Abstract

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) can induce expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), which seems to promote the development of diabetic nephropathy, but the exact signaling mechanisms that mediate this induction are unknown. Here, AGEs induced CTGF expression in tubular epithelial cells (TECs) that either lacked the TGF-β1 gene or expressed dominant TGF-β receptor II, demonstrating independence of TGF-β. Furthermore, conditional knockout of the gene encoding TGF-β receptor II from the kidney did not prevent AGE-induced renal expression of CTGF and collagen I. More specific, AGEs induced CTGF expression via the receptor for AGEs-extracellular signal–regulated kinase (RAGE-ERK)/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase–Smad cross-talk pathway because inhibition of this pathway by several methods (anti-RAGE antibody, specific inhibitors, or dominant negative adenovirus to ERK1/2 and p38) blocked this induction. Overexpressing Smad7 abolished AGE-induced Smad3 phosphorylation and CTGF expression, demonstrating the necessity for activation of Smad signaling in this process. More important, knockdown of either Smad3 or Smad2 demonstrated that Smad3 but not Smad2 is essential for CTGF induction in response to AGEs. In conclusion, AGEs induce tubular CTGF expression via the TGF-β–independent RAGE-ERK/p38-Smad3 cross-talk pathway. These data suggest that overexpression of Smad7 or targeting Smad3 may have therapeutic potential for diabetic nephropathy.

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF; CCN2), a member of CCN family of growth factors, plays an important role in connective tissue homeostasis and fibroblast proliferation, migration, adhesion, and extracellular matrix expression.1 Clinically, renal expression of CTGF is increased in patients with diabetic nephropathy (DN), and its expression correlates closely with the degree of albuminuria.2,3 In addition, studies in human renal biopsy show that CTGF expression significantly augments glomerular and tubulointerstitial injury with α-smooth muscle actin cell accumulation.4 Several pieces of evidence from recent rodent studies further support the notion that CTGF is important in the pathogenesis of DN. For example, the thickening of glomerular basement membrane is attenuated in CTGF+/− mice.5 In type 1 diabetic mouse model, cell-specific overexpression of CTGF in podocytes of CTGF transgenic mice is able to intensify proteinuria and mesangial expansion.6 The co-localization of increased renal CTGF expression and AGE accumulation in diabetic rats indicates a causal link between AGE deposition and CTGF expression.7 This is supported by the ability of the AGE inhibitor to suppress CTGF expression and reduce renal fibrosis.7 Although the mechanisms that regulate renal CTGF function are not clearly understood, CTGF should play an essential role in DN.

Engagement of AGEs to the receptor (RAGE) has been shown to play a critical role in diabetic complications, including DN.8 Indeed, AGE-induced tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and renal fibrosis are RAGE dependent.8,9 Under diabetic conditions, although treatments with high glucose and angiotensin II are also able to upregulate CTGF expression in glomerular mesangial cells (MCs) and TECs,2,10–12 it is clear that AGEs mediate CTGF expression by stimulating TGF-β expression.13,14 It is generally believed that TGF-β/Smad signaling should be responsible for inducing CTGF expression because CTGF is a downstream mediator of TGF-β signaling11,12,15–17; however, the exact mode of signaling mechanisms by which AGEs induce CTGF expression remains largely unclear.

Our previous study of MCs, TECs, and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) showed that AGEs are able to induce Smad2/3 phosphorylation markedly in TGF-β receptor I (TβRI) and TβRII mutant cell lines via the extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK)/p38 mitogen-activate protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent mechanism.18 This demonstrates a critical role for the TGF-β–independent Smad pathway in AGE-mediated fibrotic response. This is further supported by the finding that blockade of TGF-β1 with specific small hairpin RNA (shRNA) and a neutralizing antibody is unable to inhibit significantly AGE-induced CTGF mRNA expression.19 All of these studies suggest a TGF-β–independent mechanism in regulating CTGF expression in response to AGEs. Because AGEs are capable of activating the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway via the ERK/p38 MAPK-dependent mechanism and because CTGF is a target gene of TGF-β/Smad signaling,7,15,19–22 we thus hypothesized that AGEs might induce CTGF expression via the TGF-β–independent Smad3 signaling pathway. This was tested in mouse TECs lacking TGF-β1 gene23 and rat TEC lines overexpressing the dominant negative TβRII or Smad7 or having a knockdown of Smad2 or Smad3. Finally, the functional importance of the TGF-β–independent signaling pathway in AGE-mediated CTGF expression and renal fibrosis was tested in mice that had conditional knockout (KO) for TβRII from the kidney.

Results

AGEs Are Able to Induce Tubular CTGF Expression in a Time- and Dosage-Dependent Manner

It is known that AGEs are able to activate TGF-β/Smad signaling18 and TGF-β is able to induce CTGF expression.11,12,16,17 In this study, we examined whether AGEs were capable of inducing CTGF expression in TECs. As shown in Figure 1, real-time PCR demonstrated that AGEs but not control BSA induced CTGF mRNA expression in normal rat TECs (NRK52E) in a time- and dosage-dependent manner, peaking at 6 h with an optimal dosage at 33 μg/ml (Figure 1, A and B). Similarly, Western blot analysis also showed that AGEs but not control BSA induced CTGF protein expression in a time- and dosage-dependent manner, being significant at 12 h and peaking over 24 to 48 h with an optimal dosage at 33 μg/ml (Figure 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

AGEs induce CTGF expression in a time- and dosage-dependent manner in NRK52E cells. (A) Real-time PCR shows that AGEs (33 μg/ml), not BSA, induce CTGF mRNA expression in a time-dependant manner, being significant at 6 h. (B) Real-time PCR demonstrates that AGEs, not BSA, induce CTGF mRNA expression in a dosage-dependent manner, being significant at 33 μg/ml and peaking at 6 h. (C) Western blots demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) induce CTGF expression in a time-dependent manner, being significant at 12 h and peaking over 24 to 48 h. The induction of CTGF expression by AGEs is inhibited by a neutralizing RAGE antibody (anti-RAGE) but not by a control rabbit IgG antibody (Rb-IgG). (D) Western blots demonstrate that AGEs induce CTGF protein expression in a dosage-dependent manner, peaking at 33 and 66 μg/ml, which is inhibited by a neutralizing anti-RAGE antibody (10 μg/ml) but not by an isotype control Rb-IgG. BSA acts as a control in all experiments. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus either the BSA control or time 0 (or dosage 0); ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus the control antibody as indicated.

Next, we investigated whether AGEs signal through RAGE to stimulate CTGF expression. We used a neutralizing anti-RAGE antibody to block the AGE–RAGE interaction. Western blot analysis demonstrated that a neutralizing anti-RAGE antibody completely inhibited AGE-induced CTGF expression (Figure 1, C and D), demonstrating that AGEs bind the RAGE to stimulate CTGF expression.

