Assis DM, Oliveira V, Judice WA, Juliano MA, Lindberg I, Juliano L. A study of human furin specificity using synthetic peptides derived from natural substrates, and effects of potassium ions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;487:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallenberger S, Bosch V, Angliker H, Shaw E, Klenk HD, Garten W. Inhibition of furin-mediated cleavage activation of HIV-1 glycoprotein gp160. Nature. 1992;360:358–361. doi: 10.1038/360358a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stieneke-Grober A, Vey M, Angliker H, Shaw E, Thomas G, Roberts C, Klenk HD, Garten W. Influenza virus hemagglutinin with multibasic cleavage site is activated by furin, a subtilisin-like endoprotease. EMBO J. 1992;11:2407–2414. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garten W, Hallenberger S, Ortmann D, Schafer W, Vey M, Angliker H, Shaw E, Klenk HD. Processing of viral glycoproteins by the subtilisin-like endoprotease furin and its inhibition by specific peptidylchloroalkylketones. Biochimie. 1994;76:217–225. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(94)90149-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Volchkov VE, Feldmann H, Volchkova VA, Klenk HD. Processing of the Ebola virus glycoprotein by the proprotein convertase furin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:5762–5767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Stroher U, Becker S, Dolnik O, Cieplik M, Garten W, Klenk HD, Feldmann H. Proteolytic processing of Marburg virus glycoprotein. Virology. 2000;268:1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon VM, Klimpel KR, Arora N, Henderson MA, Leppla SH. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins by eukaryotic cells is performed by furin and by additional cellular proteases. Infect Immun. 1995;63:82–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.82-87.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bassi DE, Lopez De Cicco R, Mahloogi H, Zucker S, Thomas G, Klein-Szanto AJ. Furin inhibition results in absent or decreased invasiveness and tumorigenicity of human cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10326–10331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191199198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scamuffa N, Siegfried G, Bontemps Y, Ma L, Basak A, Cherel G, Calvo F, Seidah NG, Khatib AM. Selective inhibition of proprotein convertases represses the metastatic potential of human colorectal tumor cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:352–363. doi: 10.1172/JCI32040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khatib AM, Bassi D, Siegfried G, Klein-Szanto AJ, Ouafik L. Endo/exo-proteolysis in neoplastic progression and metastasis. J Mol Med. 2005;83:856–864. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0692-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassi DE, Fu J, Lopez de Cicco R, Klein-Szanto AJ. Proprotein convertases: “master switches” in the regulation of tumor growth and progression. Mol Carcinog. 2005;44:151–161. doi: 10.1002/mc.20134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller EJ, Caldelari R, Posthaus H. Role of subtilisin-like convertases in cadherin processing or the conundrum to stall cadherin function by convertase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:263–275. doi: 10.1023/b:hijo.0000032358.51866.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett BD, Denis P, Haniu M, Teplow DB, Kahn S, Louis JC, Citron M, Vassar R. A furin-like convertase mediates propeptide cleavage of BACE, the Alzheimer's beta -secretase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37712–37717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stawowy P, Meyborg H, Stibenz D, Borges Pereira Stawowy N, Roser M, Thanabalasingam U, Veinot JP, Chretien M, Seidah NG, Fleck E, Graf K. Furin-like proprotein convertases are central regulators of the membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2 proteolytic cascade in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2005;111:2820–2827. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.502617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bontemps Y, Scamuffa N, Calvo F, Khatib AM. Potential opportunity in the development of new therapeutic agents based on endogenous and exogenous inhibitors of the proprotein convertases. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:631–648. doi: 10.1002/med.20072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basak A. Inhibitors of proprotein convertases. J Mol Med. 2005;83:844–855. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basak A, Lazure C. Synthetic peptides derived from the prosegments of proprotein convertase 1/3 and furin are potent inhibitors of both enzymes. Biochem J. 2003;373:231–239. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apletalina E, Appel J, Lamango NS, Houghten RA, Lindberg I. Identification of inhibitors of prohormone convertases 1 and 2 using a peptide combinatorial library. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26589–26595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron A, Appel J, Houghten RA, Lindberg I. Polyarginines are potent furin inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36741–36749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kacprzak MM, Peinado JR, Than ME, Appel J, Henrich S, Lipkind G, Houghten RA, Bode W, Lindberg I. Inhibition of furin by polyarginine-containing peptides: nanomolar inhibition by nona-D-arginine. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36788–36794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angliker H. Synthesis of tight binding inhibitors and their action on the proprotein-processing enzyme furin. J Med Chem. 1995;38:4014–4018. doi: 10.1021/jm00020a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henrich S, Cameron A, Bourenkov GP, Kiefersauer R, Huber R, Lindberg I, Bode W, Than ME. The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:520–526. doi: 10.1038/nsb941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers JC, Asgian JL, Ekici OD, James KE. Irreversible inhibitors of serine, cysteine, and threonine proteases. Chem Rev. 2002;102:4639–4750. doi: 10.1021/cr010182v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holyoak T, Wilson MA, Fenn TD, Kettner CA, Petsko GA, Fuller RS. Ringe, D. 2.4 A resolution crystal structure of the prototypical hormone-processing protease Kex2 in complex with an Ala-Lys-Arg boronic acid inhibitor. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6709–6718. doi: 10.1021/bi034434t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao GS, Cregar L, Wang J, Millis SZ, Tang C, O'Malley S, Johnson AT, Sareth S, Larson J, Thomas G. Synthetic small molecule furin inhibitors derived from 2,5-dideoxystreptamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19707–19712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606555104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komiyama T, Coppola JM, Larsen MJ, van Dort ME, Ross BD, Day R, Rehemtulla A, Fuller RS. Inhibition of Furin/Proprotein Convertase-catalyzed Surface and Intracellular Processing by Small Molecules. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:15729–15738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901540200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gustafsson D, Bylund R, Antonsson T, Nilsson I, Nystrom JE, Eriksson U, Bredberg U, Teger-Nilsson AC. A new oral anticoagulant: the 50-year challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:649–659. doi: 10.1038/nrd1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinmetzer T, Stürzebecher J. Progress in the development of synthetic thrombin inhibitors as new orally active anticoagulants. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2297–2321. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweinitz A, Stürzebecher A, Stürzebecher U, Schuster O, Stürzebecher J, Steinmetzer T. New substrate analogue inhibitors of factor Xa containing 4-amidinobenzylamide as P1 residue: part 1. Med Chem. 2006;2:349–361. doi: 10.2174/157340606777724040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernatowicz MS, Wu Y, Matsueda GR. 1H-Pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride an attractive reagent for guanylation of amines and its application to peptide synthesis. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1992;57:2497–2502. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiley MR, Chirgadze NY, Clawson DK, Craft TJ, Giffordmoore DS, Jones ND, Olkowski JL, Schacht AL, Weir LC, Smith GF. Serine-protease selectivity of the thrombin inhibitor D-Phe-Pro-Agmatine and its homologs. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1995;5:2835–2840. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garten W, Klenk HD. Cleavage activation of the influenza virus hemagglutinin and its role in pathogenesis. In: Klenk HD, Matrosovich M, Stech J, editors. Avian Influenza. Vol. 27. Karger; Basel: 2008. pp. 156–167. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klenk HD, Garten W. Host cell proteases controlling virus pathogenicity. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:39–43. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garten W, Stieneke A, Shaw E, Wikstrom P, Klenk HD. Inhibition of proteolytic activation of influenza virus hemagglutinin by specific peptidyl chloroalkyl ketones. Virology. 1989;172:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90103-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gustafsson D, Elg M, Lenfors S, Borjesson I, Teger-Nilsson AC. Effects of inogatran, a new low-molecular-weight thrombin inhibitor, in rat models of venous and arterial thrombosis, thrombolysis and bleeding time. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1996;7:69–79. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steinmetzer T, Batdorsdhjin M, Kleinwächter P, Seyfarth L, Greiner G, Reissmann S, Stürzebecher J. New thrombin inhibitors based on D-cha-Pro-derivatives. J Enzyme Inhib. 1999;14:203–216. doi: 10.3109/14756369909030317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schäfer W, Stroh A, Berghofer S, Seiler J, Vey M, Kruse ML, Kern HF, Klenk HD, Garten W. Two independent targeting signals in the cytoplasmic domain determine trans-Golgi network localization and endosomal trafficking of the proprotein convertase furin. EMBO J. 1995;14:2424–2435. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07240.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jean F, Thomas L, Molloy SS, Liu G, Jarvis MA, Nelson JA, Thomas G. A protein-based therapeutic for human cytomegalovirus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2864–2869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050504297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Komiyama T, VanderLugt B, Fugere M, Day R, Kaufman RJ, Fuller RS. Optimization of protease-inhibitor interactions by randomizing adventitious contacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:8205–8210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032865100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jean F, Stella K, Thomas L, Liu G, Xiang Y, Reason AJ, Thomas G. alpha1-Antitrypsin Portland, a bioengineered serpin highly selective for furin: application as an antipathogenic agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7293–7298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon M. The determination of enzyme inhibitor constants. Biochem J. 1953;55:170–171. doi: 10.1042/bj0550170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stürzebecher J, Prasa D, Hauptmann J, Vieweg H, Wikström P. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of potent thrombin inhibitors: piperazides of 3-amidinophenylalanine. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3091–3099. doi: 10.1021/jm960668h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turk D. PhD thesis. Technische Universität München; Germany: 1992. Weiterentwicklung eines Programmes für Molekülgraphik und Elektronendichte-Manipulation und seine Anwendung auf verschiedene Protein-Strukturaufklärungen. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein-structure refeinement. Aacta Crystallogr A. 1991;47:329–400. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraulis PJ. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.