Abstract

Gap junctions between neurons function as electrical synapses, and are present in all layers of mammalian and teleost retina. These synapses are largest and most prominent between horizontal cells where they function to increase the receptive field of a single neuron beyond the width of its dendrites. Receptive field size and the extent of gap junctional coupling between horizontal cells is regulated by ambient light levels and may mediate light/dark adaptation. Furthermore, teleost horizontal cell gap junction hemichannels may facilitate a mechanism of feedback inhibition between horizontal cells and cone photoreceptors. As a prelude to using mouse genetic models to study horizontal cell gap junctions and hemichannels, we sought to determine the connexin complement of mouse horizontal cells. Cx36, Cx37, Cx43, Cx45 and Cx57 mRNA could be detected in mouse retina by RT-PCR. Microscopy was used to further examine the distribution of Cx26 and Cx36. Cx26 immunofluorescence and a β-gal reporter under regulatory control of the Cx36 promoter did not colocalize with a horizontal cell marker, indicating that these genes are not expressed by horizontal cells. The identity of the connexin(s) forming electrical synapses between mouse horizontal cells and the connexin that may form hemichannels in the horizontal cell telodendria remains unknown.

Keywords: connexin26, connexin36, horizontal cell, gap junction, hemichannel

INTRODUCTION

Connexin proteins are the membrane spanning sub-units of the gap junction intercellular channel. Six connexins oligomerize to form a connexon or hemi-channel, that when docked with a connexon from an adjacent cell forms the complete intercellular channel. Sixteen connexin genes have been cloned in the mouse and five additional non-orthologous connexin genes have been identified by human genome sequencing and described at the 2001 International Gap Junction Conference. Gap junction intercellular channels allow the diffusion of ions and small molecules of molecular mass less than 1kD. Because they readily conduct ionic currents, gap junctions that form between neurons function as electrical synapses.

In the retina, gap junctions have been documented by dye and tracer injection, physiological recordings and electron microscopy. They are present in all layers of the retina and between most retinal cell types although horizontal cells establish the largest and most prominent junctions. Horizontal cell bodies are positioned at the most scleral aspect of the inner nuclear layer, with axonal and dendritic processes that tile the outer plexiform layer and elaborate gap junctions onto adjacent horizontal cells. Horizontal cell telodendria form lateral processes that flank the ribbon synapses of rod and cone photoreceptors. These processes receive excitatory glutamatergic input from the photoreceptors and in addition are believed to make reciprocal inhibitory connections. Feedback inhibition is thought to generate the inhibitory surround, a characteristic property of many retinal neurons in which illumination of peripheral regions produces a response opposite in polarity to that evoked by illumination of the center.

It has been proposed that the size of the horizontal cell receptive field is critically dependent on electrical synapses between adjacent cells. In support of this idea, it has been well established that the size of the receptive field for a single horizontal cell can be much larger than the physical width of its dendritic field, which could be explained by extensive electrical coupling. In addition, the size of the receptive field is roughly correlated with neurobiotin diffusion (Bloomfield et al., 1995). Most importantly, both receptive field size and the extent of neurobiotin diffusion are coordinately regulated by ambient light levels. Both field size and tracer coupling follow a triphasic pattern; minimal in completely dark or light adapted retina, but many times larger at the dark-adapted states in between (Xin and Bloomfield, 1999). Together, these data suggest that the size of the horizontal cell receptive field may be directly controlled by the extent of electrical coupling.

In vitro studies using pairs of isolated teleost horizontal cells suggest horizontal cell coupling is acutely regulated by multiple, independent mechanisms. For example, activation of D1 Dopamine receptors raise cAMP levels and consequently protein kinase A (PKA) activity which inhibits electrical coupling by decreasing the open probability and mean open time of intercellular channels (McMahon and Brown, 1994). In addition, horizontal cell coupling is inhibited by nitric oxide via a cGMP, PKG dependent signaling cascade that decreases intercellular channel open probability, but has no effect on mean open time (Lu and McMahon, 1997). Retinoic acid is a third neuromodulatory agent that inhibits horizontal cell coupling but appears to do so by binding directly to the extracellular face of the channel (Zhang and McMahon, 2000). Although much is known about the modulation and single channel physiology of teleost horizontal cell gap junctions, the identity of the connexin forming these channels is unknown.

While the involvement of the horizontal cell in cone surround responses is well established, the cellular mechanisms underlying these responses are widely disputed. In one model, GABA released from horizontal cells provides negative feedback to cones through activation of chloride currents. In support of this model, application of GABA produces Cl− currents in L- and M-type cones in the turtle retina. Furthermore, some horizontal cells actually contain GABA (Studholme and Yazulla, 1988). However, conventional synaptic vesicles cannot be observed and thus it is not clear how presynaptic GABA would be released. To account for this, a release mechanism involving the GABA transporter has been proposed (Schwartz, 1987).

