Abstract

The hormone, pancreatic polypeptide (PP) is postulated to be involved in body weight regulation. PP release is dependent on vagal activation and is a marker of vagal efferent activity. Because vagal activity plays a role in glucose homeostasis, elucidating the conditions of activation has important implications for nutrient metabolism. In humans, modified sham-feeding is known to elicit vagally-mediated hormonal responses. We present results of 3 studies in which healthy human subjects tasted various stimuli including sweet and salty liquids, unflavored and flavored gum and mixed nutrient foods flavored with either sweet or salt and rendered palatable or unpalatable. We examined the effects of these stimuli on PP levels relative to fasting. We found that liquids flavored with either glucose or salt, did not elicit an increase in PP levels greater than fasting. Similarly, chewing gum, whether unflavored or flavored with a non-nutritive sweetener or the sweetener paired with a mint flavor, did not significantly increase PP levels. In contrast, when subjects tasted mixed nutrient foods, these reliably elicited increases in PP levels at 4 min post stimulus (sweet palatable, p<0.002; sweet unpalatable, p<0.001; salty, palatable, p<0.05, salty unpalatable, p<0.05). The magnitude of release was influenced by the flavor, i.e. a sweet palatable stimulus (320.1±93.7 pg/ml/30 min) elicited the greatest increase in PP compared with a salty palatable stimulus (142.4±88.7 pg/ml/30 min; P<0.05). These data suggest that liquids and chewing gum do not provide adequate stimulation for vagal efferent activation in humans and that mixed nutrient foods are the optimal stimuli.

Keywords: vagal, cephalic phase, taste, parasympathetic, hormone, pre-absorptive hormones, sensory

Introduction

Pancreatic polypeptide (PP) is a 36 amino acid peptide produced in the Type F cells of endocrine pancreatic islets and localized to the pancreas and gastrointestinal tract [1]. PP is released during the pre-absorptive and post-prandial phases of nutrient metabolism [2]. The physiological function of PP is still largely unknown although emerging evidence suggests that the peptide may be involved in the regulation of energy balance [3]. Peripheral administration of PP inhibits food intake and stimulates energy expenditure in a dose-dependent manner in rodents [4]. Similarly, in human subjects, infusion of PP has been reported to reduce food intake when subjects were given access to a buffet meal [5;6], In patients with Prader-Willi syndrome, who typically exhibit low baseline and meal stimulated serum PP levels [7] coupled with marked hyperphagia and high body mass index, peripheral PP administration has also been shown to reduce food intake [8]

Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that PP release from the pancreas is under vagal control [2;9]. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve results in the release of acetylcholine from the nerve terminal and upon binding with muscarinic receptors elicits the release of PP [9;10]. In vitro, acetylcholine and other muscarinic agonists such as carbachol are potent stimulators of PP release from pancreatic islets [11–13]. Conversely, both vagotomy and the muscarinic antagonist atropine inhibit PP release in vivo, verifying cholinergic mediation of the peptide [2;14]. Unlike insulin which is responsive to multiple secretagogues, PP release is solely dependent on vagal efferent activation. As direct measurement of vagal activity at the pancreas is not possible due to the rapid degradation of acetylcholine in the plasma, PP responses can provide insight into the physiological conditions under which vagal efferent fibers are activated.

Understanding the conditions of vagal activation is important as emerging evidence suggests that the vagus plays a role in maintaining glucose homeostasis. Increased vagal efferent activity decreases hepatic glucose production [15] and increases insulin release [16;17], reflecting the anabolic nature of vagal activation. In addition, new studies suggest that increased vagal efferent activity and/or enhanced receptor sensitivity to acetylcholine are compensatory mechanisms that contribute to enhanced insulin release during conditions in which the pancreatic b-cell is chronically challenged [18;19]. Thus, assessing the magnitude of vagal activation by monitoring PP release may provide information on an individuals’ capacity to maintain euglycemia during physiological challenges.

In humans, one approach to investigating neurally-mediated hormonal release in the absence of the confounding effect of nutrient-induced stimulation is to utilize what is a known as a modified-sham feed. In this experimental paradigm, subjects taste, chew and then expectorate a food-related stimulus [20;21]. Vagal activation is initiated by the sensory qualities of food and stimulates the pre-absorptive release of hormones including insulin, glucagon and PP. Pre-absorptive physiological responses are termed cephalic phase reflexes referring to their neural origin, i.e. the brain. In general, cephalic phase reflexes are thought to act as preparatory responses to minimize metabolic fluctuations and optimize nutrient digestion and metabolism [22]. A prototypical example is cephalic phase insulin release (CPIR) which has been shown to contribute to glucose tolerance by enhancing post-prandial glucose disposal [23]. Previous work in our laboratory has explored the sensory conditions necessary for elicitation of vagally-mediated cephalic phase insulin and PP release in humans. We have found that in contrast to CPIR which is fragile and sensitive to inhibition, cephalic phase PP release in response to the taste of food, is robust [24]. In some individuals, increases in PP levels in response to oral sensory stimulation can occur, independent of increases in cephalic phase insulin [25]. Therefore, to explore the sensory conditions required for food-related vagal activation, we have investigated PP responses to a variety of stimuli. In the present paper, we present the results from three studies exploring the effects of oral sensory stimulation provided by 1) liquids 2) gums and 3) nutritive food on cephalic phase PP release. We have found that while liquids and gums are inadequate stimuli for vagal activation, solid, mixed nutrient foods elicit reliable PP release.