AGEs Induce Tubular CTGF Expression via the TGF-β–Independent Smad-Signaling Pathway

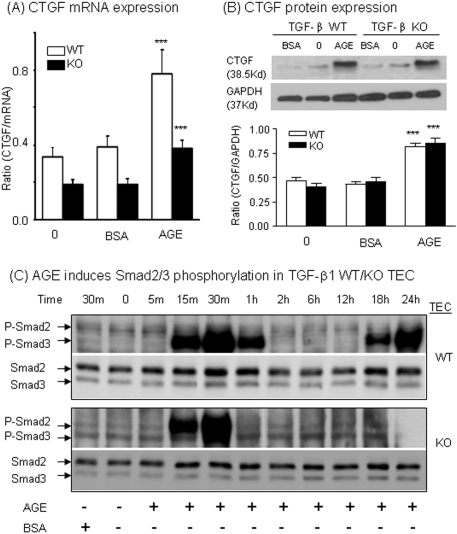

Our previous study demonstrated that AGEs are able to activate Smad signaling via both TGF-β–dependent and –independent mechanisms.18 In this study, we examined whether AGEs were capable of inducing CTGF expression in TECs via a TGF-β–independent mechanism in TGF-β1 wild-type (WT) and KO TECs.23 As shown in Figure 2, A and B, real-time PCR and Western blot analyses demonstrated that AGEs induced CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h and protein expression at 24 h in WT TECs. Interestingly, AGEs also caused a significant increase in CTGF mRNA and protein expression in TGF-β1 KO TECs (Figure 2, A and B), suggesting that AGEs may mediate CTGF expression predominantly via a TGF-β–independent pathway.

Figure 2.

AGEs induce tubular CTGF expression via the TGF-β–independent Smad signaling pathway in TGF-β1 KO TECs. (A and B) Real-time PCR (A) and Western blot analyses (B) demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not BSA control (33 μg/ml) are able to induce CTGF mRNA (at 6 h) and protein expression (at 24 h) in both TGF-β1 WT and KO TEC. (C) Western blots demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not control BSA (33 μg/ml) induce phosphorylation of Smad3 in WT TECs with two peaks (15 to 30 min and 18 to 24 h), whereas only an early Smad3 phosphorylation (15 to 30 min) is detected in TGF-β KO TECs after AGE stimulation. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 versus time 0 and BSA control.

We then examined signaling mechanisms by which AGEs induce CTGF expression. Western blot analysis revealed that AGEs rapidly increased Smad2/3 phosphorylation, presumably the phosphorylated Smad3, at 15 to 30 min in both TGF-β1 WT and KO TECs (Figure 2C). Interestingly, a second peak of Smad2/3 phosphorylation induced by AGEs at 18 to 24 h was found only in TGF-β1 WT but not in KO TECs (Figure 2C). This was associated with upregulation of endogenous TGF-β1 at 24 h in WT but not in KO TECs (data not shown).

To confirm the TGF-β–independent pathway in AGE-induced CTGF expression, we generated a NRK52E cell line stably expressing dominant negative TβRII. In this stable cell line, mRNA transcript of dominant negative TβRII was highly expressed (Figure 3A), and, thus TGF-β1–induced CTGF expression was blocked (Figure 3C), verifying the impaired TGF-β signaling pathway in these cells; however, NRK52E cells overexpressing dominant negative TβRII did not alter the levels of AGE-induced CTGF mRNA and protein expression when compared with normal NRK52E cells (Figure 3, B and C). Interestingly, although addition of AGEs was able to induce both the early and the late activation of Smad2/3 in normal NRK52E cells, AGEs induced only the early activation of Smad2/3 at 5 to 30 min but not the late Smad2/3 phosphorylation at 18 to 24 h in the stable TEC line expressing dominant negative TβRII (Figure 3D). These results demonstrated that the early TGF-β–independent Smad pathway is critical in AGE-induced CTGF expression.

Figure 3.

AGEs induce tubular CTGF expression via the TGF-β–independent Smad signaling pathway in NRK52E cell lines overexpressing dominant negative TβRII. (A) RT-PCR demonstrates that the mRNA of dominant negative TβRII is stably expressed in two NRK52E cell lines transfected with dominant negative TβRII but absent in normal NRK52E cells. P, positive PCR control of dominant negative TβRII vector; N, negative PCR control without expression vector. (B) Real-time PCR analyses demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not BSA control (33 μg/ml) are able to induce CTGF mRNA expression (at 6 h) in both normal NRK52E cells and NRK52E cells with overexpression of dominant negative TβRII. (C) Western blot analyses demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not BSA control (33 μg/ml) are able to induce CTGF protein expression (at 24 h) in both normal NRK52E cells and NRK52E cells with overexpression of dominant negative TβRII. Note that addition of TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) is able to induce CTGF expression in normal NRK52E but is absent in NRK52E cells overexpressing dominant negative TβRII. (D) Western blots demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not control BSA (33 μg/ml) induce phosphorylation of Smad3 in normal NRK52E with two peaks (15 to 30 min and 18 to 24 h), whereas only an early Smad3 phosphorylation (15 to 30 min) is detected in NRK52E cells with overexpression of dominant negative TβRII after AGE stimulation. Note that TGF-β1–induced (2.5 ng/ml) phosphorylation of Smad2/3, presumably Smad3, is present in normal NRK52E but absent in NRK52E cells overexpressing dominant negative TβRII. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus time 0 and BSA control; ###P < 0.001 versus AGE-treated TECs.

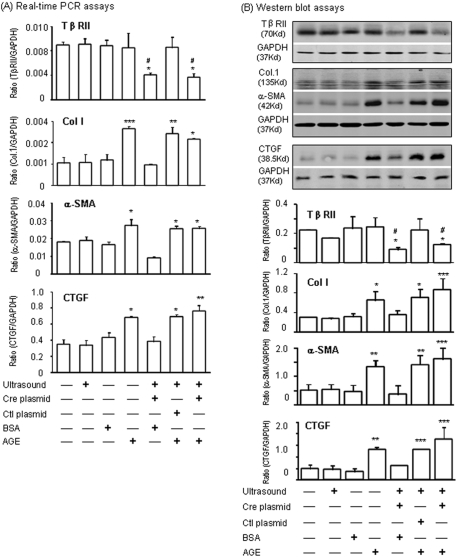

To verify further the functional importance of the TGF-β–independent pathway in AGE-induced CTGF expression in vivo, we generated kidney-specific TβRII conditional KO mice using an ultrasound-microbubble Cre technique. As detected by PCR (Figure 4A), immunohistochemistry (Figure 4B), real-time PCR (Figure 5A), and Western blot analysis (Figure 5B), >70% of the floxed TβRII genes were nonselectively deleted from the kidney of TβRIIflox/flox mice. Interestingly, deletion of TβRII gene from the kidney did not prevent AGE-induced CTGF and collagen I expression (Figures 4 and 5). Although infusion of AGEs resulted in upregulation of renal CTGF and collagen I (Figures 4C and 5, A and B), microalbuminuria did not occur in mice with or without conditional deletion of TβRII when compared with normal or control mice with BSA infusion (2.794 ± 0.473 μg/ml in AGEs versus 2.670 ± 0.341 μg/ml in BSA). Findings from in vivo studies further demonstrated AGE-mediated CTGF expression was TGF-β independent.

Figure 4.