In the major competing model, the feedback mechanism involves modulation of cone Ca++ currents by potential changes of the extracellular synaptic space, rather than the release of a neurotransmitter. Consistent with this idea, it was shown under voltage clamp that surround stimulation directly modulated cone Ca++ currents (Verweij et al., 1996). To explain this, Kamermans et al. (Kamermans et al., 2001) proposed that connexin hemichannels located in horizontal cell dendrites could locally change the effective cone membrane potential near the synaptic ribbon by acting as a current sink. This would affect gating of cone voltage sensitive Ca++ channels leading to changes in Ca++ influx and thus glutamate release. As described above, hemichannels span a single plasma membrane and are precursors to the intercellular channels comprising electrical synapses. The notion that hemichannels underlie horizontal cell feedback to cones is supported by three observations. First, large, non-selective, voltage-dependent conductances similar to connexin hemichannels have been reported in teleost horizontal cells (DeVries and Schwartz, 1992). Second, surround-induced feedback to cones in goldfish retina is not affected by GABA antagonists but is eliminated by treatment with carbenoxolone, a widely used inhibitor of intercellular channels (Kamermans et al., 2001). Third, an ortholog of Cx26 was localized by EM immunocytochemistry at the terminal dendrites of carp retinal horizontal cells (Janssen-Bienhold et al., 2001), precisely where hemichannel must be located to facilitate electrical feedback inhibition. Interestingly, the localization of Cx26 is not consistent with its involvement in the junctions that join adjacent horizontal cells. Each of these studies have caveats, for example, carbenoxolone most likely does not act directly on hemi- or intercellular channels and may affect other channels and intracellular signaling. Similarly, Cx26 is not one of the connexins for which hemichannel activity has been directly demonstrated. Nevertheless, together these data strongly implicate connexins in a novel horizontal cell-photoreceptor feedback mechanism.

To definitively test the models of feedback inhibition and/or the function of electrical coupling between horizontal cells in setting receptive field size it is desirable to experimentally inhibit connexin activity. Clearly, it remains difficult to pharmacologically inhibit either gap junctions or hemi-channels in a specific and selective manner. Thus, it is of interest to establish the connexin profile of mouse horizontal cells so the roles of coupling can be further studied using genetic models. Therefore, we examined the expression of 16 connexins in the mouse retina using RT-PCR and the distribution of Cx26 and Cx36 using microscopic techniques.

METHODS

RT-PCR

RNA prepared from adult C57Bl6 and 129SvEv retina was used as template for reverse transcription (Gibco Superscript RT) and PCR (Clontech Advantage II). Duplicate reactions were performed without reverse transcriptase as a control against contamination from genomic DNA. PCR primers were designed for each of the 16 cloned mouse connexins and primer pair sensitivity was tested against serial dilutions of genomic DNA. Only those pairs that could amplify a minimum of 300 copies of template were used for this analysis. Primer pair specificity was ensured by restriction endonuclease digestion of amplified products, and amplification of cRNA from other tissues was used as positive controls for all primer pairs (data not shown). No difference was seen between cRNA prepared using random hexamers or oligo-dT as primers for reverse transcription. PCR primer sequences are available upon request.

Immunofluorescence

Adult wild type and Cx36 +/− mice (C57Bl6X129SvEv hybrids) were deeply anesthetized with i.p. injection of Rompun/Ketaset (10–50 mg/ml). Animals were perfused with Ame’s media (Sigma) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 1X Sorenson’s buffer at pH 7.4, eyes were removed and post-fixed for 2 hrs as an eye-cup, at room temperature and thoroughly washed in PBS. Tissues were cryoprotected overnight in 30% sucrose and 20 um frozen sections were prepared and mounted on microscope slides. Slides were washed thoroughly in PBS, blocked with 10% donkey serum, 2% BSA and incubated overnight with antibodies to calbindin (mouse, Sigma, 1:500), connexin26 (rabbit, Zymed, 1:500) or β-gal (rabbit, Chemicon 1:2500). β-gal anti-sera was pretreated by absorption to WT tissue. Primary antibodies were detected with anti-mouse Cy3 or anti-rabbit Cy2 secondaries (Jackson Immunoresearch) and images were collected by confocal microscopy as well as conventional epifluorescence.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

