Abstract

Purpose

Randomized multiple myeloma (MM) studies show improved response rates and better progression-free survival for newer therapies. However, a less pronounced effect has been found for overall survival (OS). Using population-based data including detailed treatment information for individual patients, we assessed survival patterns for all patients diagnosed with MM in Malmö, Sweden from 1950 to 2005.

Patients and Methods

We identified 773 patients with MM (48% males). On the basis of the age limit used for treatment with high-dose melphalan with autologous stem-cell support (HDM-ASCT; ≤ 65 years old) in Sweden, we constructed Kaplan-Meier curves and used the Breslow generalized Wilcoxon test to evaluate OS patterns (diagnosed in six calendar periods) for patients 65 years old or younger and patients older than 65 years.

Results

Including all age groups, patients diagnosed from 1960 to 1969 had a better survival than patients diagnosed from 1950 to 1959. In subsequent 10-year calendar periods, median OS increased from 24.3 to 56.3 months (P = .036) in patients ≤ 65 years old. In contrast, OS did not improve among patients older than age 65 years (21.2 to 26.7 months, P = .7).

Conclusion

With the establishment of HDM-ASCT as the standard therapy for younger patients with MM, OS has improved significantly for this age group in the general MM population. With novel therapies being commonly used at disease progression, presumably it becomes increasingly difficult to confirm survival differences between defined induction, consolidation, and maintenance therapies in the future. Consequently, in the era of novel MM therapies, population-based studies will serve as a necessary complement to randomized trials.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disorder that accounts for approximately 1% of all reported neoplasms and 12% to 15% of hematologic malignancies.1 Before the introduction of alkylating agents, median survival time of symptomatic patients with MM was less than 1 year.2 In the early 1960s, melphalan was discovered to have an anti-MM effect, and since then, the combination of melphalan and prednisone (MP) has been the mainstay of therapy in MM.3,4 Combinations including different alkylating agents and low-dose prednisone have not improved survival,5 and interferon, introduced in the late 1970s has only a modest effect on overall survival (OS).6 High-dose melphalan with autologous stem-cell support (HDM-ASCT) in younger patients with MM was introduced in the late 1980s. Since then, seven randomized studies7–13 and one population-based study with historical controls14 have compared this regimen with conventional chemotherapy. Although ASCT has led to improved response rates in all studies and progression-free survival (PFS) in the majority of studies, significantly improved OS was found in only four of eight studies.7,8,10,14 Finally, during the last decade, agents with new mechanisms of action, such as thalidomide,15 bortezomib,16 and lenalidomide,17 have increased the therapeutic arsenal in MM and further improved response rate and PFS. However, although the addition of thalidomide or bortezomib to MP improved OS in some clinical trials,18–20 no significant impact on OS was observed in other trials.21–23

Typically, information on improvements in survival in MM is based on results from randomized studies that generally comprise only a minority of all patients in the recruitment area (in particular, older patients), limiting the generalizability. Currently, there is only limited information on the impact of newer regimens in relation to OS based on the general MM population. A recent study from the Mayo Clinic of 2,981 patients diagnosed between 1971 and 2006 showed evidence of an improved survival mainly in younger patients diagnosed during the past 6 years.24 Given that the Mayo Clinic is a tertiary referral center, the influence of referral bias limits our possibilities to translate the results into the general MM population. However, in support of the Mayo Clinic study, in a population-based study from Sweden, we recently reported evidence of an improved survival among younger patients in recent calendar periods.25 Unfortunately, in our registry-based study, we did not have access to clinical information or treatment data for individual patients. To overcome these limitations, we have conducted a large population-based study with available clinical and treatment data for individual patients. The aim of the present study was to report trends in survival over 56 years in an unselected population of patients with MM.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Universal medical health care has been provided to the entire population in Sweden since the 1950s. Malmö is the third largest city in Sweden. Between 1950 and 2005, the population of Malmö increased from 192,668 to 271,271. Throughout the present study period, the medical care of the population has been served by one main hospital and, during the first three decades, two additional smaller hospitals for geriatric and psychiatric patients. All patients with MM were seen and followed up at Malmö University Hospital, which is the only hospital in the area with an emergency unit and a laboratory unit where all serum protein electrophoresis analyses were performed. To ensure complete patient ascertainment, we used multiple sources to identify patients with MM. For the whole study period, the registries of discharge diagnosis from all three hospitals were searched to identify all reported patients with MM. From 1993, outpatient registries were also searched. Computerized diagnostic registration systems were available for all inpatient care from 1969 and for outpatient care visits from 1993. In 1958, the nation-wide population-based Swedish Cancer Registry was established, and we used this registry in parallel.26 Furthermore, we identified all incident M-proteins detected at the Department of Clinical Chemistry at Malmö from 1950 to 2005. Local autopsy registries from the whole period were also included to trace back information on incident patients with MM not reported elsewhere. In this study, only patients living in Malmö at the time of diagnosis were included.

