Abstract

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) permanently alters bladder function in humans. Hematuria and cystitis occur in both human SCI as well as in rodent models of SCI. Others have reported early SCI-dependent disruption to bladder uroepithelial integrity that results in increased permeability to urine and urine-borne substances. This can result in cystitis, or inflammation of the bladder, an ongoing pathological condition present throughout the chronic phase of SCI in humans. The goals of our study were twofold: (1) to begin to examine the inflammatory and molecular changes that occur within the bladder uroepithelium using a clinically-relevant spinal contusion model of injury, and (2) to assess whether these alterations continue into the chronic phase of SCI. Rats received either moderate SCI or sham surgery. Urine was collected from SCI and sham subjects over 7 days or at 7 months to assess levels of excreted proteins. Inflammation in the bladder wall was assessed via biochemical and immunohistochemical methods. Bladder tight junction proteins, mediators of uroepithelial integrity, were also measured in both the acute and chronic phases of SCI. Urine protein and hemoglobin levels rapidly increase following SCI. An SCI-dependent elevation in numbers of neutrophils within the bladder wall peaked at 48 h. Bladder tight junction proteins demonstrate a rapid but transient decrease as early as 2 h post-SCI. Surprisingly, elevated levels of urine proteins and significant deficits in bladder tight junction proteins could be detected in chronic SCI, suggesting that early pathological changes to the bladder may continue throughout the chronic phase of injury.

Key words: bladder permeability, hematuria, inflammation, recovery, spinal cord injury

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (sci) induces a wide range of pathological events, generally resulting in a permanent state of sensory and motor loss (Hulsebosch, 2002; Norenberg et al., 2004). In addition to these well-described pathological alterations, traumatic SCI produces severe deficits within the urogenital system (Craggs et al., 2006; Samson and Cardenas, 2007). The majority of these deficits are the result of disruption of supraspinal input, afferent input to the spinal cord, and reorganization of intraspinal circuitry in response to injury (Vizzard 1999; Yu et al., 2003). Functionally these deficits can include detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, hyperreflexia, and autonomic dysreflexia, conditions that are both chronic and potentially life-threatening (Birder, 2006; Samson and Cardenas, 2007; Tai et al., 2006).

The urinary bladder can undergo significant structural, physiological, and molecular alterations following SCI (Apodaca et al., 2003; Samson and Cardenas, 2007; Toosi et al., 2008). Normally the bladder is responsible for both the storage and the expulsion of urine from the body. The walls of the bladder are covered in a layer of tissue called the uroepithelium. The uroepithelium is a multi-cellular layer that covers the underlying bladder mucosa and provides a barrier that retains and prevents the paracellular flow of urine and urine components into the underlying mucosa and bloodstream (Birder, 2004). Within the uroepithelium, specialized umbrella cells align and face the lumen, acting as the key regulator of barrier function (Birder, 2004; Birder and de Groat, 2007). These umbrella cells are interconnected via a network of tight junction proteins, including occludin and several members of the claudin family (Acharya et al., 2004; Apodaca et al., 2003). These tight junctional proteins contribute to the barrier's high transepithelial resistance and low permeability to water, as well as to urine and urine-associated solutes (Acharya et al., 2004; Apodaca et al., 2003; Birder and de Groat, 2007).

Humans who have suffered SCI can exhibit sustained ulceration as well as other abnormalities of the bladder uroepithelium (Janzen et al., 2001, 1998), that can leave the bladder vulnerable to chronic cystitis or inflammation, possibly related to chronic bacterial infections. Hemorrhagic cystitis can often occur in animal models of SCI (Apodaca et al., 2003), potentially resulting in long-term abnormalities in bladder structure. Apodaca and colleagues have shown that SCI rapidly elicits alterations in the bladder uropithelium (Apodaca et al., 2003). They described rapid alterations in the umbrella cell layer of the uroepithelium, a dramatic drop in transepithelial resistance, and an increase in permeability to water, all indicators of uroepithelial barrier failure (Apodaca et al., 2003). Many of these changes appeared to be transient, with restoration of near-normal values by around 28 days post-injury.

Patients with SCI currently face a lifetime of sensory and motor deficits. Bladder care issues represent a substantial problem for chronic SCI sufferers (Hung et al., 2007; Janzen et al., 1998, 2001; Scheff et al., 2003). Here we describe an initial study of the response of the rat bladder to SCI using a clinically-relevant contusion model. We describe several morphological and biochemical changes that occur to the bladder throughout the early acute phase of SCI. In addition we report novel findings that indicate that the rodent bladder exhibits characteristics of barrier dysfunction at 7 and 10 months post-SCI. These studies suggest that SCI-dependent bladder barrier dysfunction is not restricted to the early acute phase of injury, but rather may exhibit structural and biochemical deficits that may influence barrier function well into the chronic phase post-injury, if not permanently.

