Abstract

Purpose

This multicenter, randomized, open-label study evaluated the efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of a single subcutaneous pegfilgrastim injection with daily subcutaneous filgrastim administration in pediatric patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy for sarcoma.

Patients and Methods

Forty-four patients with previously untreated, biopsy-proven sarcoma stratified into three age groups (0-5, 6-11, and 12-21 years) were randomly assigned in a 6:1 randomization ratio to receive a single pegfilgrastim dose of 100 μg/kg (n = 38) or daily filgrastim doses of 5 μg/kg (n = 6) after chemotherapy (cycles 1 and 3: vincristine-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide; cycles 2 and 4: ifosfamide-etoposide). The duration of grade 4 neutropenia, time to neutrophil recovery, incidence of febrile neutropenia, and adverse events were recorded.

Results

Pegfilgrastim and filgrastim were similar for all efficacy and safety end points, and their pharmacokinetic profiles were consistent with those in adults. Younger children experienced more protracted neutropenia and had higher median pegfilgrastim exposure than older children.

Conclusion

A single dose of pegfilgrastim at 100 μg/kg administered once per chemotherapy cycle is comparable to daily injections of filgrastim at 5 μg/kg for pediatric sarcoma patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

Dose-intensive chemotherapy has become routine for the treatment of most pediatric sarcomas because chemotherapy dose-intensity correlates with tumor response and outcome.1–3 Neutropenia is a common toxicity of these regimens.4–6 Both the depth of the neutrophil nadir and duration of severe neutropenia influence the development of infectious complications.7,8 Therefore, preventing or shortening the duration of neutropenia following chemotherapy may facilitate dose-intensity, improve safety, and control costs.

Filgrastim (r-metHu G-CSF) stimulates proliferation and maturation of neutrophil precursors9,10 and shortens the duration of neutropenia8,11,12 and its associated complications.8,12–15 Its use has become routine after chemotherapy for pediatric sarcomas5,6 and has permitted chemotherapy dose intensification via interval compression in pediatric sarcoma patients.16

A significant impediment to administering filgrastim after chemotherapy is its daily administration schedule, typically for approximately 10 days.17 In pediatric patients, filgrastim administration can be problematic. Even if parents learn to administer the injections themselves, doing so in young children often requires two caregivers and may result in psychological effects for parents and quality of life impairment of young cancer patients, although this has not been well studied.

Pegfilgrastim comprises filgrastim bound to a 20-kDa polyethylene glycol molecule. Pegylation decreases renal clearance and extends circulation half-life, resulting in sustained drug activity.18–20 Pegfilgrastim clearance is predominantly mediated by neutrophils, so the drug concentration is sustained in the circulation during chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and rapidly eliminated on neutrophil recovery.21,22 In adults, a single dose of pegfilgrastim (either 100 μg/kg or 6 mg) after chemotherapy has demonstrated safety and efficacy similar to daily filgrastim17,23; the recommended adult dosage is 6 mg administered subcutaneously once per chemotherapy cycle. A limited number of studies have evaluated pegfilgrastim dosing in pediatric patients.24–29 This phase II study was designed to evaluate the safety, clinical response, and pharmacokinetics of pegfilgrastim in pediatric patients with sarcoma receiving dose-intensive vincristine-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide/ifosfamide-etoposide (VDC/IE) chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Population

This study was approved by the institutional review board of participating centers. All patients or their legal guardian gave written informed consent before study entry. Authors had access to study data for interpretation of study results. Patient eligibility criteria (Appendix Table A1, online only) included newly diagnosed sarcoma, age younger than 22 years, and no bone marrow involvement by tumor.

Study Design

This multicenter, open-label, randomized study was initiated in 2000 and was subsequently included as part of pegfilgrastim's postmarketing commitments. It evaluated the safety, clinical response, and pharmacokinetics of a single pegfilgrastim injection in a 6:1 randomization ratio with daily filgrastim injections until neutrophil recovery in previously untreated patients with biopsy-proven sarcoma receiving four cycles of chemotherapy. The CONSORT diagram and study design are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA) supplied pegfilgrastim and filgrastim. Pegfilgrastim dosage of 100 μg/kg was chosen on the basis of efficacy and safety data in adults.22,30,31 Because of the wide range of ages and body weights in the pediatric population, weight-based dosing (100 μg/kg) for pegfilgrastim was used. Safety of the weight-based dosage was evaluated in the first three patients enrolled. After documenting an acceptable safety profile in these patients, additional patients were randomly assigned (six to pegfilgrastim, one to filgrastim), and treatment arms were divided into three age strata (0-5, 6-11, and 12-21 years).

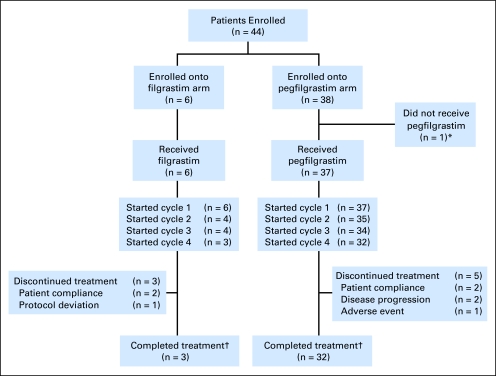

Fig 1.