We obtained available medical records for all patients with a diagnosis of MM, plasmacytoma, or extramedullary plasmacytoma. All records, including bone marrow examinations, serum and urine electrophoresis, and x-ray examinations, were individually reviewed to verify the diagnosis of MM. The minimal criteria for the diagnosis were a monoclonal immunoglobulin in serum or urine (or both) and at least one of the following: ≥ 10% plasma cells and atypical morphology in bone marrow smear, lytic skeletal lesions or pathologic fractures, or hypercalcemia or renal failure with no other explanation than the plasma cell dyscrasia. Patients without an observed M-protein in serum or urine were accepted if they had histologic evidence of plasma cell proliferation and typical skeletal lesions or were diagnosed first on autopsy and no serum or urine protein electrophoresis was performed. Patients with solitary plasmacytoma were included only if they developed generalized myeloma. All patients had a clinical picture compatible with MM.

Survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis until the date of death, loss to follow-up, or end of study (August 31, 2008), whichever occurred first. Patients diagnosed at autopsy were excluded from this analysis. OS curves for patients diagnosed in six calendar periods (1950 to 1959, 1960 to 1969, 1970 to 1979, 1980 to 1989, 1990 to 1999, and 2000 to 2005) were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Breslow generalized Wilcoxon method was used to test for statistical differences. The survival analysis was performed separately for two age cohorts (≤ v > 65 years) based on the age limit used for application of HDM-ASCT.

For patients with MM diagnosed in 1970 or later, primary treatment was registered and grouped in the following three categories: MP-like (MP or other combinations with alkylating agents); vincristine-doxorubicin-dexamethasone–like or other high-dose corticosteroid-based regimens; and no anti-MM treatment or only radiotherapy/surgery. In addition, HDM-ASCT and the use of thalidomide as part of primary treatment (MP + thalidomide) were registered. For all patients, we captured information whether or not the patient received thalidomide as salvage therapy. Before 2006, few MM patients received bortezomib or lenalidomide in Sweden.

RESULTS

A total of 773 patients with MM (373 men and 400 women) were diagnosed in Malmö between January 1, 1950 and December 31, 2005. Among these patients, 13 patients (1.7%) were diagnosed at autopsy. In August 2008, 742 patients had died, and 29 were alive. Two patients were lost to follow-up. Median OS for all patients diagnosed in the study period was 22.2 months. Men had a shorter median OS than women (18.6 and 26.3 months, respectively; P = .003). Patients ≤ 65 years old at diagnosis had a better median OS compared with patients diagnosed at ≥ 66 years old (35.1 and 18.2 months, respectively).