Methods

Animal subjects and surgeries

A total of 29 adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (225–250 g) were used in this study. All moderate spinal cord contusions were performed under anesthesia consisting of a mixture of ketamine (80 mg/kg), xylazine (10 mg/kg), and acepromazine (0.75 mg/kg), at a dose of 0.1 mL/100 g body weight. Spinal contusion surgeries were performed using the Infinite Horizon spinal injury device (Precision Systems and Instrumentation, LLC, Lexington, KY) (Scheff et al., 2003). Briefly, a laminectomy was performed at T10 and the vertebral column was stabilized using Adson forceps clamping at T9 and T11. A moderate-to-severe contusion injury was performed using 150 kDyn of force with a 1-sec dwell time. Immediately following injury, the overlying muscles were sutured and the skin was closed with stainless steel wound clips. The animals were sacrificed in the acute phase of injury at 2, 6, 24, 48, 72 h, and 7 days post-SCI (n = 4/time point), or at 10 months post-SCI (n = 12 chronic SCI; n = 5 uninjured age-matched controls). Postoperative care for the first 1–7 days included the manual expression of bladders twice daily. Subjects received intraperitoneal fluids (2–3 mL of 0.9% saline) twice daily to promote hydration for the first 72 h. Subjects also received postoperative antibiotics (2.5 mg/kg Baytril®) twice daily for 10 days to prevent infection. Chronically-injured subjects were placed on a twice-daily regimen of Baytril for 7 days prior to urine collection to minimize the risk of bladder wall deficits resulting from infection. Sham-control animals (n = 4) received the laminectomy only without contusion, but underwent an identical regimen of postoperative care as that of injured animals. Sham-control animals were sacrificed at the 72-h time point. All animal experiments were carried out with the approval of the University of Texas Health Science Center's Institute for Animal Care and Use Committee, as well as under the guidelines of the Society for Neuroscience's Guide for the Care and Use of Animal Subjects.

Bladder and urine processing

The animals were euthanized with beuthanasia (75 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The bladders were excised and separated into three regions: the bladder dome and the left and right sides. The right and left sections of the bladder were used for Western blot analysis and myeloperoxidase activity analysis, respectively. The bladder dome was used for histological analysis. The excised bladders were minced and homogenized in homogenization buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail for mammalian tissue (P8340; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) at 4°C. Bladder samples were homogenized using a motor-driven Teflon probe. After 20 sec of homogenization, the samples were placed back on ice. Bladder samples were then sonicated and centrifuged (20,000g for 1 h at 4°C). Supernatant samples were frozen and stored at −20°C. All samples were processed on the same day to avoid changes in sample preparations.

Urine was collected in sterile tubes twice daily by firm palpation of the bladder and stored at −20°C. Urine samples were assayed for hemoglobin to assess hematuria. Overall protein levels in the urine were assayed using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA).

Western blot analysis

The amount of protein in each sample was measured using a Bradford assay employing bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. The samples were prepared by boiling in sample buffer, and equal amounts of protein were resolved in a 4–20% Tris-HEPES-SDS gel from Pierce Protein Research Products (Rockford, IL). To further control for protein loading, the samples were then normalized using a Coomassie-stained gel. The samples were normalized using ImageJ gel analysis software version 1.34. Equal amounts of proteins were resolved in a 4–20% Tris-HEPES-SDS gel, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% BSA in TBST (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 150 mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20). Immunoreactivity was assessed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescence. The quantification of the immunoreactive bands was performed using ImageJ software. The following primary antibodies (each used at 3 μg/mL) were obtained from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA): claudin-5 (cat. no. 35-2500), occludin (cat. no. 71-1500), and ZO-1 (cat. no. 40-2200). β-Actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used a loading control.

Hemoglobin assay

Quantification of hemoglobin in the urine samples was performed as previously described (Crosby and Furth, 1956) with slight modification. Briefly, hemoglobin standards were prepared in 0.9% saline. Urine samples (25 μL) were then mixed with equal volumes of benzidine reagent and 1% hydrogen peroxide. The samples were incubated for 20 min at room temperature. After the incubation period, 5 mL of 10% acetic acid was added. The samples were mixed and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were then analyzed and hemoglobin concentrations determined using a Bio-Rad spectrophotometer at 515 nm. All samples were performed in triplicate.