General Methods

The data presented are from three studies involving different groups of subjects each presented with different stimuli to elicit pancreatic polypeptide release. Common methodologies among studies include subject screening, method of sham-feeding, blood sampling, biochemical analysis and statistical analysis. These common methodologies are presented first, followed by a description of the subject population and the individual methods and results for each study in numerical order.

Subject Screening

All subjects were recruited through newspaper advertisements and underwent a telephone interview to assess eligibility. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had chronic illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension, abnormal heart rhythms, smoked or took any prescription medication. All studies were conducted at the Monell Chemical Senses Center where subjects had height and weight measured. In order to control for the effect of the menstrual cycle, all experimental testing in women took place within the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle (defined as ten days after the start of menses). All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and all subjects signed an informed consent form prior to participation in the study.

Sham-Feeding

Sham-feeding in which a subject tastes, chews and expectorates a food provides a means of eliciting hormonal release through vagal efferent activation, independent of nutrient absorption [21;26]. Because the magnitude of cephalic phase hormonal release is small relative to post-prandial levels and exhibits a large intra- and inter-subject variability, it is necessary to verify that the small pre-absorptive increases are greater than the normal variation and pulsatility of hormonal secretion. Therefore, a fasting condition must be incorporated into the experimental design such that hormones are measured during the same time period and with the same frequency of blood sampling as during the experimental challenge. Area under the curve (AUC) is calculated for the fasting condition and statistically compared to the AUCs during the experimental challenges. Thus, all studies have a fasted condition. In Study 1, which involved liquid stimuli, subjects were requested to taste, without swallowing, a liquid stimulus, swish the solution around in their mouth and then expectorate the solution. This procedure was repeated for a 2 minute period. In Study 2, subjects were asked to chew the gum based stimuli for a two-minute period. To control for the chewing rate, the subjects were asked to chew at the rate set by a metronome placed on the table. In Study 3, subjects were requested to sham-feed a food stimulus. Subjects were instructed to take a bite of the food, chew the food until it felt uncomfortable in their mouth and then expectorate the food. Subjects were required to repeat this procedure for a 3 minute period. Previous work in our laboratory have demonstrated that both 1 and 3 minutes of sham-feeding are adequate for eliciting a cephalic phase insulin response [27]. The length of time that subjects were exposed to the liquids and gum was shorter to replicate normal physiological conditions during drinking or chewing gum.

Blood Sampling

All studies were done in the fasted state. Subjects were instructed to fast from 10 pm the previous evening until the following morning. Subjects were encouraged to drink water to ensure hydration. To ensure that subjects were in a fasted state, blood glucose was measured using a handheld glucometer. If blood glucose was found to greater than 100 mg/dl, testing was not initiated. All blood sampling was initiated between 8 am and 10 am (start time was always consistent within each study) with placement of an arterialized venous catheter into a hand vein in a retrograde direction. The hand was warmed with a heated hand box or heating pad to allow the acquisition of arterialized venous blood. The catheter was kept patent by a slow infusion of saline. Subjects sat quietly for 30 min to acclimatize to the insertion of the catheters, prior to any study interventions or blood sampling. For studies 1–3, a minimum of two baseline blood samples were taken at various intervals prior to the food stimulus. Typically, these baseline samples were taken at -15, -5 or -1. Post-stimulus blood samples were obtained at 2,4,6,8,10,12,14, 20, 25 and 30 min with the stimuli being administered at time=0. For all studies, a 5 ml sample was collected into a vacutainer with EDTA. Trasylol and leupeptin, proteinase inhibitors were added immediately and the sample placed on ice. After each sample was obtained, the catheter was flushed with saline to keep the line patent. Samples were centrifuged and the serum aliquoted and frozen at −80 C within one hour of collection.