Effect of conditional deletion of TβRII on AGE-induced renal CTGF and collagen I expression in a mouse model of AGE infusion by immunohistochemistry. (A) PCR shows that ultrasound-mediated Cre-recombinase plasmid (255 bp) is able to delete approximately 70% of the floxed TβRII (575 bp) from the kidney when compared with the deleted allele (692 bp). (B) Immunohistochemistry shows that ultrasound-mediated Cre/lox recombination results in a substantial deletion of TβRII from the kidney cells in the glomerulus and tubulointerstitium. (C) Immunohistochemistry reveals that in contrast to treatment with BSA alone, ultrasound-microbubble alone, and BSA + ultrasound + control plasmid, AGE infusion is able to upregulate renal CTGF and collagen I expression. Deletion of renal TβRII gene by ultrasound-mediated Cre/lox recombination in kidney does not alter AGE-induced renal CTGF and collagen I expression. Results represent groups of three mice. Magnification, ×400.

Figure 5.

Effect of conditional deletion of TβRII on AGE-induced renal CTGF and collagen I expression in a mouse model of AGE infusion by real-time PCR and Western blot analyses. (A and B) Real-time PCR (A) and Western blot (B) analyses show that whereas ultrasound-mediated Cre/lox recombination deletes TβRII gene expression from kidney, deletion of TβRII gene does not prevent AGE-induced expression of renal CTGF and fibrotic markers, such as collagen I and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) mRNA and protein expression. Data represent groups of three mice. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus normal mice; #P < 0.05 versus mice with AGE infusion alone without ultrasound treatment.

RAGE-Mediated Activation of the ERK/p38 MAPK-Smad Cross-Talk Pathway is Necessary for AGE-Induced Tubular CTGF Expression

Next, we examined the signaling mechanism of AGE-activated Smad3 independent of TGF-β in TGF-β1 KO TECs. As shown in Figure 6, addition of AGEs upregulated both ERK1/2 and p38 phosphorylation with two peaks (15 to 30 min and 18 to 24 h) in TGF-β1 WT TECs, but only an early phosphorylation peak (15 to 30 min) of ERK1/2 and p38 occurred in TGF-β1 KO TECs, suggesting the early activation of ERK/p38 was TGF-β1 independent. These results were also paralleled with the finding of AGE-induced Smad3 phosphorylation when TGF-β signaling was impaired, as shown in Figures 2C and 3D.

Figure 6.

AGEs induce an early phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK via the TGF-β–independent Smad signaling pathway. (A) ERK1/2 phosphorylation. (B) p38 phosphorylation. Western blots demonstrate that AGEs (33 μg/ml) but not control BSA (33 μg/ml) induce phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38 in TGF-β1 WT TECs with two peaks (30 min and 18 h). In contrast, in TGF-β1 KO TECs, AGEs induce only an early phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and p38. Data are means ± SEM for at least 3 independent experiments.

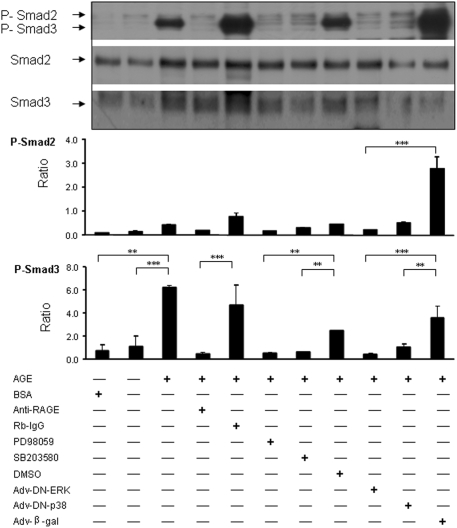

To investigate the relationship between phosphorylation of ERK/p38 MAPKs and activation of Smad3, we examined whether the engagement of AGEs to the RAGE mediated Smad signaling directly via the MAPK-Smad cross-talk pathway. We first demonstrated that AGE-activated Smad3 in TGF-β1 KO TECs was RAGE dependent because an addition of the anti-RAGE antibody but not the control isotype rabbit IgG blocked AGE-induced Smad3 phosphorylation (Figure 7). We then examined the functional activities of ERK1/2 and p38 in activating Smad3. Again, addition of ERK1/2 inhibitor (PD98059; 10 μM) and p38 inhibitor (SB203580; 10 μM) suppressed AGE-induced Smad3 phosphorylation, respectively (Figure 7). More specific, infections of adenovirus with dominant negative ERK1/2 and p38 also suppressed AGE-induced Smad3 phosphorylation (Figure 7). Thus, RAGE-mediated activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs is necessary for Smad3 activation.

Figure 7.

AGEs induce Smad3 activation via the RAGE-mediated, ERK/p38 MAPK mechanism. A representative Western blot shows that AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) rapid Smad3 phosphorylation in TGF-β1 KO TECs at 30 min is blocked by a rabbit neutralizing RAGE antibody (anti-RAGE; 10 μg/ml) and by both ERK1/2 (PD98059; 10 μM) and p38 MAPK (SB203580; 10 μM) inhibitors, respectively. This is further confirmed by infecting cells with dominant negative ERK (Adv-DN-ERK) and p38 (Adv-DN-p38) adenovirus. BSA (33 μg/ml), normal rabbit IgG (Rb-IgG; 10 μg/ml), solvent DMSO, and adenovirus β-galactosidase (Adv-β-Gal) acted as negative controls. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control as indicated.

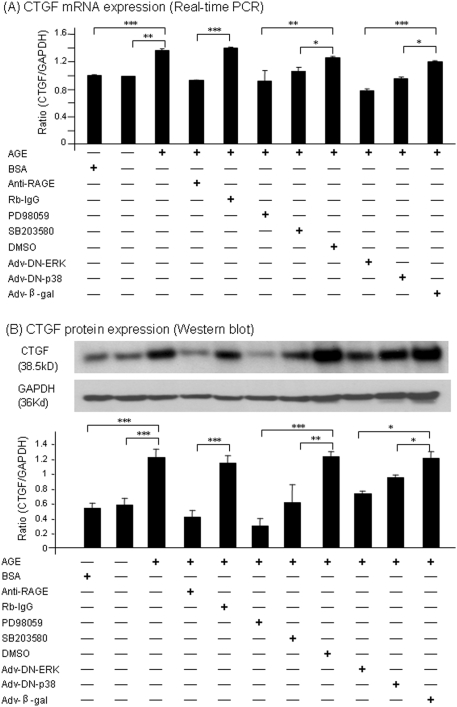

We also examined the functional role of the TGF-β–independent RAGE-ERK/p38-Smad pathway in AGE-induced CTGF expression in TGF-β1 KO TECs. As shown in Figure 8, real-time PCR and Western blot analyses demonstrated that AGE-induced CTGF mRNA (at 6 h) and protein (24 h) expression was blocked by a neutralizing RAGE antibody, pharmaceutical inhibitors to ERK1/2 (PD98059) and p38 (SB203580), and dominant negative ERK1/2 and p38 adenovirus. These results suggest that RAGE-mediated activation of the ERK/p38 MAPK-Smad2/3 cross-talk pathway is essential for AGE-induced tubular CTGF expression.

Figure 8.