Myeloperoxidase assay

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity (a marker for the presence of neutrophils) was quantified using a method described previously (Ginzberg et al., 2001). Briefly, peroxidase standards were prepared in hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB) buffer in 50 mM KH2PO4 pH adjusted to 6.0 using 50 mM Na2HPO4 (Sigma-Aldrich no. H5882). The samples were homogenized in HTAB solution and underwent a rapid freeze-thaw procedure three times. The samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was used in the remaining MPO assay. Samples (20 μL in triplicate) were mixed with 200 μL of TMB reagent (Sigma-Aldrich no. T8665), and incubated in the dark for 15 min at room temperature. The reactions were stopped using 2 N HCl, and the samples were then read at 450 nm. Peroxidase concentrations were determined using Microplate Reader software from Bio-Rad.

Immunohistology

Following excision and dissection, the bladder domes were drop-fixed into 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Bladder dome tissues were then cryo-protected by immersion in 30% sucrose, and cut on a cryostat at a thickness of 30 μm. Serial sections were direct-mounted onto glass slides for immunohistological analysis. The presence of neutrophils in the bladder uroepithelium was assessed by immunofluorescent staining of bladder tissue using a rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against human MPO (Dako North America, Inc., Carpenteria, CA). MPO was visualized using the appropriate secondary antibody linked to Alexafluor 568 dye (Invitrogen). Tissue sections were counterstained using the fluorescent nucleic acid dye Sytox Green (Invitrogen; 1:15,000 concentration) to clearly define the epithelial layer of the bladder wall. As a control for antibody specificity, the primary antibody was excluded, and only the fluorescently-linked secondary antibody was applied.

Fluorescently-labeled sections were imaged using a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 confocal system attached to an Olympus BX-50 upright microscope. A computer-controlled z-stage allowed the collection of stacks of optical sections, to examine the co-localization of fluorescent markers. Typically, we assessed fluorescent labeling by generating image stacks sequentially in the z-plane over 10–15 optical sections, with intermittent step sizes up to 0.5 μm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of urine protein levels at acute time points was performed using a one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test; the Student's t-test was performed on chronic samples. Other statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's multiple range test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Results

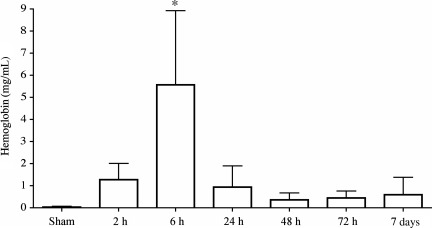

Hematuria occurs rapidly following spinal contusion injury

Injury to the spinal cord commonly results in rapid hematuria, which may be observed over the course of several days post-injury (Apodaca et al., 2003). We detected hemoglobin, a key indicator of blood and blood-breakdown products, in the urine as early as 2 h post-SCI (Fig. 1). Hemoglobin levels peaked by 6 h post-SCI (p = 0.0395), then returned to near-sham levels between 24 h and 7 days post-injury. Sham animals experienced bladder expression as well, to rule out the possibility that pressure from the manual expression of urine was the source of hematuria.

FIG. 1.

Quantitative analysis of hemoglobin in the urine post-SCI. Hemoglobin levels increased 2 h after injury and reached peak levels by 6 h post-injury (*p = 0.0395). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey's multiple range test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. The samples were run in triplicate (n = 4/time point).

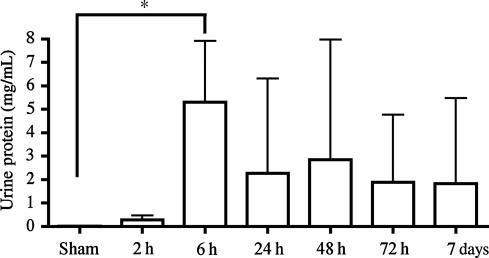

Gross protein in the urine in the acute phase of SCI

In addition to hemoglobin, we also assessed gross protein levels in the urine as an indicator of barrier failure in the bladder and/or the upper urinary tract via Bradford assay. Similarly to hemoglobin, we detected an increase in protein in the urine within 2 h of SCI, compared to sham-injured animals (Fig. 2). Protein levels in the urine reached a peak by 6 h (p = 0.0247). Interestingly, overall levels of protein remained elevated, though not significantly, out to 7 days post-SCI. This differs from the results of the hemoglobin assay, and may indicate a more generalized permeability to a wider range of proteins following SCI, or was due to differences in sensitivity of the assay methods.