CONSORT diagram. (*) One patient was withdrawn before study drug administration because of concerns about protocol-required blood draws after migration and infiltration of the patient's intravenous catheter. (†) Treatment completion was defined as completing all planned cycles of study drug.

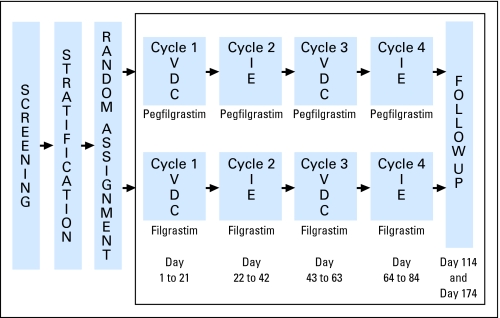

Fig 2.

Study schema. Chemotherapy: Vincristine-doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide (VDC) cycles 1 and 3 (vincristine [V] at 2.0 mg/m2 by intravenous [IV] push, days 1, 8, and 15; doxorubicin [D] at 75 mg/m2, IV infusion over 48 hours, day 1; cyclophosphamide [C] 1,200 mg/m2/d, days 1 and 2, IV infusion over 1 hour; and mesna at 360 mg/m2 in four doses by continuous infusion or bolus at regular intervals). Ifosfamide-etoposide (IE) cycles 2 and 4 (ifosfamide [I] at 1,800 mg/m2/d × 5 days, IV over 1 hour; etoposide [E] at 100 mg/m2/d × 5 days, IV over 1 hour; and mesna at 360 mg/m2 in four doses by continuous infusion or bolus at regular intervals). Growth factor: pegfilgrastim at 100 μg/kg subcutaneously [SC] by single injection 24 hours after completion of chemotherapy; filgrastim at 5 μg/kg/d SC daily 24 hours after completion of chemotherapy per package insert until absolute neutrophil count [ANC] recovery (ANC ≥ 10 × 109/L) or 24 hours before the next cycle.

Patients randomly assigned to the filgrastim group received 5 μg/kg filgrastim subcutaneously daily beginning approximately 24 hours after chemotherapy completion in week 1 (generally, day 4 in cycles 1 and 3 and day 6 in cycles 2 and 4) and continuing either until a postnadir absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of ≥ 10 × 109/L was achieved or until 24 hours before the next scheduled chemotherapy cycle, whichever occurred first. Patients randomly assigned to pegfilgrastim received 100 μg/kg subcutaneously approximately 24 hours after chemotherapy completion. Dose escalation of pegfilgrastim was to be considered for an age stratum if more than one of the six patients failed to achieve ANC recovery (ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109/L) in cycle 1. An age stratum was closed to accrual after two successive groups of six patients (within the age stratum) achieved ANC recovery. Thus, a minimum of 42 patients (12 pegfilgrastim and two filgrastim in each of the three age strata) were required to complete study-specified enrollment.

Therapy Guidelines

Four cycles of chemotherapy were administered at 3-week intervals. Mesna was used during all cycles for prevention of hemorrhagic cystitis. An ANC ≥ 1 × 109/L and a platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L were required to start each cycle. Chemotherapy doses were modified for infection only if the episode required intensive care support or was associated with typhlitis, meningitis, or pneumonia with oxygen dependence.

Laboratory Monitoring

In cycles 1 and 3, weekly chemistry panels and daily complete blood counts (CBCs) were performed until the ANC exceeded 0.5 × 109/L on two consecutive measurements. In cycles 2 and 4, both chemistry panels and CBCs were performed weekly. A CBC sample was also obtained 1 and 3 months after completion of cycle 4 laboratory monitoring. Serum samples for antibody testing were obtained before initiation of chemotherapy, at the end of treatment, and at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits. A surface plasmon resonance Biacore 3000 (Biacore, Piscataway, NJ) affinity assay was used to quantify antibodies capable of binding to filgrastim and pegfilgrastim. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. All samples positive for binding antibodies were tested for neutralizing antibodies using a cell-based neutralizing antibody assay. Pharmacokinetic samples were collected in cycles 1 and 3 before injection and 1, 2, and 4 hours after injection of pegfilgrastim or the first dose of filgrastim, and daily concurrently with CBC sample collections.