AGEs induce CTGF expression via the RAGE-mediated, ERK/p38 MAPK mechanism. (A) Real-time PCR. (B) Western blot analysis. Results show that AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) but not BSA-induced (33 μg/ml) CTGF mRNA at 6 h and protein expression at 24 h in TGF-β1 KO TECs are blocked by a rabbit neutralizing RAGE antibody (anti-RAGE; 10 μg/ml) and by inhibitors to ERK1/2 (PD98059; 10 μM) and p38 (SB203580; 10 μM). Similar inhibitions were also observed when the cells were infected with dominant negative ERK1/2 (Adv-DN-ERK) or p38 (Adv-DN-p38) adenovirus. BSA (33 μg/ml), normal rabbit IgG (Rb-IgG; 10 μg/ml), solvent DMSO, and adenovirus β-galactosidase (Adv-β-Gal) were used as negative controls. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control as indicated.

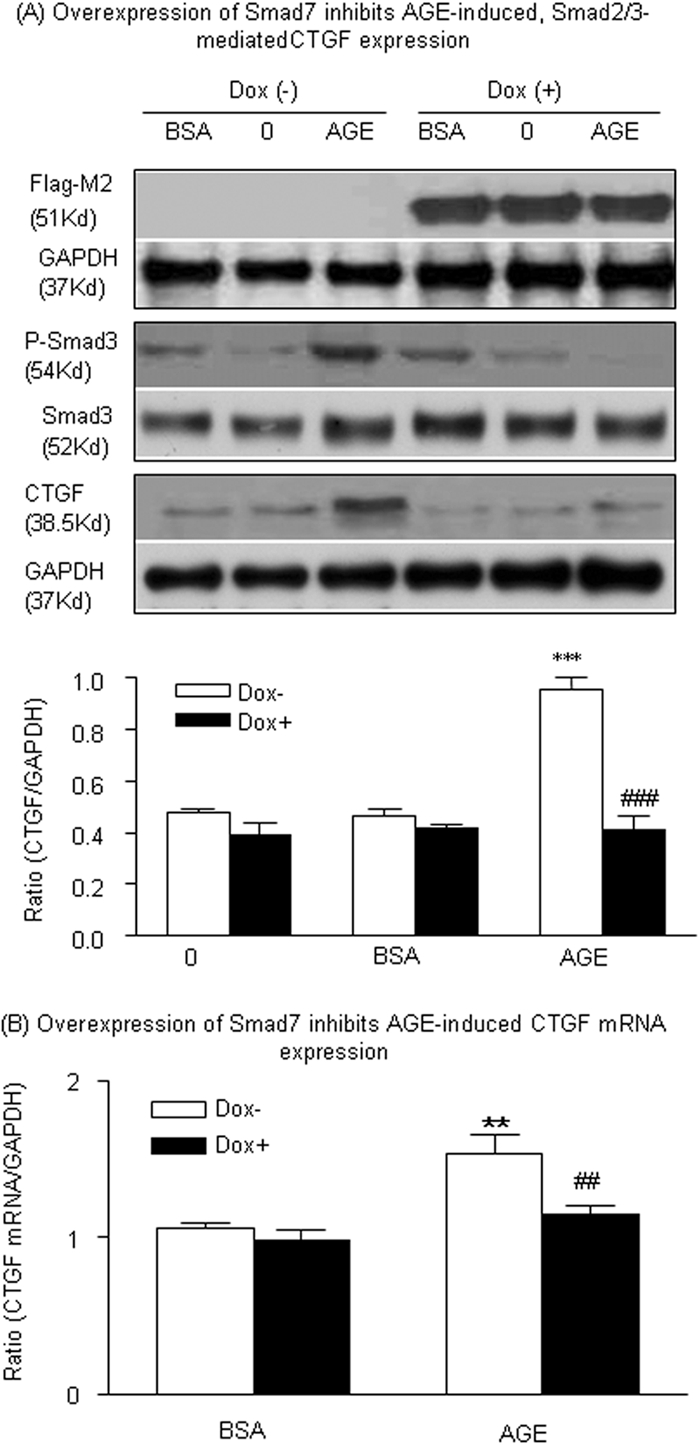

Finally, to investigate whether the Smad signaling pathway was important for induction of CTGF expression by AGEs, we overexpressed Smad7 in a stable, Dox-regulated Flag-M2-Smad7–expressing NRK52E TEC line.23 As shown in Figure 9A, an addition of Dox (2 μg/ml) induced Flag-M2-Smad7 transgene expression, as identified by the anti–Flag-M2 antibody. Overexpression of Smad7 resulted in a suppression of Smad3 phosphorylation at 30 min in response to AGEs, and this suppression was associated with an abrogation of CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h and protein expression at 24 h (Figure 9), delineating a negative regulating role for Smad7 and the essential role for Smad signaling in AGE-mediated CTGF expression.

Figure 9.

Overexpression of Smad7 inhibits AGE-induced, Smad3-mediated CTGF expression in TECs. (A) Representative Western blots show that addition of Dox (2 μg/ml) induces Smad7 transgene expression in a stable, Dox-regulated Flag-M2-Smad7–expressing TEC line (NRK52E) as determined by the anti–Flag-M2 antibody. Dox-induced overexpression of Flag-M2-Smad7 blocks AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) Smad3 phosphorylation at 30 min and CTGF expression at 24 h. (B) Real-time PCR analysis reveals that overexpression of Smad7 induced by Dox inhibits AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for at least three independent experiments. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus time 0 or control BSA (33 μg/ml) treatment; ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 versus AGE-treated TECs without Dox.

Smad3 but not Smad2 Is a Key Mediator of AGE-Induced Tubular CTGF Expression

We next dissected the specific roles of Smad2 and Smad3 in AGE-induced CTGF expression in NRK52E TEC cell lines in which Smad2 and Smad3 expressions were knocked down by small interfering RNA technique, as described in the Concise Methods section. As shown in Figure 10, real-time PCR and Western Blot analyses showed that NRK52E TECs stably expressed shRNA-Smad2 or shRNA-Smad3 markedly and specifically reduced Smad2 or Smad3 mRNA individually. A significant inhibition of AGE-induced CTGF mRNA and protein expression was found in Smad3 knockdown TECs (Figure 10). In contrast, knockdown of Smad2 produced no effect on AGE-induced CTGF expression at both mRNA and protein levels (Figure 10), suggesting Smad3 but not Smad2 mediates CTGF expression under diabetic condition.

Figure 10.

AGE-induced tubular CTGF expression is Smad3 dependent but Smad2 independent. (A) Real-time PCR analysis demonstrates that Smad2 or Smad3 is specifically knocked down (KD) in the stable TEC cell line expressing either Smad2 or Smad3 shRNA individually; however, knockdown of Smad3 but not Smad2 blocks AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h. *P < 0.05 versus 0 h; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus WT cells. (B) Western blot analysis demonstrates that Smad2 or Smad3 is specifically knocked down (KD) in the stable TEC cell line expressing either Smad2 or Smad3 shRNA individually. Western blot analysis also shows that knockdown of Smad3 but not Smad2 blocks AGE-induced (33 μg/ml) CTGF protein expression at 24 h. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM for four independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus BSA (33 μg/ml); ###P < 0.001 versus AGE-treated WT cells.