FIG. 2.

Urine protein quantification following spinal cord injury. Bradford assays performed on the urine samples indicated a significant increase in the amount of protein present in the urine at 6 h post-injury (*p = 0.0247). The protein concentrations from 24 h to 7 days also appeared to be elevated, but due to high variability these did not reach statistical significance. Statistical analysis on acute time points were performed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by a Dunn's multiple comparison test. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05 (n = 4 subjects/time point).

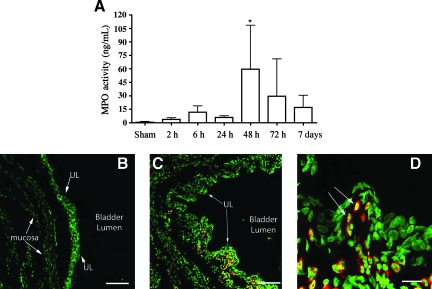

Quantification of neutrophil influx into the bladder after SCI

The increased urine protein levels, including hemoglobin, suggested a compromised uroepithelium. We wished to examine SCI-dependent changes occurring within the bladder uroepithelium during the acute phase of injury. Neutrophils expressing MPO are a blood-borne population of immune cells that rapidly respond to trauma and damage (Chin and Parkos, 2007), serve as an indicator of an early inflammatory response, and can be measured via MPO enzymatic activity. MPO activity in the bladder tissue of sham animals was negligible (Fig. 3). Following SCI, MPO activity could be detected in bladder samples as early as 2 h post-injury (Fig. 3). MPO activity was significantly elevated by 48 h post-contusion (p = 0.0077). MPO levels began to diminish by 72 h, but remained elevated over levels in control animals by 7 days (not significant). MPO-immunoreactivity (MPO-IR) was absent in the bladder walls harvested from sham animals at 48 h following surgery (Fig. 3B). Large numbers of MPO-IR cells were found throughout both the uroepithelium and underlying tissues of the bladder at 48 h after SCI (Fig. 3C and D).

FIG. 3.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and distribution in the bladder following spinal cord injury. (A) MPO activity was increased 2 h after injury, reaching statistical significance by 48 h (*p = 0.0077), before returning to normal levels compared to sham animals. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Dunn's multiple comparable test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. (B) Immunohistochemical detection of MPO in bladder tissue. The bladder from a sham-injured animal immunolabeled using an antibody against myeloperoxidase (red). Nuclei were counterstained with Sytox green nucleic acid stain. (C) Large numbers of MPO-immunoreactive neutrophils were found in the bladder at 48 h after spinal contusion injury. Neutrophils were observed at the level of the uroepithelial layer (UL), as well as in the underlying mucosa. (D) High-magnification image showing large numbers of neutrophils within the uroepithelium (scale bars in B and C = 100 μm, and in D = 20 μm; n = 4 subjects/time point).