Statistical Analysis

This study was conducted to assess and provide preliminary comparison of the pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, and safety profiles of a single dose of pegfilgrastim and daily doses of filgrastim in pediatric sarcoma patients. The calculations for sample size were based on an assumption of normally distributed durations of neutropenia, as previously documented in other studies.13,30 The primary efficacy end point was the duration of grade 4 neutropenia (ANC < 0.5 × 109/L) during cycles 1 and 3. The minimum sample size (36 pegfilgrastim-treated and six filgrastim-treated patients) would allow the difference in duration of grade 4 neutropenia between the two treatment groups to be estimated with a distance from the estimate to the 95% confidence bounds of 1.3 days (assuming a standard deviation of 1.5 days) for cycles 1 and 3. Time to ANC recovery to ≥ 0.5 × 109/L in cycles 1 and 3 and rate of febrile neutropenia (FN; defined as ANC < 0.5 × 109/L and an oral or oral-equivalent temperature ≥ 38.2°C on the same day) were also assessed. Safety was evaluated across all four chemotherapy cycles.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the duration of grade 4 neutropenia, time to ANC recovery, proportion of patients without ANC recovery by day 21, and proportion of patients with FN in cycles 1 and 3 for each age cohort. For patients who did not experience grade 4 neutropenia in a given cycle, duration of neutropenia was assigned a value of 0. Adverse events (AEs) were coded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, Version 9.0) and were summarized by grade, relationship to study drugs, and treatment group.

Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated on the basis of individual serum concentration data using WinNonlin Professional (Pharsight, Mountain View, CA) software. The maximum concentration (Cmax) and the time it occurred (tmax) following dosing were recorded. A log-linear trapezoidal method was used to estimate the area under the (concentration-time) curve (AUC). AUC0-last was calculated from time zero to the time of the last measurable concentration (Ct). The first-order terminal rate constant (kel) was estimated via linear regression of the terminal log-linear delay phase. Terminal half-life (T1/2) was calculated as ln(2)/kel. AUC0-∞was estimated as the sum of corresponding AUC0-last and Ct/kel values.

RESULTS

Patients

This study was conducted between 2000 and 2007. Ten centers in the United States and Australia enrolled 44 patients, with 38 patients randomly assigned to pegfilgrastim and six randomly assigned to filgrastim. Table 1 shows baseline demographic and disease features of the study population. The median age, age distribution, race/ethnicity, weight, baseline ANC, and baseline platelet counts were similar in patients enrolled in the two treatment arms. This trial was initiated before the International Conference on Harmonisation guideline requiring a separate age stratum for children 0 to 2 years of age was developed32; therefore, results are presented by protocol-specified age strata. Four patients between the ages of 28 days and 23 months were enrolled in the study.

Table 1.

Patients' Baseline Demographic and Disease Characteristics

| Characteristic | Filgrastim (n = 6) |

Pegfilgrastim (n = 38) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 4 | 67 | 12 | 32 |

| Male | 2 | 33 | 26 | 68 |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 11.0 | 10.5 | ||

| Range | 4.0-18.0 | 0.67-21.0 | ||

| Age group, years | ||||

| 0-5 | 1 | 17 | 12 | 32 |

| 6-11 | 2 | 33 | 10 | 26 |

| 12-21 | 3 | 50 | 16 | 42 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 5 | 83 | 30 | 79 |

| Black | 0 | 3 | 8 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 17 | 4 | 11 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| Disease | ||||

| Ewing sarcoma family of tumors | 4 | 67 | 32 | 84 |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 17 | 3 | 8 |

| Other soft tissue sarcoma | 1 | 17 | 3 | 8 |

| Weight, kg | ||||

| Median | 46.7 | 44.6 | ||

| Range | 17.8-84.8 | 7.9-119.2 | ||

| Baseline ANC, ×109/L | ||||

| Median | 3.96 | 4.16 | ||

| Range | 3.55-8.50 | 1.27-13.88 | ||

| Baseline platelet count, ×109/L | ||||

| Median | 270 | 385.5 | ||

| Range | 172-353 | 149-859 | ||

Abbreviation: ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

Only 37 of the 38 patients randomly assigned to receive pegfilgrastim received study drug (Fig 1); one patient was withdrawn before pegfilgrastim administration because of concerns about protocol-required blood draws. Thirty-two (84%) patients randomly assigned to pegfilgrastim and three (50%) patients randomly assigned to filgrastim completed all planned cycles of chemotherapy and study drug treatment (Fig 1).

Efficacy

Efficacy analysis (Table 2) included data for all 43 patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Appendix Table A2 (online only) reports on the intent-to-treat data set for the study's primary end point: duration of severe neutropenia. The study was designed as an estimation (hypothesis-forming) study, rather than as a hypothesis-testing study. In the first cycle of chemotherapy, median duration of grade 4 neutropenia was 5.0 days in the pegfilgrastim group and 6.0 days in the filgrastim group. Median duration of grade 4 neutropenia was similar in the third cycle of chemotherapy (7.0 days for both pegfilgrastim and filgrastim).

Table 2.