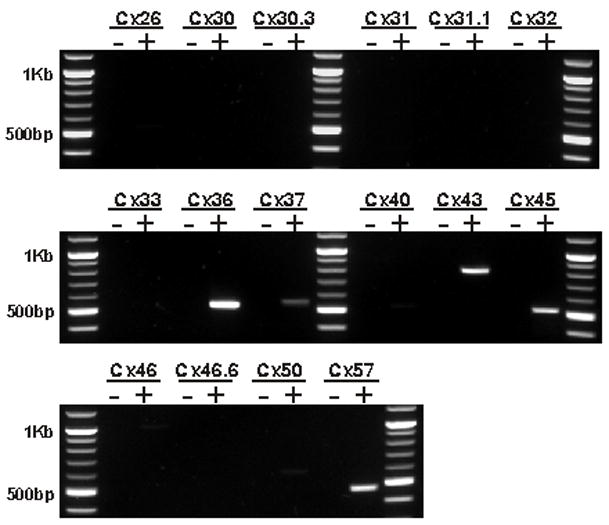

In order to survey the connexins expressed in the mouse retina we designed PCR primer pairs against each of the cloned mouse connexins and used them to amplify cRNA generated from adult mouse retina (figure 1). Of the 16 connexins screened by PCR, we found 5 to be present in the retina. These are Cx36, Cx37, Cx43, Cx45 and Cx57. Cx36 is expressed by retinal neurons (Condorelli et al., 1998) (Feigenspan et al., 2001) (Mills et al., 2001) and the expression of Cx45 by retinal neurons was suggested by Beta-galactocidase (β-gal) expression in a Cx45 KO mouse line (Guldenagel et al., 2000). Immuno-EM data demonstrates that Cx43 is not expressed by neurons but rather is confined to astrocytes in the CNS (Rash et al., 2000) and this is confirmed by immunofluorescence data in the mammalian retina (Janssen-Bienhold et al., 1998). Cx37 is expressed by endothelial cells (Reed et al., 1993) and is presumably being expressed by the retinal vasculature. Cx57 has not previously been reported in the mouse retina and the cell types expressing this connexin are unknown.

Figure 1.

Mouse retina RNA was screened by RT-PCR for the presence of each of the 16 cloned connexin genes. mRNA was detected for 5 connexins; Cx36, Cx37, Cx43, Cx45 and Cx57. To control against amplification of genomic DNA, cRNA was generated in two reactions, one containing (+) and the other lacking (−) the reverse transcriptase enzyme. Results were identical between oligo-dT and random hexamer primed cRNA.

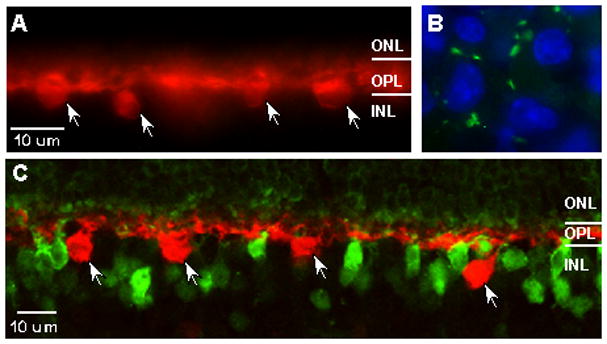

Despite the absence of Cx26 message in mammalian retinal mRNA, the well-documented presence of a Cx26 ortholog in teleosts encouraged us to test further for the presence of Cx26 in mouse horizontal cells. Unlike retinae from other species, the mouse only has one type of horizontal cell. These cells are axon bearing and can be labeled with antibodies to the calcium binding protein calbindin (Haverkamp and Wassle, 2000). We looked for Cx26 immunofluorescence along horizontal cell processes labeled with anti-calbindin antibodies (figure 2a). Cx26-containing gap junctions could be easily detected in sections of mouse liver (figure 2b) however; no Cx26 protein could be detected on calbindin positive processes or anywhere throughout the outer plexiform layer.

Figure 2.

Cx26 immunopositive puncta (green) could not be detected on calbindin positive processes(red) in the OPL(A), but could be easily located in control sections from mouse liver (B) counterstained with the nuclear label DAPI (blue). In retina from mice in which one copy of Cx36 was replaced with β-gal, immunofluorescence for this reporter (green) does not colocalize with calbindin (red) positive horizontal cells (C). ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer. Arrows indicate horizontal cell bodies.

The detection of Cx36 message in the retina, the restriction of this connexin to neuronal cell types and the presence of Cx36 protein in the outer plexiform layer (data not shown) prompted us to look for Cx36 in horizontal cells as well. We recently generated a line of Cx36 knockout mice in which the Cx36 coding sequence was replaced by a bicistronic reporter cassette containing β-gal (Deans et al., 2001). β-gal immunofluorescence in sections of retina heterozygous for the Cx36 deletion was compared to that of calbindin (figure 2c). Although β-gal positive cells are present in the scleral aspects of the inner nuclear layer, these immunopositive cell bodies do not colocalize with the horizontal cell marker, indicating that horizontal cells also do not express Cx36.

