Abstract

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that maternal consumption of polyphenol-rich foods during third trimester interferes with fetal ductal dynamics by inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis.

Study Design:

In a prospective analysis, Doppler ductal velocities and right-to-left ventricular dimensions ratio of 102 fetuses exposed to polyphenol-rich foods (daily estimated maternal consumption >75th percentile, or 1089 mg) were compared with 41 unexposed fetuses (flavonoid ingestion <25th percentile, or 127 mg).

Result:

In the exposed fetuses, ductal velocities were higher (systolic: 0.96±0.23 m/s; diastolic: 0.17±0.05 m/s) and right-to-left ventricular ratio was higher (1.23±0.23) than in unexposed fetuses (systolic: 0.61±0.18 m/s, P<0.001; diastolic: 0.11±0.04 m/s, P=0.011; right-to-left ventricular ratio: 0.94±0.14, P<0.001).

Conclusion:

As maternal polyphenol-rich foods intake in late gestation may trigger alterations in fetal ductal dynamics, changes in perinatal dietary orientation are warranted.

Keywords: echocardiography, ductus arteriosus, prostaglandins

Introduction

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are known to have a constrictive effect on the fetal ductus.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 An increasing number of cases of fetal ductal constriction not associated with consumption of NSAIDs during pregnancy have been observed.6 Previously, we reported that maternal ingestion of polyphenol-rich beverages during pregnancy was associated with fetal ductal constriction and that discontinuation of these substances resulted in echocardiographic improvement in the majority of cases.7, 8

A number of foods and beverages, such as herbal teas, grape and orange derivatives, dark chocolate, berries, and many others have high concentrations of flavonoids and are freely consumed throughout gestation.

Considering that constriction of ductus arteriosus in utero may be clinically important with respect to fetal hemodynamic compromise and the potential for neonatal pulmonary hypertension,9, 10, 11, 12 and that its known pathogenic mechanism is inhibition of maternal circulating prostaglandin synthesis in late pregnancy, we hypothesized that polyphenols or flavonoids present in food and beverages commonly consumed by pregnant women could influence ductal flow dynamics and be a risk factor for ductal constriction. Thus, we compared ductal flow behavior and right ventricular size in third-trimester fetuses exposed and not exposed to polyphenol-rich foods (PRFs) and beverages via maternal consumption.

Methods

Study setting

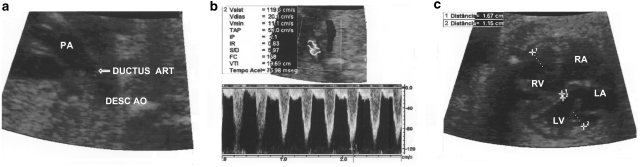

A prospective analysis of 143 consecutive and unselected third-trimester normal fetuses from mothers without systemic diseases was carried out in a period of 4 months. Fetal echocardiography is performed routinely in our center as part of a government sponsored screening program for detection of fetal abnormalities. For fetal Doppler echocardiography, a General Electric Vivid III system, an Acuson Aspen system, or a Siemens Cypress system, with two-dimensional pulsed and continuous Doppler and color flow mapping capability were used. At two-dimensional echocardiography, the ductus arteriosus was imaged in sagittal or longitudinal planes and Doppler velocities were measured by positioning the sample volume in the descending aortic end of the ductus arteriosus, with a maximum insonation angle of 20°. The ratio between the right-to-left ventricular dimensions ratio (RV/LV) was obtained on a four-chamber view in late diastole to assess potential right ventricular pressure changes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Doppler echocardiographic images of ductal systolic and diastolic velocities and right-to-left ventricular dimension ratio in a 29-week fetus whose mother was a heavy green tea consumer. (a) Two-dimensional echocardiographic image of the ductus arteriosus (arrow). (b) Pulsed Doppler spectrum of the ductal flow showing systolic (1.19 m/s) and diastolic (0.20 m/s) velocities in their upper limits. (c) Two-dimensional images of the ventricles showing an increased right-to-left ventricular dimension ratio (1.4). PA, pulmonary artery; Desc Ao, descending aorta; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; DUCTUS ART, ductus arteriosus.