Biochemical Analysis

For all studies, plasma immunoreactive pancreatic polypeptide was measured in duplicate by a double-antibody radioimmunoassay using antibody purchased from ALPCO (Salem, NH: catalogue #13-RB-316). The intrassay coefficient of variation for the low concentrations of pancreatic polypeptide standard was 7.17% and 9.92% for the high concentrations. The interassay coefficient of variations for low concentrations was 32.9% and 15.6% for the high concentrations. Analysis of pancreatic polypeptide and insulin were performed by the Diabetes Research Center of the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to measurement of PP levels, plasma glucose and insulin levels were measured in all samples. No significant increases in insulin or decreases in glucose were found in the studies presented. These data are not shown in this paper

Statistical Analysis

To determine if increases in hormonal responses were significantly elevated over baseline, a repeated measures analysis of variance was used to determine if there were significant time interactions. Post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s t-test was used to determine if individual time points were significant elevated over baseline means. To determine significant differences among treatments two approaches were used: 1) repeated measures analysis of variance to determine significant time × treatment interactions and 2) repeated measures analysis of variation to determine significant differences among areas under the curves (AUC). With the latter approach, AUCS were first determined by subtracting the mean baseline value (first 2 blood samples) from the amount of hormone released at each time point. These data were then plotted and the area under the curve calculated by a point-to-point method using computer software (Origin, Northhampton, MA). All AUCs are reported for 30 min after the oral stimulus and expressed as picograms/ml/30 min. Post-hoc testing using either Tukey’s or in the case of Study 3, Dunnet’s test was used to determine differences among treatments and the control, respectively. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Study 1 Pancreatic polypeptide responses to tasting sweet and salty solutions

The objective of study 1 was to determine if sweetened or salty liquids could elicit vagal efferent activity as reflected by increases in PP levels. Neurally-mediated insulin release in response to sweet flavored liquids has consistently been demonstrated in animals [28] but our laboratory has not previously observed similar responses to sweet liquids in humans [27;29]. Since the magnitude of PP response to oral sensory stimuli is greater than the cephalic phase insulin response, we considered that PP release may be a more sensitive indicator of vagal activation to taste stimuli.

Subjects and Methods

Ten subjects participated in this study (5 male, 5 female) with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 22.9±1.3 (range=21–25) and age of 22.3 (19–30). Each subject underwent 3 experimental conditions: 1) fasting 2) tasting a sweet glucose solution 3) tasting a salty solution. The sweet solution was a 0.9 M glucose solution formulated by adding 81g of glucose to 500ml of double distilled water. The salty solution was made by adding 11.65 g of sodium chloride to 500 ml of double distilled water to obtain a 0.4M NaCl solution

Sweet and Salty Solutions: Results

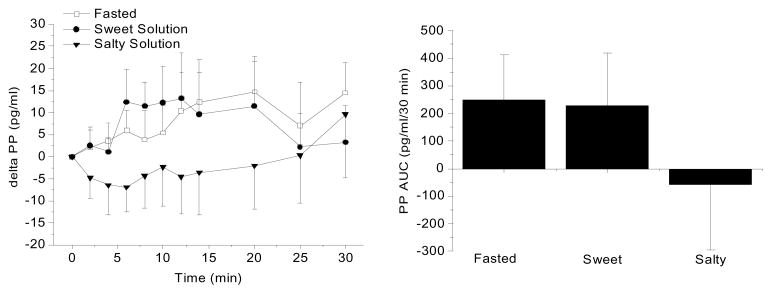

Figure 1 illustrates mean PP levels expressed as a difference from baseline following oral sensory stimulation by sweet and salty solutions and compared to fasting PP levels during the same time period. Baseline levels of PP were comparable among the three conditions (66.3 pg/ml, fasting; 53.6 pg/ml, sweet solution condition, 59.8 pg/ml salty solution condition). Figure 1 (left) illustrates the mean PP levels (± standard error). No significant differences among the treatments were found. Area under the curve for the three experimental conditions were: 248 ± 513 pg/ml/30 min, fasted; 224 ± 603 pg/ml/30 min, sweet liquid, −54 ± 748 pg/ml/30 min salty liquid (Figure 1, right graph). Neither the sweet solution nor the salt solution elicited changes in PP levels significantly different from fasting. While the taste of the salty solution appeared to suppress PP release, this may be a reflection of the normal variation in PP response as there was no statistical significance between the salty condition and fasting. The sweet solution was rated as less intense (1.3±0.71) and with greater hedonic value (6.3±1.8) compared to the salty solution (6.9±0.31, intensity and 2.4±2.0, liking).

Figure 1.

Left graph: Mean PP levels during fasting and in response to the taste of sweet and salty liquids in normal weight men and women (n=10, mean ± standard error). Right graph: PP area under curve (AUC) over a 30 min period for the three experimental conditions. No significant differences were found among treatments.