Discussion

It is now well accepted that AGEs are key mediators in DN.24 AGEs are able to mediate diabetic complications by stimulating a number of mediators, including oxygen free radicals, cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, TGF-β1, and CTGF.25 The induction of TGF-β1 emerges to be the key intermediate step for many AGE–RAGE-mediated effects on cell growth and matrix homeostasis.24 Accumulation of AGEs closely correlates to TGF-β1 expression in the kidney, and inhibitors to AGEs reduce overproduction of TGF-β1 in diabetic animals independent of the glycemic status.14,26 In addition, neutralizing antibodies to TGF-β1 are able to block AGE-induced EMT.27 All of these studies suggest a critical role for TGF-β in AGE-mediated diabetic complications.

CTGF has been demonstrated to act as a downstream mediator of the cellular effect of TGF-β1 in many cell types.11,12,16,17 In general, TGF-β1 signals through a heteromeric receptor complex of the type I and type II receptors to activate the downstream intracellular mediators Smad2 and Smad3 by phosphorylation.28,29 Phosphorylated Smad2/3 will then activate TGF-β–responsive genes, of which CTGF is one.7,15,19–22 Indeed, functional TGF-β–responsive element and Smad-binding element are found in the CTGF promoter, suggesting that the TGF-β/Smad signaling should be greatly responsible for CTGF expression.15,30–32 Because AGEs are able to induce TGF-β1 expression, it is generally believable that AGE-induced CTGF expression via the TGF-β–dependent Smad signaling pathway.

In addition, a significant finding in this study was that AGEs could directly induce CTGF expression through a TGF-β–independent, Smad-dependent signaling pathway that was mediated by the RAGE-ERK/p38 MAPK mechanism. This was supported by the findings that AGEs were able to stimulate a rapid phosphorylation of Smad2/3, ERK1/2, and p38 at 15 to 30 min and CTGF expression in TECs lacking TGF-β1 gene or overexpressing dominant negative TβRII, which was blocked by a neutralizing antibody to RAGE and by pharmacologic inhibitors or dominant negative adenovirus to ERK1/2 or p38. These results were consistent with our previous findings that AGEs activate Smad signaling via a TGF-β–independent mechanism in MCs, TECs, and VSMCs and induce EMT through the RAGE-ERK1/2 MAPK pathway.9,18 Results from other studies in MCs also support this notion that blockade of high glucose–induced CTGF expression in MCs by an anti–TGF-β1 antibody or knockdown of TGF-β1 mRNA do not reduce AGE-induced CTGF mRNA expression, although TGF-β1–induced CTGF expression is blocked.19 Taken together, this study provided new evidence that induction of CTGF expression by AGEs may be predominantly via a TGF-β–independent, Smad-dependent pathway. Conditional deletion of TβRII from the kidney did not prevent renal CTGF expression and fibrotic changes in the kidney after a 7-d AGE infusion further demonstrated a functional importance of the TGF-β–independent pathway in AGE-mediated diabetic kidney injury.

A critical role of Smad signaling in AGE-induced CTGF expression was further confirmed by the ability of overexpressing Smad7 to inhibit AGE-induced Smad2/3 phosphorylation and CTGF expression. Indeed, overexpression of Smad7 was capable of inhibiting the early activation of Smad2/3 at 30 min in response to AGEs, thereby blocking AGE-induced CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h and protein expression at 24 h. In MCs, transfection of Smad7 decreases both basal and TGF-β–induced CTGF expression,21 suggesting that Smad7 plays a negative regulating role in AGE-induced CTGF expression and that Smad-dependent TGF-β signaling is necessary for CTGF production in response to AGEs. Because it is not until 24 h that AGEs stimulate TGF-β1 production in NRK52E TECs as determined by both real-time PCR and ELISA,2,20 blockade of Smad2/3 phosphorylation at 30 min and CTGF mRNA expression at 6 h and protein expression at 24 h could be TGF-β independent.

Finally, we also found that AGE-induced tubular CTGF expression was mediated by Smad3, not Smad2, because knockdown of Smad3, not Smad2, blocked the early CTGF mRNA and protein expression after AGE stimulation. This may be associated with a directly regulating role of Smad3 in CTGF expression, because Smad3-binding elements are found in the CTGF promoters.15,30 A critical role for Smad3 in TGF-β1–induced CTGF expression has been reported by the findings that TGF-β1–induced CTGF mRNA expression is significantly reduced in the fibroblast derived from Smad3 knockout mice,15,33 in TECs with knockdown for Smad3,20 in fibroblasts by expressing dominant negative Smad3,22 and in diabetic glomerulopathy in mice lacking Smad3.34,35 This study added new information that Smad3, not Smad2, plays a critical role in AGE-induced tubular CTGF expression.

It has been proposed that AGEs contribute to the age-related decline in the tissues in normal aging.36 Recent progress in the understanding of biologic effects of AGEs shows that AGEs accumulate in vascular tissues with normal aging and at an accelerated rate in diabetes and renal failure.37,38 AGEs are normally cleared by the kidney but accumulate in plasma in patients with DN.39 In experimental animals, an inhibition of AGE accumulation protects against cardiovascular and renal aging.37 Glycemic control also delays accumulation of AGE to reduce renal aging38; however, the exact mechanism as to how AGEs relate to aging is still unknown. Results from this study add new evidence that AGEs may stimulate CTGF expression to induce renal deterioration under the diabetic conditions or promote renal aging under the physiologic process.

In conclusion, AGEs are able to induce tubular CTGF expression via the TGF-β–independent Smad3 pathway (Figure 11). This induction is RAGE dependent and requires activation of Smad3 through the ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK pathway. Taken together with the previous findings, targeting the RAGE and/or the Smad3 signaling pathway may offer novel therapeutic strategies for curing diabetic complications.

Figure 11.

A schematic diagram of AGE-induced CTGF expression is shown. Engagement of RAGE by AGEs activates Smad signaling via both the ERK/p38 MAPK-Smad signaling cross-talk pathway (TGF-β–independent pathway) and the classic TGF-β signaling pathway (TGF-β–dependent pathway) to induce CTGF expression.

Concise Methods

Reagents

DMEM and FBS were obtained from Hyclone (Logan, UT). AGE-BSA (A8426), BSA (A4919), anti-RAGE antibodies (cat. no. R5278), and doxycycline (Dox) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The ERK1/2 kinase inhibitor PD98059 and the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Recombinant adenovirus construct containing bacterial β-galactosidase gene (Adv-β-gal), dominant negative ERK1/2, or p38 were a gift from Dr. Shokei Kim-Mitsuyama (Kamamoto University, Kamamoto, Japan) as described previously.40,41 All preparations of AGE-BSA and its dilutions were performed under endotoxin-free conditions and were passed over an endotoxin-binding affinity polymyxin column (Detoxi-gel; Pierce, Rockford, IL).18 Before in vitro study, reagents were examined for endotoxin levels by the Limulus amebocyte assay (EToxate; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) with endotoxin levels <0.2 ng/ml.