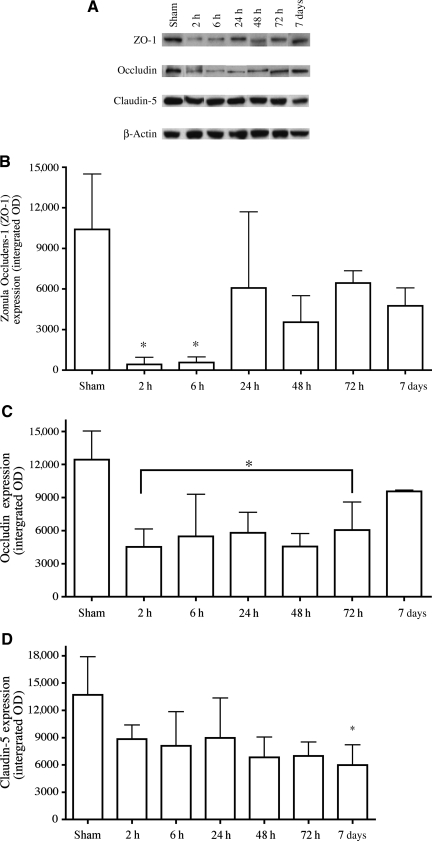

Changes in bladder tight junction proteins in the acute phase of SCI

The barrier properties of the uroepithelium are largely dependent upon a network of tight junction proteins that link the superficial umbrella cells to each other. Loss of this network could result in a dysfunctional barrier and increased permeability to urine. Inflammation has previously been shown to cause tight junction protein rearrangements and enhanced permeability in a number of systems (Patrick et al., 2006; Xu et al., 2005), both in vitro and in vivo (Brooks et al., 2005). We quantitatively examined the expression levels of two tight junction proteins, occludin and claudin-5, at time points ranging from 2 h to 7 days post-SCI, via Western blot analysis (Fig. 4A). In addition, we also explored the expression of the submembranous protein zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a protein that links several tight junction proteins to the underlying actin cytoskeleton. ZO-1 protein was significantly decreased at both 2 and 6 h post-injury (p = 0.0007), but was not statistically significantly different from sham levels by 24 h (Fig. 4B). Occludin levels in the bladder were reduced threefold by 2 h post-SCI (Fig. 4C). Occludin protein levels remained statistically significantly reduced compared to shams out to 72 h (p = 0.003), but were not statistically significantly different from sham animals by 7 days post-injury. SCI elicited only a slight reduction in claudin-5 in the bladder compared to sham animals (Fig. 4D). Claudin-5 appears to exhibit a delayed reduction compared to occludin and ZO-1, only achieving a significant level of difference from sham animals by 7 days post-contusion (p = 0.0381).

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis of junctional proteins in bladder tissue from injured and sham animals. (A) Composite images of representative Western blots of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) (220 kDa), occludin (65 kDa), claudin-5 (22 kDa), and β-actin (42 kDa), which were identified by binding to specific antibodies. β-Actin was used as an internal control for equal loading. (B) ZO-1 expression levels were significantly decreased at 2 (p < 0.001) and 6 h (p < 0.01) after injury compared to sham controls. ZO-1 levels returned to normal levels after 24 h. (C) Occludin expression decreased significantly between the 2- and 72-h time points (p < 0.01 at each point) before returning to normal levels by 7 days post-injury. (D) A significant decrease in claudin-5 expression levels was only observed at the 7-day time point (p < 0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by a Tukey's multiple range test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.05 (n = 4/time point).

Bladder deficits in the chronic phase of SCI

Urine protein concentrations

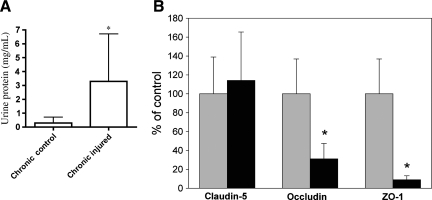

Our laboratory is focused on delineating the long-term local and systemic changes that occur as a result of SCI. As bladder care issues are prominent and a permanent issue for individuals with SCI, we decided to explore what, if any, effects of chronic SCI could be found within the bladder. We assessed overall protein levels in urine obtained from chronically-injured adult rats at 7 months post-SCI and compared them to samples obtained from uninjured, age-matched control rats. Prior to collection, chronically-injured and uninjured control subjects were treated for 7 days with a broad-spectrum antibiotic to treat any ongoing infection of the urinary tract. Urine collected from chronically-injured rats contained nearly three times the level of protein seen in urine from age-matched control animals (p = 0.0286) (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Chronic bladder deficits. (A) Protein in the urine. Urine was collected from rats 7 months after spinal contusion injury (n = 8) and age-matched control (uninjured) animals (n = 6). There was a roughly threefold increase in the amount of protein in the urine collected from chronically-injured rats compared to control animals (p = 0.0286). Student's t-test was used to compare chronically-injured and age-matched control urine samples. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. (B) Aberrant tight junction protein expression in bladders of rats with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinally-contused rats were sacrificed at 10 months post-injury and their bladders were harvested for Western blot analysis of the tight junction proteins occludin and claudin-5, and the submembranous protein zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1). Bladders from uninjured, age-matched animals served as controls. Claudin-5 levels do not appear to be significantly different when viewed as a percentage of control (n = 4 uninjured; n = 5 injured). Due to the small number of subjects, however, we interpret this result with caution. However, both occludin (n = 5 uninjured; n = 12 injured; p = 0.0114), and ZO-1 (n = 5 uninjured; n = 12 injured; p = 0.0002) exhibited substantial and significant deficits compared to age-matched controls (uninjured values indicated by gray bars, and chronically-injured values indicated by black bars). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple range test, and differences were considered significant at p < 0.01. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Tight junction protein expression in the bladders of chronically-injured rats