Efficacy Endpoints in Cycles 1 and 3

| Efficacy Endpoint | Filgrastim |

Pegfilgrastim |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

0-5 Years |

6-11 Years |

12-21 Years |

|||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Cycle 1 | n = 6 | n = 37 | n = 12 | n = 10 | n = 15 | |||||

| Duration of grade 4 neutropenia, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 6.0 | 5.0 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 4.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-9 | 0-24 | 4-24 | 4-8 | 0-7 | |||||

| Time to ANC recovery, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 14 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 13 | |||||

| Range | 12-16 | 10-31 | 12-31 | 12-16 | 10-15 | |||||

| Patients without ANC recovery by day 21 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Febrile neutropenia | 5 | 83 | 21 | 57 | 9 | 75 | 7 | 70 | 5 | 33 |

| Cycle 3 | n = 4 | n = 34 | n = 11 | n = 10 | n = 13 | |||||

| Duration of grade 4 neutropenia, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 7.0 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 7.5 | 5.0 | |||||

| Range | 0-9 | 0-23 | 4-23 | 3-23 | 0-8 | |||||

| Time to ANC recovery, days | ||||||||||

| Median | 15 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 13 | |||||

| Range | 15-17 | 11-28+ | 12-28+ | 11-20+ | 11-17 | |||||

| Patients without ANC recovery by day 21 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 18 | 1 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Febrile neutropenia | 3 | 75 | 15 | 44 | 7 | 64 | 4 | 40 | 4 | 31 |

NOTE. Censored value indicated by “+.”

Abbreviation: ANC, absolute neutrophil count.

Over the course of the study, 25 (68%) of 37 patients in the pegfilgrastim group and five (83%) of six patients in the filgrastim group experienced FN. The median time to ANC recovery during cycle 1 of chemotherapy was 14 days in both treatment groups, with similar median recovery times in cycle 3 (Table 2).

In cycle 1, only one (3%) of 37 patients treated with pegfilgrastim failed to manifest neutrophil recovery. Among patients receiving pegfilgrastim, median duration of grade 4 neutropenia was inversely related to age group (ie, patients in the younger age groups experienced a longer median duration of grade 4 neutropenia) in both cycles 1 and 3.

Pharmacokinetics

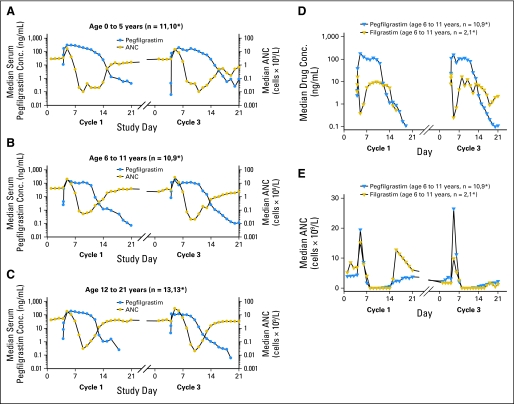

The pharmacokinetic analysis included data for all patients who received at least one dose of study drug and had more than 50% of pharmacokinetic samples collected (n = 40; 34 pegfilgrastim and six filgrastim). The maximum median pegfilgrastim concentration was achieved approximately 24 to 48 hours after pegfilgrastim administration and was sustained until the ANC nadir was reached (Figs 3A–3C). As the ANC started to recover, pegfilgrastim concentration declined rapidly, consistent with neutrophil-mediated clearance. Median drug exposures in cycle 3 were lower than those in cycle 1 for each age cohort.

Fig 3.

Pharmacokinetic and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) profiles in cycles 1 and 3. Pegfilgrastim profiles after 100 μg/kg pegfilgrastim administration to patients in the following age groups: (A) 0 to 5 years, (B) 6 to 11 years, and (C) 12 to 21 years. Pharmacokinetic and ANC profiles in patients in the 6 to 11 years age group receiving (D) pegfilgrastim and (E) filgrastim. Conc, concentration. (*) Number of patients beginning cycle 3.

Figures 3D and 3E show the median pharmacokinetic and ANC profiles of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim in cycles 1 and 3 for patients age 6 to 11 years. Compared with the serum pegfilgrastim concentration profile, the median serum filgrastim concentration declined rapidly after the first dose. After repeated administration, the daily trough filgrastim concentration increased until the ANC nadir occurred. Both pegfilgrastim and filgrastim serum concentrations declined rapidly after ANC recovery, consistent with neutrophil-mediated drug clearance. After the nadir, the ANC rise was gradual in patients treated with pegfilgrastim. Patients receiving filgrastim experienced elevations of ANC beyond the normal range because of continued filgrastim dosing during the neutrophil recovery phase. The youngest and oldest age cohorts had similar profiles (data not shown).

Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined for pegfilgrastim only. For filgrastim, the data were not sufficient for determination of pharmacokinetic parameters. The youngest cohort (0-5 years) had a higher exposure to pegfilgrastim than the other two cohorts (6-11 years and 12-21 years; Table 3), likely related to the fact that these younger patients experienced a longer duration of neutropenia (Table 2).

Table 3.