Study 2: Pancreatic polypeptide responses to unflavored and flavored chewing gums

The lack of PP release to the taste of a sweet liquid confirmed our previous findings that sweetened solutions are inadequate stimuli for activation of vagally-mediated hormonal release. Studies conducted on other vagally-mediated responses such as gastric acid release suggested that increasing the sensory components provided by the food stimuli increased the magnitude of response [30]. For example, while visual and olfactory stimulation could elicit gastric acid release, the magnitude of release was much greater with the added sensory stimulation provided by taste. We reasoned that liquids did not provide adequate sensory stimulation for elicitation of the pre-absorptive responses through vagal activation and that chewing was a required stimulus. Therefore, in Study 2, we tested the effect of chewing flavored and unflavored gum.

Subjects and Methods

Fifteen subjects participated in this study (11 male, 4 female) with a mean BMI of 22.4±1.9 (range=19–25) and mean age of 24.2 (21–28). Each subject underwent 4 experimental conditions: 1) fasting 2) chewing an unflavored, unsweetened gum base 3) chewing a gum base sweetened with a non-nutritive sweetener and 4) chewing a gum base flavored with mint and sweetened with a non-nutritive sweetener. Experimental conditions were administered in a randomized order. As described above, subjects chewed the gum at a regulated pace for a 2 minute period. The gums were formulated and donated by Wm. Wrigley Jr. Co.

Results: Pancreatic polypeptide response to chewing gum

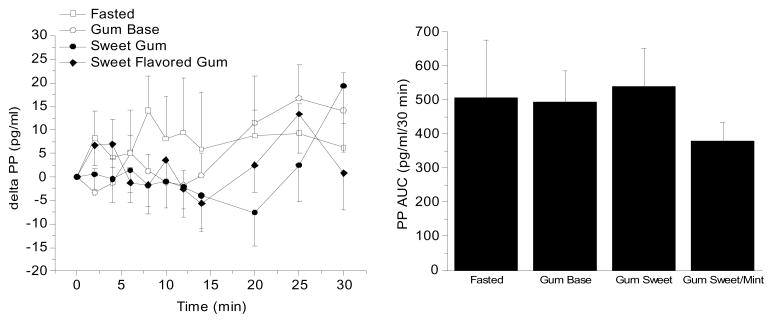

Figure 2 (left) illustrates the mean PP levels (± s.e.) expressed as a difference from baseline to 4 different conditions: 1) fasting, 2) chewing gum base with no sweetness or flavor, 3) chewing sweetened gum and 4) chewing sweet gum with a mint flavor. No significant differences in fasted baseline levels of PP were found among the four conditions (64.1 pg/ml, fasting; 60.0 pg/ml, gum base condition, 63.2 pg/ml sweetened gum base and 67.0 pg/ml, sweetened gum with mint flavor. Chewing gum was not found to significantly increase PP levels as compared to baseline fluctuation (mean AUC fasting: 244.8±676.5 pg/ml/30 min) whether the stimulus was the gum base alone (178.4±376 pg/ml/30 min), sweetened gum (147.6±595.9 pg/ml/30 min) or sweetened and having a flavor (167.5±296.8 pg/ml/30 min).

Figure 2.

Left graph: Mean PP levels during fasting and in response to chewing an unflavored gum, sweet gum flavored with a non-nutritive stimulus and sweet gum flavored with mint (n=15, mean ± standard error). Right graph: PP area under curve (AUC) over a 30 min period for the four experimental conditions. . No significant differences were found among treatments.

Study 3: Pancreatic polypeptide response to sham-feeding palatable and unpalatable sweet and salty foods

Based on previous reports, mixed nutrient meals are known to be effective stimuli for eliciting PP release [2]. Studies conducted in our laboratory also indicated that mixed nutrient, fat containing stimuli were optimal for eliciting PP release by sham-feeding [25]. The objective of this study was to determine if, within the context of a mixed nutrient stimulus in which the base texture and nutrient content were controlled, palatability could influence the magnitude of vagal efferent activation and subsequently PP release. We hypothesized that during sham feeding, pancreatic polypeptide would be greater in response to foods perceived as palatable. We were also interested in pursuing differences in PP responsivity to sweet and salty flavored foods since a trend towards a suppression was observed following the taste of a salty solution.

Subjects and Methods

A total of 12 subjects participated in this study (6 men, 6 women) with a mean BMI of 22.9 Kg/M2 (range 20–25) and mean age of 28.2±6.7 (range 21–45). Following a telephone screening and informed consent, each subject participated in a pre-test in which they were asked to rate the four stimuli for hedonic value on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0–9 asking the question; how much do you like this food? Subjects had to show difference of 4 units between like and dislike for palatable and unpalatable stimuli in order to participate in the study. Upon acceptance into the study, each subject underwent 5 experimental conditions in a randomized fashion: 1) fasted 2) sham-feed palatable sweet food, 3) sham-feed unpalatable sweet food, 4) sham-feed salty palatable food and 5) sham-feed salty unpalatable foods.