The molecular composition of intercellular channels and hemichannels (should they exist) in the mammalian horizontal cell remains unknown. Neither Cx36 nor, somewhat surprisingly, Cx26 are present in this cell type. Although Cx45 expression appears to be neuronal in the retina, expression is restricted to the amacrine and ganglion cell layers (Guldenagel et al., 2000), inconsistent with the location of horizontal cells. The distribution of Cx57 in the retina has not been examined. Interestingly, 2 connexin genes, mouse Cx57 and human Cx58.8 (a novel human connexin identified by genome sequencing) share 85% and 77% similarity respectively to a zebrafish connexin (zf Cx55.5) that may be expressed by horizontal cells (Dermietzel et al., 2000).

An additional complication to the comparison of connexin expression between teleost and mammalian retina are the presence of teleost connexins that do not have mammalian orthologs. Perch retina expresses two highly related connexins, pCx35 and pCx34.7. While pCx35 appears to be the ortholog of mammalian Cx36, pCx34.7 has no identifiable ortholog in the human or mouse genomes. The presence of 2 highly related connexins in the perch retina appears to be the result of duplications that occurred within the Teleost genome and is a phenomenon that has also been observed for other gene families (Robinson-Rechavi et al., 2001).

Our results indicate that Cx26 and Cx36 are not present in the mouse horizontal cell and therefore cannot contribute to feedback inhibition or horizontal cell coupling. In addition, connexin profiles of mammalian and teleost retina are significantly different; both Cx26 and Cx43 (Janssen-Bienhold et al., 1998) are present in mammalian but not teleost retinal neurons. A lack of Cx26 in the mouse retina does not disprove the electrical feedback model. However, it suggests that either this mechanism of inhibition is restricted to the teleost retina or that a different connexin serves this function in mammals.

References

- Bloomfield SA, et al. A comparison of receptive field and tracer coupling size of horizontal cells in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 1995;12:985–999. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800009524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condorelli DF, et al. Cloning of a new gap junction gene (Cx36) highly expressed in mammalian brain neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:1202–1208. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans MR, et al. Synchronous activity of inhibitory networks in neocortex requires electrical synapses containing connexin36. Neuron. 2001;31:477–485. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R, et al. Molecular and functional diversity of neural connexins in the retina. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8331–8343. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08331.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries SH, Schwartz EA. Hemi-gap-junction channels in solitary horizontal cells of the catfish retina. J Physiol. 1992;445:201–230. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp018920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenspan A, et al. Expression of neuronal connexin36 in AII amacrine cells of the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:230–239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00230.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldenagel M, et al. Expression patterns of connexin genes in mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Wassle H. Immunocytochemical analysis of the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Bienhold U, et al. Distribution of connexin43 immunoreactivity in the retinas of different vertebrates. J Comp Neurol. 1998;396:310–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen-Bienhold U, et al. Identification and localization of connexin26 within the photoreceptor-horizontal cell synaptic complex. Vis Neurosci. 2001;18:169–178. doi: 10.1017/s0952523801182015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamermans M, et al. Hemichannel-mediated inhibition in the outer retina. Science. 2001;292:1178–1180. doi: 10.1126/science.1060101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, McMahon DG. Modulation of hybrid bass retinal gap junctional channel gating by nitric oxide. J Physiol. 1997;499:689–699. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon DG, Brown DR. Modulation of gap-junction channel gating at zebrafish retinal electrical synapses. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2257–2268. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SL, et al. Rod pathways in the mammalian retina use connexin 36. J Comp Neurol. 2001;436:336–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash JE, et al. Immunogold evidence that neuronal gap junctions in adult rat brain and spinal cord contain connexin-36 but not connexin-32 or connexin-43. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7573–7578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed KE, et al. Molecular cloning and functional expression of human connexin37, an endothelial cell gap junction protein. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:997–1004. doi: 10.1172/JCI116321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson-Rechavi M, et al. Euteleost fish genomes are characterized by expansion of gene families. Genome Res. 2001;11:781–788. doi: 10.1101/gr.165601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz EA. Depolarization without calcium can release gamma-aminobutyric acid from a retinal neuron. Science. 1987;238:350–355. doi: 10.1126/science.2443977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studholme KM, Yazulla S. Localization of GABA and glycine in goldfish retina by electron microscopic postembedding immunocytochemistry: improved visualization of synaptic structures with LR white resin. J Neurocytol. 1988;17:859–870. doi: 10.1007/BF01216712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij J, et al. Horizontal cells feed back to cones by shifting the cone calcium-current activation range. Vision Res. 1996;36:3943–3953. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xin D, Bloomfield SA. Dark- and light-induced changes in coupling between horizontal cells in mammalian retina. J Comp Neurol. 1999;405:75–87. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19990301)405:1<75::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang DQ, McMahon DG. Direct gating by retinoic acid of retinal electrical synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14754–14759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.010325897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]