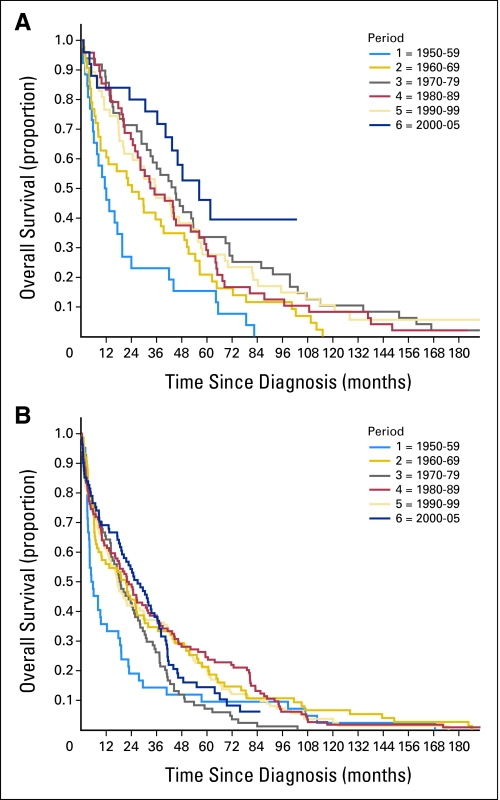

In Figure 1, OS curves for patients with MM diagnosed in six calendar periods are shown by age (≤ v > 65 years). There was a marked improvement in OS in patients diagnosed from 1960 to 1969 compared with patients diagnosed from 1950 to 1959. This was true for both age groups. When analyzing patients diagnosed after 1960, the median OS did not change significantly in patients older than age 65 years (21.2 months for patients diagnosed from 1960 to 1969 and 26.7 months for patients diagnosed from 2000 to 2005, χ2 = 2.187, P = .7). In patients 65 years old and younger at diagnosis, OS increased from 24.3 months to 56.3 months in patients diagnosed from 1960 to 1969 and 2000 to 2005, respectively (χ2 = 10.254, P = .036). The major improvement was in the most recent calendar period (2000 to 2005).

Fig 1.

Overall survival in patients with multiple myeloma according to date of diagnosis and age at diagnosis: (A) ≤ 65 years old (n = 242) and (B) > 65 years old (n = 431). Periods of diagnosis were as follows: 1 = 1950 to 1959; 2 = 1960 to 1969; 3 = 1970 to 1979; 4 = 1980 to 1989; 5 = 1990 to 1999; and 6 = 2000 to 2005.

Melphalan was introduced in the treatment of MM in the early 1960s. It was initially given as a continuous daily dose and, from the 1970s, was gradually exchanged for the combination with prednisone (MP). Detailed information on the primary treatment of each patient was available in all patients diagnosed in 1970 and later (n = 581); this information is shown in Table 1. Among patients diagnosed after age 65 years, MP-like therapy was the most dominant primary treatment in all calendar periods. Among patients diagnosed at age 65 years or younger, vincristine-doxorubicin-dexamethasone–like therapy (including other high-dose corticosteroid-based regimens) was gradually introduced in the primary treatment during the 1990s and was given to 96% of patients in the last calendar period. As shown in Table 1, HDM-ASCT was administered to 25% and 84% of patients ≤ 65 years old diagnosed in 1990 to 1999 and 2000 to 2005, respectively. During 2000 to 2005, thalidomide was used in 32.0% and 23.5% of patients in the younger and older age groups, respectively, either as part of the primary treatment (in combination with MP) or as a salvage therapy.

Table 1.

Distribution of Patients Receiving Various Types of Initial Therapies and Thalidomide Salvage Treatment According to Age and Year of Diagnosis

| Initial Treatment | Age ≤ 65 Years at Diagnosis (% of patients) |

Age > 65 Years at Diagnosis (% of patients) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970-1979 (n = 49) | 1980-1989 (n = 48) | 1990-1999 (n = 48) | 2000-2005 (n = 25) | 1970-1979 (n = 85) | 1980-1989 (n = 114) | 1990-1999 (n = 124) | 2000-2005 (n = 81) | |

| MP or MP-like | 95.9 | 95.8 | 62.5 | 4 | 85.9 | 85.3 | 76.8 | 84.0 |

| VAD or VAD-like | 0 | 0 | 29.2 | 96.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.9 |

| No treatment | 4.1 | 4.2 | 8.3 | 0 | 7.1 | 12.4 | 22.6 | 11.1 |

| HDM + ASCT | 0 | 0 | 25.0* | 84.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 |

| Thalidomide in salvage treatment | 0 | 0 | 29.2 | 32.0 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 23.5 | |

Abbreviations: MP, melphalan and prednisone; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone; HDM, high-dose melphalan; ASCT, autologous stem-cell support.