The food vehicle was cream cheese on a wheat cracker with varying levels of sweetener or salt. Foods were made unpalatable by the addition of high levels of sweetener (aspartame) or salt. All stimuli were composed of 30 gram of cream cheese to which was added 1 gram of aspartame for the palatable sweet stimulus, 20 g of aspartame for the unpalatable sweet stimulus, 0.4 gram of salt for the palatable salty stimulus and 6 g of salt for the unpalatable salty stimulus. All stimuli had fat content ranging from 19.2% – 22.1% fat, carbohydrate content ranging from 63.3–86% and protein content ranging from 2.6–4.7%. Subjects sham-feed the stimuli as described above.

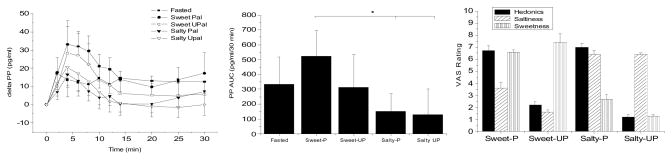

Results: Pancreatic Polypeptide Responses to the Taste of Mixed Nutrient Food

Mean baseline PP levels were not statistically different between the 5 experimental conditions (48.0±21.8 pg/m, fasting; 45.9±18.8 pg/ml, sweet palatable; 47.5±26 pg/ml, sweet unpalatable; 51.9±26.5 pg/ml, salty palatable; 55.7±21.5 pg/ml, salty unpalatable). Figure 4A illustrates PP levels (mean± s.e.) during the fasting and sham-feeding conditions represented as a difference from baseline. All four stimuli resulted in a characteristic cephalic phase response with an increase in PP levels starting at 2 minutes post-oral stimulation, peaking at 4 min and returning to baseline around 20 min post-stimulus. The fasted condition resulted in a small rise but did not result in the defined peak. Furthermore, using repeated measures ANOVA to determine time effects and Tukey’s for post-hoc analysis, none of the points during the fasting condition were significantly different from the mean baseline. In contrast, for all 4 of the experimental conditions providing oral sensory stimulation with a nutritive stimulus, significant time effects were found (sweet palatable, p<0.002; sweet unpalatable, p<0.001; salty, palatable, p<0.05, salty unpalatable, p<0.05). Significant increases in post-stimulus PP levels were found at the 4 min time point as compared to mean baseline levels for the 4 conditions. For the sweet palatable stimulus, significant increases in PP levels were also observed at 6 and 8 minutes post-stimulus and for the sweet unpalatable stimulus, the 6 min post-stimulus time point was also significantly elevated compared to baseline. The 30 min AUCS for the 5 conditions were: 356.6±627 pg/ml/30 min, fasted; 525.1±590.4 pg/ml/30 min, sweet palatable; 314.2±755.7 pg/ml/30 min, sweet unpalatable; 150.2±414.9 pg/ml/30 min, salty palatable and 131.9±596 pg/ml/30 min, salty unpalatable (Figure 4B). Statistical planned comparison of the AUCs for PP release revealed a significant treatment effect (F=2.9, P<0.05) but post-hoc analysis revealed that the only significant difference was between the sweetened palatable stimulus compared with the salty palatable stimulus. These data suggest that in the context of solid food, similar to that observed with the liquids, salty flavor tends to repress vagal efferent activity and consequently PP levels. While there was a trend towards a decrease in PP levels following the unpalatable sweet stimulus, the AUC was not significantly different than the AUC after sweet palatable stimulus and not significantly different from fasting. We also calculated the AUC for just the traditional cephalic phase period (first 10 min) and found similar results (AUCs for 10 min: 176.0±86.7 pg/ml/10 min, fasted; 320.12±93.7 pg/ml/10 min, sweet palatable; 229.9±126 pg/ml/10 min, sweet unpalatable; 110.3±60.4 pg/ml/10 min, salty palatable; 142.4±88.7 pg/ml/10 min, salty unpalatable). Ideally, the sweet and salty flavors should have been compared to a cream cheese stimulus without flavor to definitively determine the effect of flavor compared to a base stimulus as was done in the gum study. However, we felt that adding an additional condition was not feasible and in fact, we feel that the multiple conditions contributed to large variability observed in this study. Figure 4C illustrates the hedonic and flavor ratings to the 4 stimuli.