Pegfilgrastim Pharmacokinetic Parameter Values in Cycles 1 and 3 After Administration of 100 μg/kg Pegfilgrastim to Pediatric Patients

| Summary Statistic | Cmax (ng/mL) |

tmax (hours) |

AUC0-∞ (ng · h/mL) |

t1/2 (hours) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Median | Range | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| 0-5 years | ||||||||

| Cycle 1 (n = 11) | 401 | 190 | 48.0 | 24.0-216.0 | 47,900 | 22,500 | 30.1 | 38.2 |

| Cycle 3 (n = 10) | 311 | 208 | 24.0 | 4.0-96.0 | 36,300 | 30,400 | 30.8 | 19.9 |

| 6-11 years | ||||||||

| Cycle 1 (n = 10) | 205 | 146 | 24.0 | 24.0-144 | 22,000 | 13,100 | 20.2 | 11.3 |

| Cycle 3 (n = 9) | 204 | 142 | 24.0 | 4.0-120.0 | 21,200 | 14,500 | 23.1 | 13.5 |

| 12-21 years | ||||||||

| Cycle 1 (n = 13) | 229 | 176 | 48.0 | 24.0-144.0 | 29,300 | 23,200 | 21.2 | 16.0 |

| Cycle 3 (n = 13) | 171 | 102 | 24.0 | 4.0-120.0 | 20,300 | 14,300 | 19.3 | 10.2 |

NOTE. The extrapolated area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) for AUC0-∞ calculation was less than 1%.

Abbreviations: Cmax, maximum serum concentration; tmax, time to maximum serum concentration; t1/2, terminal half-life; SD, standard deviation.

Safety

Safety analysis included data for all 43 patients who received at least one dose of study drug. Consistent with expectations for pediatric patients receiving myelosuppressive sarcoma chemotherapy, most patients (84% pegfilgrastim, 83% filgrastim) had one or more grade 3 or higher AEs (Table 4). Most AEs were attributed to the underlying disease process or the chemotherapy administered. AEs attributable to study drug were reported for 22% and 33% of patients who received pegfilgrastim and filgrastim, respectively. Bone pain was the most common AE (11% pegfilgrastim, 17% filgrastim); other AEs were consistent with the known effects of these drugs. There were no significant differences in the overall safety profile noted between treatment arms or across age groups in the pegfilgrastim treatment arm. One fatal AE (respiratory acidosis in a patient who received pegfilgrastim) was noted; however, it was considered to be unrelated to pegfilgrastim by the investigator.

Table 4.

Severe, Life-Threatening, or Fatal (Grade 3 to 5) Adverse Events Experienced by More Than One Patient

| Adverse Event | Filgrastim (n = 6) |

Pegfilgrastim (n = 37) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |

| Total No. of patients reporting severe, life-threatening, or fatal adverse events | 5 | 83 | 31 | 84 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 4 | 67 | 21 | 57 |

| Anemia | 2 | 33 | 21 | 57 |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 6 | 16 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 6 | 16 | |

| Vomiting | 0 | 4 | 11 | |

| Catheter-related infection | 0 | 4 | 11 | |

| Alopecia | 1 | 17 | 3 | 8 |

| Constipation | 0 | 3 | 8 | |

| Diarrhea | 1 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Pyrexia | 1 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Dehydration | 1 | 17 | 2 | 5 |

| Colitis | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Otitis media | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Decreased platelet count | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Anorexia | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Hypokalemia | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Anxiety | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Hallucination | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Respiratory distress | 1 | 17 | 1 | 3 |

Antibody analysis included data for all patients who received study drug and had one or more antibody samples available (n = 41; 36 pegfilgrastim and five filgrastim). Ten (24%) of these 41 patients tested positive for binding antibodies against filgrastim or pegfilgrastim at baseline before study drug administration. Five of these patients also tested positive for neutralizing antibodies at baseline but became antibody negative after initiation of chemotherapy. One (2%) patient developed transient binding antibodies against filgrastim at a single time point after receiving pegfilgrastim but tested negative for pegfilgrastim neutralizing antibodies. The presence of antibodies had no apparent effect on clinical outcomes or the pharmacokinetics of pegfilgrastim.

DISCUSSION

Randomized clinical trials in both children and adults have demonstrated that filgrastim prophylaxis for chemotherapy-induced neutropenia results in reduction of the depth of the ANC nadir,12,33 duration of grade 4 neutropenia,13,14 number of episodes of FN,15,34 number and duration of hospitalizations,13,33,35 number of documented infections,12,15,33,35 and use of antibiotics.13–15,36 Filgrastim use has become routine in the management of pediatric sarcomas requiring chemotherapy.4–6,11,25

Our study indicates that pegfilgrastim 100 μg/kg administered once per chemotherapy cycle has similar efficacy and safety to filgrastim at 5 μg/kg administered daily in pediatric patients receiving sarcoma-directed chemotherapy (VDC/IE). Median duration of grade 4 neutropenia was 5.0 days in the pegfilgrastim group and 6.0 days in the filgrastim group in cycle 1 and 7.0 days for both groups in cycle 3. Over the course of the study, FN occurred in similar proportions of patients in the two treatment groups (68% pegfilgrastim; 83% filgrastim). Two studies11,25 that used a similar dose-intensive regimen of VDC/IE in pediatric patients reported a median duration of grade 4 neutropenia of 5.0 days for pegfilgrastim and 6.0 days for filgrastim, a difference that was not clinically significant. Wexler et al11 also reported a similar incidence of FN in patients receiving pegfilgrastim and filgrastim (57% and 83%, respectively) after chemotherapy cycle 1. Of note, our study included a younger patient population (from 28 days to 21 years of age, compared with 1 to 25 years in Wexler et al11 and 3 to 25 years in Fox et al25).