Patients were induced with VAD before HDM.

DISCUSSION

There are two main observations in the present study. First, the median OS of patients with MM ≤ 65 years old at diagnosis has more than doubled since the 1960s, with the major improvement occurring during the last calendar period (2000 to 2005). Second, there has been only a modest improvement in OS, not reaching statistical significance, in patients older than age 65 years at diagnosis. Combination chemotherapy, interferon, and improvements in supportive care such as bisphosphonates and erythropoietin have had a limited impact on survival in this age group.

After its introduction, treatment with HDM-ASCT was given to the vast majority of MM patients ≤ 65 years old but to few patients older than age 65 who were diagnosed from 2000 to 2005. As a result, in our study, we stratified our models by age greater than versus less than or equal to 65 years. In the last calendar period, among younger patients, thalidomide was given mainly as salvage treatment to approximately one third of patients. Among older patients, the corresponding fraction was approximately one fourth. Although it cannot be excluded that thalidomide may have contributed to the improved OS observed in younger patients with MM, it seems less likely considering the limited number of patients treated and the absence of impact on OS in the older age group.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report on trends in OS in an unselected MM population over a long time period, where the diagnosis was confirmed by careful review of all records and detailed information on primary treatment for individual patients was obtained. Our results are in accordance with those from a previous population-based registry study (including all patients with MM diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003 and reported to the Swedish Cancer Registry) conducted by our group.25 In that registry-based study, 1-year survival of patients with MM increased over all age groups, but improvement of 5- and 10-year survival was confined to patients younger than age 70 years and most marked in the last calendar period (1994 to 2003). As already stated, unfortunately, the registry study did not include details on therapy for individual patients. Similarly, another recent registry study from the United States, using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program, found evidence of improved 5- and 10-year OS among patients with MM younger than age 60 years who were diagnosed from 2002 to 2004 compared with patients diagnosed from 1992 to 1994.27 In the age group of 60 to 69 years, only a moderate improvement was seen, and essentially no improvement was achieved among older patients. In a registry-based study from the Greek Myeloma Study Group, OS increased mainly among younger patients after introduction of thalidomide.28 Similar to the previous Swedish Cancer Registry–based study, none of these studies had information on therapy for individual patients. In a clinic-based study from the Mayo Clinic, based on 2,981 patients with MM diagnosed from 1971 to 2006 (without therapeutic data for individual patients), there was no change in the median OS in the first four 6-year periods but a significant improvement in the past 6 years.24 The improvement in survival was seen predominantly among patients younger than age 65 years at diagnosis, with a median OS of 60 months in the last calendar period, which is similar to the median OS of 56.3 months in patients ≤ age 65 years in our study.

The observations that outcome is better in women than in men and that older age is an unfavorable prognostic factor for survival are in accordance with previous studies.25 A somewhat unexpected observation in our study was the relatively high proportion of patients who did not receive anti-MM treatment (58 of 574 patients, 10.1%). Of these patients, 24 had asymptomatic disease and died from causes that were not related to MM. Very high age, severe comorbidity, and early death (within weeks) were the reasons for not receiving any anti-MM treatment in 34 patients. This group of patients is underrepresented in randomized studies.