Discussion

Increases in circulating levels of PP are dependent on activation of vagal efferent fibers and provide a window into the magnitude of vagal efferent activity at the site of the pancreatic islet. Emerging data provides evidence for an important role of vagal activity in the regulation of insulin release [16;17;19] and hepatic glucose production [31–33] and therefore, understanding the conditions under which the vagus is activated is critical in elucidating how blood glucose is regulated under physiological conditions. In the studies presented, we progressively increased the sensory components provided by food-related stimuli to ascertain the required stimuli for activation of vagally-mediated PP release. The challenges ranged from liquid stimuli to nutritive food.

In animals, tasting sweet solutions, independent of nutrient content [28;29] elicits the release of pre-absorptive cephalic phase hormones, particularly CPIR. Earlier work in our laboratory suggested that humans may respond differently as we (and others) did not find significant increases in cephalic phase insulin after subjects tasted a variety of sweet solutions including sucrose, aspartame and saccharine [27;34]. Since pre-absorptive PP release to the taste of food is more robust and of greater magnitude than cephalic phase insulin release [35], we examined the effects of sweet (glucose) and salty solutions on pancreatic polypeptide release, two tastes which have been shown to effectively elicit cephalic phase insulin release in rats. As shown in Figure 1, no significant increase in PP levels as compared to fasting was observed in response to the sweet solution, confirming our earlier study demonstrating that the taste of sweet liquids does not stimulate vagal efferent activity in humans. The results suggest that greater oral sensory stimulation may be required to activate the vagal efferent pathway in humans and/or that neurally-mediated hormonal release may be more tightly regulated.

The lack of significant increases in either cephalic phase insulin or pancreatic polypeptide levels in response to liquid stimuli suggested that in humans, chewing may be a required stimulus for vagal activation. To address this question, we examined the effect of chewing a non-nutritive stimulus, gum. We varied the presence of sweet taste and flavor by adding first a non-nutritive sweetener and then mint flavor, a flavor commonly found in commercial chewing gum. Based on previously published work on other vagally-mediated responses such as gastric acid secretion, we had expected that as we increased the sensory stimuli provided by the stimulus, that the magnitude of PP release would increase as well. Surprisingly, we found no significant increases in PP levels after subject’s chewed sweetened or even sweetened flavored gum. However, many studies, particularly in animals, provide evidence that the cephalic phase responses are learned reflexes occurring with repeated exposure to food stimuli with the objective of optimizing nutrient digestion and metabolism [36;37]. In humans, demonstration of a learned component to these vagally-mediated responses is difficult since by the time an individual reaches adulthood, there are few foods, particularly those associated with sweet taste that would not have been associated with a post-ingestive metabolic effect. Gum, on the other hand, even sugar-containing gum, would not provide a substantial number of calories to warrant learned preparatory responses. While these data would suggest that chewing alone is not an adequate stimulus for vagal activation, it is also possible that the cephalic phase reflexes which would typically occur in response to chewing a sweet, flavored stimulus have been extinguished due to the individuals’ previous experience of chewing gum that is not associated with a caloric load. Thus, what we may be observing is a learned lack of vagal activation.

Having determined that neither sweet taste in a liquid form, nor sweet taste in the context of gum were adequate stimuli for eliciting vagally-mediated PP response, we returned back to a nutritive stimulus containing fat, in which we manipulated the flavor (sweet and salty) as well as the palatability. We found that the taste of a sweet palatable stimulus elicited a significant increase in PP and that this response was attenuated by making the same stimulus unpalatable. However, the difference was not significantly different due to the large variability observed in this study. Significant differences were found, however, between PP responses to the sweet palatable stimulus and the salty palatable stimulus. It appears that in the context of both liquids and solids, salty flavor tends to suppress vagally-mediated PP release. However, with regards to the effect of the salty solution, it is possible that hedonics played a role, since the salty solution was less “liked” than the sweet solution.

Two factors limit our ability to decisively determine the effect of palatability. The first is the lack of what could be considered an appropriate control condition, a nutritive stimulus with no flavor (i.e. cream cheese and a cracker alone). Ideally, we should have compared the sweet palatable stimulus to an unsweetened control condition. However, we felt that it was unlikely that the addition of sweet taste alone would significantly increase the palatability of the cream cheese on cracker, which would already have a high hedonic value. In addition, we were concerned that 6 experimental conditions would render the conduction of the study unwieldy. In fact, we think that the large number of experimental conditions (n=5) was responsible for the large variability in PP responses observed in this study and believe that the large variability contributed to a lack of significance between the palatable and unpalatable sweet condition. Large inter-individual differences are frequently observed in vagally-mediated responses and it is possible that the individual’s hedonic experience to the food stimuli may ultimately influence the magnitude of vagal activity and contribute to the variability. Alternatively, palatability may not play an important role in the elicitation of vagal activation. Our previous study investigating the effect of palatability on cephalic phase insulin release demonstrated no significant influence of hedonics [38]. Cephalic phase responses may be innate or learning and conditioning may play a primary role.