Cell Culture

The NRK52E normal rat tubular epithelial cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained in DMEM/LG supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). To impair TGF-β signaling, we developed a stable dominant negative TβRII-expressing NRK52E cell line. A dominant negative TβRII (a gift from Dr. Derynck) plasmid was transfected into NRK52E by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and then subjected to G418 selection (500 μg/ml). The expression of dominant negative TβRII was determined by reverse transcriptase–PCR (RT-PCR). Cells with stable expression dominant negative TβRII were cultured with AGE-BSA or control BSA for detection of CTGF protein and phosphorylation of Smad2/3 by Western blot analysis. TGF-β1 (2.5 ng/ml) was used as positive control.

To investigate whether AGE-induced CTGF expression was TGF-β dependent, we cultured TECs isolated from the kidneys of TGF-β1 WT or TGF-β1 KO mice in AGE-BSA and BSA at a dosage of 33 μg/ml for 0, 5, 15, 30, and 60 min and 2, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h for detecting phosphorylation of Smad2/3 (phospho-Smad2/3), phospho-ERK1/2, phospho-p38 MAPK, CTGF mRNA by real-time PCR, and CTGF protein expression by Western blot analysis. Isolation and characterization of TGF-β1 KO TECs were described previously.23

To investigate the negative regulating role of Smad7 in AGE-induced activation of Smad2/3 and CTGF expression, we used a stable, Dox-regulated Smad7-expressing NRK52E cell line.3,42 To induce Smad7 transgene expression, we treated cells with Dox at an optimal concentration (2 μg/ml) for 24 h.

To dissect further the specific role of Smad2 and Smad3 in AGE-induced CTGF expression, we generated stable cell lines with Smad2 and Smad3 gene knockdown. The gene-specific insert sequences for Smad 2 (sense ATT CTT ACC CTT GGT AAG A and antisense TCT TAC CAA GGG TAA GAA T) and Smad3 (sense GCA CCC TCC AAT GTG ATA A and antisense TTA TCA CAT TGG AGG GTG C) were separated by a nine-nucleotide noncomplementary spacer (TC TCT TGA A), synthesized, and subsequently subcloned into the BglII and HindIII sites of the pSuper-green fluorescence protein (GFP)/Neo vector (OligoEngine, Seattle, WA) to generate pSuper-Smad RNA interference constructs. The vector allows direct synthesis of shRNA transcripts using the polymerase H1-RNA gene promoter and coexpresses GFP to allow detection of transfected cells. A small interfering RNA with no predicted target site in the rat genome was inserted into pSUPER-GFP/Neo and served as a negative control. The pSuper plasmids were then transfected into NRK52E by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and then subjected to G418 selection (500 μg/ml). The expression of Smad2 and Smad3 was determined by immunoblotting and real-time PCR, and cells with Smad2 or Smad3 knockdown were cultured with AGE-BSA or control BSA for detection of CTGF mRNA and protein by real-time PCR and Western blot analysis.

NRK52E cells were grown in DMEM/LG containing 0.5% FBS in six-well plastic plates at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with AGE-BSA or BSA control at concentrations of 0, 10, 33, and 66 μg/ml for periods of 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h for CTGF detection.

To block the binding of AGEs to RAGE, we used a neutralizing anti-RAGE antibody (10 μg/ml)27 and added a species-specific isotype control normal rabbit IgG (10 μg/ml; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) to the cells 30 min before AGE stimulations and cultured it for periods as described previously to block AGE activity.18 To inhibit AGE-induced ERK1/2 MAPK or p38 MAPK activities, we used inhibitors to ERK1/2 (PD98059; 10 μM) or p38 (SB203580; 10 μM) MAPKs and Adv–dominant negative ERK or Adv–dominant negative p38 adenovirus, respectively. Adv-β-gal was used as a negative control. The characterization and transfection of these dominant negative vectors and negative control have been described elsewhere.40,41 Briefly, following the established protocol,43 TECs were incubated with the adenovirus at multiplicity of infection of 50 in DMEM for 1 h and then made quiescent for 24 h before stimulation with AGEs.

Cre-Expressing Plasmid Construction

The Cre-expressing plasmid (a gift from Dr. Kazuhiro Oka; Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) was constructed as the following: The Cre-Nuc (Cre containing nuclear localization signal at the N-terminus) cDNA was generated by PCR using pBS185 (Invitrogen) as a template. The following PCR primers were used: 5′-GAG AAG CTT AGA TCT CCA CCA TGG CTC CCA AGA AGA AGA GGA AGT GAT GTC CAA TTT ACT GAC CGT ACA C-3′ and 5′-GAC GTG TGC GGC CGC CTA ATC GCC ATC TTC CAG CAG-3′. The italicized nucleotides are artificial cloning sites. The resulting cDNA was verified by sequencing analysis, excised by BglII and NotI digestion, and then subcloned into the BamHI and NotI of pBOS vector containing elongation factor 1 promoter and rabbit β-globin polyA.

Generation of Kidney-Specific Conditional TβRII Knockout Mice Using Ultrasound-Mediated Cre/lox Recombination

Because TβRII null mutant mice are embryonic lethal,44 we used the Cre/lox recombination method to generate kidney-specific TβRII KO mice. Five-week-old TβRIIflox/flox mice (provided by Drs. Stefan Karlsson and Per Levéen, Lund University, Lund, Sweden)45 were used to generate kidney-specific conditional TβRII KO mice by using an ultrasound-mediated delivery system as described in our previous studies.46,47 The mixture of Cre-recombinase plasmid or empty vector (100 μg) in 150 μl of PBS with Sonovue (echocardiographic contrast microbubble; Bracco s.p.a., Milan, Italy) in 1:1 vol/vol ratio was transferred into the kidney via the tail vein followed by applying a ultrasound transducer (Sonoplus 590, 1 MHz; Ernaf-Nonius, Delft, Netherlands) directly on the skin over the renal area for 5 min to mediate Cre delivery into the kidney. Expression of Cre-recombinase in kidney was identified by PCR with the following primers: Cre-1 5′-AGG TTC GTG CAC TCA TGG A-3′ and Cre-2 5′-TCG ACC AGT TTA GTT ACC C-3′. These primers will yield in a 255-bp product. Deletion of TβRII gene from the kidney was determined by PCR with primers for the detection of floxed-TβRII allele: Bam Down 5′-TAT GGA CTG GCT GCT TTT GTA TTC-3′, Bam Up 5′-TGG GGA TAG AGG TAG AAA GAC ATA, and Kpn Up 5′-TAT TGG GTG TGG TTG TGG ACT TTA-3′. These primers result in a 692-bp product from the deleted allele, whereas the WT allele produces a 575-bp product.

Deletion of TβRII gene was further confirmed by examining expression levels of TβRII in kidneys with real-time RT-PCR, Western blot analyses, and immunohistochemistry. All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Experimental Ethics Committee, the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

AGE Infusion of Mice

Groups of three mice were infused with AGE-BSA or BSA at 10 mg/kg per d (Sigma) daily for 7 consecutive days via intraperitoneal injection48 and were treated with or without ultrasound and with or without Cre or control plasmids. After 7 d of AGE infusion, mice were killed and kidneys were harvested for analyses.