The observed increase in urine protein in chronically-injured subjects induced us to ascertain if the barrier properties of the uroepithelium exhibited any dysfunction. We examined bladders taken from chronically-injured rats at 10 months post-injury to determine the expression of the tight junction proteins occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1, and compared them with uninjured, age-matched control rat bladders. While the differences in claudin-5 levels between age-matched controls and chronically-injured subjects did not reach statistical significance, likely a result of the low number of subjects sampled, we observed significant reductions in both occludin (p = 0.0114) and ZO-1 (p = 0.0002) (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

Traumatic injury to the spinal cord can result in substantial dysfunction of normal bladder activity. Many of these deficits, including incontinence, lack of normal voiding control, bladder hyperactivity, and dyssynergia, result from a lack of synchronization between sensory and motor control, and can become long-term or even permanent (Tai, 2006). In addition to these complications, patients with SCI are at higher risk for bacterial cystitis, chronic bacterial infections within and under the uroepithelial layer, and bladder cancer (Hung, 2007; Pannek. 2002). These infections are often linked to the use of indwelling catheters (Hung, 2007); however, it is also possible that other pathological mechanisms may be involved. In animal models of traumatic SCI, hematuria and a breakdown of the uroepithelium lining the lumen of the bladder often occur (Apodaca et al., 2003). This breakdown is initiated early after injury, and is characterized by a loss of transepithelial resistance and enhanced permeability to both water and urea (Apodaca et al., 2003). While these changes were largely restored to normal or near normal levels by 28 days post-injury, there is a substantial period in which urine and urine contents have access to the underlying mucosal tissue. It is conceivable that invasive bacteria may gain access to the underlying tissues, where they may contribute to a chronic state of cystitis for months to years after injury. The data from the current study support and extend the previous work of Apodaca and colleagues (Apodaca et al., 2003), demonstrating a rapid failure of uroepithelial integrity following SCI. We provide additional evidence that early post-injury, hematuria is associated with a cellular inflammatory response, as evidenced by both elevated levels of MPO activity in the wall of the bladder, as well as the presence of large numbers of MPO-IR neutrophils. Loss of bladder integrity appears to be linked to a loss of tight junction proteins that normally contribute to bladder integrity (Acharya et al., 2004). Here we provide new evidence of uroepithelial dysfunction in the chronic phase of SCI. Chronically-injured rats were found to have substantially elevated levels of proteins in the urine compared with age-matched controls. Bladders from chronically-injured subjects also demonstrate significant deficits in occludin and ZO-1 expression compared to uninjured, age-matched controls. Such deficits in the chronic phase of SCI may: (1) indicate that bladder uroepithelium may never fully recovery from SCI, and (2) explain the enhanced susceptibility to cystitis and bladder cancer that is all too frequent in chronic SCI patients (Hung, 2007; Pannek, 2002).

Hematuria is commonly reported in rodent models of SCI (Apodaca et al., 2003). Hematuria is often thought to be a result of bladder infection. However, Apodaca and colleagues recently demonstrated a neurogenic component to the rapid breakdown of the rodent bladder uroepithelium, that results in a transient loss of transepithelial resistance and an increase in permeability to water and urea. Acharya and associates hypothesized that SCI induces a surge in neurotransmitter release, possibly involving catecholamines, that may influence the tight junctional network present at the level of the uroepithelial umbrella cells (Acharya et al., 2004), causing a breakdown in barrier integrity and allowing the influx of urine into the underlying bladder wall. The presence of urine beneath the uroepithelial barrier is thought to stimulate a cellular inflammatory response, further contributing to the post-SCI deterioration of the bladder uroepithelial barrier (Apodaca et al., 2003). Our current results confirm and extend the observations of Apodaca and colleagues, demonstrating that: (1) hematuria, as evidenced both by the general presence of protein, and specifically hemoglobin, occurs rapidly following spinal contusion injury, and (2) a cellular inflammatory response occurs within the uroepithelium following spinal contusion injury. Both MPO activity, as well as MPO-IR neutrophils, were detected in the bladder wall at 48 h post-SCI, and uroepithelial breakdown occurs in tandem with a loss of both tight junction proteins (claudin-5 and occludin), as well as ZO-1, a protein necessary for linking tight junction proteins to the cytoskeleton (Denker and Nigam, 1998). While it is possible that the loss of uroepithelial barrier integrity and the influx of neutrophils is a result of aberrant neural activity, it should also be noted that activated neutrophils are capable of breaking down tight junction protein interactions as they transmigrate through tissues, (Ginzberg et al., 2001) and may thus contribute to uroepithelial dysfunction.