Taken together, these results suggest that neither tasting liquids nor chewing gum is an adequate stimulus for vagal activation. Oral sensory stimulation by mixed nutrient foods appears to reliably activate vagal efferent activity and subsequently, the elicitation of pancreatic polypeptide release. The role of palatability still needs to be clarified but these data suggest that an individual’s perception of the hedonic value of a food may influence vagally-mediated responses. Understanding the food-related conditions under which vagal activation occurs is important for predicting how ingested nutrients will be metabolized and for understanding the mechanisms by which nutrient storage and utilization takes place. Further research needs to be conducted to elucidate the relationship between an individuals’ previous experience with food and food flavors and how learning influences the metabolic consequences of nutrient ingestion.

Figure 3.

Panel A: Mean PP levels during fasting and during sham-feeding of 4 mixed macronutrient stimuli rated as: 1) sweet palatable 2) sweet unpalatable, 3) salty palatable and 4) salty, unpalatable in normal weight mean and women (n=12, mean ± standard error). Time points significantly elevated over baseline are indicated by “*”. Panel B: PP area under curve (AUC) over a 30 min period for the five experimental conditions. The PP AUC in response to the sweet palatable mixed nutrient stimulus was significantly greater than salty palatable and salty unpalatable (P<0.05). No significant difference was found between the sweet palatable and sweet unpalatable food. P<0.05 indicated by *. Panel C: Ratings of liking, salty intensity and sweet intensity of the four stimuli.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Dr. Heather Collins at the Diabetes Research Center of the University of Pennsylvania and Huong-lan Nguyen at the Monell Chemical Senses Center. We would also like to thank Wrigley Co. for the formulation of the gums used in Study 2. This work was supported by NIH grants; DK58003-07 (K.T.), Monell Chemical Senses Center and the radioimmunoassay core of DK-19525 to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errorsmaybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Katsuura G, Asakawa A, Inui A. Roles of pancreatic polypeptide in regulation of food intake. Peptides. 2002;23:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(01)00604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz TW. Pancreatic polypeptide: a hormone under vagal control. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:1411–1425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Batterham RL, Le Roux CW, Cohen MA, Oark AJ, Ellis EM, Patterson M, Frost GS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Pancreatic polypeptide reduces appetite and food intake in humans. J C E M. 2003;88:3989–3992. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kojima S, Ueno N, Asakawa A, Sagiyama K, Naruo T, Mizuno S, Inui A. A role for pancreatic polypeptide in feeding and body weight regulation. Peptides. 2007;28:459–463. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asakawa A, Inui A, Yuzuriha H, Ueno N, Katsuura G, Fujimiya M, Fujino MA, Niijima A, Meguid MM, Kasuga M. Characterization of the effects of pancreatic polypeptide in the regulation of energy balance. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1325–1336. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batterham RL, Le Roux CW, Cohen MA, Park AJ, Ellis SM, Patterson M, Frost GS, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR. Pancreatic polypeptide reduces appetite and food intake in humans. J Clin Endo Metab. 2003;88:3989–3992. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zipf WB, O’Dorisio TM, Cataland S, Sotos J. Blunted pancreatic polypeptide responses in children with obesity of Prader-Willi syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1981;52:1264–1266. doi: 10.1210/jcem-52-6-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zipf WB, O’Dorisio TM, Berntson GG. Short-term infusion of pancreatic polypeptide: effect on children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:162–166. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz T, Holst J, Fahrenkrug J, Jensen S, Nielsen O, Rehfeld J, Schaffalitzky O. Vagal, cholinergic regulation of pancreatic polypeptide secretion. JClin Invest. 1978;61:781–789. doi: 10.1172/JCI108992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanikawa M, Hayakawa T, Kondo T, Naruse S, Shibata T, Kitagawa M. Regulation of pancreatic polypeptide release is mediated through M3 Muscarinic receptors. Digestion. 1994;55:374–379. doi: 10.1159/000201168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adrian TE, Bloom SR, Hermansen K, Iversen J. Pancreatic polypeptide, glucagon and insulin secretion from the isolated perfused canine pancreas. Diabetologia. 1978;14:413–417. doi: 10.1007/BF01228136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gingerich RL, Scharp DW, Greider MH, Dye ES, Mousel KA. A new in vitro model for studies of pancreatic polypeptide secretion and biochemistry. Regul Pept. 1982;5:13–25. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(82)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamazaki H, Philbrick W, Zawalich K, Zawalich W. Acute and chronic effects of glucose and carbachol on insulin secretion and phospholipase C activation: studies with diazoxide and atropine. Am J Physiol. 2006;290:E26–E33. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00149.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teff KL, Townsend RR. Early phase insulin infusion and muscarinic blockade in obese and lean subjects. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R198–R208. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.1.R198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pocai A, Lam T, Gutierrez-Juarez R, Obici S, Schwartz G, Bryan J, Aguilar-Bryan L, Rossetti L. Hypothalamic K(ATP) channels control hepatic glucose production. Nature. 