Pharmacokinetic profiles of pegfilgrastim and filgrastim in this study are consistent with those in adults.22,30,31,37 Whereas filgrastim is cleared by neutrophils and predominantly by the kidneys, thus having a relatively short serum half-life, pegfilgrastim is cleared almost exclusively by neutrophils.18–20 Serum concentrations of pegfilgrastim are therefore sustained throughout the ANC nadir, with rapid clearance of the drug on neutrophil recovery. Neutrophil recovery, defined as an ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109/L after nadir, occurred in 36 of 37 patients during cycle 1; the single patient without neutrophil recovery was in the 0-5 years age group. Median drug exposures in cycle 3 were lower than those in cycle 1. This finding may be explained by the expansion of neutrophils and neutrophil precursor mass over time leading to more rapid drug clearance, consistent with a neutrophil-mediated clearance mechanism.38 Among patients receiving pegfilgrastim, those in the 0-5 years age group experienced a longer median duration of neutropenia than older patients. Since the youngest patient cohort also had a higher median exposure to pegfilgrastim than did the other two cohorts, the more protracted neutropenia experienced by the youngest children in this study is likely to be due to a greater relative exposure to myelosuppressive chemotherapy rather than to inadequate pegfilgrastim dosing. However, caution should be exercised regarding comparisons between age groups because of the small sample sizes.

All patients in the 0-5 years age group received chemotherapy dosing according to body-surface area, although, per protocol guidelines, patients who were ≤ 1 year of age or weighed ≤ 10 kg could be dosed according to institutional guidelines. When chemotherapy doses were examined by weight (Appendix Table A3, online only), the doses of doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide that were received by the youngest age group were higher than those received by both older age groups and nearly 50% higher than those received by the oldest age group. Similar findings (maintenance of serum pegfilgrastim concentrations in the setting of prolonged neutropenia after highly myelosuppressive chemotherapy) have been observed in adults treated for acute myeloid leukemia.37

Most patients experienced grade 3 or higher AEs, as is expected for pediatric patients receiving VDC/IE chemotherapy for treatment of sarcoma.11 Twenty-two percent of patients who received pegfilgrastim and 33% of patients who received filgrastim experienced AEs attributed to growth factor use, of which bone pain was the most common. Studies in adults have documented similar AE profiles; mild to moderate bone pain is among the most common documented AEs.30,31,37 In our pediatric patients treated with pegfilgrastim, there was no evidence of differences in toxicity across the three age groups. Although about one quarter of patients had antibodies against filgrastim or pegfilgrastim at baseline and one patient developed transient antibodies to filgrastim after receiving pegfilgrastim, these antibodies had no apparent effect on clinical outcomes or the pharmacokinetics of pegfilgrastim. Seroreactivity has been documented in adults receiving pegfilgrastim, but the presence of antibodies has not had any clinical sequelae.22

Growth factor use results in a relative decrease in the incidence of rather than absolute prevention of FN. This study suggests that a single injection of 100 μg/kg pegfilgrastim is similar to daily injections of filgrastim at 5 μg/kg for the reduction of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and its associated complications in pediatric patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Administration of a single dose of growth factor with self-regulated clearance is likely to be of substantial benefit in the pediatric population. Although no published data exist, clinical experience has shown that eliminating the need for daily injections may improve patient and family compliance, lead to fewer growth factor therapy interruptions, and decrease the burden of therapy on both the child and the family.

Acknowledgment

We thank Joan O'Byrne for providing editorial support.

Appendix

Table A1.

Protocol Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Newly diagnosed sarcoma |

| Younger than age 22 years |

| Life expectancy of at least 6 weeks with appropriate therapy |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤ 1 |

| Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine less than 2.5 times normal |

| AST, ALT, and bilirubin less than 2.5 times normal |

| Absolute neutrophil count at least 1 × 109/L |

| Platelet count at least 100 × 109/L |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Bone marrow involvement with tumor |

| Major surgery within prior 2 weeks |

| Previous chemotherapy or radiotherapy |

| Evidence of hematologic malignancy, myelodysplasia, or other malignancies |

| Known human immunodeficiency virus infection |

| Treatment with antibiotics or anti-infectives for an active infection within prior 72 hours |

| Treatment with corticosteroids or lithium within prior 1 week |

| Cytokine therapy within prior 2 weeks (filgrastim within prior 1 week) |

| Concurrent enrollment on any other study with investigational drugs or devices |

| Psychiatric, addictive, or other disorder compromising ability to give informed consent for study participation |

| Known hypersensitivity to E. coli–derived drugs |

| Patients of childbearing potential not using adequate contraceptive precautions |

| Pregnancy or lactation |

| Lack of availability for follow-up assessment |

| Inability to comply with protocol procedures |

Table A2.