The rapid decrease in junctional protein levels in the bladder following SCI appears to match the reduction in bladder transepithelial resistance observed by Apodaca and colleagues (Apodaca et al., 2003). Levels of the submembranous protein ZO-1 were reduced almost 10-fold by 2 h post-injury. ZO-1 serves as a linking protein, connecting tight and adherens junction proteins in the paracellular cleft with the cell's actin cytoskeleton (Denker and Nigam, 1998). Loss of ZO-1 may indicate an early dissolution of this connection, and may represent the earliest phase of breakdown in the uroepithelial junctional network. Similarly, bladder levels of occludin are also significantly, though transiently, reduced by 2 h post-injury. These deficits appear to precede the observed increases in urine proteins and hemoglobin. Occludin levels remain reduced until 72 h post-injury, but return to near-control levels by 7 days. This time point is also associated with a reduction in urine protein and hemoglobin to near-baseline levels. The role of occludin in the maintenance of uroepithelial function has not been well established. While it is possible that occludin may play a role in bladder barrier function, Schulzke and colleagues recently demonstrated that occludin plays a more important role in the regulation of epithelial cell differentiation (Schulzke et al., 2005). Interestingly, claudin-5 levels show a similar decrease, that does not become significant until 7 days post-injury. Recent studies using claudin-5-knockout mice suggest that loss of this protein does not result in an overt failure of tight junction complexes, but rather is characterized by increased permeability to smaller, lower-molecular-weight substances (Nitta et al., 2003). This, together with the loss of ZO-1 protein, appears to cause the bladder epithelium to undergo rapid structural alterations that may contribute to both the loss of transepithelial resistance, and the increase in permeability observed by Apodaca and colleagues (Apodaca et al., 2003).

Using a clinically-relevant spinal contusion model, we demonstrate that protein levels, including that of hemoglobin, are dramatically elevated within hours of injury. Urine protein levels initially rise, but taper off by 24 h post-SCI, becoming statistically insignificantly different from those of sham animals. Cystitis is a common condition associated with the chronic phase of SCI (Janzen et al., 2001). While bladder infections resulting from indwelling catheters have been thought to contribute to chronic cystitis (Vaidyanathan et al., 2002), Janzen and colleagues found no correlation between the number of bladder infections and bladder histology (Janzen et al., 2001). Thus it is conceivable that chronic cystitis may be a result of other pathological processes at work in the bladders of chronically-injured subjects. We noted the presence of higher levels of protein in the urine of chronically-injured rats compared to uninjured, age-matched control animals. Upon further analysis, we found bladder levels of both ZO-1 and occludin to be dramatically and significantly reduced compared to control animals. Interestingly, claudin-5, which has previously been shown to undergo losses in the acute stage of injury, was not statistically significantly different from control animals, suggesting that the pathological processes at work in the bladders of chronically-injured rats may target discrete components of the tight junctional network. However, it is important to note that the number of chronically-injured subjects was small, raising concerns about statistical power when assessing the differences seen in claudin-5. Occludin, as discussed above, may do more than influence barrier integrity in epithelial tissues. It may also be an important regulator of epithelial cell differentiation (Schulzke, 2005).