Pregnant women with systemic abnormalities or taking any medicines were excluded from the study. Before echocardiographic examination, a detailed food frequency questionnaire adapted from Block et al.13, 14 was applied by an independent nutritionist. During the nutritional interview, weight and height were also assessed. The total dietary amount of flavonoids was calculated from the USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods,15 considering the 27 items with higher concentrations of polyphenols—>30 mg/100 g of food (green and black tea, mate tea, grape derivatives, dark chocolate, orange juice, fruit teas, olive oil, soy beans, berries, tomato, apples, spinach, and others). A previous local populational survey established a daily amount of polyphenol consumption of 1089.15 mg as the percentile 75 and 127.2 mg as the percentile 25. We considered exposure to PRFs when there was a daily estimated maternal consumption above the 75th percentile (median total flavonoid intake ⩾1089 mg). The group of exposed fetuses was compared with a control group (not exposed), whose maternal daily flavonoid intake was below the 25th percentile (⩽127 mg). At the time of the examination, the observers were blinded to results of the survey on dietary habits.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±s.d. Comparisons between fetal peak systolic and diastolic velocities and RV/LV ratio of exposed and not exposed fetuses were made by two-tailed Student's t-test for independent samples. The relationship between systolic ductal velocity and RV/LV ratio was evaluated by Pearson's linear correlation analysis. Threshold points of systolic and diastolic velocities and RV/LV ratio related to maternal consumption of PRF were determined by ROC curves. Associations and values above cut-off points were tested by two-tailed χ2 test and relative risks were determined with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The α level was set at 0.05 for all statistical tests.

Ethical considerations

This study protocol UP 3888/06 was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Cardiology of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. All patients who were submitted to fetal echocardiographic studies provided informed written consent.

Results

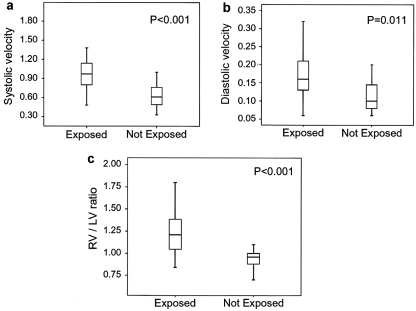

One hundred and forty-three third-trimester normal fetuses from mothers with normal pregnancies were examined to assess the relationship between the consumption of PRF and fetal ductal velocities and RV/LV ratio. Mean maternal age was 30.3±5.4 years (range, 15 to 43 years). Mean gestational ages were 31.2±2.5 weeks (range, 28 to 37 weeks) in the exposed group and 31.8±3.1 weeks (range, 28 to 38 weeks) in the non-exposed group (P>0.5). Mean body mass index was 28.13±3.00 kg/m2. Mean peak systolic velocity was higher in the group of the 102 exposed than in the 41 not exposed fetuses (0.96±0.23 versus 0.61±0.18 m/s, respectively, P<0.001). Mean diastolic velocity was also higher in the exposed group than in the control group (0.17±0.05 versus 0.11±0.04 m/s, respectively, P=0.011). Mean RV/LV ratio was higher in exposed than in not exposed fetuses (1.23±0.23 versus 0.94±0.14, respectively, P<0.001; Figure 2). Systolic ductal velocities were correlated with RV/LV (r=0.64, P<0.001). There was a significant association between maternal consumption of PRFs and beverages and fetal systolic ductal velocity >0.85 m/s (P<0.001, relative risk=8.26, 95% CI, 2.75 to 24.81), diastolic velocity >0.15 m/s (P<0.001; relative risk=2.57; 95% CI, 1.41 to 4.69), and RV/LV >1.1 (P<0.001; relative risk=27.6; 95% CI, 3.96 to 192.01), independently of gestational age.

Figure 2.

Ductal flow velocities and right-to-left ventricular dimension ratio in normal human fetuses: relationship to maternal ingestion of polyphenol-rich beverages and foods. Systolic (a) ductal flow velocities are significantly higher in exposed fetuses. Diastolic (b) ductal velocities are significantly higher in exposed fetuses. (c) The right-to-left ventricular dimension ratios are significantly greater in exposed fetuses.

Discussion

Patency of fetal ductus arteriosus is dependent on the presence of circulating prostaglandins, especially during third trimester.2, 5, 16 Substances with ability to inhibit the prostaglandin biosynthesis pathway may have a constrictive effect on the ductus. It is well known that NSAIDs may inhibit prostaglandin synthesis and cause ductal constriction, with potentially harmful neonatal consequences in the neonatal period, such as pulmonary hypertension.3, 4, 5, 11, 12

The anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids or polyphenols present in commonly consumed beverages and foods have been widely reported in the literature.17, 18, 19, 20, 21 These effects are based on the inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2-mediated transformation of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins and are analogous to those of NSAIDs.