Efficacy Endpoints for the Intent-to-Treat Population in Cycles 1 and 3

| Efficacy Endpoint | Filgrastim |

Pegfilgrastim |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All |

0-5 Years |

6-11 Years |

12-21 Years |

|||||||

| Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | Median | Range | |

| Cycle 1 | n = 6 | n = 35 | n = 12 | n = 10 | n = 13 | |||||

| Duration of grade 4 neutropenia, days | 6.0 | 0-9 | 6.0 | 0-24 | 8.0 | 4-24 | 6.0 | 4-8 | 4.0 | 0-7 |

| Cycle 3 | n = 4 | n = 32 | n = 11 | n = 10 | n = 11 | |||||

| Duration of grade 4 neutropenia, days | 7.0 | 0-9 | 7.0 | 0-23 | 9.0 | 4-23 | 7.5 | 3-23 | 5.0 | 0-8 |

Table A3.

Chemotherapy Dose by Age Group, BSA, and Weight

| Chemotherapy (protocol dose) | Age (years) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-5 (n = 13) |

6-11 (n = 12) |

12-21 (n = 19) |

||||||||||

| By BSA (mg/m2) |

By Weight (mg/kg) |

By BSA (mg/m2) |

By Weight (mg/kg) |

By BSA (mg/m2) |

By Weight (mg/kg) |

|||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Doxorubicin (75 mg/m2) | 72.60 | 8.70 | 3.13 | 0.31 | 77.60 | 9.20 | 2.47 | 0.31 | 71.40 | 10.10 | 1.97 | 0.35 |

| Cyclophosphamide (1,200 mg/m2) | 1,160.00 | 134.00 | 50.10 | 4.90 | 1,243.00 | 149.00 | 39.60 | 4.90 | 1,180.00 | 70.00 | 32.60 | 4.50 |

| Vincristine (2.0 mg/m2) | 1.94 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 1.69 | 0.21 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 1.21 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

Abbreviation: BSA, body surface area; SD, standard deviation.

Footnotes

Supported in part by Amgen (S.L.S., H.I., J.F., L.S., and V.M.S.), by Cancer Center Grant No. CA23099 (S.L.S. and V.M.S.), by Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30 CA21765 from the National Cancer Institute (S.L.S. and V.M.S.), and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (S.L.S. and V.M.S.).

Presented in abstract form and as a poster at the 16th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (ASPHO), May 3, 2003, Seattle, WA; at the 21st Annual Meeting of the ASPHO, May 16, 2008, Cincinnati, OH; and at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29-June 2, 2009, Orlando, FL.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00035620.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Matthew Guo, Amgen (C); Bing-Bing Yang, Amgen (C); Lyndah Dreiling, Amgen (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: None Stock Ownership: Matthew Guo, Amgen; Bing-Bing Yang, Amgen; Lyndah Dreiling, Amgen Honoraria: None Research Funding: Sheri L. Spunt, Amgen; Victor M. Santana, Amgen Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Sheri L. Spunt, Helen Irving, Leonard Sender, Matthew Guo, Bing-Bing Yang, Lyndah Dreiling, Victor M. Santana

Provision of study materials or patients: Sheri L. Spunt, Helen Irving, Jami Frost, Leonard Sender, Victor M. Santana

Collection and assembly of data: Sheri L. Spunt, Helen Irving, Jami Frost, Leonard Sender, Matthew Guo, Bing-Bing Yang, Victor M. Santana

Data analysis and interpretation: Sheri L. Spunt, Helen Irving, Jami Frost, Leonard Sender, Matthew Guo, Bing-Bing Yang, Lyndah Dreiling, Victor M. Santana

Manuscript writing: Sheri L. Spunt

Final approval of manuscript: Sheri L. Spunt, Helen Irving, Jami Frost, Leonard Sender, Matthew Guo, Bing-Bing Yang, Lyndah Dreiling, Victor M. Santana