Cell RNA Extraction, RT-PCR, and Real-Time PCR Examination

Total RNA was isolated from the cultured cells and kidney tissues using the RNAeasy Isolation Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Template cDNA was prepared using reverse transcriptase. RT-PCR detection was used to determine the expression of dominant negative TβRII. PCR was performed using primers to the FLAG epitope sequence: ATC GTC ATC GTC TTT GTA GTC and human TβRII TCC CAC CGC ACG TTC AGA AG. These primers result in 500-bp products. cDNA was amplified for 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 45 s, and elongation for 2 min at 72°C in reaction buffer containing 2 mM MgCl2, 1× PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen), and 0.2 μM of each primer as described previously.49

Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described previously.50 Briefly, a real-time PCR was performed using Bio-Rad iQ SYBR Green supermix with Opticon2 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed and subjected to PCR as follows: 94°C for 2 min followed by 50 cycles at 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The primers used in this study were as follows: CTGF forward 5′-CTC CTA CTA CGA GCT GAA CCA G and reverse 5′-CCA GAA AGC TCA AAC TTG ACA GGC and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) forward 5′-GCA TGG CCT TCC GTG TTC and reverse 5′-GAT GTC ATC ATA CTT GGC AGG TTT. Reaction specificity was confirmed by melting curve analysis. Housekeeping gene GAPDH was used as an internal standard. Ratios for mRNA/GAPDH mRNA were calculated using the ΔΔCt method (2−ΔΔCt) for each sample and expressed as the mean ± SEM.

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously,42 with primary antibodies against CTGF and M2-Flag antibody (Sigma); ERK1/2, p38, phosphorylated ERK1/2, and phosphorylated p38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); Smad2 (Zymed-Invitrogen); Smad3 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY); phospho-Smad2/3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; or Cell Signaling Technology [Danvers, MA]); and GAPDH (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). After being washed extensively, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody or an IRDyeTM800-conjugated secondary antibody (Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA) for 1 h at room temperature in 1% BSA/TBST. The signals were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) or by the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (San Diego, CA). For each sample, protein levels were determined by densitometry scanning of bands using the Image J software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) and normalizing to GAPDH levels.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed in paraffin sections using a microwaved-based antigen retrieval technique.51,52 The antibodies used in this study included rabbit polyclonal antibodies to TβRII (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), collagen I (Southern Tech, Birmingham, AL), and GAPDH (Sigma). An isotype-matched rabbit IgG (Sigma) was used as negative controls throughout the study.

Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was repeated at least three times throughout the study. Data from real-time PCR and Western blot analysis were expressed as means ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls comparison program from GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (RGC GRF 768207 and 767508 to H.Y.L. and 763908 to A.C.C.), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Intramural Research Program (to J.B.K.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