Herbal teas are the second most consumed beverages in the world, accounting for an estimated 0.12 l per year per person.22 Pregnant women frequently consume herbal teas without limitations. Polyphenols in green tea, such as flavonoids or catechins, represent 30 to 40% of the solid leaves extract. The most important catechins present in green tea are epicatechin, gallate-3-epicatechin, epigallocatechin, and gallate-3-epigallocatechin, with epigallocatechin being the predominant catechin present at 7 g per 100 g of dry leaves.15 Their significant antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects have been predominant in many human, animal, and in vitro studies.18, 23, 24 Oral administration of polyphenolic extract of green tea attenuates cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase.17

Mate tea, a beverage rich in polyphenols brewed from dried and minced leaves of Ilex paraguariensis, is widely consumed in South America, even during pregnancy. Its potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities have been associated with the component epigallocatechin gallate, the same compound present in green tea. Epigallocatechin gallate is also believed to be the source of mate tea's proteasome inhibitor activity.19, 25

Resveratrol is a natural polyphenolic molecule present in grape rind and red wine that also has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity attributed to suppression of prostaglandin biosynthesis.20, 26, 27, 28, 29 Grape juice and red wine are consumed daily worldwide. Even though wine consumption is usually low during pregnancy, resveratrol-rich grape juice and derivatives are used without limitations.

Many other foods widely used during pregnancy, such as dark chocolate, orange, berries, red apple, olive oil, soy beans, peanuts, and tomatoes are also rich in polyphenol components.15, 21, 29 We hypothesized that fetal exposure to polyphenol-rich substances would affect ductus arteriosus flow dynamics. Previous studies have shown that a maternal history of consuming PRF with known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties is common in fetuses with ductal constriction.7 It has also been demonstrated that the constrictive effects of both NSAIDs16 and PRF7, 8 on the ductus is ameliorated or completely reversed when these substances are discontinued. Echocardiographic or histological findings of premature ductal constriction were also demonstrated in sheep fetuses exposed to a polyphenol-rich diet for 7 days.30 These changes were probably related to the anti-inflammatory effects of the polyphenol-rich substances on ductus arteriosus dynamics.

In this study, we have established that normal fetuses have higher ductal flow velocities and larger right ventricles when exposed to a maternal polyphenol-rich diet, even when no signs of actual ductal constriction are evident. As our sample was unselected and PRFs are widely consumed during pregnancy, the larger number of patients in the 75th percentile of PRF intake expresses the high PRF consumption pattern in our population. It is unlikely that a recall bias could have influenced the answers provided by mothers about their dietary habits because their interviews preceded the fetal echocardiographic studies. The frequency food questionnaire used in this study has already been validated by Block et al.,13 being the total amount of polyphenols calculated considering the items with higher concentration based on a standard official database for food flavonoid content.15 In addition, examinations were performed by observers who were blinded to the results of the nutritional interview.

The amount of maternal flavonoid ingestion that we considered ‘exposure' was chosen arbitrarily and could be debatable; our objective was to establish objective criteria for habitual consumption. It seems logical to speculate that ductal flow response to polyphenol consumption during pregnancy would not be a categorical parameter but rather a continuous dose-dependent variable; however, this hypothesis has not been tested. The amount of flavonoids necessary to trigger clinically significant fetal ductal constriction as well as the roles of other substances rich in polyphenols consumed during gestation should be investigated in future studies.

‘Idiopathic' neonatal pulmonary hypertension is the third most common etiology of the disease, after meconium aspiration and pneumonia.11, 12 We speculate that many cases could be secondary to in utero ductal constriction caused by exposure to prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, such as PRF. Neonatal follow-up studies after maternal ingestion of PRF during the third trimester might clarify this issue.

The information provided by this study may influence dietary orientation in late pregnancy. Continuing research on the effect of maternal intake of PRFs on ductal flow dynamics and its possible clinical consequences is warranted.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Takami T, Momma K, Imamura S. Increased constriction of the ductus arteriosus by dexamethasone, indomethacin, and rofecoxib in fetal rats. Circ J. 2005;69 3:354–358. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luchese S, Manica JL, Zielinsky P.Intrauterine ductus arteriosus constriction: analysis of a historic cohort of 20 cases Arq Bras Cardiol 2003814405–410.399–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momma K, Hagiwara H, Konishi T. Constriction of fetal ductus arteriosus by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: study of additional 34 drugs. Prostaglandins. 1984;28 4:527–536. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(84)90241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren G, Florescu A, Costei AM, Boskovic R, Moretti ME. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs during third trimester and the risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus: a meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40 5:824–829. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoshima K, Takeda A, Imamura S, Nakanishi T, Momma K. Constriction of the ductus arteriosus by selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 in near-term and preterm fetal rats. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2006;79 1–2:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevett TN, Jr, Cotton J. Idiopathic constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23 5:517–519. doi: 10.1002/uog.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinsky P, Manica JL, Piccoli A, Nicoloso LH, Frajndlich R, Menezes HS, et al. Fetal ductal constriction triggered by maternal. Ingestion of polyphenol-rich common beverages: a clinical approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:258A. [Google Scholar]