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacci G, Picci P, Avella M, et al. The importance of dose-intensity in neoadjuvant chemotherapy of osteosarcoma: A retrospective analysis of high-dose methotrexate, cisplatinum and adriamycin used preoperatively. J Chemother. 1990;2:127–135. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.1990.11738996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker KS, Anderson JR, Link MP, et al. Benefit of intensified therapy for patients with local or regional embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma: Results from the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study IV. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2427–2434. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith MA, Ungerleider RS, Horowitz ME, et al. Influence of doxorubicin dose intensity on response and outcome for patients with osteogenic sarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:1460–1470. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.20.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al. Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:694–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari S, Smeland S, Mercuri M, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with high-dose Ifosfamide, high-dose methotrexate, cisplatin, and doxorubicin for patients with localized osteosarcoma of the extremity: A joint study by the Italian and Scandinavian Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8845–8852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.5785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crist WM, Anderson JR, Meza JL, et al. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study-IV: Results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3091–3102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.12.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodey GP, Buckley M, Sathe YS, et al. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64:328–340. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-2-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabrilove JL, Jakubowski A, Scher H, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on neutropenia and associated morbidity due to chemotherapy for transitional-cell carcinoma of the urothelium. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806023182202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bronchud MH, Potter MR, Morgenstern G, et al. In vitro and in vivo analysis of the effects of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in patients. Br J Cancer. 1988;58:64–69. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1988.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord BI, Bronchud MH, Owens S, et al. The kinetics of human granulopoiesis following treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9499–9503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wexler LH, Weaver-McClure L, Steinberg SM, et al. Randomized trial of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in pediatric patients receiving intensive myelosuppressive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:901–910. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.3.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohno R, Tomonaga M, Kobayashi T, et al. Effect of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after intensive induction therapy in relapsed or refractory acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:871–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009273231304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crawford J, Ozer H, Stoller R, et al. Reduction by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor of fever and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy in patients with small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:164–170. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107183250305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trillet-Lenoir V, Green J, Manegold C, et al. Recombinant granulocyte colony stimulating factor reduces the infectious complications of cytotoxic chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(93)90376-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welte K, Reiter A, Mempel K, et al. A randomized phase-III study of the efficacy of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster Study Group. Blood. 1996;87:3143–3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Womer RB, Daller RT, Fenton JG, et al. Granulocyte colony stimulating factor permits dose intensification by interval compression in the treatment of Ewing's sarcomas and soft tissue sarcomas in children. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmes FA, O'Shaughnessy JA, Vukelja S, et al. Blinded, randomized, multicenter study to evaluate single administration pegfilgrastim once per cycle versus daily filgrastim as an adjunct to chemotherapy in patients with high-risk stage II or stage III/IV breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:727–731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.3.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang BB, Lum PK, Hayashi MM, et al. Polyethylene glycol modification of filgrastim results in decreased renal clearance of the protein in rats. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:1367–1373. doi: 10.1002/jps.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molineux G, Kinstler O, Briddell B, et al. A new form of Filgrastim with sustained duration in vivo and enhanced ability to mobilize PBPC in both mice and humans. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1724–1734. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lord BI, Woolford LB, Molineux G. Kinetics of neutrophil production in normal and neutropenic animals during the response to filgrastim (r-metHu G-CSF) or filgrastim SD/01 (PEG-r-metHu G-CSF) Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2085–2090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roskos LK, Lum P, Lockbaum P, et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of pegfilgrastim in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:747–757. doi: 10.1177/0091270006288731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston E, Crawford J, Blackwell S, et al. Randomized, dose-escalation study of SD/01 compared with daily filgrastim in patients receiving chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2522–2528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green MD, Koelbl H, Baselga J, et al. A randomized double-blind multicenter phase III study of fixed-dose single-administration pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in patients receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:29–35. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.André N, Kababri ME, Bertrand P, et al. Safety and efficacy of pegfilgrastim in children with cancer receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2007;18:277–281. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e328011a532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox E, Jayaprakash N, Widemann BC, et al. Randomized trial and pharmacokinetic study of pegfilgrastim vs. filgrastim in children and young adults with newly diagnosed sarcoma treated with dose intensive chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl):507s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0761. abstr 9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borinstein SC, Pollard J, Winter L, et al. Pegfilgrastim for prevention of chemotherapy-associated neutropenia in pediatric patients with solid tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:375–378. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallorso S, Berger M, Caviglia I, et al. Prospective single-arm study of pegfilgrastim activity and safety in children with poor-risk malignant tumours receiving chemotherapy. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:507–513. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.te Poele EM, Kamps WA, Tamminga RY, et al. Pegfilgrastim in pediatric cancer patients. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:627–629. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000188631.41510.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wendelin G, Lackner H, Schwinger W, et al. Once-per-cycle pegfilgrastim versus daily filgrastim in pediatric patients with Ewing sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2005;27:449–451. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000175711.73039.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holmes FA, Jones SE, O'Shaughnessy J, et al. Comparable efficacy and safety profiles of once-per-cycle pegfilgrastim and daily injection filgrastim in chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: A multicenter dose-finding study in women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:903–909. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vose JM, Crump M, Lazarus H, et al. Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of pegfilgrastim compared with daily filgrastim after chemotherapy for lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:514–519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidance for industry: E11 clinical investigation of medicinal products in the pediatric population, 2000. International Conference on Harmonisation; http://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm129477.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heil G, Hoelzer D, Sanz MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of filgrastim in remission induction and consolidation therapy for adults with de novo acute myeloid leukemia. The International Acute Myeloid Leukemia Study Group. Blood. 1997;90:4710–4718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettengell R, Gurney H, Radford JA, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor to prevent dose-limiting neutropenia in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A randomized controlled trial. Blood. 1992;80:1430–1436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pui CH, Boyett JM, Hughes WT, et al. Human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor after induction chemotherapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1781–1787. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706193362503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michon JM, Hartmann O, Bouffet E, et al. An open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 2 study of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (filgrastim) as an adjunct to combination chemotherapy in paediatric patients with metastatic neuroblastoma. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1063–1069. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00061-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sierra J, Szer J, Kassis J, et al. A single dose of pegfilgrastim compared with daily filgrastim for supporting neutrophil recovery in patients treated for low-to-intermediate risk acute myeloid leukemia: Results from a randomized, double-blind, phase 2 trial. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:195. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molineux G, Dexter TM. Biology of G-CSF. In: Morstyn G, Dexter TM, editors. Filgrastim (r-metHuG-CSF) in Clinical Practice. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]