The barrier properties of uroepithelial tissue prevent the re-entry of urine into the system, and loss of barrier integrity during the chronic phase of injury may contribute to the pathologies associated with chronic SCI, including cystitis and fibrosis (Janzen et al., 2001), which result in substantial deficits in patient quality of life. The goal of these experiments is to formulate therapeutic options to either prevent the loss of barrier integrity in chronic SCI patients, or to strengthen and stabilize urinary bladder integrity once such deficits have taken place. While this study provides novel and important data describing alterations in the bladder seen during the acute and chronic stages post-SCI, subsequent studies are needed to determine the precise molecular mechanisms behind these pathological changes. Such studies are crucial and may provide novel new treatments that will improve the quality of life for SCI patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Bindu Nair for her technical help and assistance in this study. Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowship of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grants NINDS NS45462 and NINDS RO1 NS049409).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Acharya P. Beckel J. Ruiz W.G. Wang E. Rojas R. Birder L. Apodaca G. Distribution of the tight junction proteins ZO-1, occludin, and claudin -4, -8, and -12 in bladder epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F305–318. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00341.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca G. Kiss S. Ruiz W. Meyers S. Zeidel M. Birder L. Disruption of bladder epithelium barrier function after spinal cord injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2003;284:F966–F976. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00359.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder L.A. de Groat W.C. Mechanisms of disease: involvement of the urothelium in bladder dysfunction. Nat. Clin. Pract. Urol. 2007;4:46–54. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder L. Role of the urothelium in bladder function. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 2004:48–53. doi: 10.1080/03008880410015165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder L.A. Role of the urothelium in urinary bladder dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Prog. Brain Res. 2006;152:135–146. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)52009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks T.A. Hawkins B.T. Huber J.D. Egleton R.D. Davis T.P. Chronic inflammatory pain leads to increased blood-brain barrier permeability and tight junction protein alterations. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;289:H738–H743. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01288.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin A.C. Parkos C.A. Pathobiology of neutrophil transepithelial migration: implications in mediating epithelial injury. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2007;2:111–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craggs M.D. Balasubramaniam A.V. Chung E.A. Emmanuel A.V. Aberrant reflexes and function of the pelvic organs following spinal cord injury in man. Auton. Neurosci. 2006;126–127:355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby W.H. Furth F.W. A modification of the benzidine method for measurement of hemoglobin in plasma and urine. Blood. 1956;11:380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denker B.M. Nigam S.K. Molecular structure and assembly of the tight junction. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;274:F1–F9. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginzberg H.H. Cherapanov V. Dong Q. Cantin A. McCulloch C.A. Shannon P.T. Downey G.P. Neutrophil-mediated epithelial injury during transmigration: role of elastase. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G705–G717. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebosch C.E. Recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment of spinal cord injury. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2002;26:238–255. doi: 10.1152/advan.00039.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung E.W. Darouiche R.O. Trautner B.W. Proteus bacteriuria is associated with significant morbidity in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:616–620. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen J. Bersch U. Pietsch-Breitfeld B. Pressler H. Michel D. Bultmann B. Urinary bladder biopsies in spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:568–570. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen J. Vuong P.N. Bersch U. Michel D. Zaech G.A. Bladder tissue biopsies in spinal cord injured patients: histopathologic aspects of 61 cases. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:525–530. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1998)17:5<525::aid-nau8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta T. Hata M. Gotoh S. Seo Y. Sasaki H. Hashimoto N. Furuse M. Tsukita S. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 2003;161:653–660. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg M.D. Smith J. Marcillo A. The pathology of human spinal cord injury: defining the problems. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;21:429–440. doi: 10.1089/089771504323004575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannek J. Transitional cell carcinoma in patients with spinal cord injury: a high risk malignancy? Urology. 2002;59:240–244. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01495-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D.M. Leone A.K. Shellenberger J.J. Dudowicz K.A. King J.M. Proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma modulate epithelial barrier function in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells through mitogen activated protein kinase signaling. BMC Physiol. 2006;6:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6793-6-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson G. Cardenas D.D. Neurogenic bladder in spinal cord injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2007;18:255–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.03.005. , vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheff S.W. Rabchevsky A.G. Fugaccia I. Main J.A. Lumpp J.E., Jr. Experimental modeling of spinal cord injury: characterization of a force-defined injury device. J. Neurotrauma. 2003;20:179–193. doi: 10.1089/08977150360547099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulzke J.D. Gitter A.H. Mankertz J. Spiegel S. Seidler U. Amasheh S. Saitou M. Tsukita S. Fromm M. Epithelial transport and barrier function in occludin-deficient mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1669:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai C. Roppolo J.R. de Groat W.C. Spinal reflex control of micturition after spinal cord injury. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 2006;24:69–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toosi K.K. Nagatomi J. Chancellor M.B. Sacks M.S. The effects of long-term spinal cord injury on mechanical properties of the rat urinary bladder. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008;36:1470–1480. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9525-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan S. Mansour P. Soni B.M. Singh G. Sett P. The method of bladder drainage in spinal cord injury patients may influence the histological changes in the mucosa of neuropathic bladder—a hypothesis. BMC Urol. 2002;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizzard M.A. Alterations in growth-associated protein (GAP-43) expression in lower urinary tract pathways following chronic spinal cord injury. Somatosens. Mot. Res. 1999;16:369–381. doi: 10.1080/08990229970429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. Dawson R. Crane I.J. Liversidge J. Leukocyte diapedesis in vivo induces transient loss of tight junction protein at the blood-retina barrier. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:2487–2494. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X. Xu L. Zhang X.D. Cui F.Z. Effect of spinal cord injury on urinary bladder spinal neural pathway: a retrograde transneuronal tracing study with pseudorabies virus. Urology. 2003;62:755–759. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00486-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]