- Zielinsky P, Manica JL, Piccoli A, Jr, Nicoloso LH, Frajndlich R, Menezes HS, et al. Ductal flow dynamics right ventricular size are influenced by maternal ingestion of polyphenol-rich common beverages in normal pregnances. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30 4:397. [Google Scholar]

- Jaillard S, Elbaz F, Bresson-Just S, Riou Y, Houfflin-Debarge V, Rakza T, et al. Pulmonary vasodilator effects of norepinephrine during the development of chronic pulmonary hypertension in neonatal lambs. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93 6:818–824. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrue B, Jaillard S, Lorthioir M, Roubliova X, Butrous G, Rakza T, et al. Pulmonary vascular effects of sildenafil on the development of chronic pulmonary hypertension in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol. 2005;288 6:L1193–L1200. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00405.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Marter LJ, Leviton A, Allred EN, Pagano M, Sullivan KF, Cohen A, et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn and smoking and aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug consumption during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1996;97 5:658–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DL, Mills LJ, Weinberg AG. Hemodynamic, pulmonary vascular, and myocardial abnormalities secondary to pharmacologic constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus. A possible mechanism for persistent pulmonary hypertension and transient tricuspid insufficiency in the newborn infant. Circulation. 1979;60 2:360–364. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.2.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block G, Hartman AM, Dresser CM, Carroll MD, Gannon J, Gardner L. A data-based approach to diet questionnaire design and testing. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124 3:453–469. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122 1:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods Release 2.1 Web site: http://wwwarsusdagov/nutrientdata 2007[cited 2 November 2008].

- Vermillion ST, Scardo JA, Lashus AG, Wiles HB.The effect of indomethacin tocolysis on fetal ductus arteriosus constriction with advancing gestational age Am J Obstet Gynecol 19971772256–259.discussion 9–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronikaki AA, Gavalas AM. Antioxidants and inflammatory disease: synthetic and natural antioxidants with anti-inflammatory activity. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2006;9 6:425–442. doi: 10.2174/138620706777698481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Shibata D, Helm J, Coppola D, Malafa M. Green tea polyphenols in the prevention of colon cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:2309–2315. doi: 10.2741/2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinella G, Fantinelli JC, Mosca SM. Cardioprotective effects of Ilex paraguariensis extract: evidence for a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Clin Nutr (Edinburgh, Scotland) 2005;24 3:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Lastra CA, Villegas I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2005;49 5:405–430. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200500022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Giuseppe R, Di Castelnuovo A, Centritto F, Zito F, De Curtis A, Costanzo S, et al. Regular consumption of dark chocolate is associated with low serum concentrations of C-reactive protein in a healthy Italian population. J Nutr. 2008;138 10:1939–1945. doi: 10.1093/jn/138.10.1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham HN. Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry. Prev Med. 1992;21 3:334–350. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90041-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain T, Gupta S, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. Green tea constituent epigallocatechin-3-gallate selectively inhibits COX-2 without affecting COX-1 expression in human prostate carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2005;113 4:660–669. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Oh TY, Kim YK, Baik JH, So S, Hahm KB, et al. Protective effects of green tea polyphenol extracts against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal damages in rats: stress-responsive transcription factors and MAP kinases as potential targets. Mutat Res. 2005;579 1–2:214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixby M, Spieler L, Menini T, Gugliucci A. Ilex paraguariensis extracts are potent inhibitors of nitrosative stress: a comparative study with green tea and wines using a protein nitration model and mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Life Sci. 2005;77 3:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantinelli JC, Schinella G, Cingolani HE, Mosca SM. Effects of different fractions of a red wine non-alcoholic extract on ischemia-reperfusion injury. Life Sci. 2005;76 23:2721–2733. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca SM, Cingolani HE. Cardioprotection from ischemia/reperfusion induced by red wine extract is mediated by K(ATP) channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;40 3:429–437. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200209000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantinelli JC, Mosca SM. Cardioprotective effects of a non-alcoholic extract of red wine during ischaemia and reperfusion in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Experim Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34 3:166–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Actis-Goretta L, Mackenzie GG, Oteiza PI, Fraga CG. Comparative study on the antioxidant capacity of wines and other plant-derived beverages. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;957:279–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielinsky P, Manica JL, Piccoli A, Areias JC, Nicoloso LH, Menezes HS, et al. Experimental study of the role of maternal consumption of green tea, mate tea and grape juice on fetal ductal constriction. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:515. [Google Scholar]