2005;434:1026–1031. doi: 10.1038/nature03439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zawalich WS, Zawalich KC, Rasmussen H. Cholinergic agonists prime the B-cell to glucose stimulation. Endocrinology. 1989;125:2400–2406. doi: 10.1210/endo-125-5-2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Alessio DA, Kieffer TJ, Taborsky GJHPJ. Activation of the parasympathetic nervous system is necessary for normal meal-induced insulin secretion in rhesus macaques. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1253–1259. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doliba NM, Qin W, Vatamaniuk MZ, Li C, Zelent D, Najafi H, Buettger CW, Collins HW, Carr RD, Magnuson MA, Matschinsky FM. Restitution of defective glucose-stimulated insulin release of sulfonylurea type 1 receptor knockout mice by acetylcholine. Am J Physiol. 2004;286:E834–E843. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00292.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teff KL, Townsend RR. Prolonged mild hyperglycemia induces vagally mediated compensatory increase in C-peptide secretion in humans. J Clin Endo Metab. 2004;89:5606–5613. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-032094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teff KL, Levin BL, Engelman K. Oral sensory stimulation in men: effects on insulin, C-peptide, and catecholamines. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:R1223–R1230. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.6.R1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teff KL, Mattes RD, Engelman K. Cephalic phase insulin release in normal weight males: verification and reliability. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:E430–E436. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.4.E430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods SC. The eating paradox:how we tolerate food. Psychol Rev. 1991;98:488–505. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.98.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teff KL, Engelman K. Oral sensory stimulation improves glucose tolerance: effects on post-prandial glucose, insulin, C-peptide and glucagon. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R1371–R1379. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.6.R1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teff K. Nutritional Implications of the Cephalic Phase Reflexes. Appetite. 2000;34:206–213. doi: 10.1006/appe.1999.0282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crystal SR, Teff KL. Tasting fat: cephalic phase hormonal responses and food intake in restrained and unrestrained eaters. Physiol Behav. 2006;89:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz T, Stenquist B, Olbe L. Cephalic phase of pancreatic-polypeptide secretion studied by sham feeding in man. Scand J Gastroent. 1979;14:313–320. doi: 10.3109/00365527909179889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teff KL, Devine J, Engelman K. Sweet taste: effect on cephalic phase insulin release in men. Physiol Behav. 1995;57:1089–1095. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00373-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grill HJ, Berridge KC, Ganster DJ. Oral glucose is the prime elicitor of preabsorptive insulin secretion. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:R88–R95. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.1.R88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berthoud HR, Jeanrenaud B. Sham feeding-induced cephalic phase insulin release in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:E280–E285. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1982.242.4.E280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman M, Richardson CT. Role of thought, sight, smell, and taste of food in the cephalic phase of gastric acid secretion in humans. Gastroenterology. 1986;90:428–433. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90943-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherrington AD, Marshall BA, Moore MC, Pagliosotti MJ, Shiota M. A role for the autonomic nervous system in regulation of glucose uptake by the liver. In: Shimazu T, editor. Liver Innervation. London: John Libber & Co. Ltd; 1996. pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pocai A, Obici S, Schwartz GJ, Rossetti L. A brain-liver circuit regulates glucose homeostasis. Cell Metabolism. 2005;1:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyle P, Liggett S, Shah S, Cryer P. Direct muscarinic cholinergic inhibition of hepatic glucose production in humans. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:445–449. doi: 10.1172/JCI113617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruce DG, Storlien LH, Furler SM, Chisholm DJ. Cephalic phase metabolic responses in normal weight adults. Metabolism. 1987;36:721–725. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(87)90106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor IL, Feldman M. Effect of cephalic-vagal stimulation on insulin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide, and pancreatic polypeptide release in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:1114–1117. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-6-1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods SC, Vasselli JR, Kaestner E, Szakmary GA, Milburn P, Vitiello MV. Conditioned insulin secretion and meal feeding in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:128–133. doi: 10.1037/h0077307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woods SC, Kulkosky PJ. Classically conditioned changes of blood glucose level. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1976;38:201–219. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197605000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teff KL, Engelman K. Palatability and dietary restraint: effect on cephalic phase insulin release in woman. Physiology & Behavior. 1996;60:567–573. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(96)80033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]