References

- 1.Twigg SM, Cooper ME: The time has come to target connective tissue growth factor in diabetic complications. Diabetologia 47: 965–968, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twigg SM, Cao Z, McClennan SV, Burns WC, Brammar G, Forbes JM, Cooper ME: Renal connective tissue growth factor induction in experimental diabetes is prevented by aminoguanidine. Endocrinology 143: 4907–4915, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert RE, Akdeniz A, Weitz S, Usinger WR, Molineaux C, Jones SE, Langham RG, Jerums G: Urinary connective tissue growth factor excretion in patients with type 1 diabetes and nephropathy. Diabetes Care 26: 2632–2636, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta S, Clarkson MR, Duggan J, Brady HR: Connective tissue growth factor: Potential role in glomerulosclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Kidney Int 58: 1389–1399, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nieuwenhoven FA, Jensen LJ, Flyvbjerg A, Goldschmeding R: Imbalance of growth factor signalling in diabetic kidney disease: Is connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, CCN2) the perfect intervention point? Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 6–10, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokoi H, Mukoyama M, Mori K, Kasahara M, Suganami T, Sawai K, Yoshioka T, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Kuwabara T, Sugawara A, Nakao K: Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor in podocytes worsens diabetic nephropathy in mice. Kidney Int 73: 446–455, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burns WC, Twigg SM, Forbes JM, Pete J, Tikellis C, Thallas-Bonke V, Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P: Connective tissue growth factor plays an important role in advanced glycation end product-induced tubular epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition: Implications for diabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2484–2494, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM: Mechanisms of disease: Advanced glycation end-products and their receptor in inflammation and diabetes complications. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4: 285–293, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li JH, Wang W, Huang XR, Oldfield M, Schmidt AM, Cooper ME, Lan HY: Advanced glycation end products induce tubular epithelial-myofibroblast transition through the RAGE-ERK1/2 MAP kinase signaling pathway. Am J Pathol 164: 1389–1397, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi W, Twigg S, Chen X, Polhill TS, Poronnik P, Gilbert RE, Pollock CA: Integrated actions of transforming growth factor-beta1 and connective tissue growth factor in renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F800–F809, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahab NA, Yevdokimova N, Weston BS, Roberts T, Li XJ, Brinkman H, Mason RM: Role of connective tissue growth factor in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Biochem J 359: 77–87, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riser BL, Denichilo M, Cortes P, Baker C, Grondin JM, Yee J, Narins RG: Regulation of connective tissue growth factor activity in cultured rat mesangial cells and its expression in experimental diabetic glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 25–38, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang G, Schinzel R, Simm A, Sebekova K, Heidland A: Advanced glycation end products impair protein turnover in LLC-PK1: Amelioration by trypsin. Kidney Int Suppl 78: S53–S57, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Okamoto T, Amano S, Koga K, Takeuchi M: Advanced glycation end products inhibit de novo protein synthesis and induce TGF-beta overexpression in proximal tubular cells. Kidney Int 63: 464–473, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes A, Abraham DJ, Sa S, Shiwen X, Black CM, Leask A: CTGF and SMADs, maintenance of scleroderma phenotype is independent of SMAD signaling. J Biol Chem 276: 10594–10601, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twigg SM, Joly AH, Chen MM, Tsubaki J, Kim HS, Hwa V, Oh Y, Rosenfeld RG: Connective tissue growth factor/IGF-binding protein-related protein-2 is a mediator in the induction of fibronectin by advanced glycosylation end-products in human dermal fibroblasts. Endocrinology 143: 1260–1269, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Makino H, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Mori K, Suganami T, Yahata K, Fujinaga Y, Yokoi H, Tanaka I, Nakao K: Roles of connective tissue growth factor and prostanoids in early streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat kidney: The effect of aspirin treatment. Clin Exp Nephrol 7: 33–40, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li JH, Huang XR, Zhu HJ, Oldfield M, Cooper M, Truong LD, Johnson RJ, Lan HY: Advanced glycation end products activate Smad signaling via TGF-beta-dependent and independent mechanisms: Implications for diabetic renal and vascular disease. FASEB J 18: 176–178, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou G, Li C, Cai L: Advanced glycation end-products induce connective tissue growth factor-mediated renal fibrosis predominantly through transforming growth factor beta-independent pathway. Am J Pathol 165: 2033–2043, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phanish MK, Wahab NA, Colville-Nash P, Hendry BM, Dockrell ME: The differential role of Smad2 and Smad3 in the regulation of pro-fibrotic TGFbeta1 responses in human proximal-tubule epithelial cells. Biochem J 393: 601–607, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phanish MK, Wahab NA, Hendry BM, Dockrell ME: TGF-beta1-induced connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) expression in human renal proximal tubule epithelial cells requires Ras/MEK/ERK and Smad signalling. Nephron Exp Nephrol 100: e156–e165, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leivonen SK, Hakkinen L, Liu D, Kahari VM: Smad3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 coordinately mediate transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of connective tissue growth factor in human fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 124: 1162–1169, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grande JP, Warner GM, Walker HJ, Yusufi AN, Cheng J, Gray CE, Kopp JB, Nath KA: TGF-beta1 is an autocrine mediator of renal tubular epithelial cell growth and collagen IV production. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 227: 171–181, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas MC, Forbes JM, Cooper ME: Advanced glycation end products and diabetic nephropathy. Am J Ther 12: 562–572, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forbes JM, Cooper ME, Oldfield MD, Thomas MC: Role of advanced glycation end products in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 14[ Suppl 3]: S254–S258, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osicka TM, Yu Y, Panagiotopoulos S, Clavant SP, Kiriazis Z, Pike RN, Pratt LM, Russo LM, Kemp BE, Comper WD, Jerums G: Prevention of albuminuria by aminoguanidine or ramipril in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats is associated with the normalization of glomerular protein kinase C. Diabetes 49: 87–93, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oldfield MD, Bach LA, Forbes JM, Nikolic-Paterson D, McRobert A, Thallas V, Atkins RC, Osicka T, Jerums G, Cooper ME: Advanced glycation end products cause epithelial-myofibroblast transdifferentiation via the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). J Clin Invest 108: 1853–1863, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verrecchia F, Chu ML, Mauviel A: Identification of novel TGF-beta/Smad gene targets in dermal fibroblasts using a combined cDNA microarray/promoter transactivation approach. J Biol Chem 276: 17058–17062, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato M, Muragaki Y, Saika S, Roberts AB, Ooshima A: Targeted disruption of TGF-beta1/Smad3 signaling protects against renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis induced by unilateral ureteral obstruction. J Clin Invest 112: 1486–1494, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grotendorst GR, Okochi H, Hayashi N: A novel transforming growth factor beta response element controls the expression of the connective tissue growth factor gene. Cell Growth Differ 7: 469–480, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verrecchia F, Mauviel A: Control of connective tissue gene expression by TGF beta: Role of Smad proteins in fibrosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 4: 143–149, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen Y, Blom IE, Sa S, Goldschmeding R, Abraham DJ, Leask A: CTGF expression in mesangial cells: Involvement of SMADs, MAP kinase, and PKC. Kidney Int 62: 1149–1159, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lakos G, Takagawa S, Chen SJ, Ferreira AM, Han G, Masuda K, Wang XJ, DiPietro LA, Varga J: Targeted disruption of TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling modulates skin fibrosis in a mouse model of scleroderma. Am J Pathol 165: 203–217, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimoto M, Maezawa Y, Yokote K, Joh K, Kobayashi K, Kawamura H, Nishimura M, Roberts AB, Saito Y, Mori S: Mice lacking Smad3 are protected against streptozotocin-induced diabetic glomerulopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 305: 1002–1007, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang A, Ziyadeh FN, Lee EY, Pyagay PE, Sung SH, Sheardown SA, Laping NJ, Chen S: Interference with TGF-beta signaling by Smad3-knockout in mice limits diabetic glomerulosclerosis without affecting albuminuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1657–F1665, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monnier VM, Cerami A: Nonenzymatic browning in vivo: Possible process for aging of long-lived proteins. Science 211: 491–493, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li YM, Steffes M, Donnelly T, Liu C, Fuh H, Basgen J, Bucala R, Vlassara H: Prevention of cardiovascular and renal pathology of aging by the advanced glycation inhibitor aminoguanidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 3902–3907, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teillet L, Verbeke P, Gouraud S, Bakala H, Borot-Laloi C, Heudes D, Bruneval P, Corman B: Food restriction prevents advanced glycation end product accumulation and retards kidney aging in lean rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1488–1497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Makita Z, Radoff S, Rayfield EJ, Yang Z, Skolnik E, Delaney V, Friedman EA, Cerami A, Vlassara H: Advanced glycosylation end products in patients with diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 325: 836–842, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawano H, Kim S, Ohta K, Nakao T, Miyazaki H, Nakatani T, Iwao H: Differential contribution of three mitogen-activated protein kinases to PDGF-BB-induced mesangial cell proliferation and gene expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 584–592, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Izumi Y, Kim S, Namba M, Yasumoto H, Miyazaki H, Hoshiga M, Kaneda Y, Morishita R, Zhan Y, Iwao H: Gene transfer of dominant-negative mutants of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase prevents neointimal formation in balloon-injured rat artery. Circ Res 88: 1120–1126, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li JH, Zhu HJ, Huang XR, Lai KN, Johnson RJ, Lan HY: Smad7 inhibits fibrotic effect of TGF-Beta on renal tubular epithelial cells by blocking Smad2 activation. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1464–1472, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koka V, Wang W, Huang XR, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Truong LD, Lan HY: Advanced glycation end products activate a chymase-dependent angiotensin II-generating pathway in diabetic complications. Circulation 113: 1353–1360, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oshima M, Oshima H, Taketo MM: TGF-beta receptor type II deficiency results in defects of yolk sac hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis. Dev Biol 179: 297–302, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leveen P, Larsson J, Ehinger M, Cilio CM, Sundler M, Sjostrand LJ, Holmdahl R, Karlsson S: Induced disruption of the transforming growth factor beta type II receptor gene in mice causes a lethal inflammatory disorder that is transplantable. Blood 100: 560–568, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lan HY, Mu W, Tomita N, Huang XR, Li JH, Zhu HJ, Morishita R, Johnson RJ: Inhibition of renal fibrosis by gene transfer of inducible Smad7 using ultrasound-microbubble system in rat UUO model. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1535–1548, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Y, Zhu F, Yu X, Nie J, Huang F, Li X, Luo N, Lan HY, Wang Y: Treatment of established peritoneal fibrosis by gene transfer of Smad7 in a rat model of peritoneal dialysis. Am J Nephrol 30: 84–94, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore TC, Moore JE, Kaji Y, Frizzell N, Usui T, Poulaki V, Campbell IL, Stitt AW, Gardiner TA, Archer DB, Adamis AP: The role of advanced glycation end products in retinal microvascular leukostasis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44: 4457–4464, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serra R, Johnson M, Filvaroff EH, LaBorde J, Sheehan DM, Derynck R, Moses HL: Expression of a truncated, kinase-defective TGF-beta type II receptor in mouse skeletal tissue promotes terminal chondrocyte differentiation and osteoarthritis. J Cell Biol 139: 541–552, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W, Huang XR, Li AG, Liu F, Li JH, Truong LD, Wang XJ, Lan HY: Signaling mechanism of TGF-beta1 in prevention of renal inflammation: Role of Smad7. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1371–1383, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang XR, Chung AC, Zhou L, Wang XJ, Lan HY: Latent TGF-beta1 protects against crescentic glomerulonephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 233–242, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lan HY, Hutchinson P, Tesch GH, Mu W, Atkins RC: A novel method of microwave treatment for detection of cytoplasmic and nuclear antigens by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods 190: 1–10, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]