The strengths of our study are the unselected MM population, the active efforts to achieve a complete ascertainment of patients, the review of all records to confirm the diagnosis, and the detailed information on treatment in individual patients, including information that cannot be easily controlled or obtained in registry-based studies. The median age at diagnosis was higher in our study (72 years) than in the two other registry-based studies from Sweden and the United States (69.9 and 70 years, respectively).25,27 In the Mayo Clinic cohort, the median age at diagnosis was 66 years.24

Limitations of our study include the small number of patients, which made the survival curves less stable. We also had limited access to data on prognostic markers (such as β2-microglobulin and cytogenetics). Also, it cannot be excluded that changes in survival, at least to some degree, are influenced by changes in diagnostic practice and access to health care, causing earlier detection of the disease. The age-adjusted incidence of MM in Malmö, Sweden was stable over the entire time period studied, arguing against such changes (Turesson et al, submitted for publication), and virtually all patients were treated at the same university hospital during the whole period. However, the proportion of very old patients increased over time, and this could influence survival in the age group greater than 65 years old. It cannot be ruled out that non–treatment-related changes over time may have influenced the results. Also, survival changes over time in the general population might have impacted our results.

Although most randomized studies have reported improved survival with HDM-ASCT compared with conventional treatment, others have not been able to confirm these results.10–13 Also, in five randomized studies comparing MP plus thalidomide with MP alone and reporting improved response rates and PFS, only two have observed a significant impact on OS,18,19 whereas in three studies, there was no significant prolongation of survival.21–23 One explanation for this lack of impact on OS is that a high proportion of patients with MM receive an active novel agent at relapse. In a study of HDM-ASCT from the United States, there was no significant improvement in OS compared with conventional treatment.13 This can most likely be explained by the fact that the study design recommended high-dose treatment at relapse in the conventional treatment arm. Indeed, the use of newer treatment strategies at progression makes it difficult to interpret OS as an end point in randomized studies.

In conclusion, in an unselected population of patients with MM diagnosed between 1950 and 2005, we found an improved OS for patients diagnosed from 1960 to 1969 compared with patients diagnosed from 1950 to 1959. In later calendar periods, a doubling of median OS was observed for patients ≤ age 65 years, with the major improvement occurring in the last calendar period, but we found no significant improvement in survival in patients older than age 65 years at diagnosis. The most likely explanation for our observations is the introduction of HDM-ASCT in the younger age group. At this time, there is no doubt that future studies with longer observation are needed to evaluate the impact of the newer drugs such as thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide on OS in MM. Simultaneously, there are inherent limitations in future clinical MM trials. Given that the treatment strategies for MM are currently changing and newer therapies are commonly used at disease progression, most patients with MM will eventually receive all available novel drugs; mainly, the sequence of different regimens will vary. Consequently, it will become harder to establish survival differences between defined induction, consolidation, and maintenance therapies in the future. Thus, valid treatment comparisons focusing on OS as the outcome will require larger and more expensive trials with longer follow-up intervals. For these reasons, it seems logical to believe that population-based studies with detailed treatment information for individual patients will become increasingly important and a necessary complement to randomized trials in MM. Such studies will allow us to better evaluate survival benefits in patients with MM in the era of novel therapies.

Acknowledgment

We thank Jan Åke Nilsson, PhD, for help with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute and by grants from the Foundation for Research on Blood Diseases, Malmö, Sweden.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ingemar Turesson, Ramon Velez, Ola Landgren

Collection and assembly of data: Ingemar Turesson

Data analysis and interpretation: Ingemar Turesson, Ramon Velez, Sigurdur Y. Kristinsson, Ola Landgren

Manuscript writing: Ingemar Turesson, Ramon Velez, Sigurdur Y. Kristinsson, Ola Landgren

Final approval of manuscript: Ingemar Turesson, Ramon Velez, Sigurdur Y. Kristinsson, Ola Landgren

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics 2000. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osgood E. The survival time of patients with plasmacytic myeloma. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1960;9:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergsagel DE, Sprague CC, Austin C, et al. Evaluation of new therapeutic agents in the treatment of multiple myeloma: IV. L-phenylalanine mustard (NSC-8806) Cancer Chemother Rep. 1962;21:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexanian R, Haut A, Khan A, et al. Treatment for multiple myeloma: Combination therapy with different melphalan dose regimens. JAMA. 1969;208:1680–1685. doi: 10.1001/jama.208.9.1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myeloma Trialists' Collaborative Group. Combination chemotherapy versus melphalan plus prednisone as treatment for multiple myeloma: An overview of 6633 patients from 27 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:3832–3842. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.12.3832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myeloma Trialists' Collaborative Group. Interferon as therapy for multiple myeloma: An individual patient data overview of 24 randomized trials and 4012 patients. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:1020–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attal M, Harousseau JL, Stoppe AM, et al. A prospective, randomized trial of autologous bone marrow transplantation and chemotherapy in multiple myeloma: Intergroupe Francais du Myelome. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:91–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607113350204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Child JA, Morgan GJ, Davies RE, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell rescue for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1875–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fermand JP, Ravaud P, Chevret S, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma: Up-front or rescue treatment? Results of a multicenter sequential randomized clinical trial. Blood. 1998;92:3131–3136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Petrucci MT, et al. Intermediate-dose melphalan improves survival of myeloma patients aged 50 to 70: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood. 2004;104:3052–3057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bladé J, Rosinol L, Sureda A, et al. High-dose therapy intensification compared with continued standard chemotherapy in multiple myeloma patients responding to the initial chemotherapy: Long-term results from a prospective randomized trial from the Spanish cooperative group PETHEMA. Blood. 2005;106:3755–3759. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fermand JP, Katsahian S, Divine M, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous blood stem-cell transplantation compared with conventional treatment in myeloma patients aged 55 to 65 years: Long-term results of a randomized control trial from the Group Myelome-Autogreffe. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9227–9233. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlogie B, Kyle RA, Anderson KC, et al. Standard chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemoradiotherapy for multiple myeloma: Final results of phase III US Intergroup Trial S9321. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:929–936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lenhoff S, Hjorth M, Holmberg E, et al. Impact on survival of high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell support in patients younger than 60 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: A population-based study—Nordic Myeloma Study Group. Blood. 2000;95:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singhal S, Mehta J, Desikan R, et al. Antitumor activity of thalidomide in refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1565–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199911183412102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2609–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Weller E, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-50213 overcomes drug resistance and is well tolerated in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100:3063–3067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Facon T, Mary JY, Hulin C, et al. Melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide versus melphalan and prednisone alone or reduced-intensity autologous stem cell transplantation in elderly patients with multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2007;370:1209–1218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulin C, Facon T, Rodon P al. Efficacy of melphalan and prednisone plus thalidomide in patients older than 75 years with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: IFM 01/01 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3664–3670. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.San Miguel J, Schlag R, Khuageva N, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:906–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Liberati AM, et al. Oral melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: Updated results of a randomized controlled trial. Blood. 2008;112:3107–3114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waage A, Gimsing P, Juliusson G, et al. Melphalan-prednisone-thalidomide to newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma: A placebo-controlled randomized phase 3 trial. Blood. 2007;110:78. abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wijermans P, Schaafsma M, van Norden Y, et al. Melphalan + prednisone versus melphalan + prednisone + thalidomide induction therapy for multiple myeloma in elderly patients: Final analysis of the Dutch cooperative group HOVON 49 study. Blood. 2008;112:649. abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kristinsson SY, Landgren O, Dickman PW, et al. Patterns of survival in multiple myeloma: A population-based study of patients diagnosed in Sweden from 1973 to 2003. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1993–1999. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattsson B, Wallgren A. Completeness of the Swedish Cancer Register: Non-notified cancer cases recorded on death certificates in 1978. Acta Radiol Oncol. 1984;23:305–313. doi: 10.3109/02841868409136026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Recent major improvement in long-term survival of younger patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111:2521–2526. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kastritis E, Zervas K, Symeonides A, et al. Improved survival of patients with multiple myeloma after the introduction of novel agents and the applicability of the International Staging System (ISS): An analysis of the Greek Myeloma Study Group (GMSG) Leukemia. 2009;23:1